Abstract

Purpose

Several characteristics of lymph node metastasis (LNM) as predictors of the risk of recurrence or death were examined in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). The presence of cancerous nodules as a characteristic of LNMs in PTC has not yet been reported. The objective of this study was to evaluate the use of the cancerous nodules in the lymph node (CNLN) to determine the risk of distant metastasis and survival in patients with PTC.

Methods

This retrospective observational cohort study enrolled 1408 patients with pathologically confirmed PTC without initial distant metastasis who underwent thyroidectomy and neck dissection. All patients were divided into two groups (CNLN group and Non-CNLN group) according to the presence of CNLN.

Results

Multivariate analyses showed that the presence of a special histologic variant (OR 3.31), CNLN (OR 7.13), and lateral LNM (OR 4.02) was an independent factor predictive of distant metastasis. Distant metastasis was found in 23.1% and 2.3% of patients in the CNLN and Non-CNLN group, respectively (p < 0.001). Furthermore, tumor-specific death was found in 7.7% and 0.6% of patients in the CNLN and Non-CNLN group, respectively (p < 0.001). Patients in the CNLN group had a shorter distant metastasis-free survival and overall survival than patients in the Non-CNLN group (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The presence of CNLN in patients with PTC is a novel indicator of distant metastasis and poor survival. PTC patients accompanied with CNLN should undergo more aggressive treatment and careful follow-up.

Keywords: Lymph node metastasis, Papillary thyroid cancer, Predictor, Distant metastasis, Survival

Introduction

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is one of the most common types of thyroid cancer with a favorable prognosis; the disease generally has an indolent clinical course with a 10-year disease-specific survival rate of 90% (Yamashita et al. 1998). The treatments for PTC include surgery, postoperative 131I radiotherapy, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression therapy. Regional lymph node metastases (LNM) are frequent even if the tumors are very small. LNM occurs in up to 90% of patients at the time of PTC diagnosis (Noguchi et al. 1987; Randolph et al. 2012; Kouvaraki et al. 2003; Hay et al. 2008). Because PTC often occurs with LNM, many patients have been treated with 131I radiotherapy and more aggressive TSH suppression therapy. Although LNMs are common in patients with PTC, mortality is uncommon. Among various factors that are associated with tumor-specific death, patient age, local cancer invasion, and the presence of distant metastasis are considered to be the main prognostic determinants. LNM as a prognostic factor has been plagued by controversy.

Recent studies have focused on the characteristics of the metastatic lymph nodes to improve the prediction of adverse outcomes. For example, the size of LNM is one of the most frequently studied factors. In a study by Vergez et al., the largest lymph node identified in the prophylactic central neck dissection was less than or equal to 0.5 cm in 66% of the cases and less than 1 cm in 95% of the patients (Vergez et al. 2010). Other studies also showed that patients with PTC had rates of microscopic nodal disease in up to 62% of clinical N0 (cN0) central neck compartments even though recurrence rates were only 1 to 6% if central neck dissection was not performed (Ramírez-Plaza 2015; Hughes et al. 2010). According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 7th edition) TNM classification system, patients with PTC who are ≥45-years-old are classified as stage III if the metastatic node is in the central neck and stage IVa if the microscopic LNM is identified in the lateral neck (Edge and Compton 2010). Such microscopic LNM may lead to potentially unnecessary or additional treatments. The lack of a clear prognostic indication has led to controversy in the management of cervical lymph nodes.

As mentioned in the guidelines of the American Thyroid Association (ATA), the prognostic significance of nodal metastases from PTC can be stratified based on the size and number of metastatic lymph nodes, as well as the presence of extra-nodal extension (Randolph et al. 2012; Haugen et al. 2016). Defining these characteristics can significantly influence the prognosis and the extent of treatment. To revise the prior prognostic determinants and predict a final outcome, we retrospectively analyzed the histologic findings and prognosis of patients with PTC in our hospital from 2006 to 2011. We found that the presence of cancerous nodules in the lymph node (CNLN, lymph nodes that were filled completely or nearly completely with tumor cells, regardless of the presence of a capsule, and metastatic lesions demonstrated a nodular appearance) was another characteristic related to distant metastasis and poor patient survival.

