Abstract

Liver disease is a major, and increasing, cause of death in the UK. The UK Chronic Liver Failure network (UK-CLIF) was developed as a multi-stakeholder network with the aim to advance cirrhosis research, with emphasis on geographical areas of high disease prevalence or limited research activity. The process involved network development through dissemination and snowball sampling techniques, with monitoring of network development and connections between participants, developed over two online meetings. Network membership included representatives from patients, carers, clinicians, researchers, R&D professionals, industry representatives, and the third sector. Subsequently, two facilitated in-person workshops were conducted with network participants. World Café methodology and participant dot voting was used to develop areas of priority and consensus in: (i) research infrastructure for cirrhosis clinical trials, (ii) clinical factors affecting research delivery, and (iii) research priorities for future trials. Thematic analysis demonstrated that the need for patient-centric trial materials, a lack of resource for clinicians to participate in research, and variability in the standard of inpatient care for cirrhosis, were barriers for cirrhosis clinical trials. Future activities for UK-CLIF include participation in a process of quality standard setting for inpatient care for cirrhosis, and coordination of a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership to develop research questions for liver cirrhosis.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, clinical trials, alcohol

Plain Language Summary

Liver disease is a growing problem in the UK, and rates of death have increased by a quarter since 2019. The aim of this project was to develop a network of people involved in clinical trials for advanced liver disease (cirrhosis), to help us deliver better quality studies and develop new treatments. Online meetings were held to develop the network, and then detailed workshops were held in Bristol and Liverpool with patients, carers, researchers, clinical trial experts and other people involved in clinical trials. These meetings found that clinical trials for liver patients should be tailored to patients, and there should be more researchers to do research. Additionally, the network will help to develop standards for patients with liver cirrhosis, so that liver care is similar across the UK, and also help to understand the most important research questions for liver patients in a project with the James Lind Alliance.

Introduction

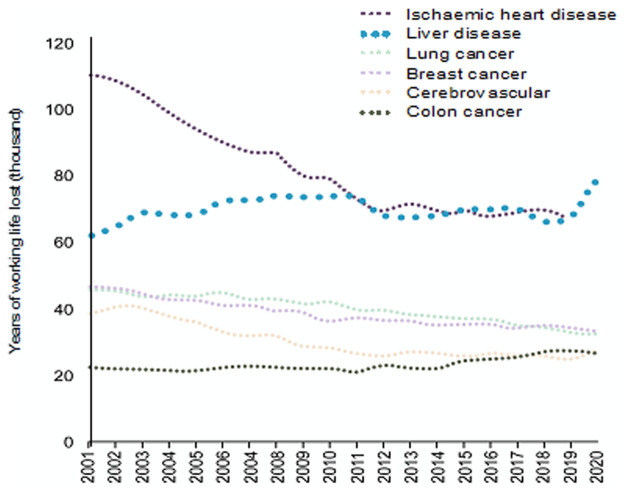

Liver disease is now the most common cause of premature death amongst non-communicable diseases in the UK ( Figure 1). The burden of liver disease has increased substantially since the Covid-19 pandemic, with mortality rates around ~25% higher in 2024 than 2019 1 . Moreover, it has been widely documented that there are grave inequities in the provision of liver care and clinical outcomes from cirrhosis. Inpatient mortality from cirrhosis varies widely between non-specialist hospitals in England, and mortality rates within 60-days of admission are several times higher than comparable admissions for stroke or ischaemic heart disease 2 .

Figure 1. Liver disease deaths are now the commonest cause of working years of life lost amongst non-communicable diseases (Data: Office for National Statistics, 2022).

In parallel, clinical trial performance in the UK, including within liver disease, has tailed off. As noted in the recent review of clinical trials by Lord O’Shaughnessy, within the last five years our relative performance in initiation and recruitment to phase 3 clinical trials has fallen with our relative ranking to other countries decreasing from 4 th to 10 th globally 3 . Within the area of liver cirrhosis a number of large clinical trials have been undertaken in the UK in recent years; however, new therapies for decompensated cirrhosis remain lacking and some large studies have closed early (e.g. NIHR award 16/99/02).

