Abstract

Objective: This study was carried out to determine the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies adapted for sexual function concerns on women’s sexual function, sexual distress, and depression levels. Methods: For this meta-analysis study, a review was conducted by screening studies published in the last 10 years on PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost, Google Scholar, and YÖK National Thesis Center databases from February to May 2024. After this initial review, 11 studies were included in this study. Considering the study design, quality assessment tools developed by JBI were used to evaluate the risk of bias. CMA version 2 was used for data synthesis. Data were synthesized using meta-analysis and narrative synthesis methods. Results: In this meta-analysis, mindfulness-based cognitive therapies were found to be effective in improving sexual function in women, and a high level of heterogeneity was detected among studies (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.461, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.163 to 0.760; Z = 3.027, p = .002, I2 = 79.083). Additionally, it was also determined that mindfulness-based cognitive therapies were effective in reducing sexual distress in women (SMD = −0.352, 95% CI = −0.638 to −0.066; Z= −2.412, p = .016, I2 = 78.377). Finally, mindfulness-based cognitive therapies were also determined to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression in women (SMD = −0.217, 95% CI = −0.420 to −0.015; Z= −2.101, p = .036, I2 = 27.688). Conclusions: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapies were found to be effective in decreasing women’s sexual dysfunction and reducing levels of sexual distress and depression.

Keywords: Sexual dysfunction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, sexual distress, depression

Introduction

Sexual dysfunctions are defined as psychophysiological disorders that cause a significant decrease in sexual desire and arousal, negatively impacting individuals’ lives and being among the most significant sexual health problems (Tehrani et al., 2014).

Using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder is diagnosed when a woman meets at least three of six criteria for 6 months. These criteria include lack of interest in sexual activity (or no interest at all), significantly reduced interest in sexual activity, decrease in initiating sexual intercourse and/or responding to partner’s sexual advances, decreased pleasure during sexual activity, and lack of sexual/erotic thoughts and fantasies (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sexual dysfunction can significantly impact relationships and overall quality of life (Stephenson & Kerth, 2017; Stephenson & Meston, 2010), creating an urgent need for the development, analysis, and dissemination of effective treatments (Jaspers et al., 2016). The prevalence of sexual dysfunction varies by region, but it was reported to be present in 30% to 50% of women (Weinberger et al., 2019).

Sexual dysfunction can increase the risk of depression by raising emotional stress levels (Karakaş Uğurlu et al., 2020; Kılıç, 2019). Sexual dysfunction, especially among married women, can lead to disruption in marital and family relationships, which can in turn result in divorce, forming the basis of social problems (Yılmaz Karaman et al., 2021). In addition, many women have concerns such as embarrassment, anxiety, fear of stigma, and negative attitudes from healthcare professionals because of sexual health problems (Alomair et al., 2022; Madbouly et al., 2021).

Both pharmacological and nonpharmacological intervention methods are used in the treatment of sexual dysfunctions (Mirzaee et al., 2020). In the last 15 years, mindfulness-based cognitive therapies (MBCT) have been reported to be effective in treating various sexual difficulties in women, including genital pain and low sexual desire (Brotto & Basson, 2014; Paterson et al., 2017). However, the mechanisms by which mindfulness improves women’s sexual problems are not clear (Arora & Brotto, 2017). Mindfulness practices are derived from Eastern culture, most notably from the Buddhist tradition. Mindfulness is one of the fundamental assumptions of the 3,500-year-old Noble Eightfold Path of Buddha. These practices, regardless of the religious background of the originating culture, have been described as methods accessible to everyone and are used to increase self-awareness and reduce daily distress (Ludwig & Kabat-Zinn, 2008).

Mindfulness-based approaches aim to develop awareness of body sensations with acceptance, nonjudgment, and compassion (Brotto et al., 2023). Awareness refers to paying attention to one’s experiences in the present moment (The NICE Guídelíne on the Treatment and Management of Depressíon ín Adults, 2010). MBCT recognizes cognitive distortions, negative thoughts, and so on, but brings these thoughts into the present moment through acceptance (Felder et al., 2012). MBCT is recommended for couples and individuals with sexual dysfunction (Felder et al., 2012). Mindfulness can also be used to develop conscious attention toward sexuality to increase satisfaction in one’s sexual life (Brotto & Basson, 2014). The effects of awareness-based therapies on sexual dysfunction in women were examined in a meta-analysis conducted by Stephenson and Kerth (2017). In this meta-analysis, strong effects were observed in the areas of sexual arousal and sexual satisfaction, whereas moderate effects were observed in lubrication and orgasm and low effects were observed in sexual pain (Stephenson & Kerth, 2017).

