Abstract

The deterioration of human health due to unhealthy lifestyle and dietary habits has led to a worldwide increase in various metabolic diseases that significantly affect public health. Diabetes is one of the most serious health problems, is caused by abnormal metabolic processes and is becoming increasingly common. According to World Health Organisation (WHO) reports, a significant proportion of the world's population suffers from these diseases and their incidence continues to rise at an alarming rate. These metabolic disorders are characterised by elevated blood sugar levels, which serve as a warning sign for a variety of other health problems. Factors contributing to these diseases include a high-fat diet, insufficient physical activity, genetic predisposition, lack of exercise and underlying diseases. Diabetes mellitus, a fast-growing chronic metabolic disease, is characterised by insufficient insulin production by the pancreas or the body's inability to use insulin action. Various strategies are recommended by health and nutrition experts to manage this condition, including lifestyle changes, exercise, low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets and intermittent fasting. In cases where these measures prove insufficient, medication may be prescribed. However, the development of multi-drug therapies for metabolic disorders has proven to be an attractive field for pharmacists as they address several diseases simultaneously. Despite the promising effects of multi-drug therapies, the high costs and potential side effects associated with recently developed drugs necessitate alternative approaches. The utilisation of natural bioactive compounds from plant extracts represents a promising high-throughput strategy. This approach utilises network pharmacology and screening methods to identify potential ligands that act as inhibitors for the treatment of complex, interconnected diseases. In the current investigation, we used a molecular docking approach to investigate secondary metabolites from millet as potential multi-target ligands for the treatment of diabetes and obesity.

Keywords: Metabolic diseases, Diabetes, Obesity, Molecular docking, Plant bioactive compounds

Specifications Table

| Subject | Computational biology |

| Specific subject area | Interdisciplinary field includes organic chemistry, biochemistry, and biology. Drug design and discovery from plant sources. |

| Type of data | Raw and Analysed data including Figures and Tables |

| Data collection | Bioactive compounds present in seed extract of millet were analysed using GC–MS and used as a Ligand Ligand based molecular docking bind against target protein using YASARA software version and visualized by Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer 2020 |

| Data source location | Institute: Department of Botany, Bioinformatics, and Climate Change Impacts Management, School of Sciences, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, City/Town/Region: Ahemdabad, Gujarat Country: India |

| Data accessibility | Repository name: Dataset for millet derived compound fight against diabietic protein alpha-amylase and human maltase gluco‑amylase Data identification number: 10.17632/5nnsfvzz3m.1 Direct URL to data https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5nnsfvzz3m/1 |

| Related research article | Lakhani, K. G., Hamid R, Prajapati P, Patel S, Dwivedi A. and Suthar KP (2024) From Millets to Medicine: ADMET Insights into Diabetes Management with P. sumatrense Compounds. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 61: 103,396. 10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103396. [1] |

1. Value of the Data

-

•

This dataset provides insight of metabolites present in grains millet identified by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectroscopy (GC–MS) act as potent anti-diabetic agent by inhibiting two important enzymes such as alpha-amylase (2QMK) and maltase gluco‑amylase (2QMJ).

-

•

This screening process provides valuable insights into the active natural compounds contained in millet extracts that can influence certain biochemical metabolic pathways and thus contribute to the control and inhibition of metabolic disorders such as diabetes.

-

•

In addition, computational biologists and pharmaceutical scientists can use this information as a basis for virtual analyses aimed at developing new synthetic analogues with reduced side effects and improved bioactivity against these targets.

-

•

This In silico studies serve as an invaluable resource, empowering experimental researchers by seamlessly bridging computational insights with experimental validation.

-

•

By expediting the identification of promising compounds and elucidating their interactions with anti-diabietic targets, these studies substantially accelerate the research timeline, thereby revolutionizing and optimizing the drug discovery pipeline.

-

•

Although the exact mechanisms of action and identification of key ingredients in herbal remedies and dietary supplements that facilitate the control of glucose metabolism are still largely unexplored, the dataset enables the identification of novel drugs for diabetes.

-

•

The binding interactions of little millet derived compounds with two different diabetes-related target proteins facilitate the effective utilisation of this data. This in turn provides important information to drive organic synthesis and the search for analogue pairs in the context of virtual drug design.

2. Background

Diabetes is a chronic, hyperglycaemic disease that poses a major public health challenge and is characterised by persistently elevated blood glucose levels [2]. The pancreatic islet cells, particularly the beta cells within them, are often damaged in diabetes, leading to resistance or impaired insulin secretion, which in turn triggers a hyperglycaemic state [3]. In underdeveloped countries with inadequate access to treatment, diabetes is increasing at an alarming rate. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) predicts that the number of diabetes cases will rise to 693 million by 2045, making it a potentially fatal chronic disease. There are many medications available to control blood sugar levels that do not completely cure diabetes, but focus on controlling or adjusting insulin secretion. Long-term use of therapeutic diabetes medications is often associated with various adverse effects and suboptimal patient compliance [4].

Globally, the increase in diabetes cases can be attributed to changes in dietary habits, particularly the increased consumption of street or packaged foods that are high in saturated fats and sugars but low in essential nutrients [5]. Effective diabetes management relies heavily on lifestyle therapy, which emphasises regular exercise, weight control and the consumption of nutrient-rich foods that support the gradual release of sugars [6]. Meals that are high in fibre and unsaturated fatty acids and have a low glycaemic index are particularly beneficial for controlling diabetes as they help to reduce the rate of sugar absorption into the bloodstream.

Millet, an ancient group of grains, has established itself as a nutrient-rich alternative to staple foods such as rice and wheat. With their nutrient-rich profile, including higher levels of protein, fibre and essential minerals, millets outperform many conventional grains when it comes to meeting nutritional needs and treating various lifestyle-related diseases [7]. Little millets, a group of minor millets often referred to as “nutra-cereals',” are widely consumed by the population in the tribal areas of developing countries in Africa and Asia. The declaration of 2023 as the International Year of Millets by the United Nations has drawn attention to the potential of underutilised crops like little millet to address global challenges [8,9]. This grain is a rich source of various phytochemical compounds, including polyunsaturated fatty acids, flavonoids, organic acids and phenolic compounds [10]. Regular consumption of little millets is associated with the treatment of various diseases such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases [1]. Little Millet, have unique interactions with alpha-amylase and maltase-glucoamylase due to their composition. Their role in modulating these enzymes can influence carbohydrate digestion and blood sugar control, making them beneficial for managing diabetes. This data description presents the bioactive compounds identified in the grains of little millets that act as ligands to inhibit the activity of the target proteins α-amylase and human maltase-glucoamylase and thus contribute to the treatment of metabolic disorders such as diabetes.

