Abstract

The intestinal microecology is comprises intestinal microorganisms and other components constituting the entire ecosystem, presenting characteristics of stability and dynamic balance. Current research reveals intestinal microecological imbalances are related to various diseases. However, fundamental research and clinical applications have not been effectively integrated. Considering the importance and complexity of regulating the intestinal microecological balance, this study provides an overview of the high-risk factors affecting intestinal microecology and detection methods. Moreover, it proposes the definition of intestinal microecological imbalance and the definition, formulation, and outcomes of gut microecological prescription to facilitate its application in clinical practice, thus promoting clinical research on intestinal microecology and improving the quality of life of the population.

Keywords: intestinal microecology, risk, gut microecological prescription, definition, faecal microbiota transplantation

Introduction

Human gut microorganisms and their environment constitute the intestinal microecology, which includes various bacteria, fungi, archaea, viruses, and other intestinal microorganisms, host mucosa, nutrients, and metabolites. The gut microbiota occupies an important position in intestinal microecology, which is the largest and most complex ecosystem in the human body. The relationship between intestinal microecology and human health has been a popular research topic throughout history. Hippocrates, the founder of Western medicine, once proposed, “All diseases begin in the gut”.1 The characteristics of intestinal microecology include stability that gut microbiota oscillates around a stable ecological state without interference, resilience, and symbiosis with the host,2 of which stability is the most important. Intestinal microecological balance refers to the state of dynamic equilibrium between intestinal microecology (including gut microbiota, nutrients, and metabolites) and the host mucosal barrier. Intestinal microecological imbalance has been associated with various diseases, including colorectal tumors,3 diabetes,4–6 respiratory diseases,7 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),7 neurological diseases,8 renal diseases,9 and liver diseases.10 As the intestinal microecological system is complex and constantly changing, regulating the intestinal microecological balance is a challenge we are striving to solve. In 300 A.D., Ge Hong proposed a prescription to use ‘fermented faeces’ to treat terminal patients, which is the earliest record of using gut microecological prescription (GMP) to restore intestinal balance.11 Probiotics have also been used to treat various diseases.12 With the increase in cases of intestinal microecological imbalances, systematisation and regulation of intestinal microecological balance have become the focus of our research. As the number of cases of intestinal microecological imbalance increases, the systematic and scientific identification and evaluation of intestinal microecological imbalance and the adoption of a rational approach to correct intestinal microecological imbalance has become an urgent challenge, and the use of gut microecological prescription (GMP) is an important method. This study describes the development and application of GMP considering previous research and current investigations.

Methodology

This review aggregates and synthesises primary data generated and presented by various academic researchers investigating intestinal microecology, including the definitions, testing methods, processes, and interventions. The following search terms were employed in Google Scholar to identify pertinent studies for this analysis: the definition of dysbiosis, intestinal microbes, risk factors of intestinal microbes (genes, age, diet, region, pregnancy, delivery, feeding, stress, xenobiotics or drugs, infections, and diseases), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), assessment methods (intestinal gas testing, intestinal flora testing, intestinal barrier function assessment, and intestinal motility testing), gut microbes, and interventions (dietary prescription, antibiotics, probiotics/prebiotics/synbiotics/postbiotics, exercise prescription, faecal microbiota transplantation [FMT], prokinetic agents/digestive enzyme supplements/antidepressants, Traditional Chinese Medicine [TCM], and nutritional preparations). Only those studies that addressed issues related to intestinal microecology, whether beneficial or harmful, were included.

Development of GMP

Gut microbiota specialists should prescribe lifestyle interventions (such as exercise and diet), medications, nutrition, FMT, and other nutritional supplements to patients based on a comprehensive assessment of the intestinal microbiota. This assessment should include evaluating the risk factors and clinical symptoms and conducting intestinal microbiota function tests specific to the individual’s condition to restore the intestinal microecological balance.

The development of a GMP is divided into five parts: identification of risk factors, clinical presentation, assessment methods, diagnostic criteria, diagnostic ideas, and intervention methods.

Identification of Risk Factors

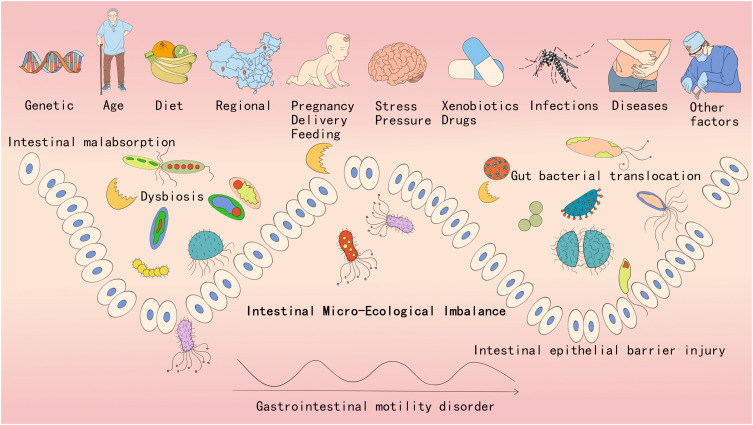

The first step in assessing intestinal microecological imbalance is identifying individuals who are at a high risk. Several factors influence intestinal microecological imbalance, as listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting intestinal microecology and classification of intestinal micro-ecological imbalances.

(1) Genetic: Although family members may share similar gut microbiota, each individual’s microbiota varies within specific bacterial lineages, with comparable levels of covariation between identical and fraternal adult twins. Nevertheless, a large amount of shared microbial genes exist among family members, including a broad, recognisable “core microbiome” at the gene level rather than at the level of the genealogy of the organisms.13 The Christensen family of bacteria is significantly influenced by genetic factors and is primarily associated with weight gain.14 This finding suggests that genetic factors selectively colonise certain flora, which play an important role in the intestinal microecological imbalance. Therefore, family history is a high-risk factor.

(2) Age: The gut microbiota varies with age. Generally, microbial diversity increases from childhood to adulthood and decreases with age (>70 years). Between the ages of 0 and 3 years, the microbiota in children is dominated by the mucinophilic Ackermannia, Bacteroidetes, and Veillonella.15 After the age of 3 years, the gut microbiota of children becomes comparable to that of adults, with three major microbial phyla, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinomycetes, becoming predominant.16 Changes in diet and the immune system also occur with advancing age. Older adults typically reveal a decrease in beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacteria, and an increase in harmful bacteria, such as Clostridioides difficile and Proteobacterium.17 Therefore, ages 0–3 years and >70 years are considered high-risk factors.

(3) Diet: Diet shapes the intestinal microecology and is a major factor that alters the diversity of the intestinal microbiome in both the short and long term. The typical “Western diet” is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, metabolic disease, and obesity. Diets rich in saturated fats can alter the gut microbiota by increasing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and trimethylamine-N-oxide levels and decreasing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).18 Thus, the consumption of high-fat, high-glycaemic, and low-fibre foods and excessive food additives and reduced intake of polyphenols, fermented foods, and probiotics are considered high-risk factors.

(4) Region: Studies have reported that differences in adult faecal microbiomes are related to geographical and cultural traditions. An analysis of populations in Venezuela, Malawi, and the United States revealed that the intestinal microbiome of populations in the United States differed significantly from that of the others.16 A British study of South Asian immigrants revealed that second-generation immigrants had a prevalence rate as high as that of indigenous Whites and Asian Jews, which was comparable to that of European or North American Jews in Israel, suggesting the role of environmental factors.19 Poor hygiene, environmental pollution, inadequate food intake, and unbalanced nutrition are considered high-risk factors.

