Abstract

Objective

Decision fatigue (DF) can lead to impaired judgement, decreased diagnostic accuracy and increased likelihood of medical errors. Research on DF is scarce, and little is known about its nature in the clinical context. The objective of the present review was to provide a comprehensive framework to understand how the construct of DF in medical settings has been defined and measured. This review aimed to understand DF determinants and consequences and capture motivational factors overlooked in the existing reviews.

Design

Systematic and scoping review (ScR) with meta-synthesis.

Eligibility criteria

Empirical and non-empirical papers on clinical DF or related constructs directly impacting clinical decision-making were considered, with doctors of all ages, sexes and nationalities as participants. The Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses scoping review checklist has been applied and checked.

Information sources

Six databases were systematically searched by two independent researchers according to a predefined set of keywords.

Results

43 papers were included, of which 25 were empirical. The quantitative studies outnumber the qualitative ones and primarily involved residents in Europe/UK and North America. Internal medicine and primary care were the most studied disciplines. Only one sequential cross-sectional study measured DF in the medical setting, and all other studies addressed the construct indirectly. A conceptual analysis of clinical DF, including narrative contributions, a thematic analysis of the data extracted and a meta-synthesis, is provided. Clinical DF was investigated mostly by individual risk factors analysed through multiple intertwined determinants involving cognitive, emotional, behavioural, social and ethical aspects. Relevant risks, protective factors and negative outcomes circularly increasing DF are outlined.

Conclusions

The review gives solid arguments for developing a clear and coherent definition of clinical DF that allows the implementation of preventive targeted intervention.

PROSPERO registration number

This systematic review was pre-registered in PROSPERO on 8 November 2023 (available online at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023476190, registration number CRD4202347619).

Keywords: Physicians, Primary Care; Psychology, Medical; Health Policy; Public Health; Quality Improvement

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Decision fatigue (DF) was recognised as a factor leading to impaired judgement and increased medical errors in clinical settings, but it lacked a cohesive definition or theoretical framework.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This systematic review provides a novel descriptive definition of clinical DF that researchers can apply in future research and a comprehensive synthesis of the protective and risk factors and the consequences of DF.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study emphasises the need to validate clinical DF measures, exploring its cognitive, emotional and ethical dimensions. It highlights the importance of understanding determinants and protective factors to inform strategies like shared decision-making, supportive environments and training programmes. These insights can guide interventions to reduce DF, improve physician well-being and enhance patient care.

Introduction

Medical decision-making (DM) requires applying scientific knowledge with careful consideration of costs, risks and benefits. Current medical DM is characterised by heavy workloads,1 and the complexity of diseases exacerbates these challenges, especially in general practice.2 Physicians decide what is best for their patients within emotionally charged situations and share responsibilities with colleagues, patients and their families. They are called to consider people’s feelings, expectations and ethical values in treatment.

The demanding nature of DM is increasingly burdening for physicians who experience decision fatigue (DF). DF refers to transient cognitive and emotional dysregulation that can lead to decisional errors, posing risks to the physician’s well-being and patients’ health.3 The concept of DF assumes a limited capacity for human behaviour regulation4 and suggests that repeated decisions impair subsequent self-control and motivation.5 6 Scholars proposed psychological mechanisms of DF in two models describing self-control. The Strength Model of Self-Control5 speculates that self-control (necessary in DM, ie, for resisting impulse or delaying immediate reward seeking) diminishes under repeated decisions and creates a condition of reduced mental strength defined as ego depletion4 that impacts subsequent decisions. The alternative Process Model of Ego Depletion6 suggests that ego depletion may diminish the motivation to make efforts in repeated decisions, and self-control is allocated elsewhere.

Research on DF and its correlates has spread in economics and social sciences,7 and its importance in healthcare is growing.2 The review of Pignatiello et al3 highlighted a significant gap in the literature on DF, noting few studies and a lack of clear theoretical definitions. Moreover, Pignatiello et al3 did not focus on healthcare contexts, aiming to provide a broad conceptual definition. Starting from this evidence, the present systematic review intended to further examine the determinants and consequences of DF, with a specific interest in medicine. Physicians’ DM involves a specific emotional intensity and the constant need for quick and accurate DM under pressure. Considering the relevance of the motivational theory of DF in medicine, we expanded the search to include potential emotional components of a specific ‘clinical’ DF (eg, including keywords on compassion fatigue or emotional exhaustion).

Therefore, the objective of our review was to provide a comprehensive framework for DF that aligns with clinical complexities. This review aimed to understand how the construct of DF in medical settings has been defined and measured, provide an understanding of its determinants and consequences and capture motivational factors largely overlooked in the existing reviews. Moreover, this review intends to provide an overview of the outcomes of DF. In summary, the research questions were as follows:

RQ1: How has the construct of DF in medicine been defined and measured?

RQ2: Which determinant factors have been considered?

RQ3: What are the consequences (outcomes) of clinical DF?

Method

The systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)8 guidelines, its recent formulation9 and extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).10 This systematic review was pre-registered in PROSPERO on 8 November 2023 (available online at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023476190, registration number CRD4202347619).

A systematic literature review was conducted on Ebsco, PsychInfo, Scopus, MEDLINE, Pubmed, and Web of Science for papers on DF in medicine. We also searched the Cochrane Library and the above-mentioned databases for previous systematic literature reviews.

