Abstract

Despite long-term survival reports in early gastric cancer, comparative life expectancy data with the general population is scarce. This study aimed to estimate patients’ life expectancy and analyze disparities between early gastric cancer patients and the general population. Patients with stage 1 gastric cancer who underwent curative gastrectomy at Asan Medical Center were enrolled. Survival status was tracked via national health insurance records. Life expectancy was compared with general population data from the Korean Statistical Information Service database. The cohort comprised 8,637 patients (64.7% men, 17.3% aged 70+). Approximately 20% of patients underwent total gastrectomy. Life expectancy was favorable among women. Across all age groups, women’s life expectancy generally exceeded 80 years. Male patients showed a reduced life expectancy, typically 4–10 years shorter than their female counterparts. The average life expectancy of male patients aged over 80 years who underwent total gastrectomy was about 5 years, whereas that of their female counterparts was approximately 7 years. Female patients undergoing distal gastrectomy did not demonstrate a statistically significant variance in life expectancy compared to the general population. This study provided comprehensive life expectancy data, organized by age, sex, and type of gastrectomy in a large stage 1 gastric cancer cohort. Our findings are expected to alleviate uncertainties and anxieties for individuals diagnosed with early gastric cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-89158-y.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Life expectancy, Gastrectomy, Survival

Subject terms: Gastrointestinal cancer, Cancer

Introduction

The proportion of early gastric cancer increased from 33.1% in the period from 1986 to 1990 to 60.9% in the period from 2001 to 2006, according to a study that analyzed the clinical and pathological characteristics of gastric cancer over a 20-year period1. This trend aligns with the results of the 2019 National Survey of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association, which reported that the incidence of early gastric cancer has been increasing gradually, reaching 28.6% in 1995 and 63.6% in 20192. Furthermore, it is estimated that the rate of early gastric cancer is even higher in patients who underwent endoscopic treatment.

The survival rate of patients with gastric cancer has also undergone gradual improvement, with the 5-year survival rate approximating 73.2%. The survival rate for stage 1 gastric cancer is notably better, with reported 5-year survival rates of about 94.4% for stage IA and 84.2% for stage IB1. This improvement is attributed to various factors, including the implementation of national cancer screening programs, which have increased the rate of early diagnosis, advancements in laparoscopic surgery, and the utilization of endoscopic procedures3–8.

However, few studies have provided data on the survival rates of gastric cancer, and information on the extent to which these patients will survive in the future is quite limited. According to a Taiwanese study investigating the life expectancy of patients with gastric cancer, male sex and gastric cancer arising from the cardia were associated with a shorter life expectancy9. However, that study did not provide information distinguishing the life expectancy between early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer, nor did it compare the results to the general population. Furthermore, there is currently a lack of studies specifically examining life expectancy in Korean patients with gastric cancer. Accurate information on life expectancy can greatly aid patients in alleviating vague anxiety associated with a cancer diagnosis. It enables them to make more specific plans for their lives and families, by accounting for the potential time frame and prognosis.

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the disparity in life expectancy between patients with early gastric cancer and the general population. Additionally, it examined the life expectancy of patients with early gastric cancer based on age and sex.

Methods

Patients

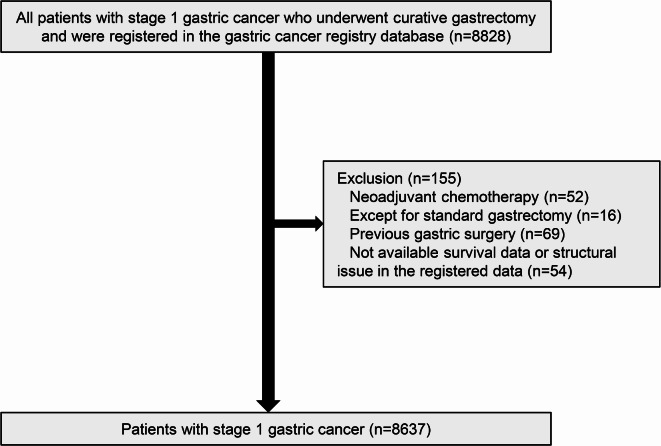

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center, we enrolled patients from the gastric cancer registry of this institution for this study (2022 − 1741). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center, approved a waiver of informed consent for all subjects, as this study utilized only the institution’s gastric cancer registry and publicly available data. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the committee. We focused on 8,828 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy and were diagnosed with pathologic stage 1 gastric cancer between March 2005 and December 2019. We excluded patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n = 52), those with a history of gastric surgery (n = 69), those who underwent surgeries other than standard gastrectomy (n = 16), and those with structural issues in the registered data (n = 54). Consequently, our study analyzed a cohort of 8,637 patients. Figure 1 presents detailed information on the patient enrollment process.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of this study.