Materials and methods

Patients

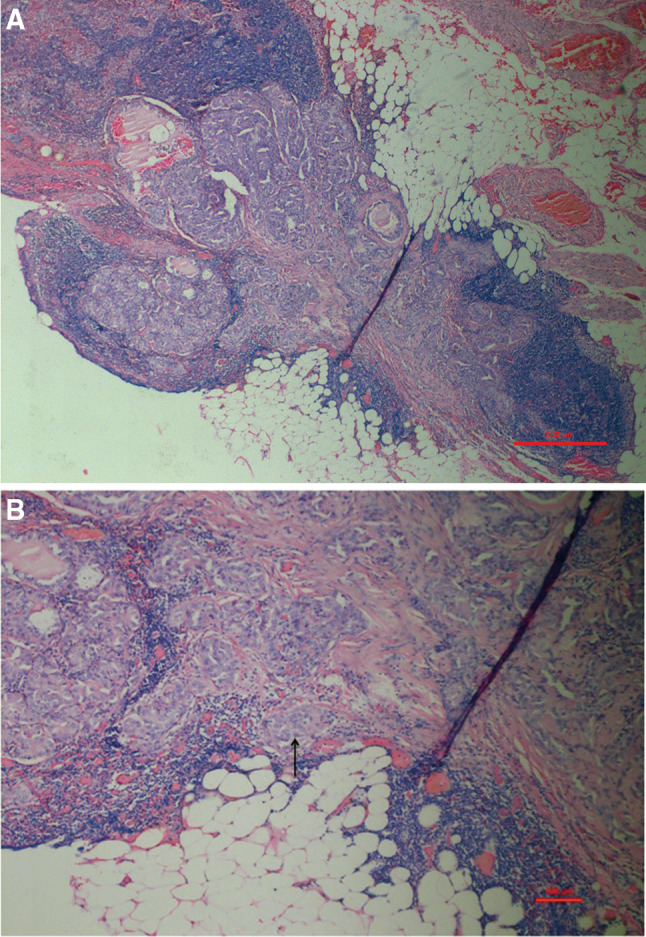

This retrospective study included patients who underwent primary treatment for PTC from January 2006 to December 2011 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China. Patients were enrolled if they met all the inclusion criteria as follows: (1) patients had undergone a total or subtotal thyroidectomy; (2) patients had undergone ipsilateral or bilateral central lymph node dissection (level VI) with or without lateral lymph node dissection; (3) patients had no preoperative evidence of distant metastasis and no other systematic cancers; (4) patients who were lost to follow-up after 5 years or had died of unrelated diseases were excluded. A total of 1408 consecutive cases of PTC were included, and 152 cases were excluded. All patients were divided into two groups (CNLN group and Non-CNLN group) according to the pathological diagnosis. The CNLN group was defined as exhibiting (1) a lymph node that was filled completely or nearly completely with tumor cells that were either present or absent in the capsule; (2) metastatic lesions that were nodular in appearance, in addition to a large number of tumor cells in the nodule and a collagenous reaction; and (3) may present with extracapsular invasion (Fig. 1a, b). In all of these cases, 65 (4.6%) were identified as having pathological changes consistent with CNLN, while 1343 (95.4%) were diagnosed as not having CNLN. In patients with CNLN, 31 (47.7%) cases exhibited more than one nodule, 25 (38.5%) had nodules located at the drainage area of the central lymph node, and the other (61.5%) cases presented nodules located in the lateral neck.

Fig. 1.

a The presence of a cancerous nodule in a lymph node. Lymph nodes were filled nearly completely by tumor cells, and metastatic lesions exhibited a nodular appearance (H & E, ×40). b A cancerous nodule in a lymph node accompanied with extracapsular invasion (arrow) (H & E, ×100)

Surgical and postsurgical treatment

All the patients underwent total or near-total thyroidectomy. The manner of lymph node dissection depended on the clinical node status, which was defined as follows. Clinical N1 (cN1) was defined as the presence of suspicious neck lymph nodes identified by preoperative physical examination, any preoperative imaging (ultrasound, CT, MR and/or PET-CT imaging), and/or gross inspection during surgery. cN0 was defined as no preoperative evidence of LNM. For the cN0 patients, only prophylactic central lymph node dissection (level VI) was performed. Ipsilateral therapeutic neck dissection would be performed (levels II, III, IV, V, and VI) in cN1 patients. The extent of primary disease and nodal status were classified according to the AJCC TNM staging system (7th edition). A total of 819 (58.42%) patients had LNM by final histopathological examination, including 561 (39.84%), 42 (2.98%), and 216 (15.34%) cases classified as N1a only, N1b only, and both N1a + N1b, respectively. Postsurgical radioiodine remnant ablation was performed according to the postoperative pathological findings. For patients in stage T3 and above and those who presented with distant metastases during the follow-up period, radioiodine remnant ablation was used; for patients with a tumor size >1 cm and a tumor confined within the thyroid or accompanied by metastasis in the cervical lymph node, selective radioiodine remnant ablation was used. In the current study, only 314 (22.3%) patients received radioactive iodine treatment because of the state’s control of radioactive materials. All patients received postoperative TSH suppression therapy.

