Abstract

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy (EBP) for repeated suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury and Borderline Personality Disorder. There has been little research on the effectiveness or implementation of DBT via telehealth. However, literature has demonstrated that other EBPs delivered via telehealth are just as effective as in-person. DBT differs from these EBPs in complexity, inclusion of group sessions, length of treatment, and focus on individuals at high risk for suicide. The COVID-19 pandemic caused mental health care services across the country and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to transition to telehealth to reduce infection risk for patients and providers. This transition offered an opportunity to learn about implementing DBT via telehealth on a national scale. We conducted a survey of DBT team points of contact in VA (N=32) to gather information about how DBT via telehealth was being implemented, challenges and solutions, and provider perceptions. The majority reported that their site continued offering the modes of DBT via telehealth that they had offered in-person. The predominant types of challenges in transitioning to telehealth were related to technology on the provider and patient side. Despite challenges, most providers reported their experience was better than expected and had positive perceptions of patient acceptability. Skills group was the more difficult mode to provide via telehealth. Providers endorsed needing additional tools (e.g., means to get diary card data electronically). Multiple benefits of DBT via telehealth were identified, such as addressing barriers to care including distance, transportation issues, and caregiving and work responsibilities.

Keywords: Dialectical behavior therapy, telehealth

Background

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) (Linehan, 1993, 2015) is an evidence-based psychotherapy with more than 50 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). DBT is appropriate for those with repeated suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). A meta-analysis indicated that DBT reduced self-directed violence and reduced frequency of psychiatric crisis services (DeCou et al., 2019). Comprehensive DBT consists of four modes of treatment that generally last one year in outpatient settings – weekly individual therapy, weekly group skills training, weekly therapist consultation team, and as needed phone coaching. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DOD) clinical practice guideline for the treatment and management of suicidality recommends DBT for individuals with BPD and recent self-directed suicidal or non-suicidal violence (The Assessment and Management of Suicide Risk Work Group, 2019).

Research examining the implementation of DBT indicates that DBT is acceptable to providers and leadership (Herschell et al., 2009; Landes et al., 2017; Swales et al., 2012) and it has been adopted by a variety of mental health settings, including county mental health services, VA, other government health systems, and community mental health (Carmel et al., 2014; Flynn et al., 2020; Hazelton et al., 2006; Herschell et al., 2009; Landes et al., 2017). Documented barriers to implementation include staffing issues and turnover (Carmel et al., 2014; Landes et al., 2017), lack of administrative/leadership support (Carmel et al., 2014; Flynn et al., 2020; Swales et al., 2012), insufficient time to do DBT (Carmel et al., 2014), limited resources for training, difficulty meeting for therapist consultation team (Landes et al., 2017), and difficulty implementing phone coaching outside of business hours (Chugani & Landes, 2016; Landes et al., 2017). Facilitators to implementation include staff interest, knowledge, and experience (Landes et al., 2017); leadership support; team cohesion, communication, and climate; supervision (Ditty et al., 2015); and dedicated team members (Flynn et al., 2020). Within VA, DBT has been implemented most often in general mental health clinics and skills group has been the mode of treatment that has been predominantly offered (i.e., not all modes of treatment are implemented) (Landes et al., 2017). This is likely due to the ease of offering groups within clinics with limited resources, or because therapy groups are already commonly found in the VA (Landes et al., 2017).

To date, there has been limited research on the effectiveness or implementation of DBT via telehealth, in which care is delivered in real-time using videoconferencing. However, a growing body of literature has demonstrated via RCTs that other evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) delivered via telehealth are just as effective as in-person care; this includes treatments for depression (Behavioral Activation, Egede et al., 2015) and PTSD (Behavioral Activation and Therapeutic Exposure, Acierno et al., 2016; Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Morland et al., 2020; and Cognitive Processing Therapy, Morland et al., 2015). DBT differs from these EBPs in its complexity (e.g., four modes of treatment), inclusion of group sessions, length (one year versus approximately 12–20 sessions), and focus on individuals at high risk for suicide. Individuals in DBT are highly complex and often emotionally dysregulated. Inclusion of between-session phone coaching as a mode of treatment is also unique to DBT (Chapman, 2018; Linehan, 1993). This mode of DBT has always been delivered via “telehealth”, but the other modes are typically in-person.

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic caused mental health care services across the country and VA to transition to telehealth in order to reduce infection risk for both patients and providers (Connolly, Stolzmann, et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). Others have described their teams’ experience in transitioning DBT to telehealth as a result of COVID-19 in settings such as community mental health (O’Hayer, 2021) and a university training clinic (Hyland et al., 2021). Zalewski and colleagues (2021) surveyed DBT providers internationally (N=200) about the challenges and lessons learned in transitioning to telehealth during COVID-19. Participants rated how effectively they were able to translate DBT principles via telehealth from 1 (not at all effective) to 5 (extremely effective) for each mode: individual (3.73), skills group (3.42), phone coaching (4.27), and therapist consultation team (3.94). One of the challenges most frequently reported by their primarily US-based sample were patient therapy-interfering behaviors during individual and skills group sessions that are less likely to occur during in-person sessions, including avoiding sessions, logging off early, not using video, smoking or drinking, being in bed, falling asleep, and being more easily distracted. They also reported difficulty making the skills groups interactive, resulting in leading group to be less rewarding for therapists and less cohesion among group members. The lessons learned included applying DBT to oneself, sticking with DBT principles, providing telehealth-specific orientation to patients, deciding on what engaged behaviors look like during orientation, learning to maximize interactive capabilities of video conferencing platform, seeking feedback from patients, and seeking consultation outside of therapist consultation team regarding telehealth decisions (Zalewski et al., 2021).

