Abstract

Joubert syndrome (JS) is an autosomal recessive disorder marked by agenesis of the cerebellar vermis, ataxia, hypotonia, oculomotor apraxia, neonatal breathing abnormalities, and mental retardation. Despite the fact that this condition was described >30 years ago, the molecular basis has remained poorly understood. Here, we identify two frameshift mutations and one missense mutation in the AHI1 gene in three consanguineous families with JS, some with cortical polymicrogyria. AHI1, encoding the Jouberin protein, is an alternatively spliced signaling molecule that contains seven Trp-Asp (WD) repeats, an SH3 domain, and numerous SH3-binding sites. The gene is expressed strongly in embryonic hindbrain and forebrain, and our data suggest that AHI1 is required for both cerebellar and cortical development in humans. The recently described mutations in NPHP1, encoding a protein containing an SH3 domain, in a subset of patients with JS plus nephronophthisis, suggest a shared pathway.

Introduction

The mammalian cerebellum consists of two hemispheres and a midline structure known as the “vermis,” which is responsible for coordination of midline movements. The most common disorder affecting the development of this structure is Joubert syndrome (JS [MIM 213300]), but the molecular determinants of this condition are poorly understood. A key radiographic hallmark of JS is the “molar tooth malformation” (MTM) seen on axial brain imaging, which is a result of a malformed cerebellar vermis, thick and elongated cerebellar peduncles, and a deep interpeduncular fossa (Maria et al. 1997). There is significant clinical heterogeneity in conditions displaying cerebellar vermis hypoplasia and the MTM. Some patients display the classic form of JS that includes the MTM, ataxia, hypotonia, oculomotor apraxia, neonatal breathing abnormalities, and mental retardation without extra-CNS involvement. Others also exhibit ocular colobomas, polydactyly, liver fibrosis, cystic dysplastic kidneys, retinal blindness, and/or nephronophthisis (NPHP [MIM 256100]). Distinct syndromes seen with JS and the MTM have been identified and differ by their extra-CNS phenotype (Saraiva and Baraitser 1992; Chance et al. 1999; Satran et al. 1999; Valente et al. 2003). Altogether, there appears to be no less than eight of these distinct syndromes, and they are collectively referred to as “Joubert syndrome and related disorders” (JSRD) or “cerebello-oculo-renal syndromes” (CORS [MIM 608091]). It is interesting that one of these syndromes is marked by JS with the addition of cortical polymicrogyria (Gleeson et al. 2004), a brain abnormality characterized by excessive cortical folding, shallow sulci with walls that are fused in the deepest portions, and a simplified four-layered or unlayered cortical architecture (Barkovich et al. 1999; Ribacoba Montero et al. 2002).

There is genetic heterogeneity that mirrors this clinical heterogeneity seen in JS. Three causative loci have been mapped, including JBTS1/CORS1 at 9q34.3 (Saar et al. 1999), JBTS2/CORS2 at 11 centromere (Keeler et al. 2003; Valente et al. 2003), and JBTS3/CORS3 at 6q23 (Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2004). The phenotypes of the families mapping to JBTS1 and JBTS3 were similar, displaying minimal extra-CNS involvement. One of six patients mapping to the JBTS1 locus displayed retinal dystrophy, and none showed NPHP or renal cysts, although these were not specifically tested in all patients. Likewise, only two of the seven JBTS3-mapped patients displayed extra-CNS involvement—specifically, retinal dysplasia. On the other hand, families mapping to JBTS2 displayed strong evidence of kidney involvement and additional eye involvement. Of 11 patients, 6 displayed renal cysts or NPHP, 2 displayed retinal dysplasia, and 4 displayed optic coloboma. Together, the data suggest that the JBTS1 and JBTS3 phenotypes usually do not involve retinal or renal abnormalities, whereas these are frequently seen in the JBTS2 phenotype.

Highlighting these genetic and phenotypic differences is the recent finding of a mutation in NPHP1—a gene mutated in some patients with NPHP or Senior Löken syndrome (NPHP with retinal dystrophy)—in two siblings with Senior Löken syndrome plus a mild form of JS (Parisi et al. 2004). The NPHP1 gene encodes for the nephrocystin protein, which contains an SH3 domain, and has been implicated in intracellular signaling and possibly ciliary function (Hildebrandt et al. 1997; Otto et al. 2003).

Here, we show evidence that mutations in AHI1, which encodes the Jouberin protein at the JBTS3 locus, cause JS with polymicrogyria. Findings similar to these were published in a recent article (Ferland et al. 2004), in which mutations in AHI1 were seen with pure JS with no retinopathy or supratentorial involvement. The present work provides independent verification of the involvement of AHI1 in Joubert syndrome and suggests a broader AHI1 phenotype that includes a role in cortical development as well as cerebellar development.

