Abstract

Background

Cancer became a chronic disease that could be managed at home. Homecare supported person-centred care, which was guided by the Picker Principles defining key elements for care delivery. The study aimed to explore and appraise the dimensions underlying cancer patients' and caregivers' experience and expectations with Home Cancer Care, adopting a person-centerd care framework.

Methods

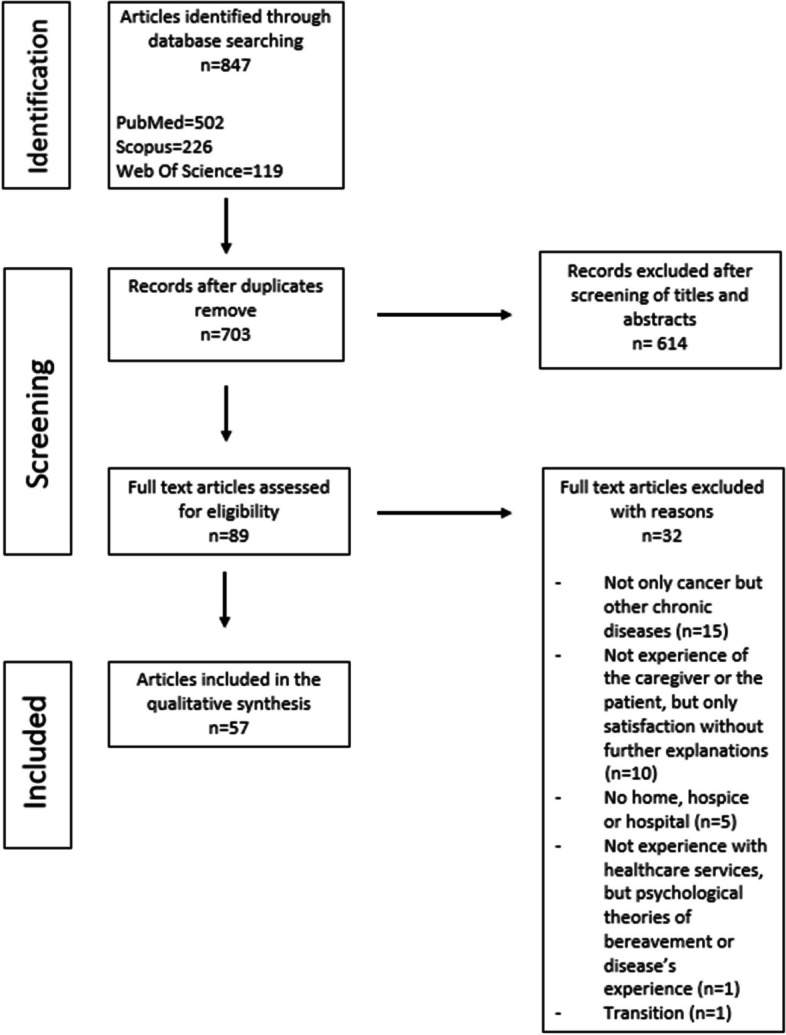

We carried out a scoping review of the literature using three databases, PubMed, Scopus, and WoS for a total of 703 articles. PRISMA guidelines were followed. 57 articles were included in the review. The extracted data were categorized according to the type of care (Palliative, Support, Therapeutic, Recovery after transplant, Rehabilitation), the target population (patients or caregivers), the study design, and the principles related to patients and caregivers’ experience, classified through the Picker framework.

Results

The most common type of care in the home setting was palliative care. According to the Picker Principles, most of the studies reported “Emotional support, empathy and respect,” followed by “Clear information, communication, and support for self-care,” as key consideration for both patients and caregivers. The findings from these studies indicate many positive experiences regarding treatments, services, and interactions with health professionals. Caregivers' needs were most frequently (29%) classified as relational and social. From the patient’s perspective, the most common needs fell under the category of “Health System And Information” (43%).

Conclusion

We could state that HCCs align with the PCC paradigm; however, careful attention is needed to ensure that the experience of both patients and caregivers remains positive. In our study, a strong need for psychological support does not emerge either for patients or caregivers, unlike previous studies in which psychological needs were among the most frequently cited. Given the growing role of technology in home care, a new category addressing the usefulness and ease of use of technology could be added to the person-centred framework.

Recent articles have highlighted the growing use of telemedicine in the home care setting as a support tool for self-care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-12058-w.

Keywords: Person centred care, Cancer care, Homecare services, Caregivers, Patient experience

Introduction

The two leading causes of mortality in Europe are circulatory diseases and cancer, which account for 35% and almost 26% of all deaths, respectively [1]. The European Society for Medical Oncology predicts a decrease in cancer mortality rates of 6% in men and 4% in women over the period 2017–2022 [2], while incidence [3] and prevalence of the disease are both expected to increase, along with enhanced detection and treatment options. Overall, there has been an increase in the number of patients surviving cancer that will rise in the future. In the United States the number of cancer survivors is projected to increase by 24.4%, to 22.5 million, by 2032 [4]. For many people, cancer survival currently means living with a chronic and complex condition [5, 6], often requiring long and frequent therapies affecting both physical and psychological aspects of patients’ and caregivers’ lives.

Improved survival and higher incidence lead to a significant rise in care costs and the need for assistance that burden both the healthcare systems and society [7]. During treatment and in the last phase of the disease, cancer patients often rely on family or friends for support [8]. Estimates report that about 70–80% of cancer care is managed by caregivers and family members in non-hospital settings [8]. The burden on caregivers has even increased during the Covid-19 emergency. Indeed, the pandemic caused a reduction in the institutional supply of non-acute care (hospitals, long-term care facilities) and most of the needs of cancer patients for systemic therapies, longer follow-up, and the last phase of the disease have been shifted to home or community level [9].

The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated an ongoing organisational process aimed at decentralizing part of the oncological services from hospital to community settings and home care [10]. Relocating healthcare is a debated issue and many countries are envisaging shifts towards home-based interventions for the treatment of less complex care and reinforcement of self-care and peer-support for chronic patients [11].

Home cancer care (HCC) comprises different types of home-based interventions such as end-of-life care for terminal cancer patients, nutritional interventions, exercise programs or physical activity, and chemotherapy [12].

This paper aims to explore and appraise the dimensions underlying cancer patients' and caregivers' experience and expectations with HCC adopting a person-centerd care framework. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines home healthcare as: “a system of care provided at the patient’s home to help avoid or delay the need for acute or long-term institutional interventions” [13]. HCC enables the development of cancer care models that are more flexible and personalised for the patient, also responding to the need for proximal care; moreover, the importance of user choice, control, and self-determination in the selection of healthcare settings is also arising, and home-based solutions are often preferred especially for the fragile, elderly, and people with terminal illness [14, 15]. Home care solutions have been widely supported because of the potential reduction in public expenditure, in addition to health, social, and emotional benefits. Indeed, home care seems to decrease the use of inappropriate care services (e.g. emergency department visits) and improve adherence to treatment; furthermore, home care enhances clinical outcomes as well as patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life and satisfaction [16–21].

