Abstract

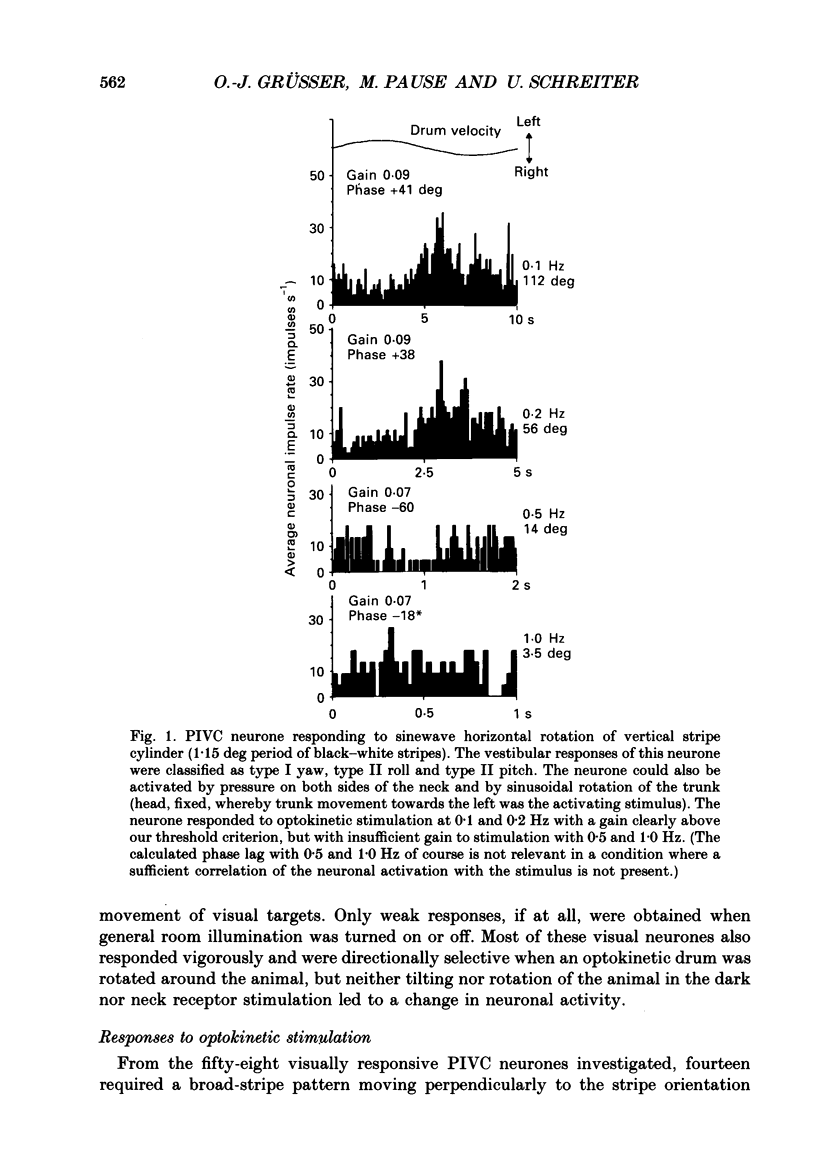

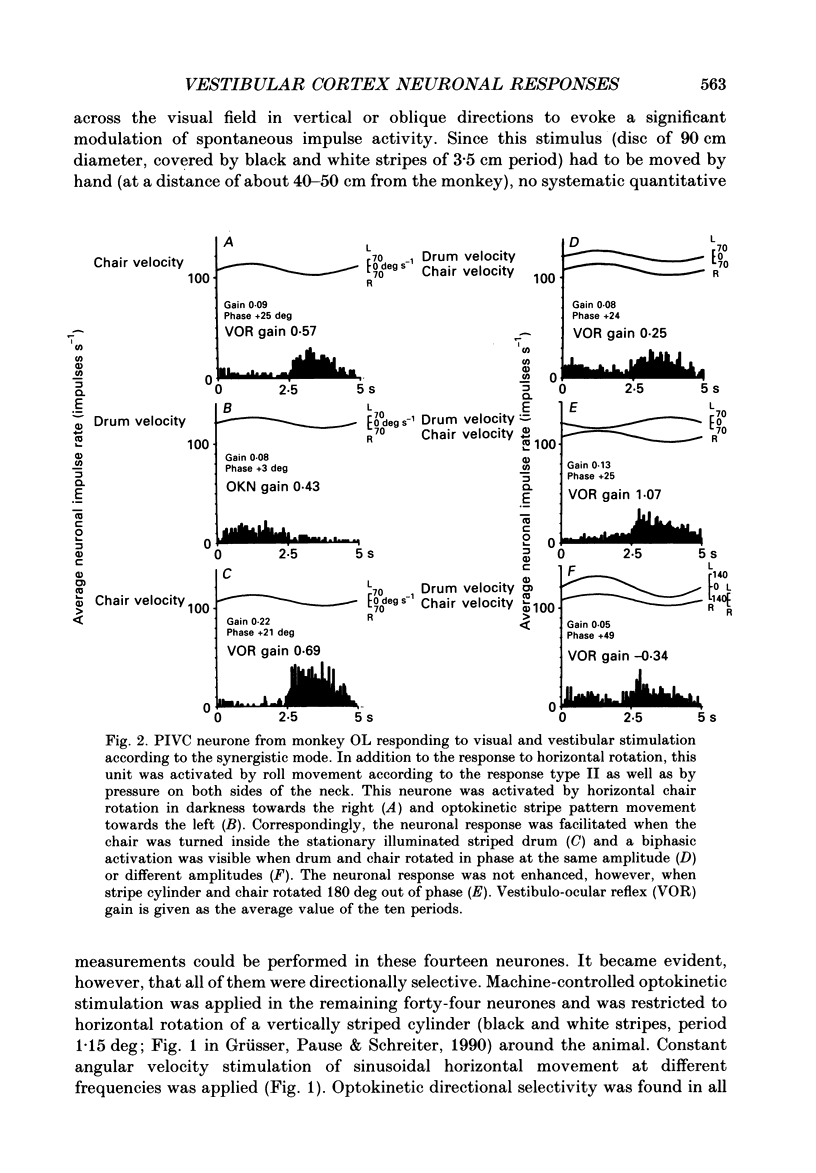

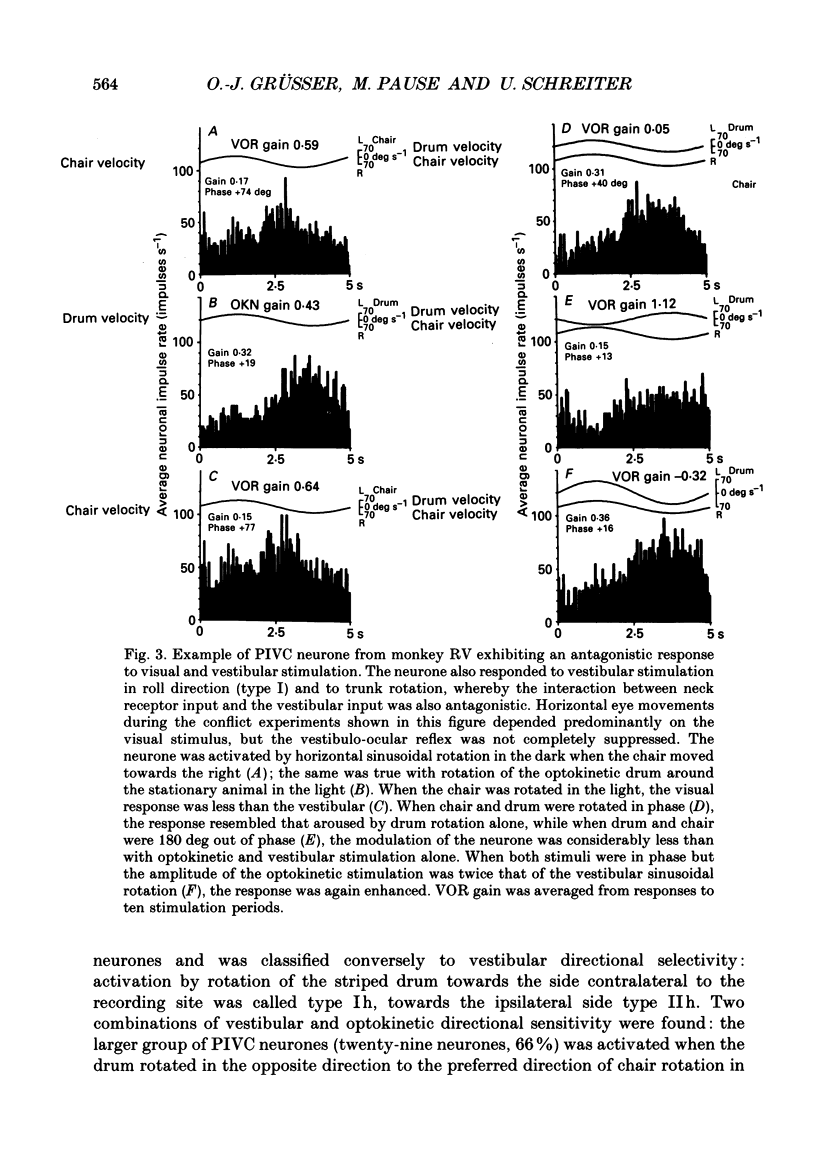

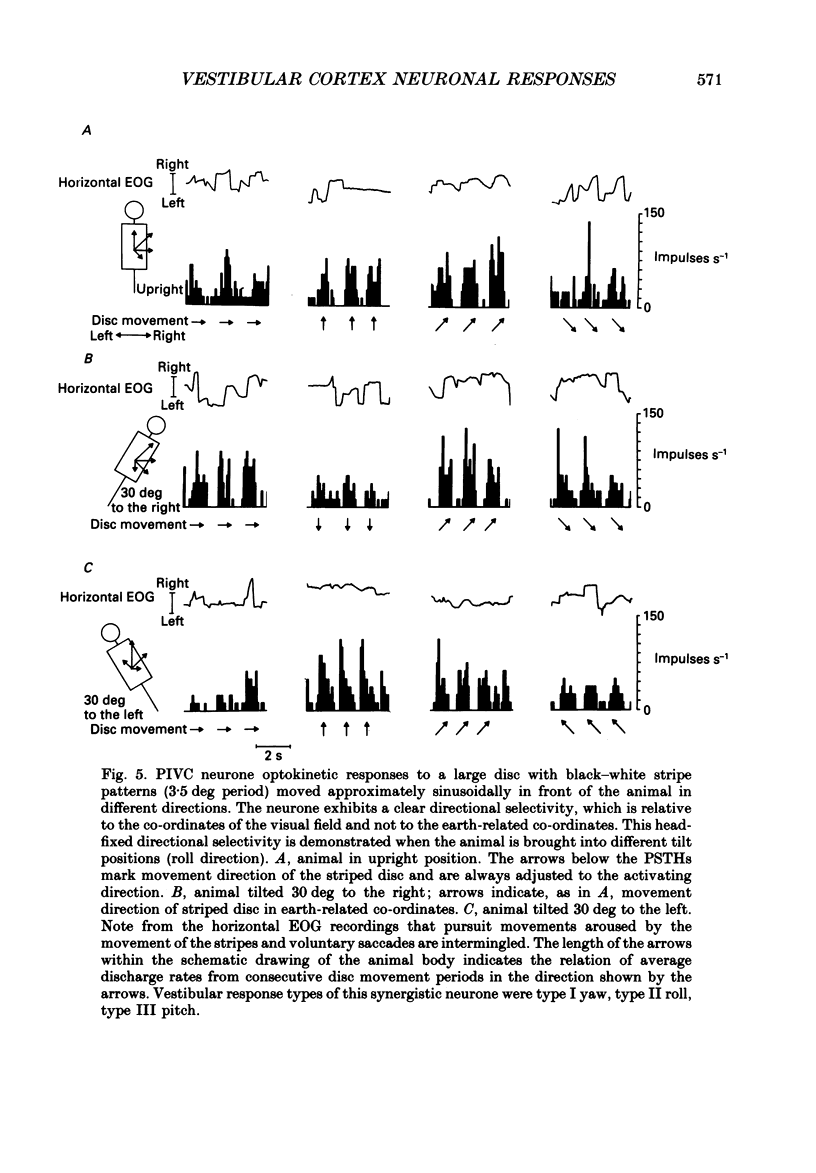

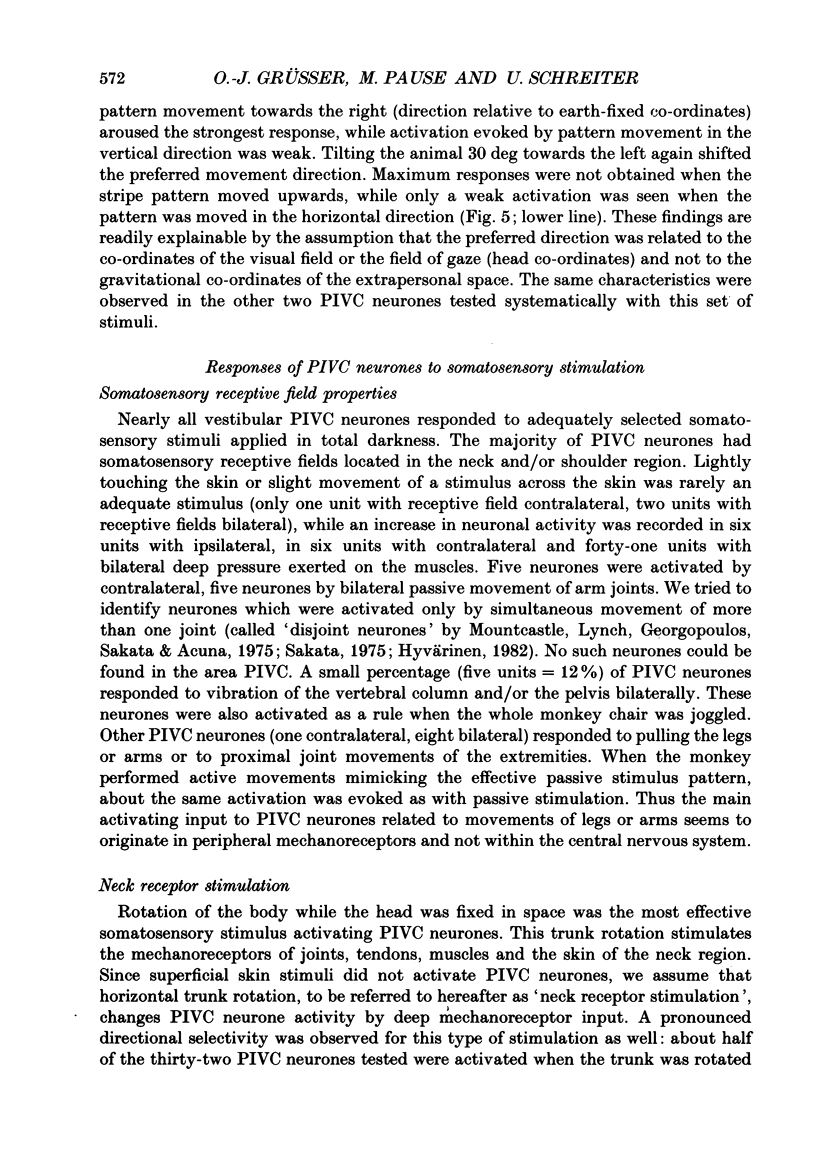

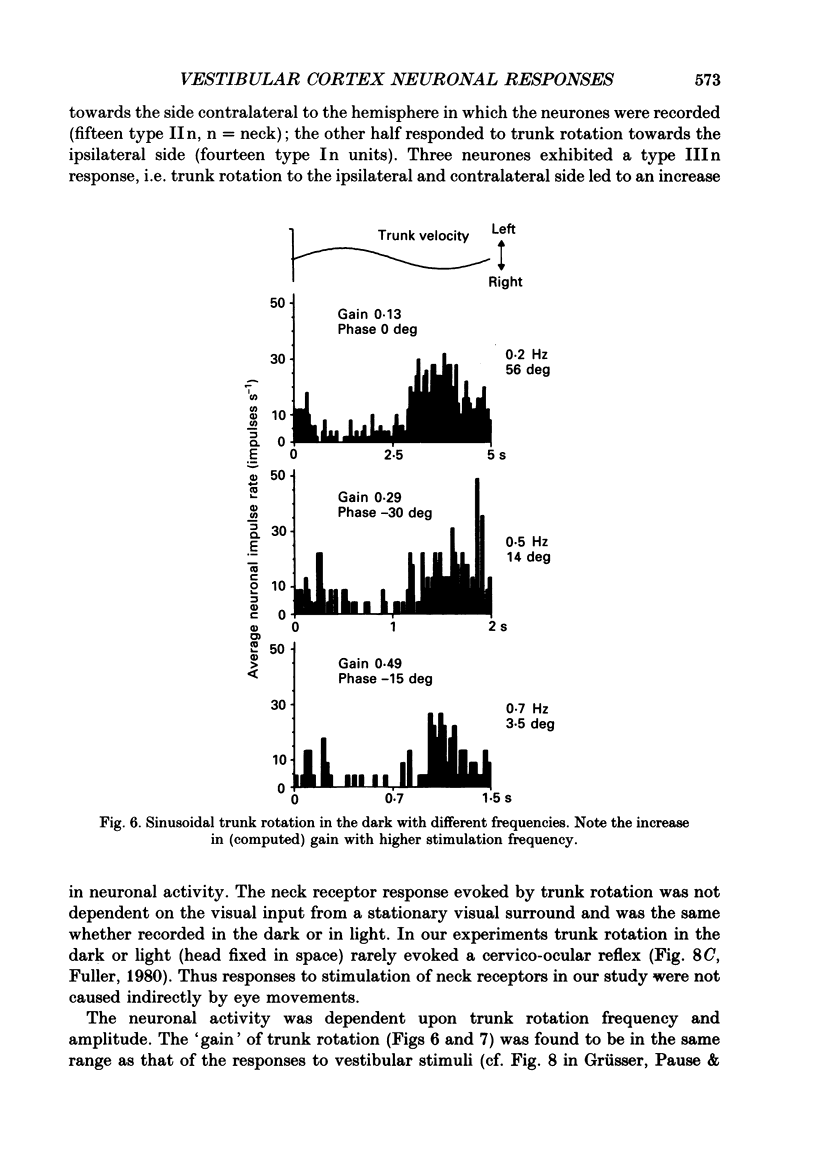

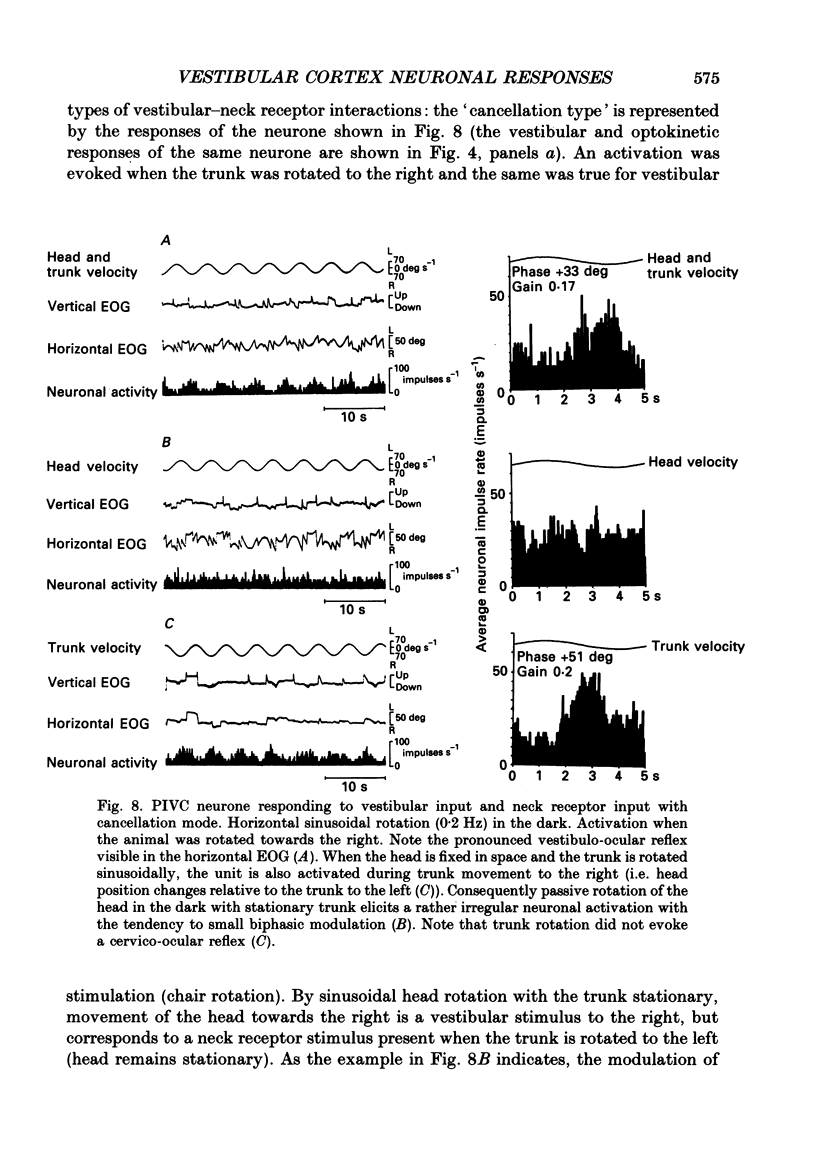

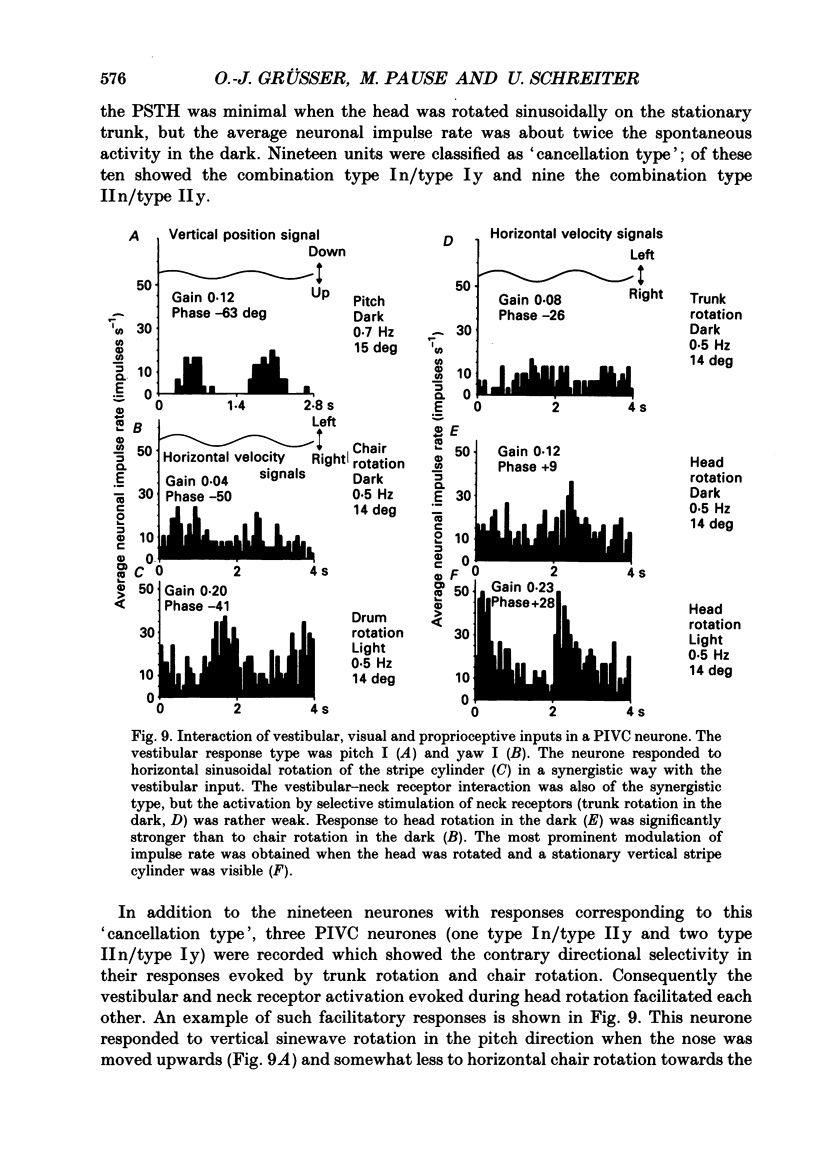

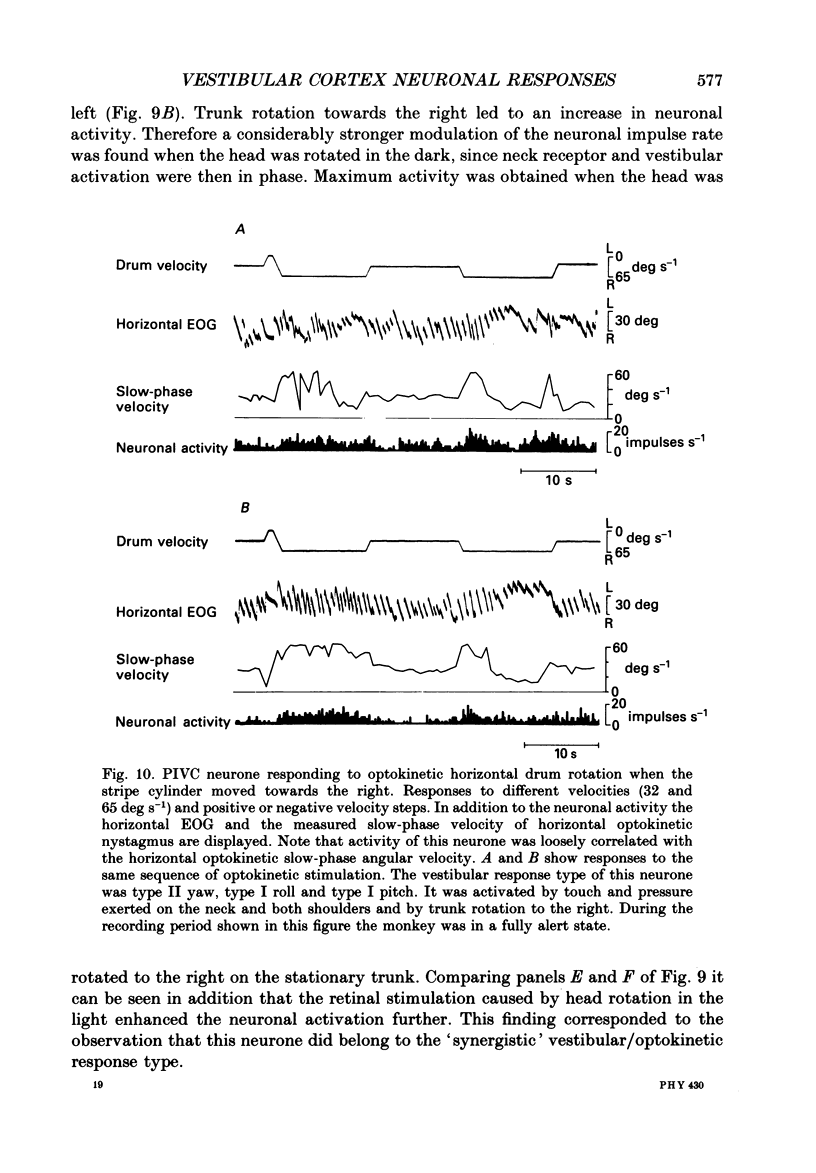

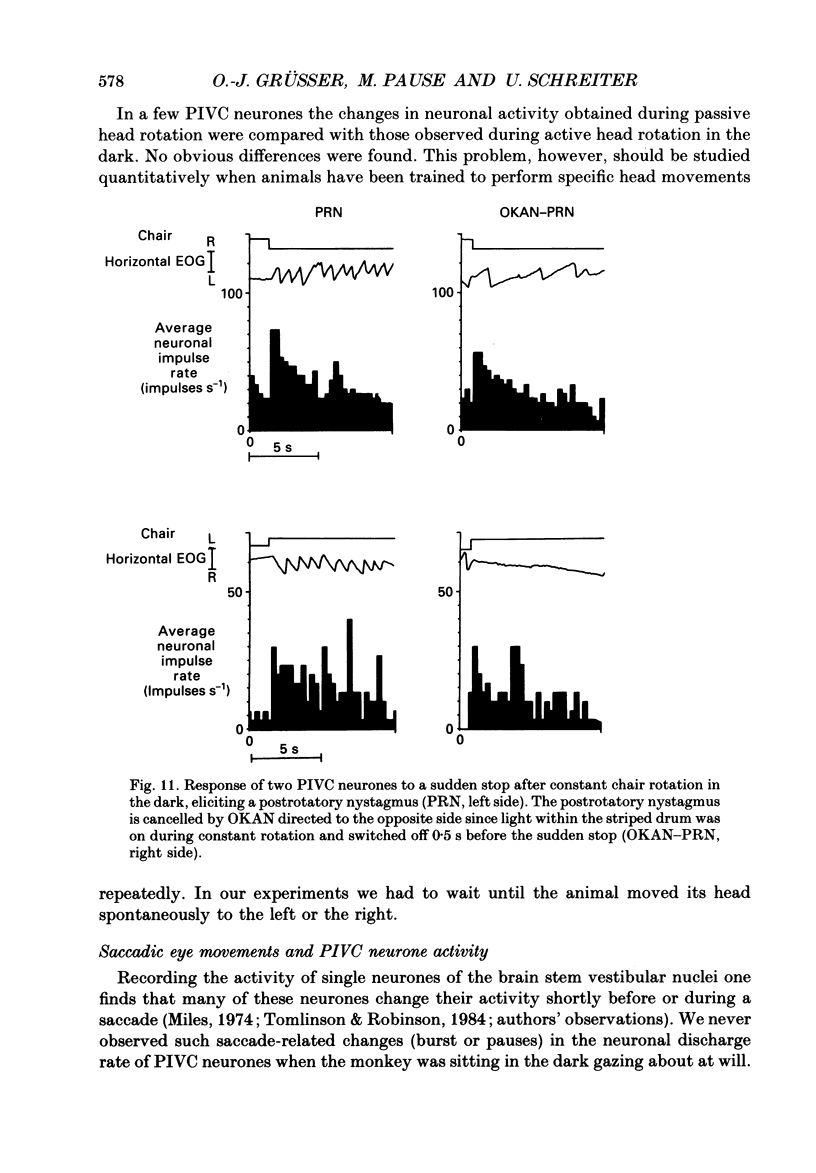

1. One hundred and fifty-two vestibularly activated neurones were recorded in the parieto-insular vestibular cortex (PIVC) of four awake Java monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): sixty-two were tested systematically with visual stimulation and seventy-nine were tested with various somatosensory stimuli. With very few exceptions all vestibular neurones tested responded to visual and somatosensory stimulation, therefore being classified as polymodal vestibular units. 2. A most effective stimulus for all fifty-eight visually activated PIVC units was movement of a large structured visual pattern in an optimal direction. From forty-four units responsive to a horizontally moving optokinetic striped drum, twenty-nine were activated with optokinetic movement in the opposite direction to the activating vestibular stimulus ('synergistic' response), thirteen were activated optokinetically and vestibularly in the same direction ('antagonistic' responses) and two were biphasic. The gain of the optokinetic response to sinusoidal stimulation (average 0.28 (impulses s-1) (deg s-1)-1 at 0.2 Hz, 56 deg amplitude) was in a range similar to that of the vestibular gain at low frequencies. At 1 Hz some units only showed weak optokinetic responses or none at all, but the vestibular response was still strong. 3. With different 'conflicting' or 'enhancing' combinations of optokinetic and vestibular stimulation no generalized type of interaction was observed, but the responses varied from nearly 'algebraic' summation to no discernible changes in the vestibular responses by additional optokinetic stimuli. With all visual-vestibular stimulus combinations the responses to the vestibular stimulus remained dominant. 4. The optokinetic preferred direction was not related to gravitational coordinates since the optokinetic responses were related to the head co-ordinates and remained constant with respect to the head co-ordinates at different angles of steady tilt. 5. Almost all PIVC units were activated by somatosensory stimulation, whereby mainly pressure and/or movement of neck and shoulders (bilateral) and movement of the arm joints elicited vigorous responses. Fewer neurones were activated by lightly touching shoulders/arms or neck, by vibration and/or pressure to the vertebrae, pelvis and legs. 6. A most effective somatosensory stimulus was sinewave rotation of the body with head stationary. The gain of this directionally selective neck receptor response was in the range of vestibular stimulation. Interaction of vestibular and neck receptor stimulation was either of a cancellation or facilitation type.