(5) Pregnancy, delivery, and feeding: Early life may alter the intestinal microbes, and different microbial exposures and colonisations may affect allergies and atopic diseases.20 Current research suggests that the colonisation and formation of neonatal intestinal microbes may begin during in utero development.21 The overall profile of a child’s gut microbiota may be related to microbial alterations occurring before and during gestation.22 The type of delivery (vaginal or caesarean section) significantly affects the composition of the gut microbiota.23 The composition and development of the infant’s gut microbiota may be influenced by several prenatal factors, such as the mother’s diet, obesity status, smoking status, and use of antibiotics during pregnancy, which are typically cited as the major determinants of initial colonisation. Breast milk stimulates the development of the most balanced microbiome in infants, largely because of its uniquely high oligosaccharide content.24 Pre-pregnancy and gestational comorbidities, use of antibiotics or other medications during pregnancy, poor lifestyle, smoking or alcohol use during pregnancy, caesarean section, and lack of breastfeeding are considered high-risk factors.

(6) Stress or pressure: Stress has been revealed to affect the intestinal microbes. Moreover, in both animals and humans, stress causes a decrease in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and an increase in Clostridioides spp. and Escherichia coli due to an increase in catecholamines.25 Thus, stress is considered a high-risk factor.

(7) Xenobiotics or drugs: Xenobiotics (exogenous substances) are synthetic chemicals, including drugs, pesticides, natural food ingredients, food additives, and other contaminants, that can inhibit or promote bacterial growth, alter bacterial metabolism, and affect the enteroviralome and virulence of enteric bacteria, which in turn can metabolise and bioaccumulate xenobiotics, thereby altering their activity or toxicity.26 Intestinal microbes are the first to interact with orally administered drugs. The intestine is the second largest metabolic organ in the body after the liver. Drugs can alter the intestinal microenvironment, microbial metabolism or growth, and the composition and function of the microbial community.27 Hence, antibiotics, pesticides, food additives, and other pollutants are considered high-risk factors.

(8) Infections: Infections by intestinal pathogens are among the most direct causes of acute imbalances in intestinal microecology. Common pathogens include Clostridioides difficile, enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Foodborne pathogens are extremely lethal and often break through the defence barrier of the host’s gut microbiota.28 Opportunistic enteric pathogens may migrate to other infection sites owing to decreased body resistance or immune function. A direct example is spontaneous peritonitis in patients with cirrhosis. Both foodborne pathogenic infections and opportunistic pathogens are considered high-risk factors for intestinal microecological imbalances.

(9) Diseases: Several diseases can cause intestinal microecological imbalances and vice versa. Conditions such as IBD, surgical infections, or tumours can directly impair the intestinal barrier or affect intestinal motility. On the other hand, psychosomatic disorders or endocrine and rheumatological-immunological disorders indirectly influence intestinal microecology through the cerebral-intestinal axis, affecting the localised physicochemical properties, hormone levels, or dietary factors.29

(10) Other factors: Other risk factors may include lack of exercise30 and gastrointestinal surgery.31 Traditional Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) was approved to improve the disrupted gut microbiota linked with obesity,32 There are also other relevant risk factors that this review has not yet addressed, which deserve more investigation in the future.

Clinical Manifestations

Intestinal microecology is characterised by stability, resistance, and resilience.33 Healthy individuals experience intestinal microecological imbalances that return to normal after short-term fluctuations, and the imbalance arises only when they are unable to maintain stability or restore equilibrium. Intestinal microecological imbalances can be divided into acute, subacute, and chronic, depending on the time of onset. Acute imbalances generally occur within 4 weeks, and the aetiological factors include food, drugs, IBD, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), infections, and certain surgical disorders. Acute imbalances are generally characterised by fever, nausea, and vomiting, based on gastrointestinal symptoms, and these can result in water and electrolyte imbalance, hypoalimentation, and shock in severe cases. Subacute imbalances typically last for 5–23 weeks, whereas chronic imbalances last for ≥24 weeks. Subacute and chronic imbalance manifestations include diarrhoea, bloating, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, allergies, and leaky gut syndrome.34

The pathogenesis can be categorised based on decreased gut microbiota diversity, imbalance (decreased beneficial bacteria and increased harmful bacteria), impaired intestinal barrier function (leaky gut syndrome), gut bacterial translocation,35 gastrointestinal motility disorder, and absorption disorders (Figure 1).

Assessment Methods

The current methods for assessing intestinal microecological imbalances include intestinal gas testing, gut microbiota testing, intestinal barrier function assessment, and intestinal motility testing.

Intestinal Breath Test

The breath test is a safe, simple, and non-invasive method for detecting SIBO. It primarily measures the hydrogen concentration in the breath sample, and methane levels ≥10 parts per million (ppm) indicate methanogenic bacterial overgrowth. According to the 2017 North American expert consensus, an increase of 20 ppm at 90 min and 10 ppm at 2 h can confirm the diagnosis.36 The traditional test substrates used are glucose and lactulose. Currently, its results are affected by proton pump inhibitors, and it has low sensitivity and specificity. However, it can be used to detect gut microbiota and intestinal motility disorders. Gas-sensing capsule technology has been developed to measure the concentrations of various gases accurately in real time; however, its diagnostic value has not been investigated.37

Detection of Gut Microbiota

Owing to the differences in the microbiota of different parts of the intestinal tract, testing different parts of the tract, including small intestinal and faecal testing, is important. Although macrogenetic testing of the small intestine can be performed, it is not possible to determine the normal value limits as there is no standardised index for the normal value of the small intestinal bacterial flora test. The most commonly used intestinal bacterial test is faecal testing, which includes the methods described below.

Direct Smear

Currently, this method is the most widely used and is easy to perform. It mainly uses a microscope to observe gram-stained faecal smears, including the total number of bacteria, proportion of cocci and bacilli, ratio of gram-positive bacteria to gram-negative bacteria, and presence or absence of special infections, including yeast hyphae and Clostridioides difficile.

Faecal Bacterial Culture

This method involves inoculating fresh faeces directly onto different culture media, conducting strain identification after incubation, and quantifying the gut microbiota using fixed faeces. However, the bacterial cultures used in clinics are mainly restricted to pathogenic bacteria, and most bacteria cannot be cultivated in ordinary culture media. Moreover, it takes a long time, and the commonly used index is the Bifidobacteria/Enterobacteriaceae (B/E) value,38 where B/E >1 indicates normal composition of gut microbiota, and B/E <1 is considered abnormal. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of this assessment index are poor, and this index provides a relatively approximate assessment. Novel methods, such as culturomics, can be used to identify and isolate most bacteria; however, they are still far from being clinically applicable.

16s Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing and Metabolite Testing of Gut Microbiota

Current clinically applicable metagenomic methods of assessing gut microbiota include 16s ribosomal RNA (rRNA), high-throughput sequencing, and other methods. Among these, 16s rRNA has been gradually introduced in clinical settings because of its advantages of measuring more bacterial species and high sensitivity and specificity; however, they still need to be optimised in terms of time efficiency, normal range for healthy individuals, and cost effectiveness. It can detect indicators such as gut microbiota diversity, pathogen species, intestinal barrier, harmful bacteria, beneficial bacteria, colonisation resistance, and antimicrobial resistance. Intestinal metabolite testing can also indirectly reflect overall intestinal microecology.

Assessment of Intestinal Permeability

Research shows that gut microbiota affects intestinal permeability through various mechanisms. For example, the byproducts of probiotics, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), can strengthen the tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells, which helps lower intestinal permeability. However, when the microbiome is out of balance, the growth of bad bacteria can make intestinal inflammation worse, which can damage the intestinal barrier and lead to leaky gut syndrome.39 Therefore, testing for intestinal permeability is key to understanding gut microbiome imbalance.

Lactulose/Mannitol Test

This is a simple, non-invasive test to assess intestinal permeability. In this test, the patient drinks a solution containing lactulose and mannitol, and urine samples are collected over a 6 h period. Lactulose and mannitol levels are measured to determine the presence and extent of intestinal leakage. The test investigates the lactulose concentration, mannitol concentration, total urine volume, and mannitol/lactulose ratio. Values <0.03% are considered normal, and elevated ratios indicate excessive intestinal permeability. Different periods, geographic locations, diets, renal injury, and allergies can affect the results. Nevertheless, this test remains a cost-effective screening test for intestinal permeability.40 Different sugar solutions and collection times can be used to measure the intestinal permeability at different sites. Currently, ‘polysaccharide tests’, involving sucrose, lactulose, sucralose, erythritol, and rhamnose, can be used to assess the permeability of the human gastroduodenum, small intestine, and colon.41 Moreover, the urinary fraction of saccharide excretion can be measured following oral administration of a molecular probe.42 As it is not absorbed, it serves as an indirect measure of intestinal permeability.