Pathological examination

The entire specimen was obtained from the operation and examined for histological markers indicative of the presence of CNLN, vascular invasion, minimal or macroscopic extrathyroid extension, special variants of PTC, and the number of metastatic lymph nodes. All specimens were diagnosed by two pathologists independently in this study (Dr. Ke Zheng, Dr. Li Zhang).

Follow-up

Follow-up data were obtained from outpatient and inpatient admission records or correspondence or phone interviews with the patients or their family members. When a patient died, the cause of death was confirmed by the death certificate or by the hospitalization record. For patients who were followed for more than 5 years but were then lost at the last follow-up, we further confirmed the survival status of patients through the household registration system. All patients were regularly monitored by clinical and ultrasound examinations and measurements of serum thyroglobulin (Tg) concentrations. The frequency of the examinations was approximately every 3–6 months for the first 2 years and then every 6–12 months during years 3–5 and every 12–24 months after 5 years. When Tg was progressively abnormally elevated, the patient would undergo a chest CT scan, technetium-99m whole body bone scintigram,a whole body radioactive iodine scan, or F18-flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) scan. In the present study, distant metastasis was confirmed by radioactive iodine treatment,18FDG-PET scan, or pathological examination. The latest follow-up data were obtained on March 31, 2016. Of 1408 patients, distant metastasis was found in 46 (3.3%) patients; 13 (0.9%) patients died of thyroid carcinoma, and 1360 (96.6%) patients were deemed to be distant metastasis-free. The survival time was calculated as the time (in months) from diagnosis until distant metastasis or death.

Statistical analysis

Patient status and clinical and pathologic features were investigated. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. All data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS 22.0 package (SPSS 22.0 for MAC; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). The independent Student’s t test was used for continuous variables, and the Pearson Chi square test was used for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was used to examine the association with the presence of CNLN and distant metastasis. Multivariate logistic regression was performed on all variables that were significant in the univariate analysis. The results of the logistic regression analyses were reported as odds ratio (OR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and associated p values. The goodness-of-fit of each logistic regression model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Survival was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were performed using two-sided tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of PTC patients with or without CNLN

The clinical and pathological characteristics of the 1408 PTC patients enrolled in this study are shown in Table 1. CNLN was present in 65 (4.6%) PTC patients and absent in the remaining 1343 (95.4%) patients. Although there was no significant difference in patient age at the time of diagnosis, CNLN was more common in males, and the female-to-male ratio was 2.3:1 in the CNLN group vs. 3.9:1 in the Non-CNLN group (p = 0.041). Compared with the primary tumor characteristics in the Non-CNLN group, participants in the CNLN group had larger tumor sizes, were more commonly accompanied by multifocality, vascular invasion, and microscopic or macroscopic extrathyroid extension (p < 0.001). Patients with CNLN also suffered from cancer-specific distant metastasis and death more often than patients without CNLN (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with PTC with or without CNLN

| Characteristics | Total (N = 1408) | CNLN group (N = 65) | Non-CNLN group (N = 1343) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | 45.2 ± 12.2 | 44.1 ± 13.1 | 45.2 ± 12.2 | 0.449 |

| Male gender | 292 (20.7) | 20 (30.8) | 272 (20.3) | 0.041 |

| Diameter of largest primary tumor (mm) | 13.5 ± 9.1 | 17.6 ± 8.5 | 13.3 ± 9.1 | <0.001 |

| Multifocality | 392 (27.8) | 31 (47.7) | 361 (26.9) | <0.001 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 73 (5.2) | 10 (15.4) | 63 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Minimal extrathyroid extension | 170 (12.1) | 31 (47.7) | 139 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Macroscopic extrathyroid extension (T4) | 24 (1.7) | 9 (25.7) | 15 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Special variants of PTC | 180 (12.8) | 11 (16.9) | 169 (12.6) | 0.306 |

| Mean no. of metastatic lymph nodes | 2.9 ± 4.8 | 6.5 ± 5.0 | 2.7 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | 46 (3.3) | 15 (23.1) | 31 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Cancer-specific death | 13 (0.9) | 5 (7.7) | 8 (0.6) | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± SD

