Abstract

Abstract

Purpose

The NCDzz study is a prospective cohort of people living with and without HIV attending primary care clinics in Zambia and Zimbabwe and was established in 2019 to understand the intersection between noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and HIV in Southern Africa. Here, we describe the study design and population and evaluate their ideal cardiovascular health (ICVH) using the Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score according to the American Heart Association.

Participants

Antiretroviral therapy-naïve people living with HIV (PLWH) and people living without HIV (PLWOH) 30 years or older were recruited from three primary care clinics in Lusaka and Harare, and underwent comprehensive clinical, laboratory and behavioural assessments. All study measurements are repeated during yearly follow-up visits. PLWOH were recruited from the same neighbourhoods and had similar socioeconomic conditions as PLWH.

Findings to date

Between August 2019 and March 2023, we included 1100 adults, of whom 618 (56%) were females and 539 (49%) were PLWH. The median age at enrolment was 39 years (IQR 34–46 years). Among 1013 participants (92%) with complete data, the median LS7 score was 11/14 (IQR 10–12). Overall, 60% of participants met the criteria of ICVH metrics (5–7 ideal components) and among individual components of the LS7, more females had poor body mass index (BMI) than males, regardless of HIV status (27% vs 3%, p<0.001). Our data show no apparent difference in cardiovascular health determinants between men and women, but high BMI in women and overall high hypertension prevalence need detailed investigation. Untreated HIV (OR: 1.36 (IQR 1.05–1.78)) and being a Zambian participant (OR: 1.81 (IQR 1.31–2.51)) were associated with having ICVH metrics, whereas age older than 50 years (OR: 0.46 (IQR 0.32–0.65)) was associated with not having ICVH metrics.

Future plans

Our study will be regularly updated with upcoming analyses using prospective data including a focus on arterial hypertension and vascular function. We plan to enrich the work through conducting in-depth assessments on the determinants of cardiovascular, liver and kidney end-organ disease outcomes yearly. Additionally, we seek to pilot NCD interventions using novel methodologies like the trials within cohorts. Beyond the initial funding support, we aim to collect at minimum yearly data for an additional 5-year period.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGIC STUDIES, HIV & AIDS, Cardiovascular Disease, Risk Factors

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Comparison group of people living without HIV.

Newly diagnosed people living with HIV engaging in care at time of enrolment.

Fewer older adults (≥50 years) due to population demographics.

Clinic-community based cohort making results limited in generalisability.

Use of assessment tools (body mass index, diet, physical activity) developed in Western populations.

Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) represent the leading cause of deaths globally, resulting in approximately 41 million deaths annually.1 Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, respiratory diseases and diabetes account for over 80% of all premature NCD deaths, disproportionally affecting low- and middle-income countries.2 Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is seeing increasing trends in urbanisation and lifestyle changes promoting reduced physical activity, unhealthy diets, diabetes, obesity and hypertension, which are traditional risk factors for CVDs.1 The burden of CVD’s in SSA is rising, with events occurring at earlier onset when compared with high-income countries.3 The growing trend in CVD risk factors in settings with generalised HIV epidemics contributes to the collision of these disease epidemics in SSA.

People living with HIV (PLWH) have been shown to have a twofold risk of dying from CVDs when compared with age-sex matched HIV-negative counterparts, however, data have been derived from predominantly Caucasian male populations in European and North American studies.4 5 The availability of data on CVDs among PLWH and HIV-negative counterparts in SSA is scarce and is compounded by the lack of outcome data assessing the role of traditional risk factors on end-organ disease. Several studies from SSA have demonstrated a high burden of traditional CVD risk factors including hypertension, obesity and dyslipidaemia, but nearly all report low CVD risk scores using the 10-year Framingham and the 5-year DAD risk scores.6,9 These observations call for dedicated studies to assess the epidemiology of CVDs among the ageing HIV population, and further assessment of traditional CVD risk scores specific for the African context.9