Endoscopy

The leakage of fluorescein after intravenous injection was measured using a confocal microscope equipped with a 488 nm laser. The parameters observed included the percentage of gap enhancement between the epithelial cells, leakage of fluorescein into the intestinal lumen, and shedding of cells.43 However, owing to its invasiveness and high cost, it is not available for wide-scale application in clinical practice. In contrast, the endoscopic mucosal impedance test measures the electrical resistance of the mucosal tissue directly through an endoscope, thus determining the permeability of the intestinal mucosa.44

Serum Markers

The search for suitable serum markers has become an important research topic owing to the complexity and cost-effectiveness of other assays. Currently, the two types of measured markers include molecular markers that enter the bloodstream from the intestinal lumen owing to damage to the intestinal barrier, such as endotoxins (LPS), and endotoxin-binding proteins (LPS-binding protein).45 The first step is to screen for increased levels of proteins in the intestinal barrier, such as intestinal fatty acid-binding proteins46 or tight junction molecules (zonulin). Currently, zonulin is the most widely used protein for determining intestinal barrier permeability. Zonulin proteins are used to treat celiac disease, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, IBD, obesity, and others diseases.47

Gastrointestinal Motility Test

The relationship between IMEI and gastrointestinal motility is getting increasing attention. Research shows that gut microbiota is really important in digestion and nutrient absorption, but also affects how the gut moves through its metabolic products and signaling. IMEI can cause a bunch of gastrointestinal diseases, including constipation, diarrhea, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), that are closely linked to motility issues.One study found that changes in the gut microbiome can impact how the intestines move and sense things, leading to functional dyspepsia and intestinal motility disorders.48 Furthermore, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) made by gut microbes are seen as key players in controlling how the intestines move, since SCFAs help the intestinal smooth muscle contract and boost overall gut movement.49 The gastrointestinal motility test mainly examines the motility of the stomach, intestine, and anus; oesophageal motility tests are not included here. The different test methods are described below.

Gastric Motility Test

Gastric scintigraphy is the gold standard method for examining gastric emptying rates. This method generally involves the ingestion of a test radioisotope-labelled meal, typically 99 mTc. At 0, 1, 2, and 4 h after ingestion, photographs are captured in the anterior and posterior positions using a gamma camera to visualise the distribution of the labelled food within the stomach. Normal rate of gastric emptying is characterised by <90% gastric retention at 1 h, <60% retention at 2 h, and <10% retention at 4 h. However, if the rate of gastric retention is >10% at 4 h, delayed solid emptying is diagnosed.50,51 Other methods utilised include gastrointestinal manometry techniques,36 C13 breath test,52 wireless motion capsule,53 and electrogastrography.50

Gastric Tolerance Test

Gastric tolerance tests include electron-constant pressure testing,54 ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, single-photon emission computed tomography,55 and liquid nutrient-meal testing.56 The electron constant pressure test is an invasive test with several drawbacks that limit its use in clinical settings. The liquid nutritional meal test is a relatively simple and non-invasive measure of gastric tolerance; however, its fit is relatively demanding. Currently, imaging tests, such as ultrasonography, are mainly used for scientific research but not used on a wide clinical scale yet.

Bowel Mobility Test

Currently, bowel mobility tests are performed using gastric sinus duodenal manometry,57 flash shrinkage imaging,51 wireless motion capsule,53 hydrogen breath test,36 and colonic transport test. The colon transport test is widely used and is mainly based on the use of impermeable radiographic markers for patients to swallow; the diagnostic criterion is the inability to expel 80% of the markers within 72 h. However, the test is easily affected by medication, food, and other factors and can be repeated if necessary.58 Wireless motion capsules are more promising because they react to colonic transport and collect information on various parameters, including gastric, small intestinal, and colonic transport (function), intraluminal pressure (motility), and pH (metabolites of bacterial fermentation in the colon).59,60

Rectal/Anal Function Test

The main measurements include the function of the rectal and anal sphincters and the pelvic floor musculature. The test methods included anal ultrasonography, anal manometry, rectal function tests, balloon evacuation tests, and defecography test.61 The defecography test simulates the structure and function of the pelvic floor during defecation.62

Absorption and Secretion Function Test

This test mainly focuses on the absorption and secretion functions of the pancreas, gallbladder, and intestines, which are components of the normal intestinal microecological environment. The pancreatic exocrine function tests include both direct and indirect tests that are sensitive but invasive, and their clinical application is limited. Indirect tests include the faecal elastase-1 test, C13-MTG-BT breath test,63 and others. Trypticin-stimulated magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatic duct imaging involves a semi-quantitative test of pancreatic exocrine function.64 Assessing haematological electrolytes, liver and renal function, blood counts, vitamins, folic acid, and iron can assist in diagnosing small intestinal malabsorption dysfunction. The faecal test, a 72-h faecal assessment of fat excretion, is the most sensitive for investigating fat malabsorption syndrome.65

Diagnostic Criteria

Currently, there are no clear diagnostic criteria for intestinal microecological imbalance. According to the definition of diarrhoea and the intestinal microbiota recovery rhythm after using antibiotics,66–68 acute intestinal microecological imbalance lasts for ≤4 weeks, subacute intestinal microecological imbalance for 5–23 weeks, and chronic intestinal microecological imbalance for ≥24 weeks. The diagnostic criteria are mainly based on risk factors, gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhoea, abdominal distension, pain, discomfort, Leaky Gut Syndrome), laboratory or examination evidence. So far, there’s no objective testing method to diagnose imbalance in gut microbiota, We have just provided a framework for diagnosing gut microbial imbalance. The more positive the risk factors or test results, the more reliable the diagnosis. The difference between this definition and dysbiosis is that the intestinal microecological imbalance emphasises an imbalance of the overall intestinal ecosystem rather than a purely microbial imbalance.

Diagnostic Approach

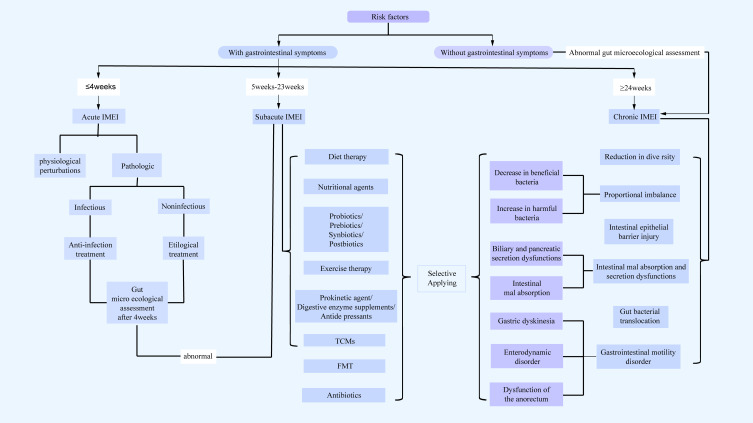

Given the complexity of intestinal microecology, intestinal microecological imbalance diagnosis and GMP should follow the structure depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The diagnostic ideas and intervention process of GMP.

Abbreviations: IMEI, intestinal micro-ecological imbalance; FMT, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation; TCMs, Traditional Chinese Medicines.

