Abstract

Aim

To provide a comprehensive overview of how stroke nurses manage solid medication (SM) delivery to patients with post‐stroke dysphagia.

Design

Cross‐sectional study.

Methods

A self‐administered online survey was carried out among nurses in German‐speaking countries between September and December 2021.

Results

Out of a total of 754 responses, analysis was conducted on 195 nurses who reported working on a stroke unit. To identify swallowing difficulties in acute stroke care, 99 nurses indicated routinely administering standardised screenings, while 10 use unvalidated screenings, and 82 are waiting for a specialist evaluation. Regardless of whether screening methods are used or not, most preferred a non‐oral route of medication administration for patients with suspected dysphagia. None of the respondents reported administering whole SMs orally to patients. If screening methods indicate dysphagia, approximately half of the respondents would modify SMs. Participants who stated to use the Gugging Swallowing Screen managed the SM intake guided by its severity levels. One‐third of the group who awaited assessment by the dysphagia specialist provided modified medication before the consultation.

Conclusion

Most of the nurses on stroke units use swallowing screens and avoid the administration of whole SMs in post‐stroke dysphagia. In addition to the non‐oral administration, SMs are modified if dysphagia is suspected. Precise guidance on the administration of SM is needed, based on screening tests and prior to expert consultation.

Trial and Protocol Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: Registration ID: NCT05173051/ Protocol ID: 11TS003721.

Implications for the profession and/or patient care

The present paper serves to alert nurses to the issue of patient safety when administering medication for acute stroke‐induced dysphagia.

Impact

SM delivery after acute stroke‐induced dysphagia is often neglected. While nurses are aware of the risk associated with dysphagia and would not give whole SMs to patients, the modification of tablets and their administration with semisolids are common.

Reporting Method

This study was reported according to the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS).

Keywords: deglutition disorders, dysphagia, medication intake, pills, solid medication, stroke

What does this paper contribute to the wider global community?

Nurses often face challenges administering SMs to patients with swallowing difficulties.

In the absence of scientific evidence, it is common practice not to administer whole SMs to dysphagic stroke patients but rather to modify them.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the second‐leading cause of death worldwide and the third‐leading cause of severe disability in old age (Feigin, 2021). Since up to 75% of patients initially suffer from dysphagia, special attention and care regarding oral intake of food, liquids and medication are needed (Banda et al., 2022). Several guidelines recommend the implementation of screening protocols in a stroke unit to identify the high‐risk population and prevent complications such as aspiration pneumonia. Additionally, most of the recently published guidelines emphasise the importance of evaluating the swallowing ability of solid medications (SM) (Dziewas et al., 2021; NICEguidline (NG128), 2019; Powers et al., 2019). Administering medications to patients is decisive in acute stroke treatment in the first few days. For optimal recovery from a stroke, it is crucial to ensure the consistent, comprehensive and safe administration of oral medications, a responsibility that lies with healthcare professionals. Water swallowing screening protocols and multi consistency screening tests were validated for identifying dysphagia and/or aspiration risk (Boaden et al., 2021). However, no screening tool or guidance for oral medication intake in stroke patients with dysphagia is available. The most commonly used method is to crush or divide SMs and mix them with a sweet and mashed texture, which could lead to harmful medication errors (Daibes et al., 2023). In summary, SM delivery and management are currently based on traditional methods that lack evidence‐based support.

2. BACKGROUND

Dysphagia presents a considerable challenge for approximately 50% of individuals who have experienced an acute stroke (Banda et al., 2022). Incorporating standardised swallowing screening and instrumental assessment tools within stroke units has been shown to significantly reduce complications such as the prevalence of pneumonia (Boaden et al., 2021). However, many dysphagia screening tools, especially water screening tests, only provide a binary outcome: either a positive or negative result for the occurrence of dysphagia or aspiration risk, which results in either oral intake or nil per os (NPO). Multi consistency screening tests aim to evaluate a variety of textures to gather information on their swallowability. The Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS), for example, is a widely used multi consistency test to assess dysphagia severity and to suggest dietary changes, and medication use (Trapl et al., 2007; Warnecke et al., 2017). Up to the knowledge of the authors, no screening tool explicitly examines the ability to swallow solid dosage forms. Thus, it is currently unknown whether the use of a screening tool assists stroke nurses in deciding how to administer SMs.

The fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) and videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) are gold standards for dysphagia evaluation. These methods enable detailed analysis of bolus processing and help healthcare professionals to identify any pathophysiology that may affect swallowing safety and efficiency. The implementation of instrumental assessment remains relatively scarce, though its application in stroke units is progressively growing. Due to the fact that dysphagia screenings do not directly evaluate the swallowing ability of SMs and that instrumental assessment cannot be performed for every patient, the management of medication intake represents a gap in post‐stroke dysphagia.

