Abstract

Invasive and proliferative phenotypes are fundamental components of malignant disease, yet basic questions persist about whether tumor cells can express both phenotypes simultaneously and, if so, what are their properties. Suitable in vitro models that allow characterization of cells that are purely invasive are limited because proliferation is required for cell maintenance. Here, we describe glioblastoma cells that are highly invasive in response to hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF). From this cell population, we selected subclones that were highly proliferative or displayed both invasive and proliferative phenotypes. The biological activities of invasion, migration, urokinase-type plasminogen activation, and branching morphogenesis exclusively partitioned with the highly invasive cells, whereas the highly proliferative subcloned cells uniquely displayed anchorage independent growth in soft agar and were highly tumorigenic as xenografts in immune-compromised mice. In response to HGF/SF, the highly invasive cells signal through the MAPK pathway, whereas the selection of the highly proliferative cells coselected for signaling through Myc. Moreover, in subcloned cells displaying both invasive and proliferative phenotypes, both signaling pathways are activated by HGF/SF. These results show how the mitogen-activated protein kinase and Myc pathways can cooperate to confer both invasive and proliferative phenotypes on tumor cells and provide a system for studying how transitions between invasion and proliferation can contribute to malignant progression.

Keywords: glioblastoma multiforme, hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor, Met

The development and growth of tumor metastasis require that neoplastic cells must either have the potential to shift genetically or epigenetically between proliferative and invasive phenotypes or simply express both phenotypes simultaneously. Thus, many questions about the process of malignant progression remain unanswered, e.g., whether cells in the primary tumor possess malignant properties (1, 2), whether micrometastases are obligatory precursors to frank metastases, and how the heterogeneity of tumor phenotypes contributes to malignant disease (3, 4).

Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) is the ligand for the Met receptor tyrosine kinase (5). In response to HGF/SF, cells expressing Met trigger several signaling cascades that, depending on cell type, mediate a multitude of biological events such as proliferation (6), scattering and migration (7, 8), angiogenesis (9-11), branching morphogenesis (12), and/or growth in soft agar (13). HGF/SF-induced signals and cellular responses are required for the development of the placenta, liver, tongue, diaphragm, limb muscles, and axons during normal embryogenesis (14-17) and for wound healing (18) and organ regeneration (19). Like other tyrosine kinase receptors, but for many more types, Met signaling has been implicated in the etiology and malignant progression of most types of human cancer (5) (www.vai.org/vari/metandcancer). Discovered independently as a mitogen for hepatocytes and as a motility factor for canine kidney cells, in many tumor cell lines, HGF/SF induces both proliferative and invasive responses (20-22). It is not certain whether fixed subpopulations exist within a cell line that are either invasive or proliferative or whether some cells proliferate and invade. Here, we have established in vitro methods to select tumor cells with highly invasive or proliferative phenotypes to allow characterization of the cells and the molecular pathways responsible for each phenotype. We chose to study a Met-expressing human glioblastoma multiforme tumor cell line, because of its unique, highly invasive phenotype in response to HGF/SF. From these cells, we isolated highly proliferative subclones and cells with both proliferative and invasive phenotypes. We have examined these cells in vitro for proliferation, migration, branching morphogenesis (23), and anchorage-independent growth (13), and in vivo tumorigenesis assays in immune-compromised mice. We show that segregation of the proliferative and invasive phenotypes correlate with the selection of signaling pathways activated by HGF/SF. The invasive cells signal through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), whereas highly proliferative cells use the Myc pathway, and the two pathways cooperate in cells with both phenotypes.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents. Parental DBTRG-05MG (DB-P), U373 human glioblastoma cells and HepG2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (catalog no. CRL-2020) and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Human HGF/SF was purified as described in ref. 24. Anti-Met antibody (25H2), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr-202/Tyr-204) monoclonal antibody, and phospho-AKT (Ser-473) antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The antibodies for c-Met (C-28), ERK 2 (D-2), p21 (C-19), Myc (9E10), RAS (C-20), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Thymidine Incorporation Assays. Cells were distributed into 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells per well) with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 24 h. The cells were starved in DMEM without FBS for 48 h, and further incubated with or without HGF/SF for 12 h. One microcurie (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of [3H]thymidine (PerkinElmer) was added 4 h before analysis. Cells were washed with PBS and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured by precipitation of whole cells with chilled 10% trichloroacetic acid, solubilization of precipitates with lysis buffer (0.02 M NaOH/0.1% SDS), suspension in 3 ml of scintillation mixture (Packard Bioscience) and measurement by a liquid scintillation counter (TRI-CARB 3100TR, Packard Bioscience).

