Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) plays a key role in leukocytic and non-leukocytic cells. Germ line mutations in STAT3, which are mainly found in the SH2, DNA binding and transactivation domains, can be loss- or gain-of-function (LOF and GOF). STAT3 N-terminal domain (NTD) mutations are rare, and their biological effects remain incompletely understood. We explored the significance of STAT3 NTD p.Trp37* variant in a patient with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and a low Hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES) score. In cell culture models, the expression of full-length p.Trp37* allele showed shorter STAT3 protein expression suggesting a re-initiation (Met99 or Met143). STAT3 activity using luciferase reporter assay showed a twofold-increased activity of the STAT3 p.Trp37* STAT3 protein compared with WT STAT3 at basal level and upon IL-6 stimulation. In contrast, the activity of the short pTrp37* peptide (amino acids 1 to 37) was amorphic but without dominant negative (DN) effect on transcriptional activity or STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation. The proteins initiated at Met99 and Met143 were surprisingly hypermorphic. In carriers’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), both WT and mutated STAT3 mRNA were equally present and the global amount of STAT3 protein was not significantly reduced. In stimulated heterozygous carriers’ PBMCs, however, STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation and Th17 were reduced but not completely abolished. This suggests a DN effect of an unknown product of the p.Trp37* allele. Transcriptomics analysis of PBMCs from the index revealed selectively distinct gene expression. We conclude that heterozygosity for the NTD p.Trp37* STAT3 mutation defines a novel allelic form of STAT3 deficiency, associated with a chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and minor signs of HIES.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10875-025-01867-1.

Keywords: STAT3, Pulmonary aspergillosis, Mutation

Introduction

Dominant negative (DN) loss-of-function (LOF) mutations in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) gene cause hyper IgE syndrome (HIES) [1, 2]. Clinical HIES diagnosis is based on scoring of pneumonia susceptibility, newborn rash, pathological bone fractures, characteristic facies, and high-arched palate [3–5]. STAT3 gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in turn lead to early-onset autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation [6, 7]. In addition to LOF and GOF, germline “multimorphic” pathologic variants with variable clinical and biological findings and mixed GOF, LOF, and neomorphic effects have recently been reported, also in STAT3 [5, 8, 9]. Heterozygous non-sense STAT3 mutations causing nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the affected mRNA have also been described [10, 11] but were not fully investigated in vivo although they have been shown to be dominant by DN effect in vitro [2].

Most autosomal DN STAT3 LOF pathogenic variants are found in the SH2, DNA binding and transactivation domains [2, 4]. In contrast, a low number of pathogenic germline DN N-terminal domain (NTD) STAT3 variants has been reported. This NTD contain the N-terminal part and the coiled-coil domain and has been involved in the nuclear translocation, and dimerization of STAT3 [7, 12, 13].

We report here the clinical, genetic, and immunological features of a previously healthy young female who presented with an acute onset of bloody sputum caused by chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) and carried a private STAT3 variant in the NTD of unknown significance.

Methods

Genetic Analysis

Exome and targeted Sanger sequencing were completed as previously described in [14]. Whole genome sequencing was performed on Illumina® NovaSeq6000 at the Oslo University Hospital using DNA extracted from whole blood after library prep with Illumina® DNA Prep. DRAGEN 4.1-GATK with reference-genome GRCh38 was used for alignment, annotating and variant calling. An in-house curated gene panel containing 862 validated inborn errors immunity (IEI) genes were used for in silico filtering of variants. Splice variants were bioinformatically filtered based on SpliceAI-score [15], and manually checked with prediction tools in Alamut™ Visual Plus.

Flow Cytometry

For the analysis of intracellular pSTAT3 and pSTAT1, PBMCs were isolated with Ficoll-Plaque gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare Biosciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Isolated PBMC were stored in RPMI-10% FBS-10% DMSO at −140˚C. The cells were thawed, let to rest overnight at 37 ˚C in a cell incubator, washed and stained for 30 min at room temperature with anti-CD4 antibody (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA). After staining the cells were washed twice with supplemented RPMI-2% FBS medium, resuspended (2–5 × 106 cells /mL), and incubated for 30 min at 37 ˚C before the stimulants were added. After 0, 7.5, 15, 30 or 45 min of stimulation with IL-6 (50 ng/mL), IL-21 (10 ng/mL), IL-27 (200 ng/mL) (Peprotech, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) or IFN-α (10,000U/mL) (Gibco, Waltham, USA) at 37 ˚C, the incubation was stopped with an equal volume of prewarmed 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37˚C. After two washes with PBS-2% FBS, chilled Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) was added on the cells and incubated for 30 min on ice. The samples were washed twice with PBS-2% FBS and stained for pSTAT3 and pSTAT1 with BD Phosflow™ antibodies (BD Biosciences) for 35 min on ice. After washing the cells were acquired using an LSR Fortessa (BD) flow cytometer, and data were analysed using FlowJo software (V10, Tree Star).