An exploratory literature search revealed that only three studies have delved into the use of medication intake for stroke patients with FEES (Buhmann et al., 2019; Carnaby‐Mann & Crary, 2005; Schiele et al., 2015). Schiele etal. (2015) investigated stroke patients in a subacute stage. They discovered the risk of aspiration was significantly higher when tablets were ingested with both water and pudding, compared to swallowing these consistencies separately. Another study was conducted by Carnaby et al. on a cohort of 36 patients who presented with dysphagia resulting from various conditions. They evaluated the swallowing physiology and safety between a conventional tablet and a new method of tablet transportation. They found out that patients with dysphagia demonstrated significantly longer total swallow durations, a higher number of swallows per tablet and the need for fluid to assist in the clearance of the conventional tablet (Carnaby‐Mann & Crary, 2005). Buhmann enrolled 118 patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) and 32 controls and used FEES to investigate their ability to swallow four placebo tablets. The study revealed 28% of patients with PD exhibited a significant impairment in their capacity to swallow pills, with capsules being identified as the easiest form to ingest, whereas oval tablets posed the greatest difficulty (Buhmann et al., 2019).

It is worth noting that Yamamoto et al. (2014) conducted the only VFSS study on the behavioural performances of tablet swallowing, exclusively on healthy young participants. The group demonstrated that four different types of tablets affected the swallowing function in terms of total number of swallows, electromyographic burst patterns and location of remaining tablets. Another study validated a questionnaire for self‐assessment of pill swallowing and compared it with the VFSS. However, they only focused on the tablet's transit time, and they included patients with different causes of dysphagia (Nativ‐Zeltzer et al., 2019).

It is commonly observed that SMs are modified in dysphagic patients (e.g. crushing, breaking, and opening of tablets and capsules), which may lead to numerous issues, such as decreased accuracy of dose, increased toxicity, reduced stability and alteration of pharmacokinetics (Blaszczyk et al., 2023; Wirth & Dziewas, 2019). In a scoping review, two researchers found that nurses have a particularly high level of uncertainty when administering tablets to dysphagic patients. According to one of the included studies, crushing is done automatically by 77% of caregivers. There is a lack of knowledge about which SMs should not be crushed and, above all, with which accompanying textures they should be administered (Masilamoney & Dowse, 2018). Based on another study conducted across multiple centres, it was found that patients with dysphagia have a higher incidence of tablet changes and administration errors, resulting in increased complications compared to those without dysphagia (Kelly et al., 2012). A recently published study investigated the knowledge and practice regarding mixing medications with food in 200 nurses via face‐to‐face interviews. They found out that 88% of the participants, working on different wards, modified solid dosage forms prior to administration to patients. Approximately 35% of nurses revealed that they felt inadequately trained to carry out this practice (Daibes et al., 2023). In contrast, To et al. (2013) performed a survey at a large hospital in Melbourne to investigate the healthcare staff's understanding of managing oral medications in patients with restrictions on oral intake after stroke. They demonstrated that almost 10% of the respondents would give oral medication to a nothing‐by‐mouth patient after a stroke. Another article referring to stroke patients suggests that a multidisciplinary team should determine the most appropriate way for the patient to take their medication. Additionally, the author advises that alternative administration methods be considered for patients who cannot swallow solid oral dosage forms (O'Hara, 2015). Due to the scarcity of literature on stroke patients, it remains unclear how stroke nurses manage oral medication administration based on their experience and specialisation in post‐stroke dysphagia.

An additional significant concern is the texture of co‐administered vehicles with which solid or altered medications are provided. In clinical practice, thickened water, apple sauce or milk products are frequently utilised for this purpose (Manrique et al., 2014). Some research has shown that applesauce and orange juice can greatly alter the absorption and bioavailability of some medicines (Jackson & Naunton, 2017; Moses, 2020; Yin et al., 2011). Furthermore, Cichero (2013) were one of the first authors who showed a negative influence of thickeners on drug absorption. Fluids often need to be thickened in dysphagic patients to reduce the flow rate and prevent aspiration. Therefore, the use of thickeners is common practice in hospitals and geriatric wards. The adverse impact of a thickened consistency on the efficacy of medication remains largely unrecognised and is therefore seldom taken into account in clinical practice (Cichero, 2013).

