Abstract

The liver is the most common anatomical site for hematogenous metastases of colorectal cancer, and colorectal liver metastases is one of the most difficult and challenging points in the treatment of colorectal cancer. To improve the diagnosis and comprehensive treatment in China, the Guidelines have been edited and revised several times since 2008, including the overall evaluation, personalized treatment goals and comprehensive treatments, to prevent the occurrence of liver metastases, improve the resection rate of liver metastases and survival. The revised Guideline includes the diagnosis and follow-up, prevention, MDT effect, surgery and local ablative treatment, neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy, and comprehensive treatment, and with advanced experience, latest results, detailed content, and strong operability.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00432-018-2795-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Liver metastases, Diagnosis, Comprehensive treatment, Guideline

Part I guidelines for diagnosis and treatment

The liver is the most common anatomical site for hematogenous metastases of colorectal cancer, more than 50% of colorectal patients develop liver metastases, and liver metastases are the most common cause of death in colorectal patients (Foster 1984). Therefore, liver metastases are among the most challenging points in the treatment of colorectal cancer. The median survival of untreated patients with colorectal liver metastases is only 6.9 months, while median survival of patients undergoing radical resection of liver metastases (or with no evidence of disease, NED) is 35 months, with 5-year survival rate of 30–57% (de Jong et al. 2009). Thus, a multidisciplinary team (MDT), utilizing comprehensive evaluations, individually planned treatment goals and active combined therapy, can reduce the risk of liver metastases and improve both the surgical resection rate and the 5-year survival rate (Timmerman et al. 2009).

To improve both the accuracy of diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of colorectal liver metastases in China, the work group develop guidelines for the diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of colorectal liver metastases. These guidelines were updated in 2018.

Note 1: The recommendations for diagnosis, prevention, surgery and other comprehensive treatments of colorectal liver metastasis provided in this guideline can be implemented by local hospitals in accordance with their actual situations. The recommendation level and evidence-based medicine classification presented in this paper is defined in Supplementary appendix 1.

Note 2: These guidelines do not include technologies and drugs that have not been approved for use in Mainland China.

Diagnosis and follow-up of colorectal liver metastases

Definitions of colorectal liver metastases

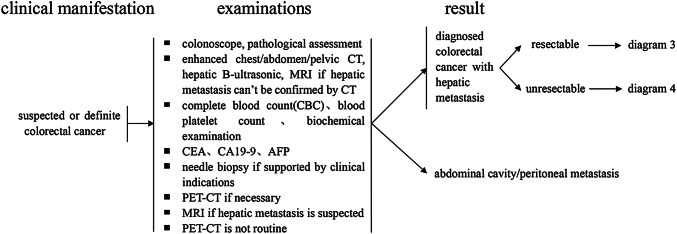

Based on the general international classification method, synchronous liver metastases refer to liver metastases discovered at the time or before primary colorectal cancer is definitively diagnosed. Liver metastases that occur after radical excision of the primary colorectal cancer are called metachronous liver metastases (Adam et al. 2015). To facilitate the formulation of diagnosis and treatment strategies, the descriptions in these guidelines are based on two parts: liver metastases discovered synchronously with the diagnosis of primary colorectal cancer and liver metastases discovered metachronously after radical excision of primary colorectal cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagnosis of hepatic metastasis when colorectal cancer is diagnosed

Routine diagnosis of liver metastases after a definitive diagnosis of colorectal cancer

For patients with a definitive diagnosis of colorectal cancer, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) should be examined, and evaluations of pathological staging and imaging, such as liver B-ultrasound and enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning, should be routinely performed to detect synchronous liver metastases. For patients with suspected liver metastases, serum AFP, liver ultrasonography and liver MRI examination should be performed (Coenegrachts et al. 2009). Enhanced MRI examinations using a liver cell-specific contrast agent are sometimes feasible when necessary. However, positron emission tomography (PET)–CT is not recommended as a routine examination, and it is to be used only when necessary (Delbeke and Martin 2004).

Needle biopsies of liver metastases should be limited and performed only when necessary (Jones et al. 2005).

During surgery for colorectal cancer, routine exploration of the liver must be performed to further exclude the possibility of liver metastases (Koshariya et al. 2007), and biopsy is recommended for suspicious liver nodules found during the operation.

Monitoring of liver metastases following radical excision of primary colorectal cancer

After curative resection of primary colorectal cancer, patients should be followed intensively to detect the occurrence of liver metastases.

A review of the medical history, physical examination and liver B-ultrasonography should be performed every 3–6 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of 5 years after the operation. After 5 years, they should be performed once each year.

Serum tumor markers (including CEA and CA19-9) should be examined every 3–6 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of 5 years after the operation. After 5 years, these examinations should be performed once each year.

For patients with stage II or III cancers, an enhanced CT scan of the chest/abdomen/pelvis has been suggested each year for 3–5 years after the operation and then every 1–2 years. For patients with suspected liver metastases, MRI should be performed, while routine PET-CT examination is not recommended.