For the analysis of total STAT3, the PBMC were thawed and plated in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were stimulated with IL-6 (50 ng/ml) for 30 min. To detect STAT3, the cells were permeabilized and fixed for 40 min at 4 °C using the Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The cells were washed twice with permeabilization buffer and stained for STAT3 (BioLegend) for 40 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed, acquired, and analysed as before.

Exon-Trapping Assay

The exon-trapping assay was performed as previously described [2, 16, 17]. STAT3 gDNA was amplified from control fibroblasts. The pair of primers was designed to amplify the genomic region between 200 upstream the exon 2 (5’-cttgagtccaggagttcaaggccac) and 200 nucleotides downstream exon 4 (5’-ccattgggtctgttggattcttttggtg) of STAT3. Genomic STAT3 amplified sequence was inserted into the pSPL3 plasmid (Life Technologies). The variant was reintroduced by directed mutagenesis, and the full STAT3 gDNA fragment was Sanger sequenced. Plasmids were used to transfect Cos-7 cells with the X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection, and total RNA was extracted as previously described. After cDNA synthesis, PCR was performed with the SD6 (5′-TCTCAGTCACTGGACAACC-3′) and SA2 (5′-ATCTCAGTGGTATTTGTGAGC-3′) primers for pSPL3 plasmids. The amplified cDNAs were inserted into the pCR4-TOPO plasmid vector (Invitrogen). M13 forward (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAG-3′) and M13 reverse (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′) primers were used for amplifications for the analysis of potential splicing. We screened 100 colonies for each variant to analyze splicing.

NanoString Analysis of Patient PBMCs

NanoString direct mRNA counting was performed with a custom code set as described previously [18]. The list of NanoString targets is in Supplemental Table 2.

RNA-sequencing

PBMCs from cases and controls were stimulated with IL-6 (30 ng/mL) for 30 min for RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq). Total RNA was isolated with RNeasy Isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA-seq libraries preparation and sequencing were performed by BGI Tech Solutions (Hongkong) using the DNBseq platform. Data analysis was performed by BGI Tech Solutions. After filtering and cleaning, the sequencing reads were mapped to a reference genome (hg19_UCSC_20180822) using the HISAT/Bowtie2 tool. Gene expression level was calculated by RNA-seq by Expectation Maximization (RSEM). Differentially expressed genes were screened using PossionDis which is based on the poisson distribution, performed as described at Audic S, et al. [19]. The KEGG database was used to perform pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs between the indexed patient and her control.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was purified from IL-6-stimulated PBMCs isolated from cases and control samples with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen) was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and PROBE FAST ABI Prism 2X qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems) for the TaqMan Master Mix. Primers for human FOXP3, RORC and TBX21 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and ThermoFisher Scientific. Gene-specific primers and probes were designed from the Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche Applied Science), and Universal Probe Library probes and custom ordered oligonucleotides are shown in Supplemental Table 3. The relative quantification of gene expression was carried out with Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System. Relative gene expression was calculated using the endogenous control gene EF1alpha to normalise the target gene.

Luciferase assay

Luciferase assay as performed was previously described [2].

Transfection of STAT3 p.Tyr37*

STAT3 p.Tyr37* was constructed to MAC-tag-N vector [20] and was transfected to HEK293 cells using calcium phosphate. Two days after transfection, cells were stimulated with or without IL-6 (30 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for 30 min. Cells were collected for further Western blot detections of tyrosine phosphorylated STAT3 and total STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, USA).