Special variants of PTC include the trabecular subtype, follicular variant, solid variant, diffused sclerosing variant, tall-cell variant, and columnar cell variant

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for distant metastasis

A total of 40 (87%) patients exhibited distant metastasis involving only one organ system, whereas 6 (13%) patients exhibited metastases involving more than one organ system. The lungs were the most common site of metastasis (80.4%). Univariate analysis indicated that a larger tumor size, the presence of a special histologic variant, the presence of multifocal, CNLN or lymphovascular invasion, minimal or macroscopic extrathyroid extension, the presence of LNM, and a greater number of metastatic lymph nodes were significantly associated with distant metastasis (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Multivariate analyses showed that the presence of a special histologic variant (OR 3.31; 95% CI 1.42–7.73; p = 0.006), the presence of CNLN (OR 7.13; 95% CI 2.73–18.58; p < 0.001), and the presence of lateral LNM (OR 4.02; 95% CI 1.25–12.95; p = 0.02) were independent predictive factors of distant metastasis (Table 2). We further analyzed the predictive value of CNLN in distant metastasis. As shown in Table 3, for distant metastasis, the presence of CNLN had a specificity of 96.3% and a negative predictive value of 97.7%, whereas the sensitivity and positive predictive values were low (32.6 and 23.1%, respectively). If we evaluated CNLN combined with the presence of a special histologic variant, the positive predictive value would increase to 54.5%.

Table 2.

Relationships between clinicopathologic variables and distant metastasis in patients with PTC

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age at diagnosis (≥45 years vs. <45 years) | 0.92 (0.51–1.65) | 0.776 | ||

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.36 (0.70–2.67) | 0.363 | ||

| Diameter of largest primary tumor (mm)* | – | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.71–1.49) | 0.896 |

| Histology (variant vs. classical) | 4.31 (2.32–8.02) | <0.001 | 3.31 (1.42–7.73) | 0.006 |

| Tumor foci (multifocal vs. unifocal) | 2.69 (1.49–4.86) | 0.001 | 1.45 (0.65–3.26) | 0.367 |

| Lymphovascular invasion (present vs. absent) | 4.20 (1.88–9.37) | <0.001 | 1.14 (0.37–3.54) | 0.82 |

| Minimal extrathyroid extension (present vs. absent) | 3.77 (1.99–7.14) | <0.001 | 1.79 (0.68–4.68) | 0.236 |

| Macroscopic extrathyroid extension (T4) (present vs. absent) | 8.62 (3.07–24.22) | <0.001 | 3.79 (0.93–15.46) | 0.064 |

| CNLN (present vs. absent) | 12.70 (6.45–25.01) | <0.001 | 7.13 (2.73–18.58) | <0.001 |

| Metastatic lymph node (present vs. absent) | 2.35 (1.18–4.66) | 0.012 | 0.68 (0.16–2.85) | 0.597 |

| No. of metastatic lymph nodes* | – | 0.003 | 1.09 (1.0-1.18) | 0.052 |

| Central LNM (present vs. absent) | 1.27 (0.70–2.32) | 0.431 | ||

| Lateral LNM (present vs. absent) | 9.33 (5.0-17.40) | <0.001 | 4.02 (1.25–12.95) | 0.02 |

Histology variant of PTC, including the trabecular subtype, follicular variant, solid variant, diffused sclerosing variant, tall-cell variant, and columnar cell variant

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

*Continuous variables were analyzed with the independent Student’s t test, and categorical variables were analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test

Table 3.

Predictive Values of CNLN with distant metastasis in patients with PTC (%)

| Variable | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNLN only | 32.6 | 96.3 | 23.1 | 97.7 |

| CNLN with special variant | 13 | 99.6 | 54.5 | 97.1 |

Special variant of PTC, including the trabecular subtype, follicular variant, solid variant, diffused sclerosing variant, tall-cell variant, and columnar cell variant