This study aims to determine the effects of mindfulness-based therapies on sexual function, sexual distress, and depression levels in women. In contrast to the study carried out by Stephenson and Kerth (2017), the present study also examines psychological dimensions such as sexual distress and depression, aiming to evaluate the comprehensive effects of MBCT on women’s sexual health. In addition, moderator analysis was conducted in this study, an approach that differs from other studies.

Method

This study carried out in the form of a meta-analysis was designed by following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols) checklist (Moher et al., 2009). To reduce the risk of potential bias in this meta-analysis, literature review, article selection, and data extraction processes were independently conducted by the first and second researchers. These stages were then reviewed again by two researchers. The quality assessment of the studies included in this meta-analysis was conducted by the researchers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A research question should clearly define the participants (P: population), interventions (I: interventions), comparators (C: comparators), outcomes (O: outcomes), and study designs (S: study designs). These components of the research question are referred to as PICOS (Centre for Reviews & Dissemination, 2008; Gerrish & Lacey, 2010).

In this study, research was conducted based on the PICOS criteria.

P – Patient (study group): Women with sexual dysfunction

I – Intervention: MBCT

C – Comparison: No application of MBCT

O – Outcomes: Sexual function, depression, distress

S – Study design: Experimental and quasi-experimental studies published in Turkish and English

Letters to the editor, case reports, and systematic and traditional reviews were excluded from the scope of this study.

Search strategy

A search was conducted between February and May 2024 using the keywords “female sexual dysfunction,” “vaginismus,” “vulvodynia,” “vestibulodynia,” “dyspareunia,” and “mindfulness-based therapy (MBCT)” in accordance with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) on PubMed, EBSCOhost, Web of Science, YÖK National Thesis Center, and Google Scholar. Studies from the last 10 years were reviewed in order to refer to current literature.

Selection of studies

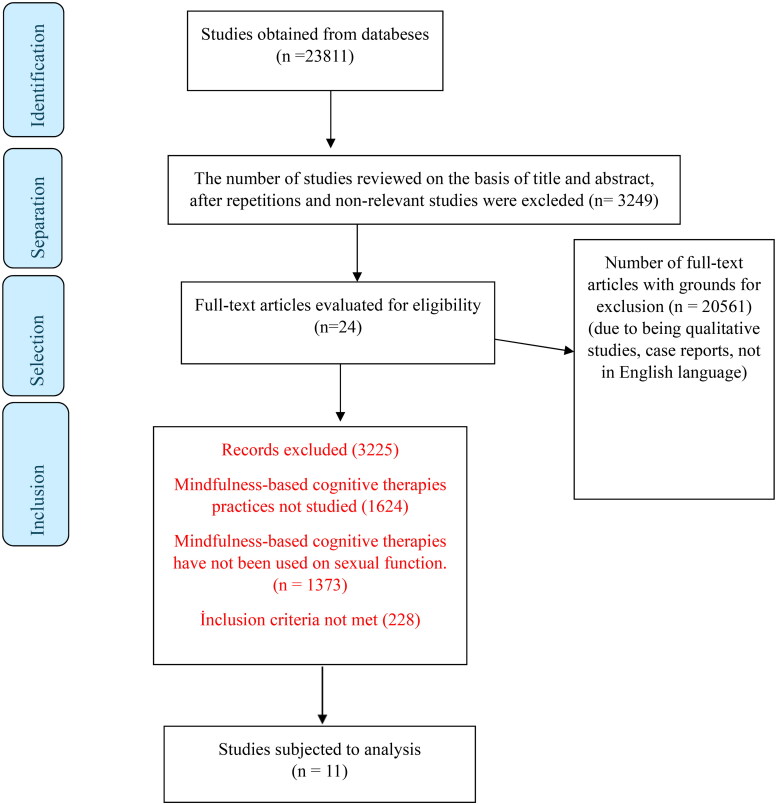

As a result of the screening, 23,811 records were collected. After removing duplicates and irrelevant studies, 3,249 records were reviewed to select titles and abstracts. As a result of this review, 24 studies were selected for full-text review. Then, the 24 articles that were accessed in full text were reviewed with consideration of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 11 studies were ultimately included in the analysis. The selection process of the articles is explained in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies according to PRISMA guidelines.