To thoroughly investigate nurses' management of oral medication intake, numerous studies have been conducted across various populations using qualitative research methods, including questionnaire surveys, observations, and interviews. All of these studies demonstrated that nurses, in general, feel inadequately trained and informed, as well as there exists a lot of uncertainty, and that tablet modification is common practice (Cordonier et al., 2013; Fields et al., 2015; Kelly et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016; Mc Gillicuddy, Crean, et al., 2017). Despite the specialised role of stroke nurses in the field of dysphagia, the extent of information on medication management that could be obtained was limited.

In conclusion, the current body of evidence is inadequate to represent stroke nurses´ practices in administering SMs to acute dysphagic patients. Additionally, it is unknown how nurses manage SM intake based on a dysphagia screening tool or while awaiting specialist evaluation.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aims

The present study is part of a larger project that aims to examine the oral intake of solid dosage forms in patients with acute stroke and dysphagia within the first week after admission. It includes two web‐based surveys and a clinical observational study on medication intake. The primary aim of the presented survey was to explore how nurses manage the administration of SMs in acute stroke patients with dysphagia. A secondary objective is to investigate how standardised dysphagia screening tests, particularly the multi consistency screening test GUSS, impacts SM administration management in the hyperacute and acute stroke stage.

3.2. Design

A quantitative cross‐sectional study was conducted using a self‐administered web survey among nurses working on stroke units in German‐speaking countries.

3.3. Population

The study encompassed certified nurses who were employed in a stroke unit. A convenience sampling technique was used to obtain a sufficient number of participants. To reach nursing staff, all 387 stroke units in German‐speaking countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) were contacted. In Austria, permission was obtained from the different holding companies in the federal provinces to distribute the questionnaire to the 39 stroke units. Two healthcare corporations from two different federal provinces declined to participate. Out of the 338 stroke units in Germany, 178 with eight or more stroke unit beds were directly contacted and requested via the hospital directors or the heads of stroke units that the questionnaire be forwarded. Efforts were made to contact stroke nurses across the 10 stroke units in Switzerland through the ‘Swiss Nurse Leader’ nursing association. Furthermore, a link to the questionnaire was circulated using a snowball sampling approach in specialist groups on national and international social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn) as part of a passive survey. Contact was also made with professional associations and other specialist societies (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie e.V. (DGN), Deutsche Schlaganfall‐Gesellschaft (DSG), Swiss Nurse Leaders, Swiss Dysphagia Association, Nursing Network, Austrian Health and Nursing Association/ Österreichischer Gesundheits‐ und Krankenpflegeverband).

3.4. Data collection

A structured online questionnaire was developed with the assistance of the survey tool Qualtrics (Qualtrics, 2005 ). The superordinate topics included the usage and types of screening methods, non‐oral or oral medication management, responsibility for non‐oral and/or oral administration of medication, methods used for medication delivery (including accompanying textures) and self‐evaluated questions regarding the knowledge of medication administration. The questionnaire featured Likert scales and multi‐categorical response formats. Where needed, the questionnaire employed a mix of closed and open‐ended questions, along with ‘other’ and ‘comment’ options, to guarantee that no vital additional information was missed. One question, pertaining to the utilisation of accompanying boluses for medication delivery, was displayed in a random order so that each respondent encountered a different sequence of suggestions.

A pretest of the questionnaire was performed by 13 healthcare professionals, and the questionnaire was adapted according to their suggestions. The final version was distributed between September 2021 and December 2021.

3.5. Data analysis

The questionnaire consisted of 31 questions, with 21 being identical for all participants. Employing skip logic throughout the survey, participants were grouped based on the screening methods used on their stroke units: water swallowing tests (WST), multi consistency tests (MCT), unvalidated screenings (US), no screening (NS), waiting for the specialist (WS). To especially investigate the impact of severity classification and dietary recommendations of the GUSS test results on medication administration, the multi consistency group was divided into two subgroups based on whether or not they used the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS). Data from the GUSS group was analysed separately. Due to lack of responses, the group ‘No screening’ and four respondents who did not specify their screening method (‘Not specified’) were excluded from further statistical analysis and diagrams.

Missing data were presented in the diagrams as ‘not specified’ or ‘others’. Missing values were common since most questions allowed for multiple response options. Therefore, the total number of answers per sub‐question was tallied rather than shown the total answers for each person individually. All results were presented in percentages or absolute numbers, separately for each group.

All data were exported from Qualtrics to IBM SPSS Statistics version 28. Descriptive diagrams were generated with the Qualtrics questionnaire software but also via Excel for Mac (Version 16.78) or SPSS.

