Abstract

Brazil’s Criança Feliz Program is one of the largest early childhood development home-visiting programs globally. After seven years of scaling up, implementation barriers across diverse municipality settings prevented the program from achieving the intended impact on parenting skills and child development. We conducted a program impact pathway analysis to generate a blueprint to enhance implementation quality by (1) identifying the critical quality control points that need to be monitored throughout the scaling up and (2) specifying implementation strategies for enhancing implementation quality. The program impact pathway analysis consisted of inductive and deductive coding of pre-existing retrospective (e.g. reports, and codebooks from in-depth interviews) and workshop with national team to identify the critical quality control points and corresponding implementation barriers and facilitators. The Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change taxonomy was used to specify implementation strategies facilitating the scaling up or opportunities to address barriers across critical quality control points. We identified seven critical quality control points: hiring municipal workforce; staff training; home visits; complementary multisectoral actions; municipal supervision; technical assistance and monitoring; and funding. Implementation strategies facilitating the scale-up were “providing assistance” and “supporting teams;” opportunities for enhancing implementation quality were “financial strategies” and “evaluative and iterative strategies.” Our analysis identified seven critical quality control points necessary to achieve the intended implementation and program outcomes. The combined use of the program impact pathway and the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change taxonomy generated a meaningful blueprint of implementation strategies to enhance implementation quality, which may support the sustainability of a large-scale program.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43477-024-00141-7.

Keywords: Scale-up, Sustainability, Implementation theory, Quality improvement, Low-income settings

Introduction

About 250 million children under the age of five living in low and middle-income countries are at risk of not reaching their full childhood developmental potential due to factors like poverty (Black et al., 2017a, 2017b; Britto et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2017). Brazil is a large middle-income country in South America with nearly 4.14 million people living in poverty, of which 49.9% are children between the ages of 0 and 5 years (Cardin, 2024) live across 5,570 municipalities with sharp sociodemographic inequities (Buccini et al., 2022). The Nurturing Care Framework components – good health, adequate nutrition, responsive caregiving, opportunities for early learning, and safety and security (Britto et al., 2017); provide a roadmap to integrating programs and addressing inequities that prevent children from reaching their full developmental potential. In 2016, guided by the Nurturing Care Framework and supported by national legal statutes (Brasil, 1988, 1990, 2016), the Brazilian national government began the scale-up of the Programa Criança Feliz (PCF, or ‘Happy Child Program’) (Buccini et al., 2021).

The PCF seeks to provide (1) home visits based on the Care for Child Development curriculum to foster child stimulation and responsive parenting skills (Lucas et al., 2018), and (2) complementary multisectoral actions to mitigate socio-vulnerabilities of participating families. The PCF uses a multilevel implementation strategy across the three administrative levels of the Brazilian government. The national level is responsible for funding, articulating the multisectoral approach, and coordinating the implementation by developing protocols, training, and monitoring strategies. The state level provides technical support to municipal teams. At the municipal level, teams are responsible for home visits and complementary multisectoral actions (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024).

Scale-up refers to the expansion of program coverage to broader geographic areas, to maximize reach, effectiveness, and long-term impact (Bauer et al., 2015). By 2023, the PCF had been scaled up to 3,028 municipalities (representing 54% of all municipalities in Brazil) and exceeded 57 million home visits annually. After seven years of scaling up, a two-phase implementation evaluation documented implementation barriers that led to poor fidelity, and quality of home visits, as well as a lack of complementary multisectoral actions (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024). These implementation barriers, to a large extent, have prevented PCF from achieving the intended impact on parenting skills and child development under routine operating conditions (Santos et al., 2022).

As PCF begins the second scaling-up phase, we hypothesized that implementation science methods such as the program impact pathway (PIP) could inform quality improvements to optimize implementation strategies (i.e., activities used to enhance program adoption, implementation, and sustainability (Proctor et al., 2011)) that are not working well (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024). PIP is an approach to identify and monitor implementation pathways (i.e., the sequence of program activities and how they are expected to be delivered to achieve program impact (Scheirer, 1987)). The PIP analysis derives from “intimate knowledge of the program” obtained during interviews with implementers and program participants (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014). By expanding upon a dynamic logic diagram for program implementation, researchers and implementers can visualize from start to finish the pathways through which an effective program could be delivered (Avula et al., 2013; Buccini et al., 2019; Melo et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2014). The ultimate goal of the PIP analysis is to identify critical quality control points (CQCP) that must be monitored to detect factors that promote or hinder a program from being delivered properly and achieving intended outcomes (Buccini et al., 2019). Thus, we conducted a PIP analysis to generate a blueprint to enhance PCF implementation quality by (1) identifying CQCPs that need to be monitored throughout the scaling-up, and (2) specifying implementation strategies for enhancing implementation quality of a large-scale program.

Methods

This qualitative case study assessing PCF implementation pathways received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Institute of the São Paulo State Health Department (n. 3.320.733) and by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (n. 1,702,327–2). Additional approvals were granted by the research committees of the participating municipalities and departments. All participants provided verbal informed consent following a description of the study’s purpose and design. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) to report the study findings in this manuscript (Online Resource 1).

Research Team Positionality

The research team consisted of two PhDs faculty researchers at U.S higher education institutions (GB, RPE) and three graduate research assistants (KC, RD, LG) receiving their training in public health. They all had prior training in qualitative and implementation science research and two of them have advanced training in early childhood development (GB, RPE). Additional information on the research team positionality is provided below.

