Abstract

Introduction:

Adolescent depression is prevalent, and teen suicide rates are on the rise locally. A systemic review to understand associated risk and protective factors is important to strengthen measures for the prevention and early detection of adolescent depression and suicide in Singapore. This systematic review aims to identify the factors associated with adolescent depression in Singapore.

Methods:

A systematic search on the following databases was performed on 21 May 2020: PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Full texts were reviewed for eligibility, and the included studies were appraised for quality using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. Narrative synthesis of the finalised articles was performed through thematic analysis.

Results:

In total, eight studies were included in this review. The four factors associated with adolescent depression identified were: (1) sociodemographic factors (gender, ethnicity); (2) psychological factors, including childhood maltreatment exposure and psychological constructs (hope, optimism); (3) coexisting chronic medical conditions (asthma); and (4) lifestyle factors (sleep inadequacy, excessive internet use and pathological gaming).

Conclusion:

The identified factors were largely similar to those reported in the global literature, except for sleep inadequacy along with conspicuously absent factors such as academic stress and strict parenting, which should prompt further research in these areas. Further research should focus on current and prospective interventions to improve mental health literacy, targeting sleep duration, internet use and gaming, and mitigating the risk of depression in patients with chronic disease in the primary care and community setting.

Keywords: Adolescent health, depression, mental health, risk factors, Singapore

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence (10–19 years, World Health Organization [WHO])[1] is a period of rapid physical, cognitive and social transformation that leads to acquisition of the roles and responsibilities of adulthood. While adolescents are mostly physically healthy, this period is marked by experimentation and risk taking,[2] and significant morbidity in terms of mental illness. Half of all mental health problems have an onset before the age of 14, and three-quarters before the age of 25.[3]

Depression is a leading cause of illness and disability globally. With an estimated 1-year prevalence of 4%–5% of depression among youth in the mid- to late-adolescent age group,[4,5] it poses a threat to adolescent well-being. Adolescent depression is associated with health-compromising behaviours, such as smoking and substance abuse, and a higher prevalence of and poorer outcomes for chronic medical conditions such as obesity[6] and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.[7] It also heightens the risk of suicide,[8] the third leading cause of death among 15–19-year-olds worldwide,[9] and is an impediment to socio-educational attainment.[10,11] The United Nations Youth Strategy (UN2030) has prioritised the provision of youth-friendly mental health services to address the adverse trajectories of patients and their families that may result from untreated adolescent depression.[10,11]

Locally, the Singapore Mental Health Survey (SMHS 2016)[12] found that the lifetime prevalence of depression in adults aged 18 years and above increased from 5.8% in 2010 to 6.3% in 2016. Mental disorders contribute to 20%–25% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), 20%–25% of years of life lost (YLL) and 25%–30% of years lived with disability (YLD). In Singapore, anxiety and depressive disorders are the leading cause of disease burden among 15–34-year-olds and rank fifth in the 0–14 years age category. In 2019, almost 2,000 youth (aged 16–30 years) engaged CHAT (Community Health Assessment Team), a community-based youth mental health outreach, an increase of 36 times from its inception in 2009.[13,14] In Singapore, suicide remains the leading cause of death for persons aged 10–29 years. Among adolescents aged 10–19 years, a high of 19 suicides among teen males were documented in 2018. Among females, ten teen suicides were documented in 2019, a more than three-fold increase from 2018.[15] Hence, at the 2019 Youth Conversations organised by the National Youth Council, mental health was cited as an issue of national concern among youth.

There are many factors associated with depression. These include a strong family history of depression,[16,17,18] sleep deprivation, genetic factors[19] and the presence of chronic medical conditions. Predisposing factors include history of mental disorders, attempted self-harm, disruptive behaviour, learning problems, negative body image, heightened sensitivity to loss and rejection, chronic adversity including maltreatment, family discord, bullying and poverty,[20] as well as frequent clinic attendance, lack of social support and lower socioeconomic status. Stressors such as academic pressure, abuse, personal injury and loss[20,21,22] act as additional risk factors.

Singapore is a Southeast Asian city-state at the crossroads of global trade, imbued with a sociocultural amalgamation of Asian collectivism[23,24,25] and Western individualism,[26] and oriented nationally towards academic and economic competitiveness.[27] This systematic review seeks to understand the risk and protective factors associated with depression among adolescents growing up in multicultural Singapore.

METHODS

Design and search strategy

The protocol for this review was designed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. We conducted a systematic search on the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO on 21 May 2020 with adapted search terms for each database [see Appendix]. The following search terms were used: ‘depressi* OR MDD OR dysthymia OR dysthymic disorder’ AND ‘adolescent* OR adolescence OR teen* OR youth*’ AND ‘singapore’ AND ‘factor OR associat* OR relationship* OR Predict OR Prevalence OR Course OR prognos* OR cause OR etiolog* OR aetiolog*’. In order to ensure sufficient data, the search strategy did not limit studies by study design.

Selection criteria

All reports that examined the risk factors for depression in the adolescent population were eligible for inclusion. We took adolescence to refer to individuals aged between 10 and 19 years according to the WHO definition.[1] We considered articles for review if they satisfied the following inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed scientific reports of original research; English language articles; study population with a mean age of 10–19 years; study population resided in Singapore; and studies that reported associations with depression as an outcome measure. The exclusion criteria were informal publications (such as commentaries, letters to the editor, editorials, meeting abstracts), review papers, non-English papers, studies with lack of access to full texts and studies that did not focus on depression as an outcome. The selection of documents for eligibility was evaluated independently, first using the title and abstract and subsequently using the full text, to ensure they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Quality appraisal

All included studies were appraised using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. The scores for risk of bias are tabulated in Table 1. The quality appraisal process was peer reviewed by the team of authors. The studies were ranked to be of good, fair or poor quality based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards [Table 2].

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment.

| Study | Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Selection (max. 5) | Comparability (max. 2) | Outcome (max. 3) | |

| Magiati et al. (2015)[30] | 5 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Mythily et al. (2008)[37] | 2 | 0 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Peh et al. (2017)[32] | 2 | 1 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Wong and Lim (2009)[33] | 4 | 2 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Yeo et al. (2019)[35] | 5 | 2 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Lu et al. (2014)[34] | 2 | 2 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Lo et al. (2018)[36] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

| |||

| Gentile et al. (2011)[38] | 3 | 2 | 2 |

Table 2.

Quality assessment interpretation (AHRQ standards).

| Quality assessment | Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Selection (max. 5) | Comparability (max. 2) | Outcome (max. 3) | |

| Good quality | 3 or 4 | 1 or 2 | 2 or 3 |

|

| |||

| Fair quality | 2 | 1 or 2 | 2 or 3 |

|

| |||

| Poor quality | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 |

AHRQ: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Data synthesis

The included papers were qualitatively and thematically analysed to produce a narrative synthesis.[28] A preliminary synthesis was first undertaken by one member of the research team, and the identified categories were subsequently cross-checked and discussed with another member. The researchers met to discuss any disagreements that arose, and any differences in opinion were resolved through consensus. No ethics approval was required for this review.

