Abstract

Puerto Rico has endured multiple natural disasters in recent years, including Hurricanes Irma and Maria (2017), earthquakes (2019), and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), which placed significant strain on its healthcare system. This study examined trends in health care utilization for injuries, infectious diseases, and mental health services across Puerto Rico’s health regions from 2016 to 2022. Using private claims data from four major insurers, we analyzed trends in health care utilization rates per 1,000 beneficiaries across seven health regions. Infectious disease claims rose significantly following each disaster, with the sharpest increases observed post-2020, particularly in the Caguas region. Mental health and substance use claims exhibited a consistent upward trend across all health regions, with Caguas and Ponce reporting the largest increases. Injury claims declined in 2020 but rebounded in most regions by 2021, with Caguas consistently reporting the highest rates. These findings highlight the substantial and varied impacts of consecutive disasters on health care utilization in Puerto Rico, particularly for infectious diseases and mental health services. Notable regional disparities, such as higher utilization rates in Caguas, underscore the need for interventions to strengthen health system resilience and ensure equitable healthcare access in preparation for future disasters.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-89983-1.

Keywords: Puerto Rico, Disasters, Health Care utilization, Mental Health Services, Infections, Injuries

Subject terms: Health care, Health policy, Health services, Public health

Introduction

Puerto Rico’s geographic location and climate make it highly vulnerable to natural disasters, which, in recent years, have taken a toll on both its infrastructure and public health1–3. The island has faced several significant disasters, including Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, the 2019–2020 earthquake series, the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020, and Hurricane Fiona in 2022. These events occurred within a relatively short time span, compounding stress on an already fragile healthcare system4–6.

Hurricane Maria, one of the most devastating storms in Puerto Rico’s history, caused widespread damage to infrastructure and severely disrupted health services, leading to increased morbidity and mortality7–14. Subsequent disasters, including the earthquakes in late 2019 and early 2020, further destabilized health resources15–17. These events in Puerto Rico, including the more recent Hurricane Fiona that created catastrophic flooding, have led to increased rates of bacterial infections (e.g., leptospirosis) and vector-borne diseases (e.g., dengue) from contaminated and stagnant waters18,19. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these challenges, placing unprecedented demands on the health system, particularly in terms of infectious disease and injury management and mental health services20–23. The compounded effects of these crises highlight the critical need to understand how healthcare utilization shifts in response to disasters16,24,25.

In addition to the acute disruptions caused by disasters, the longer-term impact on preventive healthcare services, such as routine checkups, is particularly concerning. Following Hurricane Maria, routine checkup rates declined significantly, with disparities observed across demographic groups and health regions26. This decline in preventive care highlights the cascading effects of disasters on healthcare access, which often linger far beyond the immediate recovery period. Additionally, the availability of mental health crisis services has shown growing inequities in Puerto Rico compared to U.S. states, both before and after Hurricanes Maria and Irma21. These inequities disproportionately affect indigent patients, underscoring the need for tailored strategies to strengthen mental health service delivery during and after disasters27–29.

Furthermore, changes in Puerto Rico’s healthcare workforce have compounded the challenges of healthcare delivery during disaster recovery. Physician shortages have been exacerbated by ongoing migration of healthcare professionals to the U.S. mainland, driven by economic instability and limited resources on the island23,30. This issue has created significant regional disparities in healthcare availability, as health regions such as Fajardo and Ponce struggle to maintain sufficient physician coverage1,2. These challenges are particularly acute during disaster recovery periods, where the need for both primary care and specialized services increases31.