Search strategy

The systematic review started in November 2023. In light of the findings from a previous review,3 which identified a deficiency in defining DF and a gap in understanding this construct, the current systematic review has a dual focus. It examines studies that directly assess or define DF and those that measure or describe related constructs that directly impact DF, although without specifically measuring it.

To identify the papers, the search was based on the construct and the context of interest using MESH terms; the last Boolean search was performed on 15 November 2023, in all the databases using the following combination of terms: “Mental Fatigue AND Decision Making AND (Burnout, Psychological AND Burnout, Professional OR Occupational Stress) AND (Healthcare Professionals OR Health Personnel)”. A subsequent search was conducted to expand the results using the following combination of keywords:

(1) To identify the construct of interest, a Boolean search was performed using the following combination of terms. Moreover, following the findings of Pignatiello and colleagues,3 several different words were included in the search as being found to be related to DF (eg, mental fatigue or ego depletion): “decision fatigue” OR “mental fatigue” OR “cognitive fatigue” OR “cognitive effort” OR “mental exertion” OR “cognitive exertion” OR “mental exhaustion” OR “mental tiredness” OR “ego depletion” OR “choice fatigue” OR “choice overload” OR “emotional exhaustion” OR “emotion” OR “cognitive” OR “fatigue” OR “motivational” (with and without the subsequent part) AND “decision making” OR “decision-making” OR “decision overload” AND “burnout” OR “burn-out” OR “compassion fatigue” OR “moral distress”.

AND

(2) To identify the context of interest, a Boolean search was performed using the following combination of terms: “healthcare” OR “health service” OR “medical services” OR “healthcare setting” OR “healthcare worker” OR “healthcare professional” OR “healthcare provider” OR “health practitioner” OR “health personnel” OR “physician” OR “doctor” OR “interns” OR “resident” OR “residency” OR “medical student” OR “practising physician”.

These searches identified 575 studies. The keywords were translated into four languages (Italian, French, German and Spanish) and searched again in each database. No additional results were found. The references found in the studies were reviewed, and a hand search was conducted on December 15. Five additional articles were included, reaching a final of 580 papers.

Study selection

Studies were included if they addressed DF directly impacting clinical DM. In addition, worldwide literature was screened with the following inclusion criteria: (1) peer-reviewed articles, (2) in all languages and (3) involving physicians. The articles’ title, abstract and full text were screened independently by two reviewers (GM and JG). The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in table 1; no year limitations have been applied.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Construct | Studies on decision fatigue or related constructs directly impacting clinical decision-making (DM) or issues related to clinical DM. | Studies focused on related constructs without a direct impact on fatigue (eg, studies on the impact of DM on physicians’ career choices with no mention of fatigue). |

| Population | Studies on doctors or resident doctors of all ages, sexes and nationalities.Studies involving a combination of physicians and other healthcare professionals (ie, nurses, pharmacists, social workers), only if the results are distinguished and can be referred to the physicians. | Studies on medical students or other healthcare professionals than doctors (ie, nurses, pharmacists, social workers). Studies on a miscellaneous of physicians and other healthcare professionals if the results cannot be distinguished. |

| Study design | All types of study designs, including empirical (RCT, cross-sectional, longitudinal, qualitative and mixed-method study designs) and non-empirical studies* (opinion papers, commentary, editorial, professional guidelines). | Systematic reviews. |

| Type of publications | Studies published in all languages | Unpublished studies (dissertations, conference proceedings). |

These studies have been included to enrich the understanding of the research topic through descriptive and interpretive approaches, thus contributing to constructing a more complete picture of the available evidence and opening up possible future research developments.

RCTrandomised controlled trial

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers independently performed the systematic search and the data extraction. Before the data extraction, they were trained on the systematic review objectives and research questions, and familiarised with the keyword combinations and data extraction strategies. Before the data selection, the two coders learnt the inclusion/exclusion criteria and received training from a senior researcher on how to apply them to the extracted data. They worked with a senior researcher (NG) on their discrepancies to refine their interpretation of the criteria and reach a similar level of understanding.

A multiple testing phase approach has been applied to data selection (ie, papers inclusion) since this method increases the quality and the rigor of systematic reviews11 and allows to calculate the Cohen’s K multiple times.

Two researchers (GM and NG) coded the results section of every included paper ‘line-by-line’ and identified and extracted all the relevant data from the papers. To answer the first research question, we extracted data on the assessment of DF that were then analysed and summarised in the Results section. In addition, data about determinants and outcomes were extracted from the included studies to answer the second and third research questions. The data were organised in a table for each type of article (empirical quantitative studies, empirical qualitative studies, narrative papers). Each table was structured with the following columns: study data (authors, year, country), participants (specialty), contexts of the studies, constructs, measurement tools, determinants (risk factors), determinants (protective factors) and outcomes (see online supplemental tables 3–5).

Two coders conducted an inductive thematic coding12 13 on the determinants and outcomes extracted to derive higher-level categories by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the results, as suggested for mixed-methods reviews.14 After the familiarisation phase, the determinants were further categorised into risk and protective factors, while for the outcomes, a sub-coding was not required. Furthermore, the two coders categorised each risk and protective factor as individual (IF) or contextual (CF) factors. Individual factors encompass constructs related to characteristics or processes occurring within the individual. In contrast, contextual factors include environmental characteristics or external influences affecting DF (eg, workload, shifts, role clarity, coworker and supervisor support, electronic health record usability).

