1.0. CASE STUDY

Bryan is a 59-year-old man, married with six children, and works as an internet security engineer. He has never been hospitalized prior to this case. Bryan has a history of Type 1 diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and obstructive sleep apnea. On admission to a community hospital, Bryan was found to be in acute respiratory failure and septic shock due to pneumococcal pneumonia. On his third day of hospitalization, Bryan was intubated for worsening respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Three days after intubation, he was transferred to an Awake and Walking intensive care unit (ICU).

This Awake and Walking ICU is a 16-bed medical/surgical ICU in a 262-bed tertiary hospital in the United States (U.S.) Western Mountain Region that operates with a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio. This unit serves as a referral center for a five-state region, receives patients from the hospital’s regional bone marrow transplant unit, and treats a considerable substance use and homeless population. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Awake and Walking ICU was one of the highest acuity ICUs in the state.

For over 20 years, the Awake and Walking ICU has preserved the practice of minimal sedative use after intubation and mobilization within 12 hours of ICU admission. The interdisciplinary team expects patients to be awake, mobile, communicative, autonomous, and connected with their loved ones directly after intubation and throughout their time on mechanical ventilation. Sedative use and bedrest are the exceptions to this unit’s culture. Mobility is used as a clinical intervention to prevent and treat delirium, agitation, and acute respiratory failure. The interdisciplinary team members work with patients to perform their highest level of mobility three times a day. Embedded in the culture of this Awake and Walking ICU, each interdisciplinary team member understands and fulfills their role in delirium, pain, sedation, and mobility management. Table 1 details the definition and characteristics of both the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU.1,2

The Table 1.

Definition and components of the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU*

| ABCDEF Bundle | |

|---|---|

| Definition: | The goal of the ABCDEF bundle is to help patients become more alert, mentally engaged, and physically active. It aims to empower patients and enable them to express their unmet physical, emotional, and spiritual needs. A bundle is a package of evidence-based practices intended to be delivered as a whole every day. |

| Components: |

Assess, prevent, and manage pain Both spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing trials Choice of analgesia and sedation (e.g., avoid benzodiazepines) Delirium: Assess, prevent, and manage Early exercise and mobility Family engagement and empowerment |

| Awake and Walking ICU | |

| Definition: | In the Awake and Walking ICU the goal of care is to partner with patients to achieve and maintain the highest level of cognitive function (e.g., awareness) and mobility (e.g., walking) from the point of ICU admission to discharge. The Awake and Walking ICU is 100% ABCDEF bundle compliance. |

| Characterized by: |

|

Both the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU incorporate best practices from the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU (i.e., PADIS Guidelines).

The Table 2 case study illustrates how the ABCDEF bundle in an Awake and Walking ICU prevents delirium and ICU-acquired weakness and, therefore, prevents Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS). The table displays Bryan’s care with 100% compliance with the ABCDEF bundle in the Awake and Walking ICU (green column), <50% compliance with the ABCDEF bundle (yellow column), and care without a bundled approach (red column). The <50% ABCDEF bundle compliance column is theoretical, with timing and interventions extrapolated by Treatment of Mechanically Ventilated Adults with Early Activity and Mobilization (TEAM) study protocols to inform care progression.3 The care without a standardized bundle is also theoretical, with care progression informed by protocols from a 2008 early mobility study.4 The details of Bryan’s condition and treatments were extracted from his health record and are used to guide the reader through his critical illness journey.

Table 2.

Case study detailing three protocols of care

| Standard of Care (Theoretical case; ABCDEF bundle not protocolized) |

ABCDEF Bundle Care (Theoretical case; <50% ABCDEF bundle compliance) |

Awake and Walking ICU Care (Actual case; 100% ABCDEF bundle compliance) |

|---|---|---|

|

Day 0–2 ventilator settings: PRVC Assist/Control, PEEP 10 cmH2O, FiO2 0.7 Actual Case: Bryan was awake after intubation without sedatives and on a norepinephrine infusion. He communicated his needs with a pen and paper and was standing and marching in-place at the bedside hours after intubation. He stayed informed of his condition and continuously communicated with his wife. | ||

|

Sedative: Continuous infusion (midazolam) RASS −3 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −3 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Day 1 stood at the bedside and marched in place. Day 2 walked 200 feet. Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 3 ventilator settings: PRVC Assist/Control, PEEP 12 cmH2O, FiO2 0.7 Actual Case: Bryan was transferred to a higher acuity AWICU for worsening ARDS. His wife and children remained at his bedside day and night. | ||

|

Sedative: Continuous infusion (midazolam) RASS: −3 Mobility: Passive ROM Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −3 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Sat edge of bed for 20 min × 2, sat in the chair during the day. Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 4 ventilator settings: PRVC Assist/Control, PEEP 12 cmH2O, FiO2 0.8 Actual Case: Bryan preferred to sit up in the chair during the day to ease the work of breathing. He was able to provide feedback to his respiratory therapist to adjust ventilator settings for his comfort. He complained of thirst and found that ice water flushes down the feeding tube eased his discomfort. | ||

|

Sedative: Continuous infusion (midazolam) RASS: −3 Mobility: Passive ROM Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −3 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Walked 400 ft × 3 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 5 ventilator settings: PRVC Assist/Control, PEEP 18 cmH2O, FiO2 1.0 Actual Case: Bryan became unable to oxygenate with movement. The care team discussed with him the option and indication for pronation, sedatives, and paralysis. Bryan consulted with his wife and decided to proceed with pronation, sedatives, and paralysis. | ||

|

Sedative: Continuous infusion (midazolam) RASS: −5 Mobility: Passive ROM Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −5 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Walked 400 ft × 1 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Days 6–7 ventilator settings: Assist/Control, PEEP 20 cmH2O, FiO2 0.8 Actual Case: Bryan remained prone, sedated, and paralyzed for 48 hours. His brother and sister stayed with him the entire time. | ||

|

Sedative: Continuous infusion (midazolam) RASS: −5 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −5 Mobility: None Communication: None |

Sedative: Continuous infusion (propofol and fentanyl) RASS: −5 Mobility: None Communication: None |

|

Days 8–13 ventilator settings: PEEP ranged 8–16 cmH2O, FiO2 ranged 0.4–0.5 Actual Case: Bryan was able to tolerate being supine and a sedative interruption was performed. When it was noted that he was able to oxygenate with movement, sedatives were discontinued. He continued to communicate and mobilize. He watched western moves with his brother. | ||

|

Day 9: Assist/Control Sedative: Continuous infusion RASS: −3 Mobility: Bed-level mobility Communication: None |