Data extraction

Researchers used a data extraction tool they developed gather data. This tool allowed for the organized compilation and incorporation of studies in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, collecting data (e.g., intervention and control groups related with the studies, mean final test scores, and standard deviation values) on authors and publication year of included studies, country in which the studies were carried out, sample size, patient group, scale used in the studies, main results, and quality score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and results of the included studies.

| Author/year | Study design | Country | Sample size | Scale | Outcomes | Patient population | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam et al., 2020 | Randomized control | Belgium | Experimental group: 35 Control group: 30 |

FSFI, FSDS | There was an increase in sexual function and a decrease in distress in women in both groups. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 11/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 2/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

| Brotto & Basson, 2014 | Randomized control | Canada | Experimental group: 68 Control group: 47 |

FSDS; FSFI; BDI | Sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, and overall sexual function in the intervention group significantly improved when compared to the control group. Sexual distress associated with sexual intercourse significantly decreased, as well as difficulties with orgasm and depressive symptoms, in both cases regardless of treatment. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 8/13 No: 1/13 Uncertain: 1/13 Not applicable: 3/13 |

| Brotto et al., 2015 | Randomized control | Canada | Experimental group: 62 Control group: 23 |

FSDS, BDI | Improvements were observed in pain and gender-related issues with treatment, but there was no change in pain during sexual intercourse. | PVD | Yes: 8/13 No: 2/13 Uncertain: 1/13 Not applicable: 2/13 |

| Brotto et al., 2019 | Randomized control | Canada | Experimental group: 59 Control group: 49 |

FSFI, FSDS-R | There was a significant interaction between group and time in terms of reported spontaneous pain; the improvements obtained with MBCT were at a higher level in comparison to those obtained with CBT. In terms of all other outcomes, there were similar significant improvements in both groups. | PVD | Yes: 9/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 3/13 Not applicable: 1/13 |

| Brotto et al., 2020 | Randomized control | Canada | Experimental group: 43 Control group: 45 |

FSFI | Women with primary PVD experienced greater improvement in the CBT condition, while women with secondary PVD experienced greater improvement in the MBCT condition. Women in shorter-term relationships experienced a greater improvement with MBCT, while women in longer-term relationships experienced greater improvement in sexual function with CBT. | PVD | Yes: 9/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 3/13 Not applicable: 1/13 |

| Brotto et al., 2023 | Randomized control | Canada | Experimental group: 70 Control group: 78 |

SIDI, FSDS-R, HAMD | The decrease in depression only mediated the decrease in sexual distress in the MBCT and psycho-education group. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 8/13 No: 1/13 Uncertain: 4/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

| Hucker & McCabe, 2015 | Randomized control | Australia | Experimental group: 26 Control group: 31 |

FSDS-R | There was a decrease in sexual distress in women in the treatment group. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 9/13 No: 1/13 Uncertain: 3/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

| Lin et al., 2019 | Randomized control | Iran | Experimentalgroup: 220 Control group: 220 |

FSFI, FSDS-R | There were improvements in sexual function, sexual distress, and intimacy in both the intervention group and the control group. The intervention group experienced greater improvement than the control group. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 11/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 2/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

| Omidvar et al., 2021 | Randomized control | Iran | Experimental group: 15 Control group: 15 |

SSQ | MBCT was shown to have a greater impact on sexual satisfaction dimensions when compared to CBT. | Vaginismus | Yes: 10/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 3/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

| Paterson et al., 2017 | Quasi-experimental | Canada | 26 participants | BDI-II | Depressive mood and míndfulness also significantly improved and medíated increases in sexual function. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 8/9 No: 0/9 Uncertain: 1/9 |

| Rashedi et al., 2022 | Randomized control | Iran | Experimental group: 35 Control group: 35 |

FSFI, FSDS-R | When compared to the control group, the mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral sexual therapy intervention significantly improved sexual desire, distress, self-expression, and function in the intervention group immediately after completion of the education sessions, as well as at 4 and 12 weeks later. | Sexual dysfunction | Yes: 11/13 No: 0/13 Uncertain: 2/13 Not applicable: 0/13 |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; FSDS = Female Sexual Distress Scale; FSDS-R = Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised; FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; HAMD = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; SIDI = Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory; SSQ = Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire; PVD = provoked vestibulodynia.

Research ethics

The present study is a meta-analysis based on studies published in the literature, and there is no need for ethical approval in our institution.