RESULTS

Search results

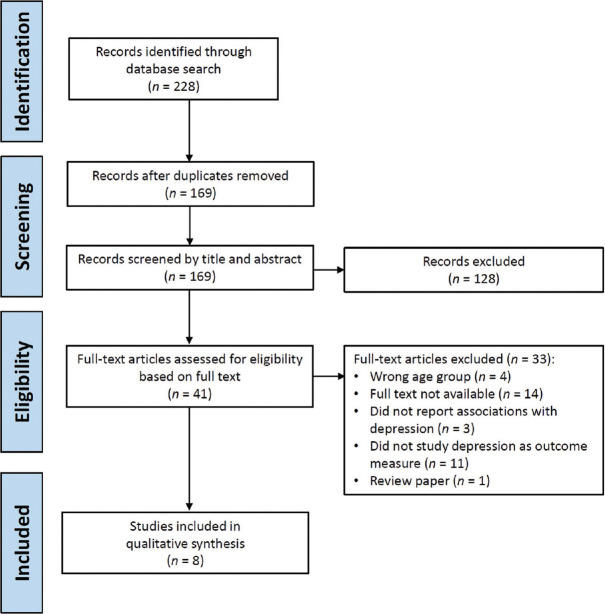

The literature search yielded 94, 116 and 18 search results from PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO, respectively, totalling 228 studies. After 59 duplicates were removed, 169 titles and abstracts were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which 128 articles were excluded. Of the remaining 41 full-text articles, 33 additional studies were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, leaving eight articles finally. With no restrictions on study design, we have included seven cross-sectional studies and one interventional study. Given the diversity of risk factors, variability in study designs and lack of common data, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

All eight studies were conducted in Singapore, with sample sizes ranging from 108 to 2998 and study settings ranging from hospital (n = 2) to school (n = 6) settings. Regarding the depression measures used, one study did not use a validated depression scale, two studies used similar depression scales and one study used a depression scale validated in Singapore (Asian Adolescent Depression Scale).[29] A summary of the search results is presented in the PRISMA flowchart [Figure 1]. The study characteristics and summary of the results are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart shows the selection process for the current systematic review. [Adapted from: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement BMJ 2009; 339.]

Table 3.

Summary of study characteristics and results.

| Study | Themes according to theoretical framework: social, biological, psychological | Study design | Setting | Sample source and source of data | Sample size | Depression measure used | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magiati et al. (2015)[30] | Social: ethnicity Biological: gender | Cross-sectional | School | Self-reported questionnaire in 18 primary schools | 1,655 | CDI | Chinese had a lower CDI total, negative mood, anhedonia and ineffectiveness than Malays. Males scored higher for ‘interpersonal problems’ than females. Compared to the US population from another study, Singapore children had higher CDI, with females scoring higher in several CDI domains |

|

| |||||||

| Mythily et al. (2008)[37] | Psychological: excessive internet use | Cross-sectional | School | Self-reported questionnaire in three secondary schools | 2,735 | Not reported | Participants who reported excessive internet use, defined by the author as >5 h a day, were more likely to feel sad or depressed |

|

| |||||||

| Peh et al. (2017)[32] | Psychological: traumatic childhood | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Self-reported questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic | 108 | PHQ-8 | Severity of maltreatment exposure (measured to include physical, sexual and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect) was associated with depressive symptoms |

|

| |||||||

| Wong and Lim (2009)[33] | Psychological: hope and optimism | Cross-sectional | School | Self-reported questionnaire in a secondary school | 340 | CES-D | Optimism scores and depression scores were negatively correlated. Hope scores and depression scores were negatively correlated. Hope and optimism contributed significantly to depression even after controlling for optimism and hope, respectively. Hope did not account for depression beyond what was accounted for by optimism. Optimism, pessimism and agency were significantly predictive of depression |

|

| |||||||

| Yeo et al. (2019)[35] | Biological: sleep deprivation | Cross-sectional | School | Self-reported questionnaire in six local and international secondary schools | 2,313 | 11-item Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale | Shorter sleep was associated with a higher global depression score. Having <7 h of sleep compared to an age-appropriate (8−10 h) amount of sleep was associated with depressive symptoms |

|

| |||||||

| Lu et al. (2014)[34] | Biological: asthma | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Self-reported questionnaire in one hospital | 171 | Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale | Adolescents with poorly controlled asthma reported significantly more depressive symptoms than subjects with well-controlled asthma and healthy controls. Number of subjects who were disturbed by depressive symptoms was found to be higher among participants with asthma, especially those with poorly controlled asthma. Increased ACT score was associated with lower depression scores |

|

| |||||||

| Lo et al. (2018)[36] | Biological: sleep deprivation | Cohort study | School | Self-reported questionnaire in all-girls secondary school | 375 | 11-item Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale | Increase in TIB on weekdays was associated with decrease in depressive symptoms |

|

| |||||||

| Gentile et al. (2011)[38] | Psychological and social: pathological video gaming | Cohort study | School | Self-reported questionnaire in six primary schools and six secondary schools | 2,998 | Asian Adolescent Depression Scale | Children with more pathological gaming symptoms at baseline had higher levels of depression at 2-year follow-up. Increase in pathological gaming symptoms between baseline and follow-up was associated with further increase in depression at follow-up. Those who became pathological gamers ended up with increased depression, and those who stopped being pathological gamers had lower depression than those who remained pathological gamers |

ACT: Asthma Control Test, CDI: Children’s Depression Inventory, CES-D: Centre of Epidemiological Studies-Depressed Mood Scale, PHQ-8: 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire, TIB: time in bed

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment scores ranged from 4 to 9 [Table 1]. Half the studies did not have a representative sample (selection score of 2 and below) mostly because they had a target group of a selected group of users rather than a random or non-random sample. Some papers also fared lower in the representativeness of the sample because they did not include the response rate of responders/non-responders or did not justify their sample size. Nonetheless, most of the studies controlled for factors and had good quality of outcomes reported.

Factors identified

The factors identified were categorised into: (1) sociodemographic factors (gender, ethnicity); (2) psychological factors, including childhood maltreatment exposure and psychological constructs (hope, optimism); (3) coexisting chronic medical conditions (asthma); and (4) lifestyle factors (sleep inadequacy, excessive Internet use, pathological gaming).

Sociodemographic factors

Magiati et al.[30] found that a substantial minority (16.9%) of primary school-aged Singapore children (age 8–12 years) reported depressive symptoms based on the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), which was higher than that reported by Ramli et al.[31] for Malaysian secondary school-aged adolescents (10.3%).

Although little clinically significant difference in CDI scores was found between Malay, Indian and Chinese children, Chinese children were observed to report lower scores for depressive symptoms (negative mood, interpersonal problems and anhedonia, and total CDI score) compared to their Malay and Indian peers.