3. Data Description

Alpha-amylases and maltase gluco‑amylase are important digestive enzymes that control glucose levels in the treatment of diabetes by lowering postprandial hyperglycaemia (PPHG) levels in animals and humans. To maintain metabolic functions and digestion in the body, potent inhibitors of alpha-amylase and maltase‑gluco-amylase need to be identified to prevent an increase in blood sugar levels due to slow release of glucose due to slow digestion [11]. Pancreatic α-amylase and maltase glucoamylase inhibitors, often referred to as potent starch or carbohydrate blockers, are considered an effective intervention to mitigate hyperglycaemia by curbing the influx of glucose into the bloodstream by attenuating the hydrolysis and absorption of starch from food [12]. In carbohydrate metabolism, these two enzymes are involved in a stepwise process in which maltose is formed from polysaccharide molecules by hydrolysis, which is facilitated by alpha-amylase [13] Through the activity of maltase, glucoamylase is an exo-type enzyme that hydrolyses polymeric carbohydrates by facilitating their subsequent absorption through hydrolysis of complex carbohydrates. The pharmaceutical industry offers a plethora of antidiabetic drugs. However, excessive inhibition of blood glucose-lowering enzymes by these agents can lead to gastrointestinal complications, including diarrhoea [14]. There are many home remedies to control blood glucose levels, which are very popular among patients. However, many patients avoid their consumption due to their taste and unpleasant odour.

Millets are nutrient-rich grains known for their richness in bioactive compounds such as alkaloids, phenols and flavonoids. These metabolites show remarkable efficacy in regulating blood sugar levels and reducing the risks associated with prediabetes. Despite their nutritional and therapeutic potential, the use of small millets, particularly small millets, is still limited and often considered a pseudo-cereal. The discovery of the anti-diabetic properties of small millets increases their value, especially in the development of functional millet-based foods. As these grains can be easily integrated into the daily diet and do not require special preparation, they are a good choice for health-conscious consumers. This study aims to investigate the inhibitory effect of secondary metabolites in millet grains on alpha-amylase and human metabolism to scientifically substantiate their role in combating diabetes and to support millet producers.

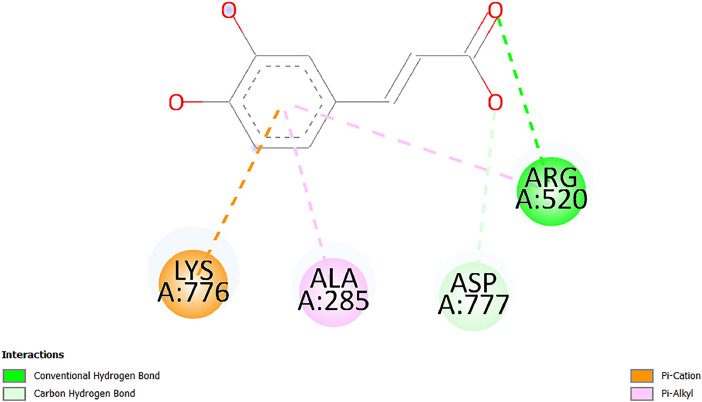

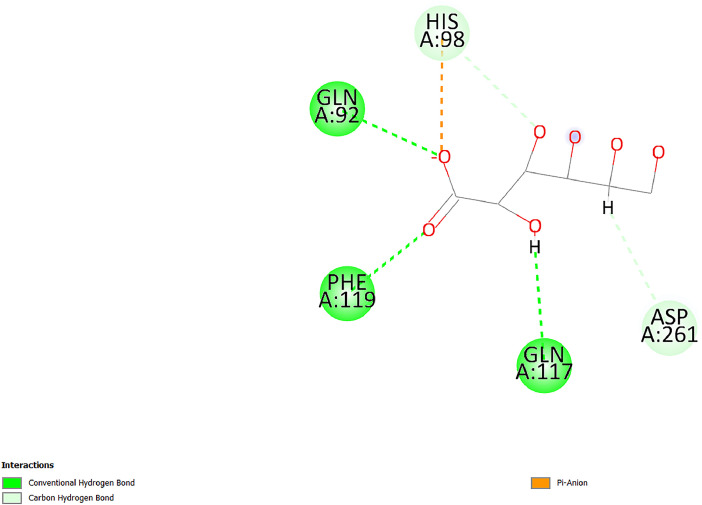

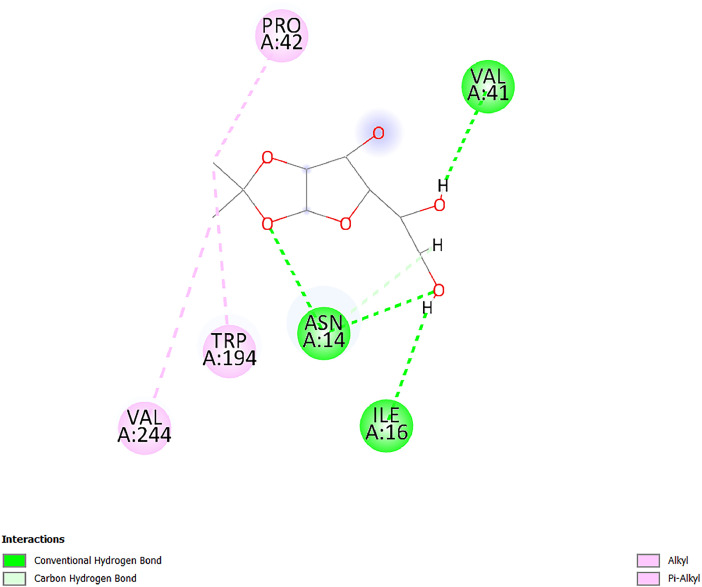

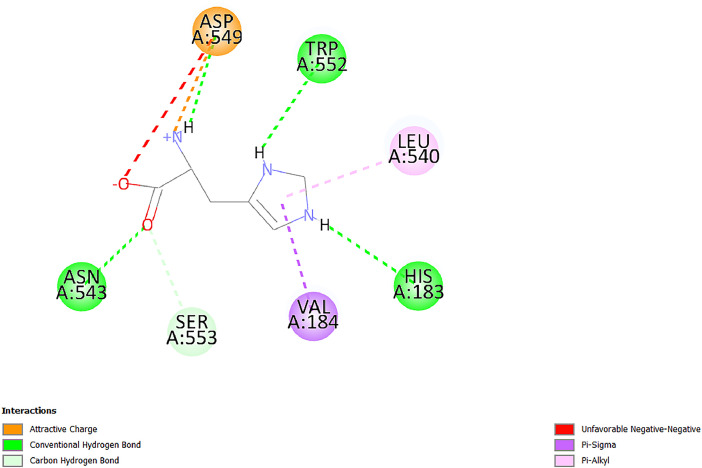

Tables 1 and 2 present the binding free energy data obtained from docking experiments investigating the interactions of bioactive compounds from millet with the proteins α-amylase and human maltase-glucoamylase, respectively. These proteins are important in the context of diabetes-related metabolic disorders. The interactions between the ligands and the active sites of the target proteins are elucidated by the amino acid residues listed in Tables 3 and 4 (see suppl. Table 1 and suppl. Table 2). The result of molecular docking of top five compounds for both proteins by involvement of amino acids illustrated in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21, Fig. 22, Fig. 23, Fig. 24, Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27, Fig. 28, Fig. 29, Fig. 30 for 2QMK and Fig. 31, Fig. 32, Fig. 33, Fig. 34, Fig. 35, Fig. 36, Fig. 37, Fig. 38, Fig. 39, Fig. 40, Fig. 41, Fig. 42, Fig. 43, Fig. 44, Fig. 45, Fig. 46, Fig. 47, Fig. 48, Fig. 49, Fig. 50, Fig. 51, Fig. 52, Fig. 53, Fig. 54, Fig. 55, Fig. 56, Fig. 57, Fig. 58, Fig. 59, Fig. 60 for 2QMJ protein.