Anchorage-Independent Growth in Soft Agar. Cells (1 × 104) were seeded in six-well plates with a bottom layer of 0.7% Bacto agar in DMEM and a top layer of 0.3% Bacto agar in DMEM (13). Fresh DMEM with 10% FBS with or without HGF/SF (100 ng/ml) was added to the top layer of the soft agar. The culture medium was changed twice a week. After 16 d, colonies were stained with 0.005% crystal violet; representative views from triplicate experiments were photographed, and the average number of colonies per well was determined.

Tumorigenesis Assays. Six-week-old female athymic nude (BALB/c, nu/nu) mice were injected with DB-P or DB-A2 (DB-A, a subclone of DB-P) cells. The cells (3 × 106) were suspended in 100 μl of PBS and injected s.c. Tumor volume was monitored every 3 d. Mice were euthanized when the tumors reached a volume of 1,000 mm3 or after 7 weeks of monitoring. Experiments using mice were approved by the Van Andel Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supporting Information. For additional information, see Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results

Selection of HGF/SF-Inducible, Proliferative Subclones. HGF/SF-Met signaling induces both proliferation and invasion as shown in a sampling of tumor cell lines (leiomyosarcoma, glioblastoma, colorectal, and prostate carcinomas) (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Of these tumor cell lines, DB-P cells were highly invasive and showed least proliferative response to HGF/SF (21). To isolate proliferative subclones from DB-P, we plated cells at low density in DMEM supplemented with HGF/SF for 3 weeks, and fast-growing colonies derived from single cells were subjected to further analysis. DB-A2 and DB-A6 subclones were selected for further study because they were most active in thymidine incorporation assays in response to HGF/SF (Fig. 1A) and they showed differences in downstream signaling. DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells showed comparable levels of Met protein in the absence of ligand, but only DB-P cells showed significant Met down-modulation in response to HGF/SF (Fig. 1B). Moreover, DB-A2 cells showed low HGF/SF-dependent Erk phosphorylation compared with DB-P cells, and DB-A6 cells were intermediate.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of DB-P and selected subclones. (A) Thymidine incorporation by DB-P and subclones. Cells were serum-starved for 48 h and then left untreated (SS) or supplemented with 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) and assayed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Western blotting showing Met protein level and activation of downstream signaling. (C) Invasion assay in Matrigel chambers. Cells (2 × 104 per well) were seeded into Matrigel inserts. Control medium (SS) or medium containing 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) was added into the lower chamber. Cells that migrated through Matrigel and attached to the under surface of the filter were counted. The mean values from triplicate experiments (plus 1 SD) are presented. (D) HGF/SF-mediated uPA activation in DB-P and DB-A2 cells. The mean values (plus 1 SD) from three experiments are displayed.

Assays for Invasive and Proliferative Cell Phenotypes. To test whether the activities of DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 were consistent with all invasive and proliferative properties in vitro, we tested them for HGF/SF inducible urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) activity, wound healing-migration, branching morphogenesis, anchorage-independent growth in soft agar, and in vivo for tumorigenicity. The results are summarized in Table 1. In in vitro invasion assays in 3D Matrigel, DB-P cells were most invasive, whereas DB-A2 responded the least, and DB-A6 cells were intermediate (Fig. 1C). We tested the DB-P and DB-A2 cells for HGF/SF-inducible uPA activity (Fig. 1D). Whereas parental cells displayed a 2- to 3-fold induction over basal level, the DB-A2 cells did not respond. Next, DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells were compared in an in vitro wound healing migration assay. Cell sheets were scratched and then incubated in serum-free medium with or without HGF/SF for 24 h. Dramatically, DB-P cells completely filled in the scratched area in 24 h in response to HGF/SF, whereas both DB-A2 and DB-A6 cells were less responsive (Table 1; see also Fig. 8, which is published in supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Table 1. Characterization of DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells.

| Phenotypes | DB-P | DB-A2 | DB-A6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration | ++++ | + | ++ |

| Invasion | ++++ | + | +++ |

| Branching morphogenesis | ++++ | + | ++ |

| uPA/plasmin activity | ++++ | + | N |

| Proliferation | + | +++ | +++ |

| Growth on soft agar | + | +++ | N |

| Tumorigenic in nude mice | + | +++ | N |

| MAPK | ++++ | + | +++ |

| Myc | + | +++ | +++ |

N, not done.

