Abstract

A novel cypovirus has been isolated from the mosquito Uranotaenia sapphirina (UsCPV) and shown to cause a chronic infection confined to the cytoplasm of epithelial cells of the gastric ceca and posterior stomach. The production of large numbers of virions and inclusion bodies and their arrangement into paracrystalline arrays gives the gut of infected insects a distinctive blue iridescence. The virions, which were examined by electron microscopy, are icosahedral (55 to 65 nm in diameter) with a central core that is surrounded by a single capsid layer. They are usually packaged individually within cubic inclusion bodies (polyhedra, ∼100 nm across), although two to eight virus particles were sometimes occluded together. The virus was experimentally transmitted per os to several mosquito species. The transmission rate was enhanced by the presence of magnesium ions but was inhibited by calcium ions. Most of the infected larvae survived to adulthood, and the adults retained the infection. Electrophoretic analysis of the UsCPV genome segments (using 1% agarose gels) generated a migration pattern (electropherotype) that is different from those of the 16 Cypovirus species already recognized. UsCPV genome segment 10 (Seg-10) showed no significant nucleotide sequence similarity to the corresponding segment of the other cypoviruses that have previously been analyzed, and it has different “conserved” termini. A BLAST search of the UsCPV deduced amino acid sequence also showed little similarity to Antheraea mylitta CPV-4 (67 of 290 [23%]) or Choristoneura fumiferana CPV-16 (33 of 111 [29%]). We conclude that UsCPV should be recognized as a member of a new Cypovirus species (Cypovirus 17, strain UsCPV-17).

The first report of an occluded cytoplasmic insect virus was from the midgut epithelial cells of the silkworm Bombyx mori (16). The virus was subsequently identified as a cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CPV) to distinguish it from the nuclear polyhedrosis viruses already recognized (27). CPVs are commonly isolated from insects, mainly from Lepidoptera and occasionally from Diptera or Hymenoptera, but only rarely from Coleoptera or Neuroptera (15).

Cytoplasmic polyhedrosis viruses usually have a ten-segmented double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome and are classified as members of the genus Cypovirus within the family Reoviridae (14, 20). Different cypovirus “types” were initially identified on the basis of differences in the migration patterns of their genome segments during polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, i.e., electropherotypes (22). Subsequent studies showed a good correlation between electropherotype and the grouping of strains on the basis of serological properties (18) or RNA cross-hybridization (17, 20). It has recently been shown that, in addition to the RNA migration patterns, nucleotide sequences, for example, those of genome segment 10 (Seg-10; the polyhedrin gene), can be used to distinguish different Cypovirus species (20). Sixteen Cypovirus species (types) are currently recognized, all from lepidopteran hosts (20).

Numerous viruses (isolated before the recognition of the genus Cypovirus) from the larvae of 20 different species of mosquitoes (representing nine different genera) were identified as CPVs based on similarities to viruses from Lepidoptera (12). These similarities included virion structure, the presence of inclusion bodies (polyhedra), and chronic infection in the cytoplasm of midgut epithelial cells. There were also three reports of CPVs from the midgut epithelium of adult mosquitoes (7, 8, 11). However, there was no further biophysical or biochemical analyses of these mosquito cypoviruses.

We report an analysis of the biology, morphology, and molecular characteristics of a new CPV isolate from the mosquito Uranotaenia sapphirina (UsCPV). The data generated demonstrate that UsCPV has a distinct electropherotype and represents a new Cypovirus species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The details on the field collections, larval examination, laboratory bioassays, and ultrastructural studies of UsCPV have been published elsewhere (25).

Cation assays.

Larvae were exposed to UsCPV in deionized water containing 10 mM MgCl2 and/or 10 mM CaCl2 and 0.04% alfalfa-pig chow (2:1) for food. Groups of 100 four-day-old colonized Aedes aegypti larvae were exposed to 10 larval equivalents (LE) of UsCPV with food and then examined after 3 days under a dissecting microscope against a dark background for patency (visible signs of infection). Nonpatent larvae were returned to the exposure media and reexamined the following day. Controls included exposure of larvae to 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, or virus alone.

Host range studies.

Mosquito larvae from laboratory colonies of Aedes aegypti, Anopheles albimanus, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Culex quinquefasciatus, and Ochlerotatus triseriatus were exposed to 10 LE of UsCPV in 10 mM MgCl2, and the ages ranged from 2 to 4 days old. Insects were examined 4 and 5 days later for signs of infection. Uranotaenia lowii were field collected and varied in age. They were exposed to 5 LE of UsCPV in 5 mM MgCl2.

To test the susceptibility of lepidopteran species, the 5-day-old larvae of Helicoverpa zea were exposed to a diet with 20 μl of Ludox purified UsCPV (see below). After 7 days, the larvae were homogenized, and a sample of the homogenate fed to 10 susceptible Aedes aegypti larvae in 10 ml of 10 mM MgCl2. The remainder of the suspension was layered on top of a Ludox gradient and spun at 16,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting bands were washed in deionized water and offered to susceptible Aedes aegypti larvae in the same manner.

Thirty patently infected Aedes aegypti larvae were reared to adulthood (4 to 5 days). Their guts were dissected, examined for signs of infection, and fed to healthy Aedes aegypti larvae (6).

