Abstract

In most human populations, the ability to digest lactose contained in milk usually disappears in childhood, but in European-derived populations, lactase activity frequently persists into adulthood (Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). It has been suggested (Cavalli-Sforza 1973; Hollox et al. 2001; Enattah et al. 2002; Poulter et al. 2003) that a selective advantage based on additional nutrition from dairy explains these genetically determined population differences (Simoons 1970; Kretchmer 1971; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988; Enattah et al. 2002), but formal population-genetics–based evidence of selection has not yet been provided. To assess the population-genetics evidence for selection, we typed 101 single-nucleotide polymorphisms covering 3.2 Mb around the lactase gene. In northern European–derived populations, two alleles that are tightly associated with lactase persistence (Enattah et al. 2002) uniquely mark a common (∼77%) haplotype that extends largely undisrupted for >1 Mb. We provide two new lines of genetic evidence that this long, common haplotype arose rapidly due to recent selection: (1) by use of the traditional FST measure and a novel test based on pexcess, we demonstrate large frequency differences among populations for the persistence-associated markers and for flanking markers throughout the haplotype, and (2) we show that the haplotype is unusually long, given its high frequency—a hallmark of recent selection. We estimate that strong selection occurred within the past 5,000–10,000 years, consistent with an advantage to lactase persistence in the setting of dairy farming; the signals of selection we observe are among the strongest yet seen for any gene in the genome.

Introduction

Genes that have experienced recent positive selection offer a window into the evolutionary forces that shaped recent human history. For example, signatures of recent selection for resistance to malaria have been demonstrated around the HbS allele in the β-globin gene HBB (MIM 141900) (Pagnier et al. 1984), the A− and Med alleles in G6PD (MIM 305900) (Tishkoff et al. 2001), the *O allele of the Duffy gene FY (MIM 110700) (Hamblin et al. 2002), and a promoter variant in the CD40 ligand gene TNFSF5 (MIM 300386) (Sabeti et al. 2002). Other genes for which genetic data support a recent selective event include CKR5 (MIM 601373) (Stephens et al. 1998), HFE (MIM 235200) (Toomajian et al. 2003), ADH1B (MIM 103720) (Osier et al. 2002), and possibly CFTR (MIM 602421) (Wiuf 2001 and references therein); the particular evolutionary advantage in these cases is less clear. Many of the selected alleles also contribute to or cause disease, indicating that identification of genes under selection may have significant consequences for medical genetics. Furthermore, once such genes have been definitively identified, characterizing the signatures of selection at these genes will guide the development of tools to search for other genes under selection.

One of the genes most frequently proposed to have experienced recent positive selection is LCT (MIM 603202), which encodes the enzyme lactase-phlorizin hydrolase. The epidemiologic data in favor of selection are quite strong: the ability to use this enzyme to digest lactose during adulthood varies dramatically across worldwide populations, with particularly high rates among northern Europeans (Bayless and Rosensweig 1966; Simoons 1969; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). Furthermore, persistence of lactase activity into adulthood is genetically determined (Simoons 1970; Kretchmer 1971; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988; Enattah et al. 2002), and the geographic distribution of lactase persistence matches the distribution of dairy farming (Simoons 1969; Kretchmer 1971; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). Because of these features, Cavalli-Sforza (1973) and others (Simoons 1970; Flatz 1987; Hollox et al. 2001; Poulter et al. 2003) proposed that the high rate of lactase persistence in European populations is explained by positive selection resulting from increased nutrition from dairy, the only dietary source of lactose. Despite these compelling epidemiologic data, neither formal population-genetics–based evidence of selection nor an estimate of the timing and magnitude of positive selection has been provided by analyzing genetic data at the LCT locus. In addition, many non-European populations show high rates of lactase persistence, raising questions about whether a single allele arose once and is shared by all lactase-persistent individuals or whether different alleles have arisen in human history.

Recently, new tools to study selection at LCT have become available. In particular, Enattah et al. (2002) demonstrated that two polymorphisms upstream of LCT are tightly associated with lactase persistence. In that study, the persistence-associated alleles were found primarily on a single 250-kb microsatellite haplotype in the Finnish population. By use of 18 SNPs spanning 1 Mb, Swallow and colleagues also recently reported a long haplotype around these alleles (Poulter et al. 2003). However, the mere presence of a long haplotype, although consistent with selection, does not by itself constitute a signature of a selective event (Sabeti et al. 2002).

A variety of genetic signatures of positive selection have been described (reviewed in Bamshad and Wooding 2003). These include an excess of rare variants (indicating a selective sweep followed by the accumulation of new, rare mutations), large allele-frequency differences among populations (indicating differential effects of selection that cause alleles to rise dramatically in frequency in some but not all of the populations), or a common haplotype that remains intact over unusually long distances (indicating an allele that rose rapidly to high frequency before recombination could disrupt the haplotype on which the allele lies). The last two signatures are particularly appealing because they can be detected by genotyping common polymorphisms in one or more populations and may have better power for identifying recent positive selection (Sabeti et al. 2002). Large differences in allele frequencies between populations have traditionally been detected by use of the population-genetics measure FST (e.g., Akey et al. 2002), whereas demonstration that a common haplotype is unexpectedly long requires application of the recently described long-range haplotype test (Sabeti et al. 2002).

In this study, we analyze genotypes for >100 SNPs in multiple populations, and we demonstrate two striking signatures of selection at the LCT gene. First, SNPs near LCT show large differences in allele frequencies among populations, demonstrated not only with the traditional FST measure but also with a more informative metric, pexcess. In addition, we show that the long (1 Mb) haplotype carrying the persistence-associated alleles is much longer and more common than would be expected in the absence of selection. We are also able to estimate from these genetic data the time period during which selection occurred, and we show that the selective pressure at LCT was comparable to the strongest selection yet documented in the genome.

Subjects and Methods

DNA Samples

DNA samples for European American, African American, and East Asian populations were obtained from the Coriell Institute (Coriell Institute for Medical Research Web site); a complete list of these samples and geographic origins is given in table A1 (online only). The Scandinavian population, which has been described elsewhere (Altshuler et al. 2000), is a subset of 379 normal glucose-tolerant trios from Finland and Sweden, and the samples we typed represent 360 independent chromosomes. The remaining populations listed in table 1 have also been described elsewhere (Rosenberg et al. 2002). This project was approved by the appropriate local institutional review boards, and subjects gave informed consent.

Table 1.