In the final step, the IF were further classified as cognitive (C), emotional (E), behavioural (B), socio-demographic (S) or ethical (ETH) factors. Cognitive factors refer to aspects related to mental processes such as perceptions, reasoning, memory and executive functions (eg, DM style or cognitive overload). Emotional variables pertain to emotions, feelings, moods and affective states experienced by individuals (eg, emotional exhaustion, empathy, anxiety). Behavioural variables encompass aspects associated with observable courses of action demonstrated by individuals in various situations (eg, coping strategies or inappropriate medical behaviours, such as overprescriptions). Socio-demographic variables fall under the individuals’ social and demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, education, income, ethnicity and marital status. Finally, ethical aspects are variables categorised as ethical principles, values, moral beliefs and ethical standards guiding behaviour and DM (eg, sense of responsibility to patients, fear of harm or moral distress). Cohen’s K was calculated to evaluate inter-coder reliability.

The data extracted and categorised by the thematic analysis were then involved in a meta-synthesis in which the analytical themes were consensually generated to synthesise the results (inductive phase).15

Assessment of methodological quality

The scoping aim of this systematic review does not require a mandatory assessment of the methodological quality of the screened studies.16

Results

Data description

Two researchers (GM and JG) independently searched all the databases, applying the MESH terms and combining keywords. The PRISMA flowchart illustrates the study screening and selection process (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses diagram.

The two researchers identified 580 studies in the databases and removed 157 duplicates. They selected the eligible articles in three phases. During the process, the kappa coefficient was calculated two times, following the approach suggested by Belur et al.11

In the first phase, two researchers independently evaluated 212 papers from the 423 extracted via titles, abstracts and keywords, applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. They reached an agreement level of κ=0.74 on 63 papers, calculated on a 2 (GM, JG) × 2 (included, excluded) contingency table. Sixty papers were excluded (reasons for exclusion are reported in figure 1) and three included. The 149 papers receiving an unclear evaluation have been examined by both judges via full text; 136 were excluded and 13 included. In case of controversy, the two coders discussed the study under analysis, revisiting the inclusion and exclusion criteria to clarify discrepancies. If disagreements persist, they consult the predefined criteria to ensure consistent application, addressing any ambiguities as needed. When consensus cannot be reached, a third independent researcher (NG) arbitrated the controversy to ensure consistency. The number of included papers after the first phase was then 16.

In the second phase, 31 papers were selected randomly, and the two researchers independently evaluated their full texts, reaching a good agreement (κ=0.84) calculated on a 2×2 contingency table. Twenty-nine were excluded and two included. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussions, thanks to the arbitration by a third judge (NG). After phase 2, the total number of included papers were 18.

In the third phase, one researcher (GM) evaluated the full texts of the remaining 180 papers; 20 were included and 160 excluded. Combining the included papers in the three phases, the count made 38; five were included by a hand search, after reviewing the references of the included studies, reaching a total of 43 papers. Twenty-five were empirical (19 quantitative, five qualitative studies and one mixed methods study) and 18 were non-empirical papers (see figure 2a).

Figure 2. Descriptive statistics of the included papers: studies characteristics, countries and specialities.

The quantitative studies were conducted worldwide but predominantly in Europe/UK and North America, while the qualitative studies were mostly conducted in Europe/UK (see figure 2b). The nationality of the non-empirical studies was not considered. Multiple medical disciplines were investigated, with more than one discipline involved in the same study (see figure 2c). Primary care and internal medicine were represented most, followed by acute care and surgery with orthopaedics and gynaecology. However, 35% of the research did not specify the considered disciplines.

Among the empirical studies, the quantitative studies outnumbered the qualitative ones and primarily involved residents. The cross-sectional design was prevalent among the quantitative studies, except for one sequential cross-sectional study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic with three evaluation time points.17 No randomised controlled trials (RCT) or experimental studies were found. Box 1 shows the included studies. Online supplemental table 3 reportes detailed information about quantitative studies, online supplemental table 4 reportes data of the qualitative studies, and online supplemental table 5 shows the characteristics of the narrative papers.

Box 1. List of the included studies (see online supplemental table 3–5 for more information and meta-synthesis data).

Quantitative studies

Fernandez-Miranda et al, 2023,17 Filipponi et al, 2022,35 Fortea et al, 2023,40 Hughes et al, 2020,27 Iannello et al, 2017, 55 Johnson et al, 2022, 23 Jusić, 2021,33 Kushnir et al, 2010,41 Lindfors et al, 2009,56 Masiero et al, 2018,34 Melnick et al, 2020,57 Pedersen, Ingeman and Vedsted, 2018,58 Peltzer, Mashego and Mabeba, 2003,37 Persson et al, 2019,28 Pogosova et al, 2022,39 Schwarzkopf et al, 2015,32Shanafelt et al, 2010,38 Soukup et al, 2018,29 Yoon, Rasinski and Curlin, 2010,59 Zutautiene et al, 202336

Qualitative studies

Hall et al, 2017,18 Johnson et al, 2022,23 Lauffen-burger et al, 2022,20 Loh, Lee and Goy, 2019,22 Tallentire et al, 2011,19 Wharne, 201721