The first colonoscopy should be performed in 1 year after the operation. If abnormalities are detected, it should be repeated in 1 year (Rex et al. 2006). A period of 3 years is suitable for patients without detected abnormalities, which can be subsequently extended to every 5 years after the initial examination. If the patient’s age of onset of colorectal cancer is less than 50 years, the frequency of colonoscopy examinations should be appropriately increased. Patients who present colonic obstruction and thus do not undergo a full colonoscopy should have their first colonoscopy in 3–6 months after surgery (Rex et al. 2006).

Follow-up for patients with NED of colorectal liver metastases

Intensive follow-up visits should be scheduled for patients with NED of colorectal liver metastases to determine whether liver metastases have recurred.

Based on tumor marker levels before the operation, it is suggested that tests for serum tumor markers, including CEA and CA19-9, should be performed every 3 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of 5 years. After 5 years, they should be performed once each year.

After surgery, enhanced CT of the chest/abdomen/pelvic cavity should be performed every 3–6 months for 2 years. It is suggested that MRI scans should be performed to support major clinical decisions, and a liver cell-specific contrast agent can be used for enhanced MRI examination when necessary. These examinations should then be performed every 6–12 months for a total of 5 years and once each year thereafter. Routine PET–CT examination is not recommended.

For additional follow-up, please refer to the guidelines on radical excision of primary colorectal cancer.

Biomarker testing in colorectal liver metastases

All patients with colorectal liver metastases are recommended to undergo RAS testing (at least KRAS exons 2, 3 and 4 and NRAS exons 2, 3 and 4), BRAF V600E mutation status testing, and DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene and microsatellite instability (MSI) testing.

Primary colorectal tumors and their liver metastases are mostly indistinguishable in terms of genetic status. Liquid biopsy can be considered when tumor tissue is not available for detection.

Prevention of colorectal liver metastases

Radical excision of primary colorectal cancer

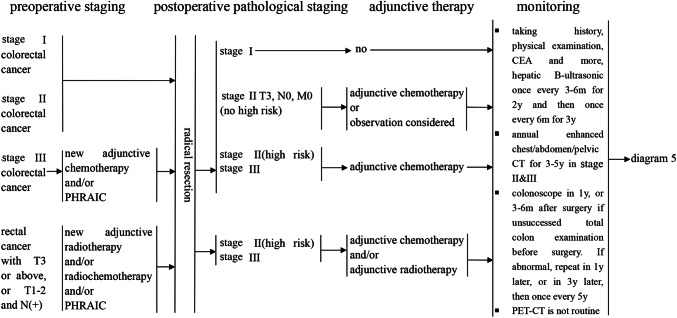

Radical excision is the most effective treatment to cure primary colorectal cancer (Okuno 2007), and it is essential to reduce the risk of metachronous liver metastases (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prevention of hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer

Radical excision of the primary colon cancer should perform complete mesocolic excision (CME), and radical excision of rectal cancer should perform total mesorectal excision (TME). Suspicious lymph nodes found during the operation that have been identified beyond the extent should be biopsied or removed.

Neoadjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer without liver metastasis (or other distant metastases)

Neoadjuvant therapy might eradicate subclinical metastatic foci before the operation to reduce distant metastases after radical excision (Chau et al. 2003).

Neoadjuvant therapy for middle and lower rectal cancer (the inferior border of the tumor is less than 12 cm away from the anal border).

Combined radiochemotherapy or radiotherapy is recommended for patients with a primary rectal cancer of T3 or above or any T stage with N(+), without complications of hemorrhage, obstruction or perforation (Cervantes et al. 2008).

Liver and tumor regional arterial infusion therapy

Patients diagnosed with stage III cancers without symptoms of hemorrhage, obstruction or perforation are recommended to undergo neoadjuvant treatment using 5-FU (or its precursor) combined with oxaliplatin-infused via liver artery and tumor regional artery, respectively. Radical excision is performed 7–10 days after chemotherapy. At present, preliminary results found this treatment plan may help prevent liver metastases (Xu et al. 2007), and it can be monitored in clinical research, and not recommended as a routine.

-

2.

Neoadjuvant therapy for colon cancer.

There is no clear evidence that patients with colon cancer benefit from neoadjuvant therapy. Liver and tumor regional arterial infusion therapy will help reduce metachronous liver metastases in patients with stage III colon cancer, while not recommended as a routine.

Portal vein chemotherapy and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for colorectal cancer patients without metastasis

Encouraging data have shown that this treatment plan combined with adjuvant chemotherapy can reduce the occurrence of liver metastases (Chang et al. 2016). This treatment plan is not recommended as a routine.

Adjuvant treatment after radical excision of colorectal cancer without metastasis

-

Stage III colon cancer patients should be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for 3–6 months after surgical treatment. Optional treatment regimens include FOLFOX, CapeOX, 5-FU/LV or monotherapy with capecitabine (Andre et al. 2009).

Stage II patients with a high risk of disease recurrence [T4; poor histo-differentiation (except in MSI-H colorectal cancer); lymphatic invasion around the tumor; intestinal obstruction; or T3 with local perforation or blockage, an uncertain or positive resection margin or fewer than 12 lymph nodes biopsied] should be treated with chemotherapy using the same treatment plan described for stage III patients (Wolpin and Mayer 2008). Stage II patients without high risk factors are recommended to undergo clinical observation and follow-up visits or monotherapy with fluorouracil (except in microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) colorectal cancer).