Virus purification.

A total of 200 to 250 laboratory-infected Aedes aegypti larvae were homogenized and strained through 35-μm-pore-size mesh nylon cloth to remove large debris. The filtrate was purified by centrifugation on a 10-ml Ludox continuous gradient (26). The band of UsCPV, with an estimated density of 1.14 g/ml, was washed and stored in 0.1 mM NaOH (pH 10.0) at 4°C.

Electron microscopy and negative staining.

Guts of fourth-instar larvae were processed as described in reference 25. Drops of purified virus solution were negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7) for 30 s on Butvar-coated grids. The negatively stained samples were examined in a Hitachi H-600 electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

Electropherotype analysis.

Genomic dsRNA of UsCPV was extracted from purified polyhedra by using a QIAampViral minikit from Qiagen (13, 24). The RNA was precipitated, washed with 75% ethanol, dried under a vacuum, and resuspended in RNase-free water. Approximately 50 ng of genomic RNA was analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) in 1× TAE buffer by using a long gel box (Amersham model Arizon 24-20) at 60 V (constant voltage) for 16 h. Ethidium bromide was incorporated into the gel at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Preparations of genomic RNA from Bombyx mori cypovirus 1 (BmCPV-1) and Trichoplusia ni cypovirus 15 (TnCPV-15) were used for RNA profile comparisons and to provide electrophoretic markers for size estimation. The genomes of both BmCPV-1 and TnCPV-15 have been completely sequenced, and the sequence data are available from GenBank.

cDNA synthesis and amplification by PCR.

Approximate 500 ng of dsRNAs were ligated to a single-stranded anchor-primer, p-GAC CTC TGA GGA TTC TAA AC/iSp9/T CCA GTT TAG AAT CC-OH (iSp9 is a C9 spacer) by T4 RNA ligase in a 10-μl reaction containing 1× buffer and 10 U of ligase (New England Biolabs). The ligation reaction was incubated at 10°C for 12 h, and the products were precipitated at room temperature by using PelletPaint (Novagen). After the addition of 11 μl of water to the pellet, the tube was boiled for 4 min to denature the dsRNA and the first strand cDNA was synthesized by using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) at 37°C for 1 h. PCR was subsequently performed with the Advantage 2 PCR Kit (Clontech) with a single primer, GAGGGATCCAGTTTAGAATCCTCAGAGGTC, under the following conditions for 30 cycles: denaturing at 95°C for 30 s and annealing and extension at 68°C for 3 min.

Cloning and sequencing.

PCR products from UsCPV dsRNA were separated by 1% AGE. This PCR method normally produces DNAs that duplicate the number and size pattern of the dsRNA genome segments (23). Genome Seg-10 is ∼900 bp, and the appropriate DNA band was excised and purified by using the GeneClean glass bead method (Bio 101). The Advantage 2 PCR System contains a small amount of proofreading enzyme (∼2.5 to 5%, while the rest is Taq), but the PCR products from Advantage 2 PCR System can be cloned into a T vector without use of an A-tailing reaction. To increase the efficiency of ligation to a T vector, the purified DNAs were A tailed by using Taq at 70°C for 10 min in a reaction containing 200 nM dATP in place of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The tailing reaction products were purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by ligation to pGEM-T Easy vector.

The cloned insert from Seg-10 was amplified by PCR with SP6 and T7 primer pairs, and its identity was confirmed by the length of the PCR product and restriction mapping. Three clones for Seg-10 were partially sequenced by using SP6 and T7 primers, with a dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit, using a Beckman CEQ8000 system. The sequences obtained were used to design primers for direct sequencing of the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) products from Seg-10 (without cloning), confirming the original sequence data.

Homology searches and alignments.

BLASTX was used to search for similarities to the complete sequence of UsCPV Seg-10. The deduced protein sequences of all polyhedrin genes that were available from GenBank (accession numbers are shown in Fig. 9) were aligned with the UsCPV polyhedron sequence, and CLUSTAL W online software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/index.html) was used to construct a phylogenetic tree.

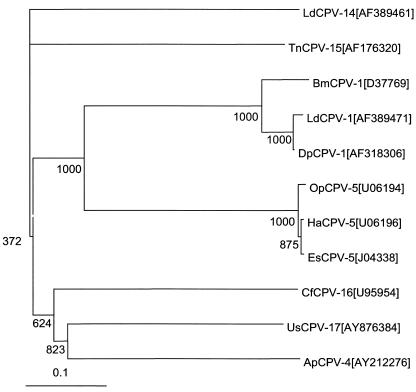

FIG. 9.

Phylogram of the gene nucleotide sequences from 10 CPVs, showing the genetic distance of UsCPV-17 to others. The letter and number following the CPV name is the polyhedrin sequence and accession number from the DNA databases.

Electrophoretic analysis of UsCPV proteins.

Purified UsCPV was denatured by boiling in protein sample buffer and analyzed by standard sodium dodecyl sulfate-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-12% PAGE).

RESULTS

Field collection.