Methods

Genotyping

Homozygosity mapping was performed on 18 consanguineous families that were previously excluded from linkage to the JBTS1 and JBTS2 loci. Subjects were mapped at six different markers spanning the JBTS3 locus, which was previously defined by the markers D6S1620 and D6S1699 (Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2004). This study was performed in accordance with a University of California Human Subjects Committee–approved protocol.

After informed consent was obtained from all family members, blood samples were drawn, and DNA was extracted, using standard procedures. Microsatellite markers were amplified by standard PCR with primers that corresponded to sequence from the Human Genome Browser. Heat-denatured PCR products were loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing urea and were run by electrophoresis for 2.5 h at 40°C. Bands were visualized using a standard silver-staining protocol (Promega).

Mutation Screening

Primers were designed for all coding exons and for at least 50 bp of the intronic sequence that contained the 5′ and 3′ splice junctions, by use of the Primer3 program (table A1 [online only]). PCR products were purified using an exonuclease I and shrimp-alkaline-phosphatase protocol and were sequenced using an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer. Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher 4.1 software. Genomic sequence for human AHI1 was obtained from the Human Genome Browser (accession numbers AJ606362, AJ459825, and AK024085) and was used for primer design.

Northern-Blot Analysis

Mouse probe DNA fragments for exons 6–10 were designed as stated above, by use of sequence from the mouse genome query of the Human Genome Browser (accession numbers NM_026203, BB615071, and BG297436). Probes were then labeled with [α-32P]dCTP, by use of the Stratagene Prime-It RmT Labeling Kit. A Clontech Multiple Tissue Mouse Northern (MTN) blot was used to test for expression. Mouse tissues from postnatal day 0 (P0) were used to isolate total mRNA by Trizol and were similarly analyzed by northern analysis. Northern blots were hybridized with the labeled probe, by use of the Clontech MTN ExpressHyb protocol.

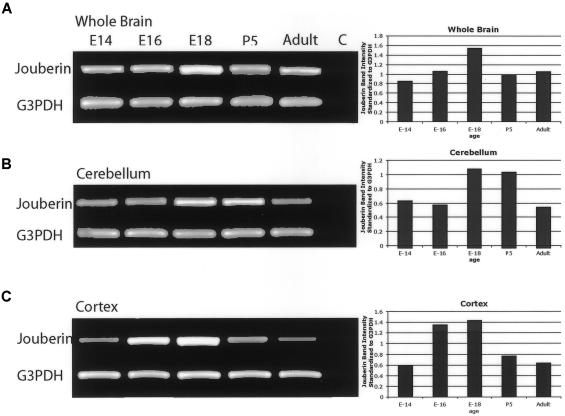

RT-PCR

Total RNA from whole brain, cerebellum, and cortex of mice was isolated using a standard Trizol procedure, at five different time points. First-strand cDNA was generated using Superscript II (Invitrogen) with RNase H− reverse transcriptase and oligo dT. cDNA was amplified with primers for Jouberin exons 6–9 and for G3PDH, by a 50-μL reaction with a final primer concentration of 300 nM. Band intensities were quantified using ImageQuant v.1.1 (Molecular Dynamics), and each band intensity for Jouberin was standardized relative to its G3PDH control.

Animal Subjects

All work was done in accordance with the University of California–San Diego Animal Subjects Program.

Results

Mutations in AHI1 Are Seen in JS

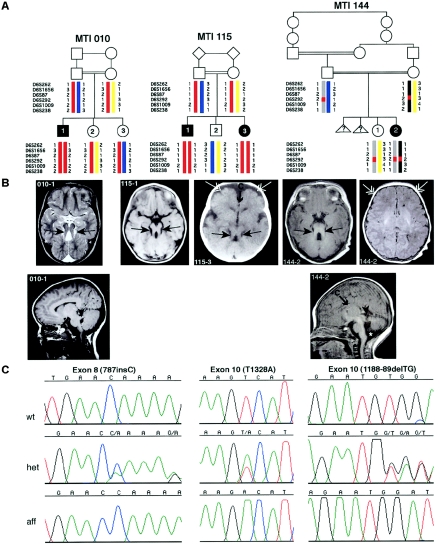

Two families (10 and 115) showed linkage across the entire JBTS3 interval, and one family (144) refined the candidate interval by showing homozygosity at a single marker (D6S292), which suggests a double recombination (fig. 1). Four genes within JBTS3 were chosen for candidate analysis: AHI1, MAP7, OLIG3, and KIAA1244. Of these, only AHI1 and MAP7 were adjacent to D6S292. AHI1 mutational analysis of all coding exons in genomic DNA showed two frameshift mutations in exon 8 (fsX270) and exon 10 (fsX408) and one missense mutation in exon 10 (V443D). On the basis of these results, we named the predicted protein “Jouberin.”

