Macrophages and neutrophils constitutes one of the main effectors of nonspecific immunity, phagocytosing conventional and opportunistic microorganisms and presenting their antigens to T lymphocytes. This consequently induces specific immune functions (13, 91). Moreover, activated macrophages, but also phagocytosing neutrophils, produce some cytokines and other humoral mediators (e.g., defensins) that intervene in defensive and/or inflammatory processes (2, 19, 63). Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are produced by these cells in response to cytokines released by immunocompetent cells or induced by other signaling processes (23). Not only microorganisms but also viruses induce the activation of macrophages (54) and neutrophils (40). However, various viruses, analogously to some microorganisms, especially intracellular ones, can affect the regular functions of these cells. This phenomenon predisposes to different coinfections or superinfections and increases their severity (5). In addition, acquired disorders of phagocytic activity of macrophages and neutrophils of noninfective conditions, such as traumatic, dysmetabolic, and autoimmune disorders, can predispose an organism to microbial and viral infections (29).

Finally, smoking reduces the oxidative burst of monocytes and neutrophils, and increases neutrophil chemotaxis but reduces that of monocytes. Abstinence for almost 20 days repairs oxidative burst activity (93). However, monocytes/macrophages may represent an important reservoir of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (28), and other viruses, e.g., measles (85) and hepatitis C viruses (84), may propagate the infection to other target cells. Neutrophils can bind HIV-1 and transfer the infection to lymphocytic cells (35); this occurs with other viruses, for instance, in the case of cytomegalovirus infection (39).

INTERACTION OF HIV WITH MONOCYTIC AND NEUTROPHIL PHAGOCYTIC CELLS

HIV interaction with monocytes/macrophages occurs with viral envelope proteins, directly or indirectly by specific antibodies (20, 45). CD4 and chemokine receptors are implicated in virus adsorption (3), but alternative receptors such as fibronectin (100) and membrane glycolipids (89) can contribute to binding. This interaction may affect regular immune function of monocytes/macrophages (48). Some viral proteins are implicated in this phenomenon. In particular, gp 120 (77), p24 (49), and Nef (49, 82) reduce their phagocytic function and correlated activities. Instead, Tat induces alteration of trafficking (sometimes in a stimulatory way) and damages homeostasis of mononuclear phagocytes (33). Moreover, polymorphonucleated cells and especially neutrophils have the ability to bind HIV. In fact, these cells present a high level of expression of HIV-1 coreceptor CXCR4/fusin (34) and a wide repertoire of surface receptors able to recognize all macromolecule classes (37). As previously reported, these cells also have a relevant role in different aspects of nonspecific immunity, especially aging in phagocytes (37). HIV infection affects their regular functions, perhaps more easily than monocytes because of the shorter half-life of polymorphonucleated cells than of phagocytes (60).

Besides phagocytosis affecting antigen-presenting cell (APC) function, chemotaxis and cytokine production can be altered by HIV infection in both cell types (41, 42, 78).

MECHANISMS OF MONOCYTE/MACROPHAGE IMPAIRMENT INDUCED BY HIV INFECTION AND PATHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES

Lafrein et al. (57) demonstrated that HIV-1 Tat protein promotes the chemotaxis of monocytes, their adhesion to the endothelium, and their recruitment into extravascular tissues and consequently phagocytic function. This chemotactic activity modulation seems to be mediated by the Tat cysteine-rich domain (1). However, gp120 exposure also induces the macrophages to amoeboid and motile behavior (94), but downregulation of interleukin-12 (IL-12) production induced by gp120 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells interferes with Th1 differentiation and contributes to a Th2 switch (76); this glycoprotein impairs the phagosome-lysosome fusion (66).

Moreover, Nef protein can inhibit not only the macrophagic phagocytosis of infective agents (15, 82) but also that of apoptotic bodies of immune cells and in particular neutrophils, which are more easily affected by apoptotic phenomena in patients with HIV infection (101). This phenomenon may contribute to the persistence of an inflammatory state in HIV patients, especially during opportunistic infections that are often favored by defective phagocyte activity (101). The phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, although reduced in HIV-positive patients, may, however, increase HIV-1 replication in macrophages (59), thus creating a dangerous synergism with the previously reported inhibitory phenomena.

Alterations of mononuclear phagocyte function seem to be implicated in the neuropathogenic manifestations accompanying HIV-1 infection. In fact, the neuroinflammatory phenomena that particularly characterize the HIV-1 dementia complex may occur both because of the anomalous activation of brain phagocytes with production of proinflammatory cytokines and/or in consequence of the dysfunction of phagocytosis and intracellular killing of opportunistic neurotropic agents (50, 73). Pu et al. (80) demonstrated that HIV-1 Tat protein induces the activation of microglial and perivascular cells to proinflammatory protein production, leading to monocyte infiltration into the brain. Moreover, pathological manifestations occurring in HIV-positive patients as respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastroenteric mechanisms can have etiopathogenetic mechanisms similar to those described for the central nervous system (17, 50, 81, 92, 96).

As previously reported, the central role of monocyte/macrophage cells in HIV-1 infection is their expression of CD4 receptors and chemokine receptors, which allow the viral interaction. In particular, these cells are infected prevalently by macrophage-tropic strains of HIV-1; resistant to the cytopathic effect of the virus, they act as important viral reservoirs and may disseminate the infection to different tissues (50).

HIV infection affects all the immune functions of monocytes/macrophages, affecting chemotaxis (enhancement by Tat and inhibition by Nef protein), phagocytosis, intracellular killing, APC function, and cytokine production (underproduction and overproduction, according to the cytokine type) (Table 1). This impairment allows not only the establishment of various opportunistic infections, but also the reactivation of others (50). However, in early stages of HIV-1 infection, monocytic and polymorphonucleated cells phagocytose, and reactive oxygen product release can be increased, as demonstrated by Bandres et al. (4). This may be due to a nonspecific stimulation of phagocytic cells in early-phase retrovirus infection. Moreover, Pittis et al. (77) demonstrated that although the phagocytosis and the phagolysosomal dysfunction of monocytes were found at late stages of HIV infection, these phenomena are more evident when CD4+ T lymphocytes significantly decrease.