Rectal cancer patients with T3 or above or any T stage with N(+) who have not received radiotherapy and chemotherapy before surgery are recommended to undergo adjuvant radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy after surgery. It is necessary for patients who have received radiotherapy or combined radiochemotherapy before surgery to receive adjuvant therapy.

Role of the MDT in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal liver metastases

As the most effective treatment mode for oncologic disease, an MDT is recommended for patients with colorectal liver metastases (Nordlinger et al. 2010). The MDT evaluates patients according to their physical status, age, organ function and comorbidities, and provides the most reasonable examination and the most appropriate comprehensive treatment plans for different treatment goals.

For less fit patients who cannot tolerate intense treatment, monotherapy (or combined with targeted therapy), a reduced dose of 5-FU/LV or optimal supportive care is recommended to improve quality of life and prolong survival. If the patient’s general condition improves, intense treatment can be provided.

-

For patients who can tolerate intense chemotherapy, different treatment goals and a personalized treatment plan should be based on the specific conditions of the liver metastases and the presence of extrahepatic metastases.

- The primary goal is clearly curative when R0 resection can be initially achieved for liver metastases with favorable oncological behaviors or technical criteria. Corresponding neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant therapy should be provided around surgical treatment to reduce the risk of recurrence after surgery. Whether R0 resection of liver metastases can be achieved should be jointly determined by experts in liver surgery, tumor surgery, and imaging. If liver metastases can be removed by R0 resection but the surgery is technically difficult, other means of partial destruction (radiofrequency ablation or/and stereotactic radiotherapy) should be actively used to achieve NED.

- For patients with initially unresectable liver metastases, conversion therapy is recommended to render initially unresectable colorectal metastases resectable and to achieve NED. Patients in generally good condition can tolerate local treatment, including liver metastases surgery, and intense treatment. The primary goal for these patients is to minimize the size of the metastases or to increase the volume of the residual liver, and the most active comprehensive treatment should be used.

- For patients who can tolerate intense treatment but will never be candidates for liver metastases resection or reach NED, the primary goal is disease control since they require a rapid reduction of tumor burden. Active combined therapy should be used.

Surgery and other local ablative treatments (LATs) for colorectal liver metastases

Surgical treatment

Complete surgical resection of metastatic lesions is still the optimal approach to cure colorectal liver metastases (Hur et al. 2009). Thus, for patients with colorectal liver metastases, the treatment strategy should be directed towards complete resection whenever possible. A proportion of patients with initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases should be considered for secondary resection if they become resectable upon conversion therapy.

Indications and contraindications for surgical treatment of liver metastases

Indications:

The primary colorectal cancer can be or was already completely removed (R0).

Based on liver anatomy and the extent of liver metastases, the metastatic lesions can be completely removed (R0) while preserving adequate liver function [remnant liver volume ≥ 30–40%; three-dimensional CT and digital imaging technology will help to evaluate the liver volume (Begin et al. 2014)].

Patients should be fit to undergo such surgical treatment, without extrahepatic metastases that are not suitable for surgery or LATs, or with only pulmonary nodules that do not restrict the resectability of the liver metastases.

In addition, patients with an estimated specimen resection margin of less than 1 cm, portal lymph node metastasis, or extrahepatic metastases (i.e., lung, peritoneum) can also be considered candidates for surgical treatment with curative intent.

Contraindications:

Radical resection (R0) of the primary tumor cannot be performed.

Extrahepatic metastases cannot be resected surgically.

The predicted volume of the remnant liver after surgery is inadequate.

The patient is intolerant to the planned surgical treatment.

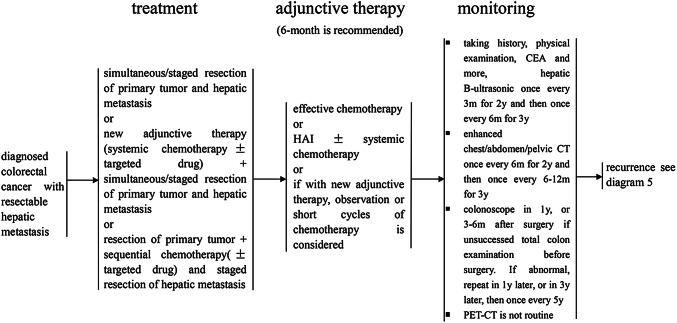

Surgical treatment for patients with liver metastases at the time of colorectal cancer diagnosis (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Treatment of diagnosed colorectal cancer with resectable hepatic metastasis

Synchronous resection of the primary tumor and liver metastases

For patients with liver metastases that are small and located either peripherally or confined to one lobe of the liver, when the planned volume of hepatectomy is < 50% or suspicious portal lymph nodes, intra-abdominal or other distant metastases can be completely resected, then synchronous resection of both the primary tumor and metastases is recommended. Some studies have reported higher operative mortality and more complications following such synchronous resections compared with staged resections (Roxburgh et al. 2012). Therefore, the decision to perform synchronous resection should be made with caution, especially when two incisions are needed.