Table 1.

The calculated binding energy of co-crystal ligand and natural compounds derived from Little Millet with Alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK) using YASARA structure.

| Ligand | Binding energy [kcal/mol] |

Dissociation constant [pM] | Pubchem Id | Efficiency [kcal/(mol*Atom)] |

Con. Surf [A^2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobolin | 8.0090 | 1,346,868.3750 | 54,688,606 | 3814 | 228.91 |

| Xanthosine | 7.6420 | 2,502,302.0000 | 64,959 | 3821 | 217.72 |

| Arbutin | 7.2870 | 4,555,732.0000 | 440,936 | 3835 | 242.47 |

| Sinapic acid | 7.2440 | 4,898,663.5000 | 637,775 | 4527 | 224.22 |

| Maltose | 7.0630 | 6,648,939.0000 | 6255 | 3071 | 245.87 |

| L-Tryptophan | 6.8230 | 9,969,530.0000 | 6305 | 4549 | 229.05 |

| Caffeic acid | 6.8020 | 10,329,229.0000 | 689,043 | 5232 | 174.32 |

| Pyrido[3,4-d] imidazole | 6.7150 | 11,962,990.0000 | 541,512 | 4477 | 177.65 |

| Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid | 6.3420 | 22,451,862.0000 | 21,145,257 | 2883 | 344.20 |

| L-Tyrosine | 6.3090 | 23,737,866.0000 | 6057 | 4853 | 211.59 |

| 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol | 6.1690 | 30,065,128.0000 | 183,823 | 4745 | 192.98 |

| D-Fructopyranose | 6.1210 | 32,602,246.0000 | 2,723,872 | 5101 | 141.20 |

| 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid | 6.1150 | 32,934,082.0000 | 193,792 | 4077 | 212.79 |

| Gluconic acid | 6.0640 | 35,894,596.0000 | 10,690 | 4665 | 157.06 |

| 2, 5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine | 6.0430 | 37,189,664.0000 | 27,402 | 3777 | 251.56 |

| Gulonic acid | 6.0360 | 37,631,656.0000 | 152,304 | 4311 | 183.82 |

| 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-d- glucofuranose | 6.0320 | 37,886,576.0000 | 87,704 | 4021 | 198.08 |

| Phenylphrine | 6.0240 | 38,401,612.0000 | 6041 | 5020 | 185.62 |

| p-hydroxynorephedrine | 5.9890 | 40,738,476.0000 | 11,099 | 4991 | 176.04 |

| Synephrine | 5.9120 | 46,392,368.0000 | 7172 | 4927 | 185.58 |

| Mannoic acid | 5.8590 | 50,733,644.0000 | 3,246,006 | 4507 | 162.35 |

| 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol | 5.8570 | 50,905,192.0000 | 167,995 | 4881 | 217.63 |

| I-Guanidinosuccinimide | 5.8130 | 54,829,528.0000 | 541,546 | 5813 | 147.59 |

| Cathine | 5.7270 | 63,394,756.0000 | 441,457 | 5206 | 142.79 |

| L-histidine | 5.6290 | 74,797,712.0000 | 6274 | 5117 | 196.36 |

| 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester |

5.4370 | 211,554,512.0000 | 543,579 | 3198 | 263.54 |

| Heptanedioic acid | 5.4230 | 105,898,128.0000 | 385 | 4930 | 177.57 |

| 2-Butenedioic acid | 5.3410 | 12,167,224.0000 | 44,972 | 6676 | 114.06 |

| 10-Octadecenoic acid | 5.3140 | 127,287,672.0000 | 445,639 | 2657 | 170.37 |

| L- Alanine ethylamide, (S) | 4.5230 | 483,723,328.0000 | 7,128,993 | 5654 | 151.43 |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid | 4.1950 | 841,442,112.0000 | 5,282,768 | 1907 | 284.23 |

Table 2.

The calculated binding energy of co-crystal ligand and natural compounds derived from Little Millet with Human Maltase Gluco-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ) using YASARA structure.

| Human Maltase Glucoamylase | Binding energy [kcal/mol] |

Dissociation constant [pM] | Pubchem id | Efficiency [kcal/(mol*Atom)] |

Con. Surf [A^2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobolin | 6.7980 | 10,399,200.0000 | 54,688,606 | 3237 | 238.31 |

| Xanthosine | 6.7940 | 10,469,645.0000 | 64,959 | 3397 | 192.37 |

| Arbutin | 6.8410 | 9,671,203.0000 | 440,936 | 3601 | 216.81 |

| Sinapic acid | 6.8150 | 10,105,057.0000 | 637,775 | 4259 | 255.18 |

| Caffeic acid | 6.6320 | 13,761,936.0000 | 689,043 | 5102 | 203.76 |

| Tyrosine | 6.4910 | 17,459,584.0000 | 6057 | 4993 | 202.60 |

| Maltose | 6.4390 | 19,061,208.0000 | 6255 | 2800 | 242.82 |

| 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol | 6.3740 | 1,271,398.0000 | 183,823 | 4903 | 221.19 |

| p-hydroxynorephedrine | 6.3140 | 23,538,384.0000 | 11,099 | 5262 | 198.00 |

| Cathine | 6.2080 | 28,149,822.0000 | 441,457 | 5644 | 210.68 |

| L-Histidine | 6.1330 | 31,948,568.0000 | 6274 | 5575 | 202.80 |

| Gluconic acid | 6.1320 | 32,002,536.0000 | 10,690 | 4717 | 153.44 |

| L-Tryptophan | 6.0990 | 33,835,588.0000 | 6305 | 4066 | 224.03 |

| L-phenylephrine | 6.0760 | 35,174,908.0000 | 6041 | 5063 | 194.01 |

| Synephrine | 6.0570 | 36,321,196.0000 | 7172 | 5048 | 188.81 |

| Pyrido[3,4-d] imidazole, 1,6-dicarboxylic acid | 5.9910 | 40,601,192.0000 | 541,512 | 3994 | 177.39 |

| 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine | 5.8900 | 48,147,392.0000 | 27,402 | 3681 | 242.07 |

| 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-d- glucofuranose | 5.7480 | 61,187,136.0000 | 87,704 | 3832 | 173.91 |

| Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid | 5.6080 | 341,086,112.0000 | 21,145,257 | 2150 | 266.44 |

| 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid | 5.4560 | 100,161,072.0000 | 193,792 | 3637 | 202.09 |

| I-Guanidinosuccinimide | 5.4440 | 102,210,400.0000 | 541,546 | 5444 | 170.97 |

| D-Fructopyranose | 5.3570 | 118,376,896.0000 | 2,723,872 | 4464 | 151.02 |

| Gulonic acid | 5.3120 | 127,718,080.0000 | 152,304 | 4086 | 163.09 |

| 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol | 5.1960 | 155,339,360.0000 | 167,995 | 4330 | 203.73 |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid | 5.0260 | 206,963,216.0000 | 5,282,768 | 2285 | 277.81 |

| Mannoic acid | 4.9290 | 243,778,336.0000 | 3,246,006 | 3792 | 158.91 |

| 2-Butenedioic acid | 4.9140 | 250,028,912.0000 | 444,972 | 6143 | 130.29 |

| Heptanedioic acid | 4.7170 | 348,652,800.0000 | 385 | 4288 | 186.80 |

| L- Alanine ethylamide (S) |

4.3040 | 700,045,312.0000 | 7,128,993 | 5380 | 173.21 |

| 10-Octadecenoic acid | 4.2210 | 805,315,328.0000 | 445,639 | 2111 | 269.31 |

| 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester |

3.5670 | 2,428,590,848.0000 | 543,579 | 1783 | 241.97 |

Table 3.

Interacting amino acids of the Alpha-amylase (2QMK) with the ligands derived from Little Millet.

| Ligands | Hydrogen Bonds | Alkyl and Pi bonds | Attractive Charges | Unfavourable bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobolin |

Conventional HB: 6; Arg252(2.47), Gln8(1.18), Asp402(2.09), Arg421(2.73), Gly403(2.46), Pro332(2.45) |

Alkyl: 1; Arg398(3.94) | Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Gln8(1.18) | |

| Xanthosine |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg10(2.43), Gln7(2.13) Carbon HB: 6; Pro4(2.56), Pro4(2.97), Gln8(2.71). Thr11(2.87), Gly334(2.33), Pro332(3.08) |

Pi-alkyl: 2; Pro4(4.84), Pro4(4.86) Amide Pi stacked: 1; Arg10(4.83) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg398(2.37) | |

| Arbutin |

Conventional HB: 3; Gly403(2.23); Gln7(2.83); Gln8(2.41) Carbon Hydrogen Bond: 2; Asp402(2.13); Gly334(2.12) |

Pi-Alkyl: 1; Pro4(4.09) | ||

| Sinapic acid |

Conventional HB: 5; Thr6(2.53), Arg10(2.82), Arg252(2.68), Arg398(3.06), Ser289(3.07) Carbon Hydrogen Bond: 2; Gln8(2.60), Ser289(2.90) |

Unfavourable Negative-Negative:1; Asp402(5.26) | ||

| Maltose |

Conventional HB: 6; Thr6(2.71), Thr6(2.50), Gln7(2.24), Ser289(2.43), Arg10(2.96), Arg398(2.54) Carbon HB: 4; Gln8(2.75), Gly334(2.36), Pro4(2.60), Pro332(2.46) |

Unfavourable Acceptor-Acceptor: 1; Pro332(2.93) |

||

| L-Tryptophan |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg195(2.54), Asn298(2.50) Carbon Hydrogen Bond: 2; Glu233(2.78), Asp300(2.61) |

Pi-Pi stacked: 2; Tyr62(5.00), Tyr62(3.89) |

Attractive Charge: 2; Arg195(4.80), Glu233(4.27) Salt-Bridge Attractive Charge: 2; Asp300(2.90), Asp300(2.16) |

|

| Caffeic acid |

Conventional HB:2; Arg252(2.76), Arg421(2.35) Carbon Hydrogen Bond: 2; Pro332(2.70), Asp402(2.26) |

|||

| Pyrido[3,4-d]imidazole |

Conventional HB:2; Arg252(2.44), Gly334(2.57), Carbon Hydrogen Bond: 2; Pro332(3.03), Thr11(2.56) |

Pi-alkyl: 1; Arg398(5.38) Pi cation: 1; Arg398(4.32) Pi-Anion: 1; Asp402(4.14) |

Attractive Charge: 1; Asp252(4.57), Asp252(4.60), Arg398(5.29) |

|

| Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid |

Alkyl: 4 Ala198(4.35), Ile235(5.09), Leu162(4.02), Leu165(5.23), Pi alkyl: 2 Tyr62(5.42), Tyr62(4.00) |

|||

| L-Tyrosine |

Conventional HB: 2 Arg195(2.64), Asn298(2.76) |

Pi-Pi stacked: 1; Tyr62(4.43) |

Attractive charge: 3 Arg195(4.57), Asp300(3.18), Glu233(4.48) Salt-Bridge:1 Asp300(2.56) |

|

| 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol |

Conventional HB: 2; Gln8(2.36), Thr11(2.69) Halogen: 1; Gly334(3.56) Carbon HB: 4; Phe335(2.98), Phe335(2.55), Pro332(3.03), Gly334(2.90) |

Pi alkyl: 1; Pro4(5.33) Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Phe335(4.95) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg398(1.11) Unfavourable Acceptor-Acceptor: 1; Gly334(2.91) |

|

| D-Fructopyranose |

Conventional HB: 3; Arg398(2.49), Arg421(2.19), Pro332(2.45) Carbon HB: 2; Phe335(2.42), Thr11(2.85) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1 Arg398(0.95) |

||

| 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg398(2.69), Gln8(1.84) Carbon HB: 2; Asp402(2.88), Thr11(2.60) |

Alkyl: 1; Arg398(4.49), |

Unfavorable Negative-Negative: 1 Asp402(3.58) |

|

| Gluconic acid |

Conventional HB: 8; Arg398(1.91), Arg398(2.73), Arg421(2.86); Pro332(2.41); Gly334(3.03); Pro332(2.60); Asp402(2.52); Arg421(1.75) |

Attractive Charge: 1; Arg252(4.54) | Unfavourable donor-donor: 1; Arg421(2.07), | |

| 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine |

Carbon HB: 2; Arg10(3.02), Ser289(2.38) |

Alkyl: 1; Pro4(4.32), Pi-Alkyl:1; Phe335(5.06) |

Salt-Bridge Attractive Charge: 1; Asp402(2.04) |

Unfavourable Positive- Positive: 1; Arg421(4.87) |

| Gulonic acid |

Conventional HB: 1; Asp402(2.80) Carbon HB: 1; Pro332(2.31) |

Salt bridge: 1; Arg252(2.78) |

Unfavourable donor-donor: 2; Arg421(2.07), Arg421(2.07) Unfavourable Acceptor – Acceptor: 1; Gly334(2.73) |

|

| 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-d- glucofuranose |

Conventional HB: 4; Arg398(2.84), Pro332(2.63), Gly334(2.61), Gly403(2.85) Carbon HB: 2; Thr11(2.68), Ser289(2.54) |