Clinical, pathological, and surgical information

The patients’ clinicopathological and surgery-related information was collected. This study included data such as age, sex, height, weight, family history of gastric cancer, history of abdominal surgery, comorbidities, date and time of operation, type of surgical approach, extent of gastrectomy, type of anastomosis, extent of lymphadenectomy, tumor size, histology, depth of tumor, number of metastatic lymph nodes, tumor stage, nodal stage, TNM stage10, presence of distant metastasis, and chemotherapy.

Statistical analysis of survival probabilities and life expectancy

The participants’ survival status was determined using the national health insurance system. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparison between groups. The participants’ life expectancy was analyzed and compared to the that of the general population based on data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) database using the following methods. The period life tables. The period life tables used to calculate life expectancy were constructed from number of deaths and person-years at each age interval. The first two values of person-years lived by those dying in the first two intervals was handled using Keyfitz and Fleiger’s (1990)11 regression method to calculate life expectancy. The 95% confidence intervals of life expectancy were calculated using the bootstrap method. The comparison with life expectancy of the general population at 2021 years was analyzed using 1000 bootstrap resampling. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.6.1 packages “survival” and “demogR”. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the entire study cohort. Approximately 5.5% of participants were under 40 years old, whereas those aged 70 years and older constituted 17.9% of the population. Men accounted for 64.7% of the total population, and 44.0% of patients had at least one comorbidity. Roughly 20% of patients underwent total gastrectomy. Billroth I was the most common reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy, accounting for 42.2% of cases. D1 + dissection was performed in 25.8% of cases. Poorly differentiated or signet ring cell type tumors accounted for 53.4%, whereas intestinal tumors accounted for 46.5% of lesions. The majority of tumors were classified as T1 (90.8%), and 5.77% tumors were N1. Stage IA and Stage IB accounted for 85.15% and 14.85% of lesions, respectively. At the end of the follow-up period, 84.0% of patients were still alive.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Variables | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| < 40 | 470 | 5.44 |

| 40–49 | 1600 | 18.52 |

| 50–59 | 2641 | 30.58 |

| 60–69 | 2377 | 27.52 |

| ≥ 70 | 1549 | 17.93 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 35 | 0.41 |

| 30–39 | 435 | 5.04 |

| 40–49 | 1600 | 18.52 |

| 50–59 | 2641 | 30.58 |

| 60–69 | 2377 | 27.52 |

| 70–79 | 1357 | 15.71 |

| 80+ | 192 | 2.22 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5584 | 64.65 |

| Female | 3053 | 35.35 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | ||

| < 18.5 | 228 | 2.71 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 5176 | 61.59 |

| ≥ 25.0 | 3000 | 35.7 |

| Status at the end of follow-up | ||

| Alive | 7253 | 83.98 |

| Dead | 1384 | 16.02 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| No | 4834 | 55.97 |

| Yes | 3803 | 44.03 |

| Extent of gastrectomy | ||

| Distal | 6880 | 79.66 |

| Total | 1757 | 20.34 |

| Type of anastomosis | ||

| B-I (Extracorporeal) | 3641 | 42.16 |

| Delta (Intracorporeal) | 1862 | 21.56 |

| B-II | 630 | 7.29 |

| RYGJ | 747 | 8.65 |

| RYEJ | 1757 | 20.34 |

| LN dissection | ||

| D1 (including less than D1) | 416 | 4.82 |

| D1+ | 2214 | 25.69 |

| D2 | 5859 | 67.99 |

| D3 | 129 | 1.5 |

| Histology | ||

| WD/MD | 3656 | 42.44 |

| PD/SRC | 4598 | 53.38 |

| Papillary | 61 | 0.71 |

| Mucinous | 75 | 0.87 |

| Others | 224 | 2.6 |

| Lauren | ||

| Intestinal | 3967 | 46.54 |

| Diffuse | 3279 | 38.47 |

| Mixed | 1218 | 14.29 |

| Indeterminate | 60 | 0.7 |

| T stage | ||

| T1 | 7844 | 90.82 |

| T2 | 793 | 9.18 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 8134 | 94.18 |

| N1 | 503 | 5.82 |

| TNM stage | ||

| Stage IA | 7354 | 85.15 |

| Stage IB | 1283 | 14.85 |

BMI = body mass index; RYGJ = Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy; RYEJ = Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy LN = lymph node; WD = well differentiated adenocarcinoma; MD = moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; SRC = signet ring cell carcinoma; PD = poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma;

Supplemental Table 1 presents the 5-, 10-, and 15-year overall survival rates for the entire cohort as well as a sex-based breakdown. The overall survival rates of the whole cohort at 5, 10, and 15 years were 95.0%, 87.5%, and 77.4%, respectively. Notably, male patients exhibit lower survival rates compared to their female counterparts, with a discrepancy of approximately 4.1% at 5 years, 9.7% at 10 years, and 15.3% at 15 years. This contrast became more pronounced with the passage of time. Figure 2 depicts the analysis of the mortality curve. Supplemental Table 2 illustrates the survival rates by age group. As per the data presented, it is evident that the survival rate underwent a more pronounced decline, starting at the age of 70 years. This trend was especially prominent among male patients, whereas the survival rates remain relatively stable among female patients.