Shapiro et al. (25) reported data concerning the collection of UsCPV-infected insects from a field site during 2001 to 2002. Eleven of sixteen collections made from the same site during 2003 contained infected insects. In 2003, infections were detected in July, earlier than in previous years (October). UsCPV-infected Anopheles crucians insects were collected (1 of 120 [0.8%]) during February, and infected Culex erraticus insects were isolated during August (3 of 111 [2.7%]). Uranotaenia sapphirina field infections ranged from 0.5% in July to 3.7% in September and averaged 1.7% ± 0.3% (n = 11) in 2003. No infected larvae were found in December.

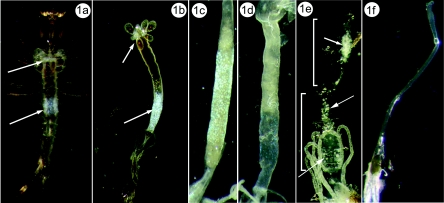

Gross pathology.

Virus infection did not noticeably affect the development, feeding, or behavior of the infected larvae. Patently infected UsCPV larvae have localized clusters of tightly packed inclusion bodies that appear as iridescent blue-white areas in their gastric ceca and posterior midgut cells (Fig. 1a to d). Patent infections in Aedes aegypti developed 4 to 5 days postexposure. There was very little (2%) virus-induced mortality in exposed larvae, and infected individuals pupated and emerged to the adult stage. Some of the individuals that survived to adulthood retained cypoviral infection in the midgut. Of 13 adults that emerged within 5 days from the laboratory infected Aedes aegypti larvae, 4 showed infection in both anterior and posterior midgut regions (Fig. 1e). Gross symptoms of infection (white areas with light blue iridescence) were more subtle than in infected larvae. The remaining nine adults showed no obvious signs of infection, but when they were fed to healthy larvae, three of them induced typical UsCPV infection. Therefore, 7 of 13 adults carried the UsCPV infection.

FIG. 1.

(a) Gross pathology of the ventral side of a fourth instar Uranotaenia sapphirina larva infected with UsCPV. Note the iridescent blue areas of virus accumulation in the posterior midgut and gastic ceca (arrows). (b) Dissected midgut from a fourth-instar UsCPV-infected Uranotaenia sapphirina larva with iridescent blue areas of virus accumulation in the posterior midgut and gastic ceca (arrows). (c) Dissected midgut from a fourth-instar UsCPV-infected (laboratory transmission) Aedes aegypti larva. Note the iridescent blue areas of virus accumulation in posterior midgut. (d) Dissected midgut of a healthy Aedes aegypti larva. (e) Dissected midgut from a UsCPV-infected (laboratory transmission) Aedes aegypti adult. Arrows point to the areas of UsCPV infection in anterior (upper bracket) and posterior midgut (lower bracket). (f) Dissected midgut from a healthy Aedes aegypti adult.

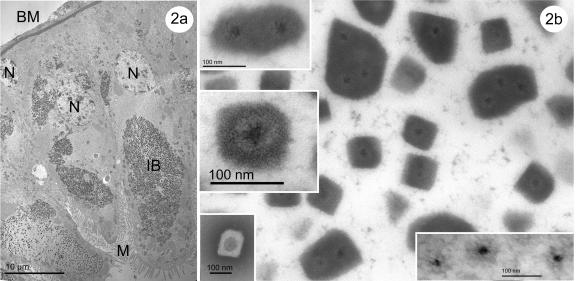

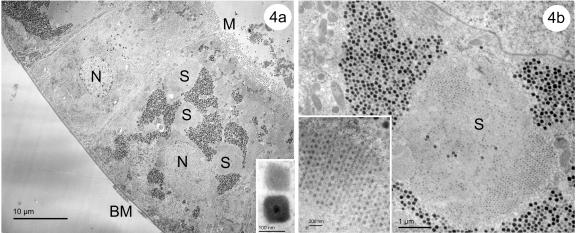

Ultrastructural studies.

Examination of larval midgut tissues by electron microscopy revealed viral infection in the cytoplasm of epithelial cells from the gastric ceca and posterior stomach (Fig. 2 to 5). There was no evidence of virus particles or polyhedra in the nuclei. Viral particles were localized in regions of the cytoplasm that were tightly packed with inclusion bodies and lacked typical cytoplasmic organelles and ribosomes (Fig. 2b). In some of the epithelial cells, these cypovirus areas occupied more than two-thirds of the cytoplasm, although other regions of even heavily infected cells looked unchanged, containing all of the normal cellular organelles.

FIG. 2.

(a and b) Transmission electron micrographs of UsCPV infections in the epithelial cells of posterior midguts in a field collected Uranotaenia sapphirina larva. (a) Large localized regions of the cytoplasm are tightly packed with inclusion bodies and lack typical cytoplasmic organelles. Upper and middle left insets in panel b show the ultrastucture of occluded virions. Note the crystalline structure of the polyhedra. The lower left inset shows a negatively stained occluded virion. The right inset shows ultrastructure of nonocluded virions. N, nucleus; IB. inclusion bodies; M, microvilli; BM, basal membrane.

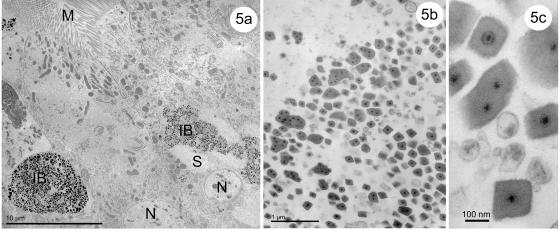

FIG. 5.