Novel therapeutic approaches to the management of liver cirrhosis and urgently needed, and to achieve this several aspects of clinical trial design and delivery may be innovated in the post-pandemic era. The overarching aim of the UK-CLIF project is to establish a nationwide, multi-stakeholder network to address shortfalls in, and improve delivery and impact of, clinical research in decompensated cirrhosis.

The specific objectives of UK-CLIF were to: (a) establish a prototype multi-stakeholder network to advance cirrhosis research, with emphasis on geographical areas of high disease prevalence or limited research activity; (b) co-develop consensus positions on fundamental aspects of cirrhosis research in the UK, such as research infrastructure for cirrhosis clinical trials and clinical factors affecting research delivery; (c) identify research priorities for future trials and collaborative research.

Methods

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients were involved in this project from the outset; two patients (RA, MS) were involved in the design of the proposal and were co-applicants to the NIHR HTA grant (155694). RA and MS also contributed to the design of the network and the workshops, and are co-authors of this manuscript. Additionally, over ten patients or members of the public contributed to the conduct of the workshops described below. RA and MS were also involved in the preparation of this manuscript, and in the design of online dissemination materials ( www.ukclif.org).

This project was not classified as research according to HRA criteria ( https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/) or by local R&D colleagues, hence informed consent was not sought from network participants.

Network development. Key stakeholders were identified by the project team, and contacted to disseminate details of the network and grow membership participation using snowball sampling techniques (e.g. respondent-driven sampling). The initial stakeholders included members from several key sectors involved in liver disease research: patient representatives, charitable organisations and the third sector (British Liver Trust, British Association for the Study of the Liver), NHS hepatologists, NHS hepatology trainees, NHS liver intensive care specialists, liver nurse specialists, liver dietetics specialists, liver physiotherapists, and representatives from contract research organisations (CROs) and clinical trial units (CTUs).

A prototype of the network was established through online meetings, and an online presence (website, branding, social media handle) was developed for growth of the network. Network mapping was conducted to monitor interactions and geographic representation; participants were asked if they had any connection with other meeting participants, and asked to categorise if this connection was a weak connection (aware of their work), or a strong connection (previous collaborative work). Network mapping was conducted after the first two online meetings, and compared with baseline.

Facilitated workshops. Two independently facilitated World Café workshops were held in geographically distinct areas, to explore consensus positions on: (i) research infrastructure for cirrhosis clinical trials, (ii) clinical factors affecting research delivery, and (iii) research priorities for future trials. The World Café approach is designed to facilitate consensus development in an open and shared process, enabling input from all involved, regardless of power dynamics 4 . Workshops had a duration of 2.5 hours, and had a standardised format:

Introductions around the room

Introduction to the UK-CLIF Network

Outline of how the consensus-building process would work

Participants rotating around facilitated discussions on the three topics

Four or five key priorities from the discussions distilled by facilitators

Participants ‘dot voting’ to select priority issues

Each of the facilitators ‘hosted’ the small group for one of the discussion topics, through each of the three rounds. Groups were organised so that people were allocated to each topic in turn, with a mix of health care professionals, researchers and patients/carers in each group. After 25 minutes’ discussion people were asked to move to their next group. The membership of each small group changed in each round, so that participants had the opportunity to discuss issues with different people for each topic.

During a break, the facilitators synthesised the three rounds of discussion at their table into four or five priority areas. When the participants reconvened, these were presented to the whole group and written up on flipcharts. Participants then carried out ‘dot voting’, with 8 votes per person to allocate between the 12 – 15 priorities identified. Each person could use their votes in any combination, from one vote for each of 8 priorities to 8 votes for one priority. Through this voting process, consensus positions and research priorities were established across the three themes.

Results

The development of network connections as measured by network mapping are shown in Figure 2. The findings of the facilitated workshops are outlined below.

Figure 2. Network evolution from baseline ( left panel), after 1 st online meeting ( centre panel), and after 2 nd online meeting ( right panel).

Geographic locations are approximated.

Results of the World Café workshops are summarised in Table 1. Thematic findings addressing (i) research infrastructure and recruitment, and (ii) clinical factors, affecting research delivery in cirrhosis are listed. Some issues were raised by participants at both meetings (left column); the issues that were only raised in one meeting are also listed (centre and right columns). Common themes were: the need for patient-centric trial designs, protocol and strategies for engagement, the lack of resource for clinicians to participate in research, and variability in the standard of inpatient care for cirrhosis which may impact the ‘control’ arm for interventional studies in this group.