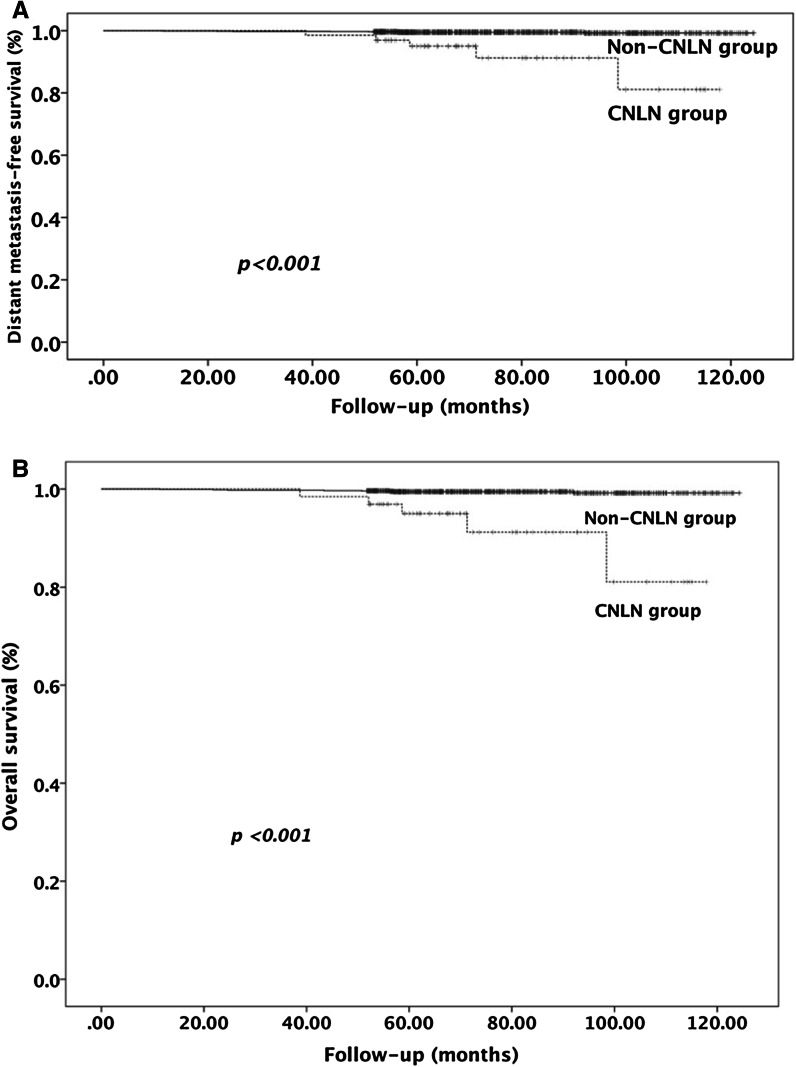

CNLN and survival

The mean follow-up period for all patients was 78.8 ± 19.8 months (range 11 to 123 months). Of 1408 patients, distant metastasis was found in 46 (3.3%) patients, 13 (0.9%) patients died of thyroid carcinoma (11 died of distant metastasis and 2 died of tumor-specific respiratory asphyxia), and 1360 (96.6%) patients were deemed to be free of distant metastasisand tumor-specific death. A total of 15 (23.1%) patients in the CNLN group presented with distant metastasis, which was present in 31 (2.3%) patients in the Non-CNLN group (p < 0.001). Tumor-specific death occurred in 5 patients in the CNLN group (7.7%) and in 8 patients (0.6%) in the Non-CNLN group (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test were employed to explore the relationship between CNLN, distant metastasis-free survival, and overall survival (Fig. 2a, b). Patients in the CNLN group had a shorter distant metastasis-free survival than patients in the Non-CNLN group: 93.8 months (95% CI 83.0–104.7) versus 121.8 months (95% CI 120.9–122.7). The 10-year distant metastasis-free survival was 74% (95% CI, 62%–86%) versus 97.7% (95% CI, 96.9%–98.5%) in patients with and without CNLN, respectively (p < 0.001). In addition, differences in overall survival were identified between patients in the CNLN group and the Non-CNLN group. The mean overall survival was 110.8 months (95% CI 104.8–116.8) in the CNLN group vs. 123.9 months (95% CI 123.5–124.3) in the Non-CNLN group (p < 0.001). The 10-year overall survival of CNLN patients was 81.1% (95% CI, 71.1%–91.1%) compared with 99.2% (95% CI, 98.6%–99.8%) in the Non-CNLN patients (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

a The 10-year distant metastasis-free survival was 74% (95% CI, 62–86%) in CNLN patients and 97.7% (95% CI, 96.9–98.5%) in the Non-CNLN patients (p < 0.001). b The 10-year overall survival was 81.1% (95% CI, 71.1–91.1%) in CNLN patients and 99.2% (95% CI, 98.6–99.8%) in the non-CNLN patients (p < 0.001)