TABLE 1.

Immunologic disorders induced by HIV on monocytes and macrophages in vitro and ex vivo

| Disorder |

|---|

| Enhancement of chemotaxis by Tat and inhibition of chemotaxis by Nef protein |

| Increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1, and IL-6 |

| Inhibition of phagocytosis: inhibition of apoptotic bodies induced by Nef protein |

| Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion |

| Inhibition of antimicrobial oxygen-dependent burst and acidification, induced in part by gp120 |

| Decrease of surface expression of CD4, CD49e, and CD62L |

| Decrease of Fcγ receptor expression |

| Inhibition of production of macrophage-CSF |

| Decreased activity of APC function |

As previously recalled, in vitro studies demonstrated that, other than treatment with recombinant Nef (82), challenge with recombinant gp120 impaired macrophage activity and particularly phagolysosomal fusion at doses ranging from 1 to 1,000 ng/ml of viral protein (77). These data were confirmed by Moorjani et al. (66), who also demonstrated a defect of phagosome-lysosome fusion in blood monocyte-derived macrophages infected by HIV-1 or treated with recombinant gp120 only. These investigators suggested that this phenomenon initially depends on the interaction between the viral glycoprotein and CD4 macrophage receptor. Pietrella et al. (75) demonstrated that gp120 reduces the antifungal capacity of peripheral blood monocytes, affecting the antimicrobial oxygen-dependent burst and the phagolysosome acidification. Durrbaum-Landmann et al. (26) studied the effects of recombinant gp120 on monocyte cultures and demonstrated a significant reduction in these cells' ability to stimulate autologous lymphocytes in response to anti-CD3, accompanied by a significant decrease in CD4 and Fc receptor expression.

Kedzierska et al. (51) demonstrated that HIV-1 infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages markedly affects FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. This occurs perhaps because the infection inhibits the tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins that is necessary for the initial receptor activation, a phenomenon particularly dependent on Nef protein activity. In addition, interaction with cellular kinases, downmodulation of CD4 expression, and inhibition of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF) exerted by Nef protein on monocytes/macrophages were also described (12, 97).

Finally, Trial et al. (103) demonstrated that in HIV-1-infected patients at stage A, the percentage of monocytes expressing CD49d, HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, and CD11a/CD18 was increased. Instead, at stages B and C, when phagocytic activity and trans-endothelial migration ability were markedly depressed, surface expression of CD49e and CD62L decreased (Table 1). This happens in concomitance with the reduced percentage of monocytes expressing CD18, CD11a, CD29, CD49e, CD54, CD58, CD31, and HLA-I. This phenomenon, which particularly concerns receptors of activation and cellular adhesion, seems to depend on the presence of high levels of circulating immune complexes.

MECHANISMS OF NEUTROPHIL IMPAIRMENT INDUCED BY HIV INFECTION AND PATHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES

As previously recalled, neutrophil function can be impaired by HIV infection (4). HIV-1 produces neutrophilic damage in a direct fashion by interacting with envelope constituents in cell membranes (67). Moreover, leukopenia and neutropenia are often present in HIV-positive patients, especially when patients have been diagnosed with AIDS. Consequently, microbial infections are a common problem of in late stages of HIV infection (11). In particular, Pitrak (78) demonstrated that this retroviral infection can produce defects in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and microbial killing, especially when CD4+ T-cell levels were <200 cells/μl (Table 1). Increases in neutrophil apoptosis via Fas may worsen the biological functioning of these cells (87); this in part explains the neutropenia induced by HIV infection (11, 56). Perskvist et al. (73) noted that HIV-1 infection accelerated the apoptosis of neutrophils, especially in the presence of apoptotic infective stimuli, contributing to proinflammatory cytokine release. However, Pugliese et al. (83) previously demonstrated that Nef protein may increase the effect of apoptotic stimuli in HIV target cells.

Treatment with recombinant granulocyte-CSF and granulocyte-macrophage CSF seems to improve neutrophil defects (18, 56). On this topic, Coffey et al. (18) demonstrated that treatment with granulocyte-CSF of HIV-infected patients increases the anticryptococcal activity of neutrophils. Vecchiarelli et al. (104) observed a cytokine dysregulation of neutrophils in HIV-infected patients. Inflammatory stimuli of concomitant infections increase the binding ability of HIV-1 to neutrophils, thus facilitating the propagation of infection to other susceptible cells (36). Analogously to monocytes, decreased phagocytosis and respiratory burst of granulocytes during HIV-1 infection correlates with CD4+ T-cell concentrations (10, 25). Prakash et al. (79) demonstrated an enhancing effect of Tat protein on ethanol-induced impairment of neutrophil function with transgenic mice. Meddows-Taylor et al. (64) suggested that defects in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) in phagocytosis and oxidative burst, detected particularly in HIV-1 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, depend in part on the reduced expression of IL-8 surface receptors. In fact, both A and B IL-8 receptors considerably decrease in these cells, causing a reduced response in such cytokines implicated in neutrophil PMNL degranulation. However, in vitro treatment with IL-2 or IL-8 does not improve the phagocytic activity of these cells (47). In conclusion, we recall that neutrophil function is regulated by some cytokines (7, 27, 31) and that the cytokine network is generally altered in HIV-infected patients (95).