Table 1. Summary of findings from World Café workshops.

| Common issues (Bristol and Liverpool) | Additional issues from Bristol

workshop |

Additional issues from Liverpool

workshop |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Research infrastructure and

recruitment ☐ Better information needed for patients on research trials and benefits of participating in ☐ Trials are not well designed to engage a wide range of patients ☐ Need to approach patients to join research at an appropriate point in their care journey ☐ The importance of involving families and carers in discussions about research participation ☐ There is generally low health literacy in the population so hard to engage patients

2a. Clinical factors affecting research delivery ☐ Lack of priority for research in NHS - focus on care delivery ☐ Low numbers of specialist nurses – both liver nurses and research nurses ☐ Lack of clinic space and physical resources for research ☐ Clinicians need information and encouragement to get involved e.g. research as regular item on

2b. Consistent standards of care ☐ Need for agreed liver disease care standards ☐ Better linking of care across primary, secondary and tertiary care ☐ Set up national registers of cirrhosis patients and trials

|

1. Research infrastructure and

recruitment ☐ Research to focus on what would most improve patients’ quality of life ☐ Research into prescribing and compliance with medication regimes ☐ The importance of psychological support to patients ☐ Engage more patients to advise on research ☐ Remote monitoring of patients as a key research area 2a. Clinical factors affecting research delivery ☐ Time and trust to facilitate collaboration with industry is lacking ☐ Research does not easily feed into practice changes even when successful ☐ Researchers to make more use of a wide range of channels, including social media to disseminate research |

1. Research infrastructure and

recruitment ☐ Perceived stigma of liver disease ☐ Research focus on early diagnosis and prognosis ☐ Need for research on precision/ personalised medicine ☐ Therapies needed to prevent cirrhosis complications ☐ Research into new ascites treatments 2a. Clinical factors affecting research delivery ☐ Lack of protected clinician time for research ☐ Lack of research training for professionals ☐ More network and collaboration between centres, regional networks and funding create 2b. Consistent standards of care ☐ Lack of national data on prevalence, patient numbers and outcomes |

Findings regarding (iii) research priorities in cirrhosis, were not analysed thematically as there was little cross-over between workshops; these data are presented in supplemental material. The top voted research priorities in the Bristol workshop were: greater use of quality of life as a trial endpoint, and de-prescription of medications as an intervention. The top priorities in the Liverpool workshop were: precision/personalised approaches to therapy (e.g. using -omics) and therapies preventing the first complication of cirrhosis. Individual voting scores for each workshop, and categorical data on participant type, are also presented in the underlying data 5 .

Discussion

This robust process described above has demonstrated stakeholder engagement, network development and facilitated discussion of consensus positions regarding fundamental aspects of liver cirrhosis research in England. The initial steps of network expansion let to coverage across most areas of England, with representatives including patients, carers, hepatologists, nurses, allied healthcare professionals, translational researchers, and representatives from industry and the third sector. Importantly, this diverse network was used to invite participants for the detailed, World Café workshops.

The independently facilitated workshops highlighted three themes, developed by consensus, affecting translational research delivery for liver cirrhosis: patient-centric trial design, research-focussed career pathways and standardisation of inpatient care. These will be discussed in turn below.

Patient-centric materials and trial design were raised, and voted for, at both the Bristol and Liverpool workshops. In particular, patient-centric processes were thought important to involve participants from underserved and hard to reach communities. Liver disease frequently affects groups that are underserved, predominantly through socio-economic factors. The median age of death from liver disease in the five most deprived areas of England and Wales is 62 years, compared with 71 years in the least deprived 6 . In other clinical areas, such as cardiovascular disease, when clinical trial recruitment was not representative of real-world practice translational benefits were not realised 7 . Therefore, there is a strong case to facilitate inclusion of hard to reach participants in cirrhosis trials, including co-design of trial protocols and patient-facing materials.

In particular, the need to adapt recruitment strategies for patients with alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) was discussed. The challenges of recruitment and retention of patients in this group has been described by investigators in the Unites States, although there are few UK trials targeting this group. A specific trial discussed was the AlcoChange study (ISRCTN 10911773), investigating a digital therapeutic in ARLD. Examples of patient-centric processes from this trial include remote consent, remote data collection and amenable visit schedules. The ongoing learning from this trial will priced valuable information for future studies in this patient group.