In emergencies, synchronous resection of the primary tumor and liver metastases is not recommended due to incomplete preoperative examinations and a greater possibility of infection (Weber et al. 2003).

Staged resection of the primary tumor and liver metastases

For patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases that are not suitable for synchronous resection, staged resection is recommended. And resection of the primary tumor is performed first followed by the resection of liver metastases, usually 4–6 weeks later. If neoadjuvant therapy is considered, the resection of liver metastases can be postponed for up to 3 months after resection of the primary tumor. For patients with recurrent colorectal cancer with resectable liver metastases, the treatment strategy is similar, but staged resection is preferred.

In addition, the liver first approach to the resection of liver metastases followed by resection of the primary tumor is also applied. The reported incidence of complications, mortality and 5-year survival rate are comparable to the conventional staged resection.

Surgical treatment for patients who develop liver metastases after radical resection of colorectal cancer

For patients whose primary tumors have been radically resected without local recurrence, radical resection of liver metastases can be considered when the liver volume of the planned hepatectomy is less than 70% (without liver cirrhosis), and neoadjuvant therapy is optional (Tomlinson et al. 2007).

The diagnosis of liver metastases after radical excision of colorectal cancer should be supported by at least two kinds of imaging examinations, including B-ultrasonography, enhanced CT and enhanced MRI. PET–CT can help to indicate the extent of the liver metastases and the presence of extrahepatic metastases to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Surgical approaches to liver metastases

After hepatectomy, at least one of three liver veins is preserved, and the remnant volume is more than 40% for synchronous resection and 30% for staged resection. Hepatectomy should be R0 resection, and the resection margin is at least 1 mm.

For large liver metastases confined to one lobe of the liver (without liver cirrhosis), anatomic hemi-hepatectomy is optional.

Intraoperative ultrasonography is recommended. This procedure can help identify liver metastases that are not detected by preoperative examinations.

Portal vein embolization (PVE) or portal vein ligation (PVL) can result in compensatory enlargement of the remnant liver, which will increase the possibility of liver surgery.

Associating liver partition and PVL for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) (Torres et al. 2012) can significantly increase the volume of the residual liver in a relatively short period of time and provide more opportunities for phase II hepatectomy (Bertens et al. 2015). However, the operation is complicated, and the associated complications and mortality are higher than in traditional liver resection. Therefore, it is recommended that this surgical procedure be performed by experienced liver surgeons in strictly selected patients (Ratti et al. 2015).

Surgical treatment for recurrent colorectal liver metastases and extrahepatic metastases

Under conditions that patients remain tolerant to surgery and the remnant liver volume is sufficient, recurrent liver metastases that remain resectable can receive a second and even a third hepatectomy. Studies have indicated that the incidence of complications, mortality and the survival rate of repeat hepatectomy are similar to those of the first hepatectomy (Antoniou et al. 2007).

Similarly, under conditions of good tolerance to surgery, patients with resectable extrahepatic metastases (i.e., lung, peritoneum) can undergo staged or synchronous resection of these metastases.

LATs that can achieve NED

Apart from surgical resection of liver metastases, some local treatments, including radiofrequency ablation and radiotherapy, can also eradicate metastatic lesions. Thus, for patients with individual lesions that are difficult to resect surgically, these LATs should be considered to provide more patients with the possibility of achieving NED and to improve survival.

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for patients with colorectal liver metastases that can achieve NED

Neoadjuvant therapy

Neoadjuvant therapy for patients with liver metastases at the time of colorectal cancer diagnosis

Under conditions in which the primary tumor is not complicated by hemorrhage, obstruction or perforation at the time of diagnosis, neoadjuvant therapy is optional, except for patients with liver metastases that are technically easy to remove and without poor prognostic indicators [such as a clinical risk score (CRS) < 3] (Poultsides et al. 2009). For those with large or numerous liver metastases or suspicious lymph node metastases of the primary tumor, neoadjuvant therapy is recommended.

Systematic regimens for neoadjuvant therapy include FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, CapeOX, and FOLFOXIRI. The addition of targeted therapy remains controversial (Folprecht et al. 2010; Primrose et al. 2014). Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy can be used in combination with systematic regimens (Kemeny et al. 2005).

To reduce the adverse effects of chemotherapy during liver surgery, neoadjuvant therapy should consist of no more than six cycles. Generally, neoadjuvant therapy is completed in 2–3 months and followed by liver surgery.

Neoadjuvant therapy for patients who develop liver metastases after radical resection of colorectal cancer

It is recommended that after radical resection of the primary tumor, patients without adjuvant chemotherapy or with exposure to chemotherapy more than 12 months preceding the discovery of liver metastases receive neoadjuvant therapy as the above. For patients with exposure to chemotherapy in the 12 months prior to the discovery of liver metastases, surgical resection of liver metastases together with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended. The addition of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy can be considered.

Adjuvant therapy after resection of liver metastases

All patients who undergo radical resection of liver metastases should receive adjuvant chemotherapy. It is recommended that the total duration of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy be no longer than 6 months. Neoadjuvant therapeutic regimens that have been shown to be effective should be the first choice for adjuvant therapy in the absence of contraindications.