In addition, home care supports Patient-Centred Care, especially by ensuring fast access to healthcare services and enabling greater involvement and collaboration of patient’s relatives and friends [22]. Patient-Centred Care has evolved into Person-Centred Care (PCC), which places persons at the centre, alongside their context, history, family, and individual strengths and weaknesses [23]. Individuals, families, and communities are served by and can participate in trusted healthcare systems that meet their needs in humane and holistic ways [23, 24]. PCC implies that the person, and not the disease, is the primary focus of carers [25]. It also means a shift from viewing the patient as a passive target of a healthcare system to another model, where the patient is an active part of his or her care and decision-making process [22]. Caregiver’s role is also key since family and informal caregivers bear most of the duties of home care support [26]. There are several frameworks in the literature analysing PCC [27–29], one of which is the Picker framework. The Picker Institute conducted extensive research starting in the late 1980s to better understand the patient experience and developed a framework to describe it. The framework, defined by eight principles, outlines essential elements for delivering high-quality care [30, 31]. We selected this framework for several reasons: [1] it has served as a conceptual foundation for published PCC studies in various healthcare contexts, [2] it was developed through focus groups and national interviews with multiple stakeholders, [3] it incorporates interpersonal aspects of care, and [4] emphasizes the multidimensionality of PCC through eight distinct and comprehensive dimensions [32]. Specifically, we carried out a scoping literature review aimed at addressing the following research questions: how can the evidence gained from assessing dimensions of patients’ and caregivers’ experience of HCC be synthesized? In the context of HCC, do patients’ and caregivers’ needs differ? Are HCC services developed within the framework of PCC?

Methods

A scoping literature review was performed by interrogating three databases: Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). The detailed research query can be found in an additional file [see Additional file 1].

A collection of search keywords was used to extract literature from the three databases, with an emphasis on (a) the disease (cancer); (b) the care setting (home); (c) patients’ and caregivers’ experience. The search was performed on titles and abstracts. The detailed search query for the databases can be found in the supplementary material.

The search was filtered for English-full text original research articles published in peer reviewed journals, while narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded.

The articles found were published between 1990 and 2022 and no articles were excluded based on year of publication. The literature search was conducted between August and September 2022.

Bibliometrix [33] was used to build one database, remove duplicates, and conduct further bibliometric analysis. After the exclusion of duplicates, the article titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (MFF). in case of doubts in the screening phase, the other members of the research team were also involved (FF; GB). The full texts were then screened and selected by three independent authors (MFF; FF; GB). Any discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until a consensus was reached. Follow-up searches (manual search) were conducted on citations found in eligible studies.

Records were screened for exclusion based on predefined criteria. Papers were excluded if: (a) did not focus on patient or caregiver experience but on the broader concept of satisfaction or reported outcomes (such as symptoms); (b) considered other illness rather than cancer or associated cancer with other chronic conditions or addressed paediatric patients; (c) the healthcare service was delivered in hospital or hospice setting, not at home or during the transition from hospital to home; (d) the article expressed the experience or opinion of healthcare professionals only; (e) the focus was on the description or evaluation of the home-based program without the experience of the patient/caregiver, or considered only psychological theories of bereavement as explanation for patient and caregiver experience. As this review provides an overview of evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias, no quality assessment was conducted, consistent with PRISMA-ScR guidelines [34], Supplementary material 3.

To analyse the articles, a grid was developed through a process of consensus among researchers. (FF, MFF; GB). The information extracted with the grid includes (Table 1) authors, title, study design, targeted population (patient, caregiver), year, type of home cancer care (therapeutic, palliative, rehabilitation), sample size, key elements of the experience, and findings of the intervention.

Table 1.

Analysis of the included paper

| Author | Country | Design of the study | Type of intervention | Target population (patients, caregiver) | N° of patients | N° of caregivers | N° of HCP | Type of cancer | Key elements of the experience | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aoun SM, Deas K, Howting D, Lee G. 2015 [35] | Australia | Mixed methods | Palliative care | Caregivers | 29 | primary brain cancer |

Opportunity to connect with nurses; Empowering caregivers; Reassurance and support |

The supportive intervention to caregivers delivered in a feasible and beneficial way. The data provide a base for the planning and coordination of support services for caregivers | ||

| Appelin G, Berterö C. 2004 [36] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 6 | undefined | Competent health professional; Sensitive health professional; Lack of knowledge; Control of symptoms | Importance of well-functioning teamwork for patients at home. Patients and their kin are part of the team | ||

| Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. 2009 [37] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 8 | undefined | To be dignified; Support | Soft massage helps patients to find inner peace | ||

| Bergkvist K, Fossum B, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Larsen J. 2017 [38] | Sweden | Qualitative | Recovery | Patients | 15 | haematological | To be in a safe place; To have a supportive network; Supportive network | Patients felt safe in both home and hospital setting. Supportive network was essential for in the care. Home care had positive advantages over hospital care | ||

| Bergkvist K, Larsen J, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Svahn BM. 2013 [18] | Sweden | Mixed-method | Recovery | Patients | 41 | haematological |

Person support; Self support; Self-relation support |

High satisfaction for patients at home. Importance of updated information and encouragement from the staff | ||

| Bergkvist K, Larsen J, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Fossum B. 2018 [39] | Sweden | Qualitative | Recovery | Caregivers | 14 | haematological | Support; Competence of the team; Feel safe; Freedom; No travel burden | Positive experience of home care. Nurses play a key role as support for family members to prevent uncertainty | ||

| Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Rodriguez C. 2010 [40] | Canada | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 12 |

Lack of formal support; Poor communication; Lack of coordination; Financial stress; Sensitivity and compassion |

Caregivers were challenged by the care and the absence of support. A person-cantered philosophy of care will best meet the needs of the patient and his or her family and caregivers | |||

| Capodanno I, Rocchi M, Prandi R, Pedroni C, Tamagnini E, Alfieri P, Merli F, Ghirotto L. 2020 [41] | Italy | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 17 | haematological |

Perceiving Home Care as an Opportunity; Feeling the Support from HPs |

Caregivers have needs as patients. Professionalism, humanity, and a prompt availability of the HPs in case of need are considered essential elements for the proper functioning of haematological home care. Patients satisfied with home care | ||

| Crisp N, Koop PM, King K, Duggleby W, Hunter KF. 2014 [17] | Canada | Qualitative | Therapeutic | Patients | 10 |

Chemotherapy in a “Natural Habitat”; Improved care provision and reception in the home setting |

Positive experience with home chemotherapy | |||

| Cronfalk BS, Strang P, Ternestedt BM, Friedrichsen M. 2009 [42] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 22 | Thoughtful attention | Massage as a source of support in palliative care. Personal dedication was important to all patients | |||

| Duggleby WD, Penz KL, Goodridge DM, Wilson DM, Leipert BD, Berry PH, Keall SR, Justice CJ. 2010 [43] | Canada | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers; Patients; Health care professional | 6 | 10 | 12 |

Lack of information Poor communication with health care providers Lack of accessibility to services |

Timely communication, information and supportive network facilitate the cancer journey | |

| Edbrooke L, Denehy L, Granger CL, Kapp S, Aranda S. 2020 [44] | Australia | Qualitative | Rehabilitation | Patients | 92 |

Improved care provision and reception in the home setting; Lack of acceptance; Lack of motivation; Thoughtful attention; Nurse ad a source of information; Support from program staff; Telephone follow up; Useful reminder; Partnership/co production |

Home rehabilitation well accepted by patients | |||

| Ferrell BR, Cohen MZ, Rhiner M, Rozek A. 1991 [45] | USA | Qualitative | Support | Caregivers | 85 | Lack of training for caregivers; Better communication; Honesty form professionals | Caregiver support and education important for home care | |||

| Ferrell BR, Taylor EJ, Grant M, Fowler M, Corbisiero RM. 1993 [46] | USA | Qualitative | Support | Patients; Caregivers; Health care professional | 10 | 10 | 10 | Encouraged; Availability of professionals; Knowledge | Caregivers seek to provide comfort and nurses attempt to eradicate pain | |

| Forbat L, Maguire R, McCann L, Illingworth N, Kearney N. 2009 [47] | UK | Qualitative | Support | Patients | 12 | breast, lung or colorectal cancer |

Communication; Access; Surveillance by the healthcare staff |

Technological innovations are welcomed by patients and can properly monitored patient symptoms | ||

| Friedrichsen M, Erichsen E. 2004 [48] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 11 |