A perceived lack of prioritisation of clinical research within NHS trusts was also raised as a barrier. This ranged from lack of infrastructure and physical resources, research staff and protected clinician time. Of note, the recent O’Shaughnessy report on UK clinical trials 8 , and the response from the UK government 9 , recommends a ‘Clinical Trials Career Path’ to be integrated into the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. Additionally, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has launched competitive funding streams for infrastructure bids, such as the Commercial Research Delivery Centres bid, which are aligned with the aims to improve NHS research infrastructure articulated in our workshops as well as the O’Shaughnessy review. Nevertheless, this barrier to translational hepatology research merits ongoing attention.

The third aspect discussed, and voted for, was the variation in cirrhosis care between secondary and tertiary centres, the consequent need for agreed national care standards and, ideally, a prospectively maintained registry of cirrhosis patients. In particular, this variation impacts the delivery of trials where ‘standard care’ is the control – increasingly so as interventions become more complex. This variation in standard care leads to heterogeneity of outcomes and decreased statistical power to demonstrate the efficacy of potentially useful treatments. Importantly, to address this, the UK-CLIF network has partnered with the British Society for Gastroenterology Liver Committee to develop quality standards for inpatient care of decompensated cirrhosis – this project is in progress.

Finally, potential research priorities for the coming years were raised at both workshops (supplemental data). The highest-ranking topics were chosen by robust qualitative prioritisation methodology. However, it is clear for such a broad area as research questions a larger sample size is required. To achieve this, UK-CLIF has partnered with the James Lind Alliance to conduct a nationwide priority-setting process for liver cirrhosis ( https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/liver-cirrhosis/). This is an externally facilitated, transparent qualitative process, with balanced inclusion of patient, carer and clinician interests and perspectives. This process has commenced and will report in early 2025.

Ethics & consent

This project was not classified as research according to HRA criteria ( https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/) or by local R&D colleagues, hence formal ethical approval and informed consent was not required.

Funding Statement

This project is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) under its Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (Grant Reference Number 155694). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 3 approved]

Data availability

Details of the individual voting scores for each workshop, and categorical data on participant type, are presented as underlying data. There was no other data collected.

Underlying data

Underlying data: Figshare: Underlying data for ‘Decompensated liver cirrhosis research network (UK-CLIF): Building consensus for hepatology trials in the UK’ HTA166694 Extended data.docx https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26181128.v2 5

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0)

Author contributions

Project conception and design: HC, OT, GM; obtained funding: GM; workshop facilitation and data acquisition: HC, OT, GM; manuscript drafting: HC, OT, GM; manuscript review: all.

References

- 1. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities: Liver disease profile, April 2024 update. 2024; Accessed 15 thJune 2024. Reference Source

- 2. Roberts SE, John A, Brown J, et al. : Early and late mortality following unscheduled admissions for severe liver disease across England and Wales. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(10):1334–45. 10.1111/apt.15232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry: NHS patients losing access to innovative treatments as UK industry clinical trials face collapse. 2022; Accessed 15 thJune 2024. Reference Source

- 4. Maskrey N, Underhill J: The European Statements of Hospital Pharmacy: achieving consensus using Delphi and World Café methodologies. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2014;21(5):264–66. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta G: HTA166694 Extended data.docx. figshare. Dataset.2024. 10.6084/m9.figshare.26181128.v2 [DOI]

- 6. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities: The 2 nd atlas of variation in risk factors and healthcare for liver disease in England. 2017; Accessed 15 thJune 2024. Reference Source

- 7. Ferdinand KC, Elkayam U, Mancini D, et al. : Use of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in African-Americans with heart failure 9 years after the African-American Heart Failure Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(1):151–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Department of Health and Social Care: Commercial clinical trials in the UK: the Lord O’Shaughnessy review - final report. 2023; Accessed 15 thJune 2024. Reference Source

- 9. The Department of Health and Social Care: Full government response to the Lord O'Shaughnessy review into commercial clinical trials. 2023; Accessed 15 thJune 2024. Reference Source