Figure 1.

Mutations in AHI1, which encodes Jouberin, lead to cerebellar vermis aplasia, the MTM, and cortical polymicrogyria. A, Genotypes of the three consanguineous families displaying evidence of linkage to the JBTS3 locus. Affected members of family MTI (molar-tooth on brain imaging) 010 and MTI 115 display homozygosity for markers across the entire region (double red bar), whereas the affected individual in family MTI 144 shows homozygosity for only a single marker (D6S292), which suggests a double recombination. Triangles with question marks (?) represent unknown sex and affection status. B, Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of each of the JBTS3-linked families corresponding to the pedigrees above. Top row, Axial images showing the MTI (blackened arrows), frontal polymicrogyria (unblackened arrows), and thin corpus callosum (arrow with C). Bottom row, Midline sagittal images showing horizontal superior cerebellar peduncle (arrowheads). The asterisk (*) represents mega cisterna magna. Additional scans showing polymicrogyria in patient 144-2 can be found in figure A1 (online only). C, Sequence chromatograms corresponding to the families above. Family MTI 010 displays a single-base insertion at position 787 in exon 8, family MTI 115 displays a T1328A point mutation in exon 10, and family MTI 144 displays a 2-base deletion at positions 1188–89, each of which leads to deleterious mutations in the Jouberin protein.

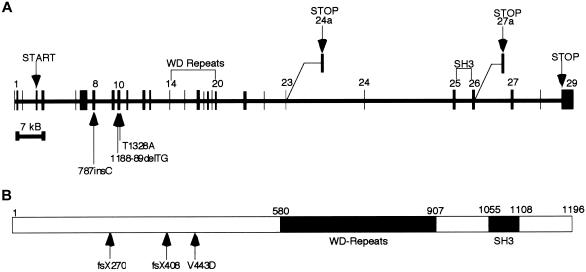

Jouberin, Encoded by the AHI1 Gene, Is a Predicted Signaling Molecule

The human Jouberin protein has three known isoforms and contains seven WD40 domains and one SH3 domain (fig. 2). Both human AHI1 and mouse Ahi1 have been described elsewhere (Jiang et al. 2002), and human AHI1 has been further characterized as having an N-terminal coiled-coil domain (Ferland et al. 2004). Numerous additional domains have been predicted in this protein by use of ScanProsite analysis; among them are multiple SH3-binding sites.

Figure 2.

Exonic structure of AHI1 and the Jouberin protein, including patient mutations. A, The gene encoded in ∼215 kb of genomic DNA and that contains 31 exons, 2 of which are alternatively spliced, producing shorter isoforms. Patient mutations are indicated by arrows and occur in exon 8 and exon 10. B, The predicted full-length human Jouberin protein gives a 1,196-aa message with seven WD40 repeats and an SH3 domain.

Database analysis and literature review showed that the human AHI1 gene contains 31 exons; two that are alternatively spliced (exon 24a and exon 27a), giving rise to the different isoforms. Alternative splicing occurs in both the 5′ UTR and the 3′ end of the Jouberin protein after the WD repeats. The consequences of the 5′ UTR alternative splicing are not readily apparent; however, the 3′ splicing yields two isoforms of the protein that lack either the SH3 domain or the far C-terminus of the protein. Exon 24a is used for a message that is ∼3.5 kb in size. Exon 27a is used for a truncated isoform that produces a message mirroring the full-length ∼4.7-kb message. An earlier publication (Jiang et al. 2002) reported two other alternatively spliced exons, both of which encode alternate ORFs. However, no evidence for these splice variants could be found in the public database by querying the spliced ESTs or mRNAs. The function of the gene is currently unknown, but the presence of the SH3 domain suggests a role as a signaling molecule.