Nurse's lack of control Not receiving attention from nurse |

Need of careful assessment of patients' symptoms by palliative care professionals | |||

| Friedrichsen M, Lindholm A, Milberg A. 2011 [49] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 45 |

Communication of truth Individuals' preferences |

Truth communication by health care professionals should be done according to the patient's preferences | |||

| Griffiths J, Ewing G, Rogers M. 2013 [50] | UK | Qualitative | Support | Caregivers; Patients | 58 | 10 | 9 |

Patient’s pain and condition Felt valued, reassured and supported |

Patients and carers confirmed that they felt valued, reassured and supported by district nurses | |

| Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D, Bridger S, Robinson V, George R, Beynon T, Higginson IJ. 2012 [51] | UK | Cross-sectional qualitative study | Palliative care | Caregivers | 20 |

Emotional support (need) To be visible (need) The need for illness specificity (lack of information) |

Caregivers need to be prepared for their new role, to be cast by providers as service recipients, to receive ongoing information relevant to the patient, to manage uncertainty, and to deliver appropriate information for earlier and late stage caregiving. This demands flexibility in the content of any intervention |

|||

| Hathiramani S, Pettengell R, Moir H, Younis A. 2019 [52] | UK | Qualitative | Rehabilitation | Patients | 35 | lymphoma |

Gave focus to recovery Good to track progress Took time Difficulties in participation Altruism Additional information |

Participating in a home-based programme following treatment was a positive experience and aided recovery to pre-morbid function in this sample of lymphoma survivors. Participants felt the programme provided the support they required. A large proportion reported they did not receive sufficient advice on completion of treatment | ||

| Hermosilla-Ávila AE, Sanhueza-Alvarado O, Chaparro-Díaz L. 2021 [53] | UK | Qualitative | Palliative care | Both | 17 | 17 |

Connection Availability Communication Integral or holistic needs Family needs Treatment needs Concern (by health professionals) Empathy and companionship |

The findings of this study support the view that both patients and caregivers expect to receive from the humanized nursing care service, beyond the search for solutions or decision making | ||

| Hjörleifsdóttir E, Einarsdóttir A, Óskarsson GK, Frímannsson GH. 2019 [54] | Iceland | Quantitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 70 |

Well-being and dignity Information and communication Respect for treatment preferences Emotional and spiritual support Management of symptoms Choice of facility Care around the time of death Access to hospice home care services Information provided from the hospice home care team about benefits after the patient’s death |

Findings in this study indicated the influential part of communication in end-of-life care showing that most of the participants (n = 70) evaluated various aspects of care related to communication as excellent. In this study, most of the participants (n = 66) were dissatisfied with the lack of warning before the patient’s death. Cooperation with patients themselves and informal carers has a role to play in policy-making for future end-of-life care | |||

| Howell D, Fitch M, Caldwell B. 2002 [55] | Canada | Qualitative | Support | Patients | 20 |

Sharing the journey Unburdening Taking time to address all needs Understanding the illness Providing a link to information and resources Stabilizing Unconvering the strenght to survive |

The findings of this study suggest that expert oncology nursing support provided in the home environment is perceived by people with cancer as having a significant impact on their experience of living with cancer | |||

| Hull MM. 1990 [56] | USA | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients; Caregivers; Relatives | 10 | 14 |

Set limits on caregiving roles Developing alternative sources of support (need) Open discussion Caregiver training |

Within the hospice philosophy, health care professionals have long addressed the family as the unit of care and are in a unique position to assist families as they care for dying relatives at home. Continuing to focus research on caregiving families has the potential for generating new knowledge about how hospice professionals can most effectively support families through one of life's most difficult experiences |

||

| Ishii Y, Miyashita M, Sato K, Ozawa T. 2012 [57] | Japan | Quantitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 306 |

Burden of care Balance of work and care Control of symptoms |

This study indicates that it is important for home care providers to introduce services to reduce care burden. In addition, a thorough explanation of the patient’s symptoms and condition is necessary to reduce distress and anxiety for family caregivers | |||

| Joo EH, Rha SY, Ahn JB, Kang HY. 2011 [58] | South Korea | Quantitative | Therapeutic | Patients | 80 | stage III colorectal cancer |

Discomfort in daily life Burden on family or caregiver Worry about chemotherapy Understanding chemotherapy schedule Explanation for caution and potential side effects Ease of dealing with side effects Ease of managing the injection site Courtesy of medical staff Understanding chemotherapy schedule |

Home-based chemotherapy lessens the discomfort of daily life, worries about chemotherapy, and the burden on caregivers, and it saves costs associated with chemotherapy by avoiding patients’ being hospitalized. However, it is noteworthy that two satisfaction items showed lower satisfaction among patients undergoing home chemotherapy than those undergoing hospital-based chemotherapy: dealing with side effects and managing the injection site | ||

| Kealey P, McIntyre I. 2005 [59] | UK | Mixed methods | Palliative care | Both | 30 | 30 |

Communication Accessibility Be at ease Enough time Co-production Choice Helpfulness Understanding of needs |

This study, although small, does suggest that patients and carers do value and have a high level of satisfaction with the domiciliary occupational therapy service provided. However, gaps have been identified in the service provided to this patient group and their carers | ||

| Klarare A, Rasmussen BH, Fossum B, Hansson J, Fürst CJ, Lundh Hagelin C. 2018 [60] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients; Caregivers | 6 | 7 |

Organising and providing adequate resources Reliability Partnership/co production Disrespect Lack of information Violation of personal space/integrity |

Providing adequate resources, keeping promises and being reliable, and creating partnerships are actions by specialist palliative care teams that patients with advanced cancer and family caregivers experienced as helping in meeting expressed or anticipated needs in patients and families | ||

| Land J, Hackett J, Sidhu G, Heinrich M, McCourt O, Yong KL, Fisher A, Beeken RJ. 2022 [61] | UK | Qualitative | Rehabilitation | Patients | 20 | multiple myeloma |

More complete cancer care Social support Improved physical health Improved self-efficacy Stress Limited engagement Necessity of supervision |

Our interviews of patients completing the MASCOT study highlight that exercise can improve MM patients’ physical function, aid their mental wellbeing, and support them to regain a sense of normality | ||

| Leow MQ, Chan SW. 2017 [62] | Singapore | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 19 |

Helpness Support from professionals |

This study has provided insights into the stress, emotions, and coping of Asian family caregivers caring for family members with advanced cancer in the home. Interventions could also be developed to help caregivers better manage their stress and negative emotions | |||

| Lind L, Karlsson D, Fridlund B. 2008 [63] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 12 |

Ease of use Overcome technical problems Managed to assess the pain Increased and improved contact with the caregivers Increased participation in one’s own care A sense of increased security |

The medical records revealed that there had been a quick medical response to changes in the patients’ health status. The results imply that palliative home care patients’ assessment and self-reporting of pain, with the use of pain diaries together with digital pen and wireless Internet technology, constitute an effortless method and have positive influences on the care given | |||

| Liu X, Liu Z, Zheng R, Li W, Chen Q, Cao W, Li R, Ying W. 2021 [64] | China | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 15 |

Symptom management (need) Prolonging life as long as possible (need) Positive emotion Negative emotion Keeping independence and dignity Concerns about the future Accepting death peacefully Interpersonal communication without discrimination Financial support Government support Information need |

Patients need to manage their symptoms (especially cancer pain), prolong life as long as possible, reconstruct their attitudes to adapt to their roles, be socially supported, be respected, maintain spiritual peace, and obtain more information about illness and home care. To improve the quality of PHC in China, efforts from the government, healthcare providers, and the public are required | |||

| Mack JW, Currie ER, Martello V, Gittzus J, Isack A, Fisher L, Lindley LC, Gilbertson-White S, Roeland E, Bakitas M. 2021 [65] | USA | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 28 |