Day 9: Failed CPAP trial Sedative: Continuous infusion with interruption for mobility RASS: −3 Mobility: Bed-level mobility Communication: Mouthing words and head-nods (too weak to write) |

Day 9: Assist/Control Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Walked 200 ft × 3 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 11: Assist/Control Sedative: Continuous infusion with interruption for mobility RASS: −3 Mobility: Bed-level mobility Communication: None |

Day 11: Failed CPAP trial Sedative: Continuous infusion with interruption for mobility RASS: −2 Mobility: Sat edge of bed for 15 minutes Communication: Mouthing words, head-nods, point to words |

Day 11: Assist/Control Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Walked 1,000 ft × 2 and 1,200 ft × 1 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 12: Failed CPAP trial Sedative: Continuous infusion with interruption for mobility RASS: −2 Mobility: Bed-level mobility Communication: None |

Day 12: Failed CPAP trial **Tracheostomy placed** Sedative: Discontinued RASS: −1 Mobility: Standing with tilt table Communication: Mouthing words, head-nods, point to words |

Day 12: Assist/Control Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: 1,800 ft × 1 and 1,500 ft × 2 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 13: Failed CPAP trial Sedative: Continuous infusion with interruption for mobility RASS: −2 Mobility: Bed-level mobility Communication: None Plan: Tracheostomy |

Day 13: Passed CPAP trial Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: Standing with tilt table Communication: Mouthing words, head-nods, point to words Plan: Trial trach collar, order speech language pathology consultation to prepare for speaking valve, prepare for inpatient rehab transfer |

Day 13: Assist/Control Sedative: None RASS: 0 Mobility: 2,000ft × 3 Communication: Writing on a clipboard, interacting with his wife. |

|

Day 14: Extubated Actual Case: Bryan was able to eat on day 15. He was transferred out of ICU on day 18 and discharged to home on day 21. Before hospital discharge, he walked the stairs and scored a 28/30 on his Montreal Cognitive Assessment. He returned to work 2 months after discharge without cognitive, physical function, or psychological impairments. He was on supplemental oxygen and had some ongoing shortness of breath but resumed hiking, hunting, fishing, home renovations, and stargazing shortly after discharge. | ||

Abbreviations: cmH2O = centimeters of water, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, FiO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen, PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure, PRVC = pressure-regulated volume control, RASS = Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale

2.0. INTRODUCTION

Advancements in critical care medicine have resulted in more patients surviving critical illness.5 With over 5 million patients admitted to ICUs in the U.S. annually, there is a growing number of critical illness survivors living with the long-term sequelae of PICS.5,6 PICS is the new or worsening physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial impairments following critical illness that persist beyond hospitalization, affecting up to 70% of survivors.7 Physical impairments include neuromuscular and musculoskeletal deficiencies that can result in deficits with swallowing, coordination, ventilatory capacity, mobility, and ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs).8 Cognitive impairments can range from subtle declines in memory, deficits with attention, problem-solving, information processing and executive functioning, to dementia, all of which can impact a person’s ability to perform functional tasks and navigate social dynamics, diminishing their quality of life.8 Depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety are examples of psychosocial impairments.8 Furthermore, family members and caregivers can also suffer from PICS, termed PICS-Family, in which they experience depression, PTSD, anxiety, and prolonged grief.9

There is a dynamic interrelationship between critical illness, critical care practices, and PICS. ICU patients with delirium, which is exacerbated by factors like benzodiazepine use, immobility, restraints, and deep sedation, have a higher prevalence of long-term cognitive impairment, but mobilization within 48 hours of intubation can decrease delirium and improve cognitive function after discharge.10–12 Protocols like the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU (Table 1) directly address critical care practices that can mitigate the prevalence and severity of PICS.13 Thus, Bryan’s treatment of being promptly awake, unrestrained, and walking during mechanical ventilation served to protect him from PICS by shifting focus from rehabilitative to prehabilitative care (i.e., building patient resilience to tolerate the imposed immobility endured during hospitalization).14

Meta-analyses examining the long-term effects of these interdisciplinary approaches have reported either weak or inconclusive evidence.15–17 Our objective is to synthesize the literature on the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU and their relationship to mitigating PICS. We also describe the role of humanizing critical care, creating an environment and culture that facilitates adoption and adaptations for diverse settings, and implementation strategies. Our vision is to promote ICU practice patterns that support patient autonomy and their ability to participate in care without the burden of sedatives, delirium, and immobility. Since each ICU has unique barriers and facilitators to adopting these care approaches, we focus on discussing the broader picture of what tools, processes, and strategies are needed to realize our vision of liberation. Lastly, we provide recommendations for research and quality improvement.

3.0. A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The development of the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU occurred over several decades. In the 1970’s, intubated patients were often awake and walking. The 1990’s was an era of experimentation with ventilator settings involving high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and 12ml/kg tidal volumes.18 To address the discomfort and dyssynchrony from those settings, healthcare providers started using high doses of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioids, and paralytics for extended periods during mechanical ventilation. The adverse effects of sedatives were unknown at the time. The belief that patients were “sleeping” while sedated resonated with clinicians who were eager to protect patients from discomfort and psychological trauma.19 While these patients tolerated high ventilator settings and survived critical illness, mechanical ventilation and hospitalization days were prolonged, and cognitive, psychological, and physical impairments ensued.

