Abstract

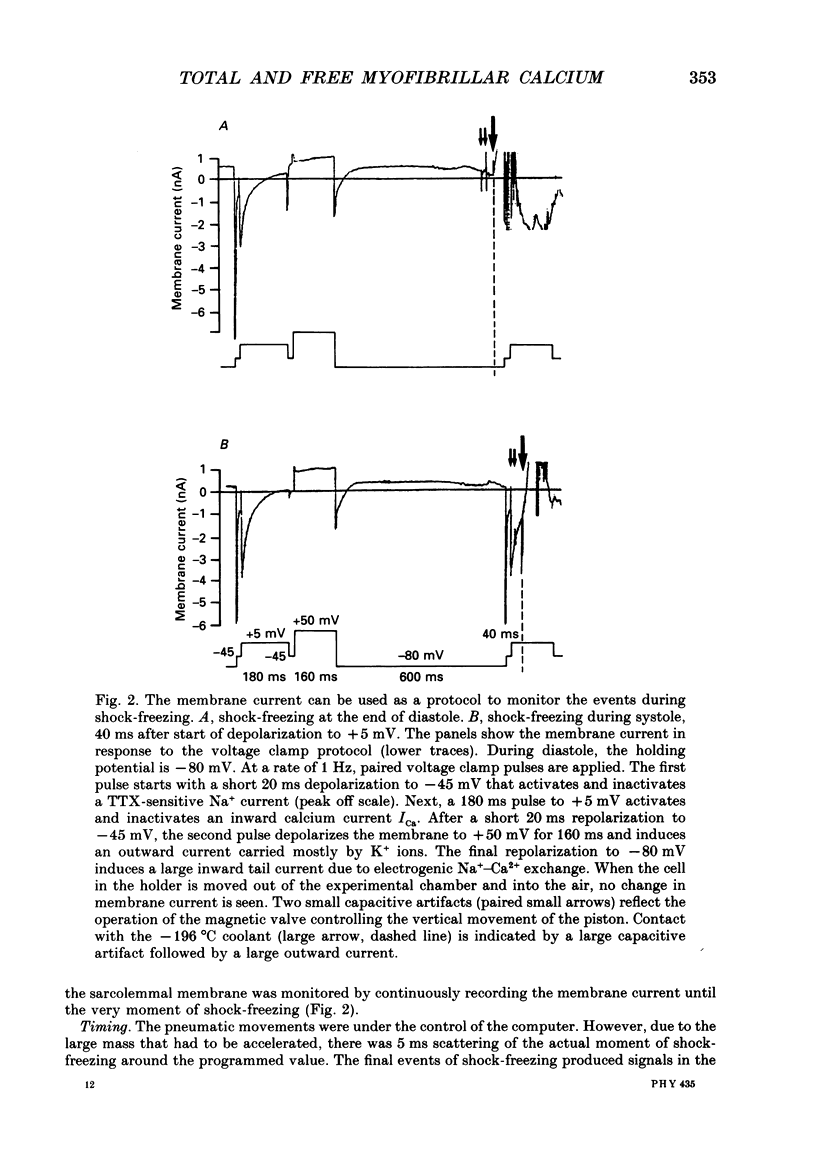

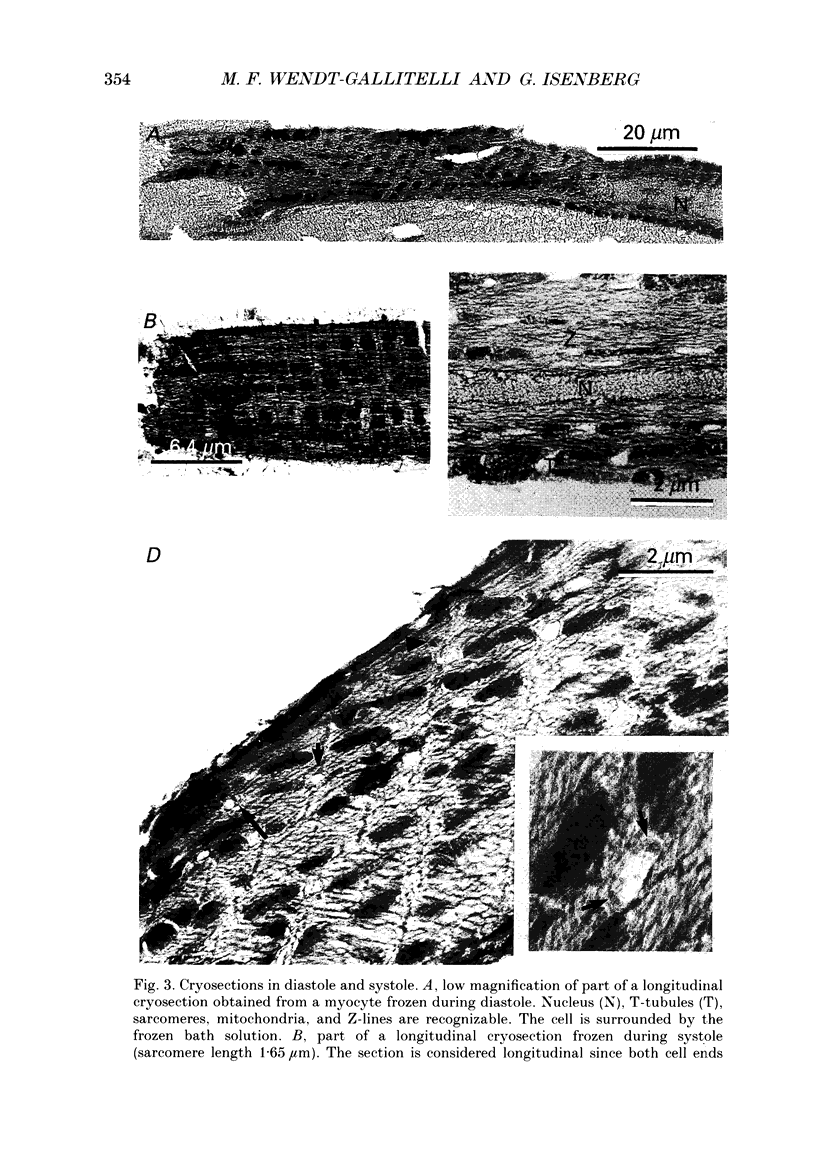

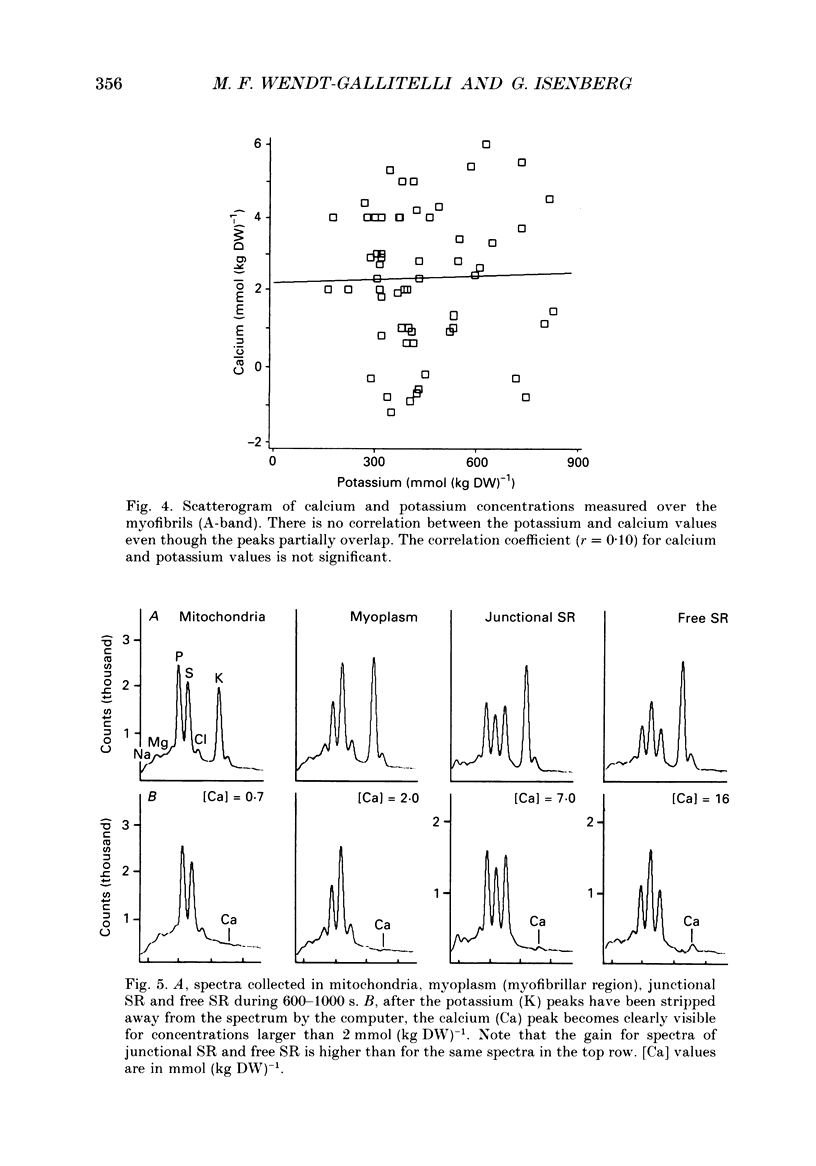

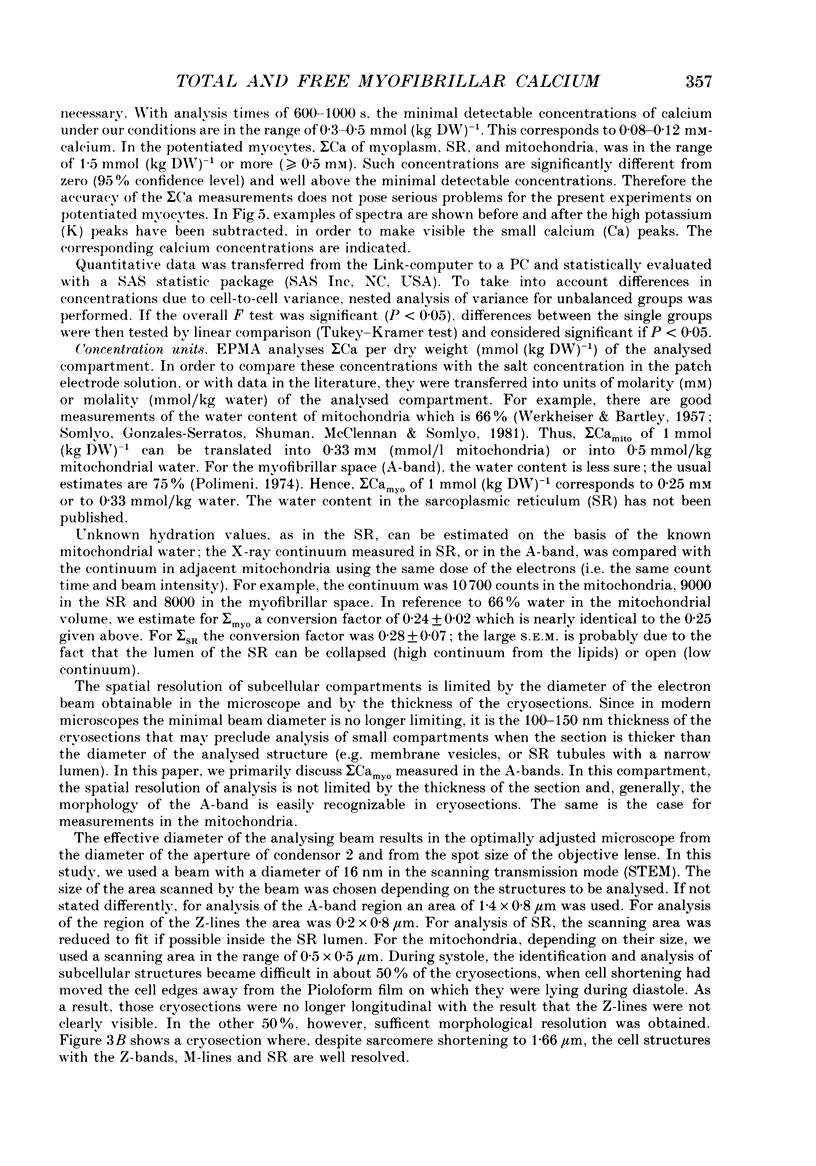

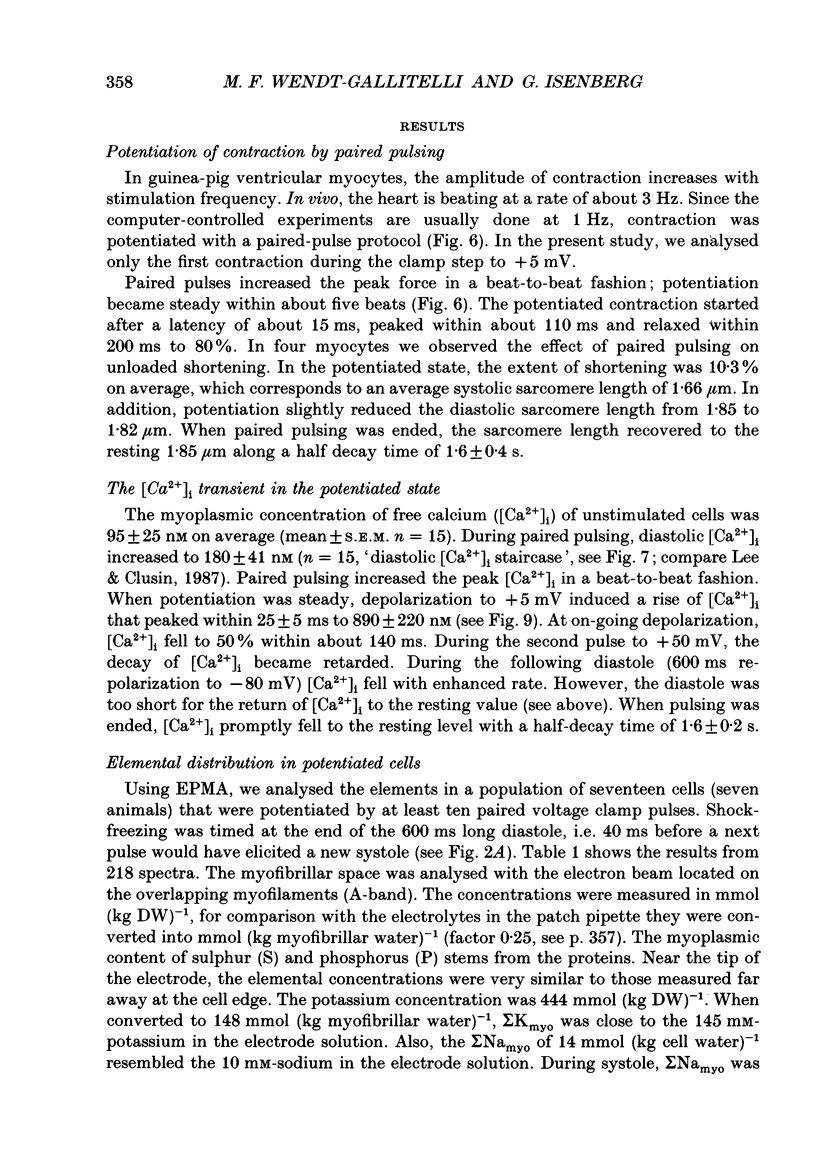

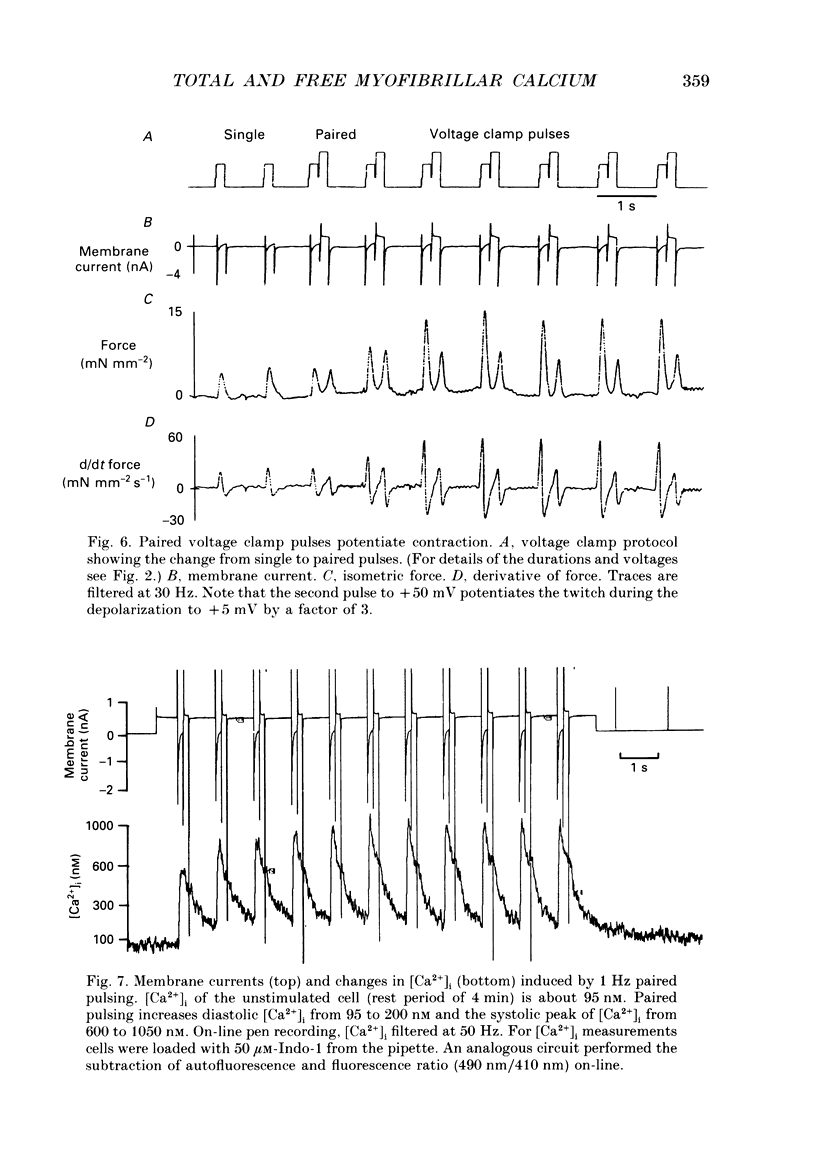

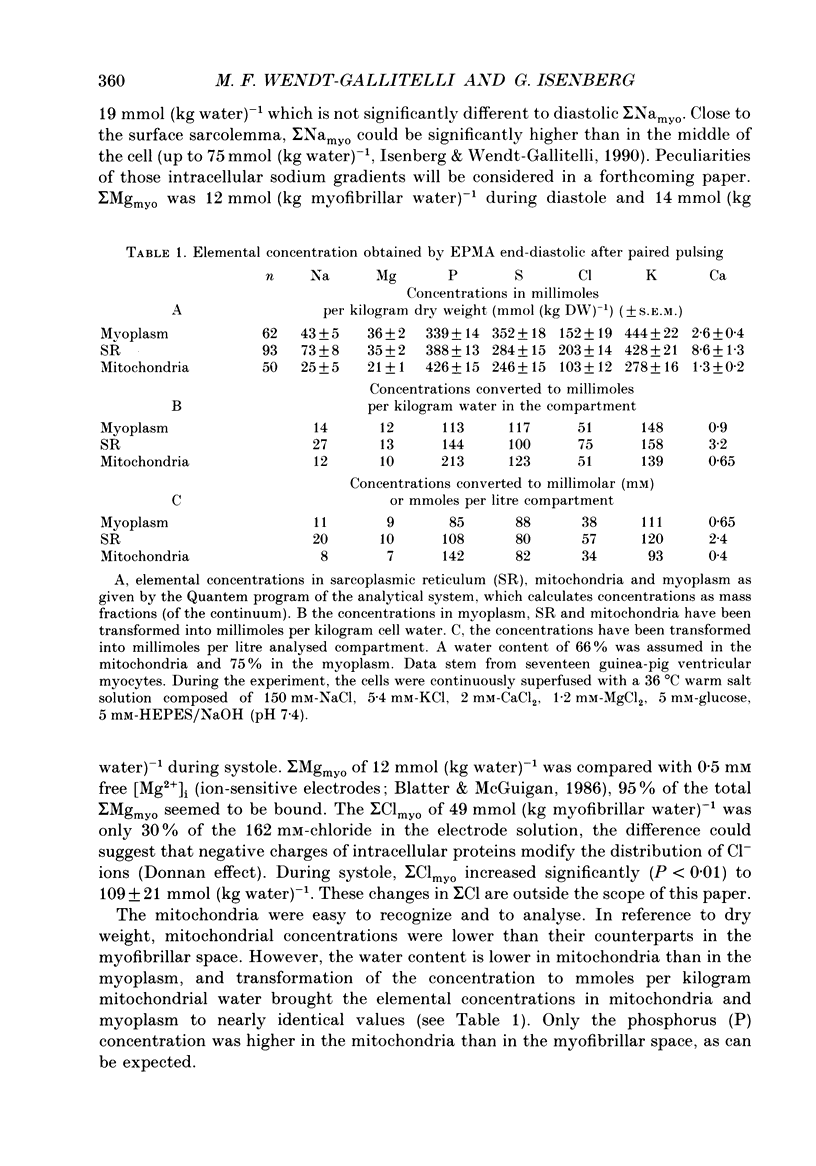

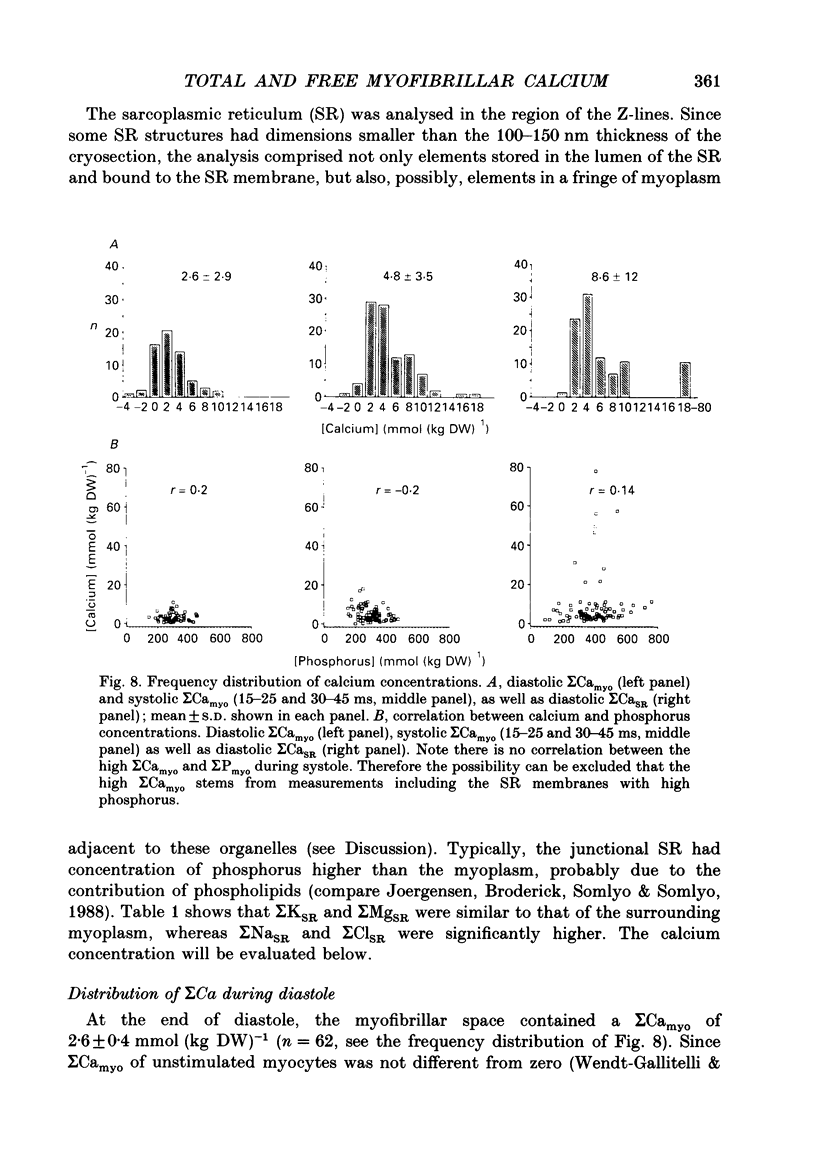

1. At 36 degrees C and 2 mM [Ca2+]o single guinea-pig ventricular myocytes were voltage clamped with patch electrodes. With a paired-pulse protocol applied at 1 Hz, a first pulse to +5 mV was followed by a second pulse to +50 mV. When paired pulsing had potentiated the contraction to the maximum, the cells were shock-frozen for electron-probe microanalysis (EPMA). Shock-freezing was timed at the end of diastole (-80 mV) or at different times during systole (+5 mV). 2. The same paired-pulse protocol was applied to another group of myocytes from which contraction and [Ca2+]i was estimated by microfluospectroscopy (50 microM-Na5-Indo-1). Potentiation moderately reduced diastolic sarcomere length from 1.85 to 1.82 microns and increased diastolic [Ca2+]i from about 95 to 180 nM. In potentiated cells, during the first pulse, contraction peaked within 128 +/- 25 ms after start of depolarization. [Ca2+]i peaked within 25 ms to 890 +/- 220 nM (mean +/- S.E.M.) and fell within 100 ms to about 450 nM. 3. Sigma Camyo, the total calcium concentration in the overlapping myofilaments (A-band), was measured by EPMA in seventeen potentiated myocytes. During diastole, sigma Camyo was 2.6 +/- 0.4 mmol (kg dry weight (DW]-1 which can be converted to 0.65 mM (mmoles per litre myofibrillar space). Since [Ca2+]i was 180 nM, we estimate that 99.97% of total calcium is bound. 