3.6. Ethical consideration

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Province of Lower Austria on 15th of June 2021 (No: GS4‐EK‐4/698–2021).

The participants were required to acknowledge a declaration regarding data protection and consent actively. Participation was fully anonymous, to the point where even the IP address could not be traced.

4. RESULTS

A total of 754 nurses participated in the survey. Out of the respondents, 195 (25.9%) indicated they worked in stroke units and were thus incorporated into the analysis. Among these, 66.7% (n = 133) participated from Germany, 24.1% (n = 47) from Austria and 9.2% (n = 18) from Switzerland. 80% of the stroke nurses stated that they had completed training as qualified registered nurses. This training typically spans a period of 3–4 years in German‐speaking countries. Only 3.6% had less than 3 years of education (nurse assistant, auxiliary nurse), while 16.4% reported having completed other equivalent training in the care sector.

Of the respondents, 50.8% (n = 99) routinely conduct a standardised screening, a multi consistency test in 34.9% (n = 68) and a water swallowing test in 15.9% (n = 31). However, 42.1% (n = 82) of the nurses noted that they are waiting for the specialist (Speech & Language Therapist or an expert in the field of dysphagia) before delivering any oral intake. Out of 195 participants, 5.1% (n = 10) nurses used an unvalidated screening method and 2.1% (n = 4) participants were excluded due to inability to specify the screening method. None reported ‘No screening’. (Flowchart Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart: Categorization and distribution of questionnaire responses by nurses' main workplaces.

4.1. Medication administration based on screening methods

The two groups who used a standardised assessment (MCT + WST) were asked if they provide medications to patients prior to a screening test. According to the survey, 80.8% of the respondents reported that they had never given medication before a dysphagia screening assessment.

Participants were asked how they manage the administration of solid dosage forms if either the screening test was suspicious (Group WST + MCT) or the clinical impression of the patient gave concern about a potential dysphagia or aspiration risk (Group US). The group ‘Waiting for the specialist’ was asked how they managed the situation with medication intake until the expert came. Above all groups, not a single nurse would give a patient with suspected acute dysphagia solid oral medication. However, 32.2% (n = 46) of nurses indicated delivering modified medication (crushed or divided). After grouping the results, the percentages were 26.8% for WS, 40% for US, 41.9% for WST, and 43.6% for MCT (s. Figure 2). In contrast, a non‐oral route (other dosage forms, paused, nasogastric tube) was preferred by an overwhelming majority. The treatment with ‘other dosage forms’ was the most mentioned non‐oral route above the four groups (75.0%–93.6%). (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Non‐oral and oral medication application after acute stroke based on specific dysphagia evaluation methods (Water swallowing test group, multi consistency test group, unvalidated screening group and waiting for the specialist group); NGT, Nasogastric tube (multiple responses were possible) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.2. GUSS‐group

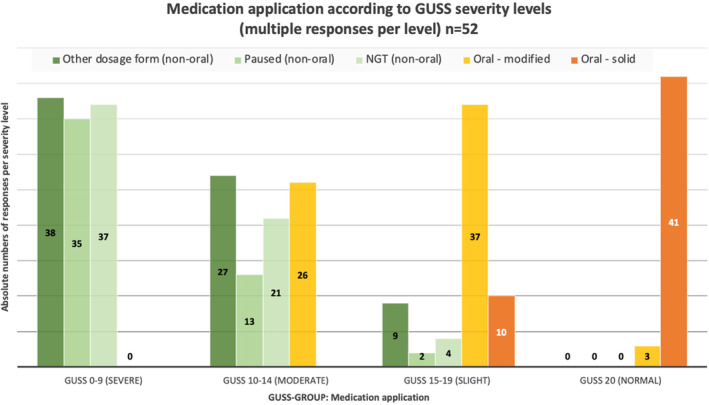

A separate analysis was conducted for the 52 nurses who reported using the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS). The aim was to obtain further information on medication management in relation to dysphagia severity according to GUSS evaluation. As shown in Figure 3, no medications are given orally in patients with severe dysphagia (GUSS 0–9 points), but they are more likely to be modified in moderate to mild dysphagia. Only 10 have pointed out that they give solid drugs to mildly swallowing impaired stroke patients. (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Non‐oral and oral medication application according to the severity levels of the Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS); NGT, nasogastric tube. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.3. Responsibility for drug administration

According to the participating nurses, physicians choose non‐oral medication more frequently, whereas the decision of the method of oral medication intake seems to be more often made by nurses or SLTs. (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Decision on non‐oral and oral administration of medications by occupational group. SLT, Speech and Language Therapist. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.4. Accompanying boluses for medication administration