DBT teams across VA transitioned to telehealth quite quickly, often within a matter of days. VA is a unique setting for this transition to telehealth given its pre-existing capabilities for telehealth and recent pushes for clinicians to use telehealth prior to the pandemic (Heyworth et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2020). This major transition to remote care across VA offered an opportunity to learn about implementing DBT via telehealth on a national scale.

We therefore sought to survey DBT teams in VA about their experiences delivering DBT via telehealth. It was important to assess provider attitudes and experiences, as providers can serve as the gatekeepers to telehealth use (Connolly, Miller, et al., 2020; Cowan et al., 2019; Whitten & Mackert, 2005). For example, if providers do not believe telehealth is high enough quality or easy enough to use, they may not recommend continuing to use it with their patients. The overall purpose of the survey was to collect information from VA providers about how they are providing DBT via telehealth, challenges and solutions they have encountered, their perception of patient acceptability, their opinions about DBT via telehealth, and plans for future (post-pandemic) use of telehealth for providing DBT.

Methods

Study Design

The overall study design was a one-time survey of DBT team points of contact in VA. The primary objective was to gather information about how DBT via telehealth was being implemented, challenges and solutions, and provider perceptions. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the appropriate VA institutional review boards.

Sampling Strategy

We used an existing virtual community of practice of DBT providers in VA for recruitment. The virtual community of practice is located on an internal SharePoint site. It includes a listing of all facilities within VA offering components of DBT, as well as the name and email for each facility’s point of contact (Landes et al., 2019). Each point of contact was emailed with an invitation to complete the survey on behalf of their team.

Data Collection Procedures

The research team used the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (Eysenbach, 2004) to guide development and data collection procedures in this Web-based survey. The survey was created and data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Harris et al., 2009, 2019) hosted by the VA Information Resource Center (VIReC).

Survey usability and technical functionality were tested in June 2020 before fielding. Testers reported no problems and gave feedback; minimal changes were made (e.g., wording edits for clarity, added a response option). Given the minimal changes, field testers’ responses were saved rather than asking them to complete the survey again. The survey was voluntary and not password protected or incentivized. Therefore, access was open to all DBT points of contact who were emailed the invitation directly. Recruitment and data collection of the final survey occurred from August through October 2020.

Measures

We developed a web-based survey about the use of DBT via telehealth in VA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Items were developed by experts in DBT and its implementation (SJL, MSH, LLM) and informed by an expert in telehealth (SLC). The survey topics included: technology used for each mode of DBT, changes made to each mode (if any), challenges in transitioning to telehealth, challenges specific to each mode and how these were being handled, tools and resources desired for providing DBT via telehealth, provider perspective on patient acceptability, and provider opinion about DBT via telehealth.

The survey included 47 items. Questions were grouped by category and the order of questions was not randomized. The survey used adaptive questioning, so that certain sections were conditionally displayed based on responses to other items to reduce number and complexity of the questions. For example, additional questions about skills group were only displayed if a participant indicated that their site provided skills group. Page breaks were used to reduce burden. The full survey can be found in Appendix 1.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis of survey responses was conducted using SAS software, Version 9.4. Template analysis (Hamilton, 2013) was used to analyze qualitative data obtained through open text questions. Template analysis involves developing a coding template to summarize themes identified in the data. A team member with qualitative coding experience (SJL) reviewed the data and used inductive coding to create template domains and categories (i.e., themes and sub-themes). She and another team member with qualitative experience (CMO) then summarized the content using that template. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Results

Description of Participating Sites

DBT points of contact at all 90 VA sites listed on an internal DBT virtual community of practice were emailed solicitations to participate in the survey. Emails from 10 sites were returned as undeliverable or the provider was no longer in that position and a replacement was unable to be identified. An additional four sites indicated they no longer had a DBT program. Forty-two percent of the remaining sites solicited (32/76) responded to the survey, one of which had two separate DBT teams within it. The settings included general outpatient mental health (n=24), PTSD Care Team (n=4), and other (n=5). The category of other included one each of cross-clinic, addiction services, primary care mental health integration, women’s mental health, and residential women’s trauma program. See Table 1 for a description of modes offered at each site before COVID-19 and via telehealth due to COVID-19.

Table 1.

Percentage of sites offering each mode of DBT prior to COVID-19 in-person and via telehealth during COVID-19.

| Mode | % of Sites Offering In-Person Prior to COVID-19 | % of Sites Offering via Telehealth during COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Skills group | 100% | 97% |

| Individual | 91% | 91% |

| Therapist consultation team | 85% | 76% |

| Phone coaching | 79% | N/A* |

Note: The survey only asked about in-person modes that were then offered via telehealth during the pandemic. The format of phone coaching would not change.