4. A time course for systolic sigma Camyo was determined by shock-freezing thirteen cells at different times after start of depolarization to +5 mV. Sigma Camyo was 5.5 +/- 0.3 mmol (kg DW)-1 (1.4 mM) after 15-25 ms, 4.6 +/- 0.5 mmol (kg DW)-1 (1.1 mM) after 30-45 ms, and 3.1 mmol (kg DW)-1 (0.8 mM) after 60-120 ms. The fast time course of sigma Camyo suggests that calcium binds to and unbinds from troponin C at a fast rate. Hence, it is the slow kinetics of the cross-bridges that determines the 130 ms time-to-peak shortening. 5. Mitochondria of potentiated cells contained during diastole a total calcium concentration, sigma Camito, of 1.3 +/- 0.2 mmol (kg DW)-1 (0.4 mM). During the initial 15-25 ms of systole, sigma Camito did not change, however, during 30-45 ms sigma Camito rose to 3.7 +/- 0.5 mmol (kg DW)-1 (1.2 mM). The data suggest that sigma Camito can follow sigma Camyo with some delay, thereby participating in both slow diastolic and fast systolic changes in total calcium (sigma Ca), at least under the given conditions.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

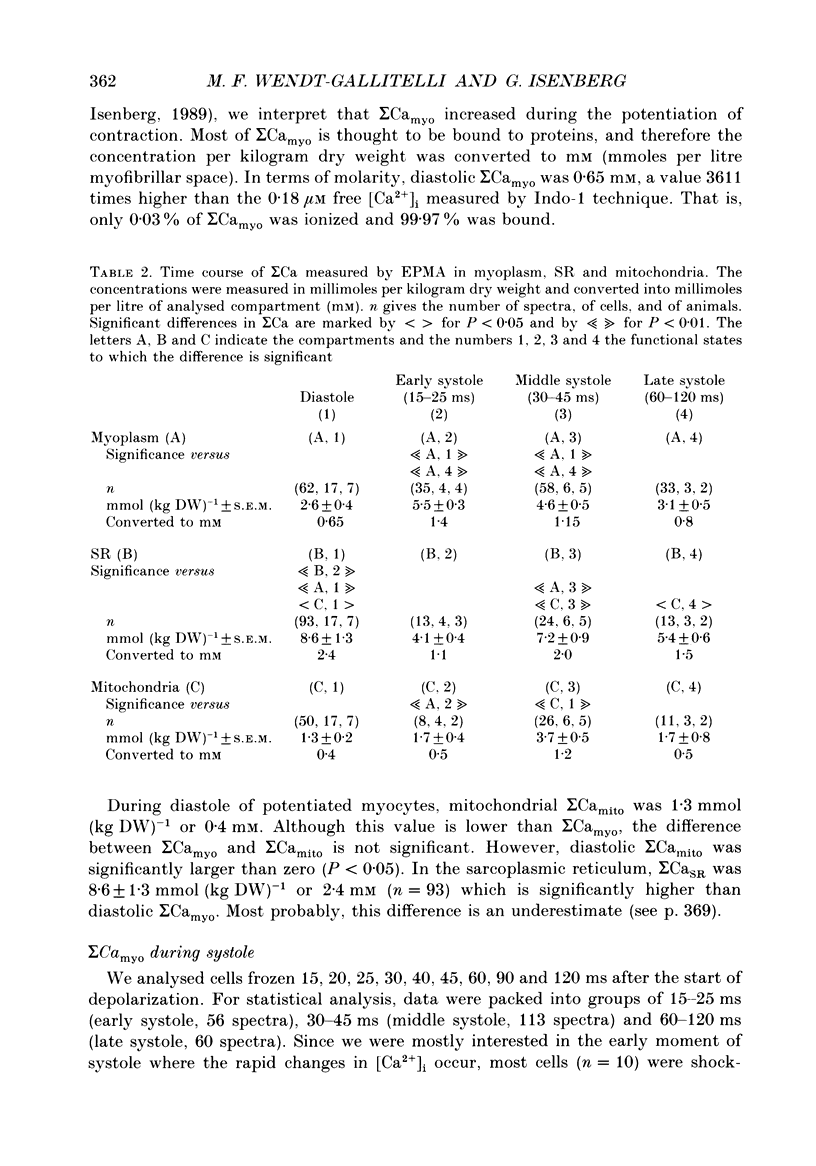

PDF

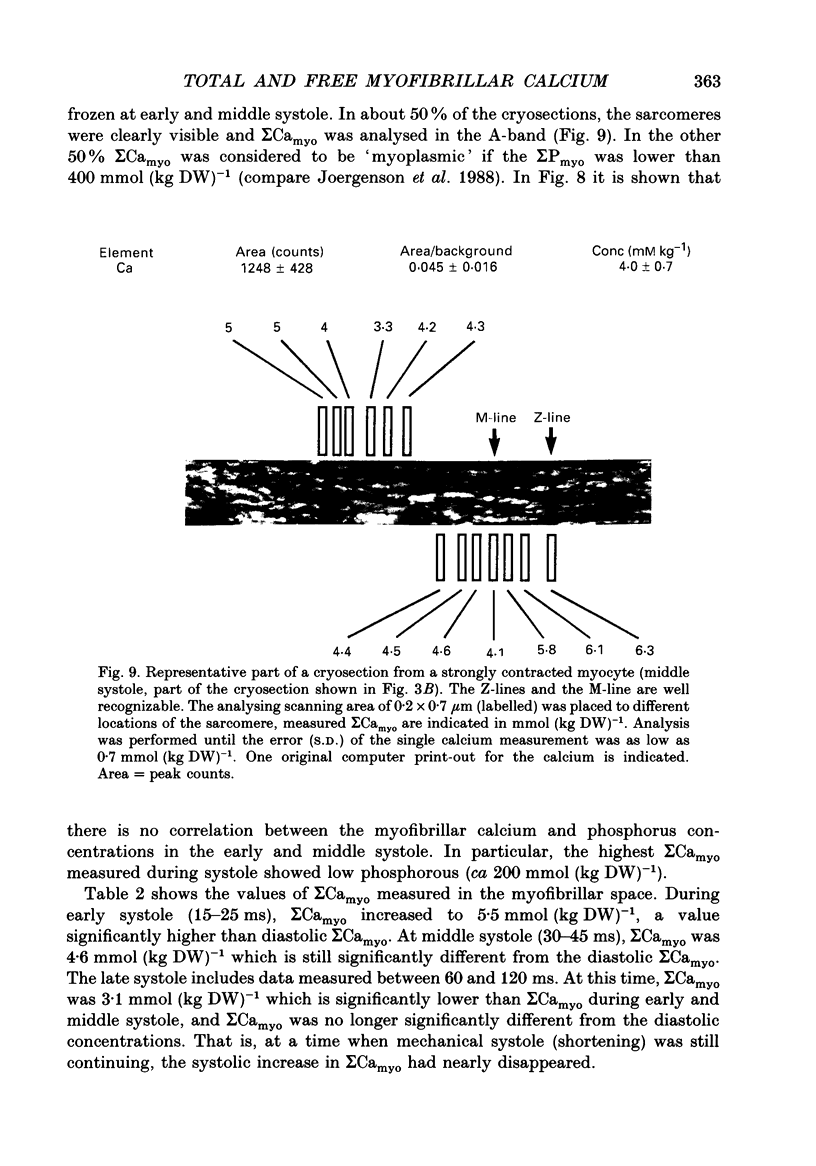

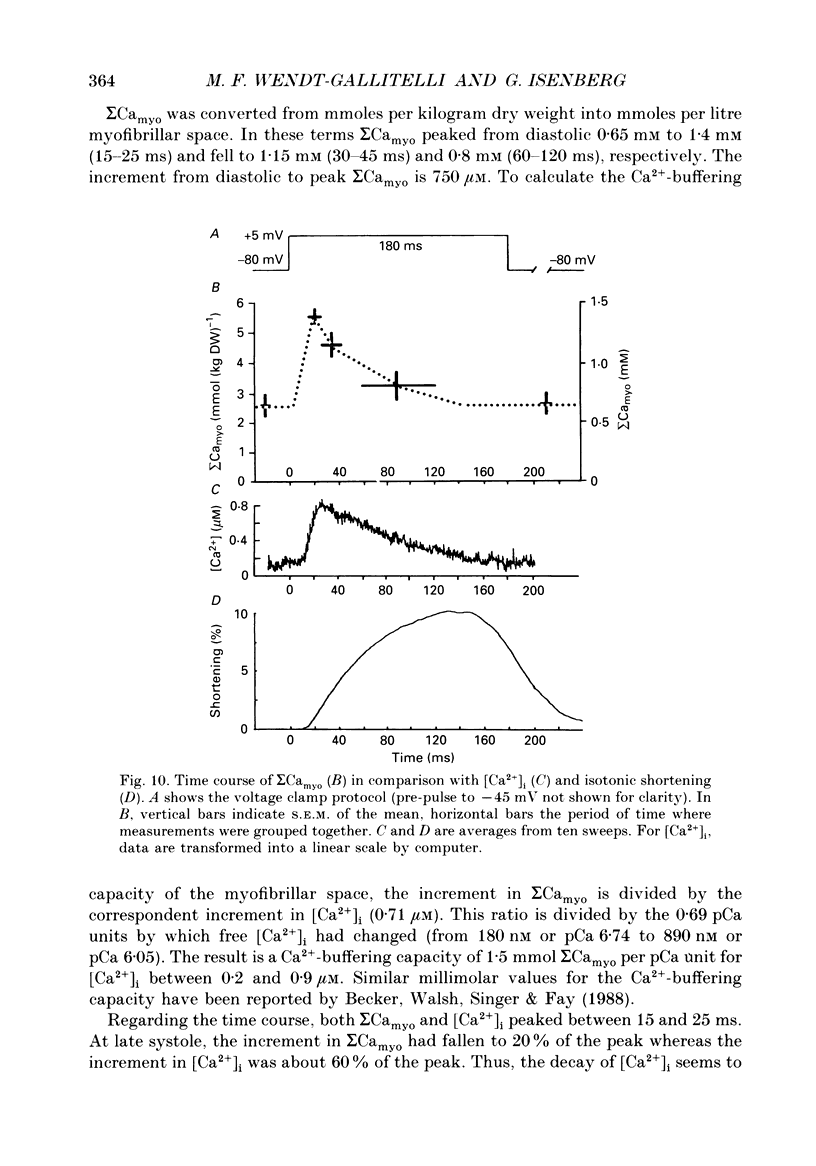

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen D. G., Eisner D. A., Pirolo J. S., Smith G. L. The relationship between intracellular calcium and contraction in calcium-overloaded ferret papillary muscles. J Physiol. 