INTRACELLULAR MICROORGANISM PHAGOCYTOSIS AND HIV INFECTION

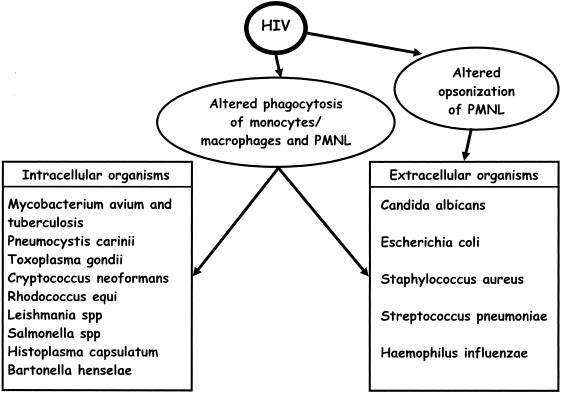

Several opportunistic and nonopportunistic intracellular microorganisms, such as Salmonellae, Mycobacteria, Toxoplasma gondii, Pneumocystis carinii, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Histoplasma capsulatum (some of these are facultative intracellular parasites), often produce serious manifestations in last stages of HIV infection (Fig. 1). More rarely, this occurs with Rhodococcus equi (responsible for pyogranulomatous bronchopneumonia) and Bartonella henselae (responsible for bacillary parenchymal angiomatosis) but also with many other infective agents (22). This happens in good part because neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages are seriously compromised in their functions (22).

FIG. 1.

Alterations of phagocytic and opsonic activities of monocytes/macrophages and PMNLs against intracellular and extracellular organisms induced by HIV.

Salmonellosis, often produced by minor salmonella strains, represents a serious problem for AIDS patients. In fact, in these patients not only major but also minor salmonella strains act as intracellular microorganisms, because of phagocytic cell defects (46).

Kedzierska et al. (49) demonstrated that the phagocytosis of intracellular opportunistic agents Mycobacterium avium complex and Toxoplasma gondii is impaired in human monocytes infected with wild-type strains of HIV-1, but not with nef gene-defective HIV-1 strains, confirming the role of this gene product in macrophagic cell inhibitory activity. Perskvist et al. (73) demonstrated a lower half-life in neutrophils in patients coinfected with HIV-Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Bonecini-Almeida Mda et al. (10) found that AIDS patients suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis have a reduced level of phagocytic activity in alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, especially when advanced impairment of CD4+ T cells was present; in addition, they demonstrated that this phenomenon is not only innate in the phagocytes of HIV-1-positive subjects but was also indirect, i.e., it is mediated by cytokine dysregulation. Denis and Ghadirian (24), comparing the bronchoalveolar lavage-derived macrophages of HIV-1 infected subjects with those of healthy individuals, showed significant alterations in some cytokine release in the case of HIV-positive patients. PMNL function is also significantly compromised during the last stages of HIV infection, particularly in the pathological association between HIV-1 and tuberculosis (91).

In regard to Pneumocystis carinii (responsible for pneumonitis in seriously immunocompromised patients), HIV-1-infected subjects show a significant reduction in macrophagic mannose receptors (especially in patients with CD4+ counts of <200 cells/mm3) with a consequent decrease in lung anti-infection protection. In fact, such receptors mediate macrophage binding and subsequent phagocytosis of this opportunistic microorganism (55). Moreover, neutrophils of HIV-positive subjects are impaired in their ability to counterattack this microorganism (58).

In addition, coinfection worsens neutrophilic impairment (36). Toxoplasma gondii is often responsible for disseminated reactivations in AIDS patients, especially in neurotoxoplasmosis (70). Peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages of healthy individuals infected with a monocytotropic strain of HIV-1 reduce their phagocytic activity against this protozoan; intracellular replication of the microorganism is enhanced by HIV infection (6). This observation postulates a suggestive mechanism of T. gondii reactivation in AIDS patients. In addition, the severity of leishmaniosis is increased by HIV infection, because the protozoan replicates easily within the macrophages of HIV-infected subjects (102).

Of particular interest is the observation of the impairment of anticryptococcal activity of peritoneal and blood-derived macrophages after in vitro infection with HIV-1, as demonstrated by Cameron et al. (14). The investigators think that this depression, induced by HIV-1, depends not only on viral tropism and replication but also on cell tissue origin. In fact, this phenomenon, restricted to phagocytic activity alone, cannot be detected in alveolar macrophages (14).

To explain the influence of HIV infection on alveolar macrophages that constitute a first barrier against Cryptococcus neoformans inhalation in immunocompetent subjects, Ieong et al. (43) performed an enlightening in vitro experimental study. These investigators demonstrated that HIV-1 infection of these cells significantly reduces or suppresses fungicidal activity against this microorganism without, however, affecting the binding or internalization of C. neoformans, only inhibiting the intracellular antimicrobial phenomena.

Monocyte-derived macrophages from HIV-infected subjects also present impaired phagocytic functions against Histoplasma capsulatum yeast and are more permissive for their intracellular replication (16). In vitro tests confirm these data and demonstrate that only infective virions can affect both phagocytic activity and intracellular killing of macrophages; instead, treatment with gp120 alone may reduce only the phagocytosis of the yeast (16).

EXTRACELLULAR MICROORGANISM PHAGOCYTOSIS AND HIV INFECTION

There is a good deal of data on phagocytosis and the impairment of intracellular killing of extracellular microorganisms in HIV-infected patients, especially in regard to yeasts.

In particular, Candida albicans opsonophagocytosis in neutrophils and intracellular killing were progressively reduced in HIV-positive subjects, in parallel with the increasing severity of viral infection (Fig. 1) (98). With this yeast, Tascini et al. (99) demonstrated that the inhibition of fungicidal activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in HIV-infected patients was due in part to IL-4 and IL-10 overproduction. In fact, these cytokines are able to impair neutrophil activity at high doses. This observation is in accord with that of Yoo et al. (106), who demonstrated alteration of cytokine equilibrium and impairment of monocyte-macrophage function in HIV infection.