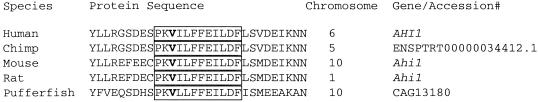

In the affected child of family 10, the frameshift mutation in exon 8 is caused by the presence of an extra cytosine (787insC) in the ORF and truncates the Jouberin protein at amino acid 270, which eliminates the WD repeats and SH3 domain (figs. 1 and 2). The parents and unaffected siblings carry this mutation. In the affected child of family 144, the frameshift mutation in exon 10 is caused by a 2-base deletion (188-89delTG) in the ORF, truncating the protein at amino acid 408 and also eliminating the WD repeats and SH3 domain. Both parents and the unaffected sibling in this family carry this mutation. In both affected individuals of family 115, the missense mutation in exon 10 changes a valine to aspartic acid (V443D), a mutation that is not seen in the unaffected family members. The valine is an evolutionarily conserved amino acid, seen in all species that contain a Jouberin orthologue for which sequence was available (fig. 3). The mutation also segregates with the phenotype in this family. None of these mutations were observed in 50 Middle Eastern controls.

Figure 3.

Conservation of amino acids surrounding the mutation (V443D) in family 115. The mutated valine (V) is highlighted, and the boxed area shows the sequence conservation among diverse species.

Patients with Jouberin Mutations Display JS Plus Polymicrogyria

The clinical features of the patients with Jouberin mutations were examined in detail (table 1). They displayed the clinical hallmarks of JS, and all had the MTM (fig. 1). None of these patients showed evidence of renal involvement, but two, from the same family, displayed evidence of retinal dysplasia. These data are consistent with previous findings that this locus is not associated with striking retinal or renal involvement, and they suggest a role for this gene in cerebellar development.

Table 1.

Phenotypic Characteristics of Patients with AHI1 Mutations

|

Finding in Affected Individuala |

||||

| Characteristic | 10-1 | 115-1 | 115-3 | 144-2 |

| National origin | Palestinian | Kuwaiti | Kuwaiti | Turkish |

| Exon with mutation | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Nucleotide changes | 787insC | T1328A | T1328A | 1188–89delTG |

| Alterations in coding sequence | fsX270b | V443D | V443D | fsX408b |

| MTM | + | + | + | + |

| Cerebellar vermis aplasia/hypoplasia | + | + | + | + |

| Breathing abnormalities | + | NA | NA | + |

| Ataxia/hypotonia | + | + | + | + |

| Mental retardation | + | + | + | + |

| Oculomotor apraxia | + | + | + | + |

| Retinal involvement | NA | Rod-cone dysfunction | Rod-cone dysfunction | NA |

| Supratentorial abnormalities | Enlarged lateral ventricle | Thin corpus collosum, frontal polymicrogyria | Thin corpus collosum, frontal polymicrogyria | Thin corpus collosum, possible frontal polymicrogyria |

| Coloboma | − | − | − | − |

| Kidney involvement | − | − | − | NA |

| Other | − | − | − | Atrial septal heart defect |

NA = not available; + = positive for the characteristic; − = negative for the characteristic.

fs = frameshift.

These patients appear to have a supratentorial phenotype, with two patients in one family showing clear evidence of polymicrogyria, a disorder of cerebral cortex development in which there are supernumary small gyri. There was also evidence in these families of corpus collosum abnormalities. Both affected members of family 115 display a thin corpus collosum and frontal polymicrogyria, the single affected member of family 144 displays a thin corpus collosum and likely frontal polymicrogyria, and the single affected member of family 10 displays enlarged lateral ventricles. These data suggest a further role for the gene in development of the cortex.

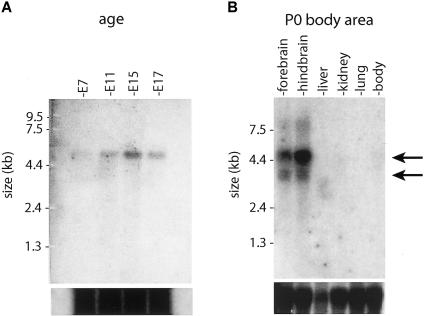

Jouberin Is Expressed in Mouse Brain during Development

To characterize the function of Jouberin, a northern blot containing total mRNA was probed at a series of embryonic time points with mouse exons 6–10 of Ahi1, a region that is not known to be alternatively spliced. Expression was first evident at embryonic day 7 (E7) and was also present at E11, E15, and E17, with the most intense band occurring at E15 (fig. 4). Each time point showed a single band at ∼4.7 kb, which represents the full-length variant of mouse Ahi1. Northern-blot analysis was also performed to determine regional distribution of expression for P0 mouse. The strongest levels of expression were seen in the hindbrain and forebrain, which showed two bands at ∼4.7 and 3.5 kb, corresponding to the full-length isoform and the isoform lacking the SH3 domain, respectively (Jiang et al. 2002). These data suggest that Jouberin is expressed strongly during periods of both cortical and cerebellar development, consistent with the phenotypes seen in these patients.