Fig. 2.

Mortality curve by sex group.

Table 2 demonstrates the survival probabilities categorized by age, sex, and the extent of gastrectomy. The findings reveal that among individuals aged 70 years and older, men had poorer survival rates compared to women, particularly male patients who underwent total gastrectomy, whose survival outcomes were notably lower.

Table 2.

Survival probabilities (%) by age, sex, and extent of gastrectomy.

| Variable | Men (n = 5584) | Women (n = 3053) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Distal gastrectomy | Total gastrectomy | Total | Distal gastrectomy | Total gastrectomy | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | N | 5-year survival probability (%) | 10-year survival probability (%) | 15-year survival probability (%) | |

| 20–29 | 16 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 15 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 1 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 19 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 15 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 4 | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) |

| 30–39 | 204 | 99.51 (96.57, 99.93) | 97.94 (94.59, 99.22) | 95.36 (88.7, 98.13) | 161 | 99.38 (95.67, 99.91) | 98.04 (94.02, 99.36) | 94.84 (86.51, 98.08) | 43 | 100 (100, 100) | 97.67 (84.62, 99.67) | 97.67 (84.62, 99.67) | 231 | 99.13 (96.58, 99.78) | 98.58 (95.64, 99.54) | 97.7 (93.7, 99.17) | 181 | 99.45 (96.14, 99.92) | 99.45 (96.14, 99.92) | 98.28 (92.69, 99.6) | 50 | 98 (86.64, 99.72) | 95.49 (82.97, 98.86) | 95.49 (82.97, 98.86) |

| 40–49 | 906 | 98.01 (96.86, 98.74) | 95.23 (93.57, 96.47) | 91.78 (89.27, 93.72) | 719 | 98.33 (97.08, 99.05) | 95.73 (93.91, 97.02) | 92.94 (90.32, 94.87) | 187 | 96.79 (92.99, 98.54) | 93.32 (88.51, 96.15) | 86.77 (78.31, 92.09) | 694 | 98.99 (97.89, 99.52) | 97.91 (96.49, 98.76) | 95.04 (92.02, 96.94) | 564 | 99.11 (97.88, 99.63) | 97.96 (96.35, 98.87) | 95.08 (91.45, 97.19) | 130 | 98.46 (93.99, 99.61) | 97.69 (93, 99.25) | 94.79 (87.39, 97.9) |

| 50–59 | 1740 | 96.72 (95.77, 97.46) | 92.01 (90.58, 93.23) | 85.84 (83.19, 88.09) | 1385 | 96.97 (95.92, 97.75) | 92.6 (91.03, 93.9) | 86.44 (83.35, 88.99) | 355 | 95.77 (93.09, 97.43) | 89.63 (85.76, 92.5) | 83.31 (77.43, 87.78) | 901 | 99 (98.09, 99.48) | 96.33 (94.81, 97.41) | 94.15 (91.77, 95.86) | 706 | 99.01 (97.93, 99.53) | 96.37 (94.62, 97.56) | 94.1 (91.25, 96.04) | 195 | 98.97 (95.96, 99.74) | 96.15 (92.08, 98.15) | 94.37 (89.21, 97.1) |

| 60–69 | 1670 | 93.34 (92.04, 94.44) | 84.11 (82.19, 85.83) | 67.15 (63.56, 70.48) | 1281 | 93.51 (92.02, 94.73) | 84.81 (82.66, 86.72) | 68.15 (64.13, 71.82) | 389 | 92.78 (89.71, 94.96) | 81.65 (77.14, 85.35) | 63.74 (55.37, 70.96) | 707 | 96.88 (95.31, 97.94) | 92.83 (90.59, 94.55) | 85.84 (80.38, 89.87) | 585 | 97.26 (95.57, 98.31) | 93.12 (90.66, 94.95) | 85.7 (79, 90.39) | 122 | 95.08 (89.38, 97.76) | 91.48 (84.71, 95.33) | 85.63 (74.9, 92.01) |

| 70–79 | 920 | 85.09 (82.62, 87.24) | 58.35 (54.89, 61.64) | 33.36 (27.48, 39.33) | 717 | 87.02 (84.33, 89.27) | 61.33 (57.44, 64.98) | 33.65 (27.05, 40.37) | 203 | 78.25 (71.9, 83.33) | 47.69 (40.16, 54.82) | 35.21 (23.53, 47.09) | 437 | 94.73 (92.18, 96.47) | 82.27 (78.16, 85.68) | 60.5 (51.57, 68.29) | 375 | 95.46 (92.8, 97.16) | 82.94 (78.55, 86.51) | 61.36 (51.5, 69.81) | 62 | 90.32 (79.72, 95.53) | 77.25 (62.79, 86.66) | 52.23 (27.81, 71.92) |