Results

Case Description

The index case with mild asthma (patient II:5) had not suffered from infections or features of HIES (NIH HIES score 16, STAT3 score 0) until she developed flu-like symptoms and hemoptysis at age 22. C-reactive protein (CRP) level and sedimentation rate were low. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a cavity with a rounded mass in the left lung upper lobe (Fig. 1A-B). Bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum samples were positive for Aspergillus fumigatus and negative for other pathogens. Her immunological evaluations were unremarkable although her serum IgE (380–514 IU/L, normal range < 110 IU/L) and serum Aspergillus specific IgE (2.03 IU/L; normal < 0.35 IU/L) were somewhat elevated. The cavitating lung lesion was surgically removed. The necrotic tissue samples were positive for Aspergillus fumigatus (Fig. 1C-E) and abundant eosinophils. The patient received intravenous voriconazole (200 mg twice daily) followed by oral voriconazole for one month. She had remained asymptomatic with unremarkable chest CT for six years when she developed another episode of cough and bloody sputum. Again, CT scan revealed left upper lobe lesion suggestive of aspergillosis (Fig. 1F-G). The lesion was surgically removed (Fig. 1H). Histology was consistent with aspergillosis and severe tissue necrosis suggesting necrotizing CPA. She received voriconazole followed by oral posaconazole for one year at which point her chest CT was unremarkable (Fig. 1I). Soon after, additional multiple solid lesions were observed in her lung CT (Fig. 1J-K) leading to the need of another surgical treatment. Importantly, the patient did not develop non-infectious pneumatoceles or broncho-pleural fistulae. The patient started to receive oral isavuconazole (serum concentration 3.76 mg/L) and two-week courses of liposomal amphotericin B (Ambisome, 3 mg/kg). Intravenous immunoglobulin G (IgG) substitution was administered due to a slightly low response to the Pneumovax vaccine. Despite these medications, additional pulmonary lesions developed. Asymptomatic family members were carefully investigated, and they were given instructions to avoid mold exposures and to seek for medical attention for prolonged cough. They have access to high quality immunological and clinical care.

Fig. 1.

The index presented with bloody sputum at age 22 when her chest CT was consistent with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (A, B). Histology of the lung lesion was consistent with aspergillosis and displayed high numbers of eosinophils (C-E). Seven years later, hemoptysis recurred, and chest CT showed a new aspergillosis lesion (F, G) which was surgically removed (H). One year later, the CT scan appeared unremarkable (I). Soon after, several new aspergillosis lesions were found (J, K) leading to surgical removal of the largest lesions. Medications (vori, voriconazole; posaconazole; isavuconazole; Ambisome, liposomal amphotericin B; IgG, intravenous IgG substitution) are indicated. Blue solid arrows on the timeline indicate the surgical operations