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akbarian S., Berndl K., Grüsser O. J., Guldin W., Pause M., Schreiter U. Responses of single neurons in the parietoinsular vestibular cortex of primates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;545:187–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb19564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasopoulos D., Mergner T. Canal-neck interaction in vestibular nuclear neurons of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1982;46(2):269–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00237185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker D. A., Richmond F. J. Muscle spindle complexes in muscles around upper cervical vertebrae in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1982 Jul;48(1):62–74. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W., Deecke L., Mergner T. Neuronal responses to natural vestibular and neck stimulation in the anterior suprasylvian gyrus of the cat. Brain Res. 1979 Apr 6;165(1):139–143. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bles W., de Jong J. M. Cervico-vestibular and visuo-vestibular interaction. Self-motion perception, nystagmus, and gaze shift. Acta Otolaryngol. 1982 Jul-Aug;94(1-2):61–72. doi: 10.3109/00016488209128890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle R., Pompeiano O. Frequency response characteristics of vestibulospinal neurons during sinusoidal neck rotation. Brain Res. 1979 Sep 14;173(2):344–349. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner U. W., Büttner U. Vestibular nuclei activity in the alert monkey during suppression of vestibular and optokinetic nystagmus. Exp Brain Res. 1979;37(3):581–593. doi: 10.1007/BF00236825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner U., Buettner U. W. Parietal cortex (2v) neuronal activity in the alert monkey during natural vestibular and optokinetic stimulation. Brain Res. 1978 Sep 22;153(2):392–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner U., Henn V. Circularvection: psychophysics and single-unit recordings in the monkey. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1981;374:274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb30876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner U., Henn V. Thalamic unit activity in the alert monkey during natural vestibular stimulation. Brain Res. 1976 Feb 13;103(1):127–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deecke L., Schwarz D. W., Fredrickson J. M. Vestibular responses in the rhesus monkey ventroposterior thalamus. II. Vestibulo-proprioceptive convergence at thalamic neurons. Exp Brain Res. 1977 Nov 24;30(2-3):219–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00237252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J. M., Schwarz D., Kornhuber H. H. Convergence and interaction of vestibular and deep somatic afferents upon neurons in the vestibular nuclei of the cat. Acta Otolaryngol. 