1985 Jul;364:169–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor S. M., Hollingworth S. Fura-2 calcium transients in frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1988 Sep;403:151–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckelmann D. J., Wier W. G. Mechanism of release of calcium from sarcoplasmic reticulum of guinea-pig cardiac cells. J Physiol. 1988 Nov;405:233–255. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter L. A., McGuigan J. A. Free intracellular magnesium concentration in ferret ventricular muscle measured with ion selective micro-electrodes. Q J Exp Physiol. 1986 Jul;71(3):467–473. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1986.sp003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond M., Jaraki A. R., Disch C. H., Healy B. P. Subcellular calcium content in cardiomyopathic hamster hearts in vivo: an electron probe study. Circ Res. 1989 May;64(5):1001–1012. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünger R., Permanetter B. Parallel stimulation by Ca2+ of inotropism and pyruvate dehydrogenase in perfused heart. Am J Physiol. 1984 Jul;247(1 Pt 1):C45–C52. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.247.1.C45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert G., Cleemann L., Morad M. Epinephrine enhances Ca2+ current-regulated Ca2+ release and Ca2+ reuptake in rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Mar;85(6):2009–2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M., Moser R., Lüdi H., Carafoli E. The interrelations between the transport of sodium and calcium in mitochondria of various mammalian tissues. Eur J Biochem. 