Assessment of methodological quality of studies

Considering the design of this research, the quality assessment of the studies included in this meta-analysis was conducted using quality assessment tools developed by JBI (The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in IBI Systematic Reviews, 2021). The assessment tools used in this study were selected based on the designs of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Thirteen assessment questions were used for randomized controlled trials (The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in IBI Systematic Reviews, 2021): (1) Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? (2) Was allocation to treatment groups kept confidential? (3) Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? (4) Were participants blind to treatment assignment? (5) Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? (6) Were outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment? (7) Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? (8) Was follow-up complete and, if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up described and analyzed adequately? (9) Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? (10) Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? (11) Were outcomes measured reliably? (12) Was appropriate statistical analysis used? (13) Was the trial design appropriate and were any deviations from the standard randomized controlled trial design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? For quasi-experimental studies, 9 questions were used (Tufanaru et al., 2017): (1) Is it clear in the study what is the “cause” and what is the “effect” (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? (2) Were participants included in any comparisons similar? (3) Have the participants included in any comparisons received similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? (4) Was there a control group? (5) Were there multiple measurements of the outcome, both before and after the intervention/exposure? (6) Was follow-up complete and, if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analyzed? (7) Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? (8) Were outcomes measured reliably? (9) Was appropriate statistical analysis used? The questions in these tools were evaluated with the options “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” and “not applicable.” The methodological quality was independently assessed by two authors, and a consensus was reached through discussion. The assessment results for each study included are presented in Table 1 as “Quality score.”

Data synthesis

CMA version 2 was used for the statistical calculations in the present study. The chi-square test and Higgins I2 statistic were used to assess heterogeneity in these studies. These tests help determine the degree of potential heterogeneity that could impact the reliability and generalizability of the meta-analysis results. Specifically, I2 values higher than 50% suggest significant differences in study results and indicate the presence of heterogeneity. These tests not only evaluate consistency in the studies but also give an idea of how generalizable the obtained results are. I2 values higher than 50% indicate that the meta-analysis results may vary due to different populations or study conditions, therefore suggesting that a random effects model may be more appropriate (Higgins et al., 2003).

The tau-squared statistic was used to evaluate the degree of variance and heterogeneity among studies in more detail. This statistic is useful in understanding how much of the heterogeneity is due to random variations. The tau-squared statistic allows for determining how much of the observed differences among studies are due to true heterogeneity and how much are due to random variance. This is important, especially when there are significant differences among studies and when the fixed-effects model may be insufficient. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to compare the effects of measurement tools used in different studies. Forest plots are prepared to visualize these SMD values. SMD allows for the calculation of an overall effect size by combining results from different studies. This approach enables a clear demonstration of consistency among studies and the magnitude of effects. Funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias. Funnel plot allows for visual detection of the presence of publication bias by evaluating symmetry between studies. Egger’s test, on the other hand, is a statistical test that evaluates this bias. Publication bias is important because it can negatively affect the generalizability of meta-analysis results. These tests enable the determination of the presence of possible bias and improve the accuracy of our results (Borenstein et al., 2021).

Results

In this meta-analysis, a total of 23,811 records were identified in the initial screening. After removing the duplicate records and reviewing the titles and abstracts, 24 articles were selected for full-text review. Following the evaluation of these articles considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 11 studies were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Ten of the studies included in the analysis are randomized controlled experimental studies, and one is a semi-experimental study incorporating pretest/posttest and control groups. The total sample size of the studies is 1,230 (intervention group: 633, control group: 571, single group: 26) (Table 1).

Given all studies included in this meta-analysis, it was determined that the evidence quality assessment tool covers more than 50% of the items (Table 1). This is important in terms of showing that the information presented in our meta-analysis is based on studies with acceptable levels of evidence quality.

Meta-analysis results on the impact of MBCT on sexual function in women

In this study, the presence of publication bias was determined using two methods: (a) funnel plot and (b) Egger’s regression test (Egger et al., 1997).

One important method revealing publication bias is the funnel plot, which indicates that studies in this dataset are distributed symmetrically at the top of the funnel (Figure 2). This indicates that there is no publication bias.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot reporting the results of studies on the effect mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on sexual function in women.

Using Egger’s method, the intercept (B0) was determined to be 1.02660, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) = 4.05203 to 6.10523; t = 0.49462; df = 6; and a two-tailed p value of .63845, indicating that the presence of publication bias ís not statistically significant (p = .63845).

Figure 3 illustrates the effect sizes, standard errors, variances, lower and upper limits, and forest plot of eight studies related to the impact of MBCT on sexual function in women. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory (SIDI), and Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire (SSQ) were used to evaluate sexual function in the studies. Considering the results reported in these studies, the meta-analysis revealed that MBCT was effective in improving women’s sexual function (SMD = 0.461, 95% CI = 0.163 to 0.760; Z = 3.027, p = .002; Figure 3). The collected data showed that MBCT generally has a significant effect in favor of the intervention group on women’s sexual function, and a high level of heterogeneity was found between the studies (I2 = 79.083%; p = .002).