Southern Africa faces a unique challenge, having the largest antiretroviral therapy (ART) programme globally, with the largest use of contemporary ART regimens, which have been associated with metabolic side-effects, that contribute to the growing NCD burden.10 11 Projections suggest that deaths due to CVD-related NCDs will exceed those due to communicable, maternal, perinatal and nutritional diseases combined by 203012 and the NCD and HIV disease syndemics could exacerbate an already fragile healthcare system within the region.1 Leveraging the existing International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in Southern Africa collaboration,13 this NCDzz cohort was set up to answer key questions on CVDs and bidirectional associations with key NCDs, including metabolic diseases, kidney, liver and mental health conditions. In this paper we present the study design, participants and preliminary results on ideal cardiovascular health (ICVH) from our evolving cohort.

Cohort description

The cohort was established under the framework of the IeDEA-Southern Africa collaboration and contributes to the overarching NCDs and comorbidity research agenda of the network.13 Between August 2019 and March 2023, we consecutively enrolled ART-naïve PLWH and people living without HIV (PLWOH) attending three primary care clinics in urban Zambia and Zimbabwe. The cohort was established to lay foundations for an epidemiological evaluation on the burden of NCDs and modifiable risk factors with long-term follow-up of patients initiating ART and accessing health services at primary healthcare facilities in Zambia and Zimbabwe. This pilot work will be able to inform larger intervention trials for the prevention and management of NCDs at primary care facilities in Southern Africa where large numbers of HIV-infected adults receive care.

Study settings

Kalingalinga Health Centre, Lusaka, Zambia

Kalingalinga Health Centre is an urban public sector primary care clinic with approximately 8247 PLWH ≥15 years receiving HIV care in March 2023.

Matero Level 1 Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia

Matero Level 1 Hospital is an urban public sector health facility with one of the largest ART-programmes in Zambia with approximately 14,392 PLWH ≥15 years receiving HIV care in March 2023.

Newlands Clinic, Harare, Zimbabwe

Newlands Clinic, operated by the Ruedi Luethy Foundation, is a specialised outpatient HIV clinic in a public–private partnership with the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health and Child Care since 2004. The clinic serves the wider community in Harare and surrounding towns including Chitungwiza and Norton. As of March 2023, the clinic followed 7516 PLWH >15 years. The detailed operations of the clinic are described elsewhere.14

Patient and public involvement

Patients and representatives from the selected clinic communities were invited to attend sensitisation meetings to discuss the research project prior to implementation. Attendees were invited to ask questions regarding the study, which were addressed by the research team. Patient-level results are communicated to study participants. Findings from the study will be disseminated to relevant local and national groups including policymakers and key stakeholders.

Study participants and recruitment

We aimed to include 600 PLWH and 600 PLWOH aged 30 years or older. This sample size would allow us to see a 20% difference in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome at 80% power, accounting for attrition during follow-up years. Participants were consecutively screened and enrolled on HIV provider-initiated testing and counselling, voluntary counselling and testing, maternal and child health and outpatient department services provided at the respective clinics, and through self-referral or provider referral from other clinics to the study sites (figure 1). PLWOH were recruited from the same neighbourhoods and had similar socioeconomic conditions as PLWH. Inclusion criteria for PLWH were no prior history of ART use or ≤4 weeks of ART use. Yearly follow-up visits are conducted at all sites (online supplemental S1).

Figure 1. Distribution of screening locations for ART-naïve people living with and without HIV. ART, antiretroviral therapy; MCH, maternal and child health; OPD, outpatient department; PITC, provider-initiated testing and counselling; PLWOH, people living without HIV; PLWH, people living with HIV; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Data collection

Data were collected using a combination of paper and electronic forms and were all captured in REDCap (www.project-redcap.org). Qualified personnel including research clinicians, nurses, research associates, treatment supporters and data associates received comprehensive trainings on data collection for anthropometrics, clinical assessments, point-of-care blood measurements, lifestyle and behavioural screening (table 1; online supplemental S2). Participant interviews lasted approximately 1.5–2.5 hours and participants were reimbursed for time spent at the clinic for study procedures. Individual concepts for data analysis are approved by the study scientific working group and IeDEA-SA steering committee.