Suboptimal communication Emotional barriers Limited care options |

Our findings suggest that high rates of intensive EoL care and inpatient deaths among AYAs may not uniformly reflect a desire to pursue all possible options in this young population. Instead, caregivers feel that communication and care delivery may not always meet AYAs’ needs to feel as good as possible and live as long as possible at EoL | |||

| McLaughlin D, Sullivan K, Hasson F. 2007 [66] | UK | Mixed methods | Palliative care | Caregiver | 128 |

Awareness of service Enabling the patient to be cared at home More support (need) Day and night cover Meet the demands Relieving care burden Courtesy of staff |

The carers expressed satisfaction with the quality of the care they had experienced, but did identify areas of improvement in coordination of service delivery and the need for continued support after the death | |||

| Milberg A, Rydstrand K, Helander L, Friedrichsen M. 2005 [67] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 19 |

Coping abilities Meaningful Dialogue Inner strength Relief |

Many family members within palliative home care feel lonely and isolated. They choose not to confide in the persons available. Our results pointed to some important topics that were perceived as taboo in relation to the patient and, therefore, impaired communication, However, this study showed that topics were not taboo in communicating with peers in the support group, and a support group may become an arena for family members to express their needs | |||

| Milberg A, Strang P. 2011 [68] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 233 |

Well coping of patients Trusting Relationship with the Patient Practical and Emotional Support from Family and Friends Talking to someone Doing Good for the Patient Distracting Activities Acceptance, Meaning, and Hope Inner feeling of security Accessibility of Palliative Expertise Staff support Information |

In conclusion, this study has identified several aspects, of clinical relevance, experienced by family members in palliative care as protective against powerlessness and helplessness or as helpful in coping with such experiences. There may actually be several different types of effective coping with loss, and also a need of different types of bereavement support | |||

| Mohammed S, Swami N, Pope A, Rodin G, Hannon B, Nissim R, Hales S, Zimmermann C. 2018 [69] | Canada | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 61 |

Taking charge of the home care Difficulties in access resources and support Engaging with Professional Caregiver Same professional Providers were proactive in providing assistance after death |

Interventions for caregivers should include help with navigating the complexities of the health care system; advocating for their own needs as well as for those of their loved one; understanding what to expect at the end of life; and preparing in advance for tasks after death. In addition, changes are required in the home care system. These include better coordination of care; improved communication of health care professionals with each other and with caregivers; consistency, accessibility and responsiveness among those providing care; and equitable access to adequate and timely support. In conclusion, caregivers contribute importantly to home care, but often receive inadequate formal support |

|||

| Mooney KH, Beck SL, Friedman RH, Farzanfar R. 2002 [70] | USA | Quantitative | Support | Patients | 27 |

Help keep tracking of the symptoms Feeling to participate in own care Human technology |

In its initial test, the TLC chemotherapy monitoring application has been shown to be highly acceptable to patients, able to generate useful symptom data, and able to generate faxed alerts to healthcare providers, thus improving communication about poorly controlled symptoms | |||

| Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Jensen AB, Sondergaard J. 2008 [71] | Denmark | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 14 |

The health professionals' knowledge The health professionals' behaviour and communication skills The professionals' contact with patients and families Professional responsibility Inter-professional culture Inter-professional communication The pressure of being a "semi-professional" |

Our study indicates that relatives experience insufficient palliative care, mainly due to organizational and cultural problems among professionals | |||

| Norinder M, Goliath I, Alvariza A. 2017 [72] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 11 |

Safe at home A Facilitated and More Honest Communication Feeling like a Unit of Care |

Our findings clearly point out the significance of the intervention in supporting family members, as this support was also beneficial for the patients. They felt that their needs were better met and that their family members became more confident about managing the situation at home without putting their own health at risk | |||

| O'Connor M. 2014 [73] | Australia | Qualitative | Palliative care | Patients | 8 |

Loss of social networks Maintaining independence Balancing independence and the need for assistance Remain at home |

Help with using the Internet or giving lifts could make a difference to people living alone with increasing physical difficulties; also helpful is to keep asking about plans for end of life, as these may change | |||

| Oosterveld-Vlug MG, Custers B, Hofstede J, Donker GA, Rijken PM, Korevaar JC, Francke AL. 2019 [74] | The Netherlands | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers; Patients | 13 | 14 |

Medical proficiency Availability A focus on the person Showing personal interest Taking patient and relatives seriously Having a bond of trust Proactivity Making timely arrangements with other care providers Informing patient and relatives in good time Openly discussing end-of-life care Proper collaboration and information transfer between professionals Clear and rapid procedures |

Medical proficiency, availability, a focus on the person, proper information transfer between care professionals, clear and rapid procedures and proactivity on the part of GPs and community nursing staff are considered essential for good palliative primary care at home. Although these essential elements were often fulfilled in the actual experience of patients and relatives, improvements are warranted in particular with regard to collaboration and information transfer between professionals, and current bureaucratic procedures | ||

| Orrevall Y, Tishelman C, Permert J. 2005 [75] | Sweden | Qualitative | Palliative care | Both | 13 | 11 |

Sense of relief and security Restrictions in family life and social contacts Increase in strength and energy Co-decision |

This study indicates that the interviewed cancer patients and their family members experienced physical, social and psychological benefits from HPN treatment. Every patient, with his/her family, is unique and palliative support therefore needs to be flexible, and take a variety of circumstances into consideration | ||

| Jones RV, Hansford J, Fiske J. 1993 [76] | UK | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 207 |

Lack of information about benefits Physical symptoms of caregivers Stable condition Difficulties in getting home visits Lacking of healthcare support |

Although care has improved greatly over the past 10 years, deficit still exist. Many doctors and nurses did not seem to recognise the importance of controlling symptoms other than pain and were unaware of the problems of the carers | |||

| Salifu Y, Almack K, Caswell G. 2021 [77] | UK | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers; Patients | 23 | 23 | 12 | advanced prostate cancer |

Managing sudden change in condition Coordinating care Conflict in care provision Significance of providing food for patients Reciprocity Managing pain at home |

Palliative care services are limited, and in the early stages of development in the study’s context. There is a clear need for person-centred care that is coordinated by both professionals and family caregivers |

| Sowerbutts AM, Lal S, Sremanakova J, Clamp AR, Jayson GC, Teubner A, Hardy L, Todd C, Raftery AM, Sutton E, Morgan RD, Vickers AJ, Burden S. 2019 [78] | UK | Mixed methods | Palliative care | Caregivers; Patients | 20 | 13 | ovarian cancer and inoperable MBO |

Competing priorities Gain survival Gain quality of life Curtailment of activities of daily living Limiting bodily freedom Imposed routine Changes to the meaning of home Changing relationships Stopping HPN Need for a better preparation on dying process |

In conclusion, from patients’ experiences burden of treatment did not mitigate the benefits of HPN. Patients and family caregivers recognise the treatment as a lifeline and are grateful for it | |

| Spelten E, Timmis J, Heald S, Duijts SFA. 2019 [79] | Australia | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregiver | 10 | 4 |

Positive experience Support after death Positive impact on bereavement Efficient and complete Dedication of the nurses |

This study has shown what a positive impact an end-of-life service can have. At the same time, it pointed to concerns of the nursing staff about the sustainability of the model of care and the risk of burnout | ||

| Stern A, Valaitis R, Weir R, Jadad AR. 2012 [80] | Canada | Mixed method | Palliative care | Both | 5 | 12 |