Crowe et al. (21) demonstrated that HIV-1 infection of monocytic-derived macrophages decreased the percentage of Candida albicans-phagocytosing cells from 83% to 53%, and the mean number of yeasts per cell from 6.1 to 2.5. These findings and the data previously reported are in accord with the high incidence of serious candidiasis in AIDS patients. In addition, we demonstrated a significant inhibition exerted by Nef protein on Candida albicans macrophagic phagocytosis and killing, depending on oxidative processes (82). Conversely, Tat protein is able to bind Candida albicans through its RGD motif (Arg-Gly-Asp) and to induce hyphae production, a phenomenon that seems to increase the in vitro phagocytosis of the yeast (38).

In the early stages of HIV-1 infection, monocytic and PMNL phagocytosis and reactive oxygen product release can be increased, as demonstrated by Bandres et al. (4) with Staphylococcus aureus or Escherichia coli as a target. This may be in consequence of a nonspecific stimulation of phagocytic cells in the early phases of retrovirus infection. In the late stages of HIV infection, with low levels of CD4 T cells and with extracellular microorganisms present, the defensive mechanisms of monocytic/macrophagic cells and granulocytes are depressed (25). In fact, a reduced level of phagocytosis with E. coli and S. aureus was found by Schaumann et al. (88) in neutrophils of HIV-infected patients with low levels of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1).

Brettle (11) recalled that the high frequency of bacterial sepsis in HIV-positive patients depends in part on neutrophil function impairment (chemotaxis, bacterial killing, phagocytosis, and superoxide production). Payeras et al. (71) underlined the role of opsonophagocytosis defects in HIV-positive patients in facilitating encapsulation of bacteria responsible for recurrent infections of the respiratory tract.

To complete the question, we note the effects of HIV infection on microglial cells, which are very important as nonspecific immunologic defenses for the nervous system (residential macrophage functions) but which can also present a pathological activation, with release of proinflammatory cytokines in AIDS patients (68). Microglial cells and brain macrophages are susceptible to HIV-1 infection; reducing their protective activities may promote the diffusion of HIV to the central nervous system (32).

Finally, dendritic cells, a particular set of monocyte-derived cells, can also be affected by HIV infection. They may absorb, internalize, and transfer the virus to lymphocytes; in parallel, they are also damaged in their defensive functions (105).

EFFECT OF ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY ON PHAGOCYTIC CELL FUNCTION

Mastroianni et al. (62) found that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) produces a significant improvement in chemotaxis and microbicidal activity of monocytic and neutrophil cells, contributing to cell-mediated immune responses against opportunistic agents (for instance, APC function). Consequently, a correct antiretroviral treatment, possibly associated with a suitable immunotherapy and/or growth factor treatment, may improve the monocyte/macrophage and neutrophil functions, together with some correlated activities of the immune system, as underlined by various authors (52, 53, 74) This contributes to the reduction in incidence of concomitant infections, especially those produced by opportunistic microorganisms such as the Mycobacterium avium complex, Pneumocystis carinii, Toxoplasma gondii, and Candida albicans. Antiretroviral therapy may regulate cytokine production, in particular, the release of IL-12 (which modulates cell-mediated immune responses) and IL-10 (anti-inflammatory cytokine) by monocytes/macrophages (9). Of particular interest is the demonstration that indinavir (a protease inhibitor) can inhibit the production of urease and protease, virulence factors of Cryptococcus neoformans but also involved in capsule formation, which contributes to reducing the risk of this serious opportunistic infection in AIDS patients (65). Blasi et al. (8) found that the same antiretroviral drug increases Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis and killing produced by microglial cells. Nathoo et al. (69) demonstrated that the treatment with protease inhibitors increases nonopsonic macrophagic phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in HIV-1 patients with malaria.

Magnani et al. (61) suggested the use of a potent antiviral drug, such as the antileukemic fludarabine (9-β-d-arabinofurasonyl-2-fluoroadenine 5′-monophosphate) loaded to red blood cells for the eradication of HIV-1 in macrophagic cells. This experimental therapy affects only infected macrophages, reduces the virus release from these cells, and improves their biological function.

Finally, Feldman (30) demonstrated that HAART reduces the serious risk of pneumonia by intracellular or extracellular microorganisms, not only by increasing CD4 T-cell levels but also in part by improving the activity of phagocytic cells.

CONCLUSIONS

Monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils play an important role in nonspecific immunity against opportunistic pathogens by acting as first-line defense against extracellular pathogens, especially against intracellular pathogens, which are able to survive and replicate into phagocytic cells (44). This is true in several immunodeficiency states, particularly during HIV-1 infection.

Several mechanisms are used by phagocytic cells (monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils) to inhibit bacterial replication, including APC activity, cytokine production, and more specifically phagocytosis and killing. All these mechanisms are altered in phagocytic cells from HIV-1-infected patients, particularly during the late stages of the disease, and parallel a persistent decrease in the number of CD4 T cells (86). HIV is able to decrease activity of monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils indirectly through its viral proteins, such as gp120, p24, and Nef protein (49, 77, 82). On the other hand, HIV-1 Tat protein promotes the chemotactic activity of monocytes in vitro (1, 57).