While some gender differentiation was noted between Indian girls who reported more emotional symptoms than Indian boys, the study found no clinically significant difference in total depression scores between males and females.

Psychological factors

Peh et al.[32] who recruited adolescents (age 14–19 years) from a psychiatric hospital reported increased depressive symptoms among patients with more severe childhood maltreatment exposure. The psychometric instruments in this study collected data on physical, sexual and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect, self-harm behaviours, emotional dysregulation and depressive symptoms. In this study, 75.9% reported at least one episode of self-harm, while 50.5% reported ten or more episodes in the past 12 months. The study found that emotional dysregulation mediated the association between severity of maltreatment exposure and self-harm frequency.

Wong and Lim[33] explored the discriminant validity of ‘hope’ and ‘optimism’ on depression and life satisfaction among Singapore secondary school students. Both constructs were oriented towards positive outcome expectancies, correlating positively with life satisfaction and negatively with depression. While ‘optimism’ was related more to general positive outcomes, ‘hope’ had the element of personal self-efficacy in goal attainment. ‘Hope’ includes the sub-elements of agency thinking (the motivation to pursue one’s goals) and pathway thinking (the planning of a pathway towards goals attainment). Further correlational analysis found that agency thinking correlated negatively with depression, while pathway thinking did not. Interestingly, the study noted gender differences in that males tended to score higher in the ‘hope’ domain, which was protective for depression symptoms.

Chronic medical conditions

In a cross-sectional study, Lu et al.[34] recruited adolescent patients (age 12–19 years) with asthma from a hospital and then compared the rates of depression with age- and gender- matched non-asthma control individuals from the same neighbourhood. They found that adolescents with poorly controlled asthma had higher scores of depression compared to healthy controls and patients whose asthma was well controlled.

Lifestyle factors

Two studies reported the effect of sleep deprivation on depressive symptoms. Not achieving age-appropriate sleep duration (8–10 h) on school nights was associated with significantly increased odds for depressive symptoms (sadness, irritability, worthlessness, low motivation, thoughts of self-harm) as well as poorer self-rated health and increased odds of being overweight.[35,36] In an interventional study investigating the effects of delaying school start time by 45 min, a sustained increase of time in bed (TIB) and total sleep time (TST) was documented at 9 months. This was associated with improved alertness, reduction in depressive symptoms and improvement in depression scores (from baseline to 9 months change: −1.22 ± 0.48, P < 0.01).[35,36]

Two studies reported associations between excessive use of the internet and related media and depressive symptoms in adolescents. One cross-sectional study reported that 17.1% of adolescents used the internet excessively (defined as more than 5 h of internet use a day), and this was significantly associated with lack of home rules regarding internet use, a lower likelihood of having a confidant, feelings of sadness and depression and perceived poorer grades in school.[37] Gentile et al.[38] conducted a prospective cohort study in a population of secondary school children over 2 years to research the association of pathological gaming with depression in adolescents. The study found the prevalence of pathological gaming to be around 9%. Predictor variables of pathological gaming included impulsiveness, lower social competence and poorer emotional regulation skills. In turn, severity of pathological gaming was associated with depression, anxiety, social phobia and poorer grades. These improved when the individual stopped being a pathological gamer.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesised the scientific literature for factors associated with depression among adolescents in Singapore. Despite a modest yield of eight papers, the findings from this review are reflective of the range of factors associated with adolescent depression locally. The summaries of recommendations are provided in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Summary of recommendations based on intervention.

| Factor | Detection | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health literacy | Improved mental literacy in the community (parents, teachers, adolescents) will reduce stigma and allow for early detection of mental illness | Strengthen mental health literacy in the community, including parents, teachers, guardians, students, adolescents. A community-wide effort to strengthen mental health literacy may reduce mental health stigma and aid in the early detection and treatment of depression in the community |

| Train adolescents in emotional resilience/regulation. Programmes within schools include the SEL[118] items in schools. A wide range of programmes available to the public include the tMHFA and YMHFA,[125] mindfulness-based programmes and youth-empowerment programmes | ||

| Skills in emotional regulation, coping with adversity and identifying maltreatment,[133,134] and identification and modification of maladaptive cognitions/beliefs and behaviours can be taught to adolescents[135,136,137,138,139] | ||

|

| ||

| Primary care practitioner | Primary care physicians should be trained to develop a health index of suspicion and detect depression risk among patients in the community | Healthcare providers should be equipped for early detection and treatment of adolescent patients with mental health problems. This may include asking specific questions in the history, using the HEADSSS framework for health risk behaviour and mental health screening and using screening tools in the waiting area |

| Further mental health training opportunities include the GDMH and counselling skills | ||

|

| ||

| Sleep | Screening for sleep deprivation or poor sleep hygiene in adolescents | Adolescents should be asked about their sleep |

| Recommend a sleep duration of at least 6 h per night | ||

| Sleep enhancement: Sleep duration can be improved with adjustment of school start time, reduction of school workload,[122] setting appropriate bedtime[123] and reinforcing sleep hygiene and parental training | ||

|

| ||

| Internet use/gaming | Screening for excessive internet use and gaming addiction | Limiting internet exposure: Parental limitation of internet usage and gaming and rescheduling sleep-disrupting media use at night.[140] Family therapy[141] forms as a great support system to prevent internet addiction in the future |

| Adolescents should be asked about internet use and use of social media. The HEADSSSS tool (with additional S for social media) for screening can be used[87,88,89] | ||

|

| ||

| Chronic disease | Screening for concomitant depression in adolescents with underlying chronic disease | Controlling chronic comorbidity: Adequate medical treatment for underlying medical comorbidity can reduce discomfort and the risk of depression |

| Explore the mental health of patients with poorly controlled chronic disease | ||

| Known factors (not limited to) insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,[61,62] inflammatory bowel disease[63,64] and asthma[34] | ||

GDMH: graduate diploma in mental health, SEL: socio-emotional learning, tMHFA: teen Mental Health First Aid, YMHA: Youth Mental Health First Aid

Table 5.