Combination therapy for colorectal liver metastases in patients who cannot achieve NED

Selection of the treatment strategy

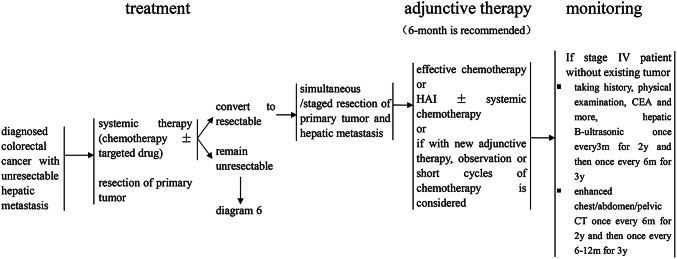

Diagnosis of colorectal cancer with liver metastasis without achieving NED (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Treatment of diagnosed colorectal cancer with unresectable hepatic metastasis

For patients with unresectable liver metastases and colorectal cancer-related emergencies (hemorrhage, obstruction or colonic perforation), surgical removal of the primary colorectal cancer should be performed as an urgent matter followed by the administration of systemic chemotherapy [or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (Mahnken et al. 2013)], and targeted therapy may be combined with such therapy (Van Cutsem et al. 2009). After every 6–8 weeks of treatment, the liver should be reexamined using B-ultrasonography, CT and/or MRI to evaluate the efficacy of treatment (Pawlik et al. 2007). If the liver metastases become resectable or make NED possible, then liver surgery or liver surgery combined with LATs should be offered; however, if the liver metastases preclude NED, combination therapy should be continued (Fraker and Soulen 2002).

If the first presentation of colorectal cancer is not complicated by hemorrhage, obstruction or perforation, systemic chemotherapy (or the addition of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy) is recommended, and targeted therapy can be combined with the initial treatment. If unresectable liver metastases become resectable or make NED achievable, liver resection or liver surgery combined with LATs should be considered. If the liver metastases preclude NED, the primary tumor could be resected according to the situation, and combination therapy should be continued after surgery.

Such patients can also choose to first undergo primary colorectal surgery and then undergo further treatment as described above. However, it remains controversial whether the primary lesions should be resected when they do not cause bleeding, obstructive symptoms, or perforation in patients with combined liver metastases that cannot achieve NED.

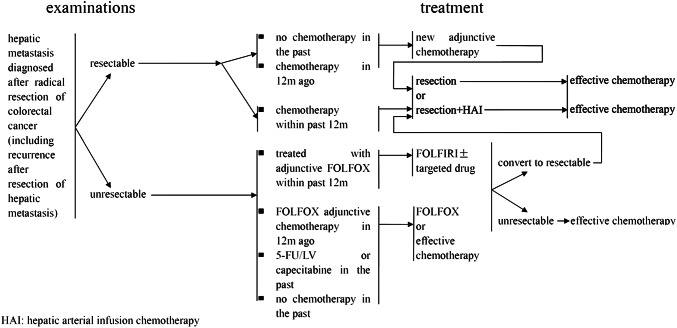

Patients with liver metastases that cannot achieve NED after colorectal surgery (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

Treatment for hepatic metastasis diagnosed after radical excision of colorectal cancer

The regimens of 5-FU/LV or capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin or irinotecan offer the best opportunities for patients with unresectable liver metastases are recommended as first-line treatment, and the addition of targeted therapy or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy is optional.

For patients who have undergone oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in the previous 12 months before liver metastases, we should switch to FOLFIRI. While those who develop liver metastases after 12 months of chemotherapy finish, FOLFOX or CapeOX can also be used, and the addition of targeted therapy, or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy is optional.

After every 6–8 weeks of treatment, the liver should be reevaluated using B-ultrasonography, CT and/or MRI to evaluate the efficacy of treatment. If liver metastases become resectable or achieve NED, liver surgery and other local ablative measures should be performed, and adjuvant chemotherapy should be offered; however, if NED cannot be achieved, combination therapy should be continued.

Methods of treatment

Systemic chemotherapy and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Chemotherapy for unresectable hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer

-

Initial chemotherapy.

- Conversion therapy is essential for patients with liver metastases and the potential to achieve NED.

Chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFOX, FOLFIRI or CapeOX can increase conversion rate, as the first-line regimen. Chemotherapy combined with targeted drugs can further increase conversion (Van Cutsem et al. 2015). Current data show that chemotherapy combined with bevacizumab provides good disease control and conversion rates (Okines et al. 2009), while RAS wild-type patients can also be treated with chemotherapy and cetuximab.

Fit patients who can tolerate more powerful chemotherapy can be considered for FOLFOXIRI (Falcone et al. 2007). However, there are many adverse reactions that need to be paid attention to. Currently, the program has a good clinical data in combination with bevacizumab, which can be applied cautiously in selective patients.

-

(b)

Patients with liver metastases who cannot achieve NED. FOLFOX, FOLFIRI and CapeOX regimens, or a combination with appropriate targeted therapy, is recommended. Although FOLFOXIRI has a high response rate, it is also toxic, and whether it should be used in such patients is not clear.