Frameworks

Program Impact Pathways (PIP)

We used the PIP program evaluation approach to systematically map PCF implementation pathways by assessing the mediating activities between program inputs, delivery, and outcomes following a causal logic, while also accounting for the contextual factors that might influence the effectiveness of the intervention (Rogers, 2002). With input from key actors, the PIP diagram mapped the planned activities and conceptualized outcomes from the national, state, and municipal levels by which the PCF intends to achieve implementation, program, and impact outcomes. The logical sequence of the PIP diagram included five domains: (a) Program initiation consists of the inputs or components that must be in place at the three levels of government (national, state, municipal) to start PCF implementation; (b) Program delivery involves the planned activities and processes to deliver the PCF; (c) Implementation outcomes entails conceptualizing short-term goals according to the implementation outcomes framework (Proctor et al., 2011); (d) Program outcomes focuses on conceptualized intermediate-term goals; and (e) Impact outcome encompasses long-term goals. Using the PIP framework, we identified CQCPs that should be monitored to detect challenges and address them in time to maximize the impact of the PCF. Barriers and facilitators related to CQCPs were systematically identified. The analytical approach is detailed below.

Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (ERIC)

The ERIC taxonomy outlines a compilation of 73 implementation strategies grouped into nine content-related categories: using evaluative and iterative strategies; providing interactive assistance; adapting and tailoring to context; developing stakeholder interrelationships; training and educating stakeholders; supporting teams; utilizing financial strategies; changing the infrastructure; and engaging the demand side (Powell et al., 2015; Waltz et al., 2015). In our study, the barriers and facilitators within each CQCP were coded following the nine categories proposed by the ERIC (see definitions adapted to the context of the PCF in Online Resource 2).

Data Sources

Retrospective Data

Retrospective data included pre-existing (1) PCF official documents (e.g., legislation, regulations, laws, decrees, bills), national-level standard operational manuals (municipal implementation guide, training manuals, monitoring manuals) (see Online Resource 3); (2) reports from evaluations on PCF implementation commissioned by the Ministry of Citizenship including (i) an assessment of the PCF implementation in 15 municipalities across Brazilian regions, (ii) an assessment of PCF implementation in 9 municipalities across the state of Goiás, located in the Western-Central Brazil, and (iii) an assessment of management and monitoring practices within the PCF across Brazil; and, (3) databases on our team’s two-phase implementation evaluation of barriers and facilitators to scale-up the PCF (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024). This included results from interviews with 22 with state-national level PCF team members conducted between October 2019 to January 2020 (Buccini et al., 2021), and 244 interviews with municipal-level PCF members (n = 132 supervisors/home visitors, n = 17 managers involved in the multisectoral implementation of the PCF, and n = 95 families participating in the program for at least 6 months) conducted between June 2021 to May 2022 (Buccini et al., 2024). In both evaluations, participants were eligible if they worked or participated in the PCF for at least 6 months. The individual interviews were conducted by two co-authors (GB and LG), who are trained in public health with experience in qualitative interviews and implementation science research. Participants were told the goals of the study and interviews lasted about 40–70 min each, were audio recorded with permission, and transcribed verbatim by a professional Portuguese speaking service. No participant refused to participate in the study. Data collection concluded when thematic saturation was achieved, which was defined as no new barriers and facilitators identified in four consecutive interviews. Barriers and facilitators were coded across the RE-AIM dimensions (Reach, Effectiveness or Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) (Holtrop et al., 2021). A full description of the participant characteristics, the interview guide, and the data management process are published elsewhere (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024).

Workshop Data

Workshop data included verbatim transcripts of one session conducted with a purposive sample of eight (n = 8) members of the PCF national coordination team working in different PCF departments (e.g., training, monitoring, articulation with states, and research). Eligibility criteria were (1) the member should have been working in the PCF implementation for at least six months, and (2) the member was available to participate in a four-hour workshop session.

Workshop is a participatory data collection approach that has been used successfully to consult and collaborate with implementers to generate reflection, and meaningful insights on program implementation pathways (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014). In this study, the workshop consisted of a highly iterative group discussion and feedback following a methodology previously used to engage participants in the PIP analysis (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2014). In brief, one co-author (GB), who is a female faculty member and native Portuguese speaker, moderated the workshop. She had prior in-depth knowledge of the CF program as well as a prior professional relationship with some of the participants, which facilitated high attendance in the workshop session. Participants were explained the goals of the study prior to the workshop. The workshop began with a presentation of the PIP diagram to the national coordination team. After the presentation, participants were invited to provide feedback, followed by a discussion of the activities outlined. The goals of the discussion were to expand the group’s understanding of program implementation aspects, integrate diverse points of view, and reach consensus on program implementation needed generate the revised PIP. The virtual workshop took place in November 2020 and lasted four hours. The workshop was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. After the workshop, a report with the revised PIP was shared with participants for further feedback. Participants reviewed the report and no new insights were elicited. Thus, one workshop session was deemed sufficient to develop the PIP diagram integrating the national implementation team’s views on the program implementation.

PIP Analyses

The PIP analyses integrated retrospective and workshop data in four steps. The first two steps determined PCF implementation theory, and the last two determined PCF implementation pathways, including barriers and facilitators (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Steps to integrate mixed methods data into the program impact pathways (PIP) analysis

Step 1–Initial PIP

Using an inductive approach, we coded retrospective information from PCF official documents across the five PIP dimensions defined in the framework section (see Online Resource 3). The coded material generated an initial PIP diagram.

Step 2–Revised PIP

Through a deductive approach, we coded retrospective PCF evaluation documents to expand, detail, and revise the dimensions of the PIP diagram. At this step, a narrative description of the PIP was developed.

Step 3–Identifying the CQCPs

Transcripts from the workshop conducted with the implementation team members were reviewed by two co-authors (KC, GB). Using a combination of inductive and deductive coding approaches, we mapped the (a) CQCPs that need to be monitored to ensure the implementation quality of PCF services, (b) facilitators and barriers across CQCPs (see Online Resource 4), and (c) intended implementation outcomes guided by the dimensions of the RE-AIM framework (Holtrop et al., 2021). Any disagreements during the coding process were resolved by consensus.