Ease of access to a health care professional Reassurance Enhanced access to pain and symptom management Lack of integration Inappropriate timing of the intervention Lack of portability of the equipment Technical challenges despite ease of use |

The case study confirmed the importance of timely and accessible care for a group of clinically vulnerable, dying cancer patients and their family caregivers | ||

| Strang VR, Koop PM. 2003 [81] | Canada | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 15 |

Formal support Unconditional availability of services Bad scheduling of health services |

Specifically, there needs to be differentiation of formal and informal support, both negative and positive, and how each affects caregiver coping. Finally, exploring the long-term health effects of this home-base caregiving experience on family caregivers should be investigated | |||

| Thomas A, Sowerbutts AM, Burden ST. 2019 [82] | UK | Qualitative | Therapeutic | Patients | 15 | head and neck cancer |

Out of control of own life’s Regaining independence Empowerment Creating a new normality Support from family and friends Coping mechanisms Deviation from normality Knowing what to expect in the future |

HEF was found to influence peoples’ daily lives substantially and required extensive adjustments for individuals to find a new normal | ||

| Totman J, Pistrang N, Smith S, Hennessey S, Martin J. 2015 [83] | UK | Qualitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 15 |

Shared responsibility Sense of security Feel of isolation Explain things Sensitivity shown by professionals |

Feeling unsupported can intensify the burden of responsibility and isolation, whereas attentiveness to relatives’ needs can have powerful effects in assuaging anxiety, reducing isolation and enabling relatives to connect with the positive meaningful aspects of caregiving | |||

| van Harteveld JT, Mistiaen PJ, Dukkers van Emden DM. 1997 [84] | The Netherlands | Quantitative | Support | Patients | 112 |

Possibility to talk and be listened Usefulness of community nurse service Feeling of compassion and zeal |

Those patients who received a visit evaluated this visit mostly as positive | |||

| Wakiuchi J, Marcon SS, Sales CA. 2016 [85] | Brasil | Qualitative | Support | Patients | 10 |

Lack of communication Support and autonomy Lack of empathy |

the understanding of these experiences raises a reflection on the support that is provided in this instance of care and the importance of overcoming impersonal and inauthentic attitudes in order to transcend to a new level of relationship and care |

|||

| Witkowski A, Carlsson ME. 2004 [86] | Sweden | Mixed methods | Palliative care | Relatives; Caregivers | 48 |

Experiences shared among group members Caregivers' involvement Benefit to the patient Health promoting effect |

The subjects emphasised the importance of the opportunity to meet people who are in a similar situation | |||

| Yip F, Zavery B, Poulter-Clark H, Spencer J. 2019 [87] | UK | Quantitative | Therapeutic | Patients | 53 |

Efficiency Safety Reduced travel burden Reduced waiting time Comfort Privacy Continuity of HPs Work life balance |

The ‘Cancer Treatment at Home’ service has improved the patient experience for cancer care and has been recognized nationally for its achievements | |||

| Zavagli V, Raccichini M, Ercolani G, Franchini L, Varani S, Pannuti R. 2019 [88] | Italy | Quantitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 87 |

Caregiving workload Lack of information No interest from healthcare professionals |

The assessment of caregivers’ needs is a critical step for determining appropriate support services, providing high-quality care, achieving caregiver satisfaction, and decreasing caregiver burden | |||

| Zavagli V, Raccichini M, Ostan R, Ercolani G, Franchini L, Varani S, Pannuti R. 2022 [89] | Italy | Quantitative | Palliative care | Caregivers | 251 |

Substantial caregiving workload Negative effects on caregiver own physical health Negative social consequences Need to lead a normal life Awareness of the important things in life |

The analysis demonstrated that cancer caregiving is burdensome. The results can guide the development and implementation of tailored programs or support policies so that FCs can provide appropriate care to patients while preserving their own well-being |

The key elements were extracted and synthesised using the meta-aggregation approach [90] and then systematised using the eight Picker principles of PCC [30]. MFF and FF determined the type of home care in the study. When there were different opinions, GB was involved.

Content analysis was used to identify the expectations and unmet needs of patients and caregivers across quantitative and qualitative studies. Unmet needs were further classified using the categories of the study conducted by Hart and al. [91]. While several reviews have investigated the supportive care needs of cancer patients and their caregivers including those with hematological malignancies, no reviews have investigated the unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer (solid tumors and hematological malignancies) with their informal caregivers [91]. Because this review focuses on patients and caregivers, and because the researchers did not find a specific classification on the needs of oncology patients managed at home and their caregivers, we decided to use the classification proposed by Hart's et al. [91]. MFF and FF have classified the needs of patients and caregivers using the Hart's classification[91].

Results

A total of 847 articles were retrieved from the literature search, with 703 articles remaining after deletion of duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 89 articles remained and were included in the full-text screening. Based upon the established exclusion criteria 32 out of 89 articles were excluded and 57 analysed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the literature screening process

Study design and population

Using the R package Bibliometrix [33], we analysed the countries of affiliation of the corresponding authors. Most of the scientific production on the experience of patient and caregivers for HCC were generated in four countries, two European and two North American, specifically Sweden (n = 15) and the UK (n = 13) are the affiliation countries of half of the corresponding authors (Table 1).

Generally speaking, the number of articles on HCC increased throughout the last three decades, from 2 articles in the period 1990–1992 to 14 articles in the period 2017–2019 (Fig. 2). During the 1990s the number of publications was very low, with 5 articles in 10 years, while since 2000 scientific production has steadily increased.

Fig. 2.

Publication trend (1990–2022)

Most studies had a qualitative design, 43 out of 57 (75%) and used interviews, 40 out of 43 (93%) or surveys with open ended questions, 3 out of 43 (7%), see Table 1. The remaining eight studies, 14%, were quantitative, adopting various questionnaires. Two surveys were conducted using Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs (CaTCoN) [88, 89] while the following questionnaires were used only once: Family Assessment of Treatment at the End of Life (FATE) [54], Family’s Difficulty Scale [57] and Care Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) [35]. Two studies used non-validated questionnaires [70, 87]. Finally, six studies, 10.5%, applied mixed methods, using a combination of surveys and interviews or quantitative and qualitative surveys. One study used the Sympathy Acceptance Understanding Competence questionnaire (SAUC) [18].

The study population consisted mainly of patients and caregivers, but also relatives or health professionals. Surveys were submitted to patients (n = 22), to caregivers (n = 22), both patients and caregivers (n = 9), to patients, caregivers and health professionals (n = 2), to patients, caregivers and other relatives (n = 1) or to other relatives (n = 1), Table 1.

Type of HCC

Patients were at different stages of the oncological illness and therefore received different types of HCC. Most of patients (n = 39) received palliative care, fewer received supportive interventions (n = 8), therapeutic interventions (n = 4) and rehabilitation (n = 3). Finally, three studies examined the recovery phase post hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), Table 1.

Palliative care includes various interventions, like symptom relief, and social and spiritual support. Most studies (n = 26) did not specify the type of HCC interventions for palliative care, while in others they were more clearly specified: end of life care (n = 2), parental nutrition (n = 2), massages (n = 2), support (n = 1) group or remote support of a nurse (n = 1), pain assessment (n = 1), rehabilitation (n = 2) and psychoeducational intervention for a family member (n = 1). One intervention included symptoms management, administration of chemotherapy and telephone support.

Supportive care interventions were nurse home visits (n = 3), pain management (n = 1), support group for family members (n = 1) and enteral feeding (n = 1). The other interventions (n = 2) were not enough described.

Three articles (written by the same authors) described the home care provided after haematopoietic cell transplantation (pancytopenia phase). During this phase experienced nurses from the transplantation centre visited the patients in their homes and patients were contacted by telephone by the doctor.