Narrative papers

Arnsten and Shanafelt, 2021,26 Brush, 2018,48 Campbell, 2010,60 Childers and Arnold, 2019,61 Courvoisier, Merglen and Agoritsas, 2013,45 Dryden-Palmer et al, 2018,62 Dubash, Bertensh and Ho, 2020,30 Ehrmann et al, 2022,43 Field and Taylor, 2022,47 Huilgol et al, 2022,44 Johal and Danbury, 2020,46 Masiero et al, 2020,49 Moorhouse, 2020,31 Morris et al, 2021,50 Romdhani et al, 2021,51 Schweitzer et al, 2023,42 Waldman, Waldman and Carter, 2019,52 Weir et al, 2020,53

The qualitative studies mainly applied focus groups (n=2, with 518 and 619 participants, respectively) or semi-structured interviews (n=2; with 2120 and 1 participants21). One study adopted both approaches, examining seven senior residents in anaesthesiology with two focus groups and individual interviews.22 Another integrated 15 semi-structured interviews with 60 hours of ethnographic observation studies how doctors managed clinical uncertainty.23

The non-empirical papers are mainly narrative in nature (ie, commentary, viewpoint, editorial), focusing on anecdotal although detailed descriptions of the phenomena, concepts or theories without formal data collection or analysis. The non-empirical papers focused on various specialities, including acute care, primary care, psychiatry and cancer care, and developed considerations regarding residents, senior residents and attendings.

How the concept of DF has been defined and measured

This section addresses the first research question: ‘How has the construct of DF in medicine been defined and measured?’. Notably, only one quantitative sequential cross-sectional study17 directly measured DF using a self-reported psychometric tool. The Decision Fatigue Scale (DFS) instrument was initially developed for surrogates of critically ill patients24 and later adapted for nurses.25 Fernandez–Miranda et al17 modified the DFS for physicians, incorporating 10 items rated on a four-point Likert scale. However, only seven items demonstrated acceptable factor loadings and were included in the final composite score. Althought, DF was broadly defined as a reduced ability to make decisions and regulate behaviours due to repetitive DM tasks,17 the scale assesses DF as the difficulty in making decisions, which is mostly a consequence of DF than an operationalisation itself.24 Other studies evaluated DF indirectly, linking it to factors such as stress from managing uncertainty or ambiguity, emotional exhaustion, DM style, poor quality of life or low emotional intelligence (see online supplemental table 3 for a comprehensive list).

The qualitative studies did not directly address DF but explored it indirectly as interfering with the quality of the physicians’ work or as related to patient outcomes. For example, DF has been indirectly discussed as a negative result of the inability or inaccuracy to make decisions, acts of omission, time pressure and physician disagreements. For a full list, see online supplemental table 4. None of the qualitative studies analysed DF by asking participants to define it or observing its cognitive, emotional and behavioural components.

The non-empirical papers examined the concept of DF more directly than the empirical studies, describing the possible determinants and associated outcomes. These papers described DF as a result of willpower depletion, physical fatigue, burnout and repeated or difficult decisions, to mention some factors related to physicians’ clinical DM. Other factors are the workload, dysfunctional workplace, implementation of new procedures and pressure from peers or patients/families. Most of these papers described the impact of emotions (ie, uncertainty, shame, guilt) on clinical DM. Emotional issues are seen as leading to cognitive overload and cognitive bias, DF, conflicts in shared DM with colleagues or patients and relatives, and clinical errors. Impact on physicians’ well-being (leading to burnout, depression, clinical regret, moral distress) is described. One paper26 delved into the neurobiology of burnout, describing the alterations in the prefrontal cortex and related cognitive, emotional, behavioural and ethical outcomes. For a comprehensive list, refer to online supplemental table 5.

Thematic analysis and meta-synthesis of the determinants and outcomes of DF

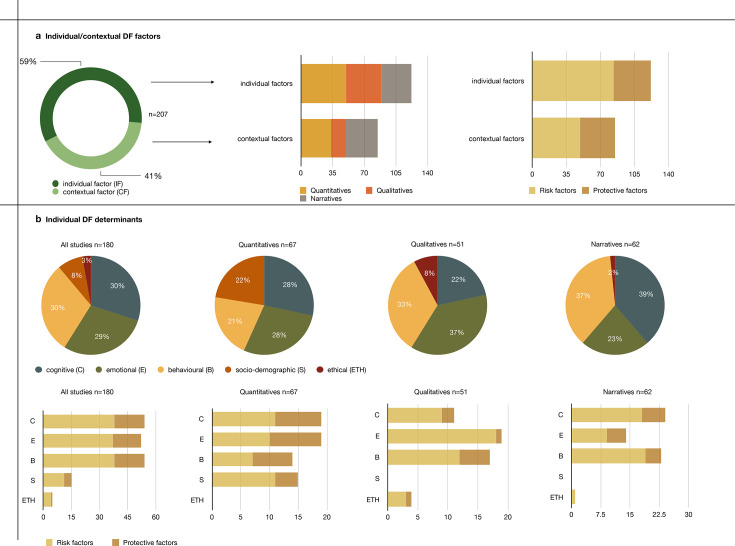

This section addresses the second (‘Which determinant factors have been considered?’) and third research questions (‘What are the consequences (outcomes) of clinical DF?’) through the thematic analysis and meta-synthesis approaches. The thematic analysis identified risk and protective factors of DF, with risk factors being the most extensively studied. Then, risk and protective factors were further categorised as individual (IF) or contextual factors (CF). The agreement on the IF and CF categories between the two judges was κ=0.87. Figure 3a shows the results of this step: in all included papers, DF was investigated to a greater extent by its individual determinant factors than by the contextual ones (n=122, 59% vs n=85; 41%).