Alkyl: 2; Arg398(4.25), Pro332(5.24) |

||

| Phenylphrine |

Conventional HB: 3; Arg398(2.40), Asp402(2.44), Gly334(2.20) Carbon HB: 3; Arg10(2.59), Gln8(2.71), Thr6(2.96) |

Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Phe335(4.76) |

||

| p-hydroxynorephedrine |

Conventional HB: 4; Arg398(1.86), Pro332(2.76); Gly334(2.93); Gly334(2.42) Carbon HB: 1; Thr11(2.90) |

Alkyl: 1; Arg398(4.53) Pi-Alkyl:1; Pro4(5.34) Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Phe335(4.72) |

||

| Synephrine |

Conventional HB: 2; Asp402(2.79), Gln7(2.24) Carbon HB: 3; Arg10(2.34), Gln8(2.73), Thr6(3.04) |

Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Phe335(4.65) |

Attractive charge: 1; Asp402(4.69) |

|

| Mannoic acid |

Conventional HB: 4; Arg398(2.32), Pro332(2.41); Gly334(2.97); Val401(2.16) Carbon HB: 2; Pro332(2.31), Phe335(2.92) |

Attractive charge:2; Arg262(4.66), Arg398(5.10) |

||

| 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol |

Carbon HB:1; Glu233(2.94) |

Alkyl: 1; Leu165(4.53) Pi-Pi stacked: 1; Tyr62(4.26) |

Salt Bridge Attractive Charge: 2; Asp300(2.64), Asp300 (2.34) Attractive Charge: 1; Glu233(4.23) |

|

| I-Guanidinosuccinimide | Conventional HB: 4; Arg303(2.58), Asn301(2.71), Ile312(2.74), Gly309(2.61) | |||

| Cathine |

Conventional HB: 2; Glu484(2.91), Gln390(2.39) Carbon HB: 1; Gln390(2.94) |

Alkyl: 1; Arg389(4.54) Pi-alkyl: 1; Ala318(5.47) Pi-Pi stacked: 1; Trp388(3.80) |

||

| Histidine |

Conventional HB: 3; Asp300(2.44), Asn298(2.72), Arg195(2.57) Carbon HB: 1; Glu233(3.00) |

Pi-Pi stacked: 1; Tyr62(4.17) |

Salt-Bridge Attractive charge: 2; Asp300(2.80), Asp300(2.32), Attractive charge:2; Arg195(4.66), Glu233(2.53) |

|

| 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester |

Conventional HB: 1; Gln390(2.33) Carbon HB: 2; Gln390(2.87), Glu484(2.59) |

Alkyl: 5; Lys322(5.36), Val383(4.79), Arg343(4.78), Val383(4.49), Arg389(4.21) Pi-Alkyl: 7; Phe315(4.85), Trp316(4.30), Trp388(5.20), Trp388(5.38), Trp388(4.09), Trp388(5.04), Trp388(3.83) |

||

| Heptanedioic acid |

Conventional HB: 3; Gln7(2.33), Gln8(2.47), Asp402(2.92) Carbon HB: 1; Asp402(2.49) |

Salt Bridge: 1; Arg398(4.76) Attractive charge: 1 Arg421(2.67) |

||

| 2-Butenedioic acid |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg398(2.58), Arg421(2.51) Carbon HB: 1; Asp402(2.76) Pro332(2.67) |

Attractive charge: 1; Arg398(4.97) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg421(1.64) |

|

| 10-Octadecenoic acid |

Conventional HB: 1; Gln63(2.13) |

Alkyl: 6; Ala198(4.52), Ala198(5.10), Leu162(4.70), Leu165(4.94), Lys200(4.22), Ile235(3.81) Pi-alkyl: 4; Tyr62(4.57), Tyr62(4.70), His201(4.98), His305(4.99) Pi-Anion: 1; Trp59(3.87) |

10-Octadecenoic acid | |

| L- Alanine ethylamide, (S) |

Conventional HB: 6; Ala310(2.94), Asn301(3.07), Ile312(2.32), Gly309(2.12), Arg267(2.88), Arg346(2.68) |

Alkyl: 1; Ala310(4.39) Pi-Alky: 1; Phe348(5.28) |

L- Alanine ethylamide, (S) | |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid |

Conventional HB: 2; Gly403(2.42), Arg421(2.87) Carbon HB: 1; Asp402(2.59) |

Alkyl: 1; Pro4(4.96) Pi-Alkyl: 1; Phe335(5.38) |

Salt Bridge: 1; Arg421(2.32) |

11-Eicosenoic acid |

Table 4.

Interacting amino acids of the Human Maltase Gluco-amylase (2QMJ) with the ligands derived from Little Millet.

| Ligands | Hydrogen Bonds | Alkyl and Pi bonds | Attractive Charges | Unfavourable bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobolin |

Conventional HB: 3; Arg471(1.98), Ser40(2.78), Thr196(2.98) |

Alkyl: 1; Val244(4.11) Pi-Alkyl: 1; Trp194(4.98) |

||

| Xanthosine |

Conventional HB: 2; Asp759(1.97), Glu760(2.69) Carbon HB: 3; Ala764(2.56), Gly731(2.62), Glu760(2.52) |

Pi-alkyl: 1; Lys765(4.78) | Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Val699(1.96) | |

| Arbutin |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg647(2.78), Glu767(2.19) Carbon HB: 2; Asp649(2.56), Pro736(3.01) |

Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Tyr636(4.97) Pi-Anion:1; Glu767(4.00) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg653(1.28) | |

| Sinapic acid |

Conventional HB: 5; Arg252(2.68), Arg10(2.82), Arg398(2.84), Ser289(3.07), Thr6(2.53) |

Attractive charge: 1; Arg520(4.49) |

Unfavourable Negative- Negative: 1; Asp402(5.26) |

|

| Caffeic acid |

Conventional HB: 1; Arg520(2.70) Carbon HB: 1; Asp777(2.88) |

Pi-Alkyl: 3; Ala285(3.43), Arg520(5.11) Pi-Cation: 1; Lys776(4.28) |

||

| Tyrosine |

Conventional HB: 2; Arg647(2.71), Glu767(1.97) Carbon HB: 1; Pro767(2.65) |

Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Tyr636(4.94) Pi-Anion: 1; Glu767(4.05) |

Salt Bridge Attractive Charge: 4; Arg653(2.43), Arg653(1.87), Glu767(2.70), Glu767(2.52) Attractive Charge: 2; Arg647(4.10), Asp649(5.03) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg647(1.80) Unfavourable Acceptor-Acceptor: 1; Ile734() |

| Maltose |

Conventional HB: 6; Ile734(5.63), Arg647(6.41), Asp649(5.27), Glu658(5.02), Glu658(5.38), Tyr733(6.42) Carbon HB: 3; Glu767(3.18), Lys766(3.69) Lys765(5.40) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg653(6.34) | ||

| 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol |

Conventional HB: 3; Arg520(2.54), Arg520(2.34), Arg520(2.03), Carbon HB: 3; Ser521(2.95), Phe535(2.42), Phe535(2.77) |