Summary of recommendations based on factors.

| Factor identified | Subfactor | Reference | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | Gender and ethnicity | Magiati et al. (2015)[30] | Identifying those at risk for earlier detection of mental health issues |

| Better mental health literacy: Greater advocacy for mental health awareness will aid in early detection of depression and allow prompt treatment | |||

| Examples (not limited to): Teen and Youth Mental Health First Aid,[125] Silver Ribbon,[127] SAMH[126] | |||

|

| |||

| Psychological | Childhood maltreatment exposure | Peh et al. (2017)[32] | Screening for emotional dysregulation or maltreatment history in adolescents to determine possible underlying depression risk |

|

|

|||

| Psychological constructs (hope, optimism) | Wong and Lim (2009)[33] | Emotional resilience training: Skills in emotional regulation and coping with adversity | |

| Examples (not limited to): REACH,[120,121] cultivating resilience,[129,130,131,132] identifying maltreatment,[133,134] modification of cognition/beliefs and behaviour[135,136,137,138,139] | |||

|

| |||

| Chronic medical condition | Chronic medical conditions | Lu et al. (2014)[34] | Screening for concomitant depression in adolescents with underlying chronic disease |

| Controlling chronic comorbidities: Adequate medical treatment for underlying medical comorbidities can reduce discomfort and the risk of depression | |||

| Known factors (not limited to) insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,[61,62] inflammatory bowel disease[63,64] and asthma[34] | |||

|

|

|||

| Lifestyle | Sleep duration | Yeo et al. (2019)[35] | Screening for sleep deprivation or poor sleep hygiene in adolescents |

| Lo et al. (2018)[36] | Sleep enhancement: Sleep duration can be improved with adjustment of school start time, reduction of school workload,[122] setting appropriate bedtime,[123] reinforcing sleep hygiene and parental training | ||

| Recommended sleep duration: 6 h per night | |||

|

|

|||

| Excessive internet use and related media | Gentile et al. (2011)[38] | Screening for excessive internet use and gaming addiction | |

| Mythily et al. (2008)[37] | Limiting internet exposure: Parental limitation of internet usage and gaming and rescheduling sleep-disrupting media use at night.[140] Family therapy[141] forms as a great support system to prevent internet addiction in the future | ||

| HEADSSSS tool (with additional S for social media) for screening can be used[87,88,89] | |||

REACH: Response, Early interventions and Assessment in Community mental Health, SAMH: Singapore Association for Mental Health

Sociocultural factors

Sociocultural factors play a significant role in terms of mental wellness.[39,40] A study of local adults has shown that Indians have significantly higher rate of depression compared to Chinese and Malays.[41] While Magiati et al.’s[30] paper did not show any significant differences between Chinese, Indian and Malay primary school children in terms of self-reported depression, the tendency towards lower scores for depressive symptoms among Chinese students compared to their Malay and Indian counterparts may be related to the adversity experienced by the ethnic minority groups[42] and possibly an under-reporting of symptoms of Chinese children in order to avoid ‘loss of face’.[43]

In terms of gender, adolescent females have been observed to be at a higher risk of depressive symptoms,[44,45,46] attributable in part to the pubertal changes in the hormone–brain relationship[47,48] and to the emergence of received sociocultural gender roles that may include the need to internalise symptoms[49] among girls more than among boys.[50,51,52] In this review, primary school-aged Indian girls were found to have higher scores for emotional symptoms than Indian boys, which may be reflective of the increasing influence of traditional gender roles during adolescence.[53] Nonetheless, the full effects of sociocultural differentiation on well-being may not be well reflected in Magiati et al.’s[30] paper as the school-aged participants would have just been at the cusp of assuming their sociocultural and gender roles.

Adverse childhood events

The lifetime prevalence of adverse childhood events (ACE) of Singapore residents aged 18 years and above is 63.9%.[54] ACE and childhood maltreatment are associated with increased risk of adolescent depression and mental disorders across the lifespan.[55,56,57] Postulated mechanisms include the scars of increased self-criticism, negative cognitive styles and the fear of rejection later in life.[32] Peh et al.[32] identified emotional dysregulation as a mediator between childhood maltreatment exposure and the risk of self-harm. Wong and Lim,[33] on the other hand, explored the hope and optimism constructs and their negative correlation with depression.[58,59] This concurs with other studies which showed how lack of goal-directed energy (agency thinking) was more predictive of depression than lack of pathway thinking.[60]

Chronic medical conditions

Our review found that poorly controlled asthma was associated with a greater risk of depressive symptoms. This is consistent with other studies which have found that at least one in four adolescents with asthma have symptoms of depression, possibly attributed, at least in part, to restrictions in daily functioning.[34] Chronic conditions linked to adolescent depression in the literature include insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus[61,62] and inflammatory bowel disease.[63,64] These point to the importance of exploring the mental wellness of the adolescent patient who presents at the clinic with poorly controlled asthma.

Sleep

Sleep is crucial for mental wellness, and the cumulative effects of chronic partial sleep deprivation may adversely affect mood and emotional regulation in adolescents.[65,66,67] A nightly sleep duration of 6 h or less increased the risk of depressive symptoms and subsequent major depression.[68] Sleep inadequacy and depression have a bidirectional relationship: insomnia is both a symptom of depression[69] and a factor that adversely affects the success of depression treatment.[70] Sleep inadequacy may be perpetuated by the local school schedules[71] that start 1 h earlier than the stated recommended start time, according to the American Academy of Paediatrics,[72] American Medical Association[73] and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.[74] This may be reflective of the East Asian inclination to prioritise academic achievement over sleep, with students often staying up late to finish uncompleted school assignments.[75]

Excessive internet use

Touted as a smart city[76] with near-total computer and internet penetration (89% and 98% of households, respectively),[77] Singapore has an adolescent population that widely uses the internet and is adept at online gaming. However, excessive use of the internet and pathological gaming are associated with depressive symptoms. Both may spur a downward spiral that compounds social isolation[78] and reinforces depression.

In a milieu that often values public self-restraint[79,80] above public self-expression,[43,81,82,83,84,85] the internet world provides a ready means of escape from the restrictions of the real world.[43] As a mediating factor between internet dependence and depression, the tendency to internalise feelings may play a significant role in the onset of depression and may be predictive of poorer mental health and well-being in middle adulthood.[86] So entwined is the cyber world with the contemporary adolescent experience that ‘social media use’ has been added[87] to the HEADSSS tool[88,89] to encourage practitioners to inquire about cyber wellness when assessing the psychosocial risk of adolescents.

Conspicuously absent: academic stress and parental expectations

Academic achievement is a prime preoccupation in Singapore households. The consistent high national ranking in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA),[90,91] regular stellar performances in the International Baccalaureate (IB) diploma programme[92] and a thriving private supplementary tutoring mill, which starts from the preschool years for some,[93] attest to this national hyperfocus.[94] Though schoolwork was ranked by youths as the most stressful aspect of their lives in a national survey,[95] it was surprising that academic stress was not explicitly studied as a factor in the papers reviewed.

Closely linked to academic stress and equally conspicuous because of its absence is the matter of parental expectations. Different from Western households that may value social development[96] no less than academic achievement, schooling may often be a major focus of family time, effort and source of contention in East Asian households.[97,98,99] Risk factors that relate to parenting styles and depression include parental overprotection,[100,101,102] psychological control[103] and the teenage fear of being the source of parental disappointment.[104] Compared to their European–American counterparts, Asian parents tend to adopt an authoritarian parenting style[105,106] that demands from children the commitment to hard work, self-discipline and obedience,[107] often measured by academic performance. The adolescent tussle for autonomy in such circumstances is a ground for distress and depression,[108] and practitioners do well to provide guidance to parents on the effects of parenting on adolescents’ well-being. The high reported rate of depression (CDI, 16.9%) in Magiati et al.’s[30] paper, articles on sleep deprivation on school nights[109,110] and their effects on school performance and depression,[66,67,111,112,113] as well as studies on excessive computer use[37,38] and their adverse effects on school performance allude to the influential role that parenting styles and academic stress play in adolescent mental health in Singapore.