Therapeutic interventions were related to home chemotherapy. In three studies patients received chemotherapy at home while in one study patients were enterally fed at home.

Articles focused on rehabilitation describe physical rehabilitation interventions, delivered at home after chemotherapy or during the disease.

Experience of patients and caregivers

The findings of the studies (Table 1) reveal many positive experiences related to treatments, services provided, and health professionals. Negative experiences, particularly shortcomings in the services offered, primary concern caregivers. These issues were referred to: support and education [45], preparation for the new role and inclusion as recipients of services [51], services aimed at reducing caregiver burden and stress [71, 77, 89], as well as palliative services and limited caregiver support [71, 77, 89].

Table 2 reports the experience of patients and caregivers according to the Picker Institute classification. For each article included in the review, key elements of the experience were extracted. About one third (26%) of the elements were classified in the category "Emotional support, empathy and respect", and 21% in the category "Clear information, communication, and support for self-care". The category "Emotional support, empathy and respect" includes, for example, the elements “Focus on the person”, “Availability of the staff” and “Support from program staff”, expressing how the patient or caregiver perceives the service provided by healthcare professionals. The category "Clear information, communication, and support for self-care" includes elements like “Information provided and communication” as a positive experience or, on the other side, “Lack of communication”.

Table 2.

Findings from the analysis based on the Picker Principles of Person Centred Care

| Principles | N | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional support, empathy and respect | 55 | [35–38, 40, 41, 44–46, 48, 50, 51, 54–56, 58–62, 65, 66, 70, 74, 75, 79, 80, 83–85, 88, 92–94] |

| Clear information, communication, and support for self-care | 45 | [18, 36, 40, 41, 43–47, 49, 51–55, 58–61, 65, 67, 68, 71, 72, 74, 76, 77, 83–85, 88, 95, 96] |

| Attention to physical and environmental needs | 34 | [17, 36, 38–40, 44, 47, 53–55, 57, 58, 60, 64, 66, 70, 72, 73, 75, 78, 83, 87, 97] |

| Involvement in decisions and respect for preferences | 20 | [35, 44, 49, 52, 54, 56, 59, 60, 63, 70, 72, 74, 77, 83, 86] |

| Continuity of care and smooth transitions | 18 | [40, 44, 69, 71, 74, 77, 80, 87, 98] |

| Involvement and support for family and carers | 14 | [12, 35, 39, 45, 53, 55, 56, 61, 63, 66, 75, 81, 82, 87, 88, 99, 100] |

| Fast access to reliable healthcare advice | 12 | [43, 47, 54, 59, 69, 74, 76, 80, 81, 87, 99] |

| Effective treatment delivered by trusted professionals | 11 | [18, 36, 60, 65, 71, 74, 79, 87] |

| Total | 209 |

N: Number of key elements extracted from the articles

“Attention to physical and environmental needs “accounts for 16% of the total, while none of the other categories reach 10%. This last category includes various elements, e.g. “Reduced travel burden”, “Privacy”, “Sense of security” and “Safety”.

The analysis also shows that five articles [44, 54, 60, 74, 87] relate to five or more items of the framework, but no article has all categories. These articles share common characteristics: the interventions are palliative or for patients at the end of life, and they were published after 2018.

Throughout the years, the frequency with which the principles are considered has changed. The following results are shown in detail in an additional file [see Additional file 2]. In the articles published in the 1990s, “Communication and emotional support” emerged above all, while "Involvement in decisions and respect for preferences" and "Involvement and support for family and carers “ were poorly represented. In the following 20 years, “Communication and emotional support” continued to be very present, and more attention was paid to “Environmental and physical needs”. The principles referring to organisational aspects, rapid access, and smooth transition are underrepresented in all articles.

The various components of the experience could be positive or negative. The table in the additional file [see Additional file 2] also summarises the assessment of the experience expressed by patients and/or caregivers: in green is the positive experience and in orange the negative experience. If the experience was both positive and negative, the colour is golden yellow. The rating of the dimensions has changed over the years. "Attention to physical and environmental needs", "Clear information, communication and support for self-care" and "Emotional support, empathy and respect" seem to have worsened in recent years. “Continuity of care and smooth transitions” and “Fast access to reliable healthcare advice” show, however, an improving trend. "Involvement in decisions and respect for preferences" and "Involvement and support for family and carers " seem to worsen in the years 2019–2021. “Effective treatment delivered by trusted professionals” appears to have been consistently positive.

Table 3 describes caregivers’ and patients’ reported needs and their classification according to Hart N. H. et al., 2022 [91]. This literature review describes the unmet needs for supportive care of people with advanced cancer within the following domains: Financial, Health System and Information Needs, Psychological Physical and Daily Living, Patient Care and Support, Relationships and Social [91]. Caregivers' needs can be classified in most (29%) of the cases as relational and social needs, followed by “Physical and Daily Living Needs” (23,5%) and “Psychological Needs” (17,6%). Only about 12% report unmet needs regarding “Health System and Information”. From the patient’s perspective, the most common needs fall into the categories “Health System and Information” 43,8%, “Physical And Daily Living”, 31,3% and “Relationship And Social Needs” 18,8%. “Psychological needs” account for 6,3%.

Table 3.

Caregivers’ and patients’ needs

| Caregivers’ needs (citation) | Classification |

|---|---|

| Balance of work and care [101] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Doing Good for the Patient [99] | Patient care and Support |

| Feeling Connected with the Patient [41] | Psychological |

| Having time for yourself during the day [35] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Managed to assess the pain despite one’s health condition [63] | Patient Care and Support |

| Managing sudden changes in condition [77] | Patient Care and Support |

| Need for better preparation for the dying process [78] | Health System And Information |

| Need to lead a normal life [89] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Negative effects on caregiver's physical health [89] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Patient’s pain and condition [50] | Patient Care and Support |

| Realignment of resources with values and effects on caregivers [17] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Reciprocity [77] | Psychological And Patient Care Needs |

| Set limits on caregiving roles [56] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Substantial caregiving workload [89] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Support after death [79] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Talking to someone [102] | Psychological |

| Trusting Relationship with the Patient [68] | Psychological |

| Understanding your relative’s illness [35] | Health System And Information |

| Patients’ needs | |

| Balancing independence and the need for assistance [73] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Being able to work [39] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Easiness in using the equipment despite severe illness and difficulties in comprehending the technology and system intervention [63] | Health System And Information |

| Good to track progress [52] | Health System And Information |

| Imposed routine [78] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Maintaining independence [73] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| More complete cancer care [61] | Health System And Information |

| More information [35] | Health System And Information |

| My way of taking control [38] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Prolonging life as long as possible [64] | Health System And Information |

| Realignment of resources with values [17] | Psychological |

| Regaining independence [82] | Relationship And Social Needs |

| Remain at home [73] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Satisfaction to be home [36] | Physical And Daily Living Needs |

| Symptom management [64] | Health System And Information |

| Understanding chemotherapy schedule [58] | Health System And Information |

Discussion

The review indicates that the first articles on the evaluation of HCC date back to the early 1990s, confirming that home care for cancer patients is not a new concept (Fig. 2). The publication of research about home care interventions for cancer patients has steadily increased over the past three decades [12]. This increase can be attributed to both the introduction of new opportunities for home oncology interventions, their wider use, and the improved attention to patients' and caregivers’ experiences within the healthcare domain, in line with the value-based paradigm [103]. However, HCC has not received equal attention around the world. By far, most publications have come from Sweden, with notable contributions from other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, as well as North American countries. This distribution can be partly explained by the different health policies adopted by countries regarding home care. For example, Sweden has supported its elderly population in preferring ordinary housing over nursing homes, and national policies promote home care over institutionalised care [104]. In general, these findings are consistent with the prevalence of home care provision or practices in developed countries [12]. Regarding temporal evolution, the eight principles on which the Picker framework is based, have remained present over the years, though with differences in frequency. No dimension shows a clear temporal trend. Three principles are the least represented in the time series, “Fast access to reliable healthcare advice”, “Continuity of care and smooth transitions” and “Effective treatment delivered by trusted professionals”. Continuity of care and fast access pertain to the organisation of healthcare services and continuity of care, areas where many healthcare organisations focus their efforts. In contrast to a recent systematic review, which reported care coordination as suboptimal, these principles received an overall positive rating in our study [105].