Frequencies in Different Populations of Two Alleles Associated with Lactase Persistence[Note]

|

Frequency (%) for |

|||

| PopulationGroup (Regionand/or Country) | No. of Chromosomes | −13910T | −22018A |

| European American | 48 | 77.2 | 77.1 |

| African American | 100 | 14.0 | 13.3 |

| East Asian | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Yoruba (Nigeria) | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Bantu Northeast (Kenya) | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| San (Namibia) | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Bantu (South Africa) | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Mozabite (Mzab, Algeria) | 60 | 21.7 | 21.7 |

| Bedouin (Negev, Israel) | 98 | 3.1 | 4.1 |

| Druze (Carmel, Israel) | 96 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Palestinian (Central Israel) | 102 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Brahui (Pakistan) | 50 | 34.0 | 38.0 |

| Balochi (Pakistan) | 50 | 36.0 | 42.0 |

| Hazara (Pakistan) | 50 | 8.0 | 12.0 |

| Makrani (Pakistan) | 50 | 34.0 | 36.0 |

| Sindhi (Pakistan) | 50 | 32.0 | 30.0 |

| Pathan (Pakistan) | 50 | 30.0 | 32.0 |

| Kalash (Pakistan) | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Burusho (Pakistan) | 50 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Han (China) | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| Tujia (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Yizu (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Miaozu (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Oroqen (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Daur (China) | 20 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Mongola (China) | 20 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Hezhen (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Xibo (China) | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Uygur (China) | 20 | 5.0 | 10.0 |

| Dai (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Lahu (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| She (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Naxi (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Tu (China) | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Yakut (Siberia) | 50 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Japanese (Japan) | 62 | 0 | 0 |

| Cambodian (Cambodia) | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Papuan (New Guinea) | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanesiana (Bougainville) | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| French (France) | 58 | 43.1 | 44.8 |

| French Basque (France) | 48 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Sardinian (Italy) | 56 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Tuscan (Italy) | 16 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| North Italian (Bergamo, Italy) | 28 | 35.7 | 35.7 |

| Orcadian (Orkney Islands) | 32 | 68.8 | 68.8 |

| Adygei (Russian Caucasus) | 34 | 11.8 | 11.8 |

| Russian (Russia) | 50 | 24.0 | 24.0 |

| Swedish and Finnish (Scandinavia) | 360 | 81.5 | ND |

| Pima (Mexico) | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Maya (Mexico) | 50 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Colombian (Colombia) | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Karitiana (Brazil) | 48 | 0 | 0 |

| Surui (Brazil) | 42 | 0 | 0 |

Note.— The European American, African American, and East Asian samples are from the Coriell Institute Cell Repository (Coriell Institute for Medical Research Web site). The Scandinavian (Altshuler et al. 2000) and the remaining (Rosenberg et al. 2002) populations have been described elsewhere. ND = not done.

Non-Austronesian.

Selection and Genotyping of SNPs

SNPs were selected from dbSNP (dbSNP Home Page), preferentially choosing the SNP Consortium (TSC) and BAC overlap SNPs (submitter handles: TSC, SC_JCM, and KWOK) and genotyping SNPs at a greater density closer to the LCT gene. In addition, we intentionally genotyped the two SNPs reported to be associated with LCT persistence (Enattah et al. 2002). A complete list is given in table A2 (online only). SNPs were genotyped by use of the mass-spectrometry–based MassArray platform provided by Sequenom, implemented as described elsewhere (Gabriel et al. 2002). Primers were designed by use of Spectrodesigner software (Sequenom), and sequences are available on request.

Statistical Analysis

FST was calculated as described by Akey et al. (2002), with Nei’s correction for sample size (Nei and Chesser 1983). To generate a genomewide distribution for FST and pexcess, allele frequencies at markers throughout the genome were downloaded from the SNP Consortium (TSC) Web site, by use of data from the Whitehead Institute Center for Genome Research (WICGR), Celera, Motorola, and Orchid. We excluded data from pooled samples, since the FST distribution was different for pooled data (Akey et al. 2002 and data not shown). In total, data from 28,440 markers were used to generate a genomewide FST distribution. To compare the FST at markers around LCT with the genomewide distribution, we applied the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Rosner 1982), limiting our analysis to markers separated by at least 20 kb to minimize correlation between markers. To eliminate artifactual effects at the lower end of the FST distribution (which can be due, in part, to the correction for sample size), we treated all FST values below the population mean as ties. Applying this test to the markers around LCT yields a P value of .002. However, because we cannot fully correct for the correlation between markers, this P value may overestimate the significance of the excess markers with high FST values.

To understand the rationale for using the pexcess statistic, consider the scenario where positive selection rapidly introduces a single haplotype at frequency h into a population. Under the model of strong selection, a particular long-range haplotype will rapidly rise from a single copy (frequency near 0) to a frequency of h in the selected population. Consider now a marker within the long-range haplotype with an allele of frequency p prior to the selective event. If there has been little opportunity for recombination, nearly all copies of the selected haplotype will carry the same allele at this marker. For the allele that lies on the selected haplotype, the allele frequency will increase to p1=p(1-h)+h after selection; for an allele that does not lie on the selected haplotype, the allele frequency will decrease to p1=p(1-h). Solving for h, h=(p1-p)/(1-p) if p1>p and h=(p-p1)/p if p > p1. This is algebraically identical to pexcess (Hastbacka et al. 1994); here, p1 is the allele frequency in the population under consideration, and p is the ancestral allele frequency, which we estimate by the average allele frequency in the populations that have not experienced selection (in this case, the East Asian and African American populations). To maximize the chance that the variant predates the selective event (essential for using pexcess to estimate h), we only calculate pexcess for polymorphisms in which the allele frequencies in all populations are between 10% and 90%. Similar results were obtained whether or not we corrected the allele frequencies in African Americans for the estimated 21% European admixture (Parra et al. 1998). Of the markers from the SNP Consortium (TSC) Web site, 13,696 have allele frequencies between 10% and 90% for all three populations, and these were used for calculating the genomewide characteristics of pexcess. For comparison, we identified 952 regions with at least 5 markers spanning 50 kb–100 kb. We found that none of these 952 regions contains runs of ⩾5 consecutive markers that span at least 50 kb and have pexcess values above the 90th percentile; the LCT region has 16 consecutive markers spanning 800 kb with pexcess values above the 95th percentile.

The long-range haplotype test, the calculation of relative extended haplotype homozygosity (REHH), and the assessment of the significance of REHH by use of simulations were performed as described elsewhere (Sabeti et al. 2002). In brief, a core region was defined as a block of linkage disequilibrium with little evidence of recombination (Gabriel et al. 2002). The genotype data was converted to inferred, fully phased haplotype data, and, within the core region, each common haplotype (>5% frequency) was analyzed separately. At each marker, a chromosome was considered intact if, from the core through that marker, the chromosome was identical to all other intact chromosomes carrying the same core haplotype. For LCT, the core region was chosen to contain the persistence-associated markers. For the simulations, cores and genotypes extending outward from the cores were generated as described elsewhere (Sabeti et al. 2002). The empirical P value for the 5′ markers was .012. For the 3′ markers, 10,000 simulations generated ∼25,000 core haplotypes, of which ∼2,500 had a frequency similar to that of the LCT core; none of these had an REHH near that seen for LCT (empirical P < .0004). To better estimate the P value for the 3′ markers, the REHH distribution from the simulated data was log-transformed to achieve normality, and the mean, median, and SD were used to estimate P values for the actual REHH value observed in LCT. The estimation of dates was performed according to methods described elsewhere (Reich and Goldstein 1998; Stephens et al. 1998).