(a to c) Transmission electron micrographs of a cypoviral infection in the epithelial cells of posterior midgut of an Anopheles crucians larva collected in the same collection site as UsCPV-infected Uranotaenia sapphirina larva. (a) Healthy cells lay next to infected cells. (b) Inclusions with multiple virions are large and have an irregular shape. (c) Enlarged view of the inclusions. N, nucleus; IB, inclusion bodies; M, microvilli; S, stroma.

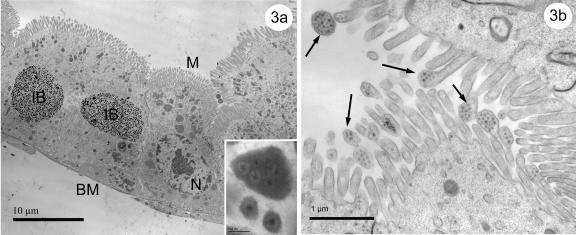

Regions of virogenic stroma also lacked the typical cytoplasmic organelles. Virus particles in the virogenic stroma were randomly distributed, while some were arranged in parallel rows (Fig. 4b). The nonoccluded virus particles (55 to 65 nm in diameter) are icosahedral in shape with a poorly defined capsid and an electron-dense core (darker than ribosomes and virogenic stroma) of ca. 20 to 25 nm in diameter (Fig. 2b, right inset). Virions were mostly occluded singly by the deposition of a crystalline polyhedrin matrix around individual particles, although small areas of multiply occluded virus (typically two to eight virions per polyhedron) were observed in cross sections (Fig. 2b). Polyhedra with a single virion measured 100 nm across. They had a distinct crystalline cubic lattice (Fig. 2b) typical of polyhedrin protein (21). Both nonoccluded and occluded viral particles lack membranes. Virions within the inclusion bodies consisted of an electron-dense core, measuring ∼25 nm in diameter) surrounded by a single capsid layer (ranging from 35 to 45 nm in diameter) with projections (10 to 15 nm long) that are typical of the spiked members of the Reoviridae, including other cypoviruses (20). An electron-transparent area (∼60 nm in diameter) was observed between the capsid and the polyhedron protein matrix (Fig. 2b, middle left inset), suggesting that there might be some modification of the polyhedrin matrix in the immediate vicinity of the occluded virion.

FIG. 4.

(a and b) Transmission electron micrographs of UsCPV infection in the epithelial cells of the posterior midgut of a Culex erraticus larva collected in the same collection site as UsCPV-infected Uranotaenia sapphirina larva. (a) The cell on the right is heavily infected, with more than half of the cytoplasm occupied by the UsCPV infection. Note several areas of virogenic stroma (S). The inset shows cuboidal singly occluded virions. (b) An area of virogenic stroma with parallel rows of nonoccluded virions. The inset shows an enlarged view of the parallel arrangement. N, nucleus; M, microvilli; BM, basal membrane.

Laboratory-transmitted UsCPV infections in different hosts (Uranotaenia lowii and Culex quinquefasciatus [Fig. 3]) collected at the same field site (Culex erraticus [Fig. 4]) exhibited a similar development and morphology. Natural cypoviral infections of Anopheles crucians larvae collected at the same field site exhibited slight morphological differences from those of other CPV-infected mosquitoes collected at the same site. Some of the inclusion bodies were large (up to 700 nm) and irregular in shape, containing more than six virions (up to eleven) in cross section (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 3.

(a and b) Transmission electron micrographs of UsCPV infection (laboratory transmission) in the epithelial cells of posterior midgut of a Culex quinquefasciatus larva. (a) A UsCPV-infected cell (on the left) lays next to a healthy cell (on the right). Similar size and shape of these inclusion body clusters and nuclei makes it difficult to distinguish between cypoviral and nucleopolyhedroviral infections at the light level. The inset shows round inclusions with one virion and an inclusion with eight virions. (b) Accumulation of nonoccluded virions in the microvilli (arrows). N, nucleus; IB, inclusion bodies; M, microvilli; BM, basal membrane.

Nonoccluded virions were found to accumulate in the microvilli of midgut epithelial cells of both larvae and adults (Fig. 3b and 6b). Although polyhedra containing multiple virions were infrequently observed in the larvae, approximately equal numbers of polyhedra containing single or multiple virions were observed in adult tissues. Adults also contained the largest inclusion bodies (containing up to 10 virions per cross section [Fig. 6a]), possibly reflecting an older infection that allowed the smaller polyhedra to fuse.

FIG. 6.

(a and b). Transmission electron micrographs of a cypoviral infection in the midgut epithelial cells of an UsCPV-infected (laboratory transmission) Aedes aegypti adult. (a) Large inclusion bodies contain up to 10 virions (on a cross section). (b) Accumulation of nonoccluded virions in microvilli (arrow). IB, inclusion bodies.

Virus host range.

