Abstract

Mountains, which constitute the majority of global biodiversity hotspots, are most vulnerable to ecosystem collapse due to various natural and anthropogenic stressors. Notably, over 90% of geopolitical conflicts have unfolded in the regions with global biodiversity hotspots. The Himalaya, Tibet and Hengduan (HTH) mountains are apt examples where climate change meets geopolitical conflict and militarization. Here, I advance a fresh proposal and hope that the neighbouring nations could bring to bear the neutrality of transboundary conservation areas, as part of their diplomatic tools, to broker a lasting peace. The proposal advocates establishing a Greater Himalayan Peace Reserve (GHPR) for posterity and regional ecological and economic security. The proposed reserve embraces the HTH mountains embodying some of the most biodiverse regions of the earth. These mountains also play a central role in controlling regional climate, water security and agricultural productivity of South and Southeast Asia. The GHPR is envisaged to be a potential regional platform for conservation diplomacy, and a model foundational framework for global sustainability and peace.

Subject terms: Environmental impact, Ecology, Evolution, Plant sciences, Climate sciences, Ecology

About four and a half years ago, a dream articulated on the pages of Nature proposed establishing the Himalayan highlands as a peace park1. The plea had a scientific basis: these areas comprise ‘centres of rich floral endemism and zones of active speciation’ where evolutionary biologists can actually observe ‘how species are born’. But the aspiration to conserve the ‘cradle of speciation’ was perhaps too inconsequential in the shadow of the border conflict that erupted in 2020 between India and China. Worryingly, these nurseries and epicentres of species richness continue to be amongst the most militarized zones. Given the discouraging background, the proposal to transform the mountains into ‘Himalaya one nature one reserve (HONOR)1,’ was an ‘idealistic aim.’ It conveyed that ‘alongside other multilateral strategies, the mountain range, or at least those areas between 2600 and 4600 m elevations - whose famous inhabitants include the snow leopard and its prey, the Himalayan blue sheep - should be designated as a nature reserve – spread over a 740,000 square kilometre area’1. The Worldview article attracted significant attention from fellow researchers and the press, but not from those who were in charge of decision-making.

Why is then a fresh and more elaborate conservation proposal being mooted here? The reasons behind this proposal will be discussed in more detail later, suffice it to say, because of the unique features of Himalaya (H), Tibet (T) and Hengduan (H), a contiguous group of mountains harbouring rich endemic floral diversity, and constituting major global biodiversity hotspots. Besides, these ecosystems harbour numerous unique niches, inhabited by diverse species with small population sizes. Even the slightest of stress, natural, anthropogenic or a combination of both, can push their unique endemic taxa to the brink of extinction2,3.

Thankfully, some months ago, India and China have decided to de-escalate and return to their pre 2020 positions on the border. Meanwhile, additional infrastructure in the form of roads and buildings constructed during the last four years has upended likely benefits of peace. Numerous Himalayan habitats stand fragmented, degraded and destroyed. Nevertheless, buoyed by the news of military disengagement, the dream to conserve and protect Himalaya4, as a peace reserve has grown firmer and more expansive - the HONOR must extend beyond the previously proposed boundaries1 to include the three contiguous mountains spread over ~3 million km2, designated here as the Greater Himalayan Peace Reserve (GHPR). Primarily, the reasons for establishing the peace reserve comprise a tapestry of objectives for interested and well-informed citizens, students, scholars and those who dare to dream of mountains as safe spaces against all odds. Importantly, the colloidal mountains such the HTH are characterised by intrinsic geological vulnerability and ecological fragility that demand some explaining to appreciate the need for their conservation.