For these analyses, fully phased haplotype data were required. We used two phasing programs: PHASE, a Bayesian method for phasing diploid genotype data (Stephens and Donnelly 2003; PHASE Web site), and also a similar program (wphase) that we developed for this purpose. Similar results were obtained from the two phasing algorithms. The mathematical models underlying the two programs are similar, but PHASE performs a Markov Chain–Monte Carlo procedure, whereas wphase carries out a hill climb, (approximately) maximizing the likelihood. We estimated REHH and dates at distances on either side of the core region, where approximately one recombination per chromosome had occurred on the persistence-associated haplotype (that is, ∼1/e chromosomes carrying the persistence-associated haplotype remained unrecombined).

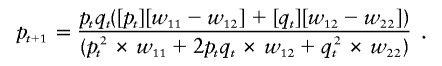

We estimated the coefficient of selection, s, by applying a formula (Hartl and Clark 1997) that relates the frequency in generation t+1(pt+1) to the frequency in generation t(pt):

|

In this formula, qt=1-pt,w11 is the relative fitness of individuals homozygous for the selected allele, w12 is the relative fitness of heterozygous individuals, and w22 is the relative fitness of individuals homozygous for the unselected allele. We assumed a dominant model for lactase persistence—that is, w11=w12=1 and w22=1-s. We also assumed the initial frequency p0 to be between 1/1,000 and 1/10,000 (corresponding to a new mutation in a population with an effective size between 500 and 5,000; larger population sizes yield even higher coefficients of selection). Starting from these initial frequencies, we calculated values of w22 that would yield a frequency of p = 0.77 after 2,188–20,650 years of selective pressure for the United States population and 1,625–3,188 years for the Scandinavian population, assuming 25 years/generation.

Results

To examine the evidence for selection, we began by genotyping the two SNPs that were recently reported to be very tightly associated with lactase persistence (Enattah et al. 2002): rs4988235 (−13910C→T) and rs182549 (−22018G→A). We determined the frequencies of the persistence-associated alleles (T and A, respectively) in three populations for which many thousands of markers have been genotyped (European Americans, African Americans, and East Asians), thereby permitting comparison of our results to a genomewide background distribution (Akey et al. 2002). The persistence-associated alleles occur with a frequency of 77% in European Americans, 13% and 14% in African Americans, and 0% in East Asians (table 1), broadly consistent with the rates of lactase persistence in these populations (Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). Large differences in allele frequencies across populations, such as we observe at these markers, are suggestive of selective pressure that differed among the populations (Lewontin and Krakauer 1973; Bowcock et al. 1991; Akey et al. 2002). The unusually large magnitude of the population frequency differences for these two markers is reflected in their values of FST, a traditional measure of population differentiation—the FST values (0.53 for both markers) exceed 99.9% of the FST values from a genomewide set of >28,000 SNPs (see the “Subjects and Methods” section). We also genotyped these two associated SNPs in a more diverse set of samples (Altshuler et al. 2000; Rosenberg et al. 2002); the frequencies of the persistence-associated alleles were much lower in southern European than in northern European or Basque populations, and the persistence-associated alleles were rare or absent in almost all non-European–derived populations tested, except Algerians and Pakistanis (table 1). The wide range of allele frequencies among European populations is consistent with selective pressure that postdates the colonization of Europe, resulting in different prevalences of lactase-persistence alleles in northern and southern European populations.

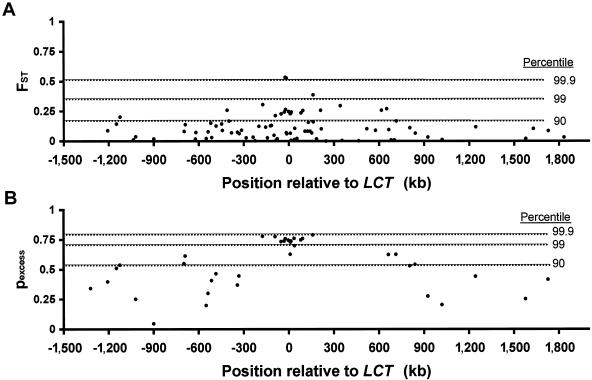

To extend these results, we genotyped an additional 99 markers in 3.2 Mb flanking the LCT locus, again looking for high degrees of population differentiation. In response to strong positive selection, a selected allele rises rapidly in frequency. The frequency of the haplotype on which the allele occurs will increase correspondingly, because there is insufficient time for recombination to disrupt the haplotype while it becomes more common. Thus, allele frequencies at flanking markers on the haplotype will be altered. To measure this effect, we used two metrics of allele-frequency differences: the traditional FST and a newer metric, pexcess. FST has limited utility when the flanking allele on the selected haplotype was already fairly common prior to selection, because, in this case, the FST value will be quite low; thus, only a fraction of flanking markers are expected to show elevated FST values within a region of selection. Consistent with this expectation, there was an excess of high FST values among the 99 markers, but FST values varied widely from marker to marker (fig. 1a; see the “Subjects and Methods” section for additional details). The excess elevation of FST is predominantly derived from markers located in the vicinity of the LCT gene (fig. 1a), with allele frequencies that are generally different in Europeans than in the other two populations (table A2 [online only]). This elevated FST in markers flanking LCT confirms the signal of selection seen with the −13910C→T and −22018G→A variants. However, as expected, only some of the markers near LCT have elevated FST values. Accordingly, we sought an alternative measure of population differentiation that would reveal a more consistent signal in the vicinity of a selected allele.

Figure 1.

Elevation in (a) FST and (b) pexcess at multiple SNPs in a 3.2-Mb region around the LCT gene. Position in kb relative to the start of transcription of LCT is on the X-axis. The 90th, 99th, and 99.9th percentiles for FST and pexcess are indicated by dashed lines and are based on 28,440 and 13,696 markers, respectively, throughout the genome (see the “Subjects and Methods” section).

We chose to study the pexcess statistic, which has previously been used to localize disease-causing alleles in founder populations and is a measure of differences in haplotype frequencies across long distances (Hastbacka et al. 1994). pexcess is also equivalent to the measure of linkage disequilibrium, δ (Devlin and Risch 1995). If a single haplotype differs in frequency across a long region, pexcess will be elevated and relatively constant across multiple markers within that region, with values approximately equal to the increase in frequency of the haplotype (see the “Subjects and Methods” section for details). We observed a consistent, marked elevation of pexcess in the LCT region: 17 consecutive markers in a region spanning 500 kb around LCT have nearly identical, very high values of pexcess that approximate the frequency of the persistence-associated haplotype (0.77) (fig. 1b). Furthermore, the elevation in pexcess extends for at least 1,500 kb (fig. 1b; table A2 [online only]). To provide a framework for comparison, we calculated pexcess values for marker pairs and the correlation between pairs as a function of distance for >13,000 SNPs throughout the genome; we found that the correlation is normally minimal at distances of as little as 100 kb (r2=0.002). Indeed, in this genomewide data set, none of 952 comparison regions had a consistent elevation in pexcess values approaching that seen around LCT (see the “Subjects and Methods” section for details). These results further mark the LCT region as very unusual when compared with the remainder of the genome, and they strongly suggest that genetic hitchhiking due to selection has occurred: that is, a selected allele rose in frequency over such a short time period that the frequencies of linked alleles on the surrounding >1 Mb haplotype were dragged up as well (Braverman et al. 1995).