Comparison with our counterparts

Singapore is a multiethnic, multilingual society with coexisting traditionally Asian and modern Westernised values, with risk factors for depression largely similar to those reported in the global literature.[114,115,116] Despite Western influence, local mental health literacy falls short of that other developed countries, with a pervasive tendency to label depression as a ‘weakness’ caused by lack of resilience,[39] rather than as a medical condition. With influence from traditional Asian values, Singaporean children tend to have higher rates of internalising problems compared to externalising problems,[43] which is the opposite of that seen in Western children, further deterring early detection of adolescent depression.

Practical implications

This review underlies the need for an all-of-society effort to address adolescent mental health. In addition to policy-level initiatives, this would include enlisting schools, social service organisations (SSOs), psychological services, ground-up community efforts,[117] as well as the primary and hospital specialist healthcare services as part of an overarching evidence-informed strategy to address youth mental wellness.

Sleep habits

Sleep deprivation is both a harbinger and symptom of distress and depression. Primary care physicians should enquire about the sleep patterns and sleep hygiene of an adolescent patient during consultation, and encourage a healthy sleep routine.

Internet use

Adolescents and their parents who present at the clinic should likewise be asked about the adolescent patient’s use of the internet. Excessive internet use may prompt the need to screen for distress, schoolwork and relationships, as well as depression and other mental health problems. The accessibility of primary care in the community makes it an excellent venue to enquire about internet use and the adolescents’ experience of stress and coping and to provide opportunistic advice on healthy gaming and internet use, particularly for sleep-deprived gamers.

Chronic disease

In our review, poor asthma control was found to be a risk for adolescent depression. Given the bidirectional relationship of chronic disease control and depression, the patient with poor chronic disease control should as much be screened for depressive symptoms[34,61,62,63,64] as a patient with depressive symptoms is asked about the control of his/her chronic disease condition.

Mental health literacy

The strengthening of mental health literacy across all levels of society — policymaking, school, parental/family and personal/adolescent levels — facilitates the possibility of a collective strengthening of emotional awareness and self-regulation in the community and earlier help-seeking for mental health matters among adolescents.

Educational efforts to address adolescent mental wellness in our schools include socio-emotional learning (SEL)[118] in the Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) curricula widely embedded in primary and secondary schools.[119] The system of Response, Early interventions and Assessment in Community mental Health (REACH)[120,121] team working with school counsellors addresses the mental health issues that may arise in the school setting.[117,120,121] In addition, improving sleep through bold interventions, such as the adjustment of school start times, a reduction of schoolwork,[122] a deliberate setting of bedtimes,[123] reinforcement of good sleep hygiene and parental education, plays an important role in adolescent mental wellness.

At the community level, SSOs and ground-up initiatives provide a diverse range of community-based youth services and empowerment programmes for youth (e.g. Impart,[124] mental health first aid (MHFA),[125] Project 180,[124] Singapore Association for Mental Health (SAMH),[126] Silver Ribbon,[127] TOUCH Youth Intervention[128]). They equip adolescents with the skills to cope with adversity, cultivate resilience,[129,130,131,132] identify maltreatment,[133,134] modify maladaptive cognitions[135,136,137,138,139] and address pathological Internet use; also, they provide interventions to reduce sleep disruption[140] and family therapy[141] if and when required. Teen Mental Health First Aid (tMHFA) and Youth Mental Health First Aid (YMHFA) are programmes that have been shown to be effective in improving mental health literacy.[125]

Role of primary care

Noticeably absent in this review was the role of primary care in supporting adolescent mental health. Perhaps the body of work of primary care physicians in managing adolescent mental health has been left largely unpublished. As the first port of call for patients in the community, primary care physicians in the polyclinics and the approximately 2,000 primary care clinics in private practice should be equipped for the early detection and prompt intervention of adolescent depression when necessary. Local training opportunities for primary care physicians include the Graduate Diploma in Mental Health, and other programmes such as positive psychology, cognitive behavioural therapy and other counselling skills. Primary care physicians also need to be connected to local resources, such as family service centres which may provide counselling and therapy services to clients.

Recommendations for research

This review points to further areas of research in adolescent mental health. Well-designed interventional studies to improve sleep, address excessive internet use, improve the emotional resilience and mental health literacy of adolescents, and studies that venture to modify parenting styles and/or address academic stress may be of value. Research may also branch into factors associated with depression that were not surfaced in this review, such as adolescent temperament,[142] social isolation and loneliness,[143] peer rejection,[144] parental history of depression,[145,146] poor parent–child relationship,[147] poor family attachment and detachment from family activities.[148,149]

On a backdrop of the 2008 WHO/WONCA joint report recommending the greater integration of mental health in primary care,[150] the potential for primary care involvement in adolescent mental health is notable. As mental illness remains largely undetected even in patients seeking medical help, there is value in reducing the missed opportunities for early detection and management of mental illness for adolescents who show up at primary care clinics in the community, especially since onset during adolescence is more frequent.

A health services research agenda to improve the mental health of adolescents in Singapore should start with a mapping of the extent that primary and secondary health care is involved in adolescent mental health detection and management. Interventions such as practitioner training, the strengthening of partnerships between primary and secondary care, and the use of screening questionnaires and technological innovations[151,152] that have shown promise elsewhere to improve mental illness detection at primary care may, subsequently be planned.

CONCLUSION

The results of the eight studies included in this review serve to prompt healthcare practitioners to further explore the mental wellness of adolescent patients in the clinic. In addition, they underline the importance of an all-of-society effort to strengthen mental health literacy in the population to stem the inordinate number of teen suicides seen in recent years. Health services research in adolescent mental health that enlists the extensive reach and care continuity characteristic of primary care in collaboration with paediatricians and psychiatrists shows promise for developing a home-grown evidence base for the improved mental health outcomes of adolescents in Singapore.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content

Appendix at http://links.lww.com/SGMJ/A159

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Ms Monica Ashwini Lazarus, Research Associate, and Dr Miny Samuel, Assistant Director, Dean’s Office (Research) from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore for their support.

APPENDIX

Search strategy and results

A search was conducted on 4th April 2020 on PubMed (94), Embase (116), and PsycINFO (18).

Supplementary Table 1.

PubMed

| No. | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh]) OR (“Depressi*”[title/abstract] OR “MDD”[title/abstract] OR “Dysthymia”[Title/Abstract] OR “Dysthymic disorder”[Title/Abstract]) | 431,555 |

| #2 | (“Adolescent”[Mesh] OR “Child”[Mesh]) OR (“Adolescent*”[title/abstract] OR “adolescence”[title/abstract] OR “teen*”[title/abstract] OR “youth*”[title/abstract]) | 308,2035 |

| #3 | (“Singapore”[Mesh]) OR (“Singapore*”[Title/Abstract]) | 19,344 |

| #4 | “Factor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “associat*”[Title/Abstract] OR “relationship*”[Title/Abstract] OR “predict*”[Title/Abstract] OR “prevalence”[Title/Abstract] OR “course”[Title/Abstract] OR “prognos*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Cause”[Title/Abstract] OR “Etiolog*”[Title/Abstract] OR “Aetiolog*”[Title/Abstract] | 960,0393 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 94 |

Supplementary Table 2.