Figure 4.

Northern-blot analysis of Ahi1 (Jouberin) expression patterns in mice. A, Total mouse embryonic (E) 7–17 polyA mRNA was probed with a fragment of Ahi1 corresponding to exons 6–10. Expression was first evident at E7 and remained strong at E11, E15, and E17. There is a single band at ∼4.7 kb (arrow) corresponding to the mouse Ahi1 gene from the Human Genome Browser. B, Total mRNA from mouse organs, aged P0, probed with the same Ahi1 fragment. Strongest expression was shown in the hindbrain and forebrain, with two bands visualized at 4.7 kb and 3.5 kb (arrows), corresponding to the two major splice variants (fig. 3). Total mRNA loading control is shown below.

On the basis of the cortical and cerebellar phenotypes in these families, expression was characterized in these two regions separately, by RT-PCR analysis across the developmental spectrum. Whole brain, cerebellum, and cortex were isolated from mouse E14 through adulthood at several stages and were tested for expression by use of primers that amplified exons 6–9 to identify signal from only spliced message. Expression of Jouberin was detected in whole brain at all time points analyzed (fig. 5). Expression in cerebellum appeared maximal at E18 and P5, whereas expression in cerebral cortex appeared maximal at E16 and E18. This expression corresponds to the periods of maximal development of these two brain regions, with cortical development preceding cerebellar development by several days in mice (Goffinet and Rakic 2000). Expression continued through adulthood, but at lower levels. These data suggest that Jouberin may exert its major effect during late embryonic development.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR of Ahi1 (Jouberin) expression in mouse whole brain, cerebellum, and cortex, at different time points. Band-intensity quantification (standardized against G3PDH controls) revealed that Jouberin showed increasing and then decreasing expression as development progressed. Maximum expression occurred in the cerebellum at E18 and P0, and maximum expression occurred in the cortex at E16 and E18. Decreased but persistent expression in the adult was also evident. G3PDH controls are shown below. C = negative control.

Discussion

We present evidence that homozygous mutations in the AHI1 gene lead to JS with polymicrogyria. Mutations in AHI1 were found in patients with classic features of JS, including the MTM and cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, which are the current diagnostic criteria for JS. The majority of these patients did not display evidence of retinal involvement, and none displayed renal involvement, which suggests minimal overlap with the JBTS2/CORS2 phenotype. In addition, polymicrogyria was seen in two—and possibly three—of four patients, whereas enlarged cerebral lateral ventricles and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum were seen in the remaining patients. This suggests that a cerebral cortical phenotype exists among patients with JS and with AHI1 mutations.

We recently identified a subtype of JS with polymicrogyria that was found in 2 of ∼100 patients with posterior fossa malformations. These patients did not display mental retardation beyond the range expected in JS, spasticity, microcephaly, or seizures, which would be typical findings in patients with polymicrogyria (Gleeson et al. 2004). In addition, none of the patients presented here, who do not overlap with those published elsewhere, reported these findings. However, there is other evidence of a cerebral cortical phenotype among patients with linkage to the JBTS3 locus, since one patient studied by Lagier-Tourenne et al. (2004) displayed spasticity, microcephaly, and seizures. The data together suggest that mutations in AHI1 can produce typical JS, JS plus retinal involvement, or JS plus polymicrogyria but that renal involvement is uncommon among these patients.

The AHI1 gene (“Abelson helper integration-1”) was named because of frequent integration of helper provirus at this locus in Abelson murine leukemia virus–induced lymphoma (Jiang et al. 2002). Involvement in leukemogenesis has been suggested by the high frequency of AHI1 mutations seen in certain virus-induced murine leukemias. Expression is high in most primitive hematopoietic cells, with specific patterns of downregulation in different lineages (Jiang et al. 2004), which suggests that downregulation is an important conserved step in primitive normal hematopoietic cell differentiation. Although the expression data that suggest a role for AHI1 in hematopoiesis is compelling, none of the patients presented here showed evidence of hematopoietic abnormalities on routine laboratory evaluations. Whether the gene plays a critical or redundant role in hematopoiesis remains to be determined.

We found that Ahi1 expression begins around E7 and continues through adulthood. Northern-blot analysis indicated the presence of two bands—a 4.7-kb and a 3.5-kb isoform—that correspond to the known transcripts from other organs, including brain (Jiang et al. 2002), although only the longer isoform was identified by Ferland et al. (2004) by northern-blot analysis.