UsCPV was experimentally transmitted to several other host species, including Culex quinquefasciatus (9.3% ± 6.1%, n = 5), Aedes aegypti (40.0% ± 2.8%, n = 64), Ochlerotatus triseriatus (1% ± 2.8%, n = 2), and Anopheles albimanus (3.9% ± 2.8%, n = 9). However, the virus did exhibit some host specificity since it could not be transmitted to larvae of either Anopheles quadrimaculatus or Helicoverpa zea. Culex erraticus, Uranotaenia lowii, and Anopheles crucians may also act as hosts for UsCPV since they were found together with infected Uranotaenia sapphirina in the field and exhibited similar infection characteristics, including the iridescent color.

Cations assays.

Although UsCPV in deionized water was noninfectious for Aedes aegypti larvae, the infection rate was significantly increased (to 34%) by the addition of 10 mM Mg2+ ions (Table 1). However, the addition of 10 mM Ca2+ ions to this mixture inhibited infection (to 0.7%).

TABLE 1.

Infection rate of UsCPV in Aedes aegypti exposed as 4-day-old larvae (third instar) and examined 3 days postinoculationa

| CaCl2 concn and UsCPV | Infection rate (%) ± SE with:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| No added MgCl2 | 10 mM MgCl2 | |

| 0 mM | ||

| 0 LE | 0 | 0 |

| 10 LE | 0 | 34.1 ± 4.4 |

| 10 mM | ||

| 0 LE | 0 | 0 |

| 10 LE | 0 | 0.7 ± 0.4 |

The exposure medium had either 0 or 10 mM MgCl2 with or without 10 mM CaCl2 as indicated.

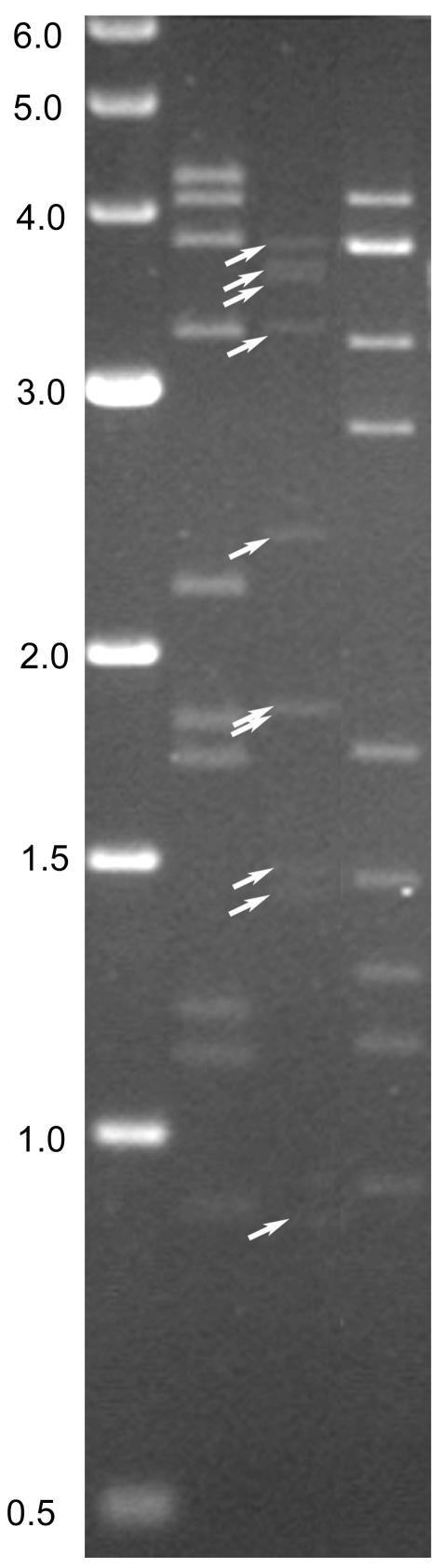

Electrophoretic analysis of UsCPV dsRNA.

CPV genome segments are packaged in exactly equal molar ratios (each virion contains one complete copy of the genome, and each segment is represented by the same number of molecules) (20). An initial analysis of the UsCPV genome by 1% AGE (using a 14-cm gel at 80 V for 4 h) generated seven RNA bands. However, three of the RNA bands were more intensely stained and appeared to contain two genome segments each (segments 2/3, 6/7, and 8/9, respectively). Analysis using longer 1% agarose gels (24 cm), a lower voltage (2.5 V/cm of gel with an average current of 19 mA), and a smaller RNA load, at 4°C, resolved each of the double bands into two single bands (Fig. 7). Based on previous sequence analyses of the genome segments of BmCPV-1 and TnCPV-15 (which were also separated on the same gel), the sizes of the UsCPV genome segments were estimated to be as follows: Seg-1, 3,900 bp; Seg-2, 3,700 bp; Seg-3, 3,600 bp; Seg-4, 3,300 bp; Seg-5, 2,400 bp; Seg-6, 1,900 bp; Seg-7, 1,900 bp; Seg-8, 1,500 bp; Seg-9, 1,500 bp; and Seg-10, 900 bp. Further comparison of genome segment molecular weights showed that UsCPV has an RNA electropherotype that is different from that of any other previously recognized Cypovirus species (types).

FIG. 7.