Embase

| No. | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | ‘depression’/exp OR ‘depressi*’:ti,ab OR ‘mdd’:ti,ab OR ‘dysthymia’:ti,ab OR ‘dysthymic disorder’:ti,ab | 704,475 |

| #2 | ‘adolescent’/exp OR ‘child’/exp OR ‘adolescent*’:ti,ab OR ‘adolescence’:ti,ab OR ‘teen*’:ti,ab OR ‘youth*’:ti,ab | 377,4927 |

| #3 | ‘singapore’/exp OR ‘singapore*’:ti,ab | 29,976 |

| #4 | ‘factor*’:ti,ab OR ‘associat*’:ti,ab OR ‘relationship*’:ti,ab OR ‘predict*’:ti,ab OR ‘prevalence’:ti,ab OR ‘course’:ti,ab OR ‘prognos*’:ti,ab OR ‘cause’:ti,ab OR ‘etiolog*’:ti,ab OR ‘aetiolog*’:ti,ab | 12,460,808 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 116 |

Supplementary Table 3.

PsycINFO

| No. | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (Depressi* OR MDD OR Dysthymia OR Dysthymic disorder).ti,ab. | 284,185 |

| #2 | (Adolescent* OR adolescence OR teen* OR youth*).ti,ab. | 301,282 |

| #3 | Singapore*.ti,ab. | 4,269 |

| #4 | (Factor* OR associat* OR Relationship* OR Predict* OR Prevalence OR Course OR Prognos* OR Cause OR Etiolog* OR Aetiolog*).ti,ab. | 2,123,263 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 | 18 |

Funding Statement

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adolescent Health. [[Last accessed on 2020 Oct 12]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/adolescent-health .

- 2.Sanci L, Webb M, Hocking J. Risk-taking behaviour in adolescents. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018;47:829. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-07-18-4626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:972–86. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchberger B, Huppertz H, Krabbe L, Lux B, Mattivi JT, Siafarikas A. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;70:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet Lond Engl. 2012;379:1056–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adolescent Mental Health. [[Last accessed on 2020 Oct 12]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health .

- 10.Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press; 2008. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents; pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keenan-Miller D, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Health Outcomes related to early adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Shafie S, Chua BY, Sambasivam R, et al. Tracking the mental health of a nation: Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in the second Singapore mental health study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e29. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Big Read: With youths more open about mental health, it's time others learn to listen. CNA. [[Last accessed on 2020 Oct 12]]. Available from: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/mental-health-youths-suicide-depression-listen-11994612 .

- 14.IN FOCUS: The challenges young people face in seeking mental health help. CNA. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/in-focus-young-people-mental-health-singapore-treatment-13002934 .

- 15.The Straits Times Singapore. Youth suicides still a concern, with 94 cases last year and in 2018. Straits Times. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2020 Oct 12]]. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/number-of-suicides-in-2019-did-not-decline-compared-with-2018-youth-suicides-still-a .

- 16.Williamson DE, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Kaufman J, Rao U, et al. A case-control family history study of depression in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1596–607. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199512000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essau CA. The association between family factors and depressive disorders in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2004;33:365–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sander JB, McCarty CA. Youth depression in the family context: Familial risk factors and models of treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005;8:203–19. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-6666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thapar A, Rice F. Twin studies in pediatric depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15:869–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin B read PDL updated: 17 J 2020 ~2 min. What are the Risk Factors for Depression? 2016. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://www.psychcentral.com/lib/what-are-the-risk-factors-for-depression .

- 21.Goodyer I, Wright C, Altham P. The friendships and recent life events of anxious and depressed school-age children. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 1990;156:689–98. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pine DS, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Brook JS. Adolescent life events as predictors of adult depression. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Child Maltreatment Among Asian Americans: Characteristics and Explanatory Framework-Fuhua Zhai, Qin Gao. 2009. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://journals-sagepub-com.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/doi/10.1177/1077559508326286 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hofstede G. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Cult Consequences Comp Values Behav Inst Organ Nations. 2001. Available from: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/unf_research/53 .

- 25.Oyserman D, Lee S. Priming “Culture”: Culture as Situated Cognition. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang WC, Wong WK, Koh JBK. Chinese values in Singapore: Traditional and modern. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2003;6:5–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ang RP, Huan VS. Academic expectations stress inventory: Development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66:522–39. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang WC, Koh JBK. A measure of depression in a modern Asian community: Singapore. Depress Res Treat 2012. 2012:691945. doi: 10.1155/2012/691945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magiati I, Ponniah K, Ooi YP, Chan YH, Fung D, Woo B. Self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms in school-aged Singaporean children. Asia-Pac Psychiatry. 2015;7:91–104. doi: 10.1111/appy.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramli M, Adlina S, Suthahar A, Edariah AB, Mohd Ariff F, Narimah AHH. Depression among Secondary School Students: A comparison between urban and rural populations in a Malaysian community. Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2008;18:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peh CX, Shahwan S, Fauziana R, Mahesh MV, Sambasivam R, Zhang Y, et al. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;67:383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong SS, Lim T. Hope versus optimism in Singaporean adolescents: Contributions to depression and life satisfaction. Personal Individ Differ. 2009;46:648–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y, Ho R, Lim TK, Kuan WS, Goh DYT, Mahadevan M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in Asian adolescent asthma patients and the contributions of neuroticism and perceived stress. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2014;55:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeo SC, Jos AM, Erwin C, Lee SM, Lee XK, Lo JC, et al. Associations of sleep duration on school nights with self-rated health, overweight, and depression symptoms in adolescents: Problems and possible solutions. Sleep Med. 2019;60:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo JC, Lee SM, Lee XK, Sasmita K, Chee NIYN, Tandi J, et al. Sustained benefits of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep and well-being. Sleep. 2018;41 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy052. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mythily S, Qiu S, Winslow M. Prevalence and correlates of excessive Internet use among youth in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li D, Fung D, et al. Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e319–29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Picco L, Pang S, Shafie S, Vaingankar JA, et al. Stigma towards people with mental disorders and its components-A perspective from multi-ethnic Singapore. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26:371–82. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng TP, Lim LCC, Jin A, Shinfuku N. Ethnic differences in quality of life in adolescents among Chinese, Malay and Indians in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1755–68. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chong SA, Vaingankar J, Abdin E, Subramaniam M. The prevalence and impact of major depressive disorder among Chinese, Malays and Indians in an Asian multi-racial population. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coker TR, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Grunbaum JA, Schwebel DC, Gilliland MJ, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among fifth-grade students and its association with mental health. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:878–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woo BSC, Ng TP, Fung DSS, Chan YH, Lee YP, Koh JBK, et al. Emotional and behavioural problems in Singaporean children based on parent, teacher and child reports. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:1100–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ullsperger JM, Nikolas MA. A meta-analytic review of the association between pubertal timing and psychopathology in adolescence: Are there sex differences in risk? Psychol Bull. 2017;143:903–38. doi: 10.1037/bul0000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:765–94. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:133–44. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. Pubertal changes in hormone levels and depression in girls. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1043–53. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shansky RM, Glavis-Bloom C, Lerman D, McRae P, Benson C, Miller K, et al. Estrogen mediates sex differences in stress-induced prefrontal cortex dysfunction. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:531–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zahn-Waxler C, Crick NR, Shirtcliff EA, Woods KE. Developmental Psychopathology: Theory and Method. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. The origins and development of psychopathology in females and males; pp. 76–138. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Durbeej N, Sörman K, Norén Selinus E, Lundström S, Lichtenstein P, Hellner C, et al. Trends in childhood and adolescent internalizing symptoms: Results from Swedish population based twin cohorts. BMC Psychol. 2019;7:50. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of anxiety disorders in German adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:263–79. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson TJ, Stegge H, Miller ER, Olsen ME. Guilt, shame, and symptoms in children. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:347–57. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cox SJ, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS. The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:842–52. doi: 10.1037/a0019813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Seow E, Vaingankar JA, Shafie S, Shahwan S, et al. Prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and associations of adverse childhood experiences with mental illnesses: Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;103:104447. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Etter DJ, Rickert VI. The complex etiology and lasting consequences of child maltreatment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:S39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hopfinger L, Berking M, Bockting CLH, Ebert DD. Emotion regulation mediates the effect of childhood trauma on depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;198:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang EC. Does dispositional optimism moderate the relation between perceived stress and psychological well-being?: A preliminary investigation. Personal Individ Differ. 1998;25:233–40. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z, Wang Y, Mao X, Yin X. Relationship between hope and depression in college students: A cross-lagged regression analysis. Personal Ment Health. 2018;12:170–6. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satisfaction with Life and Hope: A Look at Age and Marital Status |SpringerLink. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03395574 .