Step 4–Opportunities for Enhancing Implementation Quality

Using the nine categories from the ERIC taxonomy (Waltz et al., 2015), facilitators and barriers within each CQCP were independently coded by two co-authors (LG, GB). At the end of this step, we described ERIC categories and discrete strategies facilitating as well as opportunities to address barriers that can help improve the implementation quality.

Results

PCF Implementation Analysis

Table 1 outlines the actors and planned activities across program components: (a) Program initiation begins with the responsibilities of the PCF National Coordination Team, which includes coordination and funding, as well as formulation of the initial PCF staff training based on the Care for Child Development curriculum through a training cascade. These components connect with activities developed at the state level, such as technical assistance to monitor the quality of municipal activities. At the municipal level, the Social Assistance Secretary develops a municipal-level implementation plan and applies for national funding; (b) Program delivery starts when the national funding is approved and the municipal team (municipal coordinator, supervisors, home visitors) is hired. Municipal resources are also allocated to the PCF, which may include transportation, coordination with other sectors, organization of training, delivery of home visits, multisectoral approach, and monitoring. The monthly agreed-upon home visit target goals were identified as a critical feedback loop for national funding and program continuation (see PIP diagram in Online Resource 5).

Table 1.

Program impact pathway analysis: program components, actors, and planned activities

| Program Components | Actors | Planned activities |

|---|---|---|

| Program Initiation | PCF national team | Coordination, training, monitoring, dissemination, funding |

| Initial funding to state and municipalities | ||

| Monthly funding based on upon-agreed target goals | ||

| Initial training curriculum (80-h) | ||

| Initial and continuing education through a virtual platform | ||

| National multisectoral committee | Establish national standards for multisectoral approach | |

| State multisectoral committee | State Multisectoral Actions Plan | |

| PCF state team | State provides technical assistance and monitors municipalities | |

| Municipal social assistance secretary | Municipality enrolls in the PCF by submitting an implementation plan and allocating municipal resources to deliver the program | |

| Hiring PCF municipal team, including coordinator (optional), supervisor, and home visitors | ||

| Municipal multisectoral committee | Representation of diverse sectors and meeting regularly | |

| Develop multisectoral referral protocols and criteria | ||

| Program Delivery | National and state training cascade facilitators | Deliver and support the scale up of the initial training across municipalities in a timely manner |

| Municipal PCF coordinator | Inputting data on the e-PCF monitoring system | |

| Municipal PCF supervisors | Supervisor reviews case notes and provides supportive supervision | |

| Supervisor supports home visitor to develop multisectoral actions and communicates with other social assistance services | ||

| Municipal PCF home visitors | Home visitor delivers visits with high-fidelity | |

| Home visitor identifies family social determinants of health | ||

| Eligible families | Families enrolled in PCF | |

| Families receive an adequate number of home visits |

Implementation outcomes include the adoption of the PCF by municipalities, reaching the monthly home visit goals, high-quality training, high-quality home visits (fidelity and frequency), and effective coordination of complementary multisectoral actions. Program outcomes include decreasing family vulnerabilities while increasing parenting skills; finally the program impact goal is improving early childhood development (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Program impact pathway analysis: intended outcomes by level, indicators, and definitions

| Level | Indicators | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation | Adoption | Number of eligible municipalities adopting the PCF |

| Reach | Municipalities reaching monthly home visits target goals | |

| Sustainability | Length of program continuation in years & plans for sustainability | |

| Implementation | Timely initial training promotes desired skill set on the PCF municipal team | |

| High-quality supervision supports home visiting and multisectoral actions | ||

| Fidelity of home visits (high quality + adequate frequency of home visits) | ||

| Multisectoral plan to address social determinants of health of participating families | ||

| Program | Effectiveness | Decrease social determinants of health of participating families |

| Improvement in parenting skills | ||

| Perceived benefits and family satisfaction | ||

| Impact | Effectiveness | Improve early childhood developmental milestones |

PCF Implementation Blueprint

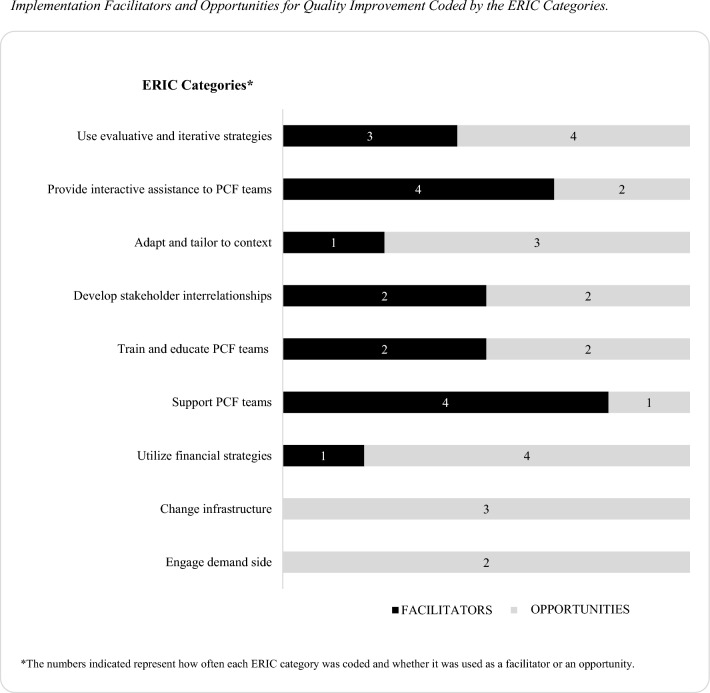

Through the PIP analysis, we identified seven CQCP implementation pathways: hiring municipal workforce; staff training; home visits; complementary multisectoral actions; municipal supervision; technical assistance and monitoring; and funding (see PIP diagram in Online Resource 5). Facilitators across CQCP and corresponding ERIC implementation strategy categories are outlined in Table 3 (see narrative in Online Resource 4). The most common implementation strategy categories facilitating PCF scale-up were “providing assistance” (n = 4) and “supporting PCF teams” (n = 4). Examples of discrete strategies used within the PCF included providing supportive supervision to facilitate the delivery of high-quality home visits (CQCP 6) as well as on-the-job training and job aids to influence the knowledge and beliefs of supervisors and home visitors (CQCP 5) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Critical quality control points in scale-up: facilitators

| Critical quality control points (CQCP) | Facilitators | ERIC categories | Discrete implementation strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| CQCP 1 Hiring municipal workforce | Demand from municipalities for technical assistance and monitoring | Provide interactive assistance to PCF teams |