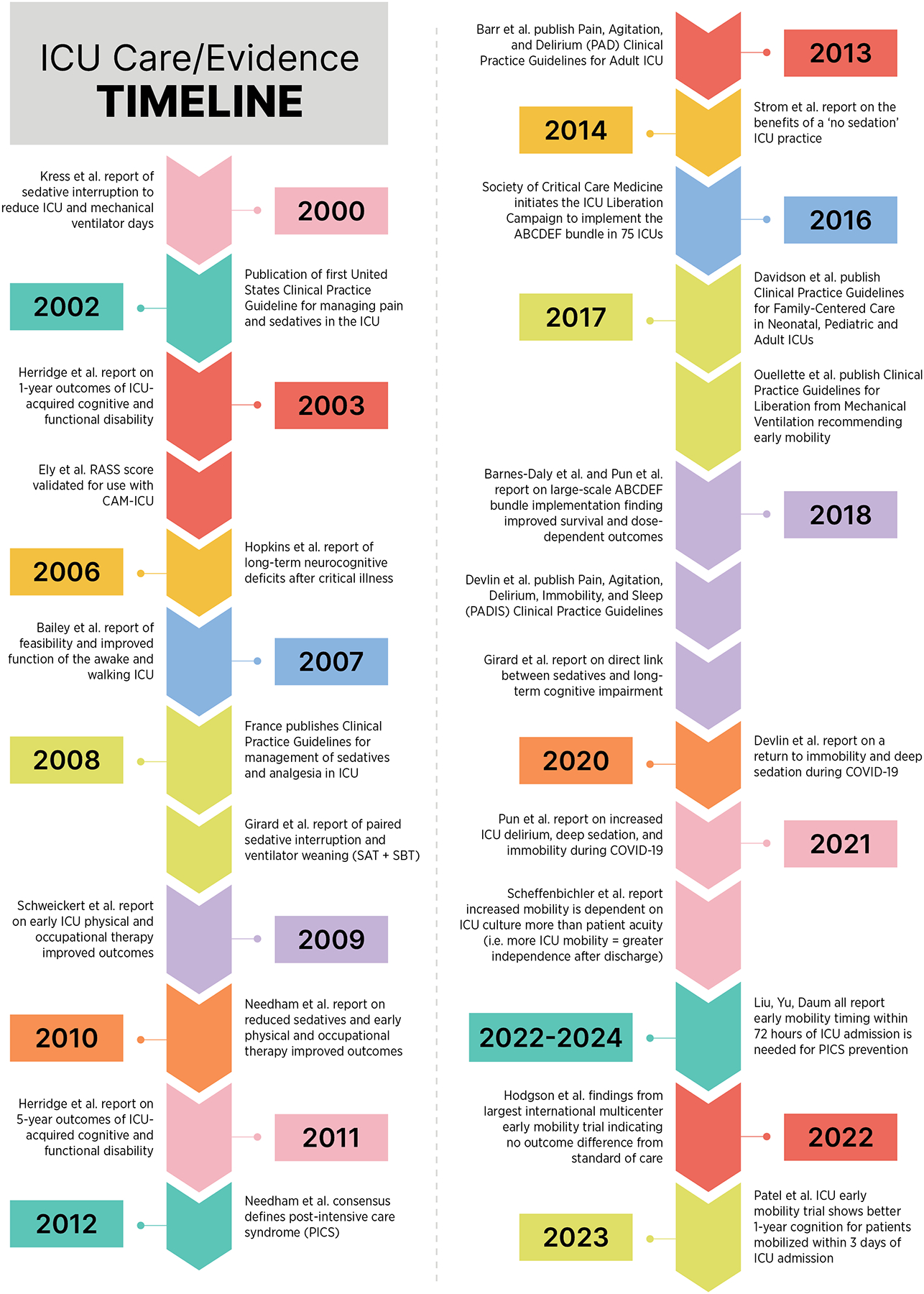

A landmark study in 2003 reported persistent functional disability one year after ICU discharge in ARDS survivors, which continued five years later.20,21 These findings, along with newly published clinical practice guidelines to treat pain before sedating patients, informed a series of seminal studies over the last 25 years.22 The resulting knowledge laid the foundation for the current emphasis on pain and symptom management, sedative minimization, delirium assessment and management, and early mobility in critically ill patients (illustrated in Figure 1). Evidence generated from these studies led to the development, refinement, and dissemination of the ABCDEF bundle.13 The bundle aims to improve ICU patient cognition and reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation by addressing pain, sedative use, delirium, and mobility.

Figure 1.

The Timeline of Evidence Supporting the Awake and Walking Intensive Care Unit

In 2014, a Spanish team of physicians posed a blog question asking “how would you like the Intensive Care Unit to be?” There were over 10,000 responses which, overall, reflected healthcare professionals’ rising concerns about the degradation of patient dignity and autonomy in the ICU. As a result, the Humanization of the Intensive Care movement began (Proyecto HU-CI).23 The movement sought to shift ICU care toward a human-centered approach that focuses on the patient (individualized care), family, and the healthcare professional. A human-centered approach aligns with both the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU, as both aim to optimize ICU care to prevent PICS. However, the culture of sedative use and immobility persists. The adoption of the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU into routine care has been arduous, and ABCDEF bundle performance declined during the COVID-19 pandemic.24–27 Nonetheless, the quest for human-centered care to proactively address symptoms, minimize sedative use, optimize mobility, and prevent PICS in the ICU continues.28

4.0. SUPPORTING EVIDENCE

The case of Bryan, who received early mobility and rehabilitation during Awake and Walking ICU care, demonstrates the potential benefits of this approach. By being free of sedation, allowed to walk, and engage in his care, Bryan was able to preserve physical and cognitive function, avoid long-term consequences of critical illness, and successfully return to work just two months after discharge, in contrast to most ICU survivors who are unable to do so. What follows is a review of supporting evidence for the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU.

ABCDEF Bundle Care

The widely accepted practice to mitigate the prevalence of PICS involves early timed patient awakening, delirium assessment/prevention/management, mobility, and family engagement. These recommendations come from clinical practice guidelines29 and were translated into practice through the ICU Liberation Campaign using the ABCDEF bundle. In a prospective quality improvement collaborative of 68 academic, community, and federal ICUs, performance of the complete ABCDEF bundle was associated with a lower likelihood of 7-day mortality, next-day mechanical ventilation, coma, delirium, physical restraint use, ICU readmission, and discharge to a facility other than home.2 The results also indicated dose-response effects of ABCDEF bundle performance, with higher proportional performance resulting in greater improvement in each clinical outcome (p<0.002).

The benefits of the ABCDEF bundle were observed in another quality improvement project that evaluated the performance and sustainability of the ABCDEF bundle with both mechanically ventilated and non-mechanically ventilated patients across 11 adult ICUs at six community hospitals. The implementation of the ABCDEF bundle resulted in a 0.5-day reduction in the average ICU length of stay, a 0.6-day decrease in the average duration of mechanical ventilation (p=0.01), and an 18% decrease in the proportion of ICU stays lasting seven days or more (p<0.01).30 Importantly, there was another dose-response relationship equating to a 15% improvement in survival for every 10% increase in bundle compliance.30 These real-world findings illustrate the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU (i.e., units where ABCDEF bundle is 100% compliant) approaches can enhance long-term patient outcomes by addressing upstream risk factors for future development of PICS (e.g., sedative use, delirium, immobility). A meta-analysis evaluating the effect of the ABCDEF bundle on delirium, functional outcomes, and quality of life in critically ill patients found a reduction in delirium after implementation.17 However, a recent randomized controlled trial found that early mobilization after interruption of sedation within 48 hours of intubation resulted in a 44% reduction in cognitive impairment, fewer cases of ICU-acquired weakness, and higher quality of life scores in the physical domain at one-year follow-up compared to usual care.31