Discussion

Data from this study demonstrated the novel finding, not previously reported, the presence of CNLN in patients with PTC is an indicator of distant metastasis and poor survival. Because of PTC is one of the most common types of thyroid tumors and is usually associated with a good prognosis, traditionally, PTC nodal metastases have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence but exhibit little influence on survival (Baek et al. 2010). Several well-described systems are routinely used to assess risk in patients with PTC, including AMES (Age, Metastasis, Extent, Size), AGES (Age, Grade, Extent, Size), and MACIS (Metastasis, Age, Completeness of surgery, Invasiveness, Size), did not take into account nodal status (Ramírez-Plaza 2015). Recent studies reported that lymph node metastases larger than 3 cm in size, the presence of extranodal extension, or metastasis present in more than five lymph nodes were significantly correlated with the recurrence and persistence of thyroid cancer and reduced patient survival (Sugitani et al. 2004; Yamashita et al. 1997; Machens et al. 2002; Ito et al. 2007). Therefore, both the AJCC and ATA risk systems used the characteristics of LNM (e.g., the size of the largest lymph node, the number of metastatic lymph nodes, and the presence of extranodal extension) as predictors for the risk of recurrence or death. However, the roles of these variables as independent predictors of disease-specific mortality remain to be defined (Randolph et al. 2012; Haugen et al. 2016; Vas Nunes et al. 2013). Defining these factors could significantly influence patient prognosis and the extent of treatment. In our study, we demonstrated that CNLN was another characteristic related to distant metastasis and poor survival.

CNLN as a characteristic of metastatic lymph nodes in PTC has not been previously reported. The current study showed that CNLN was more commonly associated with male gender, larger tumor size, multifocality, vascular invasion, and microscopic or macroscopic extrathyroid extension. Many of these features have been confirmed as prognostic markers (Akslen et al. 1992; Lundgren et al. 2006). Patients in the CNLN group appeared to have a more aggressive form of the disease than those in the Non-CNLN group. Obviously, CNLN is linked to the presence of local aggressive PTC, which exhibits an elevated risk of recurrence and distant metastasis (Lin et al. 1999; Akkas et al. 2014). In addition, it is noteworthy that CNLN is not the product of a particular subtype of PTC.

Distant metastasis is one of the most important prognostic factors in PTC (Lang et al. 2013). In the present study, patients with distant metastasis had a poor prognosis. Eleven (84.6%) patients who suffered tumor-specific death exhibited distant metastasis. Furthermore, the multivariate analysis showed that the presence of a special histologic variant (OR 3.31), the presence of CNLN (OR 7.13), and the presence of lateral LNM (OR 4.02) were independent predictive factors for distant metastasis. In previous studies, the presence of a special histologic variant or a lateral LNM have been confirmed to be independent risk factors for distant metastasis. Therefore, the TNM system assigned an increased risk of metastatic disease for lateral neck LNs (N1b) compared with that of central neck LNs (N1a) (Edge and Compton 2010). In addition, several special histological subtypes of PTC, such as trabecular subtype, diffuse (or multinodular) follicular variants, solid variants, diffused sclerosing variants, and columnar cell variants, among others, appear to be more frequently associated with distant metastasis, are present in approximately 15% of cases, and indicate a slightly higher mortality rate (Mizukami et al. 1992; Regalbuto et al. 2011; Nikiforov et al. 2001; Morris et al. 2010). Although the presence of lateral LNM or special histologic variants has been confirmed to be associated with distant metastasis in previous studies, the presence of CNLN had the largest OR value among the three independent factors that had not yet been previously reported. Our data strongly demonstrated that presence of CNLN in patients with PTC were closely associated with distant metastasis and poor prognosis. We also found that the presence of CNLN had a specificity of 96.3% and a negative predictive value of 97.7%, whereas the sensitivity and positive predictive values were low (32.6 and 23.1%, respectively), supporting the effectiveness and applicability of CNLN to predict distant metastasis. These findings are similar to those obtained in a study of the correlation between the number of LNMs and lung metastasis in patients with PTC (Machens and Dralle 2012). For distant metastasis, the presence of more than 20 LNMs had a specificity of 90.8% and a negative predictive value of 92.7%, whereas the sensitivity and positive predictive values were low (27.6 and 22.9%, respectively). If the presence of CNLN and special histologic variants were examined together, the positive predictive value would increase to 54.5%. This method will have good prospects for application.