Table 1. Cardiovascular health data collection measures and threshold values.

| Variable | Instrument | Outcomes |

| Blood pressure (BP)* | Omron Bronze BP5100 | Pre-hypertensive: systolic blood pressure (SBP: 130/139 mm Hg) and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP: 85/89 mm Hg)Hypertensive: 140 and/or 90 mm Hg on at least two repeated examinations27 |

| Height* | Seca 0123 stadiometer | – |

| Weight* | Seca Robusta 813 digital scale | – |

| Body mass index (BMI) | Derived from height and weight | Underweight: <18.5 kg/m2Normal: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2Overweight: 25–29.9 kg/m2Obese: ≥30 kg/m228 |

| Hip circumference(HC) | Standard tension tape measure | – |

| Waist circumference*(WC) | Standard tension tape measure | Central obesity29WC≥80 cm in femalesWC≥94 cm in males |

| Waist/hip ratio (WHR) | Derived from waist and hip circumference | WHR>0.85 in femalesWHR>0.90 in males |

Dyslipidaemia*

|

Alere Afinion 2 analyzer OR Cobas Beckman Coulter AU480 chemistry analyzer | Total cholesterol: 6.2 mmol/LLDL: 4.1 mmol/LHDL: <1.03 mmol/L in males and <1.29 mmol/L in femalesTriglycerides: ≥1.7 mmol/L |

| Fasting plasma glucose (FPG)* | Cobas Beckman Coulter AU480 chemistry analyzer or Cobas Integra 400 plus | Diabetes was defined as having a confirmedFPG≥7 mmol/L |

| Physical activity | WHO Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) | Physical activity was calculated as the total metabolic equivalent per minute per week (MET-min/week). Poor physical activity was defined as having <600 MET-min/week |

| Diet | WHO STEPS survey | Unhealthy diet was defined as having less than 4.5 servings of fruits or vegetables a day |

| Smoking | WHO STEPS survey | Cigarette smoking status was characterised as never, former or current |

Procedures: Blood pressure: patients were asked to sit in a resting position for 15 minutes min with legs uncrossed. Three measurements were taken 3-minutes min apart. The average of the three measures was taken as the final systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Height: Mmeasured in centimeterscentimetres with 2two decimal places. Patients were asked to stand without footwear or head gear with feet together and heaels against the back board. The measureing arm was placed onto the head of the participant and height was recorded in centimeterscentimetres to the exact point. Weight: Mmeasured in kilograms (kg) with 1one decimal place. Patients were asked to stand without footwear on the digital scale. Waist circumference: Tthe measurement was taken directly over the skin or over light clothing. The tape was wrapped around the patient positioned at the midpoint of the iliac crest and the lower rib margin and measured in centimeterscentimetres.30 Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides: Bblood draw was performed on patients after ≥8 hours of fasting.

Data analysis

In this cohort profile, we summarised baseline sociodemographic characteristics for PLWH and PLWOH and compared proportions between the two groups using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Ideal cardiovascular health (ICVH) metrics or Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) were defined according to the American Heart Association (AHA). This metric includes seven ideal metabolic and lifestyle measures. We determined LS7 using enrolment data, and the LS7 metrics included the following components: blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), diet, fasting glucose, physical activity, smoking and total cholesterol. Each component was categorised as ideal (2 points), intermediate (1 point) and poor (0 points). We then added each individual’s components to obtain an overall score on a scale from 0 (worst) to 14 (best). For each participant, overall cardiovascular health was categorised as ideal (5–7 ideal LS7 components), intermediate (3–4 ideal LS7 components) and poor (≤2 ideal LS7 components).15 16 Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine factors (variables selected a priori) associated with having ICVH metrics, adjusting for sociodemographic and economic variables. All analyses were performed using Stata V.17 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Findings to date