Nurses were asked how they usually administer medications to dysphagic patients. Figure 5 shows that the most used accompanied textures for the delivery of whole tablets and capsules, as well as modified medications, are semisolid textures, followed by water. (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Most frequently used types of oral medication administration regarding accompanying textures in patients with dysphagia. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In addition, participants were asked to indicate their preferred bolus type for delivering solid or crushed pills. The most mentioned accompanying boluses were apple sauce, followed by yoghurt and thickened water (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Most commonly used accompanying boluses for medication delivery in patients with stroke‐induced dysphagia.

| Accompanying boluses used for medication delivery (multiple responses) n = 176 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | |||

| N | Percentage | Percentage of cases | |

| Accompanying boluses a | |||

| Apple sauce | 124 | 19.0% | 70.5% |

| Yoghurt | 102 | 15.6% | 58.0% |

| Thickened water | 90 | 13.8% | 51.1% |

| Jelly‐like textures | 86 | 13.2% | 48.9% |

| Pudding | 86 | 13.2% | 48.9% |

| Thickened liquids | 71 | 10.9% | 40.3% |

| Mixed into meals | 53 | 8.1% | 30.1% |

| Baby food | 32 | 4.9% | 18.2% |

| Others | 9 | 1.4% | 5.1% |

| Total | 653 | 100.0% | 371.0% |

Dichotomy group tabulated at value 1.

4.5. Self‐assessment of nurses

The last part of the survey referred to the nurses' knowledge, self‐assessment, and self‐responsible actions. When asked whether they would decide to modify medications for safety reasons prior to administration, 70.2% of the respondents stated they do this always, often, or sometimes. (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Frequency of autonomous decision‐making by stroke nurses in relation to changing solid medication in patients with dysphagia. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The nurses provided self‐assessed responses to three questions regarding confidence and knowledge with regard to medication administration. Referring to the first question, the majority (59.0%) of nurses feel ‘fairly confident’ in everyday clinical practice when administering oral medication to patients with swallowing disorders. Second, 52.3% estimated their current knowledge regarding the permissibility of modifying solid medicines as ‘good’. In contrast, 66.1% in the third response stated that they require more information about medication administration in this patient population.

5. DISCUSSION

This research specifically targets stroke nurses due to their expert understanding of the complex patient group with post‐stroke dysphagia. The current literature primarily investigates medication administration in general with nurses working on wards with patients having diverse medical conditions. This study shows that one in two stroke nurses uses standardised dysphagia screenings in patients who are admitted to the stroke unit. Interestingly, the other half of nurses are waiting for the specialist for dysphagia evaluation. The stroke guidelines recommend conducting a screening as soon as possible after admission or before oral intake, including medication intake (Dziewas et al., 2021). Most stroke units have a high availability of healthcare professionals, even on weekends. This could explain why a large proportion of nurses opt to wait for a specialist instead of performing a screening independently.

The initial objective of this project was to describe how nurses decide on the medication application after acute stroke. The most important result was that nurses avoid administering unaltered SMs in patients with suspected or confirmed dysphagia. However, up to 43% would administer modified medications, and most preferred a non‐oral route. These results are in accord with recent studies indicating that patients with dysphagia obtain altered medication more often than solid ones (Blaszczyk et al., 2023). However, the number of nurses who reported altering medications in this investigation is much lower than the percentage observed by previous studies, where up to 88% of nurses reported modifying SM before administration (Daibes et al., 2023; Masilamoney & Dowse, 2018). An implication of this finding is the possibility that intensive care management more likely allows a non‐oral application of medications than for patients in general wards or nursing homes. It is somewhat surprising that 26.8% of nurses, while waiting for the specialist, and 19.2% using a screening method, provide modified medications to the patients without an assessment. In contrast, over 80% of those using a screening test would not administer SM until after the evaluation.

Consistent with the literature, this research found that crushed as well as divided and SMs are more often delivered with semisolid textures than with water. This could be due to the fact that more patients with acute dysphagia initially experience problems with fluids and mixed consistencies rather than semisolid textures (Francesco et al., 2022).

The most mentioned type of bolus, which is regularly used, is apple sauce, followed by yoghurt and thickened water. Some research has shown that applesauce and orange juice, as well as food thickeners, can greatly alter the absorption and bioavailability of some medications (Cichero, 2013; Jackson & Naunton, 2017; Moses, 2020; Yin et al., 2011). These results provide further support for the hypothesis that also the type of bolus is crucial for a safe and appropriate SM administration in patients with dysphagia and must be considered.