As an additional indicator of invasive potential, HGF/SF characteristically induces branching morphogenesis in certain Met-expressing cell lines when they are cultured in 3D Matrigel. DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells were compared in this assay. A remarkable 85% of DB-P cells formed branches in the presence of HGF/SF. By contrast, <10% of DB-A2 and <30% of DB-A6 cells displayed branching activity (Table 1 and Fig. 2). We conclude that DB-P cells express all of the in vitro characteristics of highly invasive cells (Table 1), whereas DB-A2 cells tested poorly in these assays, and DB-A6 cells, where tested, displayed an intermediate or mixed response. Thus, selecting for a highly proliferative phenotype resulted in significant decreases in HGF/SF-dependent invasion activities.

Fig. 2.

Decreased branching morphogenesis in highly proliferative subclones. (A) Cells growing in 3D Matrigel were treated with 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) or without HGF/SF (C) for 3 d. The number of branching cells per 200 cells was counted, and the mean (plus 1 SD) from three separate counts is presented. (B) Branching morphogenesis after cell growing in 3D Matrigel for 10 d was observed under a phase-contrast microscope.

We performed a soft-agar colony-formation assay comparing DB-P and DB-A2 cells (Fig. 3A). In this assay, DB-P cells were inactive, and no colonies were visualized either in the presence of serum or when supplemented with HGF/SF. In contrast, DB-A2 cells formed small colonies in soft agar in the presence of serum and much larger and more numerous colonies when supplemented with serum plus HGF/SF. This assay does not merely reflect proliferation potential because DB-A2 grew better in serum compared with HGF/SF in proliferation assays (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Anchorage-independent cell growth and in vivo tumorigenic assay. (A) Colony formation assay. DB-P or DB-A2 cells (2.5 × 104 cells per well) were grown in soft agar with 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) or without HGF/SF (C) for 16 d. (Left) Representative areas from triplicate experiments are presented. Visible colonies (>0.5 mm in diameter) were counted after crystal violet staining. (Right) The mean value (plus 1 SD) of three independent experiments is shown. (B) Enhanced tumorigenic activity of DB-A2. DB-P or DB-A2 cells (3 × 106 cells per mouse) were s.c. injected into 6-week-old athymic female (nu/nu) mice. Tumor size was estimated by caliper measurements after 8 d and then at 3-d intervals. The mean volumes (plus 1 SD) of tumors from nine mice for each group are presented as a function of time after injection.

Anchorage-independent growth in soft agar is often predictive of tumorigenicity in vivo; we therefore inoculated DB-P and DB-A2 cells s.c. into athymic nude mice and compared the rates of tumor growth (Fig. 3B). DB-A2 xenografts grew significantly faster than DB-P xenografts, the latter reaching a mean estimated volume nearly six times that of the DB-P xenografts by 28 d of growth (P < 0.05).

DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6: Specific Differences in Signaling Pathways. We next studied the signaling induced by HGF/SF. As indicated above, DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 exhibited different responses to HGF/SF with regard to Met down-modulation and Erk phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). We also show slight differences in the kinetics of Met phosphorylation after HGF/SF stimulation (Fig. 4A) and in the abundance of Met protein expression after HGF/SF stimulation, indicating that the turnover of Met is regulated differently.

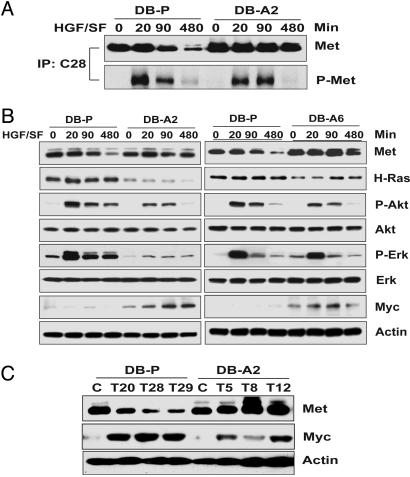

Fig. 4.