Characteristics of the cohort

Overall, 1100 (600 adults in Zimbabwe and 500 in Zambia) adults have been enrolled in the cohort with a median age of 39 years (IQR 34–46 years). We have enrolled 618 females (56%) and 539 (49%) PLWH (table 2). Median age was similar among PLWH and PLWOH (40 years vs 38 years, p=0.55) but the proportion of women was higher in PLWOH (63% vs 50%, p<0.01). Among PLWH, the median CD4+ cell count was 223 cells/mm3 (IQR 97–411), the median HIV viral load was 24 114 copies/mL (IQR 277–214 271) and 92% initiated an ART regimen including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine and dolutegravir at enrolment. The majority of participants were either in formal or self-employment (68%), with 27% having completed a university degree. In total, 548 (50%) participants lived in high-density suburbs with 317 (29%) having a monthly household income of less than US$20. Monthly income was comparable between the two groups, and most participants were married (62%).

Table 2. Comparison of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, by HIV status.

| Variable | PLWH(N=539) | PLWOH(N=561) | P value |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Country | |||

| Zimbabwe | 303 (56) | 297 (53) | 0.28 |

| Zambia | 236 (44) | 264 (47) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 269 (50) | 349 (62) | |

| Male | 270 (50) | 212 (38) | |

| Age group | <0.001 | ||

| 30–39 | 255 (47) | 309 (55) | |

| 40–49 | 201 (37) | 161 (29) | |

| 50–59 | 63 (12) | 50 (9) | |

| 60–69 | 20 (4) | 30 (5) | |

| 70+ | – | 11 (2) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| Primary | 73 (14) | 124 (22) | |

| Secondary | 279 (52) | 295 (53) | |

| Tertiary | 172 (32) | 123 (22) | |

| No education | 15 (3) | 19 (3) | |

| Area of residence | <0.001 | ||

| Peri urban | 66 (12) | 182 (32) | |

| Low/medium density | 155 (29) | 110 (20) | |

| High density | 302 (56) | 246 (44) | |

| Rural/informal settlement | 16 (3) | 23 (4) | |

| Employment | 0.10 | ||

| Employed | 379 (70) | 368 (66) | |

| Unemployed | 160 (30) | 193 (34) | |

| Monthly household income | 0.09 | ||

| Lowest | 147 (27) | 170 (31) | |

| Middle | 247 (46) | 272 (48) | |

| Highest | 145 (27) | 119 (21) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | ||