The second objective of this study was to identify whether screening methods, especially the multi consistency screening GUSS, can influence the nurses' decision on medication administration. Most striking was that patients who are severely impaired in the GUSS screening would neither receive modified nor whole medications orally. This differs from To et al. (2013), who found that almost 10% of the respondents would give oral medication to a nil‐by‐mouth patient after a stroke (To et al., 2013). Ten nurses who used GUSS reported administering oral SMs in patients with slight dysphagia. This suggests that a more detailed examination of swallowing using a multi consistency test can lead to a more sophisticated adjustment of medication administration.

Another intriguing discovery relates to the issue of which professional determines the suitable method for administering medication. Nurses and SLTs were found to be the professionals most likely deciding on the applicable oral medication administration method. It is noteworthy that pharmacists are seldom engaged in the process of medication management in patients with dysphagia. The lack of pharmacist involvement could potentially lead to suboptimal outcomes and adverse events. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop and implement strategies that promote greater collaboration between pharmacists and other healthcare professionals to optimise the care of dysphagia patients. Studies suggest that patients may benefit from an interdisciplinary exchange to develop a person‐centred, safe and appropriate SM administration (Blaszczyk et al., 2023; O'Hara, 2015).

Nevertheless, overall nurses seem confident in their everyday clinical practice. The majority would decide autonomously to modify medications for safety reasons prior to administration. This result matches those observed in earlier studies (Mc Gillicuddy, Kelly, et al., 2017). One unanticipated result was that more than 50% of nurses indicated feeling ‘fairly confident’ in everyday clinical practice and that they have ‘good’ knowledge regarding the alteration of SMs. This finding contradicts the reported need for further education by 66.1%, aligning with current research (Mc Gillicuddy, Kelly, et al., 2017).

5.1. Limitations

The study utilised convenience and snowball recruiting methods, which may have resulted in a sample that is not fully representative of the intended population. It is also possible that the survey results were confounded by the fact that multiple nurses per stroke unit participated. The cross‐sectional design of this study did not enable any analysis of causal relationships, merely a description of how nurses currently deal with dysphagic patients in the first days after stroke in the light of medication intake. It is worth noting that some respondents did not answer every question, resulting in varying response totals. This could lead to difficulties in interpretation.

6. CONCLUSION

The aim of the present research was to examine the medication management of nurses in acute stroke care and how dysphagia screening methods impact their decisions. The study showed that a non‐oral route of medication application is preferred in the acute stage of stroke. The most obvious finding to emerge from this study is that nurses avoid the administration of whole SMs in patients where a dysphagia screening was suspicious, leading to a higher likelihood of administering altered SM.

A more specific estimation of SM intake was indicated through the usage of GUSS, where the severity levels guided the nurse's decision. This investigation has also shown that a considerable percentage (20%–26.8%) of nurses provide oral medication prior to a screening test or a specialist consultation.

The findings suggest that in order to optimise oral medication modification practices, the needs of individual patients should be routinely and systematically assessed, and decision‐making should be supported by evidence‐based recommendations with multidisciplinary input.

Up to the knowledge of the authors, the present study has been one of the first attempts to thoroughly examine the handling of oral medication intake in stroke‐induced dysphagia from the nurses' perspective.

Further research is needed to evaluate the ability to swallow SMs in acute stroke patients to avoid unnecessary modifications of solid oral dosage forms. It is also required to establish standard operating procedures on stroke units which focus precisely on dysphagia management including medication intake.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

The study addresses the lack of evidence‐based guidance to manage SM intake in patients after acute stroke with dysphagia. A safe medication administration is a crucial responsibility for nurses, which depends on their individual discretion and experience. In this study, none of the respondents would give whole SMs orally to patients with acute dysphagia. Additionally, up to 43% indicated to alter SMs in patients who showed signs of dysphagia or aspiration. Both measures are presumably based on empirical and traditional knowledge since there is a lack of systematic, evidenced‐based research on this matter. This indicates that nurses are well aware of the dangers associated with swallowing disorders in stroke patients. Apple sauce and yoghurt are the most frequently used boluses with which SM are orally delivered. Without multidisciplinary coordination (e.g. pharmacist), the application of these kinds of food in combination with specific medications can lead to medication errors and cause harm to patients. This research should have an impact on all healthcare providers, including advanced practice nurses (ANPs) working with dysphagic patients in stroke units. Medication delivery is an underrepresented and often neglected part of dysphagia management and should be considered in all patients with acute dysphagia.