Figure 3. Descriptive statistics of the thematic analysis: individual/contextual factors and individual decision fatigue determinants.

The second step of the thematic analysis further categorised both the individual risk and protective factors as having cognitive, emotional, behavioural and ethical components (see figure 3b upper part). The agreement on the attribution of these subcomponents between the two judges was κ=0.89. Behavioural, cognitive and emotional aspects are the most investigated. The ethical determinants were barely explored, mainly in a qualitative way (figure 3b). In quantitative studies, the cognitive, behavioural, emotional and socio-demographic determinants of DF were treated in a balanced way. In contrast, in qualitative studies, the emotional aspects are the most considered, followed by behavioural and cognitive aspects. Narrative papers focused almost equally on cognitive, behavioural and emotional aspects.

The meta-synthesis (see figure 4) highlithed that risk factors for DF encompass a range of individual and contextual elements. At the individual level, factors include ego or willpower depletion, where repeated DM exhausts mental resources; self-perceived medical errors, which can heighten stress and anxiety; uncertainty and risks inherent in medical practice; ethical challenges that demand careful deliberation; and emotional challenges, such as dealing with patient suffering or death. The most influential socio-demographic factors are being female and residents. Women in healthcare often face additional emotional and social pressures, while residents experience intense workloads and high levels of responsibility early in their careers. Contextually, the healthcare environment plays a crucial role: high patient volumes, time pressures, inadequate support and the organisational culture can all exacerbate the strain on healthcare professionals, making them more prone to DF.

Figure 4. Meta-synthesis of the decision fatigue protective/risk factors and outcomes.

Protective factors against DF include various individual, socio-demographic and contextual elements. Individually, strong communication skills, effective coping strategies, empathy and compassion, reliance on gut feelings, motivation, a strong professional identity, the ability to seek advice, self-control and awareness in DM, high self-esteem, and ambiguity tolerance all contribute to resilience. Socio-demographically, being male, maintaining good mental health, enjoying a good quality of life and ensuring good sleep quality are protective factors. Contextually, training in communication, DM and ethics, the availability of DM aids and collaborative tools, job control, professional experience and expertise and a supportive, safe workplace environment all help mitigate DF.

The outcomes of DF are far-reaching and detrimental, impacting both personal well-being and professional performance. Moreover, these negative outcomes increase the severity and persistence of DF itself. In this sense, the analysis of the papers allows us to introduce the idea of a negative circular causality, which leads those who struggle with DM to experience increased distress, further difficulty in making decisions and a heightened fear of making mistakes. Distress manifests through attention and reasoning deficits, burnout, interpersonal conflicts, compassion fatigue, regret, negative emotions, moral injury and trauma. Clinically, DF leads to impaired DM characterised by avoidant or impulsive choices, cognitive biases, decreased persistence, reliance on mental shortcuts, a lack of holistic approaches and poor self-regulation. These cognitive impairments translate into medical behaviours such as clinical errors, inappropriate prescriptions and referrals, impaired communication, negative attitudes towards patients, non-adherence to guidelines and a state of inaction. These outcomes highlight the critical need for strategies to mitigate DF in healthcare settings.

Discussion

The present systematic ScR and meta-synthesis aimed to resume the existing literature on clinical DF in medicine, focusing on its definitions, determinants and implications for clinical practice. The evidence that emerged from our search and analysis is a considerable heterogeneity in terms of study design and methodology, medical specialties, years of the physicians’ experience considered and constructs involved.

A critical aspect is that no one addresses clinical DF comprehensively, providing a definition within a theoretical model supporting the hypotheses or research questions and a definition that is used systematically. Only a few studies directly investigated DF as its primary focus,1727,31 while most considered related constructs. One unique quantitative study with a cross-sectional design17 directly measured DF on physicians using a modified scale created for caregivers and then adapted for nurses. However, the same authors highlighted a mismatch between the operationalisation of DF, which has been measured as the difficulty in making decisions,25 and its definition, which emphasises challenges in regulating behaviours due to repetitive DM tasks.17 In other words, the operationalisation of DF corresponds to the outcome of the concept (ie, problems with DM) instead of giving a definition itself. Neither qualitative nor empirical studies defined clinical DF or provided a clear theoretical framework to shape the concept. This finding confirms the scoping orientation of this review, which aimed to include more evidence on potential factors at stake in medicine compared with other work settings.