Genetics, STAT3 p.Trp37* Variant Gene Products and STAT3 Phosphorylation

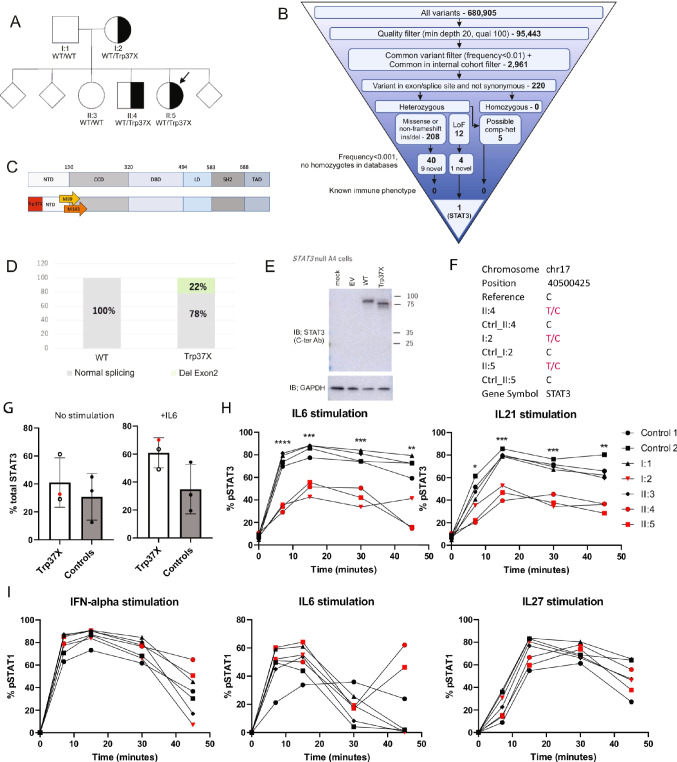

Whole exome sequencing (WES) revealed a private heterozygous premature termination variant in STAT3 gene (Chr17:40,500,425 C > T; NM-213662:exon2:c.G110A:p.Trp37*). The STAT3 variant was also found in heterozygosity in her mother (I:2) and her brother (II:4) (Fig. 2A, B and C) who were both asymptomatic, had low HIES score and no history suggestive of HIES, STAT3 GOF or any other immunodeficiency condition. No other genetic variants with potential significance from the patient’s WES have been identified (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, no other clinically significant variants were observed in an in-house curated set of known and putative IEI genes based on genome sequencing of the patient’s DNA.

Fig. 2.

A Family segregation of the STAT3 p.Trp37* allele in the kindred. The index (II:5) is marked with a solid arrow. B A schematic of the filtering criteria and amounts of variants from whole exome analysis (C). Whole exome sequencing revealed a private heterozygous premature stop gained (p.Trp37*) in STAT3 gene. Possible re-initiation sites (methionine 99 and 143) are indicated with arrows. D p.Trp37* variant affects the splicing of exon 2 in STAT3. E STAT3 immunoblotting on STAT3 deficient A4 cells transfected with WT or p.Trp37* STAT3 variant. p.Trp37* STAT3 variant produced lower MW products compared to WT STAT3, indicating a re-initiation. F The STAT3 p.W37X mutation expression from RNA-Seq data. G Intracellular STAT3 immunostaining measured by flow cytometry on PBMC from heterozygous Trp37* variant carriers and controls without (left) and with stimulation with IL-6 (right) (H). Time course of phospho-STAT3 by intracellular immunostaining in PBMC from heterozygous Trp37* variant carriers, non-carrier relatives, and healthy controls upon IL-6 or IL-21 stimulation. I Time course of phospho-STAT1 by intracellular immunostaining in PBMC from Trp37* variant carriers, non-carrier relatives, and healthy controls upon interferon-alpha, IL-6 or IL-21

Analysis of the p.Trp37* variant consequence on STAT3 transcript by in vitro exon-trapping in COS-7 cells showed that the variant may lead to alternative splicing events by splicing out the exon 2 and removing the start Methionine (Fig. 2D). Immunoblotting assessment of p.Trp37* STAT3 over-expression in STAT3-negative A4 cells revealed products at a lower molecular weight, consistent with re-initiation at positions M99 and M143, as previously described [21] (Fig. 2E).

The study on PBMCs from I:2, II:4, II:5 individuals by RNA-Seq demonstrated that both alleles (WT: C nucleotide and mutated: T nucleotide) are transcribed (Fig. 2F). However, a slight reduction in the proportion of the p.W37* allele is observed from 40% in individual I:2 to 30% in the index case (II:5) and her brother (II:4). Finally, STAT3 protein expression by immunoblotting or flow cytometry in PBMCs in carrier’s family members were not reduced when compared to healthy controls (Fig. 2G, Supplemental Fig. 1).

We thus assess the activation of STAT3 by measuring the phosphorylation level in all three heterozygous p.Trp37* STAT3 carriers (II:5-index, I:2, II:4) upon IL-6 and IL-21. All displayed 50% reduced STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation at different time-points after IL-6 or IL-21 stimulation (Fig. 2H) when compared with healthy controls or family members who are non-carrier of p.Trp37* allele (I:1, II:3). However, STAT1 phosphorylation was at a similar level after IFN-γ, IL-6, or IL-27 stimulation in the p.Trp37* cases and healthy controls (Fig. 2I).

Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Their Subpopulations

Lymphocyte immunophenotyping of patient II:5 was unremarkable. The response to pneumococcal polysaccharide antigens (Pneumovax®) was reduced with adequate responses to only 5 of the 10 tested serotypes [22]. While total CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cell counts were normal, effector memory populations were below normal range. Proportion of Th17 in the index case was reduced (9.3%, normal range 19–34%) but not absent. Th1 in turn was above normal range (45%, normal range 16–32%). IL-17 was also lower (0.47) than that observed in healthy control (0.72).