Different signaling pathways are induced by HGF/SF in DB-P and proliferative subclones. (A) HGF/SF-induced phosphorylation of Met receptor in DB-P and DB-A2 cells. Total Met immunoprecipitates recovered with polyclonal antibody C-28 were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies directed against Met (25H2) or phosphotyrosine (4G10). (B) The activation of signal pathways in DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells. (C) Myc expression is enhanced during DB-P tumorigenesis. DB-P or DB-A2 cells before (C) or after (T) growing in nude mice were analyzed by immunoblotting to estimate levels of total cellular Met, Myc, and β-actin. DB-P tumors (T20, T28, and T29) were collected after 49 d, and DB-A2 tumors (T5, T8, and T12) were collected after 31 d of growth.

We further evaluated signal pathways downstream from Met in DB-P, DB-A2, and DB-A6 cells as a function of HGF/SF (Fig. 4B). We detected higher levels of Ras in DB-P cells than DB-A2 cells, and HGF/SF induced significant phosphorylation of Erk and Akt in these cells (Fig. 4B Left). By contrast, DB-A2 cells showed dramatically higher Myc protein induction after HGF/SF exposure compared with DB-P cells. Comparing signaling pathways in DB-P cells and DB-A6 cells (Fig. 4B Right), there was less difference in the level of H-Ras between the two cell types, but Myc expression was greater in the DB-A6 cells. Taken together, our in vitro data suggest that for these tumor cells, the Ras/MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways are associated with the phenotype of the invasive cells displayed by DB-P and DB-A6 cells, but not by the highly proliferative DB-A2 cells. In DB-A2 cells, Myc expression is associated with the proliferative phenotype.

DB-A2 cells showed significant growth as tumor xenografts (Fig. 3B), which indicated that Myc maybe important for supporting tumor growth. We examined the tumor xenografts generated by DB-A2 and DB-P cells for the expression of Myc (see Fig. 4C). All tumors were collected when they were ≈1,000 mm3. The DB-A2 tumors were harvested at 31 d, whereas the DB-P tumors took 49 d to reach the same size. High levels of Myc protein were detected in all tumors, but not in parental DB-P or DB-A2 cells in the absence of HGF/SF treatment, indicating that Myc expression may be associated with a selective advantage for tumor growth.

Consequences of Ectopic Myc Expression in DB-P Cells. We further tested whether Myc was important for the proliferative phenotype by expressing it ectopically in DB-P cells. Using a CMV promoter/leader sequence, we showed that Myc mRNA was present by RT-PCR in two transfected clones (Pmyc-1 and Pmyc-2) (Fig. 5A), and Myc protein was overexpressed (Fig. 5B). By thymidine incorporation, both Pmyc-1 and Pmyc-2 cells displayed significantly higher proliferative responses to serum and/or serum supplemented with HGF/SF than DB-Pc cells, and the thymidine incorporation approached that of the highly proliferative DB-A2 subclone (Fig. 5C). However, ectopic Myc expression did not influence HGF/SF mediated invasion (Fig. 5D), and both Pmyc clones remained highly invasive. By contrast, Myc expression substantially enhanced colony formation in soft agar (Fig. 5E). Thus, the Pmyc-1 and -2 expressing cells displayed a phenotype indistinguishable from the mixed phenotype, DB-A6 cells.

Fig. 5.

Consequences of Myc overexpression in DB-P cells. (A) Ectopic expression of Myc mRNA in transfected DB-P clones. The expression of ectopic myc (cmv-myc) and endogenous myc (Endo-myc) was examined by RT-PCR. (B) Expression of Myc protein in transfected clones assayed by immunoblotting. (C) Thymidine incorporation assay showing increased DNA synthesis in Myc-expressing clones. Cells cultured with (FBS) or without serum (SS) were left untreated (SS and FBS) or treated with HGF/SF (SS-HGF and FBS-HGF) for 12 h. (D) In vitro invasion assay of DB-Pc and myc-expressing clones. (E) Enhanced colony formation activity on soft agar in Myc-expressing clones. Cells (1 × 104 cells per well) were grown in soft agar and feed with DMEM supplemented with serum alone (C) or with HGF/SF (HGF) for 16 d. Visible colonies >0.5 mm in diameter were counted after crystal violet staining. The mean value (plus 1 SD) of three independent experiments is presented.