Compared with other characteristics of LNM that can significantly influence prognosis, CNLN as a categorical variable has demonstrated some advantages. First, because the number of LNMs is a continuous variable, it is inevitably affected by the meticulous work of the surgeon and the pathologist. The cut-off value varies in existing studies, and the number of LNMs ranges from 5 to 20 (Sugitani et al. 2004; Machens and Dralle 2012; Leboulleux et al. 2005). In the current study, we only confirmed that the location of LNM based on the TNM staging system was more useful than the number of LNMs for estimating the risk of distant metastasis in PTC. Experience from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database also showed that lateral LNM increased the risk of death from PTC (Ba et al. 2012). Regarding extracapsular invasion in LNM, we also found that CNLN was present with extracapsular invasion in approximately 30% of cases. In the CNLN group, the incidence of distant metastasis and tumor-specific survival did not differ according to the presence or absence of extracapsular invasion (data not shown), implying that the prognostic value of CNLN was higher than the prognostic value of extranodal extension. According to previous work by Spires, there were no statistically significant differences in regional recurrence, distant metastases, death from cancer, or recurrence-free survival between patients with or without extracapsular invasion (Spires et al. 1989). Subsequently, Asanuma et al. demonstrated that macroscopic extranodal invasion predicted a high incidence of tumor recurrence, but it was not an independent prognostic factor (Asanuma et al. 2001). Recently, Ito et al. classified all cases of PTC into three categories based on the degree of nodal extension. The authors demonstrated that the presence of nodal extension reflected the biologically aggressive behavior of PTC and was of prognostic value, especially in terms of the cause-specific survival of patients (Ito et al. 2007). Therefore, simple application of extranodal extension to predict the prognosis is still a certain defect.

This study has several limitations. First, a large number of patients who did not undergo lymph node dissection or were lost to follow-up after less than 5 years were excluded from the study, indicating possible selection bias associated with all retrospective analyses. Additionally, the current study only focuses on distant metastasis and survival, and data for local disease recurrence, or disease-free survival were not presented, all of which may be associated with CNLN. Additional prospective studies are needed to exclude potential negative influences on these results. Finally, we did not present the immunohistochemical and molecular features of CNLN, so that we were temporarily unable to conduct research at the protein and molecular levels. These limitations will be addressed in subsequent work.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that CNLN occurs as a consequence of local aggressive PTC. The presence of CNLN in patients with PTC is a novel indicator of distant metastasis and poor survival. Due to the presence of CNLN in patients with PTC, more aggressive treatment and careful follow-up should be considered.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This study was funded by the Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fujian, P.R.C, Youth Research Project of Fujian Provincial Department of Health (2014-1-61) and Fujian Province Middle and Young Teacher Education Science and Technology Project Funding (JA14146).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Ling Chen and Youzhi Zhu contributed equally to this paper.

