Abstract

Background:

T Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (Bochdalek hernia), which occurs in 1/2,200 live births, is typically diagnosed in the prenatal or immediate postnatal period. Diaphragmatic hernia is rare in older children and adults and can be presented with acute respiratory failure, incarcerated hernia, acute pancreatitis, or rare conditions such as left portal hypertension and hypersplenism.

Objective:

The aim of this case report was to present 15-year-old male with vomiting and mild upper abdominal pain who had mild epigastric tenderness with no guard and an IV grade splenomegaly caused by Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Case presentation: We report a case of left portal hypertension and hypersplenism in an adolescent with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Typical clinical presentations include abdominal pain, respiratory symptoms, or intestinal obstruction in incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia. Additionally, some uncommon symptoms reported in literature include gastrointestinal bleeding as a result of portal hypertension, thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism, and acute pancreatitis.

Conclusion:

The treatment has released the obstruction in the splenic vein and reduce returned collateral gastric blood flow. Splenectomy should be considered based on many factors, such as anatomic anomalies or the degree of hypersplenism and portal hypertension. This is a rare clinical entity with only a few cases that have been reported in the literature.

Keywords: Bochdalek hernia, Hypersplenism, Portal hypertension

1. BACKGROUND

Traumatic Congenital posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia (Bockdalek hernia), occurring in approximately 1 per 2,200 live births, due to the failure of the closing of the posterolateral diaphragmatic canal, and often presents in the neonatal period with severe respiratory distress (1). Symptoms in older children and adults are extremely rare and often detected incidentally (1). Typical clinical presentations include abdominal pain, respiratory symptoms, or intestinal obstruction in incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia. Additionally, some uncommon symptoms reported in literature include gastrointestinal bleeding as a result of portal hypertension, thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism, and acute pancreatitis (2). Left-sided portal hypertension (LPH) is a rare etiology presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding from ruptured gastric varices (3, 4). Often, the splenic vein is obstructed because of torsion or external compression to the splenic hilum (5). LPH should be considered in all patients presented with a collateral gastric vein and/or splenic vein without esophageal varices and abnormal liver function (4).

2. OBJECTIVE

The aim of this case report was to present 15-year-old male with vomiting and mild upper abdominal pain who had mild epigastric tenderness with no guard and an IV grade splenomegaly caused by Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia.

3. CASE PRESENTATION

A 15-year-old male with no significant past history presented with vomiting and mild upper abdominal pain. On clinical examination, there was mild epigastric tenderness with no guard and an IV grade splenomegaly. Laboratory investigations were normal except for an elevation in amylase and lipase of 188 UI/L and 233 UI/L, respectively. Thrombocytopenia was noted on the complete blood count with platelet count of 58 K/uL. Sonographic findings included swollen pancreatic parenchyma, splenomegaly with a maximum diameter of 189 mm, and normal liver. To screen for portal hypertension, a following Doppler ultrasound was indicated, which showed portal vein diameter of 7.2 mm, and hepatopetal portal venous flow with a velocity of 12 cm/s. There was no thrombosis or collateral circulation.

Figure 1. A. Left diaphragmatic hernia includes intestinal, tail of the pancreas, and left kidney (arrow); B IV grade splenomegaly (arrow).

The patient was hospitalized for a bone marrow biopsy, which was normal. The thrombocytopenia in conjunction with splenomegaly suggested portal hypertension. Therefore, we ordered a CT-Scan with contrast and scheduled an upper GI endoscopy. On imaging, we found a heterogenous enlarged liver without any vascular abnormality and splenomegaly. A large left diaphragmatic hernia was noted, which compressed most of the left lung; the hernia included the entire intestinal, mesentery, the tail of the pancreas, and the left kidney; the mediastinum was shifted to the right and abdominal contents were misplaced.

The operation was indicated to reduce the abdominal contents into the abdomen and repair the left diaphragm. As we also considered the possibility of total or partial splenectomy, a pneumococcal vaccine was given pre-operatively.