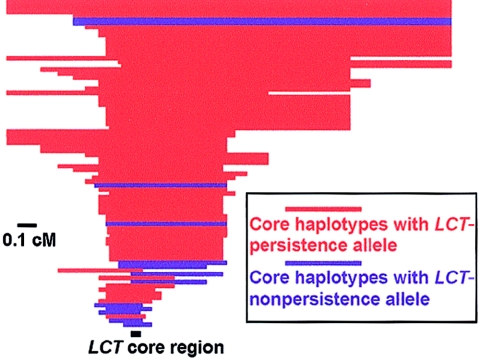

In addition to the tests above, which are measures of differentiation between populations, we also employed the recently described long-range haplotype test of Sabeti et al. (2002), which detects selection by measuring the characteristics of haplotypes within a single population. A recent haplotype should be surrounded by long stretches of homozygosity, since recombination will have had few opportunities to juxtapose adjacent segments from other chromosomes with the selected haplotype. The evidence for selection is a haplotype that arose recently—as evidenced by long flanking stretches of homozygosity—but is so common that the haplotype could not have risen quickly to such high frequency without the aid of selection. We observed precisely this pattern at the haplotype containing the lactase-persistence–associated alleles −13910T and −22018A. The haplotype containing these alleles was very common (77% in European Americans) but also largely identical over nearly 1 cM (>800 kb), indicating a recent origin (red bars in fig. 2). This long stretch of homozygosity was not simply due to a low local recombination rate—the other haplotypes in this region show shorter extents of homozygosity, indicating abundant historical recombination (blue bars near the bottom of fig. 2), and the recombination rate in this region is typical of that in the genome as a whole (Kong et al. 2002).

Figure 2.

Long-range extended homozygosity for the core haplotype containing the persistence-associated alleles at LCT at various distances from LCT. The extent to which the common core haplotypes remains intact is shown for each chromosome in cM. The core region containing −13910C/T is shown as a black bar, and the LCT gene is oriented from left to right. Core haplotypes containing the persistence-associated allele (−13910T) are shown in red, and those containing the non-persistence–associated allele (−13910C) are shown in blue. Haplotypes are from European-derived U.S. pedigrees; all chromosomes with core haplotypes having a frequency ⩾5% in this population are depicted.

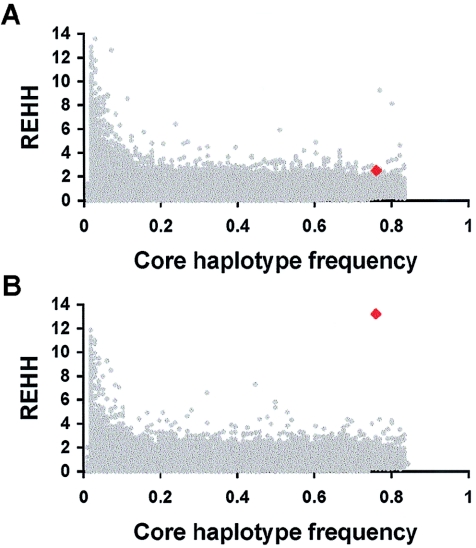

To formally assess the significance of these results, we focused on the REHH statistic (Sabeti et al. 2002); REHH values much greater than 1 indicate increased homozygosity of a haplotype compared with other haplotypes in the region. For the lactase-persistence–associated haplotype, REHH was 13.2 in the region 3′ to LCT, indicating much less breakdown of homozygosity at the persistence-associated haplotype than at haplotypes not carrying the persistence-associated alleles. We compared the LCT data to data from coalescent population-genetics simulations analogous to those in Sabeti et al. (2002), and the empirical P value for excess homozygosity 3′ to LCT was .0004 (fig. 3 and the “Subjects and Methods” section); other estimates of significance suggest a P value closer to 10−7 (see the “Subjects and Methods” section). As confirmation, we compared the LCT haplotype to actual genotype data from 12 control regions spanning 500 kb each. The distribution of REHH was similar for the control regions and the simulations, and the LCT haplotype had a higher REHH than any of the matched control haplotypes. It is notable that the signal for selection is much stronger for LCT than for the well-established case of G6PD—although higher haplotype frequencies are in general associated with lower REHH values (Sabeti et al. 2002) (fig. 3), we observe a larger REHH statistic for the 77% LCT haplotype (REHH=13.2) than for the 18% G6PD haplotype (REHH=7) (see Sabeti et al. 2002). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the extended homozygosity of the high-frequency LCT haplotype is due to dominant suppression of recombination over Mb distances because of an allele on this haplotype, positive selection seems to be a more biologically plausible phenomenon, especially since the haplotype has such a strikingly wide spread of frequencies across European populations. Furthermore, the parental core haplotype on which the persistence-associated alleles arose is present in Asian and African American populations, and it does not have an elevated REHH value (data not shown).

Figure 3.

REHH, a measure of extended haplotype homozygosity, plotted for the persistence-associated haplotype at LCT, in comparison with REHH from haplotypes in 10,000 sets of simulated data (Sabeti et al. 2002). Data are shown using markers (a) 5′ and (b) 3′ to the core region. Data for the LCT-persistence-associated haplotype are indicated by red symbols, and data from simulations are indicated by gray symbols. REHH distributions from actual genotypes for 12 control regions were consistent with the simulated distributions (data not shown).

We next estimated the age of the lactase-persistence–associated haplotype, on the basis of the decay of haplotypes in either direction from the LCT core region (Reich and Goldstein 1998; Stephens et al. 1998). On the basis of our analysis of European-derived U.S. pedigrees, the best estimates of the time at which the persistence-associated haplotype began to rise rapidly in frequency are between 2,188 and 20,650 years ago, consistent with the estimated origin of dairy farming in northern Europe ∼9,000 years ago (Simoons 1970; Kretchmer 1971; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). Even more recent estimates (1,625–3,188 years ago) were obtained by analyzing a Scandinavian population of parent-offspring trios, suggesting stronger and more recent selection in this population. On the basis of these ranges of ages, we estimate the coefficient of selection associated with carrying at least one copy of the lactase-persistence allele to be between 0.014 and 0.15 for the CEPH population and between 0.09 and 0.19 for the Scandinavian population (see the “Subjects and Methods” section for details). By comparison, the selective advantage in a region endemic for malaria has been estimated at 0.02–0.05 for G6PD deficiency (Tishkoff et al. 2001) and 0.05–0.18 for the sickle-cell trait (Li 1975). Thus, the added nutrition from dairy appears to have provided a selective advantage in northern Europe comparable to that provided by resistance to malaria in malaria-endemic regions.

Discussion

We have now demonstrated, on the basis of three different analytic methods (elevated FST at markers associated with lactase persistence, runs of elevated pexcess at flanking markers, and extended haplotype homozygosity), that strong positive selection occurred in a large region that includes the LCT gene. This selection occurred after the separation of European-derived populations from Asian- and African-derived populations, and it likely occurred after the colonization of Europe. The high frequency and young age of this haplotype, the high estimated coefficient of selection, and the very high REHH value all suggest that LCT represents one of the strongest signals of recent positive selection yet documented in the genome. Our results strongly support the hypothesis that the additional nutrition provided by dairy was very important for survival in the recent history of Europe and perhaps in other regions of the world as well.