The analysis of clinical DF’s risk and protective factors identified contextual and individual factors with intertwined psychological dimensions. Quantitative studies were all cross-sectional; no cohort studies, experimental studies or RCTs were found. According to the available evidence, organisational factors relevant to DM could negatively impact physician’s well-being and may induce fatigue. Data showed that workload in critical and end-of-life care,32 in primary care33 and decision demands in primary care33 can increase emotional exhaustion. Individual issues are also linked to some specific critical DM styles. In particular, a small study on 23 healthcare professionals in acute care showed that avoidant DM styles with alexithymia predict burnout34 and an online investigation on miscellaneous specialists showed that maximising DM style contributed to an increased risk of compassion fatigue.35 More extensive studies confirm such data. DM authority and decision latitude (namely, the working individual’s potential control over tasks and conduct) appear protective factors for hospital physicians’ mental health.36 Furthermore, we observed that being female represents a risk factor among physicians for emotional dysregulation (particularly in the development of compassion fatigue17 and burnout37) and, consequently, for DF. Interestingly, consistent data from surgeons show that emotional exhaustion can increase the risk of self-reported medical errors.38 The same effect has been confirmed in non-adherence to clinical guidelines in general practice and cardiology,39 with an effect that appears to be bidirectional and may lead to the field as neurology to decision regrets.40 Findings of an extensive study on family physicians suggest poor-quality DM increases the likelihood of inappropriate medical behaviours.41 Overall, results from quantitative literature showed the influence of combined multiple psychological determinants, particularly emotion-related issues, besides organisational aspects such as risk and protective factors. Moreover, the relationship between decisional challenges and emotional issues in DM seems bidirectional. Considering the methodological nature of the reviewed evidence, which does not allow a causality conclusion, these data should be taken with some precautions and tested by further research involving RCTs.

Qualitative studies involved thematic analysis of recorded interviews,20,23 ethnographic observations,23 focus groups18 19 22 or mixed methods.23 The studies in this review indirectly approached DF, exploring how internal factors impacted DM abilities and stressing further the negative impact of emotional exhaustion on the cognitive function in DM. A study involving GPs showed how emotional aspects of burnout (ie, lack of empathy) affect negative attitudes, inappropriate referrals or patient safety.18 A qualitative nested study of mixed-method research conducted in internal medicine23 further deepens the weight of emotional factors. The study of Johnson et al23 highlights how diagnostic errors are influenced by how uncertainty-related anxiety in DM interacts with the fear of peer or senior judgement and the need to protect professional reputation (ie, ‘saving face’). Those results are consistent with other studies in the same field, showing that professional pressure tends to induce emotional states of guilt, shame and inadequacy in critical situations, increasing inappropriate drug prescriptions during night shifts.20 Similar results were found in two focus-group studies in anaesthesiology22 and acute care setting,19 where the ethical challenges in highly demanding professional roles emerge as core themes impacting DM ability and appropriateness of care. Protective factors highlighted by those studies appear to be individual and emotion-centred, including supporting be empathy, motivation, communication skills, openly acknowledging uncertainty and feeling protected and supported in the workplace.

Narrative studies are essentially editorials or viewpoints published in leading medical journals that broaden the picture and confirm what has emerged so far. The papers suggest that self-perceived clinical errors seem to impact physicians’ health by causing emotional dysregulation, which in turn increases future cognitive and decisional fatigue, thereby increasing the risk of medical errors. One paper offers a theoretical explanation of DF centred on the ego depletion theory5 and argues that willpower should be supported by supporting individual strengths in self-control.42 If reducing the roots of cognitive load is acknowledged as a critical opportunity offered by artificial intelligence in medicine,43 44 the relevance of DM regrets45 or ethical DM in conflictual situations is stressed.46 Furthermore, the decision climate, interprofessional cooperation and communication skills are considered risk and protective factors to be implemented in medical education.47 Contextual protective factors for DF include organisational improvements in work or shifts31 and team managing skills in communication and DM.3031 43 44 46,53

A final aim of our review was the identification of the consequences of clinical DF. The outcomes of DF are described in terms of cognitive errors, clinical errors and emotional impacts. Moreover, DF is suggested to function as a risk factor for burnout31 and a condition potentially caused by burnout.30 The papers’ meta-analysis introduces indeed the idea of negative circular causality (See figure 4). This idea is confirmed by the bidirectional causality between burnout and DF found in quantitative studies and by identifying the deleterious emotional impact of errors outlined by qualitative studies and narrative papers. In other words, those struggling with DM may experience increased distress, exacerbating their difficulties and heightening their fear of making mistakes.

This process aligns with the theoretical foundations of DF.5 6 Namely, the process seems characterised by a lack of individual willpower caused by workload and worsened by a process of negative interactions with motivation involving multiple psychological aspects. Even though they have been proposed as opposing features, self-control and motivational dimensions are not in conflict. For example, Vohs et al54 suggested that motivation is a fundamental ingredient of self-regulation and may be effective at substituting willpower. In this vein, even in a condition of ego depletion, an individual may be able to self-regulate effectively if motivation is high. The results of this systematic review and those theoretical correspondences allow us to formulate a descriptive definition of clinical DF: a multifaceted cognitive and motivational process affecting a physician’s DM ability, driven by contextual and individual factors, leading to a circular relationship with psychological distress and increased risk of errors in healthcare. This might be a starting point for developing a validated, comprehensive definition of clinical DF and operationalising the concept in future research.

DF has relevant ethical implications for clinical training and policy. Results show that ignoring DF in a medical setting could lead to an increased risk of medical errors and futility, potentially causing harm to the patients and violating the principle of equity in the distribution of health resources. Furthermore, DF appears to be linked bi-directionally with emotional exhaustion and can expose physicians to serious health issues. The DF process outlined by this review, identifying DF risk, protective factors and outcome and defining the constructs as a process offers several opportunities to prevent and contain it that should be the focus for future research in the field.