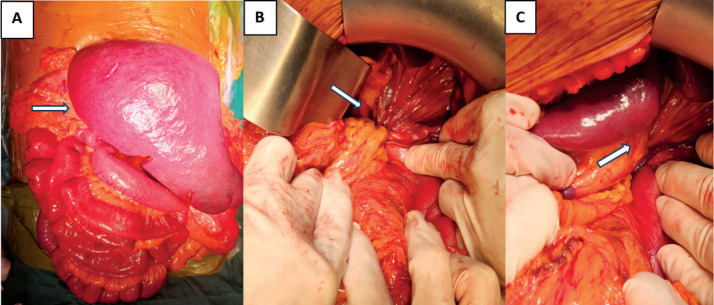

Intraoperatively, we found the colon and small intestine occupying the left thoracic cavity upon entry into the left chest. The spleen was enlarged below the iliac crest but still intra-abdominal. The intestinal mesentery was tightened and twisted, compressing the splenic vein. The superior mesenteric vessels protruded into the chest and also stretched and twisted the splenic vein. We believed those caused hypersplenism and portal hypertension. We decided to conserve the spleen. We also ensured the normal breadth of the mesentery and non-rotating intestines. After the herniation had been repaired, the splenic pedicle was flexible and soft (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Operative photograph showing: A. Grade IV splenomegaly (arrow), B. Splenic veins compressed by herniated mesenteric vessels (arrow), C. Strangulated, twisted splenic vessels (arrow).

The patient was given early oral nutrition (24 hours postoperative) and discharged 9 days later. The platelet count was 81 K/uL on day 3 and 149 K/uL on day 9 postoperatively. A Doppler ultrasound was given at follow-up (21 days postoperative), which showed no increase in portal venous flow velocity and spleen size of 129 mm (a significant decrease compared to pre-operative size of 189 mm). There was no sign of portal hypertension.

4. DISCUSSION

Congenital posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia is first reported in 1848 by Bochdalek (1). This condition, resulting from incomplete closure of the pleuroperitoneal canal, creates a posterolateral defect of the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic hernia is usually discovered in the neonatal period presenting with respiratory distress symptoms and pulmonary hypoplasia (1). Diaphragmatic hernia can also result from penetrating trauma or contusion to the chest or abdominal wall. In the literature, some rare cases of congenital diaphragmatic hernia with late presentation in adolescents or even adults. The estimated prevalence of asymptomatic cases in the population is about 0.17% (2). Symptoms in adults are often vague, comprised of abdominal pain, vomiting, dysphagia, chest pain and dyspnea (1). The herniated viscera may include small intestine, large intestine, stomach, liver or spleen. Chest X-ray may reveal structures containing air or fluid above the diaphragm, thoracoabdominal CT scan with contrast now has become the well-received means of diagnostic (1). In diaphragmatic hernia, wandering spleen is a rare cause but is associated with left-sided portal hypertension (4).

Greenwald and Wasch first described the pathophysiology of left-sided portal hypertension in 1939 (6). As reported, chronic obstruction of splenic vein can induce left-sided portal hypertension, a proven cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding from ruptured gastric varices. Some common causes of splenic vein thrombosis or obstruction are chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts and pancreatic neoplasms (7). Rare etiolgy consist of post liver transplant conditions, ectopic spleen, colonic neoplasms mass effect, splenic vein thrombosis caused by perirenal abscess (8, 9). The obstruction of splenic vein leads to the elevation of blood pressure in the short gastric veins and the gastroepiploic veins, subsequently via the coronary vein into the portal system. This results in the reversal of blood flow in these veins and the formation of gastric varices (10). The diagnosis of left-sided portal hypertension should be considered in all patients who have upper gastrointestinal bleeding with enlarged spleen and normal liver function (4).

LPH and hypersplenism due to CDH are rare, when reviewing the literature, we found a report by R. Kennedy (1) describing a case of CDH in a 21-year-old female with a presentation of hemorrhage due to LPH and hypersplenism. The author explained that the spleen may have herniated through the diaphragmatic defect in infancy and will have outgrown the defect over time (1). Subsequent venous obstruction led to left portal hypertension resulting in hypersplenism. Another report was from a 23-year-old female with recurrent left posteromedial diaphragmatic hernia presented with chest pain, abdominal pain, anemia and gastric varices due to splenic vein compression with the spleen protruding into the chest (2). LPH in patients with wandering spleen is usually presented first with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to gastric variceal bleeding (5). Case reports showed that most patients had symptoms of portal hypertension, gastrointestinal bleeding and were indicated by an abdominal CT-scan to screen for causes (3, 4, 7, 11). In our reported case, the 16-year-old male presented with hypersplenism and a IV grade splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia. Therefore, he was given a CT-scan to examine the portal system for the cause. He was diagnosed early as asymptomatic. However, compared to the above two cases, we found the spleen did not occupy the left thoracic cavity (on Ultrasound, CT-Scan and during operation). We also found the superior mesenteric vessels protruded into the chest which tightened and twisted the splenic vein. We believed those caused hypersplenism and portal hypertension.