Centralize technical assistance Provide local technical assistance |

| Qualified workforce to meet population demand | Support PCF teams | Revise professional roles | |

|

CQCP 2 TRAINING |

Standardized 80-h training package and evidence-based manuals UNICEF/WHO CCD curriculum and the official home visiting guide | Train and educate PCF teams |

Develop educational materials Distribute educational materials |

| Cascade training promotes efficiency and is cost-effective | Use train-the-trainer strategies | ||

| Training is provided in person and through a virtual platform |

Plan for and conduct training in an ongoing way Make training dynamic |

||

|

CQCP 3 Home Visit |

Supportive supervision is conducive to the delivery of high-quality home visit | Provide interactive assistance to PCF teams | Provide supervision |

| Home visitors’ ability to adapt to the family context enlarging outlook | Adapt and tailor to context |

Promote adaptability Tailor strategies |

|

| Ability to strengthen community resources and connections | Develop stakeholder interrelationships |

Build a coalition Promote network weaving |

|

| CQCP 4 Complementary Multisectoral Actions | Integration with social services allows municipalities to strengthen community resources and connections through the social services reference center (CRAS) | Develop stakeholder interrelationships |

Build a coalition Promote network weaving |

| Continuity of care beyond home visits reinforces engagement among the sectors | Obtain formal commitments | ||

| Coordination with existing early childhood programs | Support PCF teams | Develop resource-sharing agreements | |

| Prioritize community needs and develop multisectoral actions | Use evaluative and iterative strategies | Conduct local needs assessment | |

| High-quality supervision is conducive to referrals to other social services | Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring | ||

|

CQCP 5 Municipal Supervision |

Qualified supervisors contribute to the fidelity of supportive monitoring and evaluation | Provide interactive assistance to PCF teams | Provide supervision |

| On-the-job training and experience aids in the development of supervisor & home visitor knowledge and beliefs | Support PCF teams | Make training dynamic | |

| Real-time data collection on the level and quality of supervision reinforces long-term effectiveness on parenting and ECD outcomes | Facilitate relay of data to PCF teams | ||

| Real-time data collection on family skills and child development | |||

| Monitoring and evaluation create opportunities for quality improvement and evaluations | Use evaluative and iterative strategies | Purposefully reexamine the implementation | |

| CQCP 6 Technical Assistance and Monitoring | High-quality supervision is conducive to technical assistance and monitoring of home visits | Provide interactive assistance to PCF teams | Provide supervision |

| Supervisor & Home Visitor’s self-efficacy, knowledge, and beliefs about PCF | Support PCF teams | Revise professional roles | |

| Defined process indicators to monitor implementation using the e-PCF system | Use evaluative and iterative strategies |

Develop and organize quality monitoring systems Conduct local needs assessment |

|

| Systematic monitoring of implementation and adaptations in the delivery of PCF due to different community’s needs | |||

| Creates opportunities for qualitative research and evaluation | Purposefully reexamine the implementation | ||

| The municipal team monitors and evaluates the effectiveness of improvements in parenting skills and ECD outcomes | Develop and organize quality monitoring systems | ||

|

CQCP 7 Funding |

Federal funding | Utilize financial strategies | Access new funding |

| Federal criteria to meet federal funding | Use capitated payments |

Barriers across CQCP and corresponding implementation strategies to address them are outlined in Table 4 (see narrative in Online Resource 4). Opportunities for enhancing implementation quality included the “use of evaluative and iterative strategies” (n = 4) and the “use of financial strategies” (n = 4 across) (Table 4). Examples of discrete strategies that could be used within the PCF to enhance implementation quality were the development of a formal implementation blueprint to clarify the role of each sector in the multisectoral approach (CQCP 4) and additional funds to hire and retain PCF municipal teams with higher salaries and better work conditions (CQCP 1). Strategies within the categories “changes in infrastructure” and “engaging consumer strategies” were not used during PCF implementation, but they were considered opportunities for enhancing the quality of the implementation (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Critical quality control points in scale-up: barriers and opportunities

| Critical quality control points (CQCP) | Barriers | Government Level | Opportunities to address barriers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERIC Categories | Discrete Implementation Strategies | |||

|

CQCP 1 Hiring Municipal Workforce |

Underfund for hiring PCF municipal teams has led to low salaries and short-term contracts, and ultimately high staff turnover | Municipal | Utilize financial strategies | Fund and contract for the clinical innovation |

|

CQCP 2 Training |

Training materials lack adaptation to the different needs across the training cascade | National to municipal | Adapt and tailor to context |

Tailor strategies Promote adaptability |

| Initial training delivery through training cascade and online platform is not monitored through standardized tools and their quality, fidelity, and effectiveness are unknown | National to municipal | Use evaluative and iterative strategies |

Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring Develop and organize a quality monitoring system |

|

| PCF municipal teams lack structure and resources such as access to computers and high-speed internet to access online training | Municipal | Change Infrastructure | Change physical structure and equipment | |

| PCF municipal teams lack protected time to access online training platform courses | Municipal | Develop stakeholder interrelationships | Organize protected time for training | |

| PCF municipal teams are receiving initial training late initial due to high staff turnover | Municipal | Train and educate stakeholders | Conduct ongoing training | |

| Undertrained home visitors make shortcut adaptations to the CCD curriculum compromising the quality of home visits | Municipal | Conduct educational outreach visits | ||

|

CQCP 3 Home Visit |

Home visitors lack the means (e.g., transportation for long distances) to conduct home visits | Municipal | Change Infrastructure | Change physical structure and equipment |

| COVID-19 forced in-person home visits to be conducted virtually (e.g., WhatsApp) | National to municipal | Adapt and tailor to context |

Tailor strategies Promote adaptability |

|

|

CQCP 4 Complementary Multisectoral Actions |

Multisectoral Management Committees (MMC) are not functioning | National to municipal | Develop stakeholder interrelationships |

Build a coalition Promote network weaving Recruit, designate, and train for leadership |

| Utilize financial strategies | Use other payment schemes | |||

| Unclear role of each sector in developing complementary multisectoral actions | National to municipal | Develop stakeholder interrelationships | Obtain formal commitments | |

| Use evaluative and iterative strategies | Develop a formal implementation blueprint | |||

| National and states have failed to support municipalities in developing their municipal multisectoral action plan | National and State | Provide interactive assistance |

Provide local technical assistance Facilitation |

|

| Municipal teams lack the skills and knowledge to identify social determinants of health | Municipal | Engage participants families |

Involve patients/consumers and family members Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants |

|

| Adapt and tailor to context | Promote adaptability | |||

| Train and educate stakeholders | Conduct educational outreach visits | |||

| CQCP 5 Municipal Supervision | Supervisors are not conducting field supervision due to administrative burdens (e.g., weekly reports, input data into e-PCF) | Municipal | Provide interactive assistance |

Provide local technical assistance Facilitation |

| Supervisors lack standardized checklists or data collection tools to document the quality of supervision | Municipal | Use evaluative and iterative strategies |

Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring Develop and organize a quality monitoring system |

|

| The supervisor has a high caseload to supervise which makes effective supervision challenging | Municipal | Support PCF teams | Revise professional roles | |

| CQCP 6 Technical Assistance and Monitoring | Lack of process indicators to monitor and evaluate the scale up of the CCPs | National | Use evaluative and iterative strategies |

Purposefully reexamine the implementation Develop a formal implementation blueprint |

| The number of professionals in the state teams is limited to providing technical support to all municipalities | State | Utilize financial strategies | Fund and contract for the clinical innovation | |

| Lack of infrastructure, effective training, and technology (Wi-Fi, computer systems, etc.) needed to implement electronic monitoring system (e-PCF) | State and Municipal | Change Infrastructure |

Change physical structure and equipment Change record systems |

|

| e-PCF monitoring system instability and errors lead to delays in registering home visits | ||||

|

CQCP 7 Funding |

Municipalities are expected to co-finance, which leads to inconsistent municipal funding and uncertainty about the sustainability of PCF | National to municipal | Utilize financial strategies |

Access new funding Alter incentive/allowance structures Use other payment schemes |

| Engage participants families | Increase demand | |||

The Fig. 2 summarizes the implementation strategy categories that were coded the most and the least across facilitators and opportunities to address program operational barriers.

Fig. 2.

Implementation facilitators and opportunities for quality improvement coded by the ERIC categories

Discussion

The PIP analysis laid the implementation pathways of a complex large-scale early childhood development intervention in Brazil, creating a robust map of the barriers and facilitators to implementation quality. Our approach of combining the PIP framework with the ERIC taxonomy was a suitable methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint to enhance the implementation quality of a large-scale program. Indeed, our approach responds to the call of implementation scientists by exemplifying accessible methods for tailoring implementation blueprints in interventions with complex implementation pathways (Lewis et al., 2018). The application of ERIC allowed the identification of implementation strategies such as using evaluative iterative strategies, adapting and tailoring the delivery of the PCF to the local context, and utilizing financial strategies to address implementation barriers. Likewise, changing infrastructure and engaging the demand side were identified as underutilized strategies that could be employed to overcome persisting implementation barriers to PCF adoption and reach, respectively. Nonetheless, our study provides insights into how the purposive selection of implementation strategies can be used to address implementation barriers and enhance implementation quality, which may promote the sustainability of large-scale programs in lower-income settings.

Our findings suggested that seven CQCP implementation pathways including training, hiring, home visits, complementary actions, supervision, technical assistance and monitoring, and funding must be well coordinated to successfully scale-up the PCF. The CQCPs identified in our analysis are similar to the building blocks of implementation outlined in a recent scoping review on the scale-up pathways of nurturing care programs using the Care for Child Development curriculum in low- and middle-income countries (Buccini et al., 2023). Additionally, our PIP analysis is the first to intentionally define key implementation outcomes using the robust RE-AIM framework. The lack of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) implementation outcomes challenges monitoring the progress toward success of efforts to implement programs (Proctor et al., 2011, 2023). This might explain why the PCF under real-world conditions did not achieve its intended long-term impact on responsive interaction and early childhood development (Santos et al., 2022). Moving forward, we strongly recommend that the PCF routinely tracks the CQCP implementation pathways through monitoring and evaluation systems guided by SMART indicators to sustain quality or make corrective actions in a timely way.