Awake and Walking ICU Care

Numerous studies have examined the impact of early mobility in ICU care. Three recent meta-analyses examining the impact of early mobility on short and long-term outcomes conclude the dose and timing of an early mobility intervention contribute to differences between study groups.32–34 One concluded that early mobilization within 24–72 hours of ICU admission or the initiation of mechanical ventilation could curtail the incidence of ICU-acquired weakness and preserve muscle strength, while early mobilization within 24–48 hours could reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay.34 These findings support the Awake and Walking ICU as mobility is initiated upon ICU admission (timing) at their highest level of mobility (dose). Further, a recent retrospective study identified that each additional 10 minutes of early mobility resulted in greater improvement in functional outcomes and hospital length of stay.35

The dose-dependent relationship between early physical rehabilitation and long-term critical illness recovery was tested in the largest population-based ICU early mobility trial to date (TEAM trial).3 The study included 750 patients at 49 hospitals in six countries and employed 1:1 randomization to an early mobilization with sedative minimization and daily physiotherapy or usual care (i.e., the level of mobilization normally provided in each ICU) group. For both groups, early mobility was initiated at a median of 60 hours post-ICU admission. Patients scored a median Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) score of −3 (i.e., minimal response to verbal stimulation) at randomization. Sedative infusions were to be adjusted to a RASS −2 to +3. The main barriers to mobility were sedation and agitation. Despite the intervention group engaging an average of 20 minutes of the highest-level mobility achievable with trained physical therapists compared to 8 minutes with the usual care group, the intervention group did not demonstrate improved outcomes.3 The lack of benefit may have been due to the relatively delayed timing of out-of-bed mobility initiation (5.5–6.5 days after ICU admission) and protocolized sedative use, suggesting that mobility interventions alone are insufficient without addressing sedative use and other barriers to activity within the complex ICU environment.

In 2010, a landmark single-center trial demonstrated the benefits of a no sedative protocol for mechanically ventilated patients.36 Patients in the intervention group were awake (RASS −1.3 to 0.8; i.e., sustained eye opening to verbal stimulation) and received morphine bolus for pain management, while control group patients received sedatives (RASS −2.3 to −1.8; i.e., nonsustained eye opening to verbal stimulation). The no-sedation approach significantly reduced ventilator and ICU days and facilitated patients’ ability for participation, social interaction, decision-making, and rehabilitation without increasing 90-day mortality, PTSD, anxiety, or depression.37,38

Bryan’s testimony affirms some of the benefits of his Awake and Walking ICU experience: “I was able to make friends with some of the staff and understand their concern for me. That helped me push harder to do the physical therapy, and to overcome the challenges that I faced. I am thankful that it was handled the way it was. I can look back at it now, and not have a period of my life missing. Even though it was a difficult period, I am still thankful for the memory of it.”

5.0. HUMANIZATION: AN ESSENTIAL FEATURE OF ABCDEF BUNDLE AND AWAKE AND WALKING ICU

By fully implementing the ABCDEF bundle in the AWAKE AND WALKING ICU, Bryan’s critical illness journey was humanized, allowing him to remain awake and engaged with his caregivers and family. This preserved his cognitive and motor function to write and communicate, enabled him to participate actively in his care, and provided his care team with valuable insights into his personality, humor, and resilience beyond just his medical diagnosis.

Humanizing the ICU experience goes beyond just avoiding sedative use. It requires incorporating elements that address the individual’s physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.39 This includes understanding the patient and family’s personality, values, beliefs, cultural context, and environment. The same is also true in reference to clinicians. Humanization involves treating all individuals in the ICU, including patients, families, and clinicians, with respect, dignity, and empathy, and is a central component of the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU paradigms.40

Communication is a key aspect of humanization in the ICU and includes not only verbal and auditory components, but also non-verbal elements like proximity, posture, eye contact, and touch which significantly impact how patients and families perceive information.40 Employing empathetic, respectful, and personalized communication strategies, as well as understanding patients’ preferred communication styles, can help ensure a humanized approach. To address communication barriers due to sedatives, language differences, and cognitive/sensory deficits, a range of low-tech (e.g., visual aids, communication boards) and high-tech (e.g., patient communicator apps) solutions can profoundly impact care delivery.41 By providing patients with communication tools, the health care team can better assess needs, enabling personalized care to manage symptoms and avoid sedative use.28 Other humanizing strategies including short trips outside the room, use of rocking chairs, aroma therapy, meditation, animal-assisted therapy, music, and visiting with loved ones, can positively impact overall patient well-being and their functional outcomes.42,43

Bryan’s perspective further emphasizes the important role of communication for humanization: “I was initially worried about being awake on the ventilator. When I realized that I could still communicate with everyone, it made sense to me. It allowed me to tell the staff how I was really feeling, and what was bothering me instead of them just guessing. It allowed me to communicate with my family and gave me the chance to tell them that everything was going to be okay when I could see the worry in their eyes. Having the ability to communicate helped me remember the experience even though it was not necessarily a pleasant one. It helped me stay connected from day to day with what was going on, which helped me keep things straight in my head. That helped with my recovery later on at home.”

6.0. CREATING THE CULTURE FOR ABCDEF BUNDLE AND AWAKE AND WALKING ICU SUCCESS

To prevent PICS, critical care teams should develop an ICU culture that focuses on applying the ABCDEF bundle in an Awake and Walking ICU approach to address sedative use, delirium, sleep, and early mobility holistically. The coordinated efforts of Bryan’s critical care team, who recognized the risks of sedative use and treated delirium as a medical emergency, allowed him to remain awake and mobile immediately and throughout his ICU stay. This team-based approach viewed mechanical ventilation as a tool to facilitate mobility, not a barrier, and considered the short and long-term impacts of interventions; thus, resulting in Bryan being awake, communicative, and autonomous with few exceptions. This patient-centered, mobility-focused approach reflects a shared responsibility across all disciplines to support and empower patients throughout their recovery.

Culture as a Determinant of ICU Practices

Culture is defined as a set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an organization and shape the behavior of its members.44 It influences how people interact with one another, make decisions, and perform tasks. It is also closely linked to abstract causal models organization members share.45 For example, if ICU members share the idea that “early mobilization improves patient outcomes,” early mobility is more likely to be accepted and prioritized when caring for patients. The culture of safety and interprofessional collaboration is key to delivering the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU care.46 Since the ICU is a complex environment composed of diverse healthcare professionals (e.g., training, expertise, knowledge, experience, attitudes), having well-aligned visions and goals for patient care is crucial. If core beliefs and attitudes are misaligned among team members, it may become a source of disagreement, tension, and ineffective teamwork, leading to poor patient outcomes. Each member of an organization has the potential to influence organizational culture with appropriate tools, processes, and strategies. Behavioral science provides insights into how we can engineer the environment, introduce new narratives, and change organizational culture.