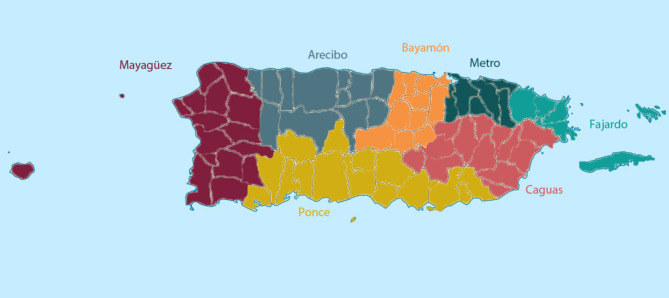

Previous studies have explored the impact of individual disasters on healthcare systems in Puerto Rico, but little is known about the cumulative effects of consecutive disasters on health care utilization over time, particularly from the perspective of regional disparities32. Health regions are groupings of municipalities defined by the Puerto Rico Department of Health1,33. A map of health regions can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Map of Puerto Rico Health Regions as Defined by the Puerto Rico Department of Health.

Health regions across Puerto Rico differ in terms of population density, healthcare infrastructure, access to resources, and exposure to the different disasters, all of which may influence how they respond to large-scale disruptions1–3. Regional differences in healthcare infrastructure further exacerbate the challenges posed by disasters. For instance, the Metro San Juan region, as the island’s main metropolitan area, benefits from the largest population, prevalence of healthcare providers, and number of facilities. In contrast, more remote health regions such as Fajardo, which includes the island municipalities of Vieques and Culebra, face extreme physician shortages, creating significant barriers to healthcare access, particularly during disaster recovery1.

A recent study examining hospital capacity and utilization in Puerto Rico from 2010 to 2020 found significant variation by health regions, with some regions experiencing declines in hospital beds and occupancy rates, while other regions showed sustained or increased utilization34. These findings suggest that trends in hospital services are not uniform across Puerto Rico, highlighting disparities in healthcare infrastructure that may exacerbate challenges during disaster events. For instance, Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico through the Caguas region, a predominantly mountainous area that received the storm’s initial impact of heavy winds and catastrophic flooding35. Similarly, the epicenter of the 2020 earthquakes was closest to the Ponce region, which endured substantial infrastructural damage17. These disasters compounded existing disparities, creating unique challenges for each region based on their healthcare infrastructure and geographic vulnerability.

This study examines the cumulative impact of consecutive disasters on healthcare utilization in Puerto Rico across seven health regions from 2016 to 2022. By analyzing private health insurance claims data, which represent nearly 40% of the population, we focus on key service categories: infectious diseases, injuries, and mental health services36. While previous studies have examined individual disasters and their localized effects on Puerto Rico’s healthcare system, this study uniquely addresses the cumulative and compounding impacts of multiple disasters over time. By systematically examining regional disparities and healthcare utilization trends, it provides critical insights into both the resilience and vulnerabilities of Puerto Rico’s health regions in the face of recurring crises. This analysis contributes to the growing body of disaster research by highlighting the differentiated impacts of compounding crises on healthcare access and outcomes, offering critical insights for disaster preparedness and policy interventions in similarly vulnerable health regions.

Methods

Data

We obtained repeated, cross-sectional 2016–2022 data through the Puerto Rico Office of the Insurance Commissioner (OCS, for their Spanish name), which included data from the four private insurance plans in compliance with the Affordable Care Act in Puerto Rico: First Medical, Plan de Salud Menonita, Triple S Salud, and MCS37. Health care utilization from each insurer was provided separately by year, health region, specific categories, including injury, infectious disease, and mental health and substance use claims. MCS, Triple S Salud, and Plan de Salud Menonita also provided data for an aggregate measure of all infectious, injury, and mental health and substance use claims per 1,000 beneficiaries. First Medical did not have data for all infectious disease, all injury, and all mental health and substance use claims per 1,000 beneficiaries. We calculated these data points by summing together the number of specific claims within each category for each region and year. A list of all the infectious diseases, injuries, and mental health and substance use claims that were captured by the aggregate variables can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The OCS data did not provide total counts of infectious disease, injury, and mental health and substance use claims per region and year. Instead, they provided the data in the form of number of claims per 1,000 beneficiaries. Therefore, to aggregate infectious disease, injury, and mental health and substance use data for each insurer into one estimate per region per year, we multiplied the number of claims per 1,000 beneficiaries by the number of beneficiaries for each insurer, per region and year. Then, we divided this number by 1,000 to calculate the number of claims for each insurer in each region in each year. Third, we summed the total number of claims per region and year across all insurers to calculate the total number of claims made in a given region and year. Next, we calculated the total number of beneficiaries in each region for each year across all insurers. Finally, to calculate a combined number of claims per 1,000 beneficiaries, we divided the total number of claims per region and year by the total number of beneficiaries per region and year and multiplied by 1,000.