| Married | 292 (54) | 388 (69) | |

| Divorced/separated | 118 (22) | 71 (13) | |

| Widowed | 61 (11) | 44 (8) | |

| Single | 68 (13) | 58 (10) |

PLWHpeople living with HIVPLWOHpeople living without HIV

Prevalence of ICVH

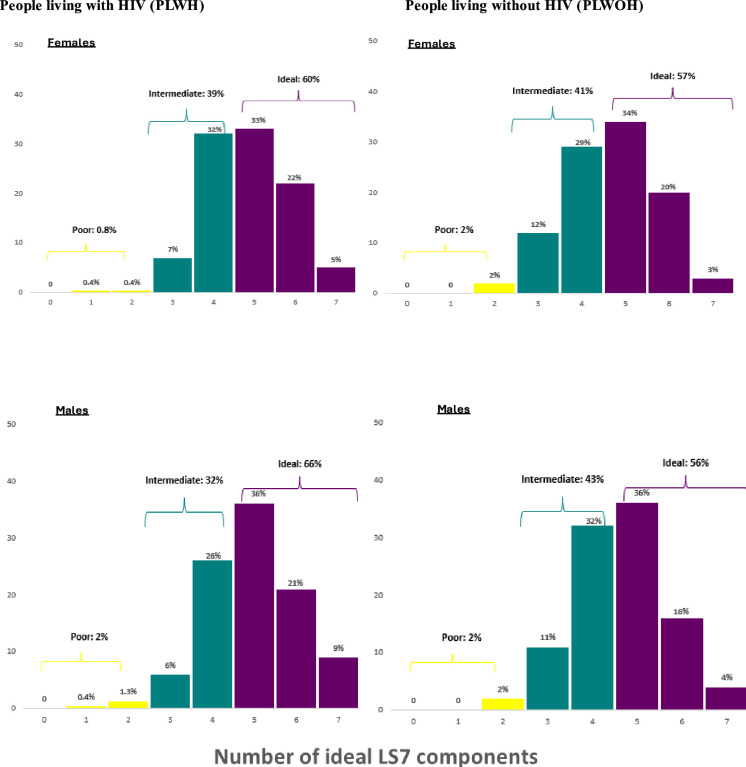

Using the AHA’s ICVH metric (Simple Life 7 score—LS7),17 median ICVH among 1013 participants (93%) with complete data was 11 out of an ideal score of 14 (IQR 10–12, figure 2). The number of participants with ideal overall cardiovascular health (between 5 and 7 ideal LS7 components) was 608 (60%), whereas 389 (38%) had intermediate cardiovascular health and only 16 participants (2%) had poor cardiovascular health. Males living with HIV had the highest proportion with ICVH metrics (66%) whereas women living without HIV had the least number of participants (57%) with ICVH. Overall, 2% of male participants, regardless of HIV status, and 2% of females without HIV had poor ICVH, whilst <1% of females with HIV had poor ICVH (figure 3). Among individual components of the LS7, more females had poor BMI than males, regardless of HIV status (27% vs 3%, p<0.001). The proportion of participants with poor blood pressure was slightly higher among PLWOH when compared with PLWH (33% vs 24%, p=0.007). Physical activity had the most individuals in the ideal category across sex and HIV status groups with an overall 98% of the population meeting ideal physical activity levels. No participants met the criteria for having a poor diet score and, across all groups, over 60% met the intermediate level, with over 15% having ideal diet criteria. The proportion of participants with a poor score for smoking was significantly higher among males when compared with females (26% vs 1%, p<0.001) (figure 4). Overall, untreated HIV (OR: 1.36 (IQR 1.05–1.78)) and being a Zambian participant (OR: 1.81 (IQR 1.31–2.51)) were associated with having ICVH, whereas age older than 50 years (OR: 0.46 (IQR 0.32–0.65)) was associated with not having ICVH metrics (online supplemental S3).

Figure 2. Overall cardiovascular health Life’s Simple 7 (LS7) score among 1013 participants.

Figure 3. Overall ideal cardiovascular health categories based on number of components meeting ideal targets stratified by HIV status and sex. LS7, Life’s Simple 7.

Figure 4. Individual Life’s Simple 7 components by HIV status and sex. BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

Our cohort is designed to provide important findings regarding the burden of HIV and NCDs in a population of adults living with and without HIV in Zambia and Zimbabwe, including some of the first precise estimates of cardiovascular health in Southern Africa. The NCDzz study represents an urban population of adults aged 30 years and older accessing health services at three primary care clinics in Lusaka and Harare. People living with and without HIV come from the same communities and have similar socioeconomic characteristics.

Overall, 60% of the cohort met the criteria for ICVH according to LS7. Our estimates are comparable to most African studies reporting ICVH estimates, with the proportion meeting ideal LS7 scores being 59% in Uganda, 61% in rural Ghana and 53% in rural South Africa.18,20 Differences could be attributed to our relatively young cohort with a median age of 38 years, the inclusion of treatment-naïve PLWH and the ethnic differences in key factors including BMI, diet and physical activity. Estimates from our cohort and other African studies are significantly higher than global estimates of 26% among those younger than 60 years.18 Results from the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) showed that among PLWH with a median age of 51 years, only 9% met the criteria for ideal CVH, and 36% had a poor LS7 score.15 Although these results are not comparable to our HIV population, which was younger and ART-naïve at the time of assessment, we believe our cohort provides an ideal opportunity to evaluate how long-term HIV infection and ART impact cardiovascular and other NCD outcomes.