Matching barriers and facilitators with implementation strategies guided by the ERIC taxonomy helped elucidate why key implementation outcomes have not been properly achieved in the PCF. This approach helped identify opportunities to overcome persisting PCF implementation barriers. Specifically, the lack of intentional change in infrastructure identified in our study may explain initial barriers to adoption by the social assistance sector. On the other hand, using strategies from the ERIC categories such as “providing assistance” and “supporting PCF teams” may reflect efforts to address barriers to adoption at the municipal level. Adoption barriers were mainly due to the top-down approach and the lack of PCF integration in the social assistance sector (Buccini et al., 2021). The extensive use of these strategy categories helped to reduce resistance and promoted a smoother adoption of PCF by the social assistance staff (Buccini et al., 2024). Likewise, the lack of engagement with the demand side identified in our study may explain persisting barriers to reaching the target goals of participating families. Evidence suggests that early childhood development programs that do not engage with the demand side leave out critical contextual affordances of the environment in which a family lives, such as cultural norms and attitudes, family resources and barriers, disposition, education, and competencies (Hackett et al., 2021; Rojas et al., 2022). While the literature acknowledges that critical components of early childhood development programs can work across various contexts and cultures without major adaptations (Ahun et al., 2023; Britto et al., 2022; Buccini et al., 2023), engaging with the demand side and learning their characteristics may be key to enhancing uptake, engagement, and retention, which in turn are prerequisites to program scale-up (Britto et al., 2022; Buccini et al., 2023). In addition, our study identified opportunities to address existing barriers, the intentional utilization of adapting and tailoring strategies to support consistent adaptations to different contexts considering the interplay between program supply and demand to support sustainability (Britto et al., 2022) and promote equity (Shelton et al., 2020).

Challenges to achieving the monthly agreed-upon home visits to meet the PCF targets were identified as critical for funding and program continuation. At the municipal level, not achieving the monthly agreed-upon home visits meant receiving lower funding resources, which in turn generated stress and pressure on supervisors and home visitors in two ways: first, the feeling of being blamed for not achieving the goals, and second, concerns about their contracts being terminated at any time. These stressors need to be addressed as they may contribute to high staff rotation, which is very costly due to the additional training capacity and resources needed and may compromise the quality of home visits and the achievement of the monthly agreed-upon home visit goals. These findings corroborate studies documenting challenges in scaling up early childhood development programs in middle and low-income countries (Britto et al., 2014). Indeed, the lack of sustainable funding has been identified as the most reported barrier to sustainability for implementing early childhood development programs in low- and middle-income countries (Ahun et al., 2023; Buccini et al., 2023; Cavallera et al., 2019; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2018; Torres et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, our analysis identified opportunities to address these implementation barriers by utilizing financial strategies, including the use of different payment schemes and the alteration of incentive/allowance structures to improve the sustainability of large-scale early childhood development programs. For example, the utilization of financial strategies along with facilitation strategies identified in our study, such as building local-level coalitions of multisectoral organizations to define roles and goals to address the social needs of vulnerable families, could facilitate cross-sectoral governance and build the nurturing care multisectoral approach missing in the PCF. Lack of multisectoral coordination has previously been identified as a major barrier to proper implementation and scale-up of early childhood development programs (Cavallera et al., 2019; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2018; Torres et al., 2018). Therefore, purposely using implementation strategies to coordinate efforts across existing Brazilian programs could benefit the operationalization of the complementary multisectoral actions to mitigate socio-vulnerabilities of participating families, which has been a major barrier that undermines PCF effectiveness.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths and limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. This in-depth case study of the PCF in Brazil triangulates data from several sources to understand how to improve its implementation at scale. The extensive retrospective data from interviews with key informants at the national, state, and municipal levels and the in-depth knowledge of the researchers gained over five years of engaging with PCF teams supported the identification of program barriers and facilitators using the ERIC taxonomy. Our data captured the perceived barriers and facilitators to participate in PCF from the perspective of 95 families across five municipalities (Buccini et al., 2024; Dos Santos et al., 2023), which is an important strength of the study. In the past, many implementation evaluations have overlooked the program participants’ points of view, which is unfortunate as the participants first-hand experiences with a program are essential for understanding effectiveness and identifying areas for improvement (Metz et al., 2024). Therefore, the combined use of retrospective and workshop data allowed the mapping of persisting barriers during PCF scaling up from multiple perspectives (Buccini et al., 2021, 2024).

Although our PIP analysis has been discussed and received feedback from the PCF team at the national level, it has not been formally discussed with teams at the state and municipal levels. Hence, the strategies to enhance implementation quality identified in our study should be interpreted cautiously. Especially because our findings are limited to the national rather than the local perspective in a large country characterized by sharp socio-demographic inequalities (Buccini et al., 2022). We acknowledge that implementing the PCF in different contexts such as the suburb of São Paulo, a Rio de Janeiro "favela", the rural interior of Goiás, or the hinterlands of Piauí would likely entail distinct implementation strategies. Indeed, the adaptation of ECD programs to the local context has been found a critical and dynamic component for successful implementation of ECD programs globally because it interacts, influences, modifies, and facilitates or constrains the scale-up and sustainability (Buccini et al., 2023). Since contextual features are not fully controllable or predictable, future studies could use our program implementation improvement blueprint as a guide to tailor implementation strategies to municipalities’ context (e.g., rural vs urban, large vs. small population size, etc.) and empirically testing their feasibility and effectiveness.

Finally, we acknowledge that the exercise of coding barriers and facilitators within the ERIC taxonomy only captured the authors’ perspective, as it has not been confirmed or discussed with key informants working on the program nor tested in the field under real-world conditions. Therefore, some strategies listed may not feasible to be implemented due to contextual realities including the lack of funding for improving the implementation of early childhood development public policies in Brazil and beyond. We expect that our innovative methodology and findings can help improve the way large scale programs are implemented, monitored and evaluated in the future to maximize their resource use, impact, and sustainability (Habicht et al., 1999). Indeed, our PIP analysis yielded a rich and complex blueprint of implementation strategy categories for overcoming implementation barriers as well as facilitating implementation. This is responsive to what implementation scientists have argued before that targeting barriers and leveraging facilitators simultaneously is a more effective program quality improvement approach (Lewis et al., 2018). While this remains an empirical question, as part of our project written reports have been shared and debriefing meetings have been conducted to discuss these findings have been conducted with key national and municipal PCF actors and their teams. Furthermore, prior to this study, our research team engaged with PCF teams for five years while conducting our independent evaluation of PCF’s scale-up process. At each stage, our team shared the results first-hand with PCF teams to get their inputs before they were publicized. Because of this, we built a respectful and collaborative relationship with the PCF teams, despite the major changes in political and coordination leadership that occurred during this period. Thus, we expect that moving forward the implementation strategies identified in our study to be considered leverage points in the decision-making to improve the quality of the PCF as the second phase of its rolling out starts.