The State of ICU Culture

The current state of ICU culture largely reveals a concerning reliance on sedative overuse. In recent studies, more than half of patients are minimally responsive or comatose during the first 1–3 days of mechanical ventilation, with 97% receiving continuous sedative infusions.3,47 This ingrained practice is further reinforced by the belief among most ICU healthcare professionals that sedatives are helpful, compassionate, and necessary for patient comfort.48–50 However, this cultural norm fails to acknowledge the well-documented adverse effects of sedatives on delirium, mobility, and sleep.51 In ICUs that adopt a more patient-centered, minimal-sedative approach, intubated patients are often awake and alert, with sedative use as the exception rather than the norm.

The ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU models recognize the interlinked nature of sedative use, mobility, delirium, and sleep (Figure 2), and the Awake and Walking ICU model, specifically, leverages active mobilization as a multifaceted therapeutic intervention to address these factors holistically.1,51 In contrast, the misconception of sedative interruption solely as a precursor to extubation or neurological exams has led to the resumption of continuous sedative infusions when breathing trials fail or the neurologic exam is complete, perpetuating sedative overuse.52,53 The cultural practice of brief sedation vacations, holidays, and interruptions creates a barrier to practicing true sedative cessation. Altogether, the available data suggests that a cultural shift is needed in many ICUs to move away from the default use of continuous sedative infusions and toward a more patient-centered, mobility-focused approach that prioritizes avoiding the adverse effects of sedatives and prompt mobilization.

Figure 2.

The Interlinked Nature and Continuum of Critical Care and Its Effect on Outcomes

Engineering an ICU Culture Toward the Awake and Walking ICU

To further understand the determinants of sedative practices, we must also take the systems approach and examine the organizational policies, processes, and climate that promote or prevent the implementation of evidence-based practices. For example, how would designating patient falls and self-extubation as never events incentivize the behaviors of bedside clinicians making decisions on sedation, restraints, and mobility? Or would it create a risk-averse culture? Would knowing that prolonged bedrest, oversedation, and restraint use could raise the risk of future falls, delirium, and self-extubation change care prioritization? How does prioritizing compliance (e.g., checklist use in the medical record) instead of prioritizing patient interaction (e.g., communication, mobility) influence practice? In the current healthcare system, where concepts like patient-centered care and value-based care are admired but not reinforced, systems can prevent individual, well-intentioned clinicians from providing the best care possible.

7.0. KEY CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

For Bryan, the Awake and Walking ICU interdisciplinary team’s commitment to 100% ABCDEF bundle care, along with their shared goal and collaborative effort, contributed to the successful implementation of the Awake and Walking ICU approach. Next, we outline strategies to foster a shared vision and common goal among the interdisciplinary team, which is crucial for the successful operationalization of evidence-based practices like the ABCDEF bundle in the ICU.

Barriers to implementing the ABCDEF bundle have been extensively studied, with limited data on implementing the Awake and Walking ICU approach. Analyzing these barriers through the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) reveals four domains influencing implementation: patient-related (CFIR outer setting), clinician-related (CFIR characteristics of individuals), protocol-related (CFIR intervention characteristics), and ICU contextual barriers (CFIR inner setting).25 The most frequently identified barriers include clinician-related factors like knowledge, self-efficacy, and attitudes, as well as ICU context factors like interprofessional team coordination, staffing, and turnover.25 Addressing these barriers is crucial when selecting and operationalizing implementation strategies - the approaches or techniques used to enhance adoption, implementation, sustainability, and spread of an innovation (e.g., ABCDEF or Awake and Walking ICU). For example, in the ICU Liberation collaborative, 63 out of 73 Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) implementation strategies were employed to enhance ABCDEF bundle adoption.54 There were clear differences in the perceived helpfulness and feasibility of the most highly used strategies (e.g., train and educate stakeholders) across sites, potentially indicating the high feasibility but minimal helpfulness of education strategies. Despite the high number of strategies implemented, less than half of the strategies were tailored to each site’s unique ICU context. This lack of tailored implementation strategies likely contributed to low overall bundle compliance during this 68-site quality improvement collaborative, as strategies typically didn’t target context-specific behaviors and limited their effectiveness.