Although overall LS7 scores were similar in men and women, there were differences in individual ICVH components. For instance, women were significantly more likely to have a poor score for BMI than men, whereas men were significantly more likely to have a poor score for smoking. Our results contrast with most assessments of cardiovascular health among PLWH using traditional CVD risk scores such as Framingham’s risk score, which have consistently predicted poorer CVD outcomes among men.21 Despite the global trend of men traditionally having higher CVD risk, there is a push to increase awareness and prioritisation of CVD research among women as it is the leading cause of death that remains under-recognised.22 High BMI remains a concern among women in our cohort and data strongly suggest this growing problem among women in Southern Africa warranting the need for monitoring CVD outcomes among this group in order to determine the impact of high BMI on clinical endpoints in our settings.23 24

Our results suggest PLWH to have more ICVH metrics, a finding which could be attributed to our study design: many PLWH were assessed prior to ART initiation and had advanced HIV disease as indicated by low CD4+ cell counts. Over 90% of PLWH in our cohort initiated an integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimen, which have been associated with increased metabolic side effects.10 25 It will be necessary to reassess ICVH profiles at subsequent follow-up visits post ART initiation. The cohort will enable further sub-analyses to understand the role of traditional NCD risk factors including smoking, unhealthy diets and physical activity which are areas lacking data from SSA where context-specific considerations on diet and lifestyle factors need to be evaluated.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of NCDzz is the enrolment of PLWOH from the same community as PLWH. Many studies in SSA lack an appropriate control group to draw comparisons between people living with and without HIV. Our cohort also enrolled PLWH at the point of initiating HIV treatment and care, which will allow us to explore the effects of contemporary ART on NCD outcomes. The enrolment of a predominately female cohort provides us with an opportunity to explore the role of sex on cardiovascular and other NCD outcomes. However, as our cohort is a clinic-based study, we lack the true representation of a random community sample, which could better depict the real burden of NCDs in our settings. Our population also lacks the inclusion of participants residing in rural areas, where NCD risk factors and socioeconomic factors may differ greatly from our urban population. The assessment of lifestyle factors including diet and physical activity are prone to bias using current tools, which rely on self-reports. The addition of accelerometry data will assist with the objective measures of activity and will allow a better understanding of the impact of lifestyle factors on NCD risk in our population.26

Future plans

We seek to continue our yearly data collection for an additional 5-year period and expand our work as detailed in the following sections.

Evaluation of end-organ disease

Assessment of incident cardiovascular events will be a critical step for our cohort to determine the changes in CVD and metabolic risk outcomes over time. We plan to include evaluations of end-organ disease including liver, vascular function and cardiac markers during the follow-up period of the study and assess the differences in outcomes by sex and HIV status. We will also assess biomarkers across several timepoints using our stored repository of patient samples.

Inclusion of rural sites

We aim to include a study site in rural Zimbabwe, as part of the study’s long-term follow-up. The addition of this group of participants will enable us to answer questions on the role of the environmental and socioeconomic factors, which could influence the risk for CVD outcomes.

Pilot NCD interventions using advanced methodologies

Leveraging the cohort, we will pilot various interventions including lifestyle and behavioural evidenced-based initiatives for NCD reduction using the trial within cohorts methodologies.

Collaboration

Our cohort data is available through requests made to the IeDEA-Southern Africa Scientific Steering Committee. Interested collaborators including researchers are invited to submit requests to collaborate which are reviewed and considered by the scientific committee. Collaborations can include pooled analyses and expansion of specific scientific aims through sub-studies.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AI069924. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088706).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and study approvals were obtained from the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (UNZABREC, reference no. 011-04-19) and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ, reference no. MRCZ/A/2475). Additional approvals were acquired from the National Health Research Authority in Zambia (NHRA) and Zambia Medical Research Authority (ZAMRA). All study staff were trained on good clinical practice (GCP) and human subject protection (HSP). Patients provided written informed consent to be enrolled and followed in the study for an initial 5 years.