1978 Jan 2;82(1):25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb11993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daut J., Elzinga G. Heat production of quiescent ventricular trabeculae isolated from guinea-pig heart. J Physiol. 1988 Apr;398:259–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jul;245(1):C1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry C. H., Harding D. P., Miller D. J. Non-mitochondrial calcium ion regulation in rat ventricular myocytes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1989 Feb 22;236(1282):53–77. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1989.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry C. H., Powell T., Twist V. W., Ward J. P. Net calcium exchange in adult rat ventricular myocytes: an assessment of mitochondrial calcium accumulating capacity. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1984 Dec 22;223(1231):223–238. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich V Y. a., Isenberg G. Depolarization-mediated intracellular calcium transients in isolated smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1991 Apr;435:187–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 25;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter T. E., Pfeiffer D. R. Mechanisms by which mitochondria transport calcium. Am J Physiol. 1990 May;258(5 Pt 1):C755–C786. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.5.C755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. Biological X-ray microanalysis. J Microsc. 1979 Sep;117(1):145–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1979.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbach W., Oetliker H. Energetics and electrogenicity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump. Annu Rev Physiol. 1983;45:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.45.030183.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley H. E., Faruqi A. R. Time-resolved X-ray diffraction studies on vertebrate striated muscle. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1983;12:381–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.12.060183.002121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg G. Ca entry and contraction as studied in isolated bovine ventricular myocytes. Z Naturforsch C. 1982 May-Jun;37(5-6):502–512. doi: 10.1515/znc-1982-5-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen A. O., Broderick R., Somlyo A. P., Somlyo A. V. Two structurally distinct calcium storage sites in rat cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum: an electron microprobe analysis study. Circ Res. 1988 Dec;63(6):1060–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Clusin W. T. Cytosolic calcium staircase in cultured myocardial cells. Circ Res. 1987 Dec;61(6):934–939. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewartowski B., Pytkowski B. On the subcellular localisation of calcium fraction correlating with contractile force of guinea-pig ventricular myocardium. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1987;46(8-9):S345–S350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. G., Halestrap A. P., Denton R. M. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1990 Apr;70(2):391–425. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillin-Wood J., Wolkowicz P. E., Chu A., Tate C. A., Goldstein M. A., Entman M. L. Calcium uptake by two preparations of mitochondria from heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980 Jul 8;591(2):251–265. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicchitta C. V., Williamson J. R. Spermine. A regulator of mitochondrial calcium cycling. J Biol Chem. 1984 Nov 10;259(21):12978–12983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page E. Quantitative ultrastructural analysis in cardiac membrane physiology. Am J Physiol. 1978 Nov;235(5):C147–C158. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1978.235.5.C147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B. S., Solaro R. J. Calcium-binding properties of troponin C in detergent-skinned heart muscle fibers. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jun 5;262(16):7839–7849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson L., Rosengren E. Polyamine metabolism in muscles of mice and rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1983 Mar;117(3):457–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni P. I. Extracellular space and ionic distribution in rat ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1974 Sep;227(3):676–683. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.3.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson S. P., Johnson J. D., Potter J. D. The time-course of Ca2+ exchange with calmodulin, troponin, parvalbumin, and myosin in response to transient increases in Ca2+. Biophys J. 1981 Jun;34(3):559–569. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd N., Vornanen M., Isenberg G. Force measurements from voltage-clamped guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1990 Feb;258(2 Pt 2):H452–H459. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Wise R. M., Shiner J. S., Briggs F. N. Calcium requirements for cardiac myofibrillar activation. Circ Res. 1974 Apr;34(4):525–530. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo A. P., Bond M., Somlyo A. V. Calcium content of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in liver frozen rapidly in vivo. Nature. 1985 Apr 18;314(6012):622–625. doi: 10.1038/314622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo A. V., Gonzalez-Serratos H. G., Shuman H., McClellan G., Somlyo A. P. Calcium release and ionic changes in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of tetanized muscle: an electron-probe study. J Cell Biol. 1981 Sep;90(3):577–594. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERKHEISER W. C., BARTLEY W. The study of steady-state concentrations of internal solutes of mitochondria by rapid centrifugal transfer to a fixation medium. Biochem J. 1957 May;66(1):79–91. doi: 10.1042/bj0660079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt-Gallitelli M. F. Ca-pools involved in the regulation of cardiac contraction under positive inotropy. X-ray microanalysis on rapidly-frozen ventricular muscles of guinea-pig. Basic Res Cardiol. 