-

2.

Maintenance therapy or suspension of chemotherapy.

For patients who achieved remission or stabilization after the induction of chemotherapy but have persistent liver metastasis that cannot eliminated by R0, the 5-FU/LV and capecitabine regimens or combined with bevacizumab are recommended to reduce the toxicity of continuous high-intensity chemotherapy. Chemotherapy can also be suspended(Esin and Yalcin 2016).

-

3.

Chemotherapeutic options when disease progresses.

- When FOLFOX (or CapeOX) ± targeted therapy regimens are used as first-line therapy, FOLFIRI [or mXELIRI (Xu et al. 2018)] can be considered if disease progresses. When disease progresses as FOLFIRI ± targeted therapy being the first-line therapy, FOLFOX (or CapeOX) ± targeted therapy regimens can be under consideration. If the disease continues to progress while receiving the second-line chemotherapy, regorafenib (Grothey et al. 2013) or fruquintinib (Li et al. 2018) or cetuximab (Iwamoto et al. 2014) (never used before, RAS wild-type only, ± irinotecan) or best supportive care (Chau et al. 2003) can be taken into consideration.

- If the disease progresses while receiving 5-FU/LV with targeted therapy, then the FOLFOX, FOLFIRI and CapeOX regimens or combination with targeted therapy is recommended. If the condition again progresses, regorafenib or fruquintinib or best supportive care is recommended (Hurwitz et al. 2004).

-

4.

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy or transcatheter arterial chemoembolization can be combined with and administered during the above treatments at the appropriate time, to prolong overall survival. In particular, hepatic arterial infusion of drug-eluting beads can further improve efficacy (Nosher et al. 2015). However, this monotherapy is not superior to systemic chemotherapy.

LATs

For patients with liver metastases that cannot be surgically removed, appropriate treatments to strengthen local control should be selected based on systemic chemotherapy, determined by the MDT, taking into account the patient’s wishes.

-

Ablation treatment.

- Radiofrequency ablation.

Radiofrequency ablation is used only after chemotherapy failure or for the treatment of recurrences of liver metastases (Brouquet et al. 2011; Kawaguchi et al. 2014). It is recommended to treat liver metastases with a maximum diameter less than 3 cm, and 5 liver metastases at most can be ablated during one treatment session. For patients with too small expected residual volume, some larger liver metastases can be removed, and radiofrequency ablation can be performed for residual metastatic lesions with a diameter of less than 3 cm. Radiofrequency ablation can also be considered for patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases who are not suitable for or are unwilling to undergo surgery.

-

(b)

Microwave ablation and cryotherapy.

Compared with chemotherapy alone, a combination with microwave ablation or cryotherapy can improve survival in selected patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases, while we are cautious about complications.

-

2.

Radiotherapy.

Because the tolerated dose of radiotherapy for the whole liver is far lower than the lethal dose for the tumor, routine radiotherapy can be used only as palliative treatment. Hyperfractionation or limitation of the irradiated volume of liver should be adopted, while the local dose aimed at the liver metastases can be increased to 60–70 Gy, with high local control rate (Mohiuddin et al. 1996; Rusthoven et al. 2009; Timmerman et al. 2009). The available technologies include 3-D CRT, SBRT and IMRT, which can increase the precision of radiation therapy and reduce side effects in normal tissue (Topkan et al. 2008).

Other methods

Additional methods include intratumoral injection of absolute alcohol, and traditional Chinese medicine. The efficacy of these treatments as part of combination therapy is not superior to the above therapies. The application of any of these treatments alone will reduce the therapeutic efficacy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The members of China CRLM Guideline Group are Yi Ba, Jianhong Bu, Jianhui Cai, Sanjun Cai, Shan Zeng, Zhaochong Zeng, Gong Chen, Yu Chen, Zihua Chen, Zongyou Chen, Jiemin Cheng, Pan Chi, Guanghai Dai, Yong Dai, Yanhong Deng, Kefeng Ding, Xuedong Fang, Chuangang Fu, Jianping Gong, Chunyi Hao, Yulong He, Zhongcheng Huang, Jiafu Ji, Baoqing Jia, Kewei Jiang, Jing Jin, Dalu Kong, Ping Lan, Dechuan Li, Guoli Li, Jin Li, Leping Li, Yunfeng Li, Zhixia Li, Houjie Liang, Xiaobo Liang, Feng Lin, Jianjiang Lin, Hongjun Liu, Tianshu Liu, Yunpeng Liu, Hongming Pan, Zhizhong Pan, Haiping Pei, Tao Peng, Li Ren, Lin Shen, Chun Song, Tianqiang Song, Xiangqian Su, Yihong Sun, Min Tao, Liguo Tian, Desen Wan, Jianping Wang, Guiying Wang, Guiyu Wang, Haijiang Wang, Jianhua Wang, Lei Wang, Xin Wang, Yajie Wang, Yi Wang, Ziqiang Wang, Ye Wei, Dong Wei, Feng Xia, Jianguo Xia, Lijian Xia, Baocai Xing, Bin Xiong, Jianming Xu, Nong Xu, Ruihua Xu, Ye Xu, Zekuan Xu, Zhongfa Xu, Shujun Yang, Hongwei Yao, Yingjiang Ye, Peiwu Yu, Ying Yuan, Jun Zhang, Keliang Zhang, Wei Zhang, Xiaotian Zhang, Yanqiao Zhang, Youcheng Zhang, Zhen Zhang, Qingchuan Zhao, Ren Zhao, Shu Zheng, Aiping Zhou, Jian Zhou, Zongguang Zhou.