Ethical considerations

This study analyzed publicly available data about hospital characteristics aggregated at the health region level. Therefore, this study was not considered to be human subjects research by the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus institutional review board.

Measures

The variables of interest for these analyses included number of infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries, number of injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries, and number of mental health and substance use claims per 1,000 beneficiaries.

Analysis

After calculating the combined number of claims per 1,000 beneficiaries across all insurers, we used Stata MP 18 to graph these rates by health region over time to model trends and examine regional differences in healthcare utilization across Puerto Rico. We used linear regression to predict each variable of interest from an interaction between region and year. Using Stata’s margins and lincom commands, we calculated the differences in trends over time for each health region. Because each health region had only a single estimate per year, it was not possible to calculate measures of uncertainty.

Results

Infectious disease claims

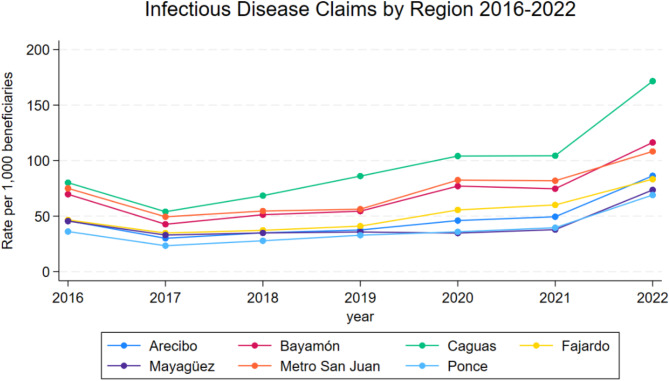

Infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries by region from 2016 to 2022 can be found in Table 1 and shown in Fig. 2. Infectious disease claims decreased across all health regions from 2016 to 2017. From 2017 to 2021, infectious disease claims steadily rose until they surpassed 2016 numbers. There was a sharp increase in infectious disease claims from 2021 to 2022 for all health regions. Caguas had the largest increase in infectious disease claims from 2016 to 2022. In 2022, Caguas had 91.5 more infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries compared to 2016. In comparison, the other health regions had increases from 2016 to 2022 that ranged from 28 to 46.6. Additionally, across all years, Caguas always had the highest number of infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries compared with the other regions. The number of infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in Caguas ranged from 54 up to 171.6 from 2016 to 2022. The regions with the next highest number of infectious disease claims were Metro San Juan and Bayamón, that ranged between 49.4 and 108.3 and 42.7 and 116.3 claims per 1,000, respectively, in the same time frame. Ponce, Arecibo, and Mayagüez had the lowest number of infectious disease claims per 1,000 beneficiaries across all years.

Table 1.

Infectious Disease claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries across Health Regions, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

| Number of beneficiaries per 1,000 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Arecibo | 45.9 | 30.0 | 34.9 | 37.5 | 46.0 | 49.4 | 86.3 |

| Ref. | −15.8 | −10.9 | −8.4 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 40.4 | |

| Mayaguez | 45.5 | 32.9 | 34.8 | 35.7 | 34.7 | 37.8 | 73.5 |

| Ref. | −12.6 | −10.7 | −9.8 | −10.8 | −7.7 | 28.0 | |

| Bayamon | 69.7 | 42.7 | 51.2 | 54.4 | 77.0 | 74.6 | 116.3 |

| Ref. | −27.0 | −18.5 | −15.3 | 7.3 | 5.0 | 46.6 | |

| Metro San Juan | 75.0 | 49.4 | 54.6 | 56.2 | 82.4 | 81.8 | 108.3 |

| Ref. | −25.6 | −20.5 | −18.8 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 33.3 | |