Methods of Intervention

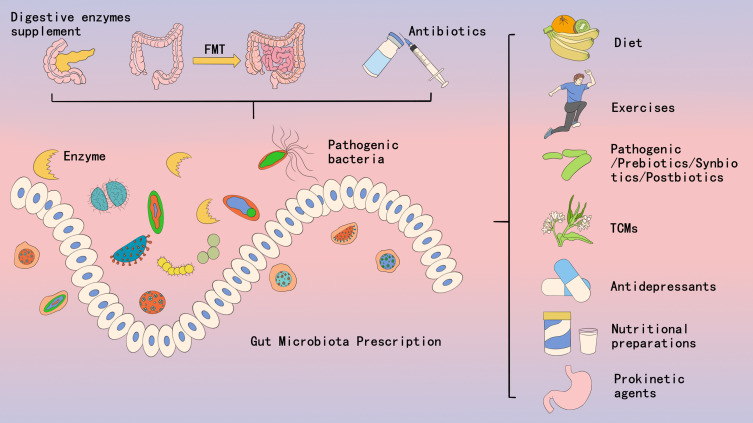

The main approaches currently used to treat intestinal microecological imbalance include dietary prescriptions, antibiotics, probiotics/prebiotics/synbiotics/postbiotics, exercise prescriptions, FMT, prokinetics/digestive enzyme supplements, herbal medicines (TCM), and nutritional agents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The intervention methods of GMP.

Abbreviations: FMT, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation; TCMs, Traditional Chinese Medicines.

Dietary Prescription

Dietary prescriptions should be individualised according to patient symptoms and intestinal microecological balance test results. A low-fat, high-fibre diet can positively alter the intestinal microbiota by reducing harmful bacteria, such as Acanthamoeba, and increasing the beneficial bacteria, such as Prevotella and Bacteroides.69 The Mediterranean diet, which is predominantly plant-based, high in fibre and omega-3 fatty acids, and low in animal proteins and saturated fatty acids, has been reported to increase the diversity of the gut microbiota compared to the Western diet.70 The Mediterranean diet positively affects health by increasing the levels of SCFAs and anti-inflammatory components, thereby reducing the incidence of chronic diseases.71,72 FODMAP diet is an acronym for Fermentable Oligosaccharides (fructans and oligogalactans or galacto-oligosaccharides), Disaccharides (lactulose), Monosaccharides (excess fructose), and Polyols (sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and maltitol). FODMAPs are common in our daily diets, which can increase intestinal water content,73 produce large amounts of gas,74 and produce excess SCFAs.75 Reduced intake of FODMAP diets can provide some degree of symptomatic relief to patients with IBS.76,77 Intermittent fasting regimens can directly influence the gut microbiome by amplifying diurnal fluctuations in bacterial abundance and metabolic activity. This process subsequently leads to fluctuations in the levels of microbial constituents (LPS) and SCFAs, which are metabolites that act as signalling molecules for the host’s peripheral and central clocks. These metabolites are important for the treatment and prevention of disorders associated with circadian disruption (obesity and metabolic syndrome).78 Similar dietary regimens include alternate-day fasting, time-restricted fasting, and intermittent energy restriction; all these approaches have a similar effect.79 The ketogenic diet was initially used to treat refractory childhood epilepsy and is characterised by reduced intake of carbohydrates (5–10% of the total caloric intake), sufficient to increase ketone production. The gut microbiota’s response to the ketogenic diet seemed to improve the efficacy of interventions in children with epilepsy.80 Currently, microbe-targeted diets are gaining attention, and there is a consensus that foods containing probiotics or metabolites modulate the gut microbiota and provide health benefits.81,82 Although higher-level clinical evidence is lacking, dietary regimens based on intestinal microbial targeting are gradually becoming mainstream.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are a two-edged sword. They typically eradicate Bacteroides, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, which are responsible for important gut microbiota functions. Antibiotic therapy in adults typically causes an increase in the relative abundance of parthenogenetic anaerobes, such as Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus, and Clostridioides, as well as Streptococcus.68,83–85 Different antibiotics are selected depending on the intestinal microbial pathogens. Clostridioides difficile infections (CDI) require discontinuation of antibiotics and treatment with vancomycin.86 Both ciprofloxacin and azithromycin decrease the diversity of the gut microbiota.87–89 Ciprofloxacin also decreases the abundance of Bifidobacteria and Rumenococci.90 Antibiotics can have both favourable and unfavourable effects on intestinal microecology, and selective antibiotics must be administered based on the outcome of the gut microbiota. The tendency of antibiotics to bioaccumulate in the gastrointestinal tract varies depending on their chemical composition, formulation, and administration route.91 The use of oral β-lactamase,92 DAV132,93 prebiotics,94,95 gut microbiota transplantation,96,97 and probiotics98 can minimise the effects of antibiotics on intestinal microecological imbalances, thereby restoring intestinal microecological balance as quickly as possible. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics can target the removal of certain pathogenic bacteria with less impact on the overall intestinal microbial balance. Future research should focus on the more targeted use of antibiotics and reducing their influence on intestinal microecology.

Probiotics/Prebiotics/Synbiotics/Postbiotics

Probiotics can contribute to the balance of the host’s gut microbiota99 or improve the properties of the commensal microbiota.100 The most widely used probiotics include Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Saccharomyces spp. Some bacteria, such as Roseburia, Akkermansia muciniphila, Propionibacterium, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, reveal promise as probiotics. They have several mechanisms of action, including modulation of immune function, production of organic acids and antimicrobial compounds, interactions with the commensal microbiota, host interactions, improvement of intestinal barrier integrity, and enzyme formation.101 Prebiotics are defined as “substrates that are selectively used by host microorganisms for beneficial health effects”. Prebiotics cannot be simply considered as mere growth stimulators for Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium; they can have positive effects on the physiological and metabolic systems throughout the body.102 The elucidated actions of prebiotics include defence against colonisation by pathogens,103 immunomodulation,104 increased mineral absorption,105 improved intestinal function,106 regulation of metabolism,107 and effects on appetite.108 Synbiotics are a combination of prebiotics and probiotics. Postbiotics are preparations of inanimate microorganisms or other components that are beneficial to the health of the host and are not purified microbial metabolites or vaccines.109 Postbiotics can enhance the function of the intestinal epithelial barrier,110 regulate the immune response111 and systemic metabolic capacity,112 and transmit neural signals.113 The use of probiotics or prebiotics for intestinal microecological imbalances is currently recognised; however, the specific types and dosages for different imbalances remain to be investigated.

Exercise Prescription

Recent studies have reported that exercise can alter the abundance and function of the intestinal bacteria.114 An early study on gut microbiota revealed that professional rugby players have a significantly higher abundance and diversity of gut microbiota and metabolic function than the general population of the same age and body mass index.115 Another study on people with Type 2 diabetes reported that exercise intensity plays a role in shaping the gut microbiota. Eight weeks of aerobic training resulted in a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila, butyric acid-producing Lachnospira eligens, Enterococcus, and Clostridioides than high-intensity interval training.116 The ability of exercise to increase the intestinal microbiome diversity (Shannon index) suggests that regular exercise may modulate the microbial composition and ameliorate intestinal microecological imbalances.117 Coordinated interventions with multiple types of exercise have a significant effect on the diversity of the gut microbiota.118 Thus, multiple forms of exercise interventions possibly increase diversity than a single type of exercise. Exercise increases the number of beneficial bacteria and decreases the number of harmful bacteria in adults.119 The relative abundances of Roseburia hominis and Akkermansia muciniphila were significantly higher in active adults than in sedentary individuals.120 Moreover, both exert beneficial effects on host gastrointestinal health, lipid metabolism, and the immune system owing to their production of butyric acid.

FMT

FMT involves the transfer of minimally processed faeces from a healthy donor into the intestinal tract of a recipient to treat diseases associated with intestinal microbiota imbalance. FMT has been successfully used in severe and recurrent CDI with efficacy rates approaching 90%.121 Owing to its excellent performance in the treatment of CDI, FMT has been used to treat various chronic disorders associated with intestinal microbiota imbalance, including IBD,122 IBS,123 metabolic syndrome,124 and neurologic psychiatric disorders.125 Although the use of FMT in treating diseases other than CDI is controversial, it remains an important approach for improving intestinal microecological imbalance in the future. The main challenges in applying FMT in other diseases include inconsistent transplantation results, donor characteristics,126 recipient characteristics,127 and transplantation specifications.128 As several chronic diseases are treated over a long period, the use of novel flora transplantation methods, such as capsules, may be important for large-scale clinical applications in the future.129 However, FMT may be a double-edged sword, as it can remove or colonise certain harmful microorganisms during transplantation.130,131 Future studies should investigate the long-term efficacy and adverse effects of FMT.