1966 Jan-Feb;61(1):168–188. doi: 10.3109/00016486609127054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller J. H. The dynamic neck-eye reflex in mammals. Exp Brain Res. 1980;41(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00236676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRUESSER O. J., GRUESSER-CORNEHLS U., SAUR G. [Reactions of various neurons in the optic cortex of the cat after electrical polarization of the labyrinth]. Pflugers Arch Gesamte Physiol Menschen Tiere. 1959;269:593–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüsser O. J., Pause M., Schreiter U. Localization and responses of neurones in the parieto-insular vestibular cortex of awake monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). J Physiol. 1990 Nov;430:537–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henn V., Young L. R., Finley C. Vestibular nucleus units in alert monkeys are also influenced by moving visual fields. Brain Res. 1974 May 10;71(1):144–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper J., Thoden U. Effects of natural neck afferent stimulation on vestibulo-spinal neurons in the decerebrate cat. Exp Brain Res. 1981;44(4):401–408. doi: 10.1007/BF00238832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano K., Sasaki M., Yamashita M. Response properties of neurons in posterior parietal cortex of monkey during visual-vestibular stimulation. I. Visual tracking neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1984 Feb;51(2):340–351. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano K., Sasaki M., Yamashita M. Vestibular input to visual tracking neurons in the posterior parietal association cortex of the monkey. Neurosci Lett. 1980 Apr;17(1-2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinke R., Galley N. Efferent innervation of vestibular and auditory receptors. Physiol Rev. 1974 Apr;54(2):316–357. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1974.54.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin M., Fuchs A. F. Discharge properties of neurons in the monkey thalamus tested with angular acceleration, eye movement and visual stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 1977 Jun 27;28(3-4):293–299. doi: 10.1007/BF00235710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T., Anastasopoulos D., Becker W., Deecke L. Discrimination between trunk and head rotation; a study comparing neuronal data from the cat with human psychophysics. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1981 Aug;48(1-3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(81)90068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T., Nardi G. L., Becker W., Deecke L. The role of canal-neck interaction for the perception of horizontal trunk and head rotation. Exp Brain Res. 1983;49(2):198–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00238580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles F. A. Single unit firing patterns in the vestibular nuclei related to voluntary eye movements and passive body