Pi-Alkyl: 3; Ala285(4.32), Ala537(4.56), Pro287(5.21) Pi-Sulfur: 1; Met567(4.64) |

Unfavourable Positive-Positive: 1; Lys776(5.15) | |

| p-hydroxynorephedrine | Conventional HB: 1; Ile734(2.17), |

Alkyl: Pro676(4.00) Pi-Anion: 1; Glu767(3.85) Pi-Pi T shaped: 1; Tyr636(5.03) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Arg647(1.26) | |

| Cathine |

Conventional HB: 1; Arg520 (2.70) Carbon HB: 1; Asp777(2.88) |

Alkyl: 1; Ala285(3.73) Pi-Alkyl: 3; Arg520 (5.10), Ala285(3.43) Lys776(4.69) Pi-Cation: 1; Lys776(4.22) |

||

| L-Histidine |

Conventional HB: 4; Asn543(4.13), His183(6.20), Trp552(4.46), Asp549(2.98) Carbon HB: 1; Ser553(4.17) |

Pi-alkyl: 1; Leu540(5.60) Pi-sigma:1; Val184(3.85) |

Attractive charge: 1; Asp549(3.75) |

Unfavorable Negative-Negative: 1; Asp549(5.98) |

| Gluconic acid |

Conventional HB: 3; Gln92(2.33), Phe119(2.02), Gln117(2.45) Carbon HB: 1; His98(2.83), Asp261(2.61) |

Pi-Anion: 1; His98(3.41) |

||

| L-Tryptophan | Conventional HB: 1; Arg653(2.27) |

Pi-Alkyl: 2; Pro676(4.43), Pro676(4.86) Pi-Anion: 1; Glu767(3.50) |

Attractive charge: 2; Arg647(2.96), Arg653(4.88) Salt- Bridge Attractive charge: 1; Glu658(3.01) |

|

| L-phenylephrine | Conventional HB: 4; Arg526(2.39), Asp542(2.16), Asp542(2.65), His600(2.36), | Pi-Anion: 1; Asp443(3.84) | ||

| Synephrine |

Conventional HB: 3; Glu767(2.00), Glu767(2.06), Glu767(2.50) |

Pi-Anion: 1; Glu767(3.86) |

||

| Pyrido[3,4-d] imidazole, 1,6-dicarboxylic acid |

Conventional HB: 4; Ser395(2.68), Ser395(2.20), Asp396(2.57), Ser459(2.07) Carbon HB: 1; Cys458(2.84) |

Pi-Alkyl: 1; Leu401(5.46) | ||

| 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine |

Carbon HB: 6; Gly753(2.64), Leu754(2.59), Glu815(2.72), Glu815(2.56), Thr632(2.75), Glu815(4.10) |

Alkyl: 4; Ile755(4.88), Lys817(4.63), Pro740(4.50), Tyr703(4.94) Pi-Anion: 1; Ile755(5.47) |

||

| 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-d- glucofuranose |

Conventional HB: 4; Asn14(2.39), Asn14(2.52), Ile16(2.57), Val41(2.07) Carbon HB: 1; Asn14(2.84) |

Alkyl: 2; Pro42(3.82), Val244(4.93) Pi-Alkyl: 1; Trp194(4.69) |

||

| Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid |

Alkyl: 1; Ala576(4.46) Pi-Alkyl:7; Tyr299(5.12), Tyr299(5.11), Trp406(5.14), Trp406(5.43), Phe575(4.88), Phe575(4.91), Phe575(5.43) |

|||

| 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid |

Conventional HB: 3; Thr737(2.11), Gln739(2.71), Glu815(2.85) Carbon HB: 2; Gln738(2.99), Gly753(2.81) |

Pi-Anion: 1; Glu815(3.23) | ||

| I-Guanidinosuccinimide |

Conventional HB: 3; Phe535(2.28), Arg520(2.03), Ser521(2.87) Carbon HB: 1; Ala536(2.99), |

|||

| D-Fructopyranose |

Conventional HB: 3; Leu752(1.97), Asn814(2.32), Asn814(2.20) Carbon HB: 2; Gln738(2.96), Glu815(3.07) |

|||

| Gulonic acid |

Conventional HB: 6; Glu333(2.74), Arg334(2.35), Asp329(2.72), Asp343(1.80), Glu300(2.45), Gly302(3.06) Carbon HB:2; Gly302(3.06), Glu300(2.81) |

Attractive charge: 1; Arg334(4.69) |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Glu333(1.25) Unfavourable Negative- Negative: 1; Glu333(4.86) Unfavourable Acceptor- Acceptor: 1; Asp343(2.82) |

|

| 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol | Conventional HB: 1; Asp348(2.47) |

Pi-Alkyl: 2; Lys519(5.26), His432(4.50) Pi-Cation: 1; Phe516(4.14) Pi - Pi T shaped: 1; Phe516(4.75) |

Attractive charge: 1; Asp348(4.28) Phe516() |

Unfavourable Donor-Donor: 1; Ser521(2.32) |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid |

Conventional HB: 1; Gln603(2.05) Carbon HB: 1; Gly602(2.72) |

Pi-alkyl: 10; Tyr299(5.00), Tyr299(4.21), Trp406(4.66), Trp406(5.45), Trp406(4.96), Trp406(4.69), Phe450(5.41), Phe450(4.32), Phe450(4.96), Phe575(4.87) |

||

| Mannoic acid |

Conventional HB: 4; Ser456(3.05), Ser395(2.49), Sr459(2.22), Asp485(2.79) Carbon HB: 3; Cys458(2.66), Ser454(2.71), Ser456(2.65) |

Unfavorable Negative-Negative: 1; Asp485(4.56) Unfavorable Acceptor-Acceptor: 1; Ser394(2.82) |

||

| 2- Butendioic acid |

Conventional HB: 2; Phe535(6.41), Ile523(3.68) Carbon HB: 1; Pro287(3.81) |

|||

| Heptanedioic acid |

Conventional HB: 3; Asn14(2.55), Arg254(2.25), Asn14(2.11) Carbon HB: 1; Pro17(2.92) |

Alkyl: 1; Pro42(4.63) Pi-Anion: 1; Trp43(4.89) |

Attractive charge: 2; Arg254(3.97) Arg471(3.18) |

|

| L- Alanine ethylamide (S) |

Conventional HB: 2; Thr821(3.46), Thr821 (3.61) |

Alkyl: 4; Lys762(4.22), Leu758(4.90), Lys762(5.09), Val791(4.94) Pi-alkyl: 3; Trp868(5.22), Trp868(4.94), His870(3.99) |

||

| 10-Octadecenoic acid |

Conventional HB: 2; Trp43(4.84), Ser40(4.14) |

Alkyl: 4; Pro21(4.89), Pro21(5.14), Pro42(4.89), Val244(4.79) Pi-Alkyl: 1; Trp194(5.13) Pi-Sigma: 1; Trp43(2.46) |

||

| 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester |

Alkyl: 1; Leu127(4.80) Pi-alkyl: 3; Tyr91(5.23), Phe65(5.10), Phe65(4.56) |

Fig. 1.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Actinobolin with the alpha-amylase enzyme (PDB ID: 2QMK), illustrating key binding interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and ionic interactions. The figure highlights the specific residues of alpha-amylase involved in the interaction, providing insights into the binding mechanism of Actinobolin and its potential inhibitory effects on enzymatic activity.