Finally, HAART is partially able to restore phagocytic activity in HIV-1-infected patients, and thus preventing or reducing opportunistic infections related to these immunologic disorders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albini, A., R. Benelli, D. Giunciuglio, T. Cai, G. Mariani, S. Ferrini, and D. M. Noonan. 1998. Identification of a novel domain of HIV Tat involved in monocyte chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:15895-15900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, J. 2005. The inflammatory reflex: introduction. J. Intern. Med. 257:122-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachrach, E., H. Dreja, Y. L. Lin, C. Mettling, V. Pinet, P. Corbeau, and M. Piechaczyk. 2005. Effects of virion surface gp120 density on infection by HIV-1 and viral production by infected cells. Virology 332:418-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandres, J. C., J. Trial, D. M. Musher, and R. D. Rossen. 1993. Increased phagocytosis and generation of reactive oxygen products by neutrophils and monocytes of men with stage 1 human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 168:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beadling, C., and M. K. Slifka. 2004. How do viral infections predispose patients to bacterial infections? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 17:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggs, B. A., M. Hewish, S. Kent, K. Hayes, and S. M. Crowe. 1995. HIV-1 infection of human macrophages impairs phagocytosis and killing of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 154:6132-6139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bittleman, D. B., R. A. Erger, and T. B. Casale. 1996. Cytokines induce selective granulocyte chemotactic responses. Inflamm. Res. 45:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasi, E., B. Colombari, C. F. Orsi, M. Pinti, L. Troiano, A. Cossarizza, R. Esposito, S. Peppoloni, C. Mussini, and R. Neglia. 2004. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitor indinavir directly affects the opportunistic fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 42:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bocchino, M., E. Ledru, T. Debord, and M. L. Gougeon. 2001. Increased priming for interleukin-12 and tumour necrosis factor alpha in CD64 monocytes in HIV infection: modulation by cytokines and therapy. AIDS 15:1213-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonecini-Almeida Mda, G., E. Werneck-Barroso, P. B. Carvalho, C. P. de Moura, E. F. Andrade, A. Hafner, C. E. Carvalho, J. L. Ho, A. L. Kritski, and M. G. Morgado. 1998. Functional activity of alveolar and peripheral cells in patients with human acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and pulmonary tuberculosis. Cell. Immunol. 190:112-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brettle, R. P. 1997. Bacterial infections in HIV: the extent and nature of the problem. Int. J. STD AIDS 8:5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, A., S. Moghaddam, T. Kawano, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2004. Multiple human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef functions contribute to efficient replication in primary human macrophages. J. Gen. Virol. 85:1463-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calandra, T. 2003. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and host innate immune responses to microbes. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 35:573-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron, M. L., D. L. Granger, T. J. Matthews, and J. B. Weinberg. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected human blood monocytes and peritoneal macrophages have reduced anticryptococcal activity, whereas HIV-infected alveolar macrophages retain normal activity. J. Infect. Dis. 170:60-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capo, C., A. Moynault, Y. Collette, D. Olive, E. J. Brown, D. Raoult, and J. L. Mege. 2003. Coxiella burnetii avoids macrophage phagocytosis by interfering with spatial distribution of complement receptor 3. J. Immunol. 170:4217-4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaturvedi, S., and S. L. Newman. 1997. Modulation of the effector function of human macrophages for Histoplasma capsulatum by HIV-1: Role of the envelope glycoprotein gp120. J. Clin. Investig. 100:1465-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi, D., J. Henry, J. Kelley, R. Thorpe, J. K. Smith, and G. Krishnaswamy. 2000. The effect of HIV infection on endothelial function. Endothelium 7:223-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coffey, M. J., S. M. Phare, S. George, M. Peters-Golden, and P. H. Kazanjian. 1998. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration to HIV-infected subjects augments reduced leukotriene synthesis and anticryptococcal activity in neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 102:663-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole, A. M., and A. J. Waring. 2002. The role of defensins in lung biology and therapy. Am. J. Respir. Med. 1:249-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conti, L., L. Fantuzzi, M. Del Corno, F. Belardelli, and S. Gessani. 2004. Immunomodulatory effects of the HIV-1 gp120 protein on antigen presenting cells: implications for AIDS pathogenesis. Immunobiology 209:99-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowe, S. M., N. J. Vardaxis, S. J. Kent, A. L. Maerz, M. J. Hewish, M. S. McGrath, and J. Mills. 1994. HIV infection of monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro reduces phagocytosis of Candida albicans. J. Leukoc. Biol. 56:318-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covelli, V., S. Pece, G. Giuliani, C. De Simone, and E. Jrillo. 1997. Pathogenetic role of phagocytic abnormalities in human virus immunodeficiency infection: possible therapeutical approaches. A review. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 19:147-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dedon, P. C., and S. R. Tannenbaum. 2004. Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423:12-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denis, M., and E. Ghadirian. 1994. Dysregulation of intereleukin 8, interleukin 10, and interleukin 12 release by alveolar macrophages from HIV type 1-infected subjects. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:1619-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobmeyer, T. S., B. Raffel, J. M. Dobmeyer, S. Findhammer, S. A. Klein, D. Kabelitz, D. Hoelzer, E. B. Helm, and R. Rossol. 1995. Decreased function of monocytes and granulocytes during HIV-1 infection correlates with CD4 cell counts. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1:9-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durrbaum-Landmann, I., E. Kaltenhauser, H. D. Flad, and M. Ernst. 1994. HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 affects phenotype and function of monocytes in vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 55:545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis, T. N., and B. L. Beaman. 2004. Interferon-gamma activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophil function. Immunology 112:2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elssner, A., J. E. Carter, T. M. Yunger, and M. D. Wewers. 