Funding

None.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

The members of China CRLM Guideline Group are listed to Acknowledgements section.

Contributor Information

Jianmin Xu, Email: xujmin@aliyun.com.

China CRLM Guideline Group:

Yi Ba, Jianhong Bu, Jianhui Cai, Sanjun Cai, Shan Zeng, Zhaochong Zeng, Gong Chen, Yu Chen, Zihua Chen, Zongyou Chen, Jiemin Cheng, Pan Chi, Guanghai Dai, Yong Dai, Yanhong Deng, Kefeng Ding, Xuedong Fang, Chuangang Fu, Jianping Gong, Chunyi Hao, Yulong He, Zhongcheng Huang, Jiafu Ji, Baoqing Jia, Kewei Jiang, Jing Jin, Dalu Kong, Ping Lan, Dechuan Li, Guoli Li, Jin Li, Leping Li, Yunfeng Li, Zhixia Li, Houjie Liang, Xiaobo Liang, Feng Lin, Jianjiang Lin, Hongjun Liu, Tianshu Liu, Yunpeng Liu, Hongming Pan, Zhizhong Pan, Haiping Pei, Tao Peng, Li Ren, Lin Shen, Chun Song, Tianqiang Song, Xiangqian Su, Yihong Sun, Min Tao, Liguo Tian, Desen Wan, Jianping Wang, Guiying Wang, Guiyu Wang, Haijiang Wang, Jianhua Wang, Lei Wang, Xin Wang, Yajie Wang, Yi Wang, Ziqiang Wang, Ye Wei, Dong Wei, Feng Xia, Jianguo Xia, Lijian Xia, Baocai Xing, Bin Xiong, Jianming Xu, Nong Xu, Ruihua Xu, Ye Xu, Zekuan Xu, Zhongfa Xu, Shujun Yang, Hongwei Yao, Yingjiang Ye, Peiwu Yu, Ying Yuan, Jun Zhang, Keliang Zhang, Wei Zhang, Xiaotian Zhang, Yanqiao Zhang, Youcheng Zhang, Zhen Zhang, Qingchuan Zhao, Ren Zhao, Shu Zheng, Aiping Zhou, Jian Zhou, and Zongguang Zhou