References

- Akkas BE, Demirel BB, Vural GU (2014) Prognostic factors affecting disease-specific survival in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic differentiated thyroid carcinoma detected by positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Thyroid 24:287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akslen LA, Myking AO, Salvesen H, Varhaug JE (1992) Prognostic importance of various clinicopathological features in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 29A:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Kusama R, Maruyama M, Fujimori M, Amano J (2001) Macroscopic extranodal invasion is a risk factor for tumor recurrence in papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer Lett 164:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ba VAS, Sessions RB, Lentsch EJ (2012) Cervical lymph node metastasis and papillary thyroid carcinoma: Does the compartment involved affect survival? Experience from the SEER database [J]. J Surg Oncol 106(4):357–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S-K, Jung K-Y, Kang S-M, Kwon S-Y, Woo J-S, Cho S-H, Chung EJ (2010) Clinical risk factors associated with cervical lymph node recurrence in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 20:147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge SB, Compton CC (2010) The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 17:1471–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L (2016) 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the american thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ID, Hutchinson ME, Gonzalez-Losada T, McIver B, Reinalda ME, Grant CS, Thompson GB, Sebo TJ, Goellner JR (2008) Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 900 cases observed in a 60-year period. Surgery 144:980–987 (discussion 987–988) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DT, White ML, Miller BS, Gauger PG, Burney RE, Doherty GM (2010) Influence of prophylactic central lymph node dissection on postoperative thyroglobulin levels and radioiodine treatment in papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery 148:1100–1106 (discussion 1006–1007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Hirokawa M, Jikuzono T, Higashiyama T, Takamura Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, Matsuzuka F, Kuma K, Miyauchi A (2007) Extranodal tumor extension to adjacent organs predicts a worse cause-specific survival in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 31:1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvaraki MA, Shapiro SE, Fornage BD, Edeiken-Monro BS, Sherman SI, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Lee JE, Evans DB (2003) Role of preoperative ultrasonography in the surgical management of patients with thyroid cancer. Surgery 134:946–954 (discussion 954–955) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang BH, Wong KP, Cheung CY, Wan KY, Lo C-Y (2013) Evaluating the prognostic factors associated with cancer-specific survival of differentiated thyroid carcinoma presenting with distant metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 20:1329–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboulleux S, Rubino C, Baudin E, Caillou B, Hartl DM, Bidart J, Travagli J, Schlumberger M (2005) Prognostic factors for persistent or recurrent disease of papillary thyroid carcinoma with neck lymph node metastases and/or tumor extension beyond the thyroid capsule at initial diagnosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5723–5729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JD, Chao TC, Weng HF, Ho YS (1999) Prognostic variables of papillary thyroid carcinomas with local invasion. Endocr J 46:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren CI, Hall P, Dickman PW, Zedenius J (2006) Clinically significant prognostic factors for differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a population-based, nested case-control study. Cancer 106:524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machens A, Dralle H (2012) Correlation between the number of lymph node metastases and lung metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:4375–4382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machens A, Hinze R, Thomusch O, Dralle H (2002) Pattern of nodal metastasis for primary and reoperative thyroid cancer. World J Surg 26:22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y, Noguchi M, Michigishi T, Nonomura A, Hashimoto T, Otakes S, Nakamura S, Matsubara F (1992) Papillary thyroid carcinoma in Kanazawa, Japan: prognostic significance of histological subtypes. Histopathology 20:243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris LG, Shaha AR, Tuttle RM, Sikora AG, Ganly I (2010) Tall-cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a matched-pair analysis of survival. Thyroid 20:153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov YE, Erickson LA, Nikiforova MN, Caudill CM, Lloyd RV (2001) Solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: incidence, clinical-pathologic characteristics, molecular analysis, and biologic behavior. Am J Surg Pathol 25:1478–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi M, Yamada H, Ohta N, Ishida T, Tajiri K, Fujii H, Miyazaki I (1987) Regional lymph node metastases in well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Int Surg 72:100–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Plaza CP (2015) Central neck compartment dissection in papillary thyroid carcinoma: an update. World J Surg Proced 5:177–186 [Google Scholar]

- Randolph GW, Duh Q-Y, Heller KS, LiVolsi VA, Mandel SJ, Steward DL, Tufano RP, Tuttle RM, American Thyroid Association Surgical Affairs Committee’s Taskforce on Thyroid Cancer Nodal Surgery (2012) The prognostic significance of nodal metastases from papillary thyroid carcinoma can be stratified based on the size and number of metastatic lymph nodes, as well as the presence of extranodal extension. Thyroid 22:1144–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalbuto C, Malandrino P, Tumminia A, Le MR, Vigneri R, Pezzino V (2011) A diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: clinical and pathologic features and outcomes of 34 consecutive cases. Thyroid 21:383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires JR, Robbins KT, Luna MA, Byers RM (1989) Metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: the significance of extranodal extension. Head Neck 11:242–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugitani I, Kasai N, Fujimoto Y, Yanagisawa A (2004) A novel classification system for patients with PTC: addition of the new variables of large (3 cm or greater) nodal metastases and reclassification during the follow-up period. Surgery 135:139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vas Nunes JH, Clark JR, Gao K, Chua E, Campbell P, Niles N, Gargya A, Elliott MS (2013) Prognostic implications of lymph Node yield and lymph Node ratio in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 23:811–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergez S, Sarini J, Percodani J, Serrano E, Caron P (2010) Lymph node management in clinically node-negative patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 36:777–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Noguchi S, Murakami N, Kawamoto H, Watanabe S (1997) Extracapsular invasion of lymph node metastasis is an indicator of distant metastasis and poor prognosis in patients with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Cancer 80:2268–2272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Noguchi S, Yamashita H, Murakami N, Watanabe S, Uchino S, Kawamoto H, Toda M, Nakayama I (1998) Changing trends and prognoses for patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Arch Surg 133:1058–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]