Although PIP analyses have been extensively used to evalutate public health and nutrition programs (Melo et al., in press), to our knowledge, this is the first study to use the PIP analysis in combination with the ERIC taxonomy to gain key insights into a blueprint of implementation strategies needed to enhance the implementation pathways of complex interventions by overcoming barriers on time. We encourage other researchers to use and build from our innovative implementation science approach to effectively scale-up and sustain large-scale programs in low-income settings.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Sonia Isoyama Venancio, Dr. Muriel Gubert, and research assistant Laura Dal’Ava dos Santos for their assistance and support during the data collection for this study.

Authors’ Contributions

GB and RPE designed the research study protocol. GB and LG conducted the interviews and document review. KS and RD engaged in data interpretation and drafting of sections of the paper supervised by GB. GB conducted the analysis and wrote the final draft of the paper. RPE revised drafts critically for intellectual contribution to the final draft. All authors approved the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R00HD097301(PI: Buccini) and U01HD115256 (PI: Buccini). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official opinion of the National Institutes of Health.

Data Availability

The de-identified data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (GB). The data are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the IRB as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

The research reported in this article received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Institute of the São Paulo State Health Department (n. 3.320.733) and by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (n. 1702327–2). Additional approvals were granted by the research committees of the participating municipalities and departments.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided verbal informed consent following a description of the study’s purpose and design.

References

- Ahun, M. N., Aboud, F., Wamboldt, C., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2023). Implementation of UNICEF and WHO’s care for child development package: Lessons from a global review and key informant interviews. Frontiers in Public Health,11, 1140843. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1140843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avula, R., Menon, P., Saha, K. K., Bhuiyan, M. I., Chowdhury, A. S., Siraj, S., Haque, R., Jalal, C. S. B., Afsana, K., & Frongillo, E. A. (2013). A program impact pathway analysis identifies critical steps in the implementation and utilization of a behavior change communication intervention promoting infant and child feeding practices in Bangladesh. The Journal of Nutrition,143(12), 2029–2037. 10.3945/jn.113.179085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology,3(1), 32. 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., Fink, G., Shawar, Y. R., Shiffman, J., Devercelli, A. E., Wodon, Q. T., Vargas-Barón, E., Grantham-McGregor, S., & Committee, L. E. C. D. S. S. (2017a). Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet (London, England),389(10064), 77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., Fink, G., Shawar, Y. R., Shiffman, P. J., Devercelli, A. E., Wodon, Q. T., Vargas-Barón, E., & Grantham-McGregor, S. (2017b). Advancing early childhood development: From science to scale 1. Lancet (London, England),389(10064), 77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. https://normas.leg.br/api/binario/d9c9c09c-ee80-42c9-a327-20fd195213c7/texto

- Brasil. (1990). Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. Brasília: Ministério da Justiça. https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/crianca-e-adolescente/estatuto-da-crianca-e-do-adolescente-versao-2019.pdf

- Brasil. (2016). Senado Federal do Brasil. Avanços do Marco Legal da primeira Infância.https://www2.camara.leg.br/a-camara/estruturaadm/altosestudos/pdf/obra-avancos-do-marco-legal-da-primeira-infancia

- Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Perez-Escamilla, R., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., Bhutta, Z. A., & Early Childhood Development Interventions Review Group, for the Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee. (2017). Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet (London, England),389(10064), 91–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto, P. R., Bradley, R. H., Yoshikawa, H., Ponguta, L. A., Richter, L., & Kotler, J. A. (2022). The future of parenting programs: III uptake and scale. Parenting,22(3), 258–275. [Google Scholar]

- Britto, P. R., Yoshikawa, H., van Ravens, J., Ponguta, L. A., Reyes, M., Oh, S., Dimaya, R., Nieto, A. M., & Seder, R. (2014). Strengthening systems for integrated early childhood development services: A cross-national analysis of governance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,1308, 245–255. 10.1111/nyas.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G., Harding, K. L., Hromi‐Fiedler, A., & Pérez‐Escamilla, R. (2019). How does “Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly” work? A Programme Impact Pathways Analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(3), Article 3. 10.1111/mcn.12766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buccini, G., Coelho Kubo, S. E., Pedroso, J., Bertoldo, J., Sironi, A., Barreto, M. E., Pérez-Escamilla, R., Venancio, S. I., & Gubert, M. B. (2022). Sociodemographic inequities in nurturing care for early childhood development across Brazilian municipalities. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 10.1111/mcn.13232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G., Gubert, M. B., de AraújoPalmeira, P., Godoi, L., & Dal’Ava Dos Santos, L., Esteves, G., Venancio, S. I., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2024). Scaling up a home-visiting program for child development in Brazil: A comparative case studies analysis. Lancet Regional Health. Americas,29, 100665. 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G., Kofke, L., Case, H., Katague, M., Pacheco, M. F., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2023). Pathways to scale up early childhood programs: A scoping review of reach up and care for child development. PLOS Global Public Health,3(8), e0001542. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G., Venancio, S. I., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2021). Scaling up of Brazil’s Criança Feliz early childhood development program: An implementation science analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,1497(1), 57–73. 10.1111/nyas.14589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin, A (2024). Child Poverty in Brazil: A 2022 Overview. The Rio Times. https://www.riotimesonline.com/child-poverty-in-brazil-a-2022-overview