Jouberin homologues were identified in all mammalian species examined, with high conservation in the WD40 and SH3 domains but lower conservation in the N- and C-termini. Highly conserved is the stretch of amino acids surrounding the V443D that was found to be mutated in family 115. An identical V443D mutation was also found by Ferland et al. (2004), who also identified two other premature stop codons among three families with autosomal recessive JS without a cerebral cortical phenotype (Ferland et al. 2004). Family 115 resides in Kuwait, whereas the family with the V443D mutation studied by Ferland et al. (2004) resides in Saudi Arabia, which, because of the relative proximity of these countries, suggests a possible founder effect. Analysis by ScanProsite indicates that this residue may be part of a phosphorylation site by protein kinase C (PKC) at the serine that is 4 aa in the N-terminal direction (Jiang et al. 2002). Typically, there are hydrophobic amino acids such as valine after the serine in PKC sites, and a mutation of this residue to an aspartic acid might block this predicted phosphoprotein event. Although this finding is speculative, it raises the possibility that Jouberin may be a phosphoprotein under the control of PKC-related kinases.

The most highly conserved regions of Jouberin are the SH3 domain and the WD40 repeats. These domains are found in many signaling molecules, where they function as adaptor domains for protein-protein interactions. SH3 domains typically bind to PXXP motifs (known as “SH3-binding domains”) to modulate these interactions. Recently, we showed that mutations in NPHP1 are found in a subset of patients with JS combined with NPHP (Parisi et al. 2004), and it is interesting that both of the encoded proteins of NPHP1 and the Jouberin protein contain highly conserved SH3 domains. Additionally, Jouberin contains multiple PXXP domains, which suggests that it may function with—or directly bind to—the NPHP1 protein.

The NPHP gene family now consists of four genes of diverse function, but it is becoming increasingly clear that the NPHP proteins play critical roles in the function of the cilia. The encoded proteins for NPHP1 and NPHP2 colocalize to the primary cilia in renal epithelial cells (Otto et al. 2003). Furthermore, loss-of-function experiments in zebrafish and mice suggest that these proteins have roles in the establishment of left-right axis determination in motile cilia (Mochizuki et al. 1998) and in the pathogenesis of cystic kidney disease in nonmotile cilia (Otto et al. 2003). The NPHP data suggest a possible role in cilia development, maintenance, or transport, although the direct mechanism has yet to be identified. The function of Jouberin remains to be determined, but it will be interesting to test for its interaction with the NPHP genes and its involvement in cilia function.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families, for their participation, and Ms. Anne John, for technical assistance. We thank the Joubert Syndrome Foundation for their support of this research. This work was funded by grants from the March of Dimes and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Appendix A:

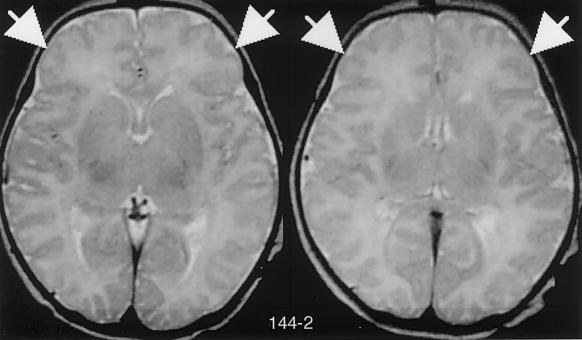

Figure A1.

Additional brain images of patient 144-2, showing polymicrogyria (arrows). The MTM is not visible in these planes.

Table A1.

Primer Sequence for Analysis of Coding Exons of AHI1 (Jouberin)