rotation in conscious monkeys. Brain Res. 1974 May 17;71(2-3):215–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90963-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle V. B., Lynch J. C., Georgopoulos A., Sakata H., Acuna C. Posterior parietal association cortex of the monkey: command functions for operations within extrapersonal space. J Neurophysiol. 1975 Jul;38(4):871–908. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond F. J., Bakker D. A. Anatomical organization and sensory receptor content of soft tissues surrounding upper cervical vertebrae in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1982 Jul;48(1):49–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. L., Goldberg M. E., Stanton G. B. Parietal association cortex in the primate: sensory mechanisms and behavioral modulations. J Neurophysiol. 1978 Jul;41(4):910–932. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A. M., Young J. H., Milne A. C., Schwarz D. W., Fredrickson J. M. Vestibular-neck integration in the vestibular nuclei. Brain Res. 1975 Oct 10;96(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D. W., Fredrickson J. M. Rhesus monkey vestibular cortex: a bimodal primary projection field. Science. 1971 Apr 16;172(3980):280–281. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3980.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson R. D., Robinson D. A. Signals in vestibular nucleus mediating vertical eye movements in the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1984 Jun;51(6):1121–1136. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waespe W., Henn V. Conflicting visual-vestibular stimulation and vestibular nucleus activity in alert monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1978 Oct 13;33(2):203–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00238060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waespe W., Henn V. Neuronal activity in the vestibular nuclei of the alert monkey during vestibular and optokinetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1977 Apr 21;27(5):523–538. doi: 10.1007/BF00239041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waespe W., Henn V. Vestibular nuclei activity during optokinetic after-nystagmus (OKAN) in the alert monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1977 Nov 24;30(2-3):323–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00237259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias G. L., Young L. R. Influence of combined visual and vestibular cues on human perception and control of horizontal rotation. Exp Brain Res. 1981;41(2):159–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00236605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong J. M., Bles W., Bovenkerk G. Nystagmus, gaze shift, and self-motion perception during sinusoidal head and neck rotation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1981;374:590–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb30903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]