Electrophoretic separation (1% agarose gel) of the genome segments from three cypovirus isolates: 1 KB Marker (lane 1), TnCPV-15 (lane 2), UsCPV-17 (lane 3), and BmCPV-1 (lane 4). Note that the 11th segments of TnCPV-15 and BmCPV are not shown in this photo.

Sequence determination and analysis of segment 10.

Three clones derived from genome Seg-10 were partially sequenced from both ends by using primers SP6 and T7 on a Beckman CEQ8000 system. About 500 base calls were obtained, from which primers were designed, so that the entire genome segment could be sequenced from the RT-PCR product. The data derived from the RT-PCR product showed three A-to-G transitions (over the entire length) when compared to the sequence data from the cloned cDNA. The sequence of the RT-PCR product derived from UsCPV Seg-10 was 890 nucleotides long and contains an open reading frame from nucleotides 63 to 774 (accession number AY876384). The deduced protein has 237 amino acids with an estimated molecular mass of 27 kDa. Analysis by SDS-PAGE of the purified UsCPV showed several protein bands, including a major band with an apparent molecular mass very close to that predicted for the translation product from Seg-10 (27 kDa).

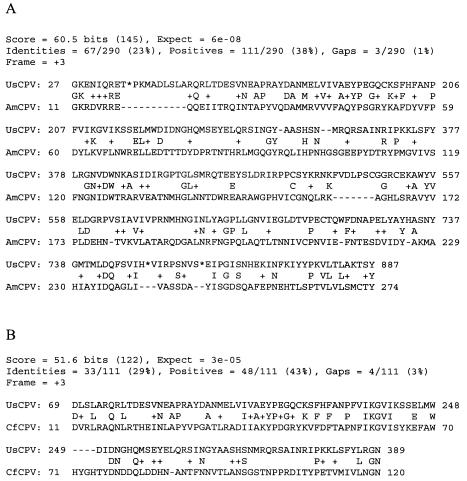

Homology searches and phylogenetic comparison with other CPV polyhedrins.

Nucleotide similarity searches using BLASTN found no significant matches to UsCPV Seg-10. However, BLASTX similarity searches for the deduced amino acid sequence found significant alignments to the polyhedrin genes from four Indian silkworm CPVs and the polyhedrin of UsCPV (Fig. 8). A phylogenetic tree was constructed, comparing all of the CPV polyhedrin gene sequences available from GenBank. The tree clearly demonstrates that UsCPV is only distantly related to any of the other CPVs previously characterized (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

BLASTX results for deduced amino acids of UsCPV Seg-10. (A) Alignment of UsCPV to Antheraea mylitta cypovirus (AmCPV-4). (B). Alignment of UsCPV to Choristoneura fumiferata cypovirus 16 (CfCPV-16).

Comparison of conserved RNA termini.

The conserved sequences found at the terminal regions of genome segments from members of the family Reoviridae represent one of the parameters that can be used to identify and distinguish different virus species (19). The terminal regions of the UsCPV Seg-10 are 5′-AGAACUU…GUUACACU-3′. These are different from those of the seven other cypovirus species (types 1, 2, 4, 5, 14, 15, and 16), for which sequence data have already been published (20).

DISCUSSION

Within the family Reoviridae, the prime determinant for inclusion of virus isolates within a single virus species is the ability to exchange genetic information by reassortment of genome segments during coinfection, thereby generating viable progeny virus strains (19, 20). However, the absence of effective tissue culture systems for most cypoviruses means that there is little direct evidence concerning genome segment reassortment between different isolates. The identification of Cypovirus species is therefore based primarily on an analysis of the virus genome, demonstrating either a distinctive dsRNA electropherotype pattern (as originally suggested by Payne and Rivers [22]), or more recently by a comparison of the RNA sequences (e.g., by comparison of the polyhedrin gene-genome segment 10) (20). Most of the cypoviruses previously characterized contain 10 dsRNA genome segments (Seg-1 to Seg-10) named in order of decreasing size (20), although an 11th segment (Seg-11) has been reported in some cases (4, 24). Currently, there are 16 CPV species (all from lepidopteran hosts) that have been characterized by their dsRNA electropherotype patterns on a 1% agarose or a 3 to 5% polyacrylamide gel (20). Molecular biology techniques (cross-hybridization analyses of the dsRNA, serological comparisons of CPV proteins, comparison of RNA sequences, and conserved terminal regions, among isolates in the same species) have confirmed the validity of these classifications (20).

Genomic data were not previously available for the putative cypoviruses from mosquitoes (12), and they have therefore remained “unassigned” to any specific Cypovirus species. With this report, the relationship of UsCPV to other cypoviral species has been established. Comparisons to BmCPV-1 and TnCPV-15 clearly show that the 10 segmented dsRNA genome of UsCPV has a different migration pattern (electropherotype). This analysis has also made it possible to calculate the molecular weights of the individual genome segments of UsCPV, confirming that their size distribution is different from that of all previously characterized cypoviruses. The near-terminal regions of UsCPV Seg-10 do not contain the conserved sequences identified in other cypoviruses (www.iah.bbsrc.ac.uk/dsRNA_virus_proteins/CPV-RNA-Termin.htm). These data indicate that, based on the species parameters published by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (20), UsCPV belongs to a distinct species, which we can now identify as cypovirus 17 (strain UsCPV-17).