| Exon and Primer Name | Primer Sequence |

| Exon 4: | |

| 4F | TGGCATGATCTTGTGTGAAGA |

| 4R | TTGTCCATCTGAGTCCCAAAC |

| Exon 5: | |

| 5F | AGTGTAGGTTGTGTGTTATGATAGAGTCA |

| 5R | TGCAGCCATATCTGCATTTTAT |

| Exon 6: | |

| 6F | TGTCTTCCTTTTTAGCCTGACA |

| 6R | TGGACAAAAACCATTGCTGA |

| Exon 7: | |

| 7AF | CTGAAACTTTGTTATCATGTCTTCT |

| 7AR | TCCCTCATTTGCCTTCTCACTTTT |

| 7BF | CAGAAAACACATACAAAGCCACAGC |

| 7BR | AAGAATTTTCTTTGTTAAACCACA |

| Exon 8: | |

| 8F | TTGCTCCTATTTACTGTTCACTCTG |

| 8R | CAAACTCATCAGAGACCTACAGCT |

| Exon 9: | |

| 9F | TCTTTCCCCCTGAAGTTCCT |

| 9R | TCCCACTGACTTTCAACTACCA |

| Exon 10: | |

| 10F | TTTCTCACCTCAAAATTATGAAAA |

| 10R | TCGTTTAATTTGAATTGGTCCAT |

| Exon 11: | |

| 11F | GGTAGCTTAGTCTTCTGTGAATTT |

| 11R | GATTTGGGAGAAAGCAGCCAAC |

| Exon 12: | |

| 12F | CAGCATGCCATATTAATCTTTTA |

| 12R | TGAAAAACATGCTATGTCACCA |

| Exon 13: | |

| 13F | TTTTTATGGCTTTTTGGTTACAGG |

| 13R | TGGAAAGGCAAAATTGTGGTTAAA |

| Exon 14: | |

| 14F | TAGCCTTCGCGTTTTAATGTTT |

| 14R | CAGGGGATTACTCAAGTTAAGATTTCCA |

| Exon 15: | |

| 15F | TTGGATTAAGGATCTTCTGTCTGGA |

| 15R | CTTGACAGCAAACAGCATGCAC |

| Exon 16: | |

| 16F | TTCAGAAGCAATATGTAACTTCTTATCC |

| 16R | GCTGGTCTTCATTCATAGTCTCTGACATAC |

| Exon 17: | |

| 17F | TGGGGTATAGTTTCCCCCGATT |

| 17R | TCATGTGATTGGATTTTTCCAACTTC |

| Exon 18: | |

| 18F | GCATCCTATACAGTGGAATTGGAAATG |

| 18R | TGTGAGTACTTATCCTGTCAACACTGAAA |

| Exon 19: | |

| 19F | GAGAAAAGATTTTATACCACCAGTCA |

| 19R | ACCCCTGTACCTCCCCAAATGA |

| Exon 20: | |

| 20F | AAATGGCAGAATAATCTTGTGAGA |

| 20R | TTCCAGACAGATTCCTGGTTTAG |

| Exon 21: | |

| 21F | AGGGCTTGATTATGCTTTTGCT |

| 21R | GGATAGAAATAGTTTTAAAGTTTCAACTGC |

| Exon 22: | |

| 22F | TCCAAATGCTGATTTAGGTTATT |

| 22R | TGGTGCATTCCAGTTCTTTGGA |

| Exon 23: | |

| 23F | TTGACCTATCATGTGTCCTGGTTTG |

| 23R | TCAACACAACAAGCATCTGAAC |

| Alternate-splice exon 24a: | |

| 24aF | GCAGATGCCCTTAAATGTCTTT |

| 24aR | CTTCCACTCTTTTGGCAATAAAAC |

| Exon 24: | |

| 24F | TGTTTTTCCAATAAAATGGCATGA |

| 24R | CAATGGCACTGTAACTATAACCA |

| Exon 25: | |

| 25F | GGAAGTGAATGTTGGGGGTTTTC |

| 25R | AAAATCTTGGACTATCAGTTATACCAT |

| Exon 26: | |

| 26F | TGCCCCTACCATCGTTGTTTTT |

| 26R | TGAACAATGAAGGATAATAAGCAT |

| Alternate-splice exon 27a: | |

| 27aF | CTGATTGAACACCAGCCTTG |

| 27aR | GAAGGGGGTCCACATTACAA |

| Exon 27: | |

| 27F | CTCCCCATTCAGGAAGTTGGTG |

| 27R | CCCCAACCATTTATCACTGCAA |

| Exon 28: | |

| 28F | CTGGCTCCTTGTTTCTGATCTT |

| 28R | CTTGCTGACCATGCTTTCCT |

| Exon 29: | |

| 29F | TTACCTGTGCTGTTGCCTGAGC |

| 29R | TGAACTCAAAGGCCACGTTGAT |

Electronic-Database Information

Accession numbers and URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- Human Genome Browser, http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/ (for human sequence [accession numbers AJ606362, AJ459825, and AK024085] and mouse sequence [accession numbers NM_026203, BB615071, and BG297436])

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for JS, NPHP, and CORS)