Our results show that chromosomes carrying the allele associated with lactase persistence (−13910T) share a very long haplotype around this allele. We and others have noted that the presence of this long haplotype raises the possibility that a variant located somewhere in this large region, other than −13910C→T, could be the cause of lactase persistence (Grand et al. 2003; Poulter et al. 2003). Indeed, Swallow and colleagues have identified an individual who is homozygous for the nonpersistence-associated allele at −13910C→T but retains lactase activity (Poulter et al. 2003). Recently, Olds and Sibley (2003) demonstrated differential in vitro transcriptional activity between short segments of DNA carrying the C and T alleles, but the predictive value of such in vitro data for the in vivo phenotype remains uncertain. A comprehensive assessment of variation throughout this long haplotype may be required to determine if −13910C→T is truly the causal polymorphism. Of course, it is also possible that the strong signature of selection is not due to variation at LCT but rather to a coincidental selective event acting on a nearby unrelated gene. However, the striking geographic correlation of lactase persistence with dairy farming (Simoons 1969; Kretchmer 1971; Scrimshaw and Murray 1988) and the recently described evidence of selection on cattle-milk protein genes in regions of Europe with a high prevalence of lactase persistence (Beja-Pereira et al. 2003) lend strong support to the dairy hypothesis.

The −13910T allele was rare or absent in the sub-Saharan African populations we tested, indicating that the presence of the T allele in African Americans that we and Enattah et al. (2002) observed is probably explained by admixture of European-derived chromosomes into the African American population (Parra et al. 1998). Thus, our data do not provide evidence that the −13910T allele predates the differentiation of European and African populations. The absence of the T allele in African populations also suggests that either −13910C/T is not the causal allele or that lactase persistence arose multiple times, because lactase persistence is prevalent in a number of African populations (Scrimshaw and Murray 1988). Consistent with these suggestions, the study by Mulcare and colleagues (in this issue of the Journal) showed that the −13910T allele was absent from several African populations known to have high rates of lactase persistence (Mulcare et al. 2004 [in this issue]). We did not specifically survey these populations, but such surveys will help determine whether lactase persistence arose multiple times in human history or whether a single very old polymorphism rose independently to high frequencies in multiple populations, as has been suggested (Enattah et al. 2002). Finally, the T allele was present at high frequencies in Pakistan and at somewhat lower frequencies in Middle Eastern populations (table 1) and was found on the same local haplotype in these populations as in Europeans (data not shown). These data suggest that individuals carrying the lactase-persistence allele might have migrated between populations (perhaps along with dairy farming), and their descendants may be responsible for the increased allele frequencies in diverse populations in Europe and neighboring regions.

More generally, we have implemented two methods of detecting signatures of positive selection: runs of consecutive markers with elevated pexcess and the long-range haplotype test. It is important to note that these two tests identified LCT as strikingly unusual because LCT was at the far extreme of the genomewide distribution. With the availability of data for loci throughout the genome, empirical comparisons of individual loci to the genomewide distribution will distinguish other genes that are in the extreme tail of the distribution and, thus, are likely to have experienced selection. Ideally, the metrics will be compared not only to an empirical distribution but also to a simulated distribution derived from an appropriate model of recent human evolution that is consistent with empirical data. As models that incorporate more-complete descriptions of human history are developed, such simulations will become more useful.

Both of these methods should be readily applicable to genomewide SNP genotype data being generated by the haplotype map of the human genome (HapMap Project Web site). In particular, runs of markers with consistently elevated pexcess should be detectable once an adequate number of SNPs have been genotyped in multiple populations; our experience with LCT suggests that these runs of elevated pexcess may be more informative than signals from individual markers with high FST values, particularly where selection has dramatically increased the frequency of a single haplotype. The long-range haplotype test should also be useful, even in studies of a single population. Thus, it should be possible in the near future to identify many other loci that have undergone recent positive selection, leading to new insights into recent human evolution and also human disease.

Acknowledgments

D.E.R. and J.N.H. are recipients of Burroughs Wellcome Career Awards in Biomedical Sciences. We thank Richard Grand, Robert Montgomery, Eric Lander, David Altshuler, Helen Lyon, and members of the Hirschhorn Lab for useful comments and discussion.

Table A1.

DNA Samples from Coriell Used in This Study

| Sample ID | Population | Mother ID | Father ID |

| NA06988 | European American | NA07057 | NA06990 |

| NA06983 | European American | NA07057 | NA06990 |

| NA07057 | European American | NA0707 | NA07340 |

| NA07007 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07340 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA06990 | European American | NA07016 | NA07050 |

| NA07016 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07050 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07011 | European American | NA07038 | NA06987 |

| NA07009 | European American | NA07038 | NA06987 |

| NA07038 | European American | NA07049 | NA0702 |

| NA07049 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07002 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA06987 | European American | NA07017 | NA07341 |

| NA07017 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07341 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12138 | European American | NA10846 | NA10847 |

| NA12139 | European American | NA10846 | NA10847 |

| NA10846 | European American | NA12144 | NA12145 |

| NA12144 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12145 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10847 | European American | NA12146 | NA12239 |

| NA12146 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12239 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07053 | European American | NA07029 | NA07019 |

| NA07040 | European American | NA07029 | NA07019 |

| NA07029 | European American | NA06994 | NA0700 |

| NA06994 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07000 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07019 | European American | NA07022 | NA07056 |

| NA07022 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07056 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07006 | European American | NA07048 | NA06991 |

| NA07020 | European American | NA07048 | NA06991 |

| NA07048 | European American | NA07034 | NA07055 |

| NA07034 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA07055 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA06991 | European American | NA06993 | NA06985 |

| NA06993 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA06985 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12040 | European American | NA10857 | NA10852 |

| NA10857 | European American | NA12043 | NA12044 |

| NA12043 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12044 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10852 | European American | NA12045 | NA12046 |

| NA12045 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12046 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11870 | European American | NA10858 | NA10859 |

| NA11871 | European American | NA10858 | NA10859 |

| NA10858 | European American | NA11879 | NA11880 |

| NA11879 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11880 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10859 | European American | NA11881 | NA11882 |

| NA11881 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11882 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11984 | European American | NA10860 | NA10861 |

| NA11985 | European American | NA10860 | NA10861 |

| NA10860 | European American | NA11992 | NA11993 |

| NA11992 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11993 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10861 | European American | NA11994 | NA11995 |

| NA11994 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11995 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12148 | European American | NA10830 | NA10831 |

| NA12149 | European American | NA10830 | NA10831 |

| NA10830 | European American | NA12154 | NA12236 |

| NA12154 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12236 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10831 | European American | NA12155 | NA12156 |

| NA12155 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12156 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12243 | European American | NA10835 | NA10834 |

| NA12244 | European American | NA10835 | NA10834 |

| NA10835 | European American | NA12248 | NA12249 |

| NA12248 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12249 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10834 | European American | NA12250 | NA12251 |

| NA12250 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12251 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12007 | European American | NA10838 | NA10839 |

| NA10838 | European American | NA1203 | NA1204 |

| NA12003 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12004 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10839 | European American | NA1205 | NA1206 |