| 80+ | 128 | 64.61 (55.44, 72.36) | 34.64 (24.52, 44.96) | 7.56 (0.79, 25.22) | 115 | 66.96 (57.34, 74.88) | 37.9 (26.95, 48.77) | 8.27 (0.84, 27.24) | 13 | 46.15 (19.16, 69.64) | 27.69 (7.13, 53.56) | 27.69 (7.13, 53.56) | 64 | 78.64 (65.93, 87.06) | 61.25 (42.94, 75.26) | 53.59 (32.1, 71.01) | 61 | 79.28 (66.27, 87.73) | 65.91 (48.25, 78.78) | 57.67 (35.33, 74.73) | 3 | 66.67 (5.41, 94.52) | 66.67 (5.41, 94.52) | 66.67 (5.41, 94.52) |

In addition, we analyzed the life expectancy among all patients who underwent curative gastrectomy for early gastric cancer within this cohort, classifying them by age, sex, and extent of gastrectomy (Table 3). In general, our findings demonstrated a significantly favorable life expectancy among female patients. Across all age groups, we anticipated a life expectancy exceeding 80 years in female patients. In contrast, male patients exhibited a life expectancy that was approximately 4 to 10 years less than that of their female counterparts. Among men, the divergence in life expectancy between those undergoing distal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy ranged from 2 to 4 years, whose magnitude was less than that observed difference in women (approximately 4 to 7 years). Among male patients aged 80 years and above who underwent total gastrectomy, the observed life expectancy was approximately 5 years, whereas their female counterparts demonstrated a life expectancy of approximately 7 years.

Table 3.

Life expectancy stratified by age, sex, and extent of gastrectomy.

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Distal gastrectomy | Total gastrectomy | Total | Distal gastrectomy | Total gastrectomy | |

| 20–29 | 54.33 | 54.83 | 52.21 | 63.81 | 64.56 | 57.93 |

| 30–34 | 44.33 | 44.83 | 42.21 | 53.81 | 54.56 | 47.93 |

| 35–39 | 40.27 | 40.98 | 37.21 | 49.42 | 49.95 | 44.28 |

| 40–44 | 35.73 | 36.43 | 32.69 | 44.68 | 45.12 | 39.79 |

| 45–49 | 31.52 | 32.2 | 28.52 | 40.25 | 40.68 | 35.32 |

| 50–54 | 27.39 | 27.95 | 24.78 | 35.78 | 36.17 | 30.96 |

| 55–59 | 23.36 | 23.95 | 20.59 | 31.47 | 31.92 | 26.4 |

| 60–64 | 19.48 | 19.96 | 17.03 | 27.07 | 27.44 | 22.22 |

| 65–69 | 15.9 | 16.38 | 13.32 | 22.7 | 22.92 | 18.35 |

| 70–74 | 12.86 | 13.36 | 10.05 | 18.86 | 19.08 | 14.29 |

| 75–79 | 10.56 | 10.99 | 7.6 | 15.42 | 15.53 | 11.05 |

| 80–84 | 8.92 | 9.33 | 5.35 | 13.05 | 13.24 | 7.44 |

| 85+ | 7.73 | 8.04 | 3.67 | 10.38 | 10.38 | |

Finally, we conducted a comparative analysis to assess the statistical disparities in life expectancy between our cohort and the general population using data from the KOSIS database, stratified by sex and surgical procedure (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 1). Compared to the general population, all male patients demonstrated a difference in life expectancy ranging from approximately 0.42 years to 6 years across the different age groups. Notably, female patients undergoing distal gastrectomy did not demonstrate a statistically significant variance in life expectancy compared to the general population. Moreover, patients aged 75 years and above who underwent distal gastrectomy exhibited a superior life expectancy compared to the general population. In contrast, female patients undergoing total gastrectomy displayed a life expectancy difference of 4–10 years compared to the general population, albeit without any statistical significance.

Table 4.

Life expectancy of patients with early gastric cancer compared to the general population.

| Total | Distal gastrectomy | Total gastrectomy | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in LE | LE | 95% CI | p value | Difference in LE | LE | 95% CI | p value | Difference in LE | LE | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Men | ||||||||||||||

| 20–29 | 1.77 | 54.33 | 52.77–55.92 | 0.032 | 1.27 | 54.83 | 53.06–56.78 | 0.192 | 3.53 | 52.57 | 50.65–54.67 | 0.004 | ||

| 30–34 | 6.97 | 44.33 | 42.79–45.92 | 0.002 | 6.47 | 44.83 | 43.06–46.78 | 0.002 | 8.73 | 42.57 | 40.65–44.67 | 0.002 | ||

| 35–39 | 6.23 | 40.27 | 39.21–41.70 | 0.002 | 5.52 | 40.98 | 39.69–42.81 | 0.002 | 8.93 | 37.57 | 35.65–39.67 | 0.002 | ||