- 61.Lawrence JM, Standiford DA, Loots B, Klingensmith GJ, Williams DE, Ruggiero A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressed mood among youth with diabetes: The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1348–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovacs M, Goldston D, Obrosky DS, Bonar LK. Psychiatric disorders in youths with IDDM: Rates and risk factors. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:36–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greenley RN, Hommel KA, Nebel J, Raboin T, Li S-H, Simpson P, et al. A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:857–69. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szigethy E, Levy-Warren A, Whitton S, Bousvaros A, Gauvreau K, Leichtner AM, et al. Depressive symptoms and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:395–403. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adolescent Changes in the Homeostatic and Circadian Regulation of Sleep. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2820578/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Lo JC, Ong JL, Leong RLF, Gooley JJ, Chee MWL. Cognitive performance, sleepiness, and mood in partially sleep deprived adolescents: The need for sleep study. Sleep. 2016;39:687–98. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baum KT, Desai A, Field J, Miller LE, Rausch J, Beebe DW. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:180–90. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The Prospective Association between Sleep Deprivation and Depression among Adolescents. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900610/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Pigeon W, Perlis M. Insomnia and depression: Birds of a feather? Int J Sleep Disord. 2007;1:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clarke G, Harvey AG. The complex role of sleep in adolescent depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:385–400. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan NY, Zhang J, Yu MWM, Lam SP, Li SX, Kong APS, et al. Impact of a modest delay in school start time in Hong Kong school adolescents. Sleep Med. 2017;30:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.School Start Times for Adolescents |American Academy of Pediatrics. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/3/642.short .

- 73.AMA supports delayed school start times to improve adolescent wellness |American Medical Association. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-supports-delayed-school-start-times-improve-adolescent-wellness .

- 74.Watson NF, Martin JL, Wise MS, Carden KA, Kirsch DB, Kristo DA, et al. Delaying middle school and high school start times promotes student health and performance: An american academy of sleep medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med JCSM Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med. 2017;13:623–5. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calder KE. Singapore. Brookings1AD. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/book/singapore-smart-city-smart-state/

- 77.Infocomm Usage-Households and Individuals. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]];Infocomm Media Dev. Auth. Available from: http: //www.imda.gov.sg/infocomm-media-landscape/research-and-statistics/infocomm-usage-households-and-individuals. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nie NH, Erbring L. The Digital Divide: Facing a Crisis or Creating a Myth? Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2001. Internet and society: A preliminary report; pp. 269–71. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weisz JR, Suwanlert S, Chaiyasit W, Weiss B, Achenbach TM, Walter BR. Epidemiology of behavioral and emotional problems among Thai and American Children: Parent reports for ages 6 to 11. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26:890–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198726060-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weisz JR, Sigman M, Weiss B, Mosk J. Parent reports of behavioral and emotional problems among children in Kenya, Thailand, and the United States. Child Dev. 1993;64:98–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rutter M, Cox A, Tupling C, Berger M, Yule W. Attainment and adjustment in two geographical areas. I--The prevalence of psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 1975;126:493–509. doi: 10.1192/bjp.126.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British child and adolescent mental health survey. 1999: The prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1203–11. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bird HR, Bravo M, Ramirez R, et al. The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: Prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:85–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sawyer MG, Arney FM, Baghurst PA, Clark JJ, Graetz BW, Kosky RJ, et al. The mental health of young people in Australia: Key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:806–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Mason WA, Hawkins JD, McCarty CA, McCauley E. Effects of childhood conduct problems and family adversity on health, health behaviors, and service use in early adulthood: Tests of developmental pathways involving adolescent risk taking and depression. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:655–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clark DL, Raphael JL, McGuire AL. HEADS4: Social Media Screening in Adolescent Primary Care. Pediatrics. 2018. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. p. 141. Available from: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/141/6/e20173655 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Goldenring JM, Cohen E. Getting into adolescent heads. Contemporary Pediatrics. 1988;5:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Feature.pdf. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.sma.org.sg/UploadedImg/files/Publications%20-%20SMA%20News/4810/Feature.pdf .

- 90.OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume I) 2019. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/5f07c754-en .

- 91.S'pore students beat peers from 26 countries in Pisa test on awareness of global issues, intercultural skills. TODAY online. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/spore-students-beat-peers-26-countries-pisa-global-competence-test .

- 92.hermes. Over half of International Baccalaureate top scorers from Singapore. Straits Times. 2016. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/over-half-of-international-baccalaureate-top-scorers-from-singapore .