Figure 3.

Forest plot on the effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on sexual function in women.

Meta-analysis results on the impact of MBCT on sexual distress in women

One of the most important methods of assessing publication bias, the funnel plot, indicates that there is no publication bias (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of studies reporting the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on sexual distress in women.

Publication bias among the studies included in this dataset was also determined using Egger’s method, and the intercept (B0) was determined to be −0.36608 with a 95% CI (−5.78321 to 5.05106); t = 0.16536, df = 6, and a two-tailed p value of .87409. This result indicates that the presence of publication bias is not statistically significant (p = .87409).

Figure 5 presents the effect sizes, standard errors, variances, lower and upper limits, and forest plot of eight studies on the impact of MBCT on sexual distress in women. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS) was used to assess sexual distress in these studies. Considering the results reported in these studies, the meta-analysis revealed that MBCT was effective in reducing sexual distress in women, and a high level of heterogeneity was found among the studies (SMD = −0.352, 95% CI = −0.638 to −0.066; Z= −2.412, p = .016, I2=78.134; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot on the effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on sexual distress in women.

Meta-analysis results on the impact of MBCT on depression levels in women

One of the most important methods of evaluating publication bias is the funnel plot, and studies in this dataset are distributed symmetrically at the top of the funnel (Figure 6). This indicates that there is no publication bias.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of studies reporting the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on the level of depression in women.

Publication bias among the studies included in this dataset was also determined using Egger’s method, and the intercept (B0) was determined to be −0.92517 with a 95% CI (−15.91835 to 14.06802); t = 0.26550; df = 2; two-tailed p value is .81549. This result indicates that the publication bias is not statistically significant (I2 = 27.688; p = .81549).

Figure 7 presents the effect sizes, standard errors, variances, lower and upper limits, and forest plot of four studies related to the impact of MBCT on the level of depression in women. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) were used to assess the level of depression in these studies. A meta-analysis was conducted considering the results reported in these studies, and it revealed that MBCT was effective in reducing the level of depression in women (SMD = −0.217, 95% CI = −0.420 to −0.015; Z= −2.101, p = .036; Figure 7). The collected data showed that MBCT generally has a significant effect in favor of the intervention group on the level of depression in women, and the studies included in the meta-analysis were analyzed using a fixed-effects model (I2= 79.083%; p = .036).

Figure 7.

Forest plot on the effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on the level of depression in women.

The average effect size of the intervention duration on sexual function in the present study was found to be 0.590 (95% CI = 0.357 to 0.824; p < .05). The between-study variance for the moderator of intervention duration in the study is statistically significant (p = .000). It was determined in the study that the intervention duration changes the effect size of MBCT on individuals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Moderator results on the impact of mindfulness-based cognitive therapies on sexual function in women.

| Moderator | No. of studies | Effect size | Standard error | Lower limit | Upper limit | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention period | ||||||

| 4 sessions | 2 | 0.728 | 0.153 | 0.427 | 1.028 | .000 |

| 8 sessions | 6 | 0.380 | 0.129 | 0.009 | 0.752 | .045 |

| Total | 8 | 0.590 | 0.119 | 0.357 | 0.824 | .000 |

| Country | ||||||

| Belgium | 1 | −0.320 | 0.250 | −0.811 | 0.171 | .201 |

| Canada | 4 | 0.338 | 0.130 | 0.083 | 0.592 | .009 |

| Iran | 3 | 1.043 | 0.382 | 0.294 | 1.792 | .006 |

| Total | 8 | 0.269 | 0.110 | 0.053 | 0.485 | .015 |

| Scale | ||||||

| FSFI | 7 | 0.341 | 0.117 | 0.112 | 0.571 | .003 |

| SSQ | 1 | 2.311 | 0.472 | 1.387 | 3.236 | .000 |

| Total | 8 | 0.455 | 0.113 | 0.233 | 0.678 | .000 |

FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; SSQ = Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire.

The average effect size values of the country in which MBCT was conducted on sexual function in the study was found to be 0.269 (95% CI: 0.053 to 0.485, p < .05). The between-study variance for the moderator of the country in which the intervention was conducted in the study is statistically significant (p = .015). It was determined in the study that the country in which the intervention was conducted changes the effect size of MBCT on individuals (Table 2).