Selection of Invasive Revertants of DB-A2. We asked whether invasive revertants of the highly proliferative DB-A2 cells could be selected to see whether they have signaling properties of DB-P cells. We were concerned that the proliferation required for maintaining the “invasive” cells would act negatively in their selection. However, the proliferation, which occurs with invasion-specific branching morphogenesis as with DB-P cells (Fig. 2 and Table 1), should not. Invasive cells were selected from DB-A2 cells by using branching morphogenesis conditions. DB-A2 cells were cultured in 3D Matrigel, supplemented with HGF/SF for 1 week. Rare branching clusters (1/5,000 cells plated) were selected and expanded to obtain highly branching subclones. In branching morphogenesis assays, >80% of cells selected as subclones from the DB-A2 cells (A2-BH6 and A2-BH7) showed HGF/SF-induced branching activity indistinguishable from invasive DB-P cells (Fig. 6A) and extensive HGF/SF specific branching structures were observed after 1 week (Fig. 6B). Moreover, in response to HGF/SF, the A2-BH6 and A2-BH7 cells were highly invasive (Fig. 6C) and expressed levels of uPA-plasmin activity equivalent to DB-P cells (Fig. 6D). However, the A2-BH6 and A2-BH7 cells showed thymidine incorporation activity intermediate between the proliferative DB-A2 and the invasive DB-P cells (Fig. 6E), suggesting they were more similar to the DB-A6 mixed phenotype. This similarity was more obvious from the levels of HGF/SF-induced Erk and Akt phosphorylation, higher than DB-A2 but less than DB-P cells (Fig. 6F). The presence of Myc in A2-BH7 cells was similar also to DB-A2 cells. These results further show that the MAPK and Myc pathways partition with the invasive and proliferative phenotypes, respectively. We also show that shifting from one to the other phenotype is easily accomplished with this cell line.

Fig. 6.

Characterization of highly invasive revertants from DB-A2 cells. (A) Branching morphogenesis assay. Cells were treated with 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) or without treatment (C) for 3 d. The number of branching cells per 200 cells was counted under a microscope, and the mean (plus 1 SD) from three separate counting is presented. (B) Branching morphogenesis of A2-BH7 cells after cell growing for 7 d in 3D Matrigel was observed under a phase-contrast microscope. (C) In vitro invasion assay. Control medium (SS) or medium containing 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) was added into the lower chamber. The mean number of invading cells from triplicate experiments (plus 1 SD) is presented. (D) HGF/SF-mediated uPA activation in DB-A2 revertant. The mean values (plus 1 SD) from three experiments are displayed. (E) Thymidine incorporation assay. Cells were serum-starved and untreated (SS) or supplemented with 100 ng/ml HGF/SF (HGF) for 12 h. (F) The activation of signal pathways in DB-P, DB-A2, and A2-BH7 cells. Total cell lysates were resolved by electrophoresis and analyzed by immunoblotting.

HGF/SF-Met Induced Proliferation/Invasion in Human Tumor Cell Lines. To determine whether cell proliferation and invasion phenotypes and the respective MAPK (invasion) and Myc (proliferation) are separable and selectable from other tumor cell populations, we isolated from U373 glioblastoma tumor cells, subclones with greater proliferative potential than the parental cells, by using the same selection procedure as for DB-A2 (Fig. 9 A and B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Subclone U373-C3 and subclone U373-C4 exhibited differences in thymidine incorporation. After HGF/SF treatment, Myc expression in U373-C4 cells was higher. However, the activation of Erk in the two subclones was comparable.

By using the selection method, we also obtained a more proliferative subclone, G2-L4, from a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2. HGF/SF does not induce thymidine incorporation in parental HepG2 cells, but does in G2-L4 cells (Fig. 9C).