STAT3 p.Trp37* Transcriptional Activity

In STAT3 deficient A4 cells, the re-expression of full-length wild type STAT3 (WT) or full-length cDNA of the p.Trp37*variant (Trp37*_full-length in Fig. 3A) demonstrated increased luciferase activity, which is twice as the control for the Trp37*-full length variant. Instead, expression of a cDNA encoding only the first 37 AA of STAT3 had no detectable effect on activity (Trp37*_short, Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 2). To examine dominant negative effect, WT STAT3 or p.Trp37*_short (Fig. 3B,) in HEK293T which expressed endogenous STAT3 activity were transfected, and luciferase activity determined. A dose-dependent increase in luciferase activity was observed after IL-6 stimulation in HEK293T cells overexpressing WT STAT3. However, increasing amount of STAT3 Trp37*_short in HEK293T cells did not interfere with luciferase activity (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the STAT3 N-terminal 1 to 37 AA peptide does not display DN effect on transcriptional activity, in contrast to STAT3 p.Arg382Trp allele which has been reported to be amorphic and DN (Fig. 3A-C). Finally, HEK293T cells transfected with a control GFP expressing vector or with STAT3 p.Trp37*_short expressed similar levels of phosphorylated STAT3 and total STAT3 after IL-6 stimulation (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Luciferase activity (fold change) in STAT3 deficient A4 cells in non-transfected (mock), empty vector (EV), wild type STAT3 (WT), whole STAT3 sequence with p.Trp37* (W37*_Full-length), STAT3 N-terminal peptide amino acids 1–37 (W37*_short), or dominant negative STAT3 (Arg382Trp) (A). Luciferase activity (fold change) in STAT3 positive HEK293T cells in non-transfected (mock), empty vector (EV), wild type STAT3 (WT), whole STAT3 sequence with p.Trp37* (W37*_Full-length), STAT3 N-terminal peptide amino acids 1–37 (W37*_short), or dominant negative STAT3 (Arg382Trp). The y-axis represents STAT3 transcriptional activity levels normalized against unstimulated activity in EV-transformed cells. Each dot represents a biological replicate obtained from technical replicates. B Luciferase activity (fold change) in HEK293T cells with endogenous STAT3 expressing an increasing amount of wild type (WT) or whole STAT3 sequence with p. Trp37X or dominant negative STAT3 (Arg382Trp). D HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP and MAC-tag-N vector containing STAT3 p.Trp37*_short using calcium phosphate. Two days after transfection, cells were stimulated with or without IL-6 for 30 min. Cells were collected for further Western blot detections of tyrosine phosphorylated STAT3 and total STAT3. Immunoblots from two independent experiments are shown

Expression Profiles in STAT3 p.Trp37* PBMCs

Since seemingly conflicting results of reduced phosphorylated STAT3 in vivo and isomorphic transcriptional activity of the p.Trp37* STAT3 in vitro were observed, we compared the transcriptional expression from unstimulated PBMCs obtained from the index to a patient with confirmed STAT3 GOF (STAT3 p.Arg278His) normalised by 2 unstimulated healthy individuals [7]. In STAT3 p.Arg278His GOF PBMCs, high CXCL10, IFNG and STAT1 expression was observed. Similar changes indicative of STAT3 GOF were not seen in the expression profile of STAT3 p.Trp37* PBMCs from the index case (Fig. 4). Both these results and the clinical phenotype thus argued against STAT3 GOF phenotype.

Fig. 4.

Selected immunological expression profiles of index PBMCs. mRNA fold changes compared to healthy controls in unstimulated index STAT3 p.Trp37* and Arg278His (STAT3 GOF) PBMCs of seven IFN-regulated genes (A), type II IFN (B), inflammasome (C), NF-κB pathway (D), JAK/STAT pathway (E), and interleukins (F) related genes. Mean of three measurements together with SD is presented