Fig. 2.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Xanthosine with the alpha-amylase enzyme (PDB ID: 2QMK), depicting the molecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces. This figure also identifies the active site residues interacting with Xanthosine, emphasizing its role in modulating enzymatic activity.

Fig. 3.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Arbutin with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), showing the interaction landscape, including hydrophobic pockets and polar residues. The visualization provides a clear understanding of Arbutin's binding affinity and specificity towards the enzyme.

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Sinapic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The figure details the types of interactions, including hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds, and their contribution to the binding energy and specificity of Sinapic acid.

Fig. 5.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Maltose with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). This figure highlights the interaction network within the active site, revealing how Maltose aligns with the catalytic residues to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis.

Fig. 6.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L-Tryptophan with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The depiction includes key interactions, such as aromatic stacking and hydrogen bonds, explaining l-Tryptophan's potential inhibitory or modulatory role.

Fig. 7.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Caffeic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), showing the binding interface and highlighting critical residues that stabilize the interaction. This provides insight into the role of Caffeic acid in influencing enzyme function.

Fig. 8.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Pyrido[3,4-d]imidazole, 1,6-dicarboxylic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The figure illustrates the molecular interaction profile, emphasizing ionic bonds and hydrogen bonding networks.

Fig. 9.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The representation focuses on the interaction hotspots within the enzyme's binding pocket, providing insights into Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid's potential as a ligand.

Fig. 10.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L-Tyrosine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The figure highlights specific interactions, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts, that contribute to L-Tyrosine's binding affinity.

Fig. 11.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The interactions depicted include hydrogen bonds and polar contacts, providing insight into its potential enzymatic inhibition.

Fig. 12.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of D-Fructopyranose with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), focusing on the active site interactions that facilitate carbohydrate recognition and hydrolysis.

Fig. 13.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), illustrating the molecular binding landscape and key residues involved in the interaction.

Fig. 14.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Gluconic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The figure highlights the interaction features, including hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions, within the enzyme's active site.

Fig. 15.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The binding interactions depicted highlight the molecular features that may influence enzymatic activity.

Fig. 16.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Gulonic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), focusing on the interaction dynamics and their implications for enzyme-ligand affinity.

Fig. 17.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-D-glucofuranose with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). This figure emphasizes the role of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts in stabilizing the ligand within the binding pocket.

Fig. 18.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Phenylphrine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), illustrating the structural basis for the interaction and its potential effects on enzymatic activity.

Fig. 19.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of p-Hydroxynorephedrine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), showing detailed interaction features, including ionic and hydrogen bonding.

Fig. 20.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Synephrine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). This figure highlights critical binding interactions and their potential role in modulating enzymatic function.

Fig. 21.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Mannoic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), representation focus on active site residues interacting with hydrogen bond and attractive charge, emphasizing its role in modulating enzymatic activity.

Fig. 22.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK), illustrating the structural basis for the interaction and its potential effects on enzymatic activity.

Fig. 23.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Guanidinosuccinimide with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The figure illustrates the molecular interaction profile, emphasizing hydrogen bonding networks.

Fig. 24.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Cathine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK) illustrating key binding interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and ionic interactions, and their contribution to the binding energy and specificity of Cathine.

Fig. 25.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L-histidine with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). This figure highlights the interaction network by hydrogen bonds, alkyl contacts, and electrostatic interactions within the active site, revealing how L-histidine aligns with the catalytic residues to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis.

Fig. 26.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK) showing detailed interaction features, including hydrogen bonding and ionic intereactions.

Fig. 27.

2D interactions of Heptanedioic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK). The binding interactions depicted highlight the molecular features that may influence enzymatic activity.

Fig. 28.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2-Butenedioic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK).

Fig. 29.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 10-Octadecenoic acid with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK).

Fig. 30.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L- Alanine ethylamide, (S) with alpha-amylase (PDB ID: 2QMK).

Fig. 31.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Actinobolin with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 32.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of xanthosine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 33.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Arbutin with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 34.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Sinapic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 35.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Maltose with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 36.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L-Tryptophan with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 37.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Caffeic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 38.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Pyrido[3,4-d]imidazole, 1. 6-dicarboxylic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 39.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Prosta 5,13‑dien-1-oic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ). This figure emphasizes the role of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts in stabilizing the ligand within the binding pocket.

Fig. 40.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L-Tyrosine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ) focusing on the interaction dynamics and their implications for enzyme-ligand affinity.

Fig. 41.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 4-Fluoro-3-[1‑hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl] phenol with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ), illustrating the molecular binding landscape and key residues involved in the interaction.

Fig. 42.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of D-Fructopyranose with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 43.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 3-Ethoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 44.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Gluconic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 45.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 46.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Gulonic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ), focusing on the interaction dynamics and their implications for enzyme-ligand affinity.

Fig. 47.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 1,2 O-Isopropylidene-alpha-D-glucofuranose with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 48.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Phenylphrine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 49.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of p-Hydroxynorephedrine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 50.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Synephrine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 51.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Mannoic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 52.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 5-(2-Aminopropyl)−2-methylphenol with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 53.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Guanidinosuccinimide with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 54.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of Cathine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 55.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of l-histidine with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 56.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2-Propenoic acid, n-pentadecyl ester with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 57.

2D interactions of Heptanedioic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 58.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 2-Butenedioic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 59.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of 10-Octadecenoic acid with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

Fig. 60.

Two-dimensional interaction diagram of L- Alanine ethylamide, (S) with human maltase gluco‑amylase (PDB ID: 2QMJ).

4. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein preparation

In this molecular docking study, which aims to control metabolic disorders, two target proteins were selected: Human maltase-glucoamylase in complex with acarbose (PDB ID: 2QMJ) and human pancreatic alpha-amylase in complex with nitrite (PDB ID: 2QMK). The 3D structures of these proteins were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) [15]. The details are summarised in Table 1. The preparation was performed using YASARA software (version 19.12.14). The preparation process included the following steps: (i) calculation of Gasteiger charges, (ii) addition of hydrogen atoms and Kolman charges, (iii) removal of water molecules and heteroatom coordinates, and (iv) restoration of missing C-terminal oxygen atoms [1]. To ensure the structural integrity of the protein, preprocessing involved a series of careful steps: calibration of binding parameters, definition of bonds and bond orders, correction of incorrectly assigned elements, reconstruction of missing side chain loops, removal of superfluous chains, capping of uncapped C- and N-termini and formal charges for metal ions for optimal stabilisation [16]. Priority was given to hydrogen bonding in the optimisation strategy, while other factors were reduced by using AMBER14 for the field after hetero-group removal. The quality of the prepared proteins was assessed using the SiteMap application and the files were saved in pdbqt format for further analysis.