By contrast, the invasive potential of subclone G2-L4 was lower than the parental cells (Fig. 9D). Consistent with our glioblastoma studies, Erk activation was much more pronounced in the more invasive parental HepG2 cells, whereas the induction of Myc was more prominent in G2-L4 cells. Thus, after one selection, we observed preferential selection for Myc with HGF/SF-mediated proliferation (Fig. 9E), suggesting that it is not an uncommon property of tumor cells.

Discussion

Invasive neoplasms arise from transformed cells through clonal expansion of cells having a selective advantage (25-27). Genomic instability, both genetic and epigenetic, fuels the process whereby cells with proliferative and invasive potential eventually emerge. The activation of oncogenes and functional inactivation of tumor suppressor genes causes a loss of growth regulation, which is characterized by proliferation and subsequent invasion. Although many of the genes and pathways responsible for oncogenic transformation are known, the mode of selection and how they contribute mechanistically to malignant progression is less clear. A very simple model is that the progeny of proliferating cells in the primary tumor acquires an invasive potential, and that these cells after local invasion or migration to new sites again become proliferative but may retain the invasive phenotype.

Here, we show that HGF/SF dependent highly proliferative cells can be selected from invasive human glioblastoma cells and that these proliferative cells easily revert to an invasive phenotype. The in vitro biological activities of invasion, uPA-plasmin activation, wound migration, and branching morphogenesis appropriately partition to the invasive cells, whereas proliferation, growth in soft agar, and in vivo growth as tumor xenografts group with the proliferative phenotype (Table 1). We show that HGF/SF exposure mediates both the invasive and proliferative phenotypes, confirming that both can result from Met activation. The downstream signaling pathways with these disparate phenotypes are quite distinct and appear to act independently. Although they may coexist in the same cell framework, they vary in their responsiveness to HGF/SF. The HGF/SF-responsive proliferative phenotype is associated with enhanced Myc expression, whereas the invasive phenotype displays enhanced signaling through the MAPK pathway. Moreover, cells with both phenotypes such as DB-A6 or DB-P cells ectopically expressing Myc (e.g., Pmyc, Fig. 5), and those cells selected as invasive revertants of highly proliferative cells (A2-BH7, Fig. 6), also grow in soft agar and coexpress both pathways.

Previously, we have shown that, in human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell lines, there is a significant variation in response to HGF/SF (21), ranging from highly proliferative to invasive (21). DB-P cells were derived from a patient with glioblastoma multiforme (28). HGF/SF efficiently induces migration and invasion in DB-P and in other glioblastoma multiforme cell lines (21). Nonetheless, we readily isolated subclones from the DB-P cells that are highly proliferative in response to HGF, suggesting that such cells exist within the parental population. The selection of highly proliferative and tumorigenic subclones may mimic events associated with malignant progression in vivo but, like DB-A6 cells, most tumor cells in vivo are likely to possess both phenotypes. Interestingly, the DB-A2 proliferative responses to either serum or HGF/SF are indistinguishable (data not shown), but HGF/SF does enhance growth in soft agar (Fig. 3A), showing anchorage independent growth is facilitated by Met signaling. We have shown that HGF/SF induced cell growth in soft agar is mediated through Stat 3 (13).

Our previous studies (23, 29) and those of others (22, 30) show that Met can contribute to both tumor initiation and progression. Here, we show that tumor growth and invasion are two distinct processes directed by different molecular signaling pathways controlled by the same hierarchal Met receptor, supporting the idea that Met-mediated activation of specific signaling pathways is required to fulfill distinct cellular responses (17, 31). We observed in this study with cell lines of different types that the high proliferative rate of DB-A2, DB-A6, U373-C4, and G2-L4 cells correlates with the up-regulation of Myc protein by HGF/SF. Ectopic expression of Myc in DB-P cells also increases their proliferation rate, confirming an essential role of Myc in mediating HGF/SF-induced proliferation. These results are consistent with previous reports that Myc is required for HGF/SF stimulation of cell cycle progression through G1 phase in primary hepatocytes and glioblastoma cells (32, 33) and the more recent study showing Met and Myc synergize in tumorigenesis (34). Although not rigorously characterized, Myc mRNAs did not appear to be different in DB-P and DB-A2 cells (data not shown), and other mechanisms like ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis may be involved in the regulation of the Myc protein level (35, 36). Thus, accumulation of Myc protein could be due to an increase in the half-life in glioblastoma multiforme cells (37). Myc degradation can be blocked by Ras/MAPK-mediated signaling (38). However, the Myc protein level is low in DB-P cells, even though HGF/SF activates both MAPK and Akt pathways.