Prokinetic Agents/Digestive Enzyme Supplements/Antidepressants

Gastrointestinal motility is essential for the smooth passage of food through the intestine.132 In addition to host-specific genetic predispositions to normal peristalsis, diet and the microbiota are important regulators of gastrointestinal motility.133–135 Dysregulation of these factors leads to impaired peristalsis, causing several disorders, such as IBS with hypoplasia of transmission.136,137 The most notable intrinsic factors preventing SIBO138 are gastric and bile acid secretion, peristalsis, normal intestinal defence mechanisms, mucin production, intestinal antimicrobial peptides, and the prevention of retrograde translocation of bacteria from the lower to the upper intestines via the ileocecal valve.139,140 Extrinsic factors include nutrient intake and diet, bacterial and viral infections, medications (prokinetic drugs) that alter gastrointestinal motility, and agents that modulate gut microbiota, such as prebiotics, probiotics, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, and antibiotics.141,142 Prokinetic agents can improve dyskinesia in the gastrointestinal tract.143 Patients with chronic pancreatitis suffer from digestive enzyme deficiency, which leads to an imbalance in the gut microbiota.144 Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy can improve digestive symptoms in chronic pancreatitis.145 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are particularly effective against gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococci and Enterococcus, as well as against certain harmful bacteria, such as Citrobacter, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Clostridioides perfringens, and Clostridioides difficile.146,147

TCM

TCM formulations are generally processed by the gut microbiota. The interaction between the gut microbiota and TCM formulations mainly occurs through three different pathways. One pathway is where the gut microbiota “digests” the herbal medicines into absorbable active small molecules, which enter the body and induce physiological changes. Second, the TCM formulations regulate and change the composition of the gut microbiota and its secretion, thereby achieving the purpose of regulating the intestinal microecological balance.148 Third, intestinal microbiota mediates the interactions (synergistic and antagonistic) between various chemicals in TCM formulations.149 The isoquinoline alkaloid berberine extracted from the Chinese medicine Huanglian has been reported to have specific antimicrobial activity and can improve intestinal imbalance in mice with colon carcinoma, which can result in tumour suppression.150 Carboxymethylated Poria polysaccharide is modified from the structure of polysaccharides isolated from Poria cocos and exhibits specific antimicrobial activity. Recent studies have shown that it can increase the proportion of anabolic, lactic acid-producing, butyric acid-producing, and acetic acid-producing bacteria, thus restoring the diversity of the gut microbiota in intestinal microecological imbalances.151 Ephedra sinica and Rehmannia glutinosa modulate intestinal microecological imbalances in patients with obesity.152 Bacillus Calmette-Guérin has been reported to modulate the species and composition of gut microbiota, increase the levels of beneficial bacteria, and elevate neurotransmitter levels in the brain and colonic faeces, thereby improving insomnia.153 Thus, herbal medicines play an important role in correcting intestinal microecological imbalances.

Nutritional Preparations

Some nutritional agents can restore intestinal microecological balance. Malnutrition has a significant impact on the gut microbiota of older individuals, with changes occurring primarily in Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. Enteral nutritional suspensions (triple-protein formula [TPF] for diabetes management) prevent further decline in nutritional status and facilitate the restoration of the gut microbiota of older adults.154 For some patients with malnutrition, the use of TPF may improve the intestinal barrier and restore the intestinal microecological balance. Glutamine may also improve the intestinal microecological imbalance in patients with obesity155 and increase the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Proteobacteria in animal models of constipation.156 Furthermore, it prevents bacterial translocation and increases the intestinal permeability.157 When ingested in large quantities or delivered to the colon, some vitamins may increase microbial diversity by increasing the abundance of presumed commensal bacteria (vitamins A, B2, D, E, and β-carotene), increase or maintain microbial diversity (vitamins A, B2, B3, C, and K) and abundance (vitamin D), increase the production of SCFAs (vitamin C), or increase the abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria (vitamins B2 and E) to modulate the intestinal microbiota beneficially. Other vitamins, such as vitamins A and D, may modulate intestinal immune responses or barrier functions, thus indirectly affecting gastrointestinal health or microbiota.158 Other nutrient agents that may have a modulatory effect on the intestinal microecological balance are still being discovered, and extensive clinical studies are needed to confirm this.

Potential GMP Suggestions

We have summarised various GMP interventions according to recent systematic reviews (Table 1). Despite the complexity of intestinal microecology and heterogeneity of randomised controlled studies, we can prescribe GMPs based on the currently available evidence that helps to improve intestinal microecological balance, as summarised below. (1) Different dietary approaches can have different effects on intestinal microecological imbalance. Among them, the Mediterranean diet can improve the diversity of gut microbiota in most of the population. (2) Engaging in moderate to high-intensity exercise for 30 to 90 minutes at least three times a week, or for a total of 150 to 270 minutes weekly over at least 8 weeks, can likely change the intestinal microbiota. (3) Probiotics are the most researched and play a role in several diseases; however, the species, dosage, duration, and effects remain to be investigated. (4) TCM formulations play a role in some of the intestinal microecological imbalances. (5) FMT may be an effective solution for intestinal microecological imbalance, particularly in recurrent CDI. However, there is a shortage of high-quality studies on its safety and long-term effectiveness in other conditions. (6) High-quality systematic reviews on the effects of prokinetic agents/digestive enzyme supplements on IMEI are lacking. However, the interaction between antidepressants and intestinal microecology has been recognised. (7) Vitamins and certain nutritional preparations could regulate intestinal microecology; however, high-quality clinical studies are warranted to prove it. (8) Certain narrow-spectrum antibiotics can eliminate bacteria from certain specific infections, for instance, vancomycin for CDI, and the correction of intestinal microecological imbalance using other antibiotics should be investigated.

Table 1.

Summary of Various Intestinal Microecological Interventions in the Literature

| Intervention | Publication Year | Specific Intervention Strategies | Type of Article | Author | Number of Studies | Diseases/Outcome | Quality of Evidence | Intervention Groups | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | 2024 | Dietary intervention | Systematic review | Linli Cai159 | 36 meta-analyses | Diabetic nephropathy | Moderate to low | Adult | Probiotics, vitamin D, soy isoflavones, coenzyme Q10, polyphenols, antioxidant vitamins, or salt-restricted diets may improve outcomes in diabetic nephropathy patients. |

| 2023 | Honey, glutamine, and propolis | Systematic review | Reza Amiri Khosroshahi160 | 26 meta-analyses | Cancer therapy-induced oral mucositis | Moderate | Adult | Honey, glutamine, and propolis can significantly reduce the incidence of severe oral mucositis. | |

| 2024 | Mediterranean diet | Network meta-analysis | Ioannis Doundoulakis161 | 17 RCTs | Cardiovascular disease | Unknown | Adult | Mediterranean diet may play a protective role against cardiovascular disease and death in primary and secondary prevention. | |

| 2024 | Mediterranean diet | Systematic review | Armin Khavandegar162 | 17 observational and 20 interventional studies | Gut microbiota composition | Unknown | Adult | Adherence to the Mediterranean diet improves gut microbiota diversity and composition, leading to significant clinical benefits. | |

| 2024 | Low FODMAP diet | Systematic review | Sandra Jent163 | 19 real-world studies | Irritable bowel syndrome | Unknown | Adult | Low FODMAP diet improves outcomes compared to a control diet (efficacy studies) or baseline data (real-world studies). | |

| 2024 | Intermittent fasting | Network meta-analysis | Mohamed T Abuelazm164 | 8 RCTs | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease | Unknown | Adult | Alternate-day fasting improved anthropometric measures, including lean body mass, waist circumference, fat mass, and weight loss. | |