Stimulated PBMCs from three p.Trp37* variant carriers and their controls underwent RNA-Seq transcriptomic analyses. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the transcriptomes of p.Trp37* positive cases were rather similar when compared to matched controls, with minor differences between the expression profiles of the index I:2 and her control (Fig. 5A). Group comparison of the 3 family members versus the 3 controls only generated expression changes of 20 genes (Supplemental Table 4). Among them, a significant up-regulation of CXCL9 in the 3 carriers has been found, a gene previously reported as upregulated in T-cell from CD4-conditional STAT3-deficient mice [23]. Since the other two family members are healthy, and they do not suffer from infections or HIES phenotype, we focused on comparison of expression profiles between the index patient and her control. Of the 15,596 genes detected in IL-6 stimulated PBMCs from the index and her control sample, expression of 301 genes was reduced in IL-6 stimulated p.Trp37* PBMCs and expression of 315 genes was enhanced when compared with the control, suggesting the possibility of neomorphic effects (Fig. 5B, Supplemental Table 5). Importantly, as shown in Fig. 2F, the RNA-Seq results performed from primary patient cells have confirmed the presence of the reported variant. Notably, the RNA-Seq data showed no changes of total STAT3 mRNA expression level in the three heterozygous p.Trp37* variant family carriers versus controls (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the Th17 differentiation pathway was dissimilar (Fig. 5D), with reduced expression of RORC, TBX21, IFNG and HLA-DRB5 in the patient’s sample (Fig. 5E, 5F) [24]. Expression of 10 selected genes, including FOXP3 and IKAROS Family Zinc Finger 4 (IKZF4) was significantly upregulated in the patient’s sample compared with her control (Fig. 5D-F). qPCR further confirmed the increased expression of FOXP3 and reduced RORC and TBX21 in the index patient’s IL-6 stimulated PBMCs [25]. Finally, we explored whether the variant could create a new allele by quantifying the STAT3 cDNA expression using probes targeting the 5’ (exon 2) or the middle (exon 14) of STAT3 by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 5G, no difference using both probes were observed on the PBMCs from the index or compared to her control.

Fig. 5.

Transcriptomics analysis reveals distinct gene expression profiles in cases with STAT3 p.Trp37* mutation. A PCA plot of transcriptomes of IL-6 stimulated PBMCs from three STAT3 p.Trp37* variant positive cases and sex/age matched controls X-axis represents the contributor rate of the first component. Y-axis represents the contributor rate of the second component. Points represent each sample. Ellipses were drawn manually. B The number of differentially expressed genes from IL-6 stimulated PBMCs from three STAT3 p. Trp37X mutated cases and sex/age matched controls are shown. C STAT3 mRNA expression of the three family members with the STAT3 p.W37X mutation and their controls from RNA-Seq data obtained from IL-6 stimulated PBMCs. D KEGG pathway analysis was performed on up-regulated and down-regulated genes in IL-6 stimulated PBMCs from the indexed patient versus her control comparison. The pathways presented in the plot are significantly enriched; The colour indicates the q-value, the lower q-value indicates the more significant enrichment. Point size indicates DEG number. The larger the value of the rich factor, the more significant enrichment. E Heatmap showing the log fold change values of selected genes significantly changed in IL-6 stimulated PBMC from patient versus control (F). Quantitative RT-PCR detections of Foxp3, RORC and TBX21, key transcription factors for Treg, Th17 and Th1 cells respectively. G Quantitative RT-PCR mRNA expression using 5’UTR probe (upstream the W37* variant), and probe in the middle of the transcript (downstream the W37* variant) the p.W37X mutation site respectively, fragments of STAT3. EF1α was used as endogenous control in all the qPCR detections

Discussion

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is a rare condition that can be found in association with lung diseases such as tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis [26]. In addition to severely immunosuppressed individuals, pulmonary aspergillosis may also affect critically ill patients especially among the elderly [27]. However, the young index patient described here had no history of lung disease, infection susceptibility or immunosuppressive condition. Instead, the CPA in this case associates with novel and rare STAT3 p.Trp37* NTD premature termination mutation; only two individuals with similar STAT3 NTD variant have been identified in gnomAD genetic database (p.Gln20Ter, p.Glu39Ter; allele frequency 1.59 × 10–6). Clinical presentation or immunological findings associated with such NTD variants are not well understood. In contrast to STAT3 LOF or GOF variants, incomplete clinical penetrance and lack of classical phenotype are evident in this family [4]. Natarajan et al. reported a case of STAT3 haploinsufficiency with reduced amount of STAT3 caused by a splice-site mutation and nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the affected allele [10]. In contrast, the p.Trp37* mutant mRNA species were present, and the total STAT3 protein level was not reduced in the PBMCs collected from the patient. In summary, the genetics and clinical presentation in the case described here are suggestive of unique phenotype.