Prior to the pandemic, providers reported that 0–15% of DBT individual and group therapy services at their site were being delivered via telephone or telehealth. All sites either began offering, or offered more, DBT services via telephone or telehealth due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the start of the pandemic, 90–100% of DBT individual and group therapy services were being delivered via telephone or telehealth.

Technology Used

Providers reported using a range of platforms for individual, skills group, and therapist consultation team. These included VA Video Connect (VA’s platform for telehealth), telephone, Webex, Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Doxy.me, Doximity, and FaceTime. The majority reported using VA Video Connect for individual and group sessions (85% and 82%, respectively). The majority reported using Microsoft Teams or Webex for therapist consultation team (33% and 24%, respectively).

Changes Made to DBT In Transition to Telehealth

In transitioning to telehealth, providers reported changes made to skills group, individual therapy, and consultation team at their site. The majority made no changes to the modes of treatment (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent of sites making changes to DBT modes.

| Changes Made | Skills Group | Individual Therapy | Consultation Team |

|---|---|---|---|

| No changes | 55% | 79% | 61% |

| Length of session | 9% | 0% | 3% |

| Frequency of sessions | 0% | 3% | 3% |

| Number of group leaders | 6% | N/A | N/A |

| Number of patients | 9% | N/A | N/A |

| Changes in content | 12% | 3% | N/A |

| Other | 18% | 9% | 9% |

Other changes for skills groups included updating informed consent and group rules documents to accommodate telehealth, adapting to not having a white board to teach with, delivery of materials (e.g., mailing skills workbooks to clients, sending PDF versions of materials), and not collecting materials directly from clients (e.g., not turning in diary cards or homework assignments). Other changes for individual therapy also included updating informed consent documents, delivery of materials (e.g., emailing diary cards), and formatting diary cards for ease of completion (e.g., changing to PDF). Other changes for consultation team included an increased focus on adhering to the structure and function of team and use of screensharing to keep organized.

Homework and Diary Card Review

To review homework and diary cards, the majority of providers reported using verbal review (88%), followed by holding the diary card up to the camera (61%), secure message or email (55%), screen sharing (42%), use of an app for diary cards (18%), and other (3%).

Attendance and Dropout Policies

Eighteen percent of providers reported their site making changes to DBT’s four-miss rule, in which patients are considered to have dropped out of DBT after missing four consecutive appointments of any one treatment mode (i.e., missing four groups in a row, missing four individual appointments in a row). Examples of changes made included suspending the rule for the first month while ensuring that all patients were telehealth capable, being “looser overall” about the rules due to the additional stress of the pandemic, and allowing sooner return to DBT after being discharged due to missed appointments. One site had previously offered DBT via telehealth services prior to the pandemic and had required patients to attend at least one session in-person every four weeks; they removed the in-person attendance requirement.

Phone Coaching

Fifty-four percent of providers with sites utilizing the phone coaching modality reported noticing no changes to the use, frequency, or content of the calls. Themes identified in the changes described by the remaining 46% included changes in the frequency and content of calls. More than half of those who noted changes in frequency reported an increase in frequency of calls. Two providers reported decreased use. One provider identified a facilitator to phone coaching that occurred as a result of the pandemic: team members receiving VA cell phones. They described, “Our team members receiving VA cell phones made phone coaching more accessible - prior to that, it was difficult because providers would have to call into their VA voicemail multiple times a day, creating substantial delays in returning veterans’ calls.”

Changes in the content of calls included pandemic-related reasons for calling, such as increased stress due to COVID-19, increased suicidal behavior or risk due to that stress, distress over not being able to practice skills given social distancing, and dysregulation due to technical difficulties. One provider stated, “There has been an increase in the use of phone coaching (distress has generally appeared to increase in the context of the pandemic). In addition, phone coaching has been used to address emotional reactions to technology difficulties, as well as problem-solving.” Another change in content of calls was an increase in coaching related to race-based trauma. One provider stated, “We are now more likely to have coaching calls related to race-based trauma and dysregulation since the death of George Floyd. Overall, though, it seems that coaching needs have been reduced with people having fewer situations outside of their homes to navigate.”

Challenges in Transition to Telehealth

Provider Challenges

Providers endorsed challenges their site experienced in transitioning to telehealth (see Table 3). Forty-eight percent reported that these challenges resolved over time.

Table 3.

Provider challenges in transitioning to telehealth.

| Challenge | Percent of Settings |

|---|---|

| Technology failures | 82% |

| Providers spending time providing technical support or troubleshooting technology versus providing therapy | 79% |

| Difficulty with scheduling system | 52% |

| Provider unease with technology | 39% |

| Provider lack of technical skills | 36% |

| Other challenges* | 36% |

| Difficulty with communication and/or support from leadership about telehealth policies | 24% |

| Lack of needed equipment (e.g., webcams, headsets) | 21% |

| Confusion regarding how to document or code encounters in electronic medical record | 18% |

| Concern or confusion about getting full workload credit for encounters | 15% |

| No challenges | 3% |

Other challenges were categorized as time challenges (e.g., longer time for documentation due to addition of a new telehealth template), facility/policy challenges (e.g., changes in telework policies), therapy skill challenges (e.g., difficulty building rapport), and team connection challenges (e.g., missing seeing team members in person).