The average effect size of the scale used in the present study on sexual function was found to be 0.455 (95% CI = 0.233 to 0.678; p < .05). The between-study variance for the scale moderator used in the present study is statistically significant (p = .000). It was determined that the scale used in this study changes the effect size of MBCT administered to individuals (Table 2).

Discussion

This meta-analysis comprehensively evaluated and summarized the existing evidence on MBCT used in the treatment of sexual dysfunctions in women.

Sexual function

In this study, results showed that there were statistically significant differences between the MBCT group and the control group in the FSFI total score table, FSDS, and depression measurement table. This suggests that MBCT could be used in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Similar to the literature review conducted by Banbury et al. (2021) on MBCT for sexual dysfunction, the overall effect size of this systematic review was found to be moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.461) (Cohen, 1988). Literature reviews showed that there is a limited number of studies that reliably evaluate the effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies in the treatment of sexual dysfunction (Jaderek & Lew-Starowicz, 2019). In a systematic review by Durna et al. (2020), it was observed that mindfulness-based therapies are effective in different types of female sexual dysfunction and that mindfulness-based online interventions were effective in improving overall sexual function levels and reducing the frequency of sexual problems (Durna et al., 2020). In the meta-analysis study carried out by Banbury et al. (2021), mindfulness-based therapies were found to have a positive effect on individuals experiencing sexual dysfunction (Banbury et al., 2021). In a systematic review carried out by Jaderek and Lew-Starowicz, (2019), it was stated that mindfulness-based therapies can be effectively used particularly in improving sexual arousal/desire and satisfaction and in the treatment of sexual dysfunction (Jaderek & Lew-Starowicz, 2019).

Following review of the literature, the present meta-analysis aimed to determine whether intervention duration changes the effects of interventions by including moderator analysis. Effects of MBCT on sexual function were found to be higher when the intervention duration was 4 weeks compared to 8 weeks (effect size = 0.590, standard error = 0.119, p < .001). This result shows that the duration of MBCT programs could be critical in terms of effectiveness. In clinical practice, keeping the number of sessions at a certain level can enhance the effectiveness of the program.

Sexual distress

The term “distress” is used to indicate the degree of personal dysphoría related to sexual functionality (Derogatis et al., 2008). In all studies included in this meta-analysis, FSDS was used to assess sexual distress. In this study, MBCT was found to be effective in reducing the level of sexual distress, and the overall effect size for the distress variable was determined to be low (Cohen’s d = −0.352) (Cohen, 1988). In a systematic review conducted by Durna et al. (2020), it was observed that MBCT played an effective role in improving the level of sexual distress. A meta-analysis conducted by Jaderek and Lew-Starowicz, (2019) reported that reducing negative cognitive schemas associated with sexual dysfunction is effective in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women.

Depression

Depression is characterized by a decrease in desire and interest, a depressive mood, a decrease or increase in sleep and appetite, psychomotor retardation, guilt, difficulty concentrating, decreased energy, and a tendency toward suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Results of clinical and epidemiological studies have reported that psychiatric medications have a 30% to 70% effect on sexual dysfunction in anxiety and depression (Fentahun et al., 2024). Further, 40% to 65% of individuals with severe depressive disorder were found to experience sexual dysfunction, and approximately 35% to 45% of individuals undergoing antidepressant treatment have general sexual dysfunction (Waldinger, 2015). MBCT aims to target depression by creating awareness of thoughts through practices that support metacognitive awareness (Solem et al., 2017).

BDI was used to assess the level of depression in most of the studies included in this meta-analysis. Our study found that MBCT is effective in reducing the level of depression, and the overall effect size for the depression variable was determined to be low (Cohen’s d = −0.217) (Cohen, 1988). In the meta-analysis conducted by Jaderek and Lew-Starowicz (2019), it was stated that MBCT can be effectively used in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in women because of its ability to reduce anxiety levels. In a similar manner, a meta-analysis by Reangsing et al. (2023) revealed that mindfulness-based interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer. At the end of the MBCT intervention, participants’ levels of anxiety (SMD = −0.70; 95% CI = −1.26 to −0.13; I2 = 69%) and depression (SMD = −0.65; 95% CI = −1.14 to −0.17; I2 = 75%) had decreased significantly (Reangsing et al., 2023). Another meta-analysis reported that participants’ levels of anxiety (SMD = −0.70; 95% CI = −1.26 to −0.13; I2 = 69%) and depression (SMD = −0.65; 95% CI = −1.14 to −0.17; I2 = 75%) decreased significantly after the MBCT intervention (Chen Chang et al., 2023).