Disruption of the STAT3 NTD caused by p.Trp37* allele may lead to several biological consequences. Obviously, the mutation can be expected to disturb the STAT3 NTD cooperative DNA binding, nuclear translocation, and protein–protein interactions including dimerization of STAT3 [13, 28]. Although the p.Trp37* disrupts the NTD and the short 37 AA peptide is not DN in experimental models [12], the premature termination leads in an in vitro assay to re-initiation products with higher biological activity. Despite the high activity in vitro, the patient’s clinical and immunological phenotype differs from STAT3 GOF. While the p.Trp37* allele does not have DN effect on transcriptional activity in vitro cell culture model, this combination of alleles disturbs the WT STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation and Th17 cell maturation, mimicking DN STAT3 deficiency. Although we are not able to define the exact biological mechanism, the STAT3 p.Trp37* generates a novel combination of disturbed STAT3 biology.

In summary, we report a patient with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and a heterozygous STAT3 NTD premature termination p.Trp37* LOF allele. She presents with a novel combination of mixed biological and clinical features. Clinical and biological information involving the STAT3 NTD LOF variants in literature is limited; the case presented here deviates from previously reported DN STAT3 HIES, or STAT3 GOF cases. Incomplete clinical penetrance in family members suggest that external causes such as exposure to an aggressive Aspergillus strain or additional genetic components may have contributed to this condition.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(XLSX 48.8 KB)

(PDF 186 KB)

Author Contributions

S.L.S., T.A., V.G., S.K., K.P. experiments, manuscript preparation. T.M., F.Y., O.K. and L.T. clinical care, manuscript preparation. M.K. and J.S. genetic analysis, manuscript preparation. E.L.B. pathology examination. A.J. radiology diagnosis. B. B., M.R.J. S., M.V., J.L.C. expertise, hypothesis formation, manuscript preparation. T.H. clinical care, interpretation of the results, manuscript preparation, Z. C. interpreted the results, manuscript preparation.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Oulu (including Oulu University Hospital). The Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases is supported by the Job Research Foundation, the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award program (UL1TR001866); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P01AI061093); the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the “Investments for the Future” ANR program (ANR-10-IAHU-01), the Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID), the “PNEUMOPID” project (ANR 14-CE15-0009–01),“and the”ProLegio” project (ANR-15-CE17-0014); the French Foundation for Medical Research (EQU201903007798); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; The Rockefeller University; the St. Giles Foundation; Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale; and the Université de Paris. M.R.J.S. and T.H. were funded by Sigrid Juselius Foundation, M.R.J.S. also by Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation and HUS Pediatric Research Center and HUS Group hospital research funds. Z.C. was funded by Academy of Finland, decision number 325965.

Data Availability

Available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Oulu University Hospital.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all individuals.

Consent for Publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all individuals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Timo Hautala and Zhi Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Timo Hautala, Email: Timo.Hautala@oulu.fi.

Zhi Chen, Email: zhi.chen@oulu.fi.