| NA12005 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA12006 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11909 | European American | NA10842 | NA10843 |

| NA10842 | European American | NA11917 | NA11918 |

| NA11917 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11918 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA10843 | European American | NA11919 | NA11920 |

| NA11919 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA11920 | European American | 0 | 0 |

| NA17031 | African American | … | … |

| NA17032 | African American | … | … |

| NA17033 | African American | … | … |

| NA17034 | African American | … | … |

| NA17035 | African American | … | … |

| NA17036 | African American | … | … |

| NA17037 | African American | … | … |

| NA17038 | African American | … | … |

| NA17039 | African American | … | … |

| NA17040 | African American | … | … |

| NA17101 | African American | … | … |

| NA17102 | African American | … | … |

| NA17103 | African American | … | … |

| NA17106 | African American | … | … |

| NA17107 | African American | … | … |

| NA17108 | African American | … | … |

| NA17109 | African American | … | … |

| NA17111 | African American | … | … |

| NA17112 | African American | … | … |

| NA17114 | African American | … | … |

| NA17115 | African American | … | … |

| NA17117 | African American | … | … |

| NA17119 | African American | … | … |

| NA17122 | African American | … | … |

| NA17124 | African American | … | … |

| NA17125 | African American | … | … |

| NA17132 | African American | … | … |

| NA17134 | African American | … | … |

| NA17136 | African American | … | … |

| NA17137 | African American | … | … |

| NA17139 | African American | … | … |

| NA17140 | African American | … | … |

| NA17144 | African American | … | … |

| NA17147 | African American | … | … |

| NA17148 | African American | … | … |

| NA17149 | African American | … | … |

| NA17152 | African American | … | … |

| NA17155 | African American | … | … |

| NA17156 | African American | … | … |

| NA17157 | African American | … | … |

| NA17158 | African American | … | … |

| NA17159 | African American | … | … |

| NA17160 | African American | … | … |

| NA17169 | African American | … | … |

| NA17172 | African American | … | … |

| NA17196 | African American | … | … |

| NA17197 | African American | … | … |

| NA17198 | African American | … | … |

| NA17199 | African American | … | … |

| NA17200 | African American | … | … |

| NA11321 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA11322 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA11323 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA16654 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA16688 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA16689 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17014 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17015 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17016 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17017 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17018 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17019 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA17020 | Chinese | … | … |

| NA11589 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA11590 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17051 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17052 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17053 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17054 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17055 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17056 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17057 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17058 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17059 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17060 | Japanese | … | … |

| NA17081 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17082 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17083 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17084 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17085 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17086 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17087 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17088 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17089 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

| NA17090 | Southeast Asian | … | … |

Table A2.

FST and pexcess for 101 SNPs around LCT

|

Frequency (%) in |

Value for |

||||||

| SNP ID | Coordinatea | Alleleb | European Americans | African Americans | East Asians | FST | pexcess |

| rs1531957 | 134781635 | T | 21.3 | 8.2 | 26.5 | 0.03 | … |

| rs1996589 | 134887524 | T | 68.8 | 33.0 | 60.0 | .09 | .42 |

| rs1257168 | 134986220 | A | 40.4 | 7.1 | 18.2 | .10 | … |

| rs1257220 | 135037675 | A | 17.7 | 16.0 | 31.4 | .02 | .25 |

| rs842360 | 135370213 | C | 34.4 | 46.8 | 76.5 | .12 | .44 |

| rs1942043 | 135577820 | C | 3.1 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 0 | … |

| rs749017 | 135595987 | G | 30.0 | 44.8 | 30.6 | .01 | .20 |

| rs766271 | 135689459 | C | 55.4 | 30.6 | 46.3 | .03 | .28 |

| rs2322254 | 135773177 | C | 19.8 | 35.0 | 51.4 | .07 | .54 |

| rs1551497 | 135809970 | C | 15.0 | 47.8 | 16.1 | .11 | .53 |

| rs1031575 | 135880258 | G | 3.1 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 0 | … |

| rs2290518 | 135901142 | G | 85.4 | 42.0 | 80.0 | .17 | .63 |

| rs2305594 | 135912936 | C | 9.4 | 6.1 | 15.7 | .01 | … |

| rs4954222 | 135934583 | G | 9.4 | 6.1 | 15.7 | .01 | … |

| rs2305247 | 135950620 | T | 2.1 | 20.0 | 1.4 | .10 | … |

| rs2305248 | 135950640 | A | 85.4 | 40.4 | 81.8 | .19 | .62 |

| rs935612 | 135963831 | A | 88.5 | 42.0 | 92.6 | .27 | … |

| rs4954228 | 135998826 | A | 89.6 | 43.0 | 91.2 | .26 | … |

| rs4954231 | 136038842 | T | 8.1 | 32.0 | 7.6 | .09 | … |

| rs737388 | 136095539 | C | 2.1 | 21.0 | 1.4 | .10 | … |

| rs1469950 | 136150582 | G | 4.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0 | … |

| rs2118395 | 136223648 | T | 7.4 | 4.0 | 7.1 | 0 | … |

| rs4954259 | 136260322 | A | 4.1 | 0 | 3.1 | 0 | … |

| rs1370533 | 136272613 | C | 94.8 | 43.9 | 91.4 | .30 | … |

| rs984763 | 136367366 | A | 2.5 | 4.0 | 7.10 | .00 | … |

| rs2034277 | 136399322 | C | 0 | 15.6 | 0 | .10 | … |

| rs958400 | 136403174 | A | 0 | 35.0 | 0 | .26 | … |

| rs2289963 | 136428206 | A | 6.0 | 10.2 | 8.6 | .00 | … |

| rs4954278 | 136430619 | T | 9.2 | 20.8 | 9.1 | .02 | … |

| rs1438303 | 136452185 | T | 9.4 | 18.4 | 51.4 | .16 | … |

| rs313522 | 136453194 | T | 83.0 | 26.0 | 11.8 | .39 | .79 |

| rs313520 | 136462199 | A | 0 | 11.0 | 0 | .07 | … |

| rs629377 | 136474052 | T | 0 | 13.0 | 0 | .08 | … |

| rs2117511 | 136484989 | A | 90.6 | 43.9 | 64.7 | .16 | … |

| rs2304367 | 136489492 | C | 0 | 13.0 | 0 | .08 | … |

| rs1347767 | 136507985 | G | 0 | 13.0 | 0 | .08 | … |

| rs1438307 | 136521494 | T | 83.0 | 25.0 | 33.3 | .26 | .76 |

| rs3213889 | 136533903 | G | 82.6 | 26.5 | 35.3 | .24 | .75 |

| rs2304601 | 136550362 | A | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | … |

| rs2304602 | 136560269 | G | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | .02 | … |