STATISTICS

C, Steffen Schulz and Yvonne Teuschl are the statistician co‐authors of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to appreciate the contribution of NÖ Landesgesundheitsagentur, legal entity of University Hospitals in Lower Austria, for providing the organisational framework to conduct this research. The authors also would like to acknowledge support by Open Access Publishing Fund of Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences, Krems, Austria.

Trapl‐Grundschober, M. , Schulz, S. , Sollereder, S. , Schneider, L. , Teuschl, Y. , & Osterbrink, J. (2025). Oral intake of solid medications in patients with post‐stroke dysphagia. A challenge for nurses? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 34, 872–882. 10.1111/jocn.17081

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Banda, K. J. , Chu, H. , Kang, X. L. , Liu, D. , Pien, L. C. , Jen, H. J. , Hsiao, S. S. , & Chou, K. R. (2022). Prevalence of dysphagia and risk of pneumonia and mortality in acute stroke patients: A meta‐analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 420. 10.1186/s12877-022-02960-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk, A. , Brandt, N. , Ashley, J. , Tuders, N. , Doles, H. , & Stefanacci, R. G. (2023). Crushed tablet Administration for Patients with dysphagia and enteral feeding: Challenges and considerations. Drugs and Aging, 40(10), 895–907. 10.1007/s40266-023-01056-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaden, E. , Burnell, J. , Hives, L. , Dey, P. , Clegg, A. , Lyons, M. W. , Lightbody, C. E. , Hurley, M. A. , Roddam, H. , McInnes, E. , Alexandrov, A. , & Watkins, C. L. (2021). Screening for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10(10), Cd012679. 10.1002/14651858.CD012679.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann, C. , Bihler, M. , Emich, K. , Hidding, U. , Potter‐Nerger, M. , Gerloff, C. , Niessen, A. , Flugel, T. , Koseki, J. C. , Nienstedt, J. C. , & Pflug, C. (2019). Pill swallowing in Parkinson's disease: A prospective study based on flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 62, 51–56. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnaby‐Mann, G. , & Crary, M. (2005). Pill swallowing by adults with dysphagia. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, 131, 970–975. 10.1001/archotol.131.11.970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichero, J. A. Y. (2013). Thickening agents used for dysphagia management: Effect on bioavailability of water, medication and feelings of satiety. Nutrition Journal, 12(1), 54. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonier, P. A.‐c. , Marquis, J. , & Vale, M.‐P. S. (2013). Swallowing difficulties with oral drugs among polypharmacy patients attending community pharmacies. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 1130–1136. 10.1007/s11096-013-9836-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daibes, M. A. , Qedan, R. I. , Al‐Jabi, S. W. , Koni, A. A. , & Zyoud, S. H. (2023). Nurses' knowledge and practice regarding mixing medications with food: A multicenter cross‐sectional study from a developing country. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 42(1), 52. 10.1186/s41043-023-00396-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziewas, R. , Michou, E. , Trapl‐Grundschober, M. , Lal, A. , Arsava, E. M. , Bath, P. M. , Clavé, P. , Glahn, J. , Hamdy, S. , Pownall, S. , Schindler, A. , Walshe, M. , Wirth, R. , Wright, D. , & Verin, E. (2021). European stroke organisation and European Society for Swallowing Disorders guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of post‐stroke dysphagia. European Stroke Journal, 6(3), Lxxxix‐cxv. 10.1177/23969873211039721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin, V. L. (2021). Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990‐2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurology, 20(10), 795–820. 10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00252-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, J. , Go, J. T. , & Schulze, K. S. (2015). Pill properties that cause dysphagia and treatment failure. Current Therapeutic Research, 77, 79–82. 10.1016/j.curtheres.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesco, M. , Nicole, P. , Letizia, S. , Claudia, B. , Daniela, G. , & Antonio, S. (2022). Mixed consistencies in Dysphagic patients: A myth to dispel. Dysphagia, 37(1), 116–124. 10.1007/s00455-021-10255-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. , & Naunton, M. (2017). Optimising medicine administration in patients with swallowing difficulties. Australian Pharmacist. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. , D'Cruz, G. , & Wright, D. (2009). A qualitative study of the problems surrounding medicine administration to patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia, 24(1), 49–56. 10.1007/s00455-008-9170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. , Wright, D. , & Wood, J. (2012). Medication errors in patients with dysphagia. Nursing Times, 108(21), 12–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22774363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. , Ghaffur, A. , Bains, J. , & Hamdy, S. (2016). Acceptability of oral solid medicines in older adults with and without dysphagia: A nested pilot validation questionnaire based observational study. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 512(2), 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique, Y. J. , Lee, D. J. , Islam, F. , Nissen, L. M. , Cichero, J. A. , Stokes, J. R. , & Steadman, K. J. (2014). Crushed tablets: Does the administration of food vehicles and thickened fluids to aid medication swallowing alter drug release? Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences: A Publication of the Canadian Society for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Societe canadienne des sciences pharmaceutiques, 17(2), 207–219. 10.18433/j39w3v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masilamoney, M. , & Dowse, R. (2018). Knowledge and practice of healthcare professionals relating to oral medicine use in swallowing‐impaired patients: A scoping review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 26(3), 199–209. 10.1111/ijpp.12447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Gillicuddy, A. , Crean, A. M. , Kelly, M. , & Sahm, L. (2017). Oral medicine modification for older adults: A qualitative study of nurses. BMJ Open, 7(12), e018151. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Gillicuddy, A. , Kelly, M. , Crean, A. M. , & Sahm, L. J. (2017). The knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of patients and their healthcare professionals around oral dosage form modification: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy: RSAP, 13(4), 717–726. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses, G. (2020). Don't take your medicine with fruit juice. MIMS Matters. https://www.mims.com.au/content/MimsMatters/Geraldine_Moses_Dont_take_your_medicine_with_fruit_juice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nativ‐Zeltzer, N. , Bayoumi, A. , Mandin, V. P. , Kaufman, M. , Seeni, I. , Kuhn, M. A. , & Belafsky, P. C. (2019). Validation of the PILL‐5: A 5‐item patient reported outcome measure for pill dysphagia. Frontiers in Surgery, 6, 43. 10.3389/fsurg.2019.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICEguidline (NG128) . (2019). Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management . https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128/chapter/Recommendations#avoiding‐aspiration‐pneumonia [PubMed]