Conclusion and recommendations

Sexual dysfunction among women is a common health problem that is often overlooked and has a negative impact on sexual health and satisfaction. The present study revealed that MBCT administered to women with sexual dysfunction was effective in improving sexual function and reducing sexual distress and depression levels. It was also found that MBCT implemented in four sessions was more effective. We believe that more studies should address the effectiveness of MBCT for sexual dysfunction in women.

Limitation of studies

Some studies included in the meta-analysis have small sample sizes (Adam et al., 2020; Hucker & McCabe, 2015; Omidvar et al., 2021; Paterson et al., 2017; Rashedi et al., 2022) and were carried out using a pretest/posttest design (Paterson et al., 2017). Additionally, blinding was not performed in the studies other than those by Lin et al. (2019) and Rashedi et al. (2022). These situations may reduce the strength of the evidence presented in the studies. Therefore, it is important to adhere to methodological standards in future studies. In addition, the limited number of meta-analyses evaluating the effectiveness of MBCT in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in the literature restricted the scope of our analysis.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References: The articles used in the meta-analysis are indicated with an asterisk (*).

- *Adam, F., De Sutter, P., Day, J., & Grimm, E. (2020). A randomized study comparing video-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with video-based traditional cognitive behavioral treatment in a sample of women struggling to achieve orgasm. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(2), 312–324. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alomair, N., Alageel, S., Davies, N., & Bailey, J. V. (2022). Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, perceptions and experiences of women in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. Ethnicity & Health, 27(6), 1310–1328. 10.1080/13557858.2021.1873251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. Inc. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arora, N., & Brotto, L. A. (2017). How does paying attention improvesexual functioning in women? A review of mechanisms. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(3), 266–274. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banbury, S., Lusher, J., Snuggs, S., & Chandler, C. (2021). Mindfulness-based therapies for men and women with sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 38(4), 533–555. 10.1080/14681994.2021.1883578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- *Brotto, L. A., & Basson, R. (2014). Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 43–54. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brotto, L. A., Basson, R., Smith, K. B., Driscoll, M., & Sadownik, L. (2015). Mindfulness-based group therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia. Mindfulness, 6(3), 417–432. 10.1007/s12671-013-0273-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Brotto, L. A., Bergeron, S., Zdaniuk, B., Driscoll, M., Grabovac, A., Sadownik, L. A., Smith, K. B., & Basson, R. (2019). A comparison of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia in a hospital clinic setting. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(6), 909–923. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brotto, L. A., Zdaniuk, B., Chivers, M. L., Jabs, F., Grabovac, A. D., & Lalumière, M. L. (2023). Mindfulness and sex education for sexual ınterest/arousal disorder: Mediators and moderators of treatment outcome. Journal of Sex Research, 60(4), 508–521. 10.1080/00224499.2022.2126815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brotto, L. A., Zdaniuk, B., Rietchel, L., Basson, R., & Bergeron, S. (2020). Moderators of ımprovement from mindfulness-based vs traditional cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of provoked vestibulodynia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(11), 2247–2259. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . (2008). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. University of York, York Publishing Services Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Chang, Y., Angie Tseng, T., Lin, G. M., Hu, W. Y., Wang, C. K., & Chang, Y. M. (2023). Immediate impact of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) among women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 331. 10.1186/s12905-023-02486-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. http://books.google.com.tr/ [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L., Clayton, A., Lewis-D'Agostino, D., Wunderlich, G., & Fu, Y. (2008). Validation of the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(2), 357–364. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durna, G., Ulbe, S., & Dirik, G. (2020). Mindfulness-based ınterventions in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction: A systematic review. Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 12(1), 72–90. 10.18863/pgy.470683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder, J. N., Dimidjian, S., & Segal, Z. (2012). Collaboration in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 179–186. 10.1002/jclp.21832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fentahun, S., Melkam, M., Tadesse, G., Rtbey, G., Andualem, F., Wassie, Y. A., Geremew, G. W., Alemayehu, T. T., Haile, T. D., Godana, T. N., Mengistie, B. A., Kelebie, M., Nakie, G., Tinsae, T., & Takelle, G. M. &. (2024). Sexual dysfunction among people with mental illness in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. PLoS One, 19(7), e0308272. 10.1371/journal.pone.0308272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish, K., & Lacey, A. (2010). The research process in nursing (6th ed., pp. 79–92, 188–198, 284–302). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hucker, A., & McCabe, M. P. (2015). Incorporating mindfulness and chat groups ınto an online cognitive behavioral therapy for mixed female sexual problems. Journal of Sex Research, 52(6), 627–639. 10.1080/00224499.2014.888388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaderek, I., & Lew-Starowicz, M. A. (2019). Systematic review on mindfulness meditatione based ınterventions for sexual dysfunctions. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(10), 1581–e1596. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, L., Feys, F., Bramer, W. M., Franco, O. H., Leusink, P., & Laan, E. M. (2016). Efficacy and safety of flibanserin for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA İnternal Medicine, 176(4), 453–462. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaş Uğurlu, G., Uğurlu, M., & Çayköylü, A. (2020). Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction and associated demographic factors in Turkey: A meta-analysis and meta-regression study. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(4), 365–382. 10.1080/19317611.2020.1819503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, M. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in healthy women in Turkey. African Health Sciences, 19(3), 2623–2633. 10.4314/ahs.v19i3.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lin, C.-Y., Potenza, M. N., Broström, A., Blycker, G. R., & Pakpour, A. H. (2019). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for sexuality (MBCT-S) improves sexual functioning and intimacy among older women with epilepsy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Seizure, 73, 64–74. 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, D. S., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2008). Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA, 300(11), 1350–1352. 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madbouly, K., Al-Anazi, M., Al-Anazi, H., Aljarbou, A., Almannie, R., Habous, M., & Binsaleh, S. (2021). Prevalence and predictive factors of female sexual dysfunction in a sample of Saudi women. Sexual Medicine, 9(1), 100277. 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaee, F., Ahmadi, A., Zangiabadi, Z., & Mirzaee, M. (2020). The effectiveness of psycho-educational and cognitive-behavioral counseling on female sexual dysfunction. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia, 42(6), 333–339. 10.1055/s-0040-1712483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group . (2009). Reprint—Preferred reporting ıtems for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Omidvar, Z., Bayazi, M. H., & Faridhosseini, F. (2021). Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy training and cognitive-behavioral therapy on sexual satisfaction of women with vaginismus disorder. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, Jul-Aug, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- *Paterson, L. Q. P., Handy, A. B., & Brotto, L. A. (2017). A pilot study ofeight-session mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adapted forwomen’s sexual interest/arousal disorder. Journal of Sex Research, 54(7), 850–861. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1208800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rashedi, S., Maasoumi, R., Vosoughi, N., & Haghani, S. (2022). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral sex therapy on ımproving sexual desire disorder, sexual distress, sexual self-disclosure and sexual function in women: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 48(5), 475–488. 10.1080/0092623X.2021.2008075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reangsing, C., Punsuwun, S., & Keller, K. (2023). Effects of mindfulness-based ınterventions on depression in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 22, 15347354231220617. 10.1177/15347354231220617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solem, S., Hagen, R., Wang, C. E., Hjemdal, O., Waterloo, K., Eisemann, M., & Halvorsen, M. (2017). Metacognitions and mindful attention awareness in depression: A comparison of currently depressed, previously depressed and never depressed individuals. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 94–102. 10.1002/cpp.1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, K. R., & Kerth, J. (2017). Effects of mindfulness-based therapies for female sexual dysfunction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Sex Research, 54(7), 832–849. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1331199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2010). Differentiating components of sexual well-being in women: Are sexual satisfaction and sexual distress independent constructs? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(7), 2458–2468. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, F. R., Farahmand, M., Simbar, M., & Afzali, H. M. (2014). Factors associated with sexual dysfunction; a population based study in Iranian reproductive age women. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 17, 679–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in IBI Systematic Reviews . (2021). Retrieved May 25, 2024, from http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- The NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults . (2010). Guideline 90, commissioned by the National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence, published by the British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Depression. [Google Scholar]

- Tufanaru, C., Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Campbell, J., & Hopp, L. (2017). Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In Aromataris E. & Munn Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. 72–134. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger, M. D. (2015). Psychiatric disorders and sexual dysfunction. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 130, 469–489. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00027-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, J. M., Houman, J., Caron, A. T., & Anger, J. (2019). Female sexual dysfunction: A systematic review of outcomes across various treatment modalities. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 7(2), 223-250. 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz Karaman, I. G., Sonkurt, H. O., & Gulec, G. (2021). Marital adjustment and sexual satisfaction in married couples with sexual functioning disorders: A comparative study evaluating patients and their partners. Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 34(2), 172–180. 10.14744/DAJPNS.2021.00135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]