| 2023 | Intermittent Fasting | Systematic review | Theodoro Pérez-Gerdel165 | 9 studies (all with longitudinal design) | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes increased, with 16 genera varying due to intermittent fasting, linked to clinical predictors like weight change and metabolic variables, boosting gut microbiota diversity. | |

| 2023 | Ketogenic diet | Systematic review | Mahdi Mazandarani166 | 9 clinical trials and cohorts | Gut microbiota, metabolites | Unknown | Neurological patients | A ketogenic diet reduces disease severity and recurrence, alters gut bacteria by increasing Proteobacteria and decreasing Firmicutes, and changes metabolite levels. | |

| Exercise | 2024 | Exercise | Systematic review | Leizi Min119 | 25 controlled trials | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Exercise can improve gut microbiota in adults, with a significant increase in the Shannon index; however, responses vary by sex and age, indicating a need for further research. |

| 2023 | Exercise | Systematic review | ML Lavilla-Lerma167 | 13 RCTs | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Modulating gut microbiota depends on exercise type, intensity, and duration, affecting specific microbial populations more than richness and diversity. | |

| 2023 | Exercise | Systematic review | Alexander N Boytar168 | 28 trials (randomised controlled trials, cohort studies and case-control studies) | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Regular moderate to high-intensity exercise for 30–90 min at least 3 times a week can change gut microbiota in 8 weeks, benefiting both clinical and healthy individuals. | |

| Probiotics/prebiotics/synbiotics/postbiotics | 2024 | Probiotics supplementation | Systematic review | Zihan Yang169 | 534 RCTs | Helicobacter pylori infection | High | Adult | Probiotic supplementation improved eradication rates (risk ratio 1.10) and reduced side effects (risk ratio 0.54) compared to standard therapy. |

| 2024 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Minjuan Han170 | 13 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Ventilator-associated pneumonia | Low | Adult | Probiotics may be associated with a reduced incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. | |

| 2024 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Yunxin Zhang171 | 7 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Functional constipation | Low | Children | Probiotics may be beneficial in improving functional constipation in children. | |

| 2023 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Reza Amiri Khosroshahi172 | 13 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-related diarrhoea | Low | Adult | Probiotics use can reduce the incidence of diarrhoea induced by chemotherapy and radiotherapy in cancer patients. | |

| 2023 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Qingrui Yang173 | 20 systematic reviews | Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea | Moderate to low | Children | Probiotics prevent and treat antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in children, possibly showing a dose-response effect. | |

| 2023 | Probiotics/prebiotics/and synbiotics | Systematic review | Pooneh Angoorani174 | 8 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Polycystic ovarian syndrome | High to low | Adult | Probiotic supplementation may benefit some polycystic ovarian syndrome parameters like BMI, glucose, and lipids, but synbiotics are less effective. | |

| 2022 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Haissan Iftikhar175 | 3 systematic reviews | Allergic rhinitis | Moderate to low | Adult | Probiotics are useful in treating allergic rhinitis. | |

| 2022 | Prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics/FMT | Systematic review | Nathalie Michels176 | 57 meta-analyses | Metabolic disorders | Moderate to low | Adult | Meta-evidence was the highest for probiotics and lowest for FMT. | |

| 2021 | Probiotics | Systematic review | E Earp177 | 3 systematic reviews | Atopic eczema | Low | Pregnancy of infancy | Probiotics during pregnancy or infancy were analyzed, but low-quality evidence indicates limited benefits of combined probiotics. | |

| 2019 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Mikołaj Kamiński178 | 8 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Chronic idiopathic constipation | Low | Adult | Probiotics are recommended, but their effectiveness for adult constipation is unclear. | |

| 2020 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Tao Xiong179 | 98 meta-analyses of RCTs | Necrotising enterocolitis | Very low to moderate | Preterm Infants | Decreased risk of necrotising enterocolitis is observed with probiotics. | |

| 2019 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Rachel Perry180 | 16 systematic reviews | Infantile colic | Low | Infant | A particular focus on probiotics in non-breastfed infants is pertinent. | |

| 2019 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Ibrahim Nadeem181 | 7 systematic reviews | Depression | Unknown | Adult | Probiotics seem to produce a significant therapeutic effect in individuals with pre-existing depressive symptoms. | |

| 2018 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Rebecca A Abbott182 | 55 RCTs | Recurrent abdominal pain | Unknown | Children | He evidence for treatment decisions is poor; probiotics, cognitive behavioural therapy, and hypnotherapy may aid in managing children’s recurrent abdominal pain. | |

| 2016 | Probiotics | Systematic review | Jinpei Dong183 | 36 systematic reviews/meta-analyses | Inflammatory bowel disease and pouchitis | Moderate to low | Adult | Probiotics may help ulcerative colitis but not Crohn disease remission; VSL#3 may aid pouchitis. | |

| 2016 | Probiotics | Systematic review | YA McKenzie184 | 9 systematic reviews and 35 RCTs | Irritable bowel syndrome | Unknown | Adult | Symptom outcomes for dose-specific probiotics varied, making specific recommendations for irritable bowel syndrome management in adults impossible now. | |

| 2024 | Probiotics/prebiotics | Systematic review | Md. Nannur Rahman185 | 29 RCTs | Colonisation resistance in the gut | Moderate | Human and animal | Probiotics and prebiotics may reduce pathogens by modulating gut diversity, but more clinical data on specific strains is needed to confirm this. | |

| TCM | 2022 | Herbal medicine | Systematic review | Hyejin Jun186 | 18 systematic reviews | Irritable bowel syndrome | Low | Adult | Herbal medicines can be considered as an effective and safe treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. |

| 2019 | Fennel extract | Systematic review | Rachel Perry180 | 16 systematic reviews | Infantile colic | Low | Infant | Fennel extract shows potential in alleviating colic symptoms. | |

| FMT | 2024 | Chemical drugs/FMT/Probiotics/Dietary fibre/Acupuncture | Network meta-analysis | Shufa Tan187 | 45 RCTs | Chronic functional constipation | Unknown | Adult | FMT shows the best clinical efficacy and stool form scores, along with improved patient quality of life. |

| 2024 | Probiotics/Prebiotics/Synbiotics/FMT | Systematic review | Mahmoud Yousef188 | 27 RCTs | COVID-19-induced gut dysbiosis | Unknown | Adult | The review enhances our understanding of biotics’ therapeutic potential for COVID-19-related intestinal issues and multi-organ complications. | |

| 2024 | FMT | Systematic review | Yan Yang189 | 4 RCTs | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Unknown | Adult | FMT treatment in Type 2 diabetes reduces postprandial glucose, triglycerides, insulin resistance, cholesterol, ALT, and diastolic blood pressure, particularly with combined therapy, while also reshaping gut microbiota. | |

| 2023 | FMT | Systematic review | Azin Pakmehr190 | 11 clinical trials | Cardiometabolic risk | Unknown | Adult | While some articles noted FMT’s benefits on metabolic parameters, we found no significant changes. | |

| 2024 | FMT | Meta-analysis | Shafquat Zaman191 | 17 observational studies and 2 RCTs | Chronic refractory pouchitis | Low | Adult | Current evidence from low-quality studies suggests a variable clinical response and remission rate. | |

| 2023 | FMT | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Serena Porcari192 | 15 clinical trials | rCDI | Unknown | Adult | FMT showed high cure rates for rCDI in inflammatory bowel disease patients, with overall FMT outperforming single FMT, similar to non-inflammatory bowel disease data, supporting FMT’s use for rCDI treatment in these patients. | |

| 2023 | FMT | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Parnian Jamshidi193 | 7 RCTs | Irritable bowel syndrome | Unknown | Adult | Lower gastrointestinal administration of multiple-donor FMT significantly improves patient complaints over autologous FMT as a placebo. | |

| 2023 | FMT | Systematic Review and meta-analysis | Jing Feng194 | 13 RCTs | Ulcerative colitis | Unknown | Adult | FMT shows potential for inducing remission in ulcerative colitis, but achieving and maintaining endoscopic remission is challenging. | |