Patient Challenges

Providers also rated how often a variety of patient challenges occurred when providing skills group and individual therapy via telehealth at their site; see Figure 1. Fourteen items were grouped into three categories; Patient’s Behavior (8 items; i.e., engaging in other activities during group), Patient’s Technology (4 items; i.e., not having sufficient or stable internet), and Patient’s Environment (2 items; i.e., being interrupted by people or pets in their environment). See full survey in Appendix 1 for all items. Participants indicated how frequently each item occurred on a 5-point scale; never, rarely, occasionally, moderate, or a great deal. The most frequently occurring challenges were in the Patient’s Technology category and included patients not having sufficient or stable internet, audio problems, other technical difficulties, and not turning on their camera. More patient challenges were reported in skills group versus individual therapy.

Figure 1.

Frequency of provider-reported patient challenges during DBT individual therapy and skills group via telehealth.

Solutions

Providers described how their team and/or providers were addressing therapy interfering behaviors (TIBs; e.g., logging off early) in skills group and individual sessions. For both modes, most providers reported using the same strategies as in-person (e.g., using chain analysis in the session, highlighting the issue, encouraging use of skills). For both modes, a major theme was to update rules for telehealth, orient patients to the rules, and remind patients of rules. One provider described, “We have updated our Group Rules for VVC platform. These have been discussed and reviewed in group. Skills trainers have offered gentle reminders/requests during session to maintain privacy for some, and trainers have encouraged troubleshooting technology difficulties with the help desk when needed. We typically address TIBs during individual therapy sessions.” Another theme in responses was use of technology and the availability of technology support, such as the ability to request VA iPads and place technology support consults. A related theme was use of strategies specific to telehealth to deal with difficulties, such as using the mute button in skills group. A provider described a combination of strategies to deal with patient challenges:

“We’ve added an orientation to VVC group at the beginning of our mindfulness module to emphasize VVC-specific guidelines, expectations, provide trouble-shooting [for] tech concerns [et cetera]. We’ve been able to secure VA-issued iPads for several [patients] who needed them ... Individual therapists will address group interfering behaviors in [patients’] individual sessions through chains, [et cetera]. We’ve used the mute button liberally to cut down on ambient noise and when needed to block TIBs when verbal direction has failed (e.g., ‘Thanks again for sharing, I’m going to go ahead and mute your mic so we can check in with...’). … We also have had to use radical acceptance and become more flexible around non-therapy destroying issues (e.g., [patient] sitting in their bed for group if that’s their only private space).”

Tools or Resources Needed

Using a list of possible tools or resources, providers endorsed which ones their team or providers need or would want for providing DBT via telehealth. Adapting the tools, especially the forms and documents, that are critical to DBT to a telehealth setting were at the top of the list (e.g., diary card). See Table 4.

Table 4.

Tools and resources desired for providing DBT via telehealth.

| Tools or Resources | Percent Endorsed |

|---|---|

| Easy way to get diary card data electronically | 97% |

| Fillable versions of skills worksheets | 88% |

| White board (real or virtual) for teaching on video | 82% |

| Increased access to necessary equipment for patients (e.g., tablets, laptops, webcams, VA iPads) | 55% |

| Electronic versions of skills manuals | 55% |

| Other | 9% |

Perceived Acceptability and Appropriateness

Patient Acceptability

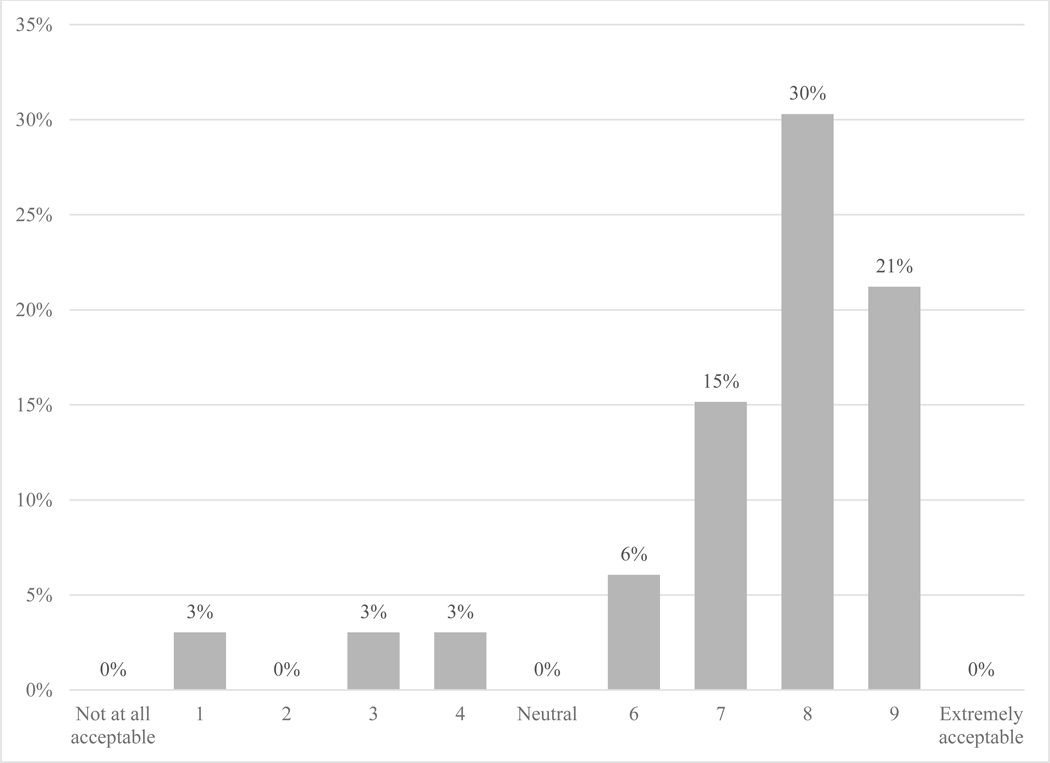

Providers rated their perception of patient acceptability of receiving DBT via telehealth; see Figure 2. Nine percent rated their perception of patient acceptability negatively (4 or lower); 73% rated it positively (6 or higher).

