Abstract

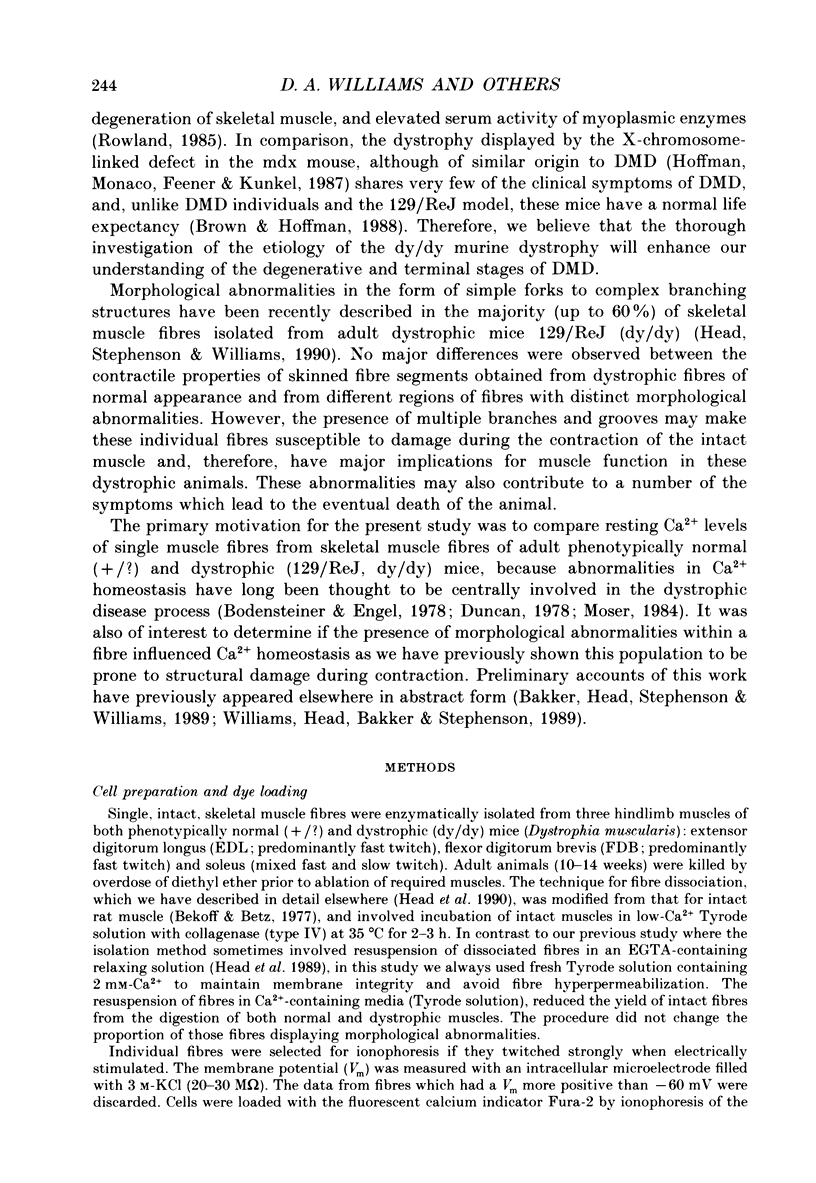

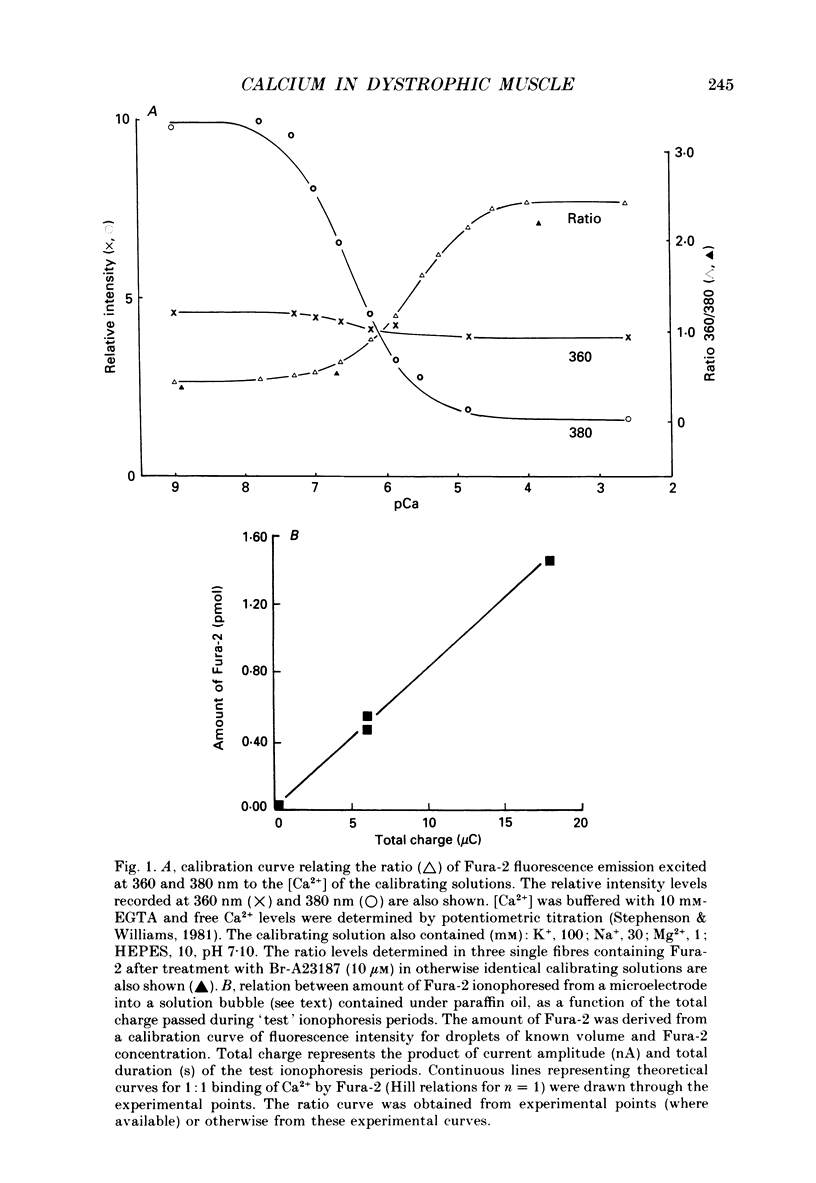

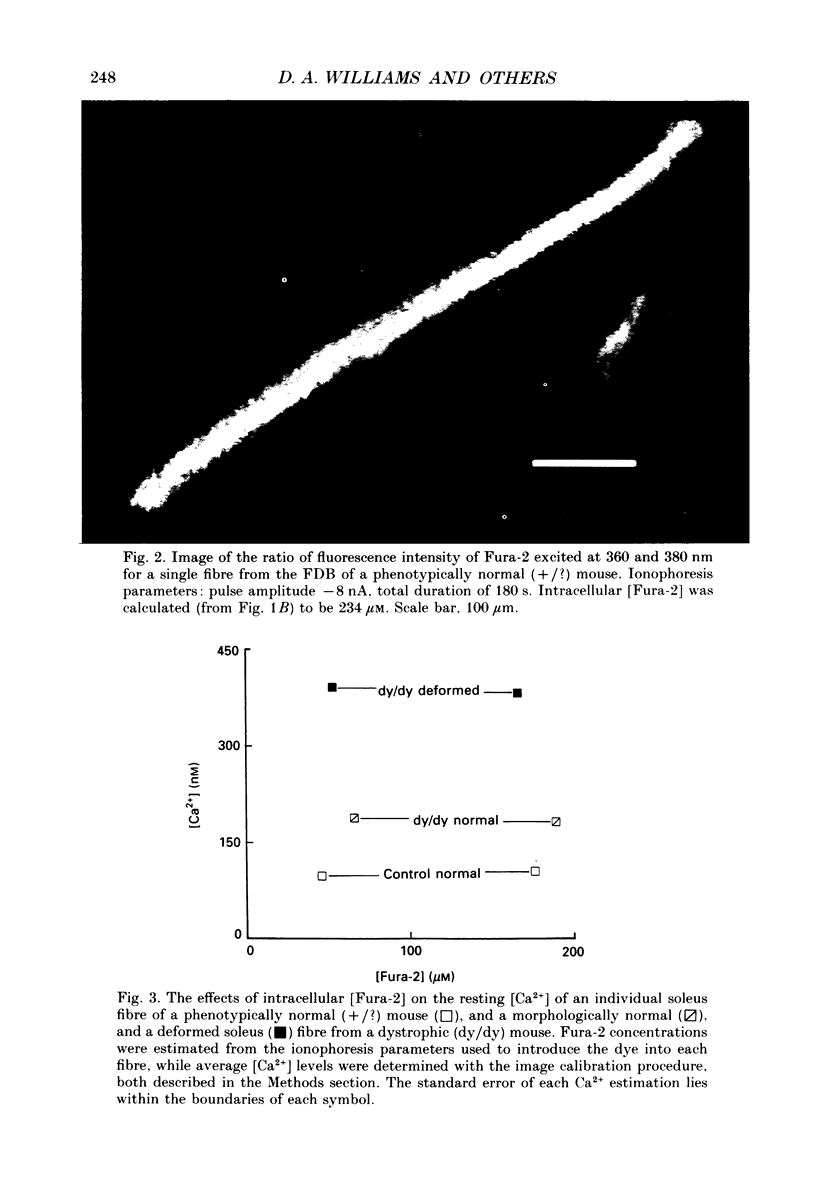

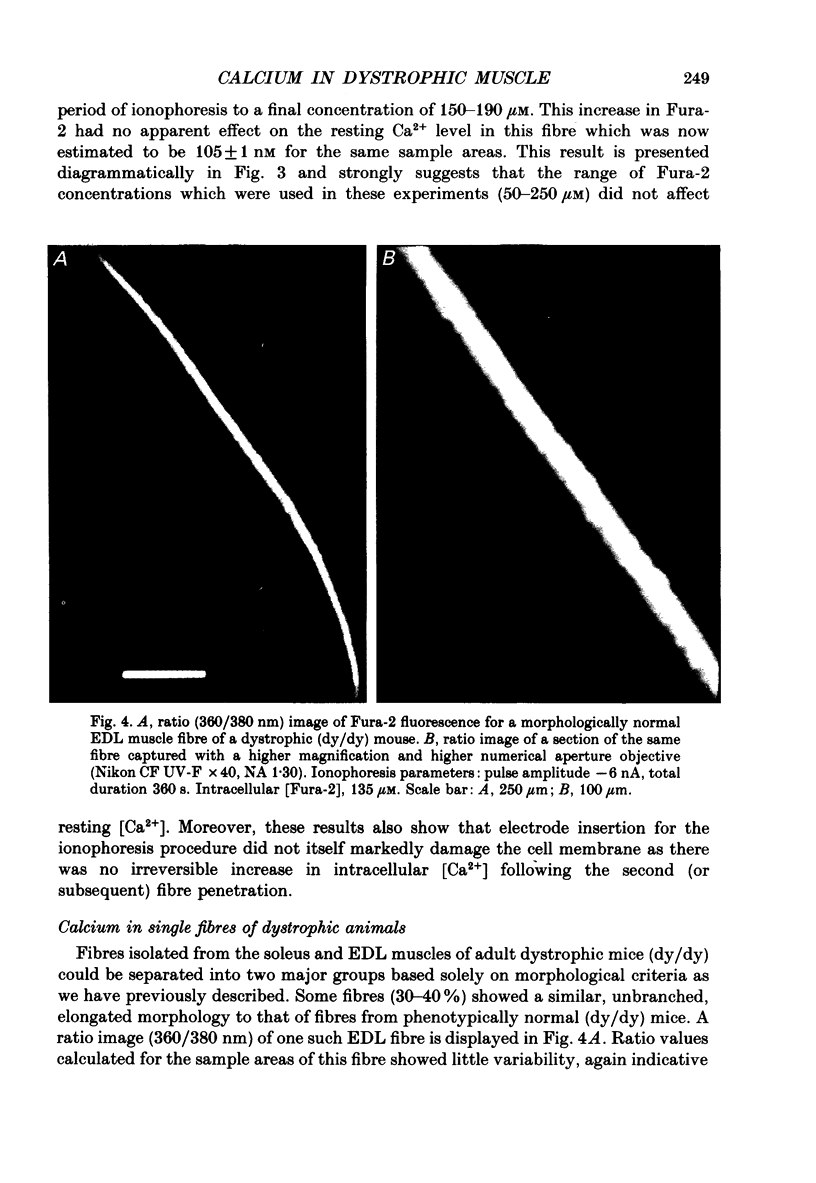

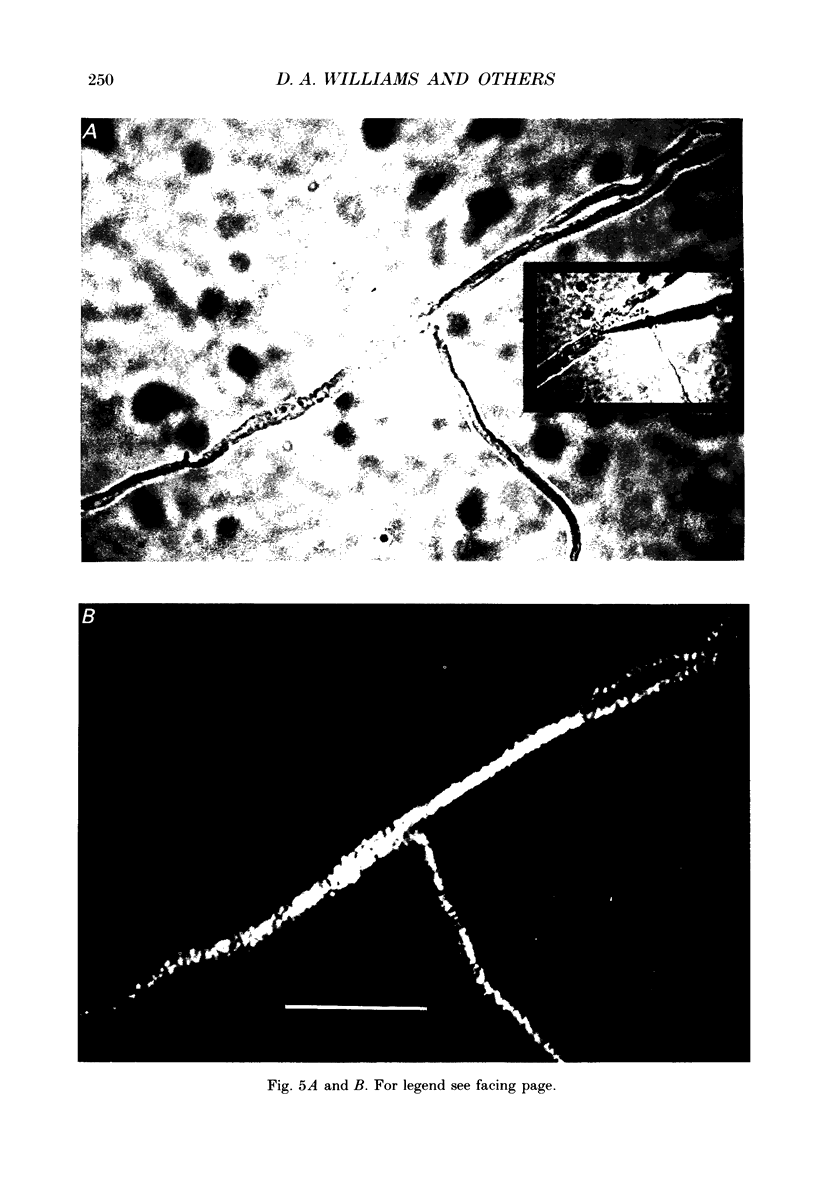

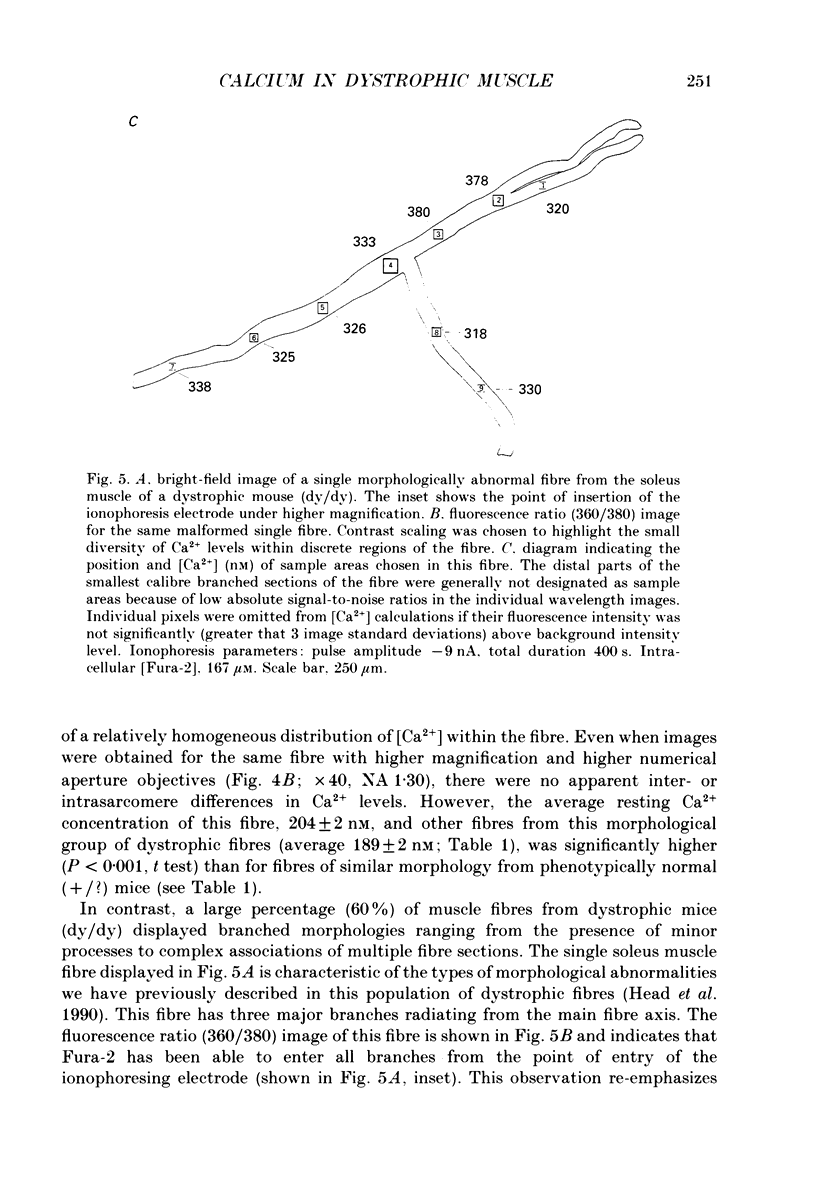

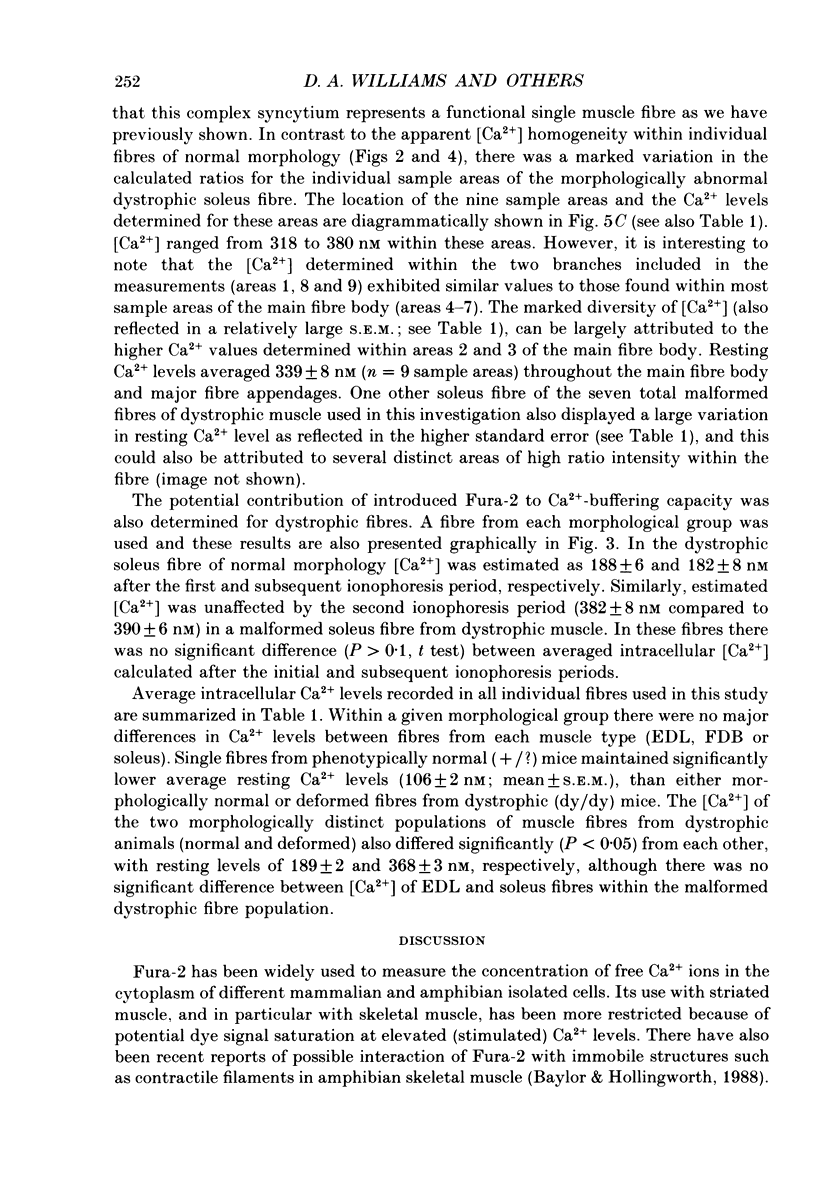

1. Single, intact muscle fibres were dissociated enzymatically from skeletal muscles of phenotypically normal (+/?) and dystrophic mice (129/ReJ dy/dy: Dystrophia muscularis), and resting Ca2+ levels were measured by image analysis of intracellular Fura-2 fluorescence in distinct parts of the fibres. 2. Fura-2 was introduced into fibres by ionophoresis with glass microelectrodes to concentrations of between 50 and 200 microM. Over this concentration range there was no apparent buffering of intracellular Ca2+ by Fura-2. 3. Fibres isolated from the soleus, flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of normal animals maintained resting [Ca2+] of 106 +/- 2 nM. Ca2+ distributions within individual fibres were homogeneous. 