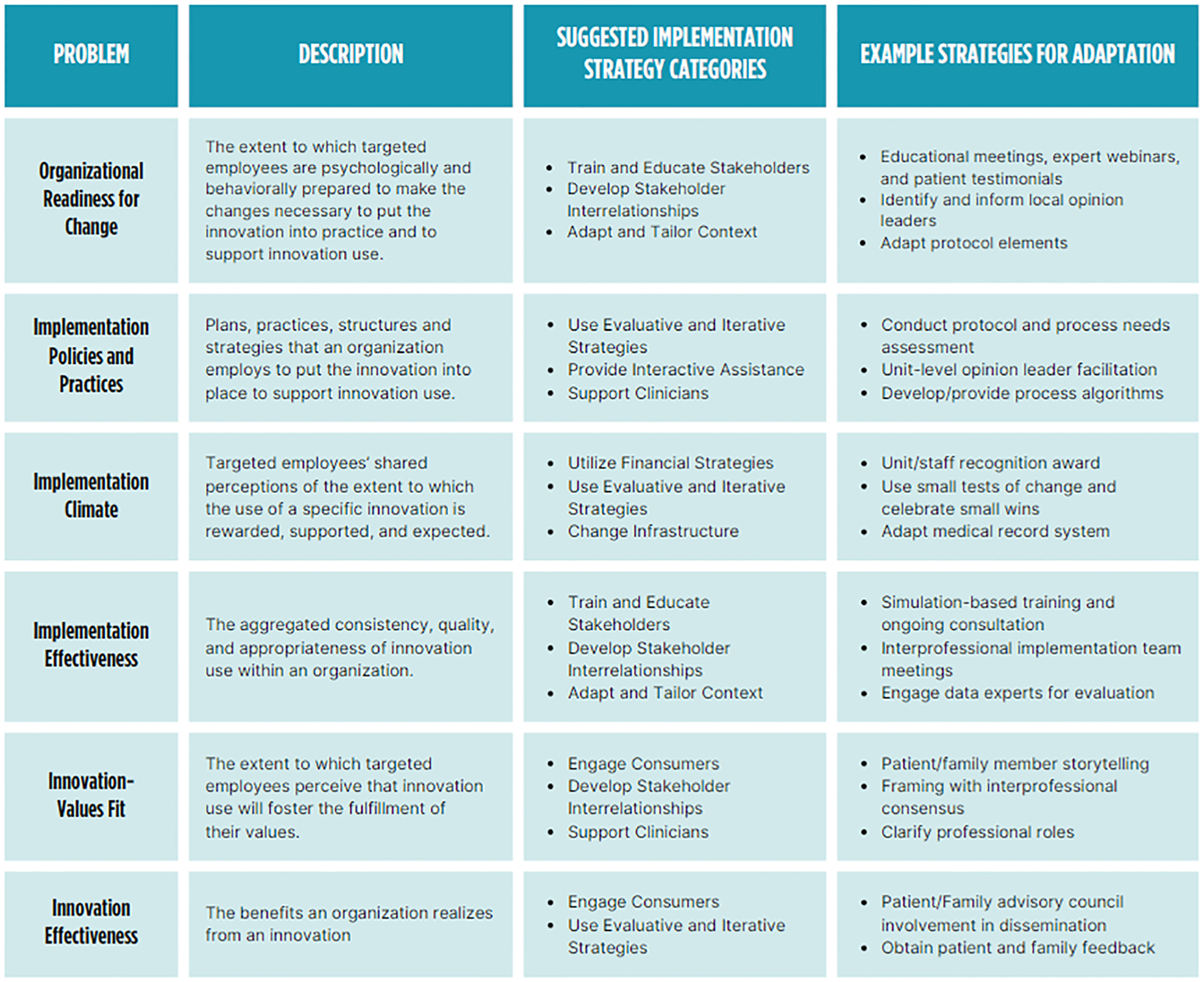

Interdisciplinary teamwork is a consistent facilitator in studies implementing processes like the Awake and Walking ICU, where an interdisciplinary team approach is consistently operationalized in clinical practice. The significance of interprofessional teamwork, safety culture, and a collaborative work environment has also been well-documented in the context of ABCDEF bundle implementation.46,55–57 Aligning the visions and goals of interdisciplinary team members is crucial in complex adaptive healthcare systems where various semi-autonomous agents interact dynamically.58–60 The Organizational Theory of Innovation Implementation Effectiveness provides a useful conceptual framework building the ICU context necessary for success.61,62 The theory posits the success of innovation implementation depends on the foundational organizational culture, climate, and readiness for change. Previous studies employing strategies consistent with this framework have shown successful implementation of sedation minimization and early mobilization practices.63–65 For instance, an ICU rehabilitation quality improvement project utilized the 4 Es model (Engage, Educate, Execute, and Evaluate). This included: 1) storytelling to set the stage for change (organizational culture and climate), 2) education and training to enhance commitment and collective efficacy among ICU team members for necessary changes (readiness for change), 3) execution of a standard mobilization algorithm (implementation policies and practices), and 4) weekly multidisciplinary program evaluations to promote a culture of early rehabilitation in the ICU (implementation effectiveness, innovation-values fit, and innovation effectiveness).66 Figure 3 defines these domains, identifies corresponding implementation strategy categories, and provides example strategies.

Figure 3.

Implementation Strategies and Adaptations to Enhance Adoption of the Awake and Walking Intensive Care Unit

The problem and descriptions are informed by the Organizational Theory of Innovation Implementation Effectiveness. The suggested implementation strategy categories are informed by the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) implementation strategy compilation.

When designing practice change interventions using any of the existing models and frameworks, it’s also important for implementers to consider integrating insights from behavioral and agile sciences.67 The MINDSPACE checklist is another way to evaluate whether your planned interventions align with some of the common and influential cognitive biases.68 Examples of such interventions include webinars explaining the benefits of early mobilization by experts (messenger [M]), recognition of bedside clinical champions and exemplars (incentives [I]), publicly celebrating small wins (norm [N]), changing the default sedative order set to ‘as needed’ administration instead of continuous infusion (default [D]), patient stories that describe subjective experiences of coma and delirium (salience [S]), ICU rounding checklist that includes early mobilization (priming [P]), inviting ICU survivors to share their joys and struggles (affect [A]), audit and feedback (commitments [C]), and positive feedback of desirable outcomes (ego [E]). These environmental cues or nudges can steer people’s behaviors without taking away their freedom of choice. Nudges are increasingly studied and applied in healthcare to promote healthier behaviors among patients and to assist healthcare professionals in making clinical decisions that are more likely to benefit patients. Behavioral interventions like the examples above may be helpful in fostering the organizational culture, climate, and readiness for change that support the establishment of the ABCDEF bundle and ultimately, the AWAKE AND WALKING ICU.

8.0. CONCLUSION

The evolution of critical care from sedative-centric approaches to the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU emphasizes the importance of interprofessional teamwork and patient-centered care. With a focus on keeping patients awake, facilitating mobilization for better post-discharge functioning, and promoting patient participation, the Awake and Walking ICU aims to mitigate the long-term effects of sedative use and immobilization. However, successful implementation of the ABCDEF bundle and the Awake and Walking ICU requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses cultural and attitudinal shifts among clinicians, as well as teamwork at various levels of care.

Bryan’s successful discharge from the ICU and return to his baseline quality of life following receipt of the full ABCDEF bundle in the Awake and Walking ICU underscores the importance of human-centric symptom management and early mobilization in critical care. Our observations suggest that defaulting to deep sedation without considering individual patient needs may contribute to adverse outcomes such as ICU-acquired weakness and PICS. While literature supporting the ABCDEF bundle’s efficacy continues to grow, further investigation of its mastery in the Awake and Walking ICU is warranted to fully evaluate the benefits.

KEY POINTS.

Sedation and immobility are modifiable risk factors for post-intensive care syndrome.

Mobility in an Awake and Walking ICU is considered a prompt life-saving intervention used to prevent and treat delirium, agitation, and acute respiratory failure.

The ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU promote patient wakefulness, cognition, and mobility to mitigate long-term consequences of critical illness (i.e., post-intensive care syndrome) affecting up to 70% of survivors.

These approaches can enhance long-term outcomes by addressing risk factors like sedative use, delirium, and immobility, though the strength of evidence varies.

Successful implementation requires creating an ICU culture focused on minimizing sedatives, enabling early mobility, and overcoming organizational barriers through tailored strategies.

SYNOPSIS.

The ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU approach aim to prevent the long-term consequences of critical illness (i.e., Post-Intensive Care Syndrome) by promoting patient wakefulness, cognition, and mobility. Evidence shows these approaches can improve outcomes by addressing sedative use, delirium, and immobility. Humanizing the ICU experience is key, preserving patients’ function and autonomy. Successful implementation requires cultivating an ICU culture focused on avoiding sedatives and initiating prompt mobilization, addressing organizational barriers through tailored strategies. Overall, these patient-centered, mobility-focused models offer a holistic solution to the complex challenge of preventing post-intensive care syndrome and supporting critical illness survivors.

Clinics Care Points.

Implement the ABCDEF bundle and Awake and Walking ICU to improve short- and long-term outcomes.

Minimize sedative use in mechanically ventilated patients to prevent long-term cognitive impairment, as sedation is associated with higher prevalence of delirium and immobility.

Initiate early mobility interventions within 48 hours of intubation to decrease delirium and improve cognitive function after discharge, recognizing the dose-response relationship between early mobilization and improved clinical outcomes.

Cultivate an ICU culture that prioritizes patient wakefulness, cognition, and mobility, and views mechanical ventilation as a tool to facilitate mobility rather than a barrier.

Avoid the pitfalls of sedative interruptions without a plan for sedative cessation, as these can perpetuate sedative overuse and hinder patient mobility and recovery.

Acknowledgement:

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institutes of Health or author institutions.

DISCLOSURES:

KD is the owner of Dayton ICU Consulting.

HL received grant funding from National Institutes of Health NIA (1K23AG076662-02).

HJE served as consultant for Arjo-Huntleigh and served as speaker for American Physical Therapy Association.

MF is supported by a mentored research training grant from the National Institute of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32GM135169).

PG is a salaried (non-sales/commission based) clinical educator and product specialist for VitalGo Systems.

LMB received grant funding from National Institutes of Health NIA (R01AG077644 and R42AG080891).

Contributor Information

Kali Dayton, ICU Sedation and Mobility Consultant, Dayton ICU Consulting, Washington, USA.

Heidi Lindroth, Department of Nursing, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; Nurse Scientist, Center for Innovation and Implementation Science and the Center for Aging Research, Regenstrief Institute, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Heidi J. Engel, Physical Therapy ICU Clinical Specialist, University of California San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF), San Francisco, CA USA.

Mikita Fuchita, Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA.

Phillip Gonzalez, Occupational Therapist/Clinical Specialist, VitalGo Systems, Mirimar, FL USA.

Peter Nydahl, Nursing Research, University Hospital of Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel, GERMANY; Institute of Nursing Science and Development, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, AUSTRIA.