2004. HIV-1 infection does not impair human alveolar macrophage phagocytic function unless combined with cigarette smoking. Chest 125:1071-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelich, G., D. G. Wright, and K. L. Hartshorn. 2001. Acquired disorders of phagocyte function complicating medical and surgical illnesses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:2040-2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman, C. 2005. Pneumonia associated with HIV infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:165-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrante, A. 1992. Activation of neutrophils by interleukins-1 and-2 and tumor necrosis factors. Immunol. Ser. 57:417-436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine, S. M., S. B. Maggirwar, P. R. Elliott, L. G. Epstein, H. A. Gelbard, and S. Dewhurst. 1999. Proteasome blockers inhibit TNF-alpha release by lipopolysaccharide stimulated macrophages and microglia: implication for HIV-1 dementia. J. Neuroimmunol. 95:55-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer-Smith, T., S. Croul, A. Adenivi, K. Rybicka, S. Morzello, K. Khalili, and J. Rappaport. 2004. Macrophage/microglial accumulation and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in the central nervous system in human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 164:2089-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forster, R., E. Kremmer, A. Schubel, D. Breitfeld, A. Kleinschmidt, C. Nerl, G. Bernhardt, and M. Lipp. 1998. Intracellular and surface expression of the HIV-1 coreceptor CXCR4/fusin on various leukocyte subsets: rapid internalization and recycling upon activation. J. Immunol. 160:1522-1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabali, A. M., J. J. Anzinger, G. T. Spear, and L. L. Thomas. 2004. Activation by inflammatory stimuli increases neutrophil binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and subsequent infection of lymphocytes. J. Virol. 78:10833-10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabrilovich, D., L. Ivanova, L. Serebrovskaya, G. Shepeleva, and V. Pokrovsky. 1994. Clinical significance of neutrophil functional activity in HIV infection. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 26:41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon, S. 2004. Pathogen recognition or homeostasis? APC receptor function in innate immunity. C. R. Biol. 327:603-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gruber, A., C. P. Lell, C. Speth, H. Stoiber, C. Lass-Florl, A. Sonneborn, J. F. Ernst, M. P. Dierich, and R. Wurzner. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat binds to Candida albicans, inducing hyphae but augmenting phagocytosis in vitro. Immunology 104:455-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grundy, J. E., K. M. Lawson, L. P. McCormac, J. M. Fletcher, and K. L. Yong. 1998. Cytomegalovirus-infected endothelial cells recruit neutrophils by the secretion of C-X-C chemokines and transmit virus by direct neutrophil-endothelial cell contact and during neutrophil transendothelial migration. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1465-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haig, D. M., and C. J. McInnes. 2002. Immunity and counter-immunity during infection with parapoxvirus orf virus. Virus Res. 88:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes, P. J., Y. M. Miao, F. M. Gotch, and B. G. Gazzard. 1999. Alterations in blood leucocyte adhesion molecule profiles in HIV-1 infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 117:331-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofman, P., F. Fischer, D. F. Far, E. Selva, V. Battaglione, J. Bayle, and B. Rossi. 1999. Impairment of HIV polymorphonuclear leukocyte transmigration across T84 cell monolayers: an alternative mechanism for increased intestinal bacterial infections in AIDS? Eur. Cytokine Netw. 10:373-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ieong, M. H., C. C. Reardon, S. M. Levitz, and H. Kornfeld. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of alveolar macrophages impairs their innate fungicidal activity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162:966-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones, T. C. 1996. The effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (rGM-CSF) on macrophage function in microbial disease. Med. Oncol. 13:141-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamara, P., L. M. Melendez-Guerrero, M. Arroyo, H. L. Weiss, and P. E. Jolly. 2005. Maternal plasma viral load and neutralizing/enhancing antibodies in vertical transmission of HIV: a non-randomized prospective study. Virol. J. 24:15-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kankwatira, A. M., G. A. Mwafulirwa, and M. A. Gordon. 2004. Non-typhoidal salmonella bacteraemia—an under-recognized feature of AIDS in African adults. Trop. Doct. 34:198-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaul, D., M. J. Coffey, S. M. Phare, and P. H. Kazanjiab. 2003. Capacity of neutrophils and monocytes from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients and healthy controls to inhibit growth of Mycobacterium bovis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 141:330-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kedzierska, K., G. Paukovics, A. Handley, M. Hewish, J. Hocking, P. U. Cameron, and S. M. Crowe. 2004. Interferon-gamma therapy activates human monocytes for enhanced phagocytosis of Mycobacterium avium complex in HIV-infected individuals. HIV Clin. Trials 5:80-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kedzierska, K., M. Churchill, C. L. Maslin, R. Azzam, P. Ellery, H. T. Chan, J. Wilson, N. J. Deacon, A. Jaworowski, and S. M. Crowe. 2003. Phagocytic efficiency of monocytes and macrophages obtained from Sydney blood bank cohort members infected with an attenuated strain of HIV-1. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 34:445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kedzierska, K., and S. M. Crowe. 2002. The role of monocytes and macrophages in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Curr. Med. Chem. 9:1893-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kedzierska, K., P. Ellery, J. Mak, S. R. Lewin, S. M. Crowe, and A. Jaworowski. 2002. HIV-1 down-modulates gamma signaling chain of Fc gamma R in human macrophages: a possible mechanism for inhibition of phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 168:2895-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kedzierska, K., J. Mak, A. Mijch, I. Cooke, M. Rainbird, S. Roberts, G. Paukovics, D. Jolley, A. Lopez, and S. M. Crowe. 2000. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor augments phagocytosis of Mycobacterium avium complex by human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected monocytes/macrophages in vitro and in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 181:390-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kedzierska, K., R. Azzam, P. Ellery, J. Mak, A. Jaworowski, and S. M. Crowe. 2003. Detective phagocytosis by human monocyte/macrophages following HIV-1 infection: underlying mechanisms and modulation by adjunctive cytokine therapy. J. Clin. Virol. 26:247-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koyama, A. H., T. Fukumori, M. Fujita, H. Irie, and A. Adachi. 