| 40–44 | 5.97 | 35.73 | 34.76–37.07 | 0.002 | 5.27 | 36.43 | 35.35–38.16 | 0.002 | 8.65 | 33.05 | 31.47–35.04 | 0.002 | ||

| 45–49 | 5.38 | 31.52 | 30.54–32.92 | 0.002 | 4.70 | 32.2 | 31.12–33.93 | 0.002 | 8.01 | 28.89 | 27.53–30.76 | 0.002 | ||

| 50–54 | 4.91 | 27.39 | 26.46–28.89 | 0.002 | 4.35 | 27.95 | 26.86–29.66 | 0.002 | 7.13 | 25.17 | 23.91–27.12 | 0.002 | ||

| 55–59 | 4.44 | 23.36 | 22.42–24.86 | 0.002 | 3.85 | 23.95 | 22.84–25.76 | 0.004 | 6.81 | 20.99 | 19.75–22.85 | 0.002 | ||

| 60–64 | 4.02 | 19.48 | 18.52–21.01 | 0.002 | 3.54 | 19.96 | 18.86–21.75 | 0.004 | 6.03 | 17.47 | 16.21–19.46 | 0.002 | ||

| 65–69 | 3.40 | 15.9 | 14.84–17.52 | 0.004 | 2.92 | 16.38 | 15.22–18.25 | 0.012 | 5.51 | 13.79 | 12.45–15.81 | 0.002 | ||

| 70–74 | 2.54 | 12.86 | 11.67–14.66 | 0.018 | 2.04 | 13.36 | 12.04–15.47 | 0.062 | 4.80 | 10.6 | 9.19–12.95 | 0.004 | ||

| 75–79 | 1.14 | 10.56 | 9.11–12.87 | 0.232 | 0.71 | 10.99 | 9.42–13.56 | 0.482 | 3.36 | 8.34 | 6.57–11.36 | 0.038 | ||

| 80–84 | − 0.42 | 8.92 | 6.98–12.25 | 0.745 | − 0.83 | 9.33 | 7.24–12.88 | 0.523 | 2.01 | 6.49 | 4.05–10.96 | 0.266 | ||

| 85 + | − 1.73 | 7.73 | 4.81–12.94 | 0.302 | − 2.04 | 8.04 | 4.89–13.41 | 0.252 | ||||||

| Women | ||||||||||||||

| 20–29 | − 1.81 | 63.81 | 60.08–78.87 | 0.450 | − 2.56 | 64.56 | 60.67–80.06 | 0.272 | 4.07 | 57.93 | 52.98–70.89 | 0.248 | ||

| 30–34 | 3.29 | 53.81 | 50.08–68.87 | 0.517 | 2.54 | 54.56 | 50.67–70.06 | 0.613 | 9.17 | 47.93 | 42.98–60.89 | 0.074 | ||

| 35–39 | 2.88 | 49.42 | 45.63–64.41 | 0.563 | 2.35 | 49.95 | 46.03–65.41 | 0.631 | 8.02 | 44.28 | 40.25–57.78 | 0.080 | ||

| 40–44 | 2.72 | 44.68 | 40.89–59.89 | 0.581 | 2.28 | 45.12 | 41.22–60.96 | 0.643 | 7.61 | 39.79 | 35.82–53.85 | 0.086 | ||

| 45–49 | 2.35 | 40.25 | 36.41–55.36 | 0.625 | 1.92 | 40.68 | 36.80–56.48 | 0.687 | 7.28 | 35.32 | 31.39–49.94 | 0.094 | ||

| 50–54 | 2.02 | 35.78 | 31.89–51.13 | 0.671 | 1.63 | 36.17 | 32.17–52.32 | 0.725 | 6.84 | 30.96 | 26.92–45.91 | 0.112 | ||

| 55–59 | 1.63 | 31.47 | 27.52–46.99 | 0.729 | 1.18 | 31.92 | 27.84–48.32 | 0.799 | 6.70 | 26.4 | 22.34–41.40 | 0.126 | ||

| 60–64 | 1.33 | 27.07 | 23.02–42.82 | 0.775 | 0.96 | 27.44 | 23.29–44.30 | 0.831 | 6.18 | 22.22 | 18.06–37.21 | 0.148 | ||

| 65–69 | 1.00 | 22.7 | 18.61–38.98 | 0.827 | 0.78 | 22.92 | 18.69–40.22 | 0.865 | 5.35 | 18.35 | 14.09–34.21 | 0.174 | ||

| 70–74 | 0.34 | 18.86 | 14.51–35.97 | 0.965 | 0.12 | 19.08 | 14.66–36.97 | 0.995 | 4.91 | 14.29 | 9.90–31.20 | 0.210 | ||

| 75–79 | − 0.52 | 15.42 | 10.69–34.45 | 0.879 | − 0.63 | 15.53 | 10.71–34.94 | 0.859 | 3.85 | 11.05 | 5.96–31.31 | 0.334 | ||

| 80–84 | − 2.05 | 13.05 | 7.37–35.84 | 0.591 | − .2.24 | 13.24 | 7.49–36.55 | 0.549 | 3.56 | 7.44 | 1.8–17.1 | 0.330 | ||

| 85 + | − 2.68 | 10.38 | 3.49–37.46 | 0.587 | − 2.68 | 10.38 | 3.49–37.46 | 0.587 | ||||||

LE Life Expectancy.