Limitations

One limitation pertains to the search strategy that may not encompass all relevant variations and synonyms for DF and related constructs, potentially leading to missing some studies. Moreover, while keywords were translated into four languages, translation nuances and database indexing in non-English languages could result in missing studies not captured by translated terms. Another limitation involves the selection criteria. Limiting the inclusion of studies involving physicians potentially led to missing insights from other healthcare professionals that could contribute to understanding DF. Moreover, including diverse study designs (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods) can introduce heterogeneity that complicates the synthesis and comparison of results. Furthermore, it should be noted that the type of studies involved (ie, the absence of any RCT or experimental study) and the metasynthesis do not allow causal inference concerning risk and protective factors and DF outcomes. However, the scoping aim of the review was to provide a full insight into this phenomenon.

Conclusions

Clinical DF represents a complex and multifaceted phenomenon with significant implications for clinical practice and patient outcomes. Although the present review, conducted in clinical DM contexts, provides a descriptive definition of clinical DF, it also highlights the need for future operationalisation of the concept, the test and the validation of the corresponding measure. Such a line of research would represent the starting point to reflect the composite nature of the construct, integrating insights from diverse theoretical perspectives and encompassing cognitive and motivational dimensions, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of this multifaceted phenomenon as influenced by internal and external factors. Looking ahead, future perspectives suggest the need for increasing data collection on emotional and ethical dimensions, as well as a deeper exploration of protective factors to mitigate the effects of DF. This would give the basis to develop the research in this field further, discovering the determinants and consequences of DF and determining the relationships between this concept and other related concepts (eg, burnout, distress).

Such a programme will provide information with potential practical implications. Organisational policies and practices should be designed to support physicians in managing DF and promoting high-quality patient care. Strategies to promote physician well-being (such as fostering shared DM, creating a supportive environment, implementing training programmes to enhance communication and DM skills) and reducing DF may hold promise. Researchers, clinicians and policymakers can collaborate to develop effective interventions and support systems that enhance physician well-being and improve patient care by advancing our understanding of DF and its determinants.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