| rs1030766 | 136575510 | A | 8.3 | 45.0 | 27.1 | .11 | … |

| rs1030764 | 136575857 | T | 86.5 | 47.0 | 62.9 | .11 | .70 |

| rs1011361 | 136575967 | A | 83.3 | 28.0 | 35.7 | .23 | .76 |

| rs2015532 | 136577853 | G | 8.3 | 20.0 | 18.8 | .01 | … |

| rs2322659 | 136577987 | C | 86.4 | 46.0 | 40.0 | .17 | .76 |

| rs872151 | 136579133 | T | 8.3 | 11.0 | 14.3 | 0 | … |

| rs892715 | 136598905 | C | 81.5 | 23.9 | 34.8 | .24 | .74 |

| rs2322812 | 136600368 | G | 5.8 | 12.0 | 14.3 | .01 | … |

| rs2874874 | 136600522 | C | 6.8 | 10.4 | 14.7 | 0 | … |

| rs2164210 | 136602615 | C | 81.3 | 24.5 | 37.1 | .23 | .73 |

| rs1470457 | 136604176 | G | 15.6 | 45.7 | 38.2 | .07 | .63 |

| rs730005 | 136605022 | C | 7.6 | 24.5 | 23.5 | .03 | … |

| rs2322813 | 136605137 | G | 6.8 | 14.6 | 18.3 | .01 | … |

| rs745500 | 136605520 | A | 81.9 | 25.0 | 37.9 | .23 | .74 |

| rs2236783 | 136616486 | A | 81.9 | 25.0 | 32.9 | .25 | .75 |

| rs2082730 | 136629069 | G | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | .06 | … |

| rs4988235 | 136630974 | T | 77.2 | 14.0 | 0 | .53 | … |

| rs2304369 | 136631648 | A | 3.4 | 18.0 | 1.4 | .07 | … |

| rs309180 | 136636583 | A | 82.6 | 23.5 | 32.9 | .26 | .76 |

| rs309181 | 136637141 | G | 81.8 | 26.5 | 42.6 | .21 | .72 |

| rs182549 | 136639082 | T | 77.1 | 13.3 | 0 | .53 | … |

| rs309176 | 136644544 | C | 81.4 | 25.0 | 32.9 | .24 | .74 |

| rs309125 | 136665883 | C | 81.5 | 28.0 | 32.9 | .23 | .73 |

| rs309167 | 136691592 | T | 9.5 | 20.4 | 24.3 | .02 | … |

| rs2322725 | 136699520 | C | 9.1 | 19.0 | 17.1 | .01 | … |

| rs192822 | 136704602 | T | 85.7 | 40.0 | 32.9 | .21 | .78 |

| rs309163 | 136713685 | A | 0 | 8.2 | 0 | .05 | … |

| rs309120 | 136731115 | G | 8.0 | 39.0 | 48.6 | .13 | … |

| rs3112496 | 136733392 | T | 8.3 | 39.8 | 48.6 | .13 | … |

| rs309142 | 136737652 | C | 8.1 | 39.1 | 48.4 | .13 | … |

| rs522086 | 136757469 | T | 0 | 5.1 | 0 | .03 | … |

| rs309118 | 136768552 | C | 8.3 | 26.2 | 46.7 | .12 | … |

| rs309137 | 136788279 | T | 83.3 | 21.0 | 28.6 | .31 | .78 |

| rs1469816 | 136814744 | A | 1.2 | 32.3 | 11.4 | .12 | … |

| rs2090660 | 136841047 | T | 8.8 | 12.2 | 17.6 | 0 | … |

| rs2090663 | 136852863 | G | 0 | 8.2 | 1.4 | .03 | … |

| rs1112156 | 136899042 | A | 0 | 5.1 | 0 | .03 | … |

| rs953388 | 136929457 | T | 12.5 | 5.1 | 32.9 | .09 | … |

| rs2176716 | 136946021 | T | 18.8 | 22.0 | 45.7 | .06 | .45 |

| rs1519523 | 136956777 | T | 52.1 | 22.0 | 25.7 | .07 | .37 |

| rs1519529 | 136996585 | G | 19.5 | 8.0 | 0 | .07 | … |

| rs4440020 | 137012655 | A | 91.7 | 48.0 | 50.0 | .17 | … |

| rs4075810 | 137025473 | T | 3.5 | 4.8 | 46.4 | .26 | … |

| rs4347891 | 137058006 | G | 3.1 | 32.7 | 19.7 | .09 | … |

| rs4245843 | 137062112 | A | 3.1 | 44.0 | 27.3 | .14 | … |

| rs4954411 | 137098753 | T | 58.3 | 25.5 | 18.6 | .13 | .47 |

| rs4501004 | 137129075 | T | 27.1 | 50.0 | 41.4 | .03 | .41 |

| rs2138140 | 137133257 | A | 4.2 | 35.0 | 5.7 | .15 | … |

| rs1399604 | 137152993 | G | 27.9 | 24.0 | 55.7 | .08 | .30 |

| rs867563 | 137164828 | G | 25.0 | 22.4 | 40.0 | .02 | .20 |

| rs578935 | 137233319 | C | 10.4 | 8.0 | 31.4 | .07 | … |

| rs1346822 | 137236689 | A | 9.8 | 15.0 | 24.2 | .02 | … |

| rs694510 | 137303189 | T | 21.8 | 44.4 | 68.3 | .14 | .61 |

| rs876338 | 137311475 | T | 75.0 | 49.0 | 40.0 | .08 | .55 |

| rs1427588 | 137514654 | C | 43.8 | 36.0 | 55.7 | .02 | .05 |

| rs1346731 | 137634915 | A | 40.3 | 19.8 | 20.6 | .04 | .25 |

| rs2370192 | 137649312 | A | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0 | .01 | … |

| rs518614 | 137739179 | C | 61.5 | 18.8 | 14.3 | .20 | .54 |

| rs574135 | 137762448 | G | 62.5 | 27.8 | 19.1 | .14 | .51 |

| rs1432232 | 137821992 | C | 64.6 | 28.0 | 54.3 | .09 | .40 |

| rs882374 | 137935623 | A | 25.0 | 36.0 | 40.0 | .01 | .34 |

Coordinate on chromosome 2, according to the hg15 freeze of the human genome (UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Web site).

Allele shown is the minor allele in the African American population

Electronic-Database Information

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- Coriell Institute for Medical Research, http://locus.umdnj.edu/ccr/

- dbSNP Home Page, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/

- HapMap Project, http://www.hapmap.org

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for HBB, G6PD, FY, TNFSF5, CKR5, HFE, ADH1B, CFTR, and LCT)