A reduction in life expectancy of approximately 2–3 years was observed in male patients aged 75 years and above who underwent total gastrectomy compared to the general population. Similarly, in female patients, there was a decrease in life expectancy of approximately 3–4 years among those who underwent total gastrectomy compared to the general population.

Discussion

This study holds significant value by virtue of being the first analysis of life expectancy in patients with early-stage gastric cancer. Particularly noteworthy is the comparison with the general population, which allowed us to discern the extent of differences in life expectancy among patients across different age groups, sexes, and surgical procedures. This information is crucial to facilitate practical application in clinical settings, especially in guiding treatment decision-making for patients with early gastric cancer.

The strengths of our study lie in its incorporation of a substantial cohort of stage 1 gastric cancer patients, even though it was conducted at a single institution. This allowed us to conduct insightful subgroup analyses based on age, sex, and surgical approach. Furthermore, we had the privilege of tracking the long-term survival of patients in our cohort for an average duration exceeding 10 years, whereas drawing upon reliable data from the national health insurance service.

Another notable aspect of this study is its ability to project the life expectancy of patients with early-stage gastric cancer. Based on these findings, we were able to ascertain the disparity in life expectancy between patients with early gastric cancer and the general population. A nationwide retrospective cohort study conducted by Chen et al. in Taiwan stands as the sole research endeavor in the country to estimate the life expectancy of patients with gastric cancer9. However, the limitation of that study is that it encompassed the entire gastric cancer population without considering detailed staging information, engendering challenges for practical clinical implementation. In contrast, our study successfully surmounted this limitation by specifically targeting patients with stage 1 gastric cancer, a subgroup known for relatively high survival rates. Through a comprehensive analysis that accounted for age, sex, and surgical approach, our research evolved into a valuable resource, with potential applicability in clinical practice.

Additional significant feature of this study lies in its extensive long-term follow-up of patients with early-stage gastric cancer, averaging more than 10 years. Historically, long-term studies on gastric cancer have primarily centered on examining remnant stomach cancer incidence, typically entailing a median follow-up period up to 12.5 years12,13. However, these studies often fell short in providing comprehensive data on overall survival. The majority of studies investigating the survival rate focused on the treatment outcomes of early gastric cancer, predominantly reporting 5-year survival rates6,14. In contrast, the results presented in this study that encompassed an average follow-up period exceeding 10 years introduce substantial value to the existing body of literature.

The clinical implications of this research for the treatment of patients with early gastric cancer are as follows. First, there were considerable differences in the survival rates and life expectancy between men and women. Male patients exhibited lower survival rates and life expectancy compared to their female counterparts. However, the life expectancy exceeded 80 years even in young women with early-onset gastric cancer. These disparities may be attributed to a potential hypothesis suggesting that men exhibit a higher comorbidity rate and more risk factors for gastric cancer than women15,16. Consequently, our research results are consistent with those of existing studies, affirming that the overall survival tends to be less favorable for men than for women17,18. Furthermore, the incidence of remnant gastric cancer and the associated risk of Helicobacter pylori infection, which can contribute to it, are higher in men12,13,19–21. Additionally, there is a possibility that compliance with screening for recurrence after surgery is lower in men than in women, underscoring the importance of postoperative screening22.

The second finding suggests that the difference in life expectancy between total gastrectomy and distal gastrectomy is more pronounced in female patients than that in male patients. Li et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 11 studies and analyzed the stage specific survival, concluding that the overall survival of patients undergoing total gastrectomy is comparable to that of those undergoing distal gastrectomy23. These findings were based on survival curves analyzing the entire patient population, including all age groups. In contrast to these survival curve results, our study focused on analyzing life expectancy by age group. In female patients, total gastrectomy resulted in a greater reduction in life expectancy compared to distal gastrectomy. The hypothesis is that female patients who undergo total gastrectomy may be more nutritionally vulnerable than men. Tanabe et al. conducted a multicenter study of over 1700 patients who underwent gastric cancer surgery to investigate weight loss and predictive factors. They performed multiple regression analysis and found that factors such as higher preoperative BMI, total gastrectomy, and female sex were factors that influenced postoperative weight loss24. Given that significant postoperative weight loss can negatively impact long-term survival, it is likely that these results indicate the vulnerability of female patients, especially those who undergo total gastrectomy. However, the limited information on the nutritional status of patients who underwent distal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy in this study restricts the depth of analysis in this regard.