Figure 2. Provider-reported perception of patient acceptability of receiving DBT via telehealth.

Appropriateness

Providers were asked whether certain types of patients would not be appropriate for DBT via telehealth. Responses were grouped into categories that included patients with technology difficulty or insufficient access to video-enabled devices or internet, patients with difficulty complying with rules (e.g., noncompliance with confidentiality), and those with location difficulties (e.g., no private location to participate, housing insecurity). Providers also identified patient problems that might make them less appropriate for DBT via telehealth. These included patients with significant dysregulation (e.g., needing help in session to regulate), trouble connecting with therapists, those at high risk of suicide or NSSI, and those with other diagnoses (e.g., psychosis, social phobia).

Providers reported what challenges, if any, their team or providers have encountered when delivering DBT to patients at high risk for suicide via telehealth. Some identified that there were no significant challenges via telehealth or that they were the same challenges encountered when managing high risk patients in person. Others endorsed challenges including more difficulty in confirming a high risk patient’s location (e.g., patients not disclosing current location), more difficulty in lethal means counseling (e.g., not being able to hand a patient a gun lock), and having a hard time interpreting non-verbal behavior. One provider said, “Nothing different than in person care. The only thing I could imagine being different is if we were to agree to hold or dispose of lethal means for a patient, which is harder to do without in-person meetings.” An additional challenge was provider anxiety. As one provider stated, “Largely, the greatest challenge has been provider-related anxiety regarding suicidal patients being able to sign off/disappear/lie about their location.... Though the challenges are similar to in-person, providers have less of a sense of control or feel less effective in responding.”

Provider Opinion of DBT Via Telehealth

Experience Compared to Expectation

Providers rated their experience delivering DBT via telehealth as compared to their initial expectations; see Figure 3. The majority (57%) reported their experience was better than expected (6 or higher), while 21% reported it was about the same as their expectations and 21% reported it was worse than expected (4 or lower).

Figure 3.

Participants’ rating of their team’s or providers’ experience delivering DBT via telehealth compared to expectations.

Perceived Effectiveness of Modes

Providers rated how effective they perceived each mode of DBT to be when delivered in-person and via telehealth on a scale from 1 (not at all effective) to 10 (extremely effective). Provider ratings of the effectiveness of in-person skills group averaged 9.53 (SD=0.61); ratings ranged from 8 to 10. Provider ratings of the effectiveness of skills group via telehealth averaged 7.09 (SD=2.01); ratings ranged from 2 to 10. Provider ratings of the effectiveness of in-person individual averaged 9.38 (SD=0.81); ratings ranged from 7 to 10. Provider ratings of the effectiveness of individual via telehealth averaged 7.47 (SD=1.87); ratings ranged from 3 to 10. Provider ratings of the effectiveness of in-person therapist consultation team averaged 9.15 (SD=1.38); ratings ranged from 7 to 10. Provider ratings of the effectiveness of therapist consultation team via telehealth averaged 7.28 (SD=1.76); ratings ranged from 4 to 9.

Benefits of DBT Via Telehealth

Providers described the main benefits of delivering DBT via telehealth. These were improved access and reduced barriers to care, increased consistency of attendance to treatment, and safety during the pandemic. Several providers reported that removal of travel to attend DBT was a significant benefit for those with transportation troubles, patients who live farther away from VA or in more rural areas, or those who work, as they would be able to take less time off to attend. Others noted that the telehealth option reduced barriers related to lack of childcare, elder care, or other caregiving barriers. One provider described multiple benefits of DBT via telehealth, “We can reach people in rural areas or who live a long way from our VA. It cuts down on no-shows. Mostly convenient for patients and providers.”

Downsides of DBT Via Telehealth

Providers described the main downsides of delivering DBT via telehealth. The two most common categories were technology troubles and less personal connection. One provider stated, “A strong therapeutic relationship is so central to DBT and I feel like I am conducting DBT with a hand tied behind my back.” Related to personal connection, some participants reported that group is harder, especially with allowing for connection between group members.

Future DBT Via Telehealth Plans

Providers rated the likelihood of their site providing DBT via telehealth after the COVID-19 pandemic; see Figure 4. For skills group, 53% indicated it was moderately to extremely likely they would continue providing skills group via telehealth. For individual therapy, 86% indicated it was moderately to extremely likely that they would continue providing individual therapy via telehealth. For therapist consultation team, 68% indicated it was moderately to extremely likely that they would continue providing consultation team via telehealth.

Figure 4.