| Caguas | 80.1 | 54.0 | 68.4 | 86.0 | 104.1 | 104.4 | 171.6 |

| Ref. | −26.1 | −11.7 | 5.9 | 24.0 | 24.3 | 91.5 | |

| Ponce | 36.1 | 23.3 | 27.8 | 32.8 | 35.9 | 39.5 | 69.0 |

| Ref. | −12.8 | −8.3 | −3.3 | −0.23 | 3.4 | 32.9 | |

| Fajardo | 46.5 | 34.7 | 37.2 | 41.0 | 55.6 | 60.1 | 83.3 |

| Ref. | −11.8 | −9.3 | −5.5 | 9.0 | 13.6 | 36.8 | |

Fig. 2.

Trends in Infectious Disease Claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries Across Health Regions in Puerto Rico, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

Injury claims

Injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries by region from 2016 to 2022 can be found in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 3. There was a small, but considerable drop in injury claims from 2019 to 2020 across all health regions. In 2019, injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries ranged from 19.6 to 38.3, while in 2021 they ranged from 17.6 to 32.2. However, in 2021, injury claims rose again to be at or near 2016 levels for all health regions except Caguas. Caguas is the only health region that had considerably higher injury claims in 2021 compared to 2016 (6.8 claims per 1,000 beneficiaries higher). All other regions had fewer or about the same number of injury claims in 2021 compared to 2016 (range: −4.5 to 1.1). In 2022, most regions in Puerto Rico had fewer injury claims compared to 2016, apart from Caguas and Fajardo. Fajardo had 1.5 more injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2022 compared to 2016, and Caguas had 8.1 more injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2022 compared to 2016. Once again, across all the years, Caguas always had the highest number of injury claims compared to the other regions. Injury claims in Caguas ranged from 32.2 to 42.8 in the 2016–2022 period. In comparison, the region with the second highest number of injury claims was Metro San Juan, which ranged 22.6 to 27.2 injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in the same period. Arecibo and Fajardo had the lowest number of injury claims per 1,000 beneficiaries across most years.

Table 2.

Injury claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries across Health Regions, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

| Number of beneficiaries per 1,000 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Arecibo | 19.6 | 19.8 | 18.5 | 19.6 | 17.6 | 19.6 | 19.5 |

| Ref. | 0.16 | −1.1 | 0.0 | −2.1 | 0.0 | −0.1 | |

| Mayaguez | 26.8 | 25.5 | 25.3 | 23.3 | 18.8 | 22.2 | 22.5 |

| Ref. | −1.3 | −1.4 | −3.5 | −8.0 | −4.5 | −4.3 | |

| Bayamon | 23.9 | 23.1 | 22.0 | 23.7 | 20.5 | 25.1 | 23.4 |

| Ref. | −0.8 | −2.0 | −0.2 | −3.4 | 1.1 | −0.5 | |

| Metro San Juan | 30.4 | 30.3 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 22.6 | 28.2 | 27.2 |

| Ref. | 0.0 | −3.6 | −3.6 | −7.8 | −2.2 | −3.1 | |

| Caguas | 34.7 | 34.8 | 35.7 | 38.3 | 32.2 | 41.5 | 42.8 |

| Ref. | 0.1 | 1.1 | 3.7 | −2.5 | 6.8 | 8.1 | |

| Ponce | 22.1 | 21.3 | 20.3 | 21.7 | 18.1 | 22.7 | 20.1 |

| Ref. | −0.8 | −1.7 | −0.4 | −4.0 | 0.6 | −2.0 | |

| Fajardo | 19.4 | 21.9 | 20.3 | 21.5 | 17.9 | 20.3 | 20.9 |

| Ref. | 2.6 | 0.9 | 2.1 | −1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | |

Fig. 3.

Trends in Injury Claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries Across Health Regions in Puerto Rico, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