- Cavallera, V., Tomlinson, M., Radner, J., Coetzee, B., Daelmans, B., Hughes, R., Pérez-Escamilla, R., Silver, K. L., & Dua, T. (2019). Scaling early child development: What are the barriers and enablers? Archives of Disease in Childhood,104(Suppl 1), S43–S50. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L. M. T. D., Godoi, L., de Andrade, E., Guimarães, B., Coutinho, I. M., Pizato, N., Gonçalves, V. S. S., & Buccini, G. (2023). A qualitative analysis of the nurturing care environment of families participating in Brazil’s Criança Feliz early childhood program. PLoS ONE,18(7), e0288940. 10.1371/journal.pone.0288940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habicht, J. P., Victora, C. G., & Vaughan, J. P. (1999). Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility and probability of public health programme performance and impact. International Journal of Epidemiology,28(1), 10–18. 10.1093/ije/28.1.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, K., Proulx, K., Alvarez, A., Whiteside, P., & Omoeva, C. (2021). Case Studies of Programs to Promote and Protect Nurturing Care during the COVID 19 Pandemic. FHI360, LEGO Foundation.

- Holtrop, J. S., Estabrooks, P. A., Gaglio, B., Harden, S. M., Kessler, R. S., King, D. K., Kwan, B. M., Ory, M. G., Rabin, B. A., Shelton, R. C., & Glasgow, R. E. (2021). Understanding and applying the RE-AIM framework: Clarifications and resources. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science,5(1), e126. 10.1017/cts.2021.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. C., Scott, K., & Marriott, B. R. (2018). A methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint: An exemplar from a youth residential setting. Implementation Science: IS,13(1), 68. 10.1186/s13012-018-0761-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, J. E., Richter, L. M., & Daelmans, B. (2018). Care for child development: An intervention in support of responsive caregiving and early child development. Child: Care, Health and Development,44(1), 41–49. 10.1111/cch.12544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz, A. J., Jensen, T. M., Afkinich, J. L., Disbennett, M. E., & Farley, A. B. (2024). How the experiences of implementation support recipients contribute to implementation outcomes. Frontiers in Health Services,4, 1323807. 10.3389/frhs.2024.1323807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, D., Venancio, S., & Buccini, G. (2022). Brazilian strategy for breastfeeding and complementary feeding promotion: A program impact pathway analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,19(16), 16. 10.3390/ijerph19169839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H., Menon, P., Keithly, S. C., Kim, S. S., Hajeebhoy, N., Tran, L. M., Ruel, M. T., & Rawat, R. (2014). Program impact pathway analysis of a social franchise model shows potential to improve infant and young child feeding practices in Vietnam. The Journal of Nutrition,144(10), 1627–1636. 10.3945/jn.114.194464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R., Cavallera, V., Tomlinson, M., & Dua, T. (2018). Scaling up integrated early childhood development programs: Lessons from four countries: Scaling up of integrated early childhood development programmes. Child Care, Health and Development.10.1111/cch.12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R., Segura-Pérez, S., & Damio, G. (2014). Applying the program impact pathways (PIP) evaluation framework to school-based healthy lifestyles programs: workshop evaluation manual. Food and Nutrition Bulletin,35(3 Suppl), S97-107. 10.1177/15648265140353S202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E., Bunger, A. C., Lengnick-Hall, R., Gerke, D. R., Martin, J. K., Phillips, R. J., & Swanson, J. C. (2023). Ten years of implementation outcomes research: A scoping review. Implementation Science: IS,18(1), 31. 10.1186/s13012-023-01286-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research,38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L. M., Daelmans, B., Lombardi, J., Heymann, J., Boo, F. L., Behrman, J. R., Lu, C., Lucas, J. E., Perez-Escamilla, R., Dua, T., Bhutta, Z. A., Stenberg, K., Gertler, P., Darmstadt, G. L., & Paper 3 Working Group and the Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee. (2017). Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: Pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet (London, England),389(10064), 103–118. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P. J. (2002). Program Theory: Not Whether Programs Work but How They Work. In D. L. Stufflebeam, G. F. Madaus, & T. Kellaghan (Eds.), Evaluation Models (Vol. 49, pp. 209–232). Kluwer Academic Publishers. 10.1007/0-306-47559-6_13

- Rojas, N. M., Katter, J., Tian, R., Montesdeoca, J., Caycedo, C., & Kerker, B. D. (2022). Supporting immigrant caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Continuous adaptation and implementation of an early childhood digital engagement program. American Journal of Community Psychology,70(3–4), 407–419. 10.1002/ajcp.12616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, I. S., Munhoz, T. N., Barcelos, R. S., Blumenberg, C., Bortolotto, C. C., Matijasevich, A., Salum, C., dos Santos Júnior, H. G., Marques, L., Correia, L., de Souza, M. R., de Lira, P. I. C., Pereira, V., & Victora, C. G. (2022). Evaluation of the happy child program: A randomized study in 30 Brazilian municipalities. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva,27, 4341–4363. 10.1590/1413-812320222712.13472022EN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer, M. A. (1987). Program theory and implementation theory: Implications for evaluators. New Directions for Program Evaluation,1987(33), 59–76. 10.1002/ev.1446 [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, R. C., Chambers, D. A., & Glasgow, R. E. (2020). An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: Addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Frontiers in Public Health. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, A., Lopez Boo, F., Parra, V., Vazquez, C., Segura-Pérez, S., Cetin, Z., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2018). Chile crece contigo: Implementation, results, and scaling-up lessons. Child Care, Health and Development,44(1), 4–11. 10.1111/cch.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Matthieu, M. M., Damschroder, L. J., Chinman, M. J., Smith, J. L., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science. 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2020). Improving early childhood development: WHO guideline. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892400020986 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (GB). The data are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the IRB as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.