Among the methods employed to investigate the patient’s and carer’s experience, qualitative methods, especially interviews, prevailed. Indeed, measures like patient interviews help to obtain an in-depth description, which enables a richer understanding of the patient experience [106]. On the other hand, quantitative approaches were mostly based on survey administration. The most commonly validated questionnaires used to understand the experience of caregivers or relatives of the patients are Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs (CaTCoN), Family Assessment of Treatment at the End of Life (FATE), Family’s Difficulty Scale, Care Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT). Patients' experience was investigated through the Sympathy Acceptance Understanding Competence questionnaire (SAUC).

Table 1 reports the analysis of the literature identified different types of home cancer assistance, which were grouped into four main categories: palliative care, support care, therapeutic care, and rehabilitation care. Palliative care has been the focus of research about home-based intervention; often the term home cancer care is used in association with palliative and end-of-life care for advanced cancer patients [12, 107]. Therefore, home-based palliative care concerns pain and symptom management, and psychological, social and spiritual support to improve the quality of life of patients and their family caregivers [108]. However, most of the articles did not describe in detail the home interventions included in the palliative care intervention.

Supportive care was highly varied and poorly defined in the reviewed publications. As defined by Marthick M et al., supportive care focuses on “assisting people with cancer and their families to cope with the disease and its treatment” [109] thus providing support during cancer treatment. However, supportive care and palliative care are often used interchangeably [110]. We placed these two interventions in separate categories because of the different nature of the interventions: supportive care is highly correlated and focus on reducing toxicity of cancer treatments, while palliative care concerns symptom control in advanced disease [107]. Administration of home-based chemotherapy and enteral feeding were included in the category “therapeutic interventions”. Home based chemotherapy has gained attention in the last years, given evidence of the viable alternative to outpatient chemotherapy.

We found two articles that described the use of technology for remote monitoring, one placed in the category under supportive interventions [38] and one in the therapeutic category [40].

The multidisciplinary field of oncology rehabilitation seeks to reduce disability and improve survivors' functioning [111]. Three articles describe rehabilitation interventions, a very small number out of the total number of home-based interventions reviewed. This finding is in line with the literature [112] and can be explained by two factors: an insufficient number of rehabilitation specialists with expertise in oncology and patients' difficulties in accessing rehabilitation services, especially if they must travel long distances to do so [113, 114]. The latter factor could be overcome through the implementation of home-based services.

In our review, two articles, [63, 80] focused on the use of telemedicine in palliative care. In the second article [80], patients and families received nursing support via telehealth (telephone or telemonitoring). The evaluations of the experience included ease of use of the technology, lack of portability of the equipment, and integration with on-site visits. The other study [63] reports the usefulness of a follow-up system, a pain diary and a digital pen, to monitor pain. Despite severe illness and some difficulties in comprehending the technology and system intervention, patients found the pain diary and digital pen easy to use for pain assessment.

In the support setting, one article [47] described a mobile telephone-based remote symptom monitoring system which was used to log and manage the side effects of chemotherapy in the home care setting. From the analysis of findings, patients receiving cancer care at home reported positive perspectives on the use of healthcare technology, while there were implications for how nurses view the relationship of technology with patients and for power dynamics in healthcare relationships [47]. The second article describes a telephone-based computerised system to monitor post-chemotherapy symptoms [70]. Patient satisfaction with the system was high, therefore the chemotherapy monitoring application showed promise for improving supportive-care service delivery for cancer patients [70].

Despite the variety of HCC interventions and individual conditions, we found consistent results about patients’ and caregivers’ experiences, as well as needs and concerns. The most recurrent aspects of the patients' experience concerned “Emotional support, empathy and respect”, “Information, clear communication and support” and “Attention to physical and environmental needs”. Research speaks out about the relevance that patients and carers place on emotional support and communication with the staff or institution providing the service. For many cancer patients and their families, the experience of cancer is an intensely stressful one, and emotional support is the most valued aspect of coping with it. Emotional care should be considered a responsibility of all healthcare providers [115]. The fact that a person's concerns or needs are respected or acknowledged, even if a clinician cannot address them directly, is recognised as important for supporting emotional well-being [116]. Moreover, the review suggests that both patients and carers value receiving continuous, simple, and effective information, as well as direct communication with professionals about the cancer trajectory and opportunities for better coping with the disease. Patients and caregivers expect improvements in their relationship with healthcare professionals or services, respectively, in order to feel more empowered, ease their burden, and foster better collaboration. Emotional support and clear communication must be allocated dedicated time and space within the healthcare service organizations.

Considering the needs analysis, the needs of patients and caregivers are different. The needs of caregivers concern both individual needs (Relationship and Social Needs) and the needs of the assisted person (Patient Care and Support). These findings agree with those presented by Wang T. et al. 2018 [117] but differ concerning psychological ones. In our study, a strong need for psychological support does not emerge either for patients or caregivers, unlike previous studies in which psychological needs were among the most cited [91, 117].

Health technologies may play a crucial role in facilitating PCC; however, researchers argue that there are several challenges in implementing technology within actual practices [118]. These findings are further supported by a recent systematic review of the use of telemedicine in home-based palliative care programs. According to the results of this study, telemedicine meets the principles of Picker’s framework and addresses the needs of many patients: it enables patients to remain in their homes, reduces travel burdens and expenses, and enhances communication and support, benefiting both patients and healthcare providers [116]. However, our review highlights the need for patients to have access to technological tools that are reliable and easy to use independently. From the point of view of healthcare providers, technology-supported person-centred care is already an integral part of the future of healthcare services. Frameworks for the implementation of technology-supported PCC have already been theorised, e.g. the NASS framework (non-adoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability) [119]. Moreover, after the Covid-19 pandemic, governments moved quickly to promote the use of telemedicine [120]. In our opinion, technology can support PCC if developed and implemented according to the principles already present in the Picker framework. In addition, a technology-specific dimension should be included within the framework. If we want to encourage patients to play an active role in their care, the technology must be easy to use, reliable and integrated with other healthcare services.

This study has limitations. The methods, scope and quality of the included studies differed widely. In many studies, the type of intervention to which the patient was subjected was not specified. This happened especially in palliative care, whereby the interventions were identified under the broad definition of palliative care as well as in the case of supportive interventions. Another limitation is the choice to search for articles in English only which prevents from analysing broader literature.

In a recent published article [121], cancer type was associated with varying frequency of need type and the percentage of patients whose needs were not met. Analysis by cancer type was not conducted, and this is a limitation in generalizing the results regarding needs. Further studies are needed to understand whether sociodemographic factors and tumor type are significantly associated with the home care setting.

Conclusion

This scoping review considered the experience of cancer patients treated at home and of their caregivers. The frame of reference is centred on the person, viewing the patient not merely as a sick individual but as a person embedded in a network of relationships that also encompasses those close to them. From the analysis of retrieved literature, communication and emotional support emerge as the main elements characterizing the experience with healthcare services, while continuity of care and transition does not seem to influence the experience of care. This description is consistent with previous studies but additionally provides an accurate picture of the experience of HCC. The experience of cancer patients and especially caregivers with home services appears to be only partially investigated. Substantial heterogeneity in study populations and cancers has been observed. The uniqueness of the setting and the relationship between cancer patient and caregiver represent a context of care that requires further study to deliver high-quality health care.