The smallest segment (Seg-10) of UsCPV-17 encodes the viral polyhedrin, which has an estimated molecular mass of 27 kDa, that is relatively small among the polyhedrin proteins of previously characterized cypoviruses (estimated sizes between 25 and 37 kDa) (20). The polyhedrin amino acid sequence is unique compared to the equivalent protein of other cypoviruses (20), confirming that UsCPV-17 is a member of a distinct virus species (10).

The differences between UsCPV-17 and other CPVs may reflect a long evolutionary separation between viruses from distantly related orders of insects. Another important consideration is that mosquito larvae are aquatic organisms, whereas all previously characterized CPVs are from terrestrial lepidopteran hosts. Environmental and physiological differences between terrestrial and aquatic hosts may be reflected in the development and characteristics of their pathogens. Additional sequence data for the other genome segments of UsCPV-17 and other CPV species from mosquitoes should provide further clarification as to its position within the genus and relationships to other Cypovirus species.

UsCPV-17 has several characteristic features that are shared by the other CPVs reported from mosquitoes (2, 12). Virus infection is chronic and confined to the cytoplasm of epithelial cells of the gastric ceca and posterior stomach. Virions are icosahedral in shape, consisting of a central core surrounded by a spiked capsid, with cuboidal inclusion bodies that typically contain only one virion. Virus replication and assembly occur in the host cell cytoplasm and are accompanied by the formation of virogenic stroma. The production of very large numbers of inclusion bodies during UsCPV-17 infections gives the gut a distinctive blue iridescence due to the arrangement of virions and inclusion bodies into paracrystalline arrays. Iridescence in UsCPV-17-infected individuals is exhibited with various intensities and is a diagnostic characteristic for this virus that has not been reported for other CPVs.

In general, the development of UsCPV-17 appears to be similar to that of other mosquito cypoviruses. The virus is assembled within virogenic stroma and occluded singly (occasionally multiply) by the deposition of a crystalline polyhedrin matrix around individual particles. The polyhedrin protein appears to be arranged as a face-centered crystalline lattice. Although a similar process for the formation of polyhedra has been reported in Anopheles quadrimaculatus (3), it is different from that observed in other mosquitoes. In Culex restuans (2) polyhedra are also formed by deposition of polyhedrin around individual particles, although these subsequently coalesce to form larger pleomorphic inclusion bodies. In Ochlerotatus cantator (1) and Ochlerotatus taeniorhynchus (11) relatively large inclusion bodies are formed in clusters by deposition of protein around groups of virions. Thus, the majority of inclusion bodies in these mosquitoes are large, irregularly shaped and contain multiple virions. In contrast, the great majority of UsCPV-17 polyhedra (and the virus reported in Anopheles quadrimaculatus by Anthony et al. [3]) contain only one virion and have a relatively regular cuboidal shape.

Oral transmission of UsCPV-17 to mosquito larvae was enhanced by magnesium and inhibited by calcium ions. Mediation of transmission by divalent cations is well established for the mosquito baculoviruses CuniNPV and UrsaNPV (5, 25), although the role that these divalent ions play in either enhancing or inhibiting transmission is unknown. Treatment of virus particles from some other members of the Reoviridae, with divalent cations, or chelating agents, can lead to uncoating of the virus core (which is comparable to the cypovirus virion) (19). Since the outer capsid is involved in cell attachment and penetration during initiation of infection, this inevitably results in significant changes in infectivity. Although divalent metal ions could cause other conformational changes in the cypovirus capsid, it is interesting that two such distantly related virus groups (NPV and CPV) have similar transmission requirements, suggesting that perhaps the divalent ions interact with components of the mosquito midgut rather than directly with the virus particles.

UsCPV-17 has a relatively broad host range, including Culex quinquefasciatus, Aedes aegypti, Ochlerotatus triseriatus, Uranotaenia lowii, and Anopheles albimanus, although it was not transmitted to Anopheles quadrimaculatus or the lepidopteran host Helicoverpa zea. Previous per os transmission studies with mosquito CPVs were successful and also exhibited a certain degree of specificity (2, 8, 9). This indicates that there may be a number of distinct mosquito CPVs, of which several can infect the same mosquito host species.

The mechanism for the spread of mosquito CPVs within the individual insect is unknown. Nonoccluded virions of UsCPV-17 which accumulate in the microvilli in both adults and larvae might be involved in lateral transmission within the midgut. Nonoccluded virions of a CPV from Ochlerotatus cantator were also found to accumulate in microvilli of the larval midgut (1). Release of these virions into the ectoperitrophic space that was followed by attachment and cell entry would provide a mechanism for rapid spread to establish infections in other midgut cells.

Andreadis (1) noted that mosquito CPVs could be divided into two groups based on the morphology of their inclusion bodies. One group, characterized by small (156 nm) cuboidal polyhedral inclusions bodies containing a single virion, has previously only been isolated from anopheline mosquitoes (3, 7). The other group contains viruses from culicine mosquitoes, which have inclusion bodies that contain several viral particles and vary widely in size and shape (0.1 to 10 μm in diameter, irregular or spherical) (8, 9, 11). UsCPV-17 clearly falls within the former group, indicating that its members may not be restricted to a particular tribe of mosquitoes. Further biochemical and biophysical characterization of other cypovirus isolates from mosquitoes, with either large inclusion bodies (containing several virions) or small (single) polyhedra, will help to determine both their genetic relationships and species diversity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical support of Heather Furlong (USDA/ARS, Gainesville, Fla.).