References

- 1.Ancker JS, Edwards A, Nosal S, et al. Effects of workload, work complexity, and repeated alerts on alert fatigue in a clinical decision support system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:36. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0430-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritz C, Sader J, Cairo Notari S, et al. Multimorbidity and clinical reasoning through the eyes of GPs: a qualitative study. Fam Med Community Health. 2021;9:e000798. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2020-000798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pignatiello GA, Martin RJ, Hickman RL. Decision fatigue: A conceptual analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25:123–35. doi: 10.1177/1359105318763510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, et al. Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1252–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The Strength Model of Self-Control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:351–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inzlicht M, Schmeichel BJ. What Is Ego Depletion? Toward a Mechanistic Revision of the Resource Model of Self-Control. Pers Psychol Sci. 2012;7:450–63. doi: 10.1177/1745691612454134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inzlicht M, Schmeichel BJ, Macrae CN. Why self-control seems (but may not be) limited. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belur J, Tompson L, Thornton A, et al. Interrater Reliability in Systematic Review Methodology: Exploring Variation in Coder Decision-Making. Sociol Methods Res. 2021;50:837–65. doi: 10.1177/0049124118799372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs GR. Analysing qualitative data. London: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivas C. In: Researching society and culture. Seale C, editor. London: Sage; 2018. Finding themes in qualitative data; pp. 429–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6:61. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Colquhoun H, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. 2021;10:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández-Miranda G, Urriago-Rayo J, Akle V, et al. Compassion and decision fatigue among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in a Colombian sample. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0282949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall LH, Johnson J, Heyhoe J, et al. Exploring the Impact of Primary Care Physician Burnout and Well-Being on Patient Care: A Focus Group Study. J Patient Saf. 2020;16:e278–83. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Skinner J, et al. Understanding the behaviour of newly qualified doctors in acute care contexts: Behaviour of newly qualified doctors. Med Educ. 2011;45:995–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauffenburger JC, Coll MD, Kim E, et al. Prescribing decision making by medical residents on night shifts: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2022;56:1032–41. doi: 10.1111/medu.14845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wharne S. A Process You May be Entering’ – Decision-Making and Burnout in Mental Healthcare: an Existentially Informed Hermeneutic Phenomenological Analysis. Exist Anal. 2017;28:135–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh LWW, Lee JSE, Goy RWL. Exploring the impact of overnight call stress on anaesthesiology senior residents’ perceived ability to learn and teach in an Asian healthcare system: A qualitative study. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2019;26–27:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tacc.2019.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson MW, Gheihman G, Thomas H, et al. The impact of clinical uncertainty in the graduate medical education (GME) learning environment: A mixed-methods study. Med Teach. 2022;44:1100–8. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2058383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickman RL, Pignatiello GA, Tahir S. Evaluation of the Decisional Fatigue Scale Among Surrogate Decision Makers of the Critically Ill. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40:191–208. doi: 10.1177/0193945917723828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pignatiello GA, Tsivitse E, O’Brien J, et al. Decision fatigue among clinical nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:869–77. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnsten AFT, Shanafelt T. Physician Distress and Burnout: The Neurobiological Perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:763–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes J, Lysikowski J, Acharya R, et al. A Multi-year Analysis of Decision Fatigue in Opioid Prescribing. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1337–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson E, Barrafrem K, Meunier A, et al. The effect of decision fatigue on surgeons’ clinical decision making. Health Econ. 2019;28:1194–203. doi: 10.1002/hec.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soukup T, Gandamihardja TAK, McInerney S, et al. Do multidisciplinary cancer care teams suffer decision-making fatigue: an observational, longitudinal team improvement study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027303. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubash R, Bertenshaw C, Ho JH. Decision fatigue in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas . 2020;32:1059–61. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moorhouse A. Decision fatigue: less is more when making choices with patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:399. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X711989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzkopf D, Westermann I, Skupin H, et al. A novel questionnaire to measure staff perception of end-of-life decision making in the intensive care unit--development and psychometric testing. J Crit Care. 2015;30:187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jusic M. Burnout Among Healthcare Professionals in Bosnia and Herzegovina. JCRHSS. 2021;4:152–63. doi: 10.12944/CRJSSH.4.2.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masiero M, Cutica I, Russo S, et al. Psycho-cognitive predictors of burnout in healthcare professionals working in emergency departments. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:2691–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filipponi C, Pizzoli SFM, Masiero M, et al. The Partial Mediator Role of Satisficing Decision-Making Style Between Trait Emotional Intelligence and Compassion Fatigue in Healthcare Professionals. Psychol Rep. 2024;127:868–86. doi: 10.1177/00332941221129127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zutautiene R, Kaliniene G, Ustinaviciene R, et al. Prevalence of psychosocial work factors and stress and their associations with the physical and mental health of hospital physicians: A cross-sectional study in Lithuania. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1123736. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1123736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peltzer K, Mashego T, Mabeba M. Short communication: Occupational stress and burnout among South African medical practitioners. Stress Health. 2003;19:275–80. doi: 10.1002/smi.982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pogosova NV, Isakova SS, Sokolova OY, et al. Factors affecting the uptake of national practice guidelines by physicians treating common CVDS in out-patient settings. Kardiologiia. 2022;62:33–44. doi: 10.18087/cardio.2022.5.n1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fortea J, García-Arcelay E, Garcia-Ribas G, et al. Burnout among neurologists caring for patients with cognitive disorders in Spain. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0286129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kushnir T, Kushnir J, Sarel A, et al. Exploring physician perceptions of the impact of emotions on behaviour during interactions with patients. Fam Pract. 2011;28:75–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schweitzer DR, Baumeister R, Laakso E-L, et al. Self-control, limited willpower and decision fatigue in healthcare settings. Intern Med J. 2023;53:1076–80. doi: 10.1111/imj.16121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehrmann DE, Gallant SN, Nagaraj S, et al. Evaluating and reducing cognitive load should be a priority for machine learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2022;28:1331–3. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01833-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huilgol YS, Adler-Milstein J, Ivey SL, et al. Opportunities to use electronic health record audit logs to improve cancer care. Cancer Med. 2022;11:3296–303. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courvoisier D, Merglen A, Agoritsas T. Experiencing regrets in clinical practice. Lancet. 2013;382:1553–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johal HK, Danbury C. Conflict before the courtroom: challenging cognitive biases in critical decision-making. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:e36. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field E, Taylor T. The problem with paradoxes: The hidden costs of fatigue. Med Educ. 2022;56:967–9. doi: 10.1111/medu.14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brush JE. Is the Cognitive Cardiologist Obsolete? JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:673–4. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masiero M, Mazzocco K, Harnois C, et al. From Individual To Social Trauma: Sources Of Everyday Trauma In Italy, The US And UK During The Covid-19 Pandemic. J Trauma Dissociation. 2020;21:513–9. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1787296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris AH, Stagg B, Lanspa M, et al. Enabling a learning healthcare system with automated computer protocols that produce replicable and personalized clinician actions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:1330–44. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romdhani M, Kohler S, Koskas P, et al. Ethical dilemma for healthcare professionals facing elderly dementia patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Encephale. 2022;48:595–8. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2021.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waldman RA, Waldman SD, Carter BS. When I say… moral distress as a teaching point. Med Educ. 2019;53:430–1. doi: 10.1111/medu.13769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weir CR, Taber P, Taft T, et al. Feeling and thinking: can theories of human motivation explain how EHR design impacts clinician burnout? J Am Med Inform Assoc . 2021;28:1042–6. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, Schmeichel BJ, et al. Making choices impairs subsequent self-control: a limited-resource account of decision making, self-regulation, and active initiative. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:883–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iannello P, Mottini A, Tirelli S, et al. Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress. A study among Italian practicing physicians. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1270009. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindfors PM, Heponiemi T, Meretoja OA, et al. Mitigating on-call symptoms through organizational justice and job control: a cross-sectional study among Finnish anesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:1138–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melnick ER, Harry E, Sinsky CA, et al. Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability as a Predictor of Task Load and Burnout Among US Physicians: Mediation Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23382. doi: 10.2196/23382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pedersen AF, Ingeman ML, Vedsted P. Empathy, burn-out and the use of gut feeling: a cross-sectional survey of Danish general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020007. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon JD, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA. Conflict and emotional exhaustion in obstetrician-gynaecologists: a national survey. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:731–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.037762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campbell DA. Physician wellness and patient safety. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1001–2. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e06fea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Childers J, Arnold B. The Inner Lives of Doctors: Physician Emotion in the Care of the Seriously Ill. Am J Bioeth . 2019;19:29–34. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1674409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dryden-Palmer K, Garros D, Meyer EC, et al. Care for Dying Children and Their Families in the PICU: Promoting Clinician Education, Support, and Resilience. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19:S79–85. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.