References

- 1.Forbes LR, Milner J, Haddad E. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3: a year in review. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23:23–7. 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asano T, Khourieh J, Zhang P, Rapaport F, Spaan AN, Li J, et al. Human STAT3 variants underlie autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome by negative dominance. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2021;218. 10.1084/jem.20202592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Woellner C, Gertz EM, Schäffer AA, Lagos M, Perro M, Glocker E-O, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and diagnostic guidelines for hyper-IgE syndrome. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;125:424-432.e8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsilifis C, Freeman AF, Gennery AR. STAT3 Hyper-IgE Syndrome—an Update and Unanswered Questions. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41:864–80. 10.1007/s10875-021-01051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yong PF, Freeman AF, Engelhardt KR, Holland S, Puck JM, Grimbacher B. An update on the hyper-IgE syndromes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:228. 10.1186/ar4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanagan SE, Haapaniemi E, Russell MA, Caswell R, Allen HL, De Franco E, et al. Activating germline mutations in STAT3 cause early-onset multi-organ autoimmune disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46:812–4. 10.1038/ng.3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leiding JW, Vogel TP, Santarlas VGJ, Mhaskar R, Smith MR, Carisey A, et al. Monogenic early-onset lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity: Natural history of STAT3 gain-of-function syndrome. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2022. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Göös H, Fogarty CL, Sahu B, Plagnol V, Rajamäki K, Nurmi K, et al. Gain-of-function CEBPE mutation causes noncanonical autoinflammatory inflammasomopathy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;144:1364–76. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lodi L, Faletti LE, Maccari ME, Consonni F, Groß M, Pagnini I, et al. STAT3-confusion-of-function: Beyond the loss and gain dualism. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2022;150:1237-1241.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natarajan M, Hsu AP, Weinreich MA, Zhang Y, Niemela JE, Butman JA, et al. Aspergillosis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and allergic rhinitis in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 haploinsufficiency. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2018;142:993-997.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu AP, Korzeniowska A, Aguilar CC, Gu J, Karlins E, Oler AJ, et al. Immunogenetics associated with severe coccidioidomycosis. JCI Insight 2022;7. 10.1172/jci.insight.159491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mohr A, Fahrenkamp D, Rinis N, Müller-Newen G. Dominant-negative activity of the STAT3-Y705F mutant depends on the N-terminal domain. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2013;11:83. 10.1186/1478-811X-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogt M, Domoszlai T, Kleshchanok D, Lehmann S, Schmitt A, Poli V, et al. The role of the N-terminal domain in dimerization and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of latent STAT3. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:900–9. 10.1242/jcs.072520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaustio M, Nayebzadeh N, Hinttala R, Tapiainen T, Åström P, Mamia K, et al. Loss of DIAPH1 causes SCBMS, combined immunodeficiency, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2021;148:599–611. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, et al. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell. 2019;176:535-548.e24. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckler AJ, Chang DD, Graw SL, Brook JD, Haber DA, Sharp PA, et al. Exon amplification: a strategy to isolate mammalian genes based on RNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:4005–9. 10.1073/pnas.88.9.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burn TC, Connors TD, Klinger KW, Landes GM. Increased exon-trapping efficiency through modifications to the pSPL3 splicing vector. Gene. 1995;161:183–7. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00223-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keskitalo S, Haapaniemi E, Einarsdottir E, Rajamäki K, Heikkilä H, Ilander M, et al. Novel TMEM173 Mutation and the Role of Disease Modifying Alleles. Frontiers in Immunology 2019;10. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Audic S, Claverie J-M. The Significance of Digital Gene Expression Profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–95. 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Salokas K, Tamene F, Jiu Y, Weldatsadik RG, Öhman T, et al. An AP-MS- and BioID-compatible MAC-tag enables comprehensive mapping of protein interactions and subcellular localizations. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1188. 10.1038/s41467-018-03523-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahmarvand N, Nagy A, Shahryari J, Ohgami RS. Mutations in the signal transducer and activator of transcription family of genes in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:926–33. 10.1111/cas.13525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selenius JS, Martelius T, Pikkarainen S, Siitonen S, Mattila E, Pietikäinen R, et al. Unexpectedly High Prevalence of Common Variable Immunodeficiency in Finland. Frontiers in Immunology 2017;8. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yue C, Shen S, Deng J, Priceman SJ, Li W, Huang A, et al. STAT3 in CD8+ T Cells Inhibits Their Tumor Accumulation by Downregulating CXCR3/CXCL10 Axis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:864–70. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwata S, Mikami Y, Sun H-W, Brooks SR, Jankovic D, Hirahara K, et al. The Transcription Factor T-bet Limits Amplification of Type I IFN Transcriptome and Circuitry in T Helper 1 Cells. Immunity. 2017;46:983-991.e4. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell MD, Read KA, Sreekumar BK, Oestreich KJ. Ikaros Zinc Finger Transcription Factors: Regulators of Cytokine Signaling Pathways and CD4+ T Helper Cell Differentiation. Frontiers in Immunology 2019;10. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Smith NL, Denning DW. Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:865. 10.1183/09031936.00054810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaragoza R, Sole-Violan J, Cusack R, Rodriguez A, Reyes LF, Martin-Loeches I. Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Not Only a Disease Affecting Immunosuppressed Patients. Diagnostics 2023;13. 10.3390/diagnostics13030440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hu T, Yeh JE, Pinello L, Jacob J, Chakravarthy S, Yuan G-C, et al. Impact of the N-Terminal Domain of STAT3 in STAT3-Dependent Transcriptional Activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3284–300. 10.1128/MCB.00060-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX 48.8 KB)

(PDF 186 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.