Providers’ rating of likelihood of their program continuing each mode of DBT via telehealth after COVID-19.

Discussion

The majority of providers reported that their site continued offering the modes of DBT via telehealth that they were offering in-person before the pandemic. In addition, there were minimal changes to how modes of DBT were provided in the transition to telehealth. The changes that were made were primarily focused on adapting to a new method of providing treatment (e.g., updated rules for telehealth).

The types of challenges reported in transitioning to telehealth (i.e., predominantly related to technology on the provider and patient side) make sense given that this was a rapid transition to telehealth in the midst of a global pandemic. Providers and teams acted quickly to continue providing DBT services and dealt with issues as they arose (i.e., this was not a transition with time for advanced planning). In addition, the healthcare system was adjusting to an increase in telehealth appointments, which taxed the system. National daily video and phone use for mental health appointments increased by 556% and 442%, respectively in the six weeks following the pandemic declaration within VA (Connolly, Stolzmann, et al., 2020).

Despite these challenging conditions, most providers (57%) reported that their experience transitioning to telehealth was better than expected. In addition, nearly three-quarters of providers (73%) reported positive perceptions of the acceptability of telehealth for DBT patients. These results align with findings from a recent systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconference demonstrating that providers have positive attitudes toward telemental health despite identifying multiple challenges or drawbacks (Connolly, Miller, et al., 2020).

However, providers rated their perception of the effectiveness of individual therapy, skills group, and consultation team as higher in-person versus via telehealth. For all three modes, the average ratings for telehealth, while in the effective range, showed more variability and were consistently lower than for in-person. These findings are consistent with prior literature in which providers have tended to rate in-person care as higher than telehealth with regards to effectiveness and/or satisfaction (Connolly, Miller, et al., 2020; Ertelt et al., 2011; Mayworm et al., 2020; Ruskin et al., 2004). However, provider ratings of telehealth have also been found to be lower than patient ratings on average (Connolly, Miller, et al., 2020; Cruz et al., 2005; Shulman et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2018), emphasizing the need for future research that captures patient perspectives on the effectiveness and acceptability of DBT delivered via telehealth.

As shown in Figure 4, almost half of the sample reported that they are “a little bit likely” or “not at all likely” to continue skills group via telehealth post-pandemic. Providers identified more frequent patient challenges in skills group as well, such as not turning on their camera or technology challenges. This is similar to challenges reported by Zalewski and colleagues (2021). These challenges are likely harder to address in a group setting compared to an individual session. This is an important finding that speaks to the complexity of running groups via telehealth and is consistent with prior literature demonstrating that patients had poorer satisfaction ratings for group therapy delivered via telehealth as compared to in-person treatment (Jenkins-Guarnieri et al., 2015).

High percentages of providers endorsed needing additional tools or resources to support them in providing DBT via telehealth. Almost all (97%) identified needing an easy way to get diary card data electronically. Many providers have created fillable PDF forms and diary cards that patients can complete electronically and either screenshare or send to their provider via secure messaging. This removed the need for a printed paper diary card to be transmitted back and forth. Others have generated other creative solutions for receiving diary cards in electronic format (e.g., patients taking photos and sending them via secure message). While many veterans choose to use VA’s secure messaging system to communicate with their providers; others do not. DBT diary card apps also exist, but none currently allow for seamless data transfer between patient and provider via a VA-approved encrypted online portal. Current work in VA is seeking to address these challenges (e.g., continued development and marketing of VA’s secure messaging portal and integrating additional patient tools within existing mobile applications). Solving these issues and creating the tools and resources requested by providers will be important to sustain the delivery of DBT via telehealth for the long term; if a provider cannot easily incorporate diary cards and worksheets into care, telehealth may not be viewed as a feasible mode of DBT delivery.

Given these challenges, what made the transition possible for a complex, multi-modal treatment with a high-risk patient population? The context of VA likely contributed to sites’ ability to transition to telehealth for DBT. VA already has existing infrastructure for telehealth across the national healthcare system, and had established a pre-pandemic goal to expand telehealth capabilities, given that it is not subject to some interstate licensure regulations and reimbursement restrictions experienced in the private sector (Connolly, Stolzmann, et al., 2020; Rosen et al., 2020). As identified by providers, VA also has services focused on addressing patient technology challenges, such as the Digital Divide Consult. The Digital Divide Consult was designed to “bridge the digital divide” for veterans who do not have internet access or a video-capable device to support telehealth. Services offered through this consult include, but are not limited to, VA loaned internet-connected devices (and connected device set-up support), support for mobile telehealth connectivity, and access to telehealth sites in the community (Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d.). This consult was piloted and then offered nationally in 2020. These resources may not be available in other healthcare systems.

Providers reported multiple benefits of DBT via telehealth, such as addressing barriers to care including distance, transportation issues, and caregiving and work responsibilities. They reported being able to reach veterans who were not previously able to attend DBT in person. These benefits may help motivate providers to sustain DBT via telehealth beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. That being said, providers endorsed technical challenges as being the largest barrier to DBT via telehealth, suggesting that additional work must be done to streamline telehealth processes and reduce the amount of time spent troubleshooting technologies during clinical sessions to sustain DBT via telehealth for the long term (e.g., conducting test calls, improving broadband connectivity in remote areas, optimizing homework and diary card transfer).