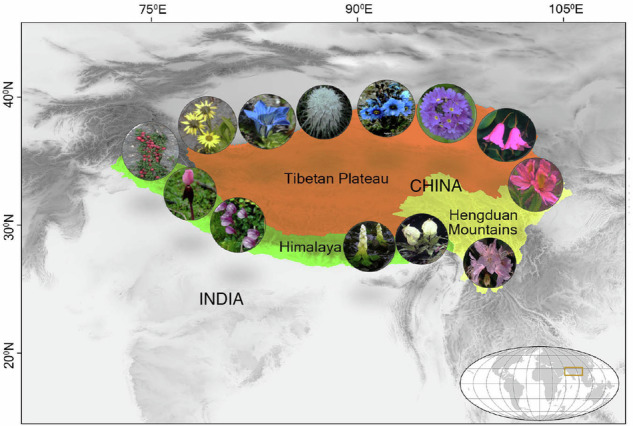

HTH - an exclusive home of the unique and endemic taxa such as the rhododendrons, the gentians, the saussureas, the poppies (Fig. 1) and unique habitats of flagship wildlife - the snow leopard and the blue sheep, deserve to be protected, for neither the habitats nor their biodiversity can be replicated elsewhere. The habitats of these unique species, whose lives predate ours by tens of millions of years, are shrinking fast owing to human pressure and on-going warming. The principle of natural justice demands that the right of these unique species inhabiting the mountains needs to be recognized and prioritized for conservation. Sadly, there is little space in the human mind for the rest of nature’s not-so-exalted creations. It is another matter that philosophies of the Eastern cultures, predominant in the region – Hindus and Buddhists – both tend to think of all life forms to be at the same pedestal – man or the marmot - doesn’t matter.

Fig. 1. The three contiguous mountain areas – the Himalaya, the Tibetan Plateau and the Hengduan (HTH) shown here constitute major global biodiversity hotspots.

These mountains are widely known for their rich floral diversity and high endemism. A representative sample of the endemic taxa spread across the HTH shown here include: starting from 90 clock position (clockwise) – Gaultheria, Aster, Gentiana, Saussurea, Meconopsis, Primula, Rhododendron (3 species), Saussurea obvallata, Rheum nobile, Pedicularis and Podophyllum – all HTH endemics.

Beyond the consequences of global warming and militarization, their ecological significance and conservation worthiness, the HTH mountain region is threatened by numerous stressors. These include road-building, mega-engineering structures, such as dams5,6, expanding agriculture and settlements and human population growth2. These anthropogenic pressures have resulted in ecosystem disruption and degradation and these threats alone make for a compelling argument for the region’s conservation. Even though the HTH region boasts a number of protected/conservation areas (PAs/CAs), the myriad stressors along with the fact that existing PA boundaries are rendered less effective due to the impact of global warming7, there are enough reasons and scope for the establishment of GHPR.

Arguably, the absence of peace is the principal hindrance to conservation. Defense preparedness is a costly proposition for any nation’s exchequer, but wars are detrimental to ecology and the environment beyond their borders. From damaging pristine biodiversity-rich ecosystems and diverse wildlife habitats to creating large-scale air, water and soil pollution, life-sustaining environmental resources are the first casualty in a military conflict. Globally, between 1950 and 2000, more than 90% of major conflicts have arisen in areas comprising biodiversity hotspots8 such as the Himalaya. The on-going Russia-Ukraine war is estimated to have caused environmental damages of over $56.4 billion9,10 including pollution of water bodies with fuel oil rendering river and spring waters unfit for drinking and toxic for aquatic life. China and India spend around US$ 200–300 billion and US$ 73 billion, respectively on their annual defence budgets11. India’s economic costs of military engagement with China in 2020 amounted to nearly US$ 2.8 billion on unplanned contingent expenditure to ramp its armoury and capital expenditure on civil infrastructure and equipment12. The border conflict cost India an additional financial burden of US$ 0.78 billion as capital expenditure on the reinforcement of border road infrastructure12. Notably, India’s annual defence expenditure corresponds to 3.65 times the amount the nation spent on a noble cause - a free ration scheme for about 740 million beneficiaries during Covid-19, and 4.68 times the current school and higher education budget combined (US$ 15.6 billion). Therefore, GHPR and conservation diplomacy make better economic sense for both nations by saving billions of dollars in a peaceful setting.