- O'Hara, M. (2015). Considerations for medication in dysphagic stroke patients. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, W. J. , Rabinstein, A. A. , Ackerson, T. , Adeoye, O. M. , Bambakidis, N. C. , Becker, K. , Biller, J. , Brown, M. , Demaerschalk, B. M. , Hoh, B. , Jauch, E. C. , Kidwell, C. S. , Leslie‐Mazwi, T. M. , Ovbiagele, B. , Scott, P. A. , Sheth, K. N. , Southerland, A. M. , Summers, D. V. , & Tirschwell, D. L. (2019). Guidelines for the early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke, e344–e418. 10.1161/str.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics . (2005). Qualtrics (development company) . In (Version 2022) [Software] https://www.qualtrics.com/

- Schiele, J. T. , Penner, H. , Schneider, H. , Quinzler, R. , Reich, G. , Wezler, N. , Micol, W. , Oster, P. , & Haefeli, W. E. (2015). Swallowing tablets and capsules increases the risk of penetration and aspiration in patients with stroke‐induced dysphagia. Dysphagia, 30(5), 571–582. 10.1007/s00455-015-9639-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To, T. P. , Story, D. A. , Booth, J. , Nielsen, F. , Heland, M. , & Hardidge, A. (2013). Oral medication administration in patients with restrictions on oral intake—A snapshot survey. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 43(3), 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Trapl, M. , Enderle, P. , Nowotny, M. , Teuschl, Y. , Matz, K. , Dachenhausen, A. , & Brainin, M. (2007). Dysphagia bedside screening for acute‐stroke patients: The Gugging swallowing screen. Stroke, 38(11), 2948–2952. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke, T. , Im, S. , Kaiser, C. , Hamacher, C. , Oelenberg, S. , & Dziewas, R. (2017). Aspiration and dysphagia screening in acute stroke–the Gugging swallowing screen revisited. European Journal of Neurology, 24(4), 594–601. 10.1111/ene.13251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, R. , & Dziewas, R. (2019). Dysphagia and pharmacotherapy in older adults. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 22(1), 25–29. 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S. , Taniguchi, H. , Hayashi, H. , Hori, K. , Tsujimura, T. , Nakamura, Y. , Sato, H. , & Inoue, M. (2014). How do tablet properties influence swallowing behaviours? Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 66, 32–39. 10.1111/jphp.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, O. Q. , Rudoltz, M. , Galetic, I. , Filian, J. , Krishna, A. , Zhou, W. , Custodio, J. , Golor, G. , & Schran, H. (2011). Effects of yogurt and applesauce on the oral bioavailability of nilotinib in healthy volunteers. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 51(11), 1580–1586. 10.1177/0091270010384116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1:

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.