| 2023 | FMT | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Li Zecheng195 | 10 RCTs | Obesity metabolism | Unknown | Adult | FMT benefits obese patients with high blood pressure, glucose issues, and elevated lipids; studying metabolic factors in these patients will be our future focus. | |

| Prokinetic agents/Digestive enzyme supplements/Antidepressants | 2023 | Psychotropic medications | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Amedeo Minichino196 | 19 longitudinal and cross-sectional studies | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Psychotropic medications alter gut microbiota, which may affect their efficacy and tolerability. |

| Nutritional preparations | 2022 | Antioxidants, probiotics, prebiotics, camel milk, and vitamin D | Systematic review | Cecilia N Amadi197 | 21 clinical trails | Autism | Unknown | Children | Dietary supplements like antioxidants, probiotics, prebiotics, vitamin D, and camel milk may reduce inflammation and improve autism symptoms by targeting the cerebral-intestinal axis safely. |

| 2023 | Vitamin B12 | Systematic review | Heather M Guetterman198 | 22 studies (3 in vitro, 8 animal, 11 human observational studies) | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Vitro, animal, human | Few prospective observational studies but no RCTs have been conducted to examine the effects of vitamin B-12 on the human gut microbiota. | |

| 2021 | Vitamin D | Systematic review | Federica Bellerba199 | 14 interventional and 11 observational studies | Gut microbiota | Unknown | Adult | Vitamin D supplementation changed microbiome composition, notably Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes, correlating with serum vitamin D levels, reducing Veillonellaceae and Oscillospiraceae families. | |

| Antibiotics | 2021 | Oral fidaxomycin | Systematic review | Adelina Mihaescu200 | 2 RCTs/2 Non-RCTs | CDI | Unknown | Adult | Treatment with oral fidaxomycin is more effective than oral vancomycin for the initial episode of CDI in patients with chronic kidney disease. |

| 2021 | Azithromycin + metronidazole | Systematic review | Charlotte M Verburgt201 | 2 RCTs | Crohn disease | Unknown | Children | In mild-to-moderate Crohn disease, azithromycin + metronidazole (n = 35) showed no significant response difference from metronidazole alone (n = 38) (p = 0.07), but was more effective for remission induction (p = 0.025). |

Abbreviations: FODMAP, Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine; FMT, Faecal microbiota transplantation; RCTs, Randomised controlled trials; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; rCDI, Recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection; PCDI, pediatric Crohn's disease activity index.

Discussion

Although we have proposed the concept of GMP, it is still an evolving concept and its application in the future has certain challenges. These challenges include but are not limited to the issues described here. The first is cost-effectiveness. For instance, although FMT has been used in diseases such as recurrent CDI, it remains relatively expensive owing to the high standards set for qualified donors and faecal disposal. Although its cost-effectiveness compared to drug therapies is not high, other GMP interventions for regulating intestinal microecology are more affordable. It is necessary to strengthen the economic benefits and perform cost analysis for the GMP. Second, the acceptance of patients is a challenge, because currently, except for FMT, which is relatively difficult to accept, other GMP interventions have earlier existed, but they have not formed a systematic intervention system for intestinal microecological imbalance. Third, compared to traditional methods, the advantage of GMP is that the new systematic approach to intestinal microecology can be used for diseases that have not been adequately treated in the past; however, the disadvantage is that it requires more complex intestinal microecology theories and more research to approve it for future applications. Fourth is the individualised application of GMPs. As we continue to progress in our research, doctors can prescribe individualised GMPs, such as selecting antibiotics or other medications that have minimal impact on the intestinal microecology, specific exercise prescriptions to improve intestinal microecological imbalances, and specific foods to enhance the diversity of the intestinal microecology.

The difference between gut microbiota prescriptions and probiotics lies in that Gut Microbiota Prescriptions systematically and specifically intervenes through various methods, including diet, exercise, FMT, probiotics, prebiotics, Traditional Chinese Medicine, medications and other methods. Its intervention methods include not just probiotics, but also provide more personalized and precise treatments.

This paper summarises the causes of intestinal microecological imbalance, defines it, and refines the aetiology and classification of intestinal microecological imbalance, GMPs, and detection and intervention methods for intestinal microecological imbalance. Although similar articles or concepts have existed in the past, we are the first to integrate these concepts systematically and to propose the concept of GMP and a GMP intervention strategy that can be applied clinically. However, owing to the complexity and dynamic balance of the intestinal microecology, the following problems still exist and need resolution:

(1) Clear diagnostic criteria for intestinal microecological imbalance: Although this paper broadly defines the framework of intestinal microecological imbalance, it still needs more evidence to prove it.

(2) Although this paper classifies intestinal microecological imbalance, there may be other imbalance types that have not been included.

(3) Different intestinal microecological imbalance types require different interventions for comprehensive treatment but currently lack systematic, individualised, and comprehensive therapies.

(4) Intestinal microecological imbalance is observed in patients and in healthy individuals, such as healthy individuals with short-term disturbances. GMPs can also be used for short-term interventions in healthy individuals with intestinal microecological imbalance, such as dietary and exercise therapies.

(5) Current studies have shown that the intestinal microecological imbalance may not completely recover after 6 months of antibiotic intervention.66–68 For subacute intestinal microecological imbalance, regulation of the imbalance may be possible without antibiotics and using FMT; however, whether 6 months of antibiotics will work for chronic intestinal microecological imbalance remains to be elucidated.

(6) We strongly recommend that all drug inserts be labelled for their effects on intestinal microecology for the rational use of GMPs.