Data availability free text: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Bigna JJ, Noubiap JJ. The rising burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1295–6. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1375–87. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran A, Forouzanfar M, Sampson U, et al. The epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors 2010 Study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;56:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vachiat A, McCutcheon K, Tsabedze N, et al. HIV and Ischemic Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. Cross-sectional Comparison of the Prevalence of Age-Associated Comorbidities and Their Risk Factors Between HIV-Infected and Uninfected Individuals: The AGEhIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1787–97. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enriquez R, Ssekubugu R, Ndyanabo A, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors by HIV status in a population-based cohort in South Central Uganda: a cross-sectional survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25:e25901. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashinya F, Alberts M, Van Geertruyden J-P, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors in people with HIV infection treated with ART in rural South Africa: a cross sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12:42. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekrikpo UE, Akpan EE, Ekott JU, et al. Prevalence and correlates of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease in a Nigerian ART-naive HIV population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019664. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boateng D, Agyemang C, Beune E, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction in sub-Saharan African populations — Comparative analysis of risk algorithms in the RODAM study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;254:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venter WDF, Sokhela S, Simmons B, et al. Dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (ADVANCE): week 96 results from a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e666–76. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agyeman C, Boatemaa S, Frempong G, et al. Obesity in Sub-Saharan Africa. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-12125-3_5-1. http://41.204.63.118:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/49 Available. [DOI]

- 12.NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. The Lancet. 2018;392:1072–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chammartin F, Dao Ostinelli CH, Anastos K, et al. International epidemiology databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa, 2012-2019. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035246. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shamu T, Chimbetete C, Shawarira-Bote S, et al. Outcomes of an HIV cohort after a decade of comprehensive care at Newlands Clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe: TENART cohort. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas PS, Umbleja T, Bloomfield GS, et al. Cardiovascular Risk and Health Among People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Eligible for Primary Prevention: Insights From the REPRIEVE Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:2009–22. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasbani NR, Ligthart S, Brown MR, et al. American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7: Lifestyle Recommendations, Polygenic Risk, and Lifetime Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation. 2022;145:808–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.053730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and Setting National Goals for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reduction. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ketelaar EJ, Vos AG, Godijk NG, et al. Ideal Cardiovascular Health Index and Its Determinants in a Rural South African Population. Glob Heart. 2020;15:76. doi: 10.5334/gh.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magodoro IM, Feng M, North CM, et al. Female sex and cardiovascular disease risk in rural Uganda: a cross-sectional, population-based study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19:96. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Nieuwenhuizen B, Zafarmand MH, Beune E, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health among Ghanaian populations in three European countries and rural and urban Ghana: the RODAM study. Intern Emerg Med . 2018;13:845–56. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1846-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bots SH, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality: a global assessment of the effect of ageing between 1980 and 2010. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000298. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel B, Acevedo M, Appelman Y, et al. The Lancet women and cardiovascular disease Commission: reducing the global burden by 2030. The Lancet. 2021;397:2385–438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00684-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanley S, Moodley D, Naidoo M. Obesity in young South African women living with HIV: A cross-sectional analysis of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chihota BV, Mandiriri A, Shamu T, et al. Metabolic syndrome among treatment-naïve people living with and without HIV in Zambia and Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25:e26047. doi: 10.1002/jia2.26047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venter WDF, Moorhouse M, Sokhela S, et al. Dolutegravir plus Two Different Prodrugs of Tenofovir to Treat HIV. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:803–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chihota BV, Riebensahm C, Muula G, et al. Liver steatosis and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease among HIV-positive and negative adults in urban Zambia. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022;9:e000945. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2022-000945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertens (Los Angel) 2020;38:982–1004. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimala CA, Ngu RC, Kadia BM, et al. Markers of adiposity in HIV/AIDS patients: Agreement between waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, waist-to-height ratio and body mass index. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Diabetes Federation The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. 2006. https://www.idf.org/e-library/consensus-statements/60-idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome.html Available.

- 30.World Health Organization Waist circumference and waist-hip-ration: report of a WHO expert consultation. 2008