In treatment of CDH, controversy exists regarding the surgical approach to repair (12). Thoracotomy advocates cite an improved ability to divide chronically formed adhesions between abdominal viscera and thoracic structures (13). Laparotomy however, allows resection of diseased or abnormal organs such as necrotic bowel or enlarged spleen (14). The diaphragm defect may be closed primarily using sutures or by covering the defect with an appropriately sized non-absorbable mesh. Abdominal compartment syndrome can occur following closure of the diaphragm, and staged closure of the abdomen may be required. In our case, we decided to operate through the abdominal route as we wanted to review the portal system, especially splenic vessels, and due to the potential splenectomy, we had considered preoperatively.

Discussion on whether splenectomy should be done, in the two above reports, author Kennedy R. (1) conducted diaphragm repair and splenectomy, on the other hand, author Daniel F. (2) only reduced the herniated viscera and closed the diaphragmatic defect. In reports of LPH and hypersplenism in wandering spleen or chronic splenic torsion, elective splenectomy is recommended in cases of serious hemorrhage due to LPH (13). Splenic artery ligation decompressed the gastric varices (14). However, spleen conservation or partial splenectomy is also accepted in asymptomatic patients or those only presented with mild hemorrhage. In our case, the herniated intestines, colon, and tail of the pancreas led to compressed and twisted mesentery, resulting in splenic vein dilation, splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia. Therefore, we believe that reducing the herniated viscera and releasing tension on the tail of pancreas and splenic vein could relieve portal hypertension and hypersplenism. Besides, our patient only had thrombocytopenia without pancytopenia or gastrointestinal hemorrhage, for which we decided to conserve the spleen and set up follow-up evaluation for spleen function, and portal pressure response postoperatively. Splenectomy could be considered if portal hypertension remained or hypersplenism developed into pancytopenia or gastrointestinal hemorrhage (14). Postoperatively, our patient recovered relatively well and had marked improvement in spleen function.

5. CONCLUSION

Left portal hypertension and hypersplenism in a patient with congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a rare condition. The hernia could cause splenic torsion due to the loosening of the spleen fixations, splenomegaly, and the herniated intestinal could cause strangulation of the splenic vein, eventually leading to left portal hypertension and hypersplenism. The goal of treatment is to release the obstruction in the splenic vein and reduce returned collateral gastric blood flow. Splenectomy should be considered based on many factors, such as anatomic anomalies (wandering spleen, splenic torsion) or the degree of hypersplenism and portal hypertension.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge patients who participated in this study.

Availability of data and materials:

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Author’s contribution:

Tran TT and Trinh-Nguyen HV: Case file retrieval and case summary preparation. Tran TT and Trinh-Nguyen HV: preparation of manuscript and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support and sponsorship:

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kennedy AD, Ahmad J, McManus K, Clements WDB. Portal hypertension and hypersplenism in a patient with a Bochdalek hernia: a case report. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:111–113. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farinas D, Nedimyer JD, Vanetta C, Boyer J. Bochdalek hernia recurrence presenting as bleeding from gastric varices in adulthood. Am Surg. 2023;89(12):6233–6234. doi: 10.1177/00031348221121548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.PedroPereira A. Left-sided portal hypertension: a clinical challenge. Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22(6):231–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jpge.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kokabi N, Echevarria C, Loh C, Kee S. Sinistral portal hypertension: presentation, radiological findings, and treatment options - a case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4(10):14–20. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i10.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha AK, Dayal VM, Suchismita A. Torsion of spleen and portal hypertension: pathophysiology and clinical implications. World J Hepatol. 2021;13(7):774–780. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i7.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwald HM, Wasch MG. The roentgenologic demonstration of esophageal varices as a diagnostic aid in chronic thrombosis of the splenic vein. J Pediatr. 1939;14(1):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG, Smyrniotis VE, et al. The significance of sinistral portal hypertension complicating chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2000;179(2):129–133. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angerås U, Bengmark S, Malmström P. Acute gastric hemorrhage secondary to wandering spleen. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:1159–1163. doi: 10.1007/BF01317093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melikoğlu M, Colak T, Kavasoğlu T. Two unusual cases of wandering spleen requiring splenectomy. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5(1):48–49. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1066163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glynn MJ. Isolated splenic vein thrombosis. Arch Surg. 1986;121(6):723–725. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400060119018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans G, Yellin AE, Weaver FA, Stain SC. Sinistral (left-sided) portal hypertension. Am Surg. 1990;56(12):758–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalencourt G, Katlic M. Abdominal compartment syndrome after late repair of Bochdalek hernia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:721–722. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson WS, Bolton JS. Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12(4):277–280. doi: 10.1089/109264202760268078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fingerhut A, Baillet P, Oberlin PH. More on congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the adult [letter] Int Surg. 1984;69:182–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.