1986;81 (Suppl 1):25–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11374-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt-Gallitelli M. F., Isenberg G. X-ray microanalysis of single cardiac myocytes frozen under voltage-clamp conditions. Am J Physiol. 1989 Feb;256(2 Pt 2):H574–H583. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.2.H574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt-Gallitelli M. F., Jacob R., Wolburg H. Intracellular membranes as boundaries for ionic distribution. In situ elemental distribution in guinea pig heart muscle in different defined electro-mechanical coupling states. Z Naturforsch C. 1982 Jul-Aug;37(7-8):712–720. doi: 10.1515/znc-1982-7-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt-Gallitelli M. F. Presystolic calcium-loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum influences time to peak force of contraction. X-ray microanalysis on rapidly frozen guinea-pig ventricular muscle preparations. Basic Res Cardiol. 1985 Nov-Dec;80(6):617–625. doi: 10.1007/BF01907860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler-Clark E. S., Tormey J. M. Electron probe x-ray microanalysis of sarcolemma and junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum in rabbit papillary muscles: low sodium-induced calcium alterations. Circ Res. 1987 Feb;60(2):246–250. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- duBell W. H., Houser S. R. Voltage and beat dependence of Ca2+ transient in feline ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1989 Sep;257(3 Pt 2):H746–H759. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.3.H746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]