- Primer3, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi

- ScanProsite, http://www.expasy.org/cgi-bin/scanprosite

References

- Barkovich AJ, Hevner R, Guerrini R (1999) Syndromes of bilateral symmetrical polymicrogyria. Am J Neuroradiol 20:1814–1821 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance PF, Cavalier L, Satran D, Pellegrino JE, Koenig M, Dobyns WB (1999) Clinical nosologic and genetic aspects of Joubert and related syndromes. J Child Neurol 14:660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland RJ, Eyaid W, Collura RV, Tully LD, Hill RS, Al-Nouri D, Al-Rumayyan A, Topcu M, Gascon G, Bodell A, Shugart YY, Ruvolo M, Walsh CA (2004) Abnormal cerebellar development and axonal decussation due to mutations in AHI1 in Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet 36:1008–1013 10.1038/ng1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Keeler LC, Parisi MA, Marsh SE, Chance PF, Glass IA, Graham JM Jr, Maria BL, Barkovich AJ, Dobyns WB (2004) Molar tooth sign of the midbrain-hindbrain junction: occurrence in multiple distinct syndromes. Am J Med Genet 125A:125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet AM, Rakic P (eds) (2000) Mouse brain development. Springer, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Rensing C, Nothwang HG, Vollmer M, Adolphs J, Hanusch H, Brandis M (1997) A novel gene encoding an SH3 domain protein is mutated in nephronophthisis type 1. Nat Genet 17:149–153 10.1038/ng1097-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Hanna Z, Kaouass M, Girard L, Jolicoeur P (2002) Ahi-1, a novel gene encoding a modular protein with WD40-repeat and SH3 domains, is targeted by the Ahi-1 and Mis-2 provirus integrations. J Virol 76:9046–9059 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9046-9059.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zhao Y, Chan WY, Vercauteren S, Pang E, Kennedy S, Nicolini F, Eaves A, Eaves C (2004) Deregulated expression in Ph+ human leukemias of AHI-1, a gene activated by insertional mutagenesis in mouse models of leukemia. Blood 103:3897–3904 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeler LC, Marsh SE, Leeflang EP, Woods CG, Sztriha L, Al-Gazali L, Gururaj A, Gleeson JG (2003) Linkage analysis in families with Joubert syndrome plus oculo-renal involvement identifies the CORS2 locus on chromosome 11p12-q13.3. Am J Hum Genet 73:656–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne C, Boltshauser E, Breivik N, Gribaa M, Betard C, Barbot C, Koenig M (2004) Homozygosity mapping of a third Joubert syndrome locus to 6q23. J Med Genet 41:273–277 10.1136/jmg.2003.014787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria BL, Hoang KB, Tusa RJ, Mancuso AA, Hamed LM, Quisling RG, Hove MT, Fennell EB, Booth-Jones M, Ringdahl DM, Yachnis AT, Creel G, Frerking B (1997) “Joubert syndrome” revisited: key ocular motor signs with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. J Child Neurol 12:423–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki T, Saijoh Y, Tsuchiya K, Shirayoshi Y, Takai S, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Yamada K, Nihei H, Nakatsuji N, Overbeek PA, Hamada H, Yokoyama T (1998) Cloning of inv, a gene that controls left/right asymmetry and kidney development. Nature 395:177–181 10.1038/26006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto EA, Schermer B, Obara T, O’Toole JF, Hiller KS, Mueller AM, Ruf RG, Hoefele J, Beekmann F, Landau D, Foreman JW, Goodship JA, Strachan T, Kispert A, Wolf MT, Gagnadoux MF, Nivet H, Antignac C, Walz G, Drummond IA, Benzing T, Hildebrandt F (2003) Mutations in INVS encoding inversin cause nephronophthisis type 2, linking renal cystic disease to the function of primary cilia and left-right axis determination. Nat Genet 34:413–420 10.1038/ng1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi MA, Bennett CL, Eckert ML, Dobyns WB, Gleeson JG, Shaw DWW, McDonald R, Eddy A, Chance PF, Glass IA (2004) The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 75:82–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribacoba Montero R, Garcia Pravia C, Astudillo A, Salas Puig J (2002) Bilateral fronto-occipital polymicrogyria and epilepsy. Seizure Suppl 11:298–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saar K, Al-Gazali L, Sztriha L, Rueschendorf F, Nur-E-Kamal M, Reis A, Bayoumi R (1999) Homozygosity mapping in families with Joubert syndrome identifies a locus on chromosome 9q34.3 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet 65:1666–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva JM, Baraitser M (1992) Joubert syndrome: a review. Am J Med Genet 43:726–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satran D, Pierpont ME, Dobyns WB (1999) Cerebello-oculo-renal syndromes including Arima, Senior-Loken and COACH syndromes: more than just variants of Joubert syndrome. Am J Med Genet 86:459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente EM, Salpietro DC, Brancati F, Bertini E, Galluccio T, Tortorella G, Briuglia S, Dallapiccola B (2003) Description, nomenclature, and mapping of a novel cerebello-renal syndrome with the molar tooth malformation. Am J Hum Genet 73:663–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]