4.2. Ligands preparation

A total of 25 ligands were selected for this study, the 3D structures of which were taken from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Prior to screening, ligand preparation was performed using Maestro software [17], which included several important steps: the creation of 3D geometries, valence recognition and the identification of accessible tautomers. Furthermore, several parameters carefully include minimization of energy, hydrogen atoms addition and torsion angles calculation. The ligand structures were energetically minimised using a gradient of 0.05, assigning the correct bond orders and charges [18]. The geometry was optimized using the steepest gradient method over a total of 100 iterations.

4.3. Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed to identify potential ligands that could serve as inhibitors by targeting the binding sites of the selected proteins to treat metabolic disorders. The identification of binding sites was performed using the online web tool YASARA [19]. In contrast to conventional scoring approaches, this study focused on the interaction between the target receptor proteins and the ligands as determined by the positive binding energy scores. The Clean module was used to process the crystallised ligand coordinates and thus ensure optimal preparation for the subsequent analysis. In addition, Vina generated docking sites that were checked with the AMBER04 force field, which determined the atom types and confirmed their similarity to the original positions. The involvement of specific amino acids and the types of binding that contribute to intermolecular interactions between potent ligands and target proteins were visualised with the AMBER4 force field using ACCELRYS Discovery Studio [20].

Limitations

No in vitro experiments or animal studies were performed in the present study, which are crucial for validating the molecular docking results and confirming the biological activity of the identified interactions.

Ethics Statement

The authors have read and follow the ethical requirements for publication in Data in Brief and confirming that the current work does not involve human subjects, animal experiments, or any data collected from social media platforms.

CRediT Author Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships which have or could be perceived to have influenced the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgments

The first author Komal G. Lakhani acknowledges SERB, DST, Govt. of India & CII for Prime Minister Fellowship. Funding: This research was not financially supported by any governmental or private institution or funding organisation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships which have or could be perceived to have influenced the work reported in this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.dib.2025.111290.

Contributor Information

Rasmieh Hamid, Email: r.hamid@areeo.ac.ir.

Kirankumar P. Suthar, Email: kiransuthar@nau.in.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data Availability

References

- 1.Lakhani K.G., Prajapati P., Hamid R., Patel S.K., Dwivedi A., Suthar K.P. From millets to medicine: ADMET insights into diabetes management with P. sumatrense. Compd., Biocatal. Agricult. Biotechnol. 2024;61(3):103396. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh R., Gholipourmalekabadi M., Shafikhani S.H. Animal models for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: advantages and limitations. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2024;15 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1359685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A.D.A.P.P Committee, A.D.A.P.P. Committee:, 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes care. 2022;45(Supplement_1) S17-S38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olaokun O.O., Zubair M.S. Antidiabetic activity, molecular docking, and ADMET properties of compounds isolated from bioactive ethyl acetate fraction of Ficus lutea leaf extract. Molecules. 2023;28(23):7717. doi: 10.3390/molecules28237717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemente-Suárez V.J., Beltrán-Velasco A.I., Redondo-Flórez L., Martín-Rodríguez A., Tornero-Aguilera J.F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2023;15(12):2749. doi: 10.3390/nu15122749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvia M.G., Quatromoni P.A. Behavioral approaches to nutrition and eating patterns for managing type 2 diabetes: a review. Am. J. Med. Open. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.ajmo.2023.100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geervani P., Eggum B.O. Nutrient composition and protein quality of minor millets. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 1989;39:201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF01091900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahoo J.P., Mahapatra M. International year of millets-2023: revitalisation of millets towards a sustainable nutritional security. Technol. Agron. 2023;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav O., Singh D., Kumari V., Prasad M., Seni S., Singh R.K., Sood S., Kant L., Rao B.D., Madhusudhana R. Production and cultivation dynamics of millets in India. Crop Sci. 2024;64(5):2459–2484. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhawale R. Metabolomic profiling of drought-tolerant little millet (Panicum sumatrense L.) genotype in response to drought stress. Pharm. Innov. 2022;11:1754. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong L., Feng D., Wang T., Ren Y., Liu Y., Wang J. Inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase: potential linkage for whole cereal foods on prevention of hyperglycemia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8(12):6320–6337. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashtoh H., Baek K.-H. New insights into the latest advancement in α-amylase inhibitors of plant origin with anti-diabetic effects. Plants. 2023;12(16):2944. doi: 10.3390/plants12162944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R.J. Ouellette, J.D. Rawn, Principles of Organic Chemistry, Academic Press, Elsevier Sci.(2015). Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1829473/principles-of-organic-chemistry-pdf.

- 14.Horii S., Fukase H., Matsuo T., Kameda Y., Asano N., Matsui K. Synthesis and. alpha.-D-glucosidase inhibitory activity of N-substituted valiolamine derivatives as potential oral antidiabetic agents. J. Med. Chem. 1986;29(6):1038–1046. doi: 10.1021/jm00156a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burley S.K., Berman H.M., Kleywegt G.J., Markley J.L., Nakamura H., Velankar S. Humana Press; New York, NY, 1607: 2017. Protein Data Bank (PDB): the single global macromolecular structure archive, Protein Crystallography: Methods and Protocols; pp. 627–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulishankar A., Lakshmanan K. Data on molecular docking of naturally occurring flavonoids with biologically important targets. Data Br. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattar S.V., Adhoni S.A., Kamanavalli C.M., Kumbar S.S. In silico molecular docking studies and MM/GBSA analysis of coumarin-carbonodithioate hybrid derivatives divulge the anticancer potential against breast cancer. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020;9:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakhani K., Hamid R., Gupta S., Prajapati P., Prabha R., Patel S., Suthar K.P. Exploring the therapeutic mechanisms of millet in obesity through molecular docking, pharmacokinetics and dynamic simulation. Front. Nutr. 2024;11:1453819. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1453819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel C.N., Goswami D., Jaiswal D.G., Parmar R.M., Solanki H.A., Pandya H.A. Pinpointing the potential hits for hindering interaction of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein with ACE2 from the pool of antiviral phytochemicals utilizing molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. J. Mol. Graph. Modell. 2021;105 doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.107874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel C.N., Jani S.P., Jaiswal D.G., Kumar S.P., Mangukia N., Parmar R.M., Rawal R.M., Pandya H.A. Identification of antiviral phytochemicals as a potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitor using docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):20295. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99165-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.