2000. Physiological significance of apoptosis in animal virus infection. Microbes Infect. 2:1111-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koziel, H., Q. Eichbaum, B. A. Kruskal, P. Pinkston, R. A. Rogers, M. Y. Armstrong, F. F. Richards, R. M. Rose, and R. A. Ezekowitz. 1998. Reduced binding and phagocytosis of Pneumocystis carinii by alveolar macrophages from persons infected with HIV-1 correlates with mannose receptor downregulation. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1332-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuritzkes, D. R. 2000. Neutropenia, neutrophil dysfunction, and bacterial infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease: the role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:256-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lafrein, R. M., L. M. Wahl, J. S. Epstein, I. K. Hewlett, K. M. Yamada, and S. Dhawan. 1996. HIV-1-Tat protein promotes chemotaxis and invasive behavior by monocytes. J. Immunol. 157:974-977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laursen, A. L., J. Rungby, and P. L. Andersen. 1995. Decreased activation of the respiratory burst in neutrophils from AIDS patients with previous Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 172:497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lima, R. G., J. Van Weyenbergh, E. M. Saraiva, M. Barral-Netto, B. Galvao-Castro, and D. C. Bou-Habib. 2002. The replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in macrophages is enhanced after phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1561-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mackey, M. C., A. A. Aprikyan, and D. C. Dale. 2003. The rate of apoptosis in post mitotic neutrophil precursors on normal ands neutropenic humans. Cell Prolif. 36:27-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magnani, M., E. Balestra, A. Fraternale, S. Aquaro, M. Paiardini, B. Cervasi, A. Casabianca, E. Garaci, and C. F. Perno. 2003. Drug-loaded red blood cell-mediated clearance of HIV-1 macrophage reservoir by selective inhibition of STAT1 expression. J. Leukoc Biol. 74:764-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mastroianni, C. M., M. Lichtner, F. Mengoni, D'Agostino, C., G. Forcina, d'Ettore, G., P. Santopadre, and V. Vullo. 1999. Improvement in neutrophil and monocyte function during highly active antiretroviral treatment of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 13:883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matsukawa, A., C. M. Hogaboam, N. W. Lukacs, and S. L. Kunkel. 2000. Chemokines and innate immunity. Rev. Immunogenet. 2:339-358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meddows-Taylor, S., D. J. Martin, and C. T. Tiemessen. 1999. Impaired interleukin-8-induced degranulation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:345-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Monari, C., E. Pericolini, G. Bistoni, E. Cenci, F. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 2005. Influence of indinavir on virulence and growth of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Infect. Dis. 191:307-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moorjani, H., B. P. Craddock, S. A. Morrison, and R. T. Steigbigel. 1996. Impairment of phagosome-lysosome fusion in HIV-1 infected macrophages.J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Munoz, J. F., S. Salmen, L. R. Berrueta, M. P. Carlos, J. A. Cova, J. H. Donis, M. R. Hernandez, and J. V. Torres. 1999. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on intracellular activation and superoxide production by neutrophils. J. Infect. Dis. 180:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakamura, Y. 2002. Regulation factors for microglial activation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 25:945-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nathoo, S., L. Serghides, and K. C. Kain. 2003. Effect of HIV-1 antiretroviral drugs on cytoadherence and phagocytic clearance of Plasmodium falciparum-parasited erythrocytes. Lancet 362:1039-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nissapatorn, V., C. Lee, K. F. Quek, C. L. Leong, R. Mahmud, and K. A. Abdullah. 2004. Toxoplasmosis in HIV/AIDS patients: a current situation. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57:160-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Payeras, A., P. Martinez, J. Mila, M. Riera, A. Pareja, J. Casal, and N. Matamoros. 2002. Risk factors in HIV-1 infected patients developing repetitive bacterial infections: toxicological, clinical, aspecific antibody class responses, opsonophagocytosis and Fcγ RIIa polymorhism characteristics. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:271-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Persidsky, Y., and H. E. Gendelman. 2003. Mononuclear phagocyte immunity and the neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:691-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perskvist, N., M. Long, O. Stendahl, and L. Zheng. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes apoptosis in human neutrophils by activating capsase-3 and altering expression of Bax/Bcl-xL via an oxygen-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 168:6358-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pett, S. L., and A. D. Kelleher. 2003. Cytokine therapies in HIV-1 infection: present and future. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 1:83-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pietrella, D., C. Monari, C. Retini, B. Palazzetti, F. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein gp120 impairs intracellular antifungal mechanisms in human monocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 177:347-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pietrella, D., T. R. Kozel, C. Monari, F. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 2001. Interleukin-12 counterbalances the deleterious effect of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 on the immune response to Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Infect. Dis. 183:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pittis, M. G., G. Sternik, L. Sen, R. A. Diez, N. Planes, D. Pirola, and M. E. Estevez. 1993. Impaired phagolysosomal fusion peripheral blood monocytes from HIV-1 infected subjects. Scand. J. Immunol. 38:423-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pitrak, D. L. 1999. Neutrophil deficiency and dysfunction in HIV-infected patients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 56(S5):9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prakash, O., P. Zhang, M. Xie, M. Ali, P. Zhou, R. Coleman, D. A. Stoltz, G. J. Bagdy, J. E. Shellito, and S. Nelson. 1998. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein potentiates ethanol-induced neutrophil functional impairment in transgenic mice. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 22:2043-2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pu, H., J. Tian, G. Flora, Y. W. Lee, A. Nath, B. Hennig, and M. Toborek. 2003. HIV-1 Tat protein upregulates inflammatory mediators and induces monocyte invasion into the brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 24:224-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pugliese, A., L. Gennero, V. Vidotto, T. Beltramo, S. Petrini, and D. Torre. 