- PHASE, http://www.stat.washington.edu/stephens/phase.html

- SNP Consortium (TSC) Web Site, http://snp.cshl.org/allele_frequency_project/

- UCSC Genome Bioinformatics, http://genome.ucsc.edu

References

- Akey J, Zhang G, Zhang K, Jin L, Shriver M (2002) Interrogating a high-density SNP map for signatures of natural selection. Genome Res 12:1805–1814 10.1101/gr.631202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, Lindgren CM, Vohl MC, Nemesh J, Lane CR, Schaffner SF, Bolk S, Brewer C, Tuomi T, Gaudet D, Hudson TJ, Daly M, Groop L, Lander ES (2000) The common PPARγ Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 26:76–80 10.1038/79216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad M, Wooding SP (2003) Signatures of natural selection in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet 4:99–111 10.1038/nrg999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless TM, Rosensweig NS (1966) A racial difference in incidence of lactase deficiency: a survey of milk intolerance and lactase deficiency in healthy adult males. JAMA 197:968–972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beja-Pereira A, Luikart G, England PR, Bradley DG, Jann OC, Bertorelle G, Chamberlain AT, Nunes TP, Metodiev S, Ferrand N, Erhardt G (2003) Gene-culture coevolution between cattle milk protein genes and human lactase genes. Nat Genet 35:311–313 10.1038/ng1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowcock AM, Kidd JR, Mountain JL, Hebert JM, Carotenuto L, Kidd KK, Cavalli-Sforza LL (1991) Drift, admixture, and selection in human evolution: a study with DNA polymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:839–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman JM, Hudson RR, Kaplan NL, Langley CH, Stephan W (1995) The hitchhiking effect on the site frequency spectrum of DNA polymorphisms. Genetics 140:783–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza L (1973) Analytic review: some current problems of population genetics. Am J Hum Genet 25:82–104 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Risch N (1995) A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics 29:311–322 10.1006/geno.1995.9003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enattah NS, Sahi T, Savilahti E, Terwilliger JD, Peltonen L, Jarvela I (2002) Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat Genet 30:233–237 10.1038/ng826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatz G (1987) Genetics of lactose digestion in humans. In: Harris H, Hirschhorn K (eds) Advances in human genetics. Vol 16. Plenum Press, New York, pp 1–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu-Cordero SN, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander ES, Daly MJ, Altshuler D (2002) The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 296:2225–2229 10.1126/science.1069424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grand RJ, Montgomery RK, Chitkara DK, Hirschhorn JN (2003) Changing genes; losing lactase. Gut 52:617–619 10.1136/gut.52.5.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin MT, Thompson EE, Di Rienzo A (2002) Complex signatures of natural selection at the Duffy blood group locus. Am J Hum Genet 70:369–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl D, Clark A (1997) Principles of population genetics. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Hastbacka J, de la Chapelle A, Mahtani MM, Clines G, Reeve-Daly MP, Daly M, Hamilton BA, Kusumi K, Trivedi B, Weaver A, Coloma A, Lovett M, Buckler A, Kaitila I, Lander ES (1994) The diastrophic dysplasia gene encodes a novel sulfate transporter: positional cloning by fine-structure linkage disequilibrium mapping. Cell 78:1073–87 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90281-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollox EJ, Poulter M, Zvarik M, Ferak V, Krause A, Jenkins T, Saha N, Kozlov AI, Swallow DM (2001) Lactase haplotype diversity in the Old World. Am J Hum Genet 68:160–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, Jonsdottir GM, Gudjonsson SA, Richardsson B, Sigurdardottir S, Barnard J, Hallbeck B, Masson G, Shlien A, Palsson ST, Frigge ML, Thorgeirsson TE, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K (2002) A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet 31:241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretchmer N (1971) Memorial lecture: lactose and lactase—a historical perspective. Gastroenterology 61:805–813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC, Krakauer J (1973) Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74:175–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WH (1975) The first arrival time and mean age of a deleterious mutant gene in a finite population. Am J Hum Genet 27:274–286 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcare CA, Weale ME, Jones AL, Connell B, Zeitlyn D, Tarekegn A, Swallow DM, Bradman N, Thomas MG (2004) The T allele of a single-nucleotide polymorphism 13.9 kb upstream of the lactase gene (LCT) (C−13.9kbT) does not predict or cause the lactase-persistence phenotype in Africans. Am J Hum Genet 74:1102–1110 (in this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Chesser R (1983) Estimation of fixation indices and gene diversities. Ann Hum Genet 47:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds LC, Sibley E (2003) Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: functional role as a cis regulatory element. Hum Mol Genet 12:2333–2340 10.1093/hmg/ddg244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osier MV, Pakstis AJ, Soodyall H, Comas D, Goldman D, Odunsi A, Okonofua F, Parnas J, Schulz LO, Bertranpetit J, Bonne-Tamir B, Lu RB, Kidd JR, Kidd KK (2002) A global perspective on genetic variation at the ADH genes reveals unusual patterns of linkage disequilibrium and diversity. Am J Hum Genet 71:84–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnier J, Mears JG, Dunda-Belkhodja O, Schaefer-Rego KE, Beldjord C, Nagel RL, Labie D (1984) Evidence for the multicentric origin of the sickle cell hemoglobin gene in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:1771–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra EJ, Marcini A, Akey J, Martinson J, Batzer MA, Cooper R, Forrester T, Allison DB, Deka R, Ferrell RE, Shriver MD (1998) Estimating African American admixture proportions by use of population-specific alleles. Am J Hum Genet 63:1839–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter M, Hollox E, Harvey CB, Mulcare C, Peuhkuri K, Kajander K, Sarner M, Korpela R, Swallow DM (2003) The causal element for the lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is located in a 1 Mb region of linkage disequilibrium in Europeans. Ann Hum Genet 67:298–311 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DE, Goldstein DB (1998) Estimating the age of mutations using the variation at linked markers. In: Goldstein DB, Schlotter C (eds) Microsatellites: evolution and applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, Cann HM, Kidd KK, Zhivotovsky LA, Feldman MW (2002) Genetic structure of human populations. Science 298:2381–2385 10.1126/science.1078311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B (1982) Fundamentals of biostatistics. Duxbury Press, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Reich DE, Higgins JM, Levine HZ, Richter DJ, Schaffner SF, Gabriel SB, Platko JV, Patterson NJ, McDonald GJ, Ackerman HC, Campbell SJ, Altshuler D, Cooper R, Kwiatkowski D, Ward R, Lander ES (2002) Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature 419:832–837 10.1038/nature01140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrimshaw N, Murray E (1988) The acceptability of milk and milk products in populations with a high prevalence of lactose intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 48:1079–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoons F (1969) Primary adult lactose intolerance and the milking habit: a problem in biologic and cultural interrelations. I. Review of the medical research. Am J Dig Dis 14:819–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— (1970) Primary adult lactose intolerance and the milking habit: a problem in biologic and cultural interrelations. II. A culture historical hypothesis. Am J Dig Dis 15:695–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JC, Reich DE, Goldstein DB, Shin HD, Smith MW, Carrington M, Winkler C, et al (1998) Dating the origin of the CCR5-Δ32 AIDS-resistance allele by the coalescence of haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet 62:1507–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Donnelly P (2003) A comparison of Bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am J Hum Genet 73:1162–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff SA, Varkonyi R, Cahinhinan N, Abbes S, Argyropoulos G, Destro-Bisol G, Drousiotou A, Dangerfield B, Lefranc G, Loiselet J, Piro A, Stoneking M, Tagarelli A, Tagarelli G, Touma EH, Williams SM, Clark AG (2001) Haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium at human G6PD: recent origin of alleles that confer malarial resistance. Science 293:455–462 10.1126/science.1061573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomajian C, Ajioka RS, Jorde LB, Kushner JP, Kreitman M (2003) A method for detecting recent selection in the human genome from allele age estimates. Genetics 165:287–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiuf C (2001) Do ΔF508 heterozygotes have a selective advantage? Genet Res 78:41–47 10.1017/S0016672301005195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]