Whether long-term follow-up is warranted for female patients undergoing total gastrectomy, particularly to assess the need for specific nutritional interventions based on nutritional data, remains an area for future research.

Third, in the context of life expectancy, a notable observation was that distal gastrectomy has a modest effect on the lifespan of patients with early gastric cancer. Previous large-scale randomized controlled trials have indicated a 5-year survival rate exceeding 93% in patients with early gastric cancer undergoing distal gastrectomy, suggesting a favorable survival outcome6,14. However, the question of the actual duration of these patients’ survival remained unanswered. This study contributes valuable insights to this inquiry, elucidating that distal gastrectomy does not exhibit a substantial variance in life expectancy compared to the general population. Moreover, female patients and those aged 75 years or above demonstrated even better life expectancy outcomes upon undergoing distal gastrectomy than the general population.

Finally, special consideration is warranted when performing total gastrectomy for patients aged 80 years and above, as their life expectancy after gastrectomy is notably limited to approximately 7 years. Compared to the life expectancy outcomes reported by Schoenborn et al. in 2022, the life expectancy of patients over 80 who received distal gastrectomy in the current study is comparable to those with no comorbidities and the low frailty group. However, the life expectancy of patients aged above 80 years who underwent total gastrectomy is not as favorable, aligning with the high comorbidities group in the previous study25. Furthermore, a study utilizing data from over 100,000 individuals conducted by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association suggested that elderly patients undergoing surgery for early gastric cancer have a higher likelihood of dying from causes other than gastric cancer during long-term follow-up. Therefore, they proposed considering the balance between the invasiveness of treatment and prognosis during treatment decision-making26. Additionally, Endo et al. conducted a retrospective review of gastric cancer surgery patients aged 80 years and above and found that those undergoing total gastrectomy had significantly worse gastric cancer-specific survival time compared to those undergoing distal gastrectomy. Especially, cases of mortality due to pneumonia were more prevalent27. Therefore, in terms of the patient’s prognosis, if tumor size and location permit, it would be advisable to opt for stomach preserving gastrectomy including local resection, proximal gastrectomy, and other suitable techniques in cases of early upper gastric cancer.

In this study, when interpreting life expectancy outcomes based on the type of gastrectomy, several factors need to be considered. First, since both groups include patients with early gastric cancer, the risk of recurrence is extremely low. Therefore, oncologic outcomes are unlikely to have a significant impact on survival. Another crucial factor is the effect of postoperative complications. Previous studies have consistently reported higher overall complication rates following total gastrectomy compared to distal gastrectomy23,28, with anastomotic leakage and intra-abdominal abscess being particularly more frequent. Such complications often lead to prolonged fasting and extended hospital stays, contributing to poor nutritional status and a weakened overall condition. This, in turn, increases the risk of systemic illnesses. These interconnected factors may collectively influence long-term prognosis, including life expectancy. Moreover, in patients with comorbidities, such detrimental interactions may be further amplified29. However, this study does not provide detailed information on the type and severity of complications and comorbidities, which could have offered deeper insights into their impact.

This study has several limitations. First, as mentioned earlier, since this study is a retrospective analysis conducted at a single institution, it lacks comprehensive data on factors that could influence life expectancy, such as patients’ performance status, nutritional status, and postoperative complications. As a result, these findings should be generalized to a broader population with caution. Second, the proportion of elderly patients was relatively low in the entire cohort, which may have resulted in an overestimation of the life expectancy estimates. Finally, because this study retrospectively tracked patient survival through the national health insurance system, it was unable to provide a definitive cause of death, including whether it was due to cancer or another disease. However, despite these limitations, we cautiously believe that this study, as the first to analyze the life expectancy of early gastric cancer, might provide a foundation for future large-scale registry studies.

In conclusion, the current study provided detailed life expectancy information stratified by age, sex, and type of gastrectomy utilizing a large cohort of patients with stage 1 gastric cancer. Given that the life expectancy of the patient groups in this study is largely comparable to the general population, there is hope that this research will contribute to alleviating some of the uncertainties and anxieties experienced by patients after a diagnosis of early gastric cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: C.S.K.Data curation: J.H.Y., M.W.Y., B.S.K., I.S.L., C.S.G.Formal analysis: S.H.M., S.O.K.Investigation: B.O.S, C.S.K.Writing - original draft: B.O.S, S.G.O. Writing - review & editing: S.G.O., C.S.K.