Interestingly, the DB-P cells may help to explain the phenotype of micrometastatic cells. Micrometastatic cells appear to be in a dormant, low proliferative state (39), perhaps proliferating as in the branching morphogenesis mode (Fig. 2) (40). We postulate that the highly invasive DB-P cells, which grow slowly compared with DB-A2 cells (Fig. 3), are like micrometastasis in vivo. However, there is a shift to the more rapidly growing in Myc-expressing cells.

Cell invasion requires the complex coregulation of cytoskeletal reorganization and cell motility as well as proteolysis and interaction with the extracellular matrix, all activities measured in our “invasive” assays (Table 1). This invasive activity extends as well to the identification of the MAPK and Akt signaling in the DB-P cells (Fig. 4). The requirement of the MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways for scattering and migration is well known (41-46). Moreover, treating DB-P cells with a combination of MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors completely blocked HGF/SF mediated cell invasion in vitro (data not shown). MAPK signaling may also contribute to cell invasion by up-regulating uPA and uPA receptor (23, 47, 48). Significant uPA activity was detected after HGF/SF stimulation of highly invasive DB-P cells (Fig. 1 and Table 1) but not with the poorly invasive DB-A2 cells. Moreover, high MAPK and uPA activity was restored in the invasive revertants of DB-A2 cells (A2-BH7, Fig. 6). Modest MAPK activation is required for cell cycle reentry, whereas high activity can induce cell cycle arrest or senescence (49). For many years, it has been known that Myc can cooperate with Ras to induce cellular transformation (50), and mice carrying both activated v-Ha-Ras and Myc transgenes show dramatic acceleration of tumor formation. Our study strongly suggests that the cooperation of MAPK and Myc genes may contribute to malignant progression through regulating the selection of invasive and proliferative phenotypes that is essential for successful formation and growth of metastases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to the memory of our friend and colleague, Dr. Han-Mo Koo. We thank Dr. Carrie Graveel for her comments on the manuscript, Dr. David Petillo and Ping Zhao for their help, and David Nadziejka and Michelle Reed for assistance with preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor and through the generosity of the Jay and Betty Van Andel Foundation.

Abbreviations: DB-P, parental DBTRG-05MG cells; DB-An, subclones of DB-P; HGF/SF, hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator.