Supporting arguments for and the reasons to establish GHPR include: (i) the shared geo-climatic histories, topographic and landscape development progression of HTH mountains2,13,14, (ii) their rich biodiversity and its distribution is a collective outcome of the region’s geo-climatic imprints, (c) the physical contiguity of these mountains has led to mutual biotic enrichment and endemism14,15, (d) HTH represent vast biodiversity estate of interconnected habitats spread over ~3 million km2 embodying tropical to alpine ecosystems, (e) seen together, these mountains are an unparalleled repository of unique species, and (f) the myriad ecosystems across HTH represent second-to-none informational resource as a living, breathing laboratory for observing processes and patterns of speciation.

Hengduan mountains are an older sibling of the interconnected HTH chain. These mountains attained rich floral diversity and endemism (>50%) ahead of Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau13,15. Hengduan mountains are also the ancestral source of plant biodiversity of the Himalaya, as revealed by recent ancestral area reconstruction models16. But for the Hengduan mountains, Himalayan floral endemism (40% or more) may have been way less than observed today. A fascinating interplay of orogeny, and climate (monsoon and glacial-interglacial cycles), followed by serendipitous events and processes, engendered rich biodiversity in the HTH region2,3,13. A cautious conjecture might suggest that as time goes by and more speciation occurs in the younger Himalayan mountains, a reverse speciation pump will come into effect further enhancing the biotic wealth of these mountains. This enthraling learning alone offers abundant motivation to young scholars and citizens to explore the dynamics of geo-climatic interactions in shaping the HTH biodiversity and its considerable conservation worth.

Despite their unique geo-climatic histories14,15, HTH mountains in their varied and phased uplifts, depict a remarkable parallelism in terms of newly established bioclimatic gradients, floral immigrations, and biodiversity build-up2,15,16. After their initial colonization by immigrant taxa, processes of geographic isolation and vicariance helped generate high species endemism. Rhododendron is a classic example of immigrant diversification in the Sino-Himalaya with more than 400 endemic species alone in the Hengduan mountains.

Following the mid-Miocene push, the high HTH mountains, by intercepting moist winds from the South and the Southwest, engendered the phenomenon of Asian monsoon17, which not only brought about changes in moisture regime of air and soil, but its intensification became the principal driver of redistribution of soil geochemistry along mountain slopes3. The edaphic gradients thus generated enhanced habitat heterogeneity, which is known to promote biotic diversity18. Intensification of monsoon also brought about large-scale changes in the topography and landscape morphology of the mountains, in particular the Hengduan and the Eastern Himalaya3,14, and thus transformed multiple valleys provided ample opportunities for geographic isolation of populations and diversification via vicariance3,13. Other major climatic upheaval of glaciation-interglaciation cycles during Pleistocene brought about population mixing and disjunctions, hybridization and polyploidy resulting in species radiations2,3 and their geographic redistribution. Plant migrations and exchanges, between HTH, followed by higher speciation rates during and post-Miocene epoch, accelerated floral endemism in the region. Each of these sub-regions acted as a ‘speciation pump’ - propelling a collective endemism surge in HTH mountains2,3,13,16.

Because of their unique bio-geo histories and potential to inspire a wide range of citizens across HTH nations including the riparian states in South and Southeast Asia, the GHPR proposal needs careful consideration by those who are vested with the political, diplomatic and administrative authority. We may think of the ~2.0 billion population of South and South-east Asia whose survival, in terms of water availability and agricultural productivity, depends on the rivers originating in the HTH region. This large mass of people must rally around the idea of building a broad coalition in support of conservation of the ‘biotic, water and food security tower’ of Asia. The effort will be the most befitting gift to the global conservation movement and regional sustainability.

The extended dream presented here is about the world’s youngest and tallest mountain chain, with the richest endemic biodiversity and vast ice fields, second only to the earth’s polar regions. This region needs to be secured from future geopolitical conflicts; conservation for the benefit of vast humanity and other life forms will be a worthy rallying point for peace. Despite the conflict, scientific and conservation cooperation between India and China must continue, as it has post-2020 in the field of trade. The security and diplomatic architecture of the Himalayan nations will find their stake in GHPR to be a noble and worthy cause for peaceful co-existence. Moreover, if the enormous financial resources are repurposed from the respective defense budgets and diverted to education, research and upskilling of young people, the conservation cause will gain more legitimacy and acceptability. There cannot be a better and bigger sustainable development goal for the globe to achieve than to usher peace and sustainability mediated by conservation. We cannot undermine the fact that India and China comprise nearly one-third of the global human population and their meeting of minds and cooperation holds the key to global peace and sustainability19.

Acknowledgements

I thank Peter Pang of the National University of Singapore for the institutional affiliation, and the award of Ngee Ann Kongsi Distinguished Visiting Professorship. I also thank Kumar Manish, Jindal School of Environment & Sustainability. The insightful comments of anonymous reviewers and editors are gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

M.K.P. conceptualised, designed, and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pandit, M. K. The Himalaya should be a nature reserve. Nature583, 9–9 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandit, M. K. et al. Dancing on the roof of the world: ecological transformation of the Himalayan landscape. BioScience64, 980–992 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandit, M. K. Life in the Himalaya: an ecosystem at risk. (Harvard University Press, 2017).

- 4.Pandit, M. K. The Himalayas must be protected. Nature501, 283–283 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandit, M. K. & Grumbine, R. E. Potential effects of ongoing and proposed hydropower development on terrestrial biological diversity in the Indian Himalaya. Conserv. Biol.26, 1061–1071 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grumbine, R. E. & Pandit, M. K. Threats from India’s Himalaya dams. Science339, 36–37 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manish, K. & Pandit, M. K. Identifying conservation priorities for plant species in the Himalaya in current and future climates: A case study from Sikkim Himalaya, India. Biol. Conserv.233, 176–184 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson, T. et al. Warfare in biodiversity hotspots. Conserv. Biol.23, 578–587 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hryhorczuk, D. et al. The environmental health impacts of Russia’s war on Ukraine. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol.19, 1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira, P. et al. Russian-Ukrainian war impacts the total environment. Sci. Total Environ.837, 155865 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ET Online. India vs China: A tale of two defence budgets. The Economic Times. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-vs-china-a-tale-of-two-defence-budgets/articleshow/98498491.cms (2023).

- 12.Kaushik, K. India to keep spending on border roads after 30% budget overrun on China fears. Reuters. February 1, 2024. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-keep-spending-border-roads-after-30-budget-overrun-china-fears-2024-02-01/.

- 13.Ding, W. N., Ree, R. H., Spicer, R. A. & Xing, Y. W. Ancient orogenic and monsoon-driven assembly of the world’s richest temperate alpine flora. Science369, 578–581 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manish, K. & Pandit, M. K. Geophysical upheavals and evolutionary diversification of plant species in the Himalaya. PeerJ6, e5919 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spicer, R. A. Tibet, the Himalaya, Asian monsoons and biodiversity–In what ways are they related? Plant Divers39, 233–244 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manish, K., Pandit, M. K. & Sen, S. Inferring the factors for origin and diversifications of endemic Himalayan flora using phylogenetic models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ.8, 2591–2598 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clift, P. D. et al. Correlation of Himalayan exhumation rates and Asian monsoon intensity. Nat. Geosci.1, 875–880 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonelli, A. et al. Geological and climatic influences on mountain biodiversity. Nat. Geosci11, 718–725 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bawa, K. S. et al. China and India: Toward a sustainable world. Science369, 515–515 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.