4. Fibres from dystrophic animals maintained [Ca2+] that was elevated two- to fourfold in comparison to normal fibres. 5. The population of skeletal fibres from dystrophic mice which displayed morphology similar to that of fibres of normal animals were found to have Ca2+ levels that averaged 189 +/- 2 nM. The distribution of Ca2+ within these fibres appeared uniform. 6. The population of dystrophic fibres that possessed morphological abnormalities maintained even higher Ca2+ concentrations (368 +/- 3 nM). Several fibres from this morphological group displayed obvious heterogeneity in Ca2+ distribution with distinct, localized areas of higher Ca2+. 7. These results support the contention that Ca2+ homeostasis is markedly impaired in dystrophic muscle. The elevated Ca2+ levels are near the threshold for contraction and, together with severe morphological fibre abnormalities, are probably centrally involved in fibre necrosis apparent in muscular dystrophy.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baylor S. M., Hollingworth S. Fura-2 calcium transients in frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1988 Sep;403:151–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekoff A., Betz W. J. Physiological properties of dissociated muscle fibres obtained from innervated and denervated adult rat muscle. J Physiol. 1977 Sep;271(1):25–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodensteiner J. B., Engel A. G. Intracellular calcium accumulation in Duchenne dystrophy and other myopathies: a study of 567,000 muscle fibers in 114 biopsies. Neurology. 1978 May;28(5):439–446. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. H., Jr, Hoffman E. P. Molecular biology of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Trends Neurosci. 1988 Nov;11(11):480–484. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C. J. Role of intracellular calcium in promoting muscle damage: a strategy for controlling the dystrophic condition. Experientia. 1978 Dec 15;34(12):1531–1535. doi: 10.1007/BF02034655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 25;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head S. I., Stephenson D. G., Williams D. A. Properties of enzymatically isolated skeletal fibres from mice with muscular dystrophy. J Physiol. 1990 Mar;422:351–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman E. P., Monaco A. P., Feener C. C., Kunkel L. M. Conservation of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene in mice and humans. Science. 1987 Oct 16;238(4825):347–350. doi: 10.1126/science.3659917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaizzo P. A., Seewald M., Oakes S. G., Lehmann-Horn F. The use of Fura-2 to estimate myoplasmic [Ca2+] in human skeletal muscle. Cell Calcium. 1989 Apr;10(3):151–158. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(89)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs E. R., Bradley W. G., Henderson G. Longitudinal fibre splitting in muscular dystrophy: a serial cinematographic study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973 Oct;36(5):813–819. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leberer E., Härtner K. T., Pette D. Postnatal development of Ca2+-sequestration by the sarcoplasmic reticulum of fast and slow muscles in normal and dystrophic mice. Eur J Biochem. 1988 Jun 1;174(2):247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-Heron B., Loirat M. J., Ollivier B., Leoty C. Calcium-related defects in cardiac and skeletal muscles of dystrophic mice. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1987;86(2):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J. R., Alamo L., Caputo C., Wikinski J., Ledezma D. Intracellular ionized calcium concentration in muscles from humans with malignant hyperthermia. Muscle Nerve. 1985 Jun;8(5):355–358. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongini T., Ghigo D., Doriguzzi C., Bussolino F., Pescarmona G., Pollo B., Schiffer D., Bosia A. Free cytoplasmic Ca++ at rest and after cholinergic stimulus is increased in cultured muscle cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Neurology. 1988 Mar;38(3):476–480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E. D., Becker P. L., Fogarty K. E., Williams D. A., Fay F. S. Ca2+ imaging in single living cells: theoretical and practical issues. Cell Calcium. 1990 Feb-Mar;11(2-3):157–179. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser H. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: pathogenetic aspects and genetic prevention. Hum Genet. 1984;66(1):17–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00275183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poenie M., Alderton J., Steinhardt R., Tsien R. Calcium rises abruptly and briefly throughout the cell at the onset of anaphase. Science. 1986 Aug 22;233(4766):886–889. doi: 10.1126/science.3755550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D. G., Williams D. A. Calcium-activated force responses in fast- and slow-twitch skinned muscle fibres of the rat at different temperatures. J Physiol. 1981 Aug;317:281–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. R., Westwood T., Regen C. M., Steinhardt R. A. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988 Oct 20;335(6192):735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. A., Fay F. S. Intracellular calibration of the fluorescent calcium indicator Fura-2. Cell Calcium. 1990 Feb-Mar;11(2-3):75–83. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. A., Fogarty K. E., Tsien R. Y., Fay F. S. Calcium gradients in single smooth muscle cells revealed by the digital imaging microscope using Fura-2. Nature. 1985 Dec 12;318(6046):558–561. doi: 10.1038/318558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]