A major limitation of this survey is that it did not include standardized measures of DBT telehealth implementation, as such measures do not exist to our knowledge. The survey was not accompanied by qualitative interviews, which could have provided more depth of knowledge. We did not assess patients’ perspectives directly, which is a critical limitation. Future work should directly assess patient experience of receiving DBT via telehealth, especially their experience of DBT skills groups. In addition, this survey was limited to VA providers. The results may not generalize to other health systems with different telehealth regulations related to reimbursement or provision of care across state lines. Finally, while other EBPs have evidence of similar effectiveness via telehealth, it will be important to gather additional data on the effectiveness of DBT via telehealth, as DBT is a multi-modal treatment for high risk clients that lasts one year. Data on DBT’s effectiveness via telehealth may also be important to share with providers to inform their attitudes regarding methods of DBT care provision.

The findings presented provide a valuable perspective on providers’ satisfaction and experiences providing DBT via telehealth, identifying both key strengths and areas for improvement to sustain this mode of care delivery for the long-term. Given these findings, we make several recommendations for organizations planning to implement and/or sustain DBT via telehealth. First, organizations and therapists will want to orient patients about the expectations about engaging in DBT via telehealth. For skills group, this should include clarifying expectations about engaging in behaviors likely to increase connection with other members (e.g., having camera on, staying mindful while others are talking, directly providing feedback or encouragement to other group members when appropriate). Second, therapists may need to adjust their style or methods of teaching DBT skills group to facilitate group member interaction. This could include role plays with each other, group brainstorming, and other methods that more actively engage group members or allow for socializing between group members to increase group cohesion. Third, for individual therapy, organizations and therapists will want to consider how to manage diary cards virtually; options might include use of a DBT diary card app, sending diary cards via secure messaging, or sharing diary cards visually via camera in session. Finally, organizations will want to consider revising their policies to align with a new method of providing treatment to provide guidance for therapists doing DBT via telehealth. Broadly, this data can inform implementation planning for DBT via telehealth, as it is likely that remote mental health care delivery will continue to be a popular option well beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Impact statement:

The transition to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic offered an opportunity to learn about implementing Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) via telehealth on a national scale in the Department of Veterans Affairs. In a survey of DBT team points of contact (N=32), the predominant challenges were related to technology, most reported their experience was better than expected, and they had positive perceptions of patient acceptability. Multiple benefits of DBT via telehealth were identified, such as addressing barriers to care including distance, transportation issues, and caregiving and work responsibilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was authored as part of the Contributor’s official duties as an Employee of the United States Government and is therefore a work of the United States Government. In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 105, no copyright protection is available for such works under U.S. Law. This project was supported by funding from the Behavioral Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) grant (QUE 20-026) awarded to the first author through the Department of Veteran Affairs. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration (VHA), or the United States Government.

References

- Acierno R, Gros DF, Ruggiero KJ, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Knapp RG, Lejuez CW, Muzzy W, Frueh CB, Egede LE, & Tuerk PW (2016). Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: A noninferiority trial of treatment delivered in person versus home-based telehealth. Depression and Anxiety, 33(5), 415–423. 10.1002/da.22476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel A, Rose ML, & Fruzzetti AE (2014). Barriers and solutions to implementing dialectical behavior therapy in a public behavioral health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(5), 608–614. 10.1007/s10488-013-0504-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL (2018). Phone Coaching in Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chugani CD, & Landes SJ (2016). Dialectical behavior therapy in college counseling centers: Current trends and barriers to implementation. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 30(3), 176–186. 10.1080/87568225.2016.1177429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SL, Miller CJ, Lindsay JA, & Bauer MS (2020). A systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconferencing. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 27(2), 1–19. 10.1111/cpsp.12311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SL, Stolzmann KL, Heyworth L, Weaver KR, Bauer MS, & Miller CJ (2020). Rapid increase in telemental health within the Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine and E-Health, tmj.2020.0233. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan KE, McKean AJ, Gentry MT, & Hilty DM (2019). Barriers to use of telepsychiatry: Clinicians as gatekeepers. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(12), 2510–2523. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz M, Krupinski EA, Lopez AM, & Weinstein RS (2005). A review of the first five years of the University of Arizona telepsychiatry programme. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 11(5), 234–239. 10.1258/1357633054471821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCou CR, Comtois KA, & Landes SJ (2019). Dialectical behavior therapy is effective for the treatment of suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 60–72. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Connecting veterans to telehealth care. https://connectedcare.va.gov/sites/default/files/telehealth-digital-divide-fact-sheet.pdf