Conclusions

In summary, this review provides an effective method for applying current research on gut microbiota to clinical practice, even though there are still many issues to tackle. It reviews the risk factors that contribute to gut microbiota imbalance, framework of definition, classifications, and detection methods of microbiota imbalance. Additionally, building on previous research, it introduces the idea of gut microbiota prescriptions and summarizes the current potential evidence surrounding these prescriptions, which could help patients with gut microbiota imbalance and promote clinical applications.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by the Special Funding for the Construction of Innovative Provinces in Hunan (2021SK4031).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ramires LC, Santos GS, Ramires RP. et al. The association between gut microbiota and osteoarthritis: does the disease begin in the gut? Int J mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1494. PMID: 35163417; PMCID: PMC8835947. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fassarella M, Blaak EE, Penders J, Nauta A, Smidt H, Zoetendal EG. Gut microbiome stability and resilience: elucidating the response to perturbations in order to modulate gut health. Gut. 2021;70(3):595–605. Epub 2020 Oct 13. PMID: 33051190. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, et al. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature. 2012;491(7423):254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature11465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariño E, Richards JL, McLeod KH, et al. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(5):552–562. doi: 10.1038/ni.3713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almugadam BS, Liu Y, Chen S-M, et al. Alterations of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes individuals and the confounding effect of antidiabetic agents. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:7253978. doi: 10.1155/2020/7253978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortez RV, Taddei CR, Sparvoli LG, et al. Microbiome and its relation to gestational diabetes. Endocrine. 2019;64(2):254–264. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1813-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barcik W, Boutin RCT, Sokolowska M, Finlay BB. The role of lung and gut microbiota in the pathology of asthma. Immunity. 2020;52(2):241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buffington SA, Di Prisco GV, Auchtung TA, et al. Microbial reconstitution reverses maternal diet-induced social and synaptic deficits in offspring. Cell. 2016;165(7):1762–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pluznick JL. The gut microbiota in kidney disease. Science. 2020;369(6510):1426–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.abd8344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raman M, Ahmed I, Gillevet PM, et al. Fecal microbiome and volatile organic compound metabolome in obese humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stripling J, Rodriguez M. current evidence in delivery and therapeutic uses of fecal microbiota transplantation in human diseases-clostridium difficile disease and beyond. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(5):424–432. Epub 2018 Sep 5. PMID: 30384951. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rau S, Gregg A, Yaceczko S, Limketkai B. Prebiotics and probiotics for gastrointestinal disorders. Nutrients. 2024;16(6):778. PMID: 38542689; PMCID: PMC10975713. doi: 10.3390/nu16060778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–484. Epub 2008 Nov 30. PMID: 19043404; PMCID: PMC2677729. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159(4):789–799. PMID: 25417156; PMCID: PMC4255478. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amabebe E, Robert FO, Agbalalah T, Orubu ESF. Microbial dysbiosis-induced obesity: role of gut microbiota in homoeostasis of energy metabolism. Br J Nutr. 2020;123(10):1127–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520000380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guigoz Y, Doré J, Schiffrin EJ. The inflammatory status of old age can be nurtured from the intestinal environment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(1):13–20. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f2bfdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beam A, Clinger E, Hao L. Effect of diet and dietary components on the composition of the gut microbiota. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2795. PMID: 34444955; PMCID: PMC8398149. doi: 10.3390/nu13082795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goh K, Xiao SD. Inflammatory bowel disease: a survey of the epidemiology in Asia. J Dig Dis. 2009;10(1):1–6. PMID: 19236540. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penders J, Thijs C, van den Brandt PA, et al. Gut microbiota composition and development of atopic manifestations in infancy: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Gut. 2007;56(5):661–667. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh KJ, Lee SE, Jung H, Kim G, Romero R, Yoon BH. Detection of ureaplasmas by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with cervical insufficiency. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(3):261–268. PMID: 20192887; PMCID: PMC3085903. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dicks LMT, Geldenhuys J, Mikkelsen LS, Brandsborg E, Marcotte H. Our gut microbiota: a long walk to homeostasis. Benef Microbes. 2018;9(1):3–20. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29022388. doi: 10.3920/BM2017.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proceed Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(26):11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenplas Y, Carnielli VP, Ksiazyk J, et al. Factors affecting early-life intestinal microbiota development. Nutrition. 2020;78:110812. Epub 2020 Mar 25. PMID: 32464473. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galley JD, Yu Z, Kumar P, Dowd SE, Lyte M, Bailey MT. The structures of the colonic mucosa-associated and luminal microbial communities are distinct and differentially affected by a prolonged murine stressor. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(6):748–760. doi: 10.4161/19490976.2014.972241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindell AE, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Patil KR. Multimodal interactions of drugs, natural compounds and pollutants with the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(7):431–443. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00681-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doestzada M, Vila AV, Zhernakova A, et al. Pharmacomicrobiomics: a novel route towards personalized medicine? Protein Cell. 2018;9(5):432–445. Epub 2018 Apr 28. PMID: 29705929; PMCID: PMC5960471. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0547-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomes N, Ferreira-Sa L, Alves N, et al. Uncovering the effects of Giardia duodenalis on the balance of DNA viruses and bacteria in children’s gut microbiota. Acta Trop. 2023;247:107018. Epub 2023 Sep 4. PMID: 37673134. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2023.107018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun K, Gao Y, Wu H, Huang X. The causal relationship between gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes: a two-sample Mendelian randomized study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1255059. PMID: 37808975; PMCID: PMC10556527. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1255059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedroza Matute S, Iyavoo S. Exploring the gut microbiota: lifestyle choices, disease associations, and personal genomics. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1225120. PMID: 37867494; PMCID: PMC10585655. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1225120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin XH, Yang UC, Luo JC, et al. Differences in intestinal microbiota profiling after upper and lower gastrointestinal surgery. J Chin Med Assoc. 2021;84(4):354–360. PMID: 33660622. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amin U, Huang D, Dhir A, Shindler AE, Franks AE, Thomas CJ. Effects of gastric bypass bariatric surgery on gut microbiota in patients with morbid obesity. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2427312. Epub 2024 Nov 17. PMID: 39551972; PMCID: PMC11581163. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2427312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Wang D, Garmaeva S, et al. The long-term genetic stability and individual specificity of the human gut microbiome. Cell. 2021;184(9):2302–2315.e12. Epub 2021 Apr 9. PMID: 33838112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68(8):1516–1526. Epub 2019 May 10. PMID: 31076401; PMCID: PMC6790068. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.GuO Y, He J, Li S, et al. Warm and humid environment induces gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial translocation leading to inflammatory state and promotes proliferation and biofilm formation of certain bacteria, potentially causing sticky stool. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25(1):24. PMID: 39819481; PMCID: PMC11737230. doi: 10.1186/s12866-024-03730-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, et al. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: the North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):775–784. Epub 2017 Mar 21. PMID: 28323273; PMCID: PMC5418558. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Berean KJ, Burgell RE, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Intestinal gases: influence on gut disorders and the role of dietary manipulations. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(12):733–747. Epub 2019 Sep 13. PMID: 31520080. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu H, Wu Z, Xu W, Yang J, Chen Y, Li L. Intestinal microbiota was assessed in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Intestinal microbiota of HBV cirrhotic patients. Microb Ecol. 2011;61(3):693–703. Epub 2011 Feb 1. PMID: 21286703. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z, Wan M, Wang M, Duan J, Jiang S. Modulation of gut microbiota on intestinal permeability: a novel strategy for treating gastrointestinal related diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;137:112416. Epub 2024 Jun 8. PMID: 38852521. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, et al. Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Wijck K, Verlinden TJ, van Eijk HM, et al. Novel multi-sugar assay for site-specific gastrointestinal permeability analysis: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odenwald MA, Turner JR. Intestinal permeability defects: is it time to treat? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1075–1083. Epub 2013 Jul 12. PMID: 23851019; PMCID: PMC3758766. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang J, Ip M, Yang M, et al. The learning curve, interobserver, and intraobserver agreement of endoscopic confocal laser endomicroscopy in the assessment of mucosal barrier defects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(4):785–91e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaezi MF, Choksi Y. Mucosal impedance: a new way to diagnose reflux disease and how it could change your practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):4–7. Epub 2016 Dec 13. PMID: 27958288; PMCID: PMC9003553. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seethaler B, Basrai M, Neyrinck AM, et al. Biomarkers for assessment of intestinal permeability in clinical practice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(1):G11–G17. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00113.2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells JM, Brummer RJ, Derrien M, et al. Homeostasis of the gut barrier and potential biomarkers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312(3):G171–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fasano A. All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20510.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasso JM, Ammar RM, Tenchov R, et al. Gut microbiome-brain alliance: a landscape view into mental and gastrointestinal health and disorders. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14(10):1717–1763. Epub 2023 May 8. PMID: 37156006; PMCID: PMC10197139. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dimidi E, Christodoulides S, Scott SM, Whelan K. Mechanisms of action of probiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota on gut motility and constipation. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(3):484–494. PMID: 28507013; PMCID: PMC5421123. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(4):783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Determinants of symptom pattern in idiopathic severely delayed gastric emptying: gastric emptying rate or proximal stomach dysfunction? Gut. 2007;56(1):29–36. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, Di Lorenzo C, et al. American neurogastroenterology and motility society consensus statement on intraluminal measurement of gastrointestinal and colonic motility in clinical practice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(12):1269–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01230.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanghellini V, Tack J. Gastroparesis: separate entity or just a part of dyspepsia? Gut. 2014;63(12):1972–1978. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mundt MW, Hausken T, Samsom M. Effect of intragastric barostat bag on proximal and distal gastric accommodation in response to liquid meal. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283(3):G681–G686. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breen M, Camilleri M, Burton D, et al. Performance characteristics of the measurement of gastric volume using single photon emission computed tomography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(4):308–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01660.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, et al. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52(9):1271–1277. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frank JW, Sarr MG, Camilleri M. Use of gastroduodenal manometry to differentiate mechanical and functional intestinal obstruction: an analysis of clinical outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(3):339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfe RT, et al. World gastroenterology organisation global guideline: constipation: a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(6):483–487. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820fb914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuo B, McCallum RW, Koch KL, et al. Comparison of gastric emptying of a nondigestible capsule to a radio-labelled meal in healthy and gastroparetic subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(2):186–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rao SS, Kuo B, McCallum RW, et al. Investigation of colonic and whole-gut transit with wireless motility capsule and radiopaque markers in constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(5):537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nurko S, Scott SM. Coexistence of constipation and incontinence in children and adults. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]