Furthermore, as telemedicine is increasingly used in the home, a dimension related to technology and telemedicine could be added to Picker's framework. The findings of this study will help policymakers support informed decision-making about new HCC programs.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Research query. The file collects the search queries used in the three databases.

Supplementary Material 2. Experience evaluation according to the Picker framework, temporal analysis. The table shows articles selected for the review in chronological order. The dimensions of the Picker framework extracted from each item are highlighted and the colour indicates whether the experience was positive, negative or both.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PCC

Person Centred Care

- HCC

Home cancer care

- PMS

Performance Measurement Systems

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and development of the search algorithms. M.F.F. carried out the database search, data extraction, and wrote the original draft. M.F.F. and F.F. analysed the articles . F.F. and G.B. reviewed and edited the manuscript. F.F. provided supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All articles analyzed in this literature review are listed in the Reference section, and can be accessed coherently with the access policy of the publisher.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Main causes of mortality | Health at a Glance: Europe 2022 : State of Health in the EU Cycle | OECD iLibrary. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/a72a34af-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/a72a34af-en. Cited 2023 Feb 19.

- 2.Dalmartello M, La Vecchia C, Bertuccio P, Boffetta P, Levi F, Negri E, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2022 with focus on ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(3):330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Data explorer | ECIS. Available from: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/explorer.php?$0-4$1-AE27$4-1,2$3-0$6-0,85$5-All$7-7$21-0$CLongtermChart3_1$X0_14-$CLongtermChart3_2$X1_14. Cited 2023 Feb 8.

- 4.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Devasia T, Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Jemal A, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(5):409–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt H. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2016. p. 137–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips JL, Currow DC. Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian. 2010;17(2):47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, Sullivan R. Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: a population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(12):1165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert SD, Levesque JV, Girgis A. The impact of cancer and chronic conditions on caregivers and family members. In: Cancer and chronic conditions. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. p. 159–202.

- 9.Accelerating the Delivery of Cancer Care at Home During the Covid-19 Pandemic | Catalyst non-issue content. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0258. Cited 2023 Feb 8.

- 10.Laughlin AI, Begley MG, Delaney T, Zinck L, Schuchter LM, Doyle J, et al. Accelerating the delivery of cancer care at home during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nejm Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery [Internet]. 2020 Jul 7 [cited 2024 Dec 16]; Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=981f5bc6-48d2-4e2a-a9cc-740c1d072557.

- 11.Pennucci F, De Rosis S, Murante AM, Nuti S. Behavioural and social sciences to enhance the efficacy of health promotion interventions: redesigning the role of professionals and people. Behav Public Policy. 2022;6(1):13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fhoula B, Hadid M, Elomri A, Kerbache L, Hamad A, Al Thani MHJ, et al. Home cancer care research: a bibliometric and visualization analysis (1990–2021). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorochan M, Health BBW, 1994 undefined. Does home care save money? apps.who.intM Sorochan, BL BeattieWorld Health, 1994•apps.who.int [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 16]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328389/WH-1994-Jul-Aug-p18-19-eng.pdf.

- 14.Home care in Europe: the solid facts. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328766. Cited 2023 Mar 27.

- 15.Geiger AM, O’Mara AM, McCaskill-Stevens WJ, Adjei B, Tuovenin P, Castro KM. Evolution of cancer care delivery research in the NCI community oncology research program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(6):557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reid RJ, Johnson EA, Hsu C, Ehrlich K, Coleman K, Trescott C, et al. Spreading a medical home redesign: effects on emergency department use and hospital admissions. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crisp N, Koop PM, King K, Duggleby W, Hunter KF. Chemotherapy at home: keeping patients in their “natural habitat.” Can Oncol Nurs J. 2014;24(2):89–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergkvist K, Larsen J, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Svahn BM. Hospital care or home care after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation - Patients’ experiences of care and support. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(4):389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins Susannah, MCMCMSMNP. Medical homes and cost and utilization among high-risk patients. Am J Managed Care. 2014;20(3):e61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.David G, Gunnarsson C, Saynisch PA, Chawla R, Nigam S. Do patient-centered medical homes reduce emergency department visits? Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):418–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepperd S, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Straus SE, Wee B. Hospital at home: home-based end-of-life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021(3):CD009231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness – A systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, Zelinsky S, Quan H, Lu M. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):429–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.People-Centred Health Care. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. Cancer caregiving tasks and consequences and their associations with caregiver status and the caregiver’s relationship to the patient: a survey. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller E. How is person-centred care understood and implemented in practice? 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. 2015. p. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paparella G. Person-centred care in Europe: a cross-country comparison of health system performance, strategies and structures. 2016 [cited 2024 Dec 16]; Available from: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c63361de-f65d-4d71-beef-3d63b0c70615/files/sj9602143b.

- 30.The Picker Principles of Person Centred care - Picker. Available from: https://picker.org/who-we-are/the-picker-principles-of-person-centred-care/. Cited 2023 Jul 20.

- 31.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on quality of health care in America. Book: crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. BMJ. 2001;323(7322):1192. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Handley SC, Bell S, Nembhard IM. A systematic review of surveys for measuring patient-centered care in the hospital setting. Med Care. 2021;59(3):228–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aria M, Cuccurullo C. bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informet. 2017;11(4):959–75. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tufanaru C. Theoretical foundations of meta-aggregation: insights from Husserlian phenomenology and American pragmatism. 2016 [cited 2024 Dec 16]; Available from: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/98255.

- 35.Aoun SM, Deas K, Howting D, Lee G. Exploring the support needs of family caregivers of patients with brain cancer using the CSNAT: a comparative study with other cancer groups. PloS One. 2015;10(12):e0145106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appelin G, Berterö C. Patients’ experiences of palliative care in the home: a phenomenological study of a Swedish sample. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(1):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15(11):541–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergkvist K, Fossum B, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Larsen J. Patients’ experiences of different care settings and a new life situation after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Cancer Care [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Dec 16];27(1):e12672. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ecc.12672. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Bergkvist K, Larsen J, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Fossum B. Family members’ life situation and experiences of different caring organisations during allogeneic haematopoietic stem cells transplantation-A qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Dec 16];27(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27859940/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Rodriguez C. The stress process in palliative cancer care: a qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(2):111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capodanno I, Rocchi M, Prandi R, Pedroni C, Tamagnini E, Alfieri P, et al. Caregivers of patients with hematological malignancies within home care: a phenomenological study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cronfalk BS, Strang P, Ternestedt BM, Friedrichsen M. The existential experiences of receiving soft tissue massage in palliative home care–an intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(9):1203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duggleby WD, Penz KL, Goodridge DM, Wilson DM, Leipert BD, Berry PH, et al. The transition experience of rural older persons with advanced cancer and their families: a grounded theory study. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edbrooke L, Denehy L, Granger CL, Kapp S, Aranda S. Home-based rehabilitation in inoperable non-small cell lung cancer-the patient experience. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(1):99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrell BR, Cohen MZ, Rhiner M, Rozek A. Pain as a metaphor for illness. Part II: Family caregivers’ management of pain. Oncol Nurs Forum [Internet]. 1991 [cited 2024 Dec 16];18(8):1315–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1762972/. [PubMed]

- 46.Ferrell BR, Taylor EJ, Grant M, Fowler M, Corbisiero RM. Pain management at home. Struggle, comfort, and mission. Cancer nursing. 1993;16(3):169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forbat L, Maguire R, McCann L, Illingworth N, Kearney N. The use of technology in cancer care: applying Foucault’s ideas to explore the changing dynamics of power in health care. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]