- Ditty MS, Landes SJ, Doyle A, & Beidas RS (2015). It takes a village: A mixed method analysis of inner setting variables and dialectical behavior therapy implementation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(6), 672–681. 10.1007/s10488-014-0602-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, Acierno R, Knapp RG, Lejuez C, Hernandez-Tejada M, Payne EH, & Frueh BC (2015). Psychotherapy for depression in older veterans via telemedicine: A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(8), 693–701. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00122-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertelt TW, Crosby RD, Marino JM, Mitchell JE, Lancaster K, & Crow SJ (2011). Therapeutic factors affecting the cognitive behavioral treatment of bulimia nervosa via telemedicine versus face-to-face delivery. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(8), 687–691. 10.1002/eat.20874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. (2004). Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6(3), e34. 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn D, Joyce M, Gillespie C, Kells M, Swales M, Spillane A, Hurley J, Hayes A, Gallagher E, Arensman E, & Weihrauch M. (2020). Evaluating the national multisite implementation of dialectical behaviour therapy in a community setting: A mixed methods approach. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 235. 10.1186/s12888-020-02610-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AB (2013, December 11). Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, & REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelton M, Rossiter R, & Milner J. (2006). Managing the ‘unmanageable’: Training staff in the use of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Contemporary Nurse, 21(1), 120–130. 10.5172/conu.2006.21.1.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell A, Kogan J, Celedonia K, Gavin J, & Stein B. (2009). Understanding community mental health administrators’ perspectives on dialectical behavior therapy implementation. Psychiatric Services, 60(7), 989–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyworth L, Kirsh S, Zulman D, Ferguson JM, & Kizer KW (2020). Expanding access through virtual care: The VA’s early experience with Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 1(4). [Google Scholar]

- Hyland KA, McDonald JB, Verzijl CL, Faraci DC, Calixte-Civil PF, Gorey CM, & Verona E. (2021). Telehealth for dialectical behavioral therapy: A commentary on the experience of a rapid transition to virtual delivery of DBT. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, S107772292100047X. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Pruitt LD, Luxton DD, & Johnson K. (2015). Patient perceptions of telemental health: Systematic review of direct comparisons to in-person psychotherapeutic treatments. Telemedicine and E-Health, 21(8), 652–660. 10.1089/tmj.2014.0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, Rodriguez AL, Smith BN, Matthieu MM, Trent LR, Kemp J, & Thompson C. (2017). Barriers, facilitators, and benefits of implementation of dialectical behavior therapy in routine care: Results from a national program evaluation survey in the Veterans Health Administration. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(4), 832–844. 10.1007/s13142-017-0465-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, Smith BN, & Weingardt KR (2019). Supporting grass roots implementation of an evidence-based psychotherapy through a virtual community of practice: A case example in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(3), 453–465. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2019.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (2015). DBT skills training manual (Second edition). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Mayworm AM, Lever N, Gloff N, Cox J, Willis K, & Hoover SA (2020). School-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting: Efficiency and satisfaction with care. Telemedicine and E-Health, 26(4), 446–454. 10.1089/tmj.2019.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland LA, Mackintosh MA, Glassman LH, Wells SY, Thorp SR, Rauch SAM, Cunningham PB, Tuerk PW, Grubbs KM, Golshan S, Sohn MJ, & Acierno R. (2020). Home-based delivery of variable length prolonged exposure therapy: A comparison of clinical efficacy between service modalities. Depression and Anxiety, 37(4), 346–355. 10.1002/da.22979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland LA, Mackintosh M-A, Rosen CS, Willis E, Resick P, Chard K, & Frueh BC (2015). Telemedicine versus in-person delivery of cognitive processing therapy for women with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority trial. Depression and Anxiety, 32(11), 811–820. 10.1002/da.22397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hayer CV (2021). Building a life worth living during a pandemic and beyond: Adaptations of comprehensive DBT to COVID-19. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, S1077722921000146. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BS, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, McKee GB, & Watson JD (2020). The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in U.S. mental health care delivery. American Psychologist. 10.1037/amp0000722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CS, Morland LA, Glassman LH, Marx BP, Weaver K, Smith CA, Pollack S, & Schnurr PP (2020). Virtual mental health care in the Veterans Health Administration’s immediate response to coronavirus disease-19. American Psychologist. 10.1037/amp0000751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin PE, Silver-Aylaian M, Kling MA, Reed SA, Bradham DD, Hebel JR, Barrett D, Knowles F, & Hauser P. (2004). Treatment outcomes in depression: Comparison of remote treatment through telepsychiatry to in-person treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1471–1476. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman M, John M, & Kane JM (2017). Home-based outpatient telepsychiatry to improve adherence with treatment appointments: A pilot study. Psychiatric Services, 68(7), 743–746. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swales MA, Taylor B, & Hibbs RAB (2012). Implementing dialectical behaviour therapy: Programme survival in routine healthcare settings. Journal of Mental Health, 21(6), 548–555. 10.3109/09638237.2012.689435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Assessment and Management of Suicide Risk Work Group. (2019). VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for The Assessment and Management of Patients at Risk for Suicide (2.0; VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines, p. 142). Office of Quality, Safety and Value, VA/Office of Evidence Based Practice, US Army Medical Command. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADoDSuicideRiskFullCPGFinal5088919.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JF, Novins DK, Hosokawa PW, Olson CA, Hunter D, Brent AS, Frunzi G, & Libby AM (2018). The use of telepsychiatry to provide cost-efficient care during pediatric mental health emergencies. Psychiatric Services, 69(2), 161–168. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten PS, & Mackert MS (2005). Addressing telehealth’s foremost barrier: Provider as initial gatekeeper. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 21(4), 517–521. 10.1017/S0266462305050725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski M, Walton CJ, Rizvi SL, White AW, Gamache Martin C, O’Brien JR, & Dimeff L. (2021). Lessons learned conducting dialectical behavior therapy via telehealth in the age of COVID-19. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, S1077722921000432. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.