S.R. and P.P.C.M. were supported by EU ReoID contract QLK2-CT-2000-00143.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreadis, T. G. 1981. A new cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus from the salt-marsh mosquito, Aedes cantator (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 37:160-167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreadis, T. G. 1986. Characterization of a cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus affecting the mosquito Culex restuans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 47:194-202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony, D. W., E. I. Hazard, and S. W. Crosby. 1973. A virus disease in Anopheles quadrimaculatus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 22:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arella, M., C. Lavalle, S. Belloncik, and Y. Furuichi. 1988. Molecular cloning and characterization of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus polyhedron and a viable deletion mutant gene. J. Virol. 62:211-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becnel, J. J., S. E. White, B. A. Moser, T. Fukuda, M. J. Rotstein, A. H. Undeen, and A. Cockburn. 2001. Epizootiology and transmission of a newly discovered baculovirus from the mosquito Culex nigripalpus and C. quinquefasciatus. J. Gen. Virol. 82:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becnel, J. J., S. E. White, and A. M. Shapiro. 2003. Culex nigripalpus (CuniNPV) infections in adult mosquitoes and possible mechanism for dispersal. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 83:181-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird, R. G., C. C. Draper, and D. S. Ellis. 1972. A cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus in the midgut cells of Anopheles stephensi and in the sporogonic stages in the Plasmodium berghei yoelii. Bull. W. H. O. 46:337-343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, T. B., H. C. Chapman, and T. Fukuda. 1969. Nuclear-polyhedrosis and cytoplasmic-polyhedrosis virus infections in Louisiana mosquitoes. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 14:284-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark, T. B., and T. Fukuda. 1971. Field and laboratory observations of two viral diseases in Aedes sollicitans (Walker) in southeastern Louisiana. Mosquito News 31:193-199. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Echeverry, F., J. Bergeron, W. Kaupp, C. Guertin, and M. Arella. 1997. Sequence analysis and expression of the polyhedrin gene of Choristoneura fumiferana cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CfCPV). Gene 198:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federici, B. A. 1973. Preliminary studies of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus of Aedes taeniorhynchus. Fifth Int. Colloq. Insect Pathol. Microbiol. Contr. 1:34-41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federici, B. A. 1985. Viral pathogens of mosquito larvae. Bull. Am. Mosquito Control Assoc. 6:62-74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagiwara, K., S. Rao, W. Scott, and G. R. Carner. 2002. Nucleotide sequences of segments 1, 3, and 4 of the genome of Bombyx mori cypovirus 1 encoding putative capsid proteins VP1, VP3, and VP4, respectively. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1477-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes, I. 1991. Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Fifth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch. Virol. 1991(Suppl. 2):186-205. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hukuhara, T., and J. R. Bohami. 1991. Reoviridae, p. 394-430. In J. R. Adams and J. R. Bohami (ed.), Atlas of invertebrates. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 16.Ishimori, N. 1934. Contribution a l'etude de la Grasserie du ver a soie. C. R. Seances Soc. Biol. Fil. 116:1169-1174. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertens, P. P. C., S. Pedley, N. E. Crook, R. Rubinstein, and C. C. Payne. 1999. A comparison of the genomic dsRNA segments of six cypovirus isolates by cross-hybridisation of their dsRNA genome segments. Arch. Virol. 144:561-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertens, P. P. C., N. E. Crook, R. Rubinstein, S. Pedley, and C. C. Payne. 1989. Cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus classification by electropherotype: validation by serological analyses and agarose gel electrophoresis. J. Gen. Virol. 70:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertens, P. P. C., R. Duncan, H. Attoui, and T. S. Dermody. 2004. Reoviridae, p. 447-454. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy: eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press, London, England.

- 20.Mertens, P. P. C., S. Rao, and H. Zhou. 2004. Cypovirus, p. 522-533. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy: eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press, London, England.

- 21.Payne, C. C., and P. P. C. Mertens. 1983. Cytoplasmic polyhedrosis viruses, p. 425-504. In W. K. Joklik (ed.), Reoviridae. Plenum Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 22.Payne, C. C., and C. F. Rivers. 1976. A provisional classification of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis viruses based on the sizes of the RNA genome segments. J. Gen. Virol. 33:71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, S. 2002. Characterization of a cypovirus from cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni) and development of systems for cypovirus demarcation. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Genetics and Biochemistry, Clemson University, Clemson, S.C.

- 24.Rao, S., G. R. Carner, S. W. Scott, T. Omura, and K. Hagiwara. 2003. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of cypoviruses in the family Reoviridae. Arch. Virol. 148:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro, A. M., J. J. Becnel, and S. E. White. 2004. A nucleopolyhedrovirus from Uranotaenia sapphirina (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 86:96-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Undeen, A. H., and N. E. Alger. 1971. A density gradient method for fractionating microsporidian spores. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 18:419-420. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xeros, N. 1952. Cytoplasmic polyhedral virus disease. Nature 170:1073-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]