2004. A review of cardiovascular complications accompanying AIDS. Cell Biochem. Funct. 22:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pugliese, A., D. Torre, F. M. Baccino, G. Di Perri, C. Cantamessa, L. Gerbaudo, A. Saini, and V. Vidotto. 2000. Candida albicans and HIV-1 infection. Cell Biochem. Funct. 18:235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pugliese, A., C. Cantamessa, A. Saini, A. Piragino, L. Gennero, C. Martini, and D. Torre. 1999. Effects of the exogenous Nef protein on HIV-1 target cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 17:183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Radkowski, M., J. F. Gallegos-Orozco, J. Jablonska, T. V. Colby, B. Walewska-Zielecka, J. Kubicka, J. Wilkinson, D. Adair, J. Rakela, and T. Laskus. 2005. Persistence of hepatitis C virus in patients successfully treated for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 41:106-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roscic-Mrkic, B., R. A. Schwendener, B. Odermatt, A. Zuniga, J. Pavlovic, M. A. Billeter, and R. Cattaneo. 2001. Roles of macrophages in measles virus infection of genetically modified mice. J. Virol. 75:1345-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rouveix, B. 1992. Opiates and immune function. Consequences on infectious diseases with special reference to AIDS. Therapie 47:503-512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salmen, S., G. Teran, L. Borges, L. Goncalves, B. Albarran, H. Urdaneta, H. Montes, and L. Burrueta. 2004. Increased Fas-mediated apoptosis in polymorphonuclear cells from HIV-infected patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 137:166-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schaumann, R., J. Krosing, and P. M. Shah. 1998. Phagocytosis of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus by neutrophils of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 16:546-548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seddiki, N., A. Ben Younnes-Chennoufi, A. Benjouad, L. Saffar, N. Baumann, J. C. Gluckman, and L. Gattegno. 1996. Membrane glycolipids and human immunodeficiency virus infection of primary macrophages. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:695-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Serhan, C. N. 2004. A search for endogenous mechanisms of anti-inflammation uncovers novel chemical mediators: missing links to resolution. Histochem. Cell Biol. 122:305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shalekoff, S., C. T. Tiemessen, C. M. Gray, and D. J. Martin. 1998. Depressed phagocytosis and oxidative burst in polymorphonuclear leukocytes from individuals with pulmonary tuberculosis with or without human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:41-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smit-McBride, Z., J. J. Mattapallil, M. McChesney, D. Ferrick, and S. Dandekar. 1998. Gastrointestinal T lymphocytes retain high potential for cytokine responses but have severe CD4+ T-cell depletion at all stages of simian immunodeficiency virus infection compared to peripheral lymphocytes. J. Virol. 72:6646-6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sorensen, L. T., H. B. Nielsen, A. Kharazmi, and F. Gottrup. 2004. Effect of smoking and abstention on oxidative burst and reactivity of neutrophils and monocytes. Surgery 136:1047-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stefano, G. B., M. Salzet, C. M. Rialas, D. Mattocks, C. Fimiani, and T. V. Bilfinger. 1998. Macrophage behaviour associated with acute and chronic exposure to HIV GP120, morphine and anandamide: endothelial implications. Int J. Cardiol. 64(S1):3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Subramanyam, S., L. E. Hanna, P. Venkatesan, K. Sankaran, and P. R. Narayanan. 2004. HIV alters plasma and M. tuberculosis-induced cytokine production in patients with tuberculosis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 24:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suriki, H., K. Suzuki, Y. Baba, K. Hasegawa, R. Narisawa, Y. Okada, T. Mizuochi, H. Kawachi, F. Shimizu, and H. Asakura. 2000. Analysis of cytokine production in the colon of nude mice with experimental colitis induced by adoptive transfer of immunocompetent cells from mice infected with a murine retrovirus. Clin. Immunol. 97:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suzu, S., H. Harada, T. Matsumoto, and S. Okada. 2005. HIV-1 Nef interferes with M-CSF receptor signaling through Hck activation and inhibits M-CSF bioactivities. Blood 105:3230-3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tachavanich, K., K. Pattanapanyasat, S. Sarasombath, S. Suwannagool, and V. Suvattee. 1996. Opsonophagocytosis and intracellular killing activity of neutrophils in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 14:49-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tascini, C., F. Baldelli, C. Monari, C. Retini, D. Pietrella, D. Francisci, F. Bistoni, and A. Vecchiarelli. 1996. Inhibition of fungicidal activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from HIV-infected patients by interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10. AIDS 10:477-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Torre, D., A. Pugliese, G. Ferrario, G. Marietti, B. Forno, and C. Zeroli. 1994. Interaction of human plasma fibronectin with viral proteins of human immunodeficiency virus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 8:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Torre, D., L. Gennero, F. M. Baccino, F. Speranza, G. Biondi, and A. Pugliese. 2002. Impaired macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils in patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:983-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tremblay, M., M. Olivier, and R. Bernier. 1996. Leishmania and the pathogenesis of HIV infection. Parasitol. Today 12:257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trial, J., H. H. Birdsall, J. A. Hallum, M. L. Crane, Rodriguez-Barradas Mc, de A. L. Jong, B. Krishnan, C. E. Lacke, C. G. Figdor, and R. D. Rossen. 1995. Phenotypic and functional changes in peripheral blood monocytes during progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Effects of soluble immune complexes, cytokines, subcellular particulates from apoptotic cells, and HIV-1-encoded proteins on monocytes phagocytic function, oxidative burst, transendothelial migration, and cell surface phenotype. J. Clin. Investig. 95:1690-1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vecchiarelli, A., C. Monari, B. Palazzetti, F. Bistoni, and A. Casadevall. 2000. Dysregulation in IL-12 secretion by neutrophils from HIV-infected patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 121:311-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wilflingseder, D., Z. Banki, M. P. Dierich, and H. Stoiber. 2005. Mechanisms promoting dendritic cell-mediated transmission of HIV. Mol. Immunol. 42:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yoo, J., H. Chen, T. Kraus, D. Hirsch, S. Polyak, I. George, and K. Sperber. 1996. Altered cytokine production and accessory cell function after HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 157:1313-1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]