References

- Adam R et al (2015) Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer Treatm Rev 41:729–741. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre T et al (2009) Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 27:3109–3116. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou A et al (2007) Meta-analysis of clinical outcome after first and second liver resection for colorectal metastases. Surgery 141:9–18. 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begin A et al (2014) Accuracy of preoperative automatic measurement of the liver volume by CT-scan combined to a 3D virtual surgical planning software (3DVSP). Surg Endosc 28:3408–3412. 10.1007/s00464-014-3611-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertens KA, Hawel J, Lung K, Buac S, Pineda-Solis K, Hernandez-Alejandro R (2015) ALPPS: challenging the concept of unresectability—a systematic review. Int J Surg 13:280–287. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouquet A, Andreou A, Vauthey JN (2011) The management of solitary colorectal liver metastases. Surgeon 9:265–272. 10.1016/j.surge.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes A, Rosello S, Rodriguez-Braun E, Navarro S, Campos S, Hernandez A, Garcia-Granero E (2008) Progress in the multidisciplinary treatment of gastrointestinal cancer and the impact on clinical practice: perioperative management of rectal cancer. Ann Oncol 19(Suppl 7):vii266–vii272. 10.1093/annonc/mdn438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W et al (2016) Randomized controlled trial of intraportal chemotherapy combined with adjuvant chemotherapy (mFOLFOX6) for stage II and III colon cancer. Ann Surg 263:434–439. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau I, Chan S, Cunningham D (2003) Overview of preoperative and postoperative therapy for colorectal cancer: the European and United States perspectives. Clin Colorectal Cancer 3:19–33. 10.3816/CCC.2003.n.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenegrachts K, De Geeter F, ter Beek L, Walgraeve N, Bipat S, Stoker J, Rigauts H (2009) Comparison of MRI (including SS SE-EPI and SPIO-enhanced MRI) and FDG-PET/CT for the detection of colorectal liver metastases. Eur Radiol 19:370–379. 10.1007/s00330-008-1163-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MC et al (2009) Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg 250:440–448. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4539b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbeke D, Martin WH (2004) PET and PET–CT for evaluation of colorectal carcinoma. Semin Nucl Med 34:209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esin E, Yalcin S (2016) Maintenance strategy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 42:82–90. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone A et al (2007) Phase III trial of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) compared with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. J Clin Oncol 25:1670–1676. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folprecht G et al (2010) Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 11:38–47. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JH (1984) Treatment of metastatic disease of the liver: a skeptic’s view. Semin Liver Dis 4:170–179. 10.1055/s-2008-1040656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker DL, Soulen M (2002) Regional therapy of hepatic metastases. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am 16:947–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothey A et al (2013) Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 381:303–312. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur H et al (2009) Comparative study of resection and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of solitary colorectal liver metastases. Am J Surg 197:728–736. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H et al (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2335–2342. 10.1056/NEJMoa032691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto S et al (2014) Multicenter phase II study of second-line cetuximab plus folinic acid/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan (FOLFIRI) in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: the FLIER study. Anticancer Res 34:1967–1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones OM, Rees M, John TG, Bygrave S, Plant G (2005) Biopsy of resectable colorectal liver metastases causes tumour dissemination and adversely affects survival after liver resection. Br J Surg 92:1165–1168. 10.1002/bjs.4888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y et al (2014) Surgical resection for local recurrence after radiofrequency ablation for colorectal liver metastasis is more extensive than primary resection. Scand J Gastroenterol 49:569–575. 10.3109/00365521.2014.893013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny N et al (2005) Phase I trial of systemic oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy with hepatic arterial infusion in patients with unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:4888–4896. 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshariya M et al (2007) An update and our experience with metastatic liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology 54:2232–2239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J et al (2018) Effect of fruquintinib vs placebo on overall survival in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: the FRESCO randomized clinical trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 319:2486–2496. 10.1001/jama.2018.7855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnken AH, Pereira PL, de Baere T (2013) Interventional oncologic approaches to liver. metastases. Radiology 266:407–430. 10.1148/radiol.12112544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin M, Chen E, Ahmad N (1996) Combined liver radiation and chemotherapy for palliation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 14:722–728. 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlinger B, Vauthey JN, Poston G, Benoist S, Rougier P, Van Cutsem E (2010) The timing of chemotherapy and surgery for the treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Clin Colorectal Cancer 9:212–218. 10.3816/CCC.2010.n.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosher JL, Ahmed I, Patel AN, Gendel V, Murillo PG, Moss R, Jabbour SK (2015) Non-operative therapies for colorectal liver metastases. J Gastrointest Oncol 6:224–240. 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okines A, Puerto OD, Cunningham D, Chau I, Van Cutsem E, Saltz L, Cassidy J (2009) Surgery with curative-intent in patients treated with first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer First BEAT and the randomised phase-III NO16966 trial. Br J Cancer 101:1033–1038. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno K (2007) Surgical treatment for digestive cancer. Current issues—colon cancer. Dig Surg 24:108–114. 10.1159/000101897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlik TM, Olino K, Gleisner AL, Torbenson M, Schulick R, Choti MA (2007) Preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: impact on hepatic histology and postoperative outcome. J Gastrointest Surg 11:860–868. 10.1007/s11605-007-0149-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poultsides GA et al (2009) Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without surgery as initial treatment. J Clin Oncol 27:3379–3384. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primrose J et al (2014) Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis: the New EPOC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:601–611. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70105-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratti F et al (2015) Strategies to increase the resectability of patients with colorectal liver metastases: a multi-center case-match analysis of ALPPS and conventional two-stage hepatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 22:1933–1942. 10.1245/s10434-014-4291-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex DK et al (2006) Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after cancer resection: a consensus update by the American Cancer Society and US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer CA: a cancer. J Clin 56:160–167 (quiz 185–166) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh CS, Richards CH, Moug SJ, Foulis AK, McMillan DC, Horgan PG (2012) Determinants of short- and long-term outcome in patients undergoing simultaneous resection of colorectal cancer and synchronous colorectal liver metastases. Int J Colorectal Dis 27:363–369. 10.1007/s00384-011-1339-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusthoven KE et al (2009) Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 27:1572–1578. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman RD, Bizekis CS, Pass HI, Fong Y, Dupuy DE, Dawson LA, Lu D (2009) Local surgical, ablative, and radiation treatment of metastases CA: a cancer. J Clin 59:145–170. 10.3322/caac.20013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson JS et al (2007) Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol 25:4575–4580. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topkan E, Onal HC, Yavuz MN (2008) Managing liver metastases with conformal radiation therapy. J Support Oncol 6:9–13, 15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres OJ, Moraes-Junior JM, Lima e Lima NC, Moraes AM (2012) Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): a new approach in liver resections. Braz Arch Dig Surg 25:290–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E et al (2009) Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 360:1408–1417. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E et al (2015) Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 33:692–700. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JC, Bachellier P, Oussoultzoglou E, Jaeck D (2003) Simultaneous resection of colorectal primary tumour and synchronous liver metastases. Br J Surg 90:956–962. 10.1002/bjs.4132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpin BM, Mayer RJ (2008) Systemic treatment of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 134:1296–1310. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J et al (2007) Preoperative hepatic and regional arterial chemotherapy in the prevention of liver metastasis after colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 245:583–590. 10.1097/01.sla.0000250453.34507.d3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RH et al (2018) Modified XELIRI (capecitabine plus irinotecan) versus FOLFIRI (leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan), both either with or without bevacizumab, as second-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer (AXEPT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 19:660–671. 10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30140-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.