- 93.Tan C. Private supplementary tutoring and parentocracy in Singapore. Interchange. 2017;48:315–29. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ang RP, Klassen RM, Chong WH, Huan VS, Wong IYF, Yeo LS, et al. Cross-cultural invariance of the Academic Expectations Stress Inventory: Adolescent samples from Canada and Singapore. J Adolesc. 2009;32:1225–37. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ho K.C, Yip J. |Youth.sg: State of Youth in Singapore, Singapore: National Youth Council, 2003, Print. Singap. Res. Nexus. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/srn/?publication=youth-sg-state-of-youth-in-singapore-singapore-national-youth-council-2003-print .

- 96.Chinese and European American Mothers'Beliefs about the Role of Parenting in Children's School Success-Ruth K, Chao. 1996. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022022196274002?journalCode=jcca .

- 97.Huang GH-C, Gove M. Confucianism, Chinese Families, and Academic Achievement: Exploring How Confucianism and Asian Descendant Parenting Practices Influence Children's Academic Achievement. In: Khine MS, editor. Science Education in East Asia: Pedagogical Innovations and Research-informed Practices. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stankov L. Unforgiving confucian culture: A breeding ground for high academic achievement, test anxiety and self-doubt? Learn Individ Differ. 2010;20:555–63. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stright AD, Yeo KL. Maternal parenting styles, school involvement, and children's school achievement and conduct in Singapore. J Educ Psychol. 2014;106:301–14. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang Q, Pomerantz EM, Chen H. The role of parents'control in early adolescents'psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007;78:1592–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bögels SM, Brechman-Toussaint ML. Family issues in child anxiety: Attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:834–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Parental Control of the Personal Domain and Adolescent Symptoms of Psychopathology: A Cross-National Study in the United States and Japan. [[Last accessed on 2020 May 31]]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15144488/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2005;70:1–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kube T, Rief W, Glombiewski JA. On the Maintenance of Expectations in Major Depression-Investigating a Neglected Phenomenon. Front Psychol. 2017;8:9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ang RP, Goh DH. Authoritarian parenting style in asian societies: A cluster- analytic investigation*. Contemp Fam Ther. 2006;28:131–51. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 1994;65:1111–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Branje S. Development of parent-adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Dev Perspect. 2018;12:171–6. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 2011;12:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Olds T, Blunden S, Petkov J, Forchino F. The relationships between sex, age, geography and time in bed in adolescents: A meta-analysis of data from 23 countries. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lowe CJ, Safati A, Hall PA. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:586–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lo JC, Lee SM, Teo LM, Lim J, Gooley JJ, Chee MWL. Neurobehavioral impact of successive cycles of sleep restriction with and without naps in adolescents. Sleep. 2017;40:zsw042. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw042. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sajjadi H, Kamal SHM, Rafiey H, Vameghi M, Forouzan AS, Rezaei M. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of depression among iranian adolescents. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:16–27. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stirling K, Toumbourou JW, Rowland B. Community factors influencing child and adolescent depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:869–86. doi: 10.1177/0004867415603129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cairns KE, Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, Jorm AF. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lim CG, Ong SH, Chin CH, Fung DSS. Child and adolescent psychiatry services in Singapore. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:7. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Social and Emotional Learning. Base. [[Last accessed on 2021 Apr 25]]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.sg/programmes/social-and-emotional-learning .

- 119.Chong WH, Lee BO. Social-emotional Learning: Promotion of Youth Wellbeing in Singapore Schools. In: Wright K, McLeod J, editors. Rethinking Youth Wellbeing: Critical Perspectives. Singapore: Springer; 2015. pp. 161–77. [Google Scholar]

- 120.REACH (WEST) [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.nuh.com.sg/our-services/Specialties/Psychological-Medicine/Pages/REACH-(WEST).aspx .

- 121.About REACH-Institute of Mental Health. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.imh.com.sg/clinical/page.aspx?id=1635 .

- 122.Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Oort FJ, Meijer AM. The effects of sleep extension and sleep hygiene advice on sleep and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:273–83. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Randler C, Bilger S. Associations among sleep, chronotype, parental monitoring, and pubertal development among German adolescents. J Psychol. 2009;143:509–20. doi: 10.3200/JRL.143.5.509-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Youth. Fei Yue. [[Last accessed on 2021 Apr 25]]. Available from: https://www.fycs.org/our-work/youth/

- 125.Ng SH, Tan NJH, Luo Y, Goh WS, Ho R, Ho CSH. A systematic review of youth and teen mental health first aid: Improving adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.SAMH YouthReach |Singapore Association for Mental Health: Mental Wellness for All. 2018. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.samhealth.org.sg/our-services/rehabilitation/samh-youthreach/

- 127.Silver Ribbon (Singapore)-Home. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 20]]. Available from: https://www.silverribbonsingapore.com/

- 128.TOUCH Youth Intervention |Gaming Addiction, Internet Addiction. [[Last accessed on 2021 Apr 25]]. Available from: https://www.touch.org.sg/about-touch/our-services/touch-youth-intervention-homepage .

- 129.Brennan PA, Le Brocque R, Hammen C. Maternal depression, parent-child relationships, and resilient outcomes in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1469–77. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:211–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Silk JS, Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Ryan ND, et al. Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological contexts. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:841–65. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pargas RCM, Brennan PA, Hammen C, Le Brocque R. Resilience to maternal depression in young adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:805–14. doi: 10.1037/a0019817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ngiam X, Kang Y, Aishworiya R, Kiing J, Law E. Child maltreatment syndrome: Demographics and developmental issues of inpatient cases. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:612–7. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wong P, How C, Wong P. Management of child abuse. Singapore Med J. 2013;54:533–7. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.The role of emotional responding and childhood maltreatment in the development and maintenance of deliberate self-harm among male undergraduates.-PsycNET. [[Last accessed on 2021 Mar 21]]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.8.1.1 .

- 136.Linehan MM. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nock MK, Teper R, Hollander M. Psychological treatment of self-injury among adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:1081–9. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Slee N, Spinhoven P, Garnefski N, Arensman E. Emotion regulation as mediator of treatment outcome in therapy for deliberate self-harm. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15:205–16. doi: 10.1002/cpp.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Whitlock J, Prussien K, Pietrusza C. Predictors of self-injury cessation and subsequent psychological growth: Results of a probability sample survey of students in eight universities and colleges. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.King DL, Delfabbro PH, Zwaans T, Kaptsis D. Sleep interference effects of pathological electronic media use during adolescence. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2014;12:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Liu Q-X, Fang X-Y, Yan N, Zhou Z-K, Yuan X-J, Lan J, et al. Multi-family group therapy for adolescent Internet addiction: Exploring the underlying mechanisms. Addict Behav. 2015;42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Compas BE, Connor-Smith J, Jaser SS. Temperament, stress reactivity, and coping: Implications for depression in childhood and adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:21–31. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Witvliet M, Brendgen M, van Lier PAC, Koot HM, Vitaro F. Early adolescent depressive symptoms: Prediction from clique isolation, loneliness, and perceived social acceptance. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:1045–56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]