Joanna L. Stollings, Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Department of Pharmaceutical Services, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA; Investigator, Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Leanne M. Boehm, Assistant Professor, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Nashville, TN USA; Investigator, Critical Illness, Brain dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) Center at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dayton K, Hudson M, Lindroth H. Stopping Delirium Using the Awake-and-Walking Intensive Care Unit Approach: True Mastery of Critical Thinking and the ABCDEF Bundle. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2023;34(4):359–366. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2023159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU liberation collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(1):3–14. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Investigators TS, Group tACT. Early active mobilization during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;387(19):1747–1758. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Clinical Trial Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. Critical Care Medicine. Aug 2008;36(8):2238–43. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wunsch H, Angus DC, Harrison DA, et al. Variation in critical care services across North America and Western Europe. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(10):2787–e8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186aec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Critical Care Medicine. February 2012;40(2):502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Critical care medicine. 2011;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan C, Timmins F, Thompson DR. Post-intensive care syndrome: A concept analysis. International Journal Of Nursing Studies. 2021;114:103814–103814. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Critical Care Medicine. Feb 2012;40(2):618–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. Oct 3 2013;369(14):1306–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu NN, Zhang YB, Wang SY, Zhao YH, Zhong XM. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors of delirium in ICU patients: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nursing In Critical Care. 2023;28(5):653–669. 10.1111/nicc.12857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Kang J, Jeong YJ. Risk factors for post–intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian Critical Care. 2020;33(3):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasilevskis EE, Ely EW, Speroff T, Pun BT, Boehm L, Dittus RS. Reducing iatrogenic risks: ICU-acquired delirium and weakness--crossing the quality chasm. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.Review. Chest. Nov 2010;138(5):1224–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topp R, Ditmyer M, King K, Doherty K, Hornyak III J. The effect of bed rest and potential of prehabilitation on patients in the intensive care unit. AACN advanced critical care. 2002;13(2):263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul N, Buse ER, Knauthe A-C, Nothacker M, Weiss B, Spies CD. Effect of ICU care bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes: a scoping review. BMJ open. 2023;13(2):e070962. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geense WW, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, Vermeulen H, Hannink G, Zegers M. Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(11):1607–1618. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sosnowski K, Lin F, Chaboyer W, Ranse K, Heffernan A, Mitchell M. The effect of the ABCDE/ABCDEF bundle on delirium, functional outcomes, and quality of life in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal Of Nursing Studies. 2023;138:104410. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marini JJ. Tidal volume, PEEP, and barotrauma: an open and shut case? Chest. 1996;109(2):302–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttormson JL, Chlan L, Weinert C, Savik K. Factors influencing nurse sedation practices with mechanically ventilated patients: a US national survey. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2010;26(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. N Engl J Med. Feb 20 2003;348(8):683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. N Engl J Med. Apr 7 2011;364(14):1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Critical Care Medicine. Jan 2002;30(1):119–41. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calle GHL, Martin MC, Nin N. Buscando humanizar los cuidados intensivos. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva. 2017;29:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu K, Nakamura K, Katsukawa H, et al. Implementation of the ABCDEF bundle for critically ill ICU patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-national 1-day point prevalence study. Frontiers In Medicine. 2021;8:735860. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.735860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa DK, White M, Ginier E, et al. Identifying barriers to delivering the ABCDE bundle to minimize adverse outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients: A systematic review. Chest. Apr 21 2017; doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balas MC, Pun BT, Pasero C, et al. Common challenges to effective ABCDEF bundle implementation: The ICU liberation campaign experience. Critical Care Nurse. 2019;39(1):46–60. doi: 10.4037/ccn2019927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehm LM, Dietrich MS, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Perceptions of workload burden and adherence to ABCDE bundle among intensive care providers. American Journal Of Critical Care: an official publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Jul 2017;26(4):e38–e47. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2017544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eikermann M, Needham DM, Devlin JW. Multimodal, patient-centred symptom control: a strategy to replace sedation in the ICU. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2023;11(6):506–509. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guttormson JL, Khan B, Brodsky MB, et al. Symptom assessment for mechanically ventilated patients: principles and priorities: an official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2023;20(4):491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical care medicine. Sep 2018;46(9):e825–e873. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes-Daly MA, Phillips G, Ely EW. Improving Hospital Survival and Reducing Brain Dysfunction at Seven California Community Hospitals: Implementing PAD Guidelines Via the ABCDEF Bundle in 6,064 Patients. Critical care medicine. Feb 2017;45(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel BK, Wolfe KS, Patel SB, et al. Effect of early mobilisation on long-term cognitive impairment in critical illness in the USA: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2023;11(6):563–572. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00489-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menges D, Seiler B, Tomonaga Y, Schwenkglenks M, Puhan MA, Yebyo HG. Systematic early versus late mobilization or standard early mobilization in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care. 2021;25:1–24. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang YT, Lang JK, Haines KJ, Skinner EH, Haines TP. Physical rehabilitation in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2022;50(3):375–388. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu LR, Jia WJ, Tian WM, Cha HT, Yong JJ. Optimal timing for early mobilization initiatives in intensive care unit patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2023:103607. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jenkins AS, Isha S, Hanson AJ, et al. Rehabilitation in the intensive care unit: How amount of physical and occupational therapy affects patients’ function and hospital length of stay. PM&R. 2024;16(3):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strom T, Martinussen T, Toft P. A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomised trial. Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t. Lancet. Feb 6 2010;375(9713):475–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen HT, Nedergaard HK, Strøm T, et al. Nonsedation or light sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(12):1103–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nedergaard HK, Jensen HI, Stylsvig M, Olsen HT, Strøm T, Toft P. Effect of non‐sedation on post‐traumatic stress and psychological health in survivors of critical illness—A substudy of the NONSEDA randomized trial. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2020;64(8):1136–1143. doi: 10.1111/aas.13648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaeza NN, Delgado MCM, La Calle GH. Humanizing intensive care: toward a human-centered care ICU model. Critical Care Medicine. 2020;48(3):385–390. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basile MJ, Rubin E, Wilson ME, et al. Humanizing the ICU patient: a qualitative exploration of behaviors experienced by patients, caregivers, and ICU staff. Critical Care Explorations. 2021;3(6):e0463. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuruppu NR, Chaboyer W, Abayadeera A, Ranse K. Augmentative and alternative communication tools for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care units: A scoping review. Australian Critical Care. 2023;36(6):1095–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2022.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.González-Caro D, Blázquez-Romero V, Garnacho-Montero J. “Balcony of Hope”: a key element of new intensive care units. Intensive Care Medicine. 2023;49(3):379–380. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasano N, Kato Y, Tanaka A, Kusama N. Out-of-the-ICU mobilization in critically ill patients: the safety of a new model of rehabilitation. Critical Care Explorations. 2022;4(1):e0604. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merriam-Webster Inc. The Merriam-Webster dictionary. Merriam-Webster; 2005:xviii, 701 p. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabb N, Fernbach PM, Sloman SA. Individual representation in a community of knowledge. Trends In Cognitive Sciences. 2019;23(10):891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barr J, Ghaferi AA, Costa DK, et al. Organizational characteristics associated with ICU liberation (ABCDEF) bundle implementation by adult ICUs in Michigan. Critical Care Explorations. 2020;2(8):e0169. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wongtangman K, Santer P, Wachtendorf LJ, et al. Association of sedation, coma, and in-hospital mortality in mechanically ventilated patients with coronavirus disease 2019–related acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49(9):1524–1534. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuchita M, Blaine C, Keyworth A, et al. Perspectives on sedation among interdisciplinary team members in ICU: A survey study. Critical Care Explorations. 2023;5(9):e0972. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guttormson JL, Chlan L, Tracy MF, Hetland B, Mandrekar J. Nurses’ attitudes and practices related to sedation: A national survey. American Journal of Critical Care. 2019;28(4):255–263. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2019526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nydahl P International survey of intensive care clinicians: Would you like to be sedated in case of a critical care admission? Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2024;80:103577. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ely EW. The ABCDEF Bundle: Science and Philosophy of How ICU Liberation Serves Patients and Families. Critical Care Medicine. Feb 2017;45(2):321–330. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller MA, Bosk EA, Iwashyna TJ, Krein SL. Implementation challenges in the intensive care unit: the why, who, and how of daily interruption of sedation. Journal of Critical Care. 2012;27(2):218. e1–218. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sneyers B, Laterre P-F, Perreault MM, Wouters D, Spinewine A. Current practices and barriers impairing physicians’ and nurses’ adherence to analgo-sedation recommendations in the intensive care unit-a national survey. Critical Care. 2014;18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brockman A, Krupp A, Bach C, et al. Clinicians’ perceptions on implementation strategies used to facilitate ABCDEF bundle adoption: A multicenter survey. Heart & Lung. 2023;62:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donovan AL, Aldrich JM, Gross AK, et al. Interprofessional care and teamwork in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2018;46(6):980–990. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hickmann CE, Castanares-Zapatero D, Bialais E, et al. Teamwork enables high level of early mobilization in critically ill patients. Annals of Intensive Care. 2016;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chohan S, Ash S, Senior L. A team approach to the introduction of safe early mobilisation in an adult critical care unit. BMJ Open Quality. 2018;7(4):e000339. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, Lamprell G, Testa L. Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review protocol. BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e013758. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plsek P, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ [Internet]. 2001. [cited 2017 Feb 20]; 323 (7313): 625–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Nugus P, Plumb J. Health care as a complex adaptive system. 2013. Resilient health care [Internet] Farnham, Surrey, UK England: AshgateAshgate Studies In Resilience Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science. 2009;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Linnan LA. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Education Research. 2009;24(2):292–305. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hager DN, Dinglas VD, Subhas S, et al. Reducing deep sedation and delirium in acute lung injury patients: a quality improvement project. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41(6):1435–1442. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Archives Of Physical Medicine And Rehabilitation. 2010;91(4):536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Engel HJ, Needham DM, Morris PE, Gropper MA. ICU early mobilization: from recommendation to implementation at three medical centers. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41(9):S69–S80. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a240d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Needham DM, Korupolu R. Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: implementation of a quality improvement model. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. Jul-Aug 2010;17(4):271–81. doi: 10.1310/tsr1704-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azar J, Glantz E, Solid C, Holden R, Boustani M. Using Agile Science for Rapid Innovation and Implementation of a New Care Model. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 2023;40(2):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hashemi S, Bai L, Gao S, Burstein F, Renzenbrink K. Sharpening clinical decision support alert and reminder designs with MINDSPACE: A systematic review. International journal of medical informatics. 2023:105276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]