The causal organism in Whipple's disease, a rare disorder with characteristic duodenal and jejunal changes, was first cultured in 2000.1 Although cardiac involvement is common in Whipple's, it is seldom an isolated finding.

CASE HISTORY

A man of 58, with the habit of drinking 80–100 units of alcohol a week, was referred to our hospital with heart failure. Nine months earlier his usual good health had been interrupted by an episode of acute shortness of breath without chest pain. Transthoracic echocardiography had revealed global impairment of myocardial function without a rise in troponin. He was diagnosed as having alcoholic cardiomyopathy with or without coronary artery disease and responded well to an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and a diuretic. Shortly before readmission his shortness of breath returned. He was again in cardiac failure, with peripheral oedema, hepatic congestion, and a raised jugulovenous pressure. There was no fever. Echocardiography showed a dilated left ventricle with global hypokinesis. A coronary angiogram was normal. Over the next eight weeks serial echocardiograms revealed worsening regurgitation at the mitral and aortic valves, with new mobile masses forming on both. Initially, antibiotics were withheld and he remained apyrexial. Seven sets of paired aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures yielded no bacterial growth; C-reactive protein ranged from 36 to 69 mg/L. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were introduced, but his heart failure worsened and surgical intervention was judged necessary. At operation multiple firm, pearly-yellow vegetations were apparent on the aortic and mitral valves and an abscess was found within the posterior annulus of the mitral valve. This was deroofed and swabbed copiously with iodine. St Jude Biocor bioprosthetic valves were inserted in the aortic and mitral positions. Postoperatively he was coagulopathic with high output cardiac failure. Despite blood product replacement, inotrope therapy and intraaortic balloon pump support he developed peripheral circulatory failure and died 48 hours after surgery.

Pathology

Post mortem samples were taken from heart, coronary artery, lung, liver, kidney and duodenum. Valve tissue from surgical specimens was fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. 4 μm sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, methenamine silver and elastica van Gieson. Periodic acid Schiff reaction was performed with (D-PAS) and without (PAS) prior diastase treatment. Gram and Ziehl–Neelsen stains were performed. For electron microscopy, small areas of chordae tendineae with representative yellow adhesions were fixed in 2.5% glutaradehyde, postfixed in 1.0% osmium tetroxide and embedded in TAAB epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed in a Phillips EM10 transmission electron microscope.

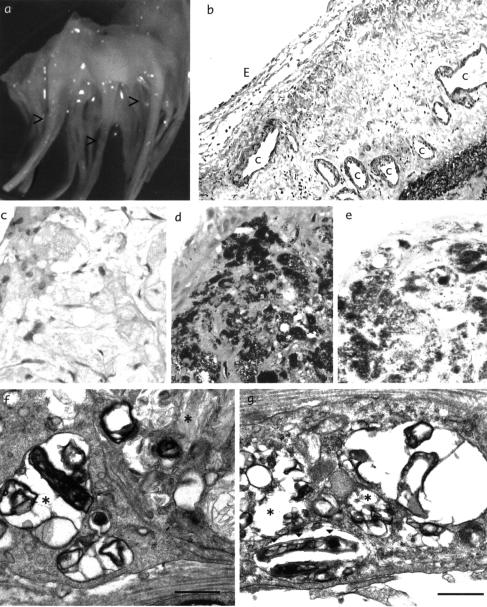

Macroscopically, small, warty, yellow elevated adhesions were present, particularly on the chordae tendineae (Figure 1a). Histological examination showed subendocardial neovascularization (Figure 1b) resembling previous descriptions of Whipple's endocarditis.2 D-PAS positive foamy macrophages, which stained with silver, were found in areas corresponding to the yellow lesions (Figure 1c,d,e). On electron microscopy, large lysosomal inclusions and multivesicular bodies were seen within macrophages, containing microbial structures in various stages of lysis (Figure 1f). Within these inclusions electron dense, rod shaped multilamellar structures were clearly visible (Figure 1g).

Figure 1.

Surgical and post mortem specimens. (a) Lesions on chordae tendineae; (b) capillaries [C] and endocardium [E] ×20; (c), (d), (e) yellow lesions stained with haematoxylin and eosin, D-PAS and methenamine silver ×40; (f), (g) electronmicrograph, showing microbial structures (*) and multilamellar inclusions (▾), bar=0.5 μm. Colour version online

At necropsy there was evidence of global ischaemic changes to the ventricles, kidneys and intestine. No conclusive macroscopic or histological evidence of Whipple's disease was seen. The intestine showed extensive autolysis but no foamy macrophages or PAS positive material. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay performed on the aortic valve tissue, targeting domain III of the 23S rDNA of Tropheryma whippelii as described elsewhere,3 was positive.

COMMENT

Whilst 20–55% of patients with a diagnosis of Whipple's disease have clinically evident cardiac manifestations,4 in very few reported cases has the initial presentation been valvular heart disease.5,6 Paravalvular abscess formation, seen in the present case, does not seem to have been reported in Whipple's endocarditis. Once diagnosed, Whipple's disease can be successfully treated with 1–2 years of agents such as cotrimoxazole.

In the past, Whipple's endocarditis was diagnosed solely on light and electron microscopy but specific PCR testing for T. whippelii DNA has been commercially available for several years, and tests on valve tissue in culture-negative endocarditis have identified occasional cases of T. whippelii infection.7 However, preoperative testing of blood or intestinal samples could give misleading results, since T. whippelii DNA has been found in symptomless individuals and in human sewage; in other words, some people may be colonized without harm. As yet, no sensitive and specific serological test exists. Therefore the diagnosis must be sought as soon as valve tissue is available from operation. Had the present patient survived without diagnosis, his endocarditis might well have returned postoperatively.

Acknowledgments

Renate Kain is supported by the National Kidney Research Fund grant SF3/2000. We thank Dr Colin Fink, Micropathology Ltd, Coventry, for performing the PCR assay.

References

- 1.Raoult D, Birg ML, La Scola B, et al. Cultivation of the bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med 2000;342: 620-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lepidi H, Fenollar F, Dumler JS, et al. Cardiac valves in patients with Whipple endocarditis: microbiological, molecular, quantitative histologic, and immunohistochemical studies of 5 patients. J Infect Dis 2004;190: 935-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinrikson HP, Dutly F, Altwegg M. Evaluation of a specific nested PCR targeting domain III of the 23S rRNA gene of Tropheryma whippelii and proposal of a classification system for its molecular variants. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38: 595-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAllister HA, Fenoglio JJ. Cardiac involvement in Whipple's disease. Circulation 1975;52: 152-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostwick DG, Bensch KG, Burke JS, et al. Whipple's disease presenting as aortic insufficiency. N Engl J Med 1981;305: 995-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkins C, Todd A, Shuman MD, Pirolo JS. Cardiac Whipple's disease without digestive symptoms. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67: 250-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grijalva M, Horvath R, Dendis M, Cerny J, Benedik J. Molecular diagnosis of culture negative endocarditis: clinical validation in a group of surgically treated patients. Heart 2003;89: 263-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]