References

- 1.Liotta, L. A. & Stetler-Stevenson, W. G. (1991) Cancer Res. 51, Suppl. 18, 5054s-5059s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. (2000) Cell 100, 57-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernards, R. & Weinberg, R. A. (2002) Nature 418, 823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein, C. A. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 29-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birchmeier, C., Birchmeier, W., Gherardi, E. & Vande Woude, G. F. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 915-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura, T., Nishizawa, T., Hagiya, M., Seki, T., Shimonishi, M., Sugimura, A., Tashiro, K. & Shimizu, S. (1989) Nature 342, 440-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoker, M., Gherardi, E., Perryman, M. & Gray, J. (1987) Nature 327, 239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidner, K. M., Arakaki, N., Hartmann, G., Vandekerckhove, J., Weingart, S., Rieder, H., Fonatsch, C., Tsubouchi, H., Hishida, T., Daikuhara, Y., et al. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 7001-7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bussolino, F., Di Renzo, M. F., Ziche, M., Bocchietto, E., Olivero, M., Naldini, L., Gaudino, G., Tamagnone, L., Coffer, A. & Comoglio, P. M. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 119, 629-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen, E. M., Lamszus, K., Laterra, J., Polverini, P. J., Rubin, J. S. & Goldberg, I. D. (1997) Ciba Found. Symp. 212, 215-226, discussion 227-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, Y.-W., Su, Y., Volpert, O. V. & Vande Woude, G. F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12718-12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montesano, R., Matsumoto, K., Nakamura, T. & Orci, L. (1991) Cell 67, 901-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, Y. W., Wang, L. M., Jove, R. & Vande Woude, G. F. (2002) Oncogene 21, 217-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt, C., Bladt, F., Goedecke, S., Brinkmann, V., Zschiesche, W., Sharpe, M., Gherardi, E. & Birchmeier, C. (1995) Nature 373, 699-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bladt, F., Riethmacher, D., Isenmann, S., Aguzzi, A. & Birchmeier, C. (1995) Nature 376, 768-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caton, A., Hacker, A., Naeem, A., Livet, J., Maina, F., Bladt, F., Klein, R., Birchmeier, C. & Guthrie, S. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 1751-1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maina, F., Pante, G., Helmbacher, F., Andres, R., Porthin, A., Davies, A. M., Ponzetto, C. & Klein, R. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 1293-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe, S., Hirose, M., Wang, X. E., Maehiro, K., Murai, T., Kobayashi, O., Nagahara, A. & Sato, N. (1994) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199, 1453-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higuchi, O. & Nakamura, T. (1991) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 176, 599-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gherardi, E. & Stoker, M. (1991) Cancer Cells 3, 227-232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koochekpour, S., Jeffers, M., Rulong, S., Taylor, G., Klineberg, E., Hudson, E. A., Resau, J. H. & Vande Woude, G. F. (1997) Cancer Res. 57, 5391-5398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birchmeier, W., Brinkmann, V., Niemann, C., Meiners, S., DiCesare, S., Naundorf, H. & Sachs, M. (1997) Ciba Found. Symp. 212, 230-240, discussion 240-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffers, M., Rong, S. & Vande Woude, G. F. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1115-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rong, S., Jeffers, M., Resau, J. H., Tsarfaty, I., Oskarsson, M. & Vande Woude, G. F. (1993) Cancer Res. 53, 5355-5360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowell, P. C. (1976) Science 194, 23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fialkow, P. J. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 458, 283-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fearon, E. R., Hamilton, S. R. & Vogelstein, B. (1987) Science 238, 193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruse, C. A., Mitchell, D. H., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B. K., Franklin, W. A., Morse, H. G., Spector, E. B. & Lillehei, K. O. (1992) In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 28, 609-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rong, S., Segal, S., Anver, M., Resau, J. H. & Vande Woude, G. F. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 4731-4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meiners, S., Brinkmann, V., Naundorf, H. & Birchmeier, W. (1998) Oncogene 16, 9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller, M., Morotti, A. & Ponzetto, C. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1060-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skouteris, G. G. & Schroder, C. H. (1996) Biochem. J. 316, 879-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter, K. A., Hossain, M. A., Luddy, C., Goel, N., Reznik, T. E. & Laterra, J. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2703-2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welm, A. L., Kim, S., Welm, B. E. & Bishop, J. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4324-4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spencer, C. A. & Groudine, M. (1991) Adv. Cancer Res. 56, 1-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salghetti, S. E., Kim, S. Y. & Tansey, W. P. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 717-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shindo, H., Tani, E., Matsumuto, T., Hashimoto, T. & Furuyama, J. (1993) Acta Neuropathol. 86, 345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sears, R., Leone, G., DeGregori, J. & Nevins, J. R. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 169-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolteus, A. J., Berens, M. E. & Pilkington, G. J. (2001) Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 1, 225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, Y. W. & Vande Woude, G. F. (2003) J. Cell Biochem. 88, 408-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridley, A. J., Comoglio, P. M. & Hall, A. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1110-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartmann, G., Weidner, K. M., Schwarz, H. & Birchmeier, W. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21936-21939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Royal, I. & Park, M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27780-27787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potempa, S. & Ridley, A. J. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 2185-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueoka, Y., Kato, K., Kuriaki, Y., Horiuchi, S., Terao, Y., Nishida, J., Ueno, H. & Wake, N. (2000) Br. J. Cancer 82, 891-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vial, E., Sahai, E. & Marshall, C. J. (2003) Cancer Cell 4, 67-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pepper, M. S., Matsumoto, K., Nakamura, T., Orci, L. & Montesano, R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 20493-20496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ried, S., Jager, C., Jeffers, M., Vande Woude, G. F., Graeff, H., Schmitt, M. & Lengyel, E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16377-16386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woods, D., Parry, D., Cherwinski, H., Bosch, E., Lees, E. & McMahon, M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5598-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Land, H., Parada, L. F. & Weinberg, R. A. (1983) Nature 304, 596-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.