Funding

This study was funded by the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (grant number: KGCA032022R2).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to governmental policies regarding individual information. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Seul Gi Oh and Ba Ool Seong contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ahn, H. S. et al. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br. J. Surg.98, 255–260. 10.1002/bjs.7310 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Korean gastric cancer association-led nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancers in 2019. J. Gastric Cancer. 21, 221–235. 10.5230/jgc.2021.21.e27 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, I. J. Gastric cancer screening and diagnosis. Korean J. Gastroenterol.54, 67–76. 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.2.67 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, K. S. et al. Effect of endoscopy screening on stage at gastric cancer diagnosis: results of the national cancer screening programme in Korea. Br. J. Cancer. 112, 608–612. 10.1038/bjc.2014.608 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jun, J. K. et al. Effectiveness of the Korean national cancer screening program in reducing gastric cancer mortality. Gastroenterology152, 1319–1328. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.029 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, H. H. et al. Effect of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy vs open distal gastrectomy on long-term survival among patients with stage I gastric cancer: the KLASS-01 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol.5, 506–513. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6727 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, W. et al. Decreased morbidity of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy compared with open distal gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer: short-term outcomes from a multicenter randomized controlled trial (KLASS-01). Ann. Surg.263, 28–35. 10.1097/sla.0000000000001346 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim, Y. G. et al. Effects of screening on gastric cancer management: comparative analysis of the results in 2006 and in 2011. J. Gastric Cancer. 14, 129–134. 10.5230/jgc.2014.14.2.129 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, W. Y., Cheng, H. C., Wang, J. D. & Sheu, B. S. Factors that affect life expectancy of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.11, 1595–1600. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.036 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Union for International Cancer Control. TNM classification of malignant tumours. UICC (2018). https://www.uicc.org/resources/tnm

- 11.Keyfitz, N. & Flieger, W. World Population Growth and Aging: Demographic Trends in the late Twentieth Century 2nd edn (University of Chicago Press, 1991).

- 12.Morgagni, P. et al. Gastric stump carcinoma after distal subtotal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: experience of 541 patients with long-term follow-up. Am. J. Surg.209, 1063–1068. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.06.021 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nozaki, I. et al. Incidence of metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after synchronous multiple cancer surgery. Gastric Cancer. 17, 61–66. 10.1007/s10120-013-0261-y (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katai, H. et al. Survival outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA or IB gastric cancer (JCOG0912): a multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol.5, 142–151. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30332-2 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalff, M. C. et al. Sex differences in tumor characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of gastric and esophageal cancer surgery: nationwide cohort data from the Dutch upper gi cancer audit. Gastric Cancer. 25, 22–32. 10.1007/s10120-021-01225-1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, W. Y. et al. Smoking status and subsequent gastric cancer risk in men compared with women: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. BMC Cancer. 19, 377. 10.1186/s12885-019-5601-9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nam, S. Y., Jeon, S. W., Kwon, Y. H. & Kwon, O. K. Sex difference of mortality by age and body mass index in gastric cancer. Dig. Liver Dis.53, 1185–1191. 10.1016/j.dld.2021.05.006 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh, D. D., Oh, S. T., Yook, J. H., Kim, B. S. & Kim, B. S. Differences in the prognosis of early gastric cancer according to sex and age. Th. Adv. Gastroenterol.10, 219–229. 10.1177/1756283X16681709 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi, I. J. et al. Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer. N Engl. J. Med.378, 1085–1095. 10.1056/NEJMoa1708423 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukase, K. et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet372, 392–397. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim, S. H. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol.13, 104. 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo, L. W. et al. Analysis of endoscopic screening compliance and related factors among high risk population of upper gastrointestinal cancer in urban areas of Henan Province from 2013 to 2017. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 54, 523–528. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20200304-00238 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, Z., Bai, B., Xie, F. & Zhao, Q. Distal versus total gastrectomy for middle and lower-third gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg.53, 163–170. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.047 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanabe, K. et al. Predictive factors for body weight loss and its impact on quality of life following gastrectomy. World J. Gastroenterol.23, 4823–4830. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4823 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenborn, N. L., Blackford, A. L., Joshu, C. E., Boyd, C. M. & Varadhan, R. Life expectancy estimates based on comorbidities and frailty to inform preventive care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.70, 99–109. 10.1111/jgs.17468 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunobe, S. et al. Surgical outcomes of elderly patients with stage I gastric cancer from the nationwide registry of the Japanese gastric cancer association. Gastric Cancer. 23, 328–338. 10.1007/s10120-019-01000-3 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endo, S. et al. The comparison of prognoses between total and distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in elderly patients >/= 80 years old. Surg. Today. 53, 569–577. 10.1007/s00595-022-02599-0 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jongh, C. et al. Distal Versus Total D2-Gastrectomy for gastric Cancer: a secondary analysis of Surgical and Oncological outcomes Including Quality of Life in the Multicenter Randomized LOGICA-Trial. J. Gastrointest. Surg.27, 1812–1824. 10.1007/s11605-023-05683-z (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, J. B. et al. Effect of comorbidities on postoperative complications in patients with gastric cancer after laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy: results from an 8-year experience at a large-scale single center. Surg. Endosc. 31, 2651–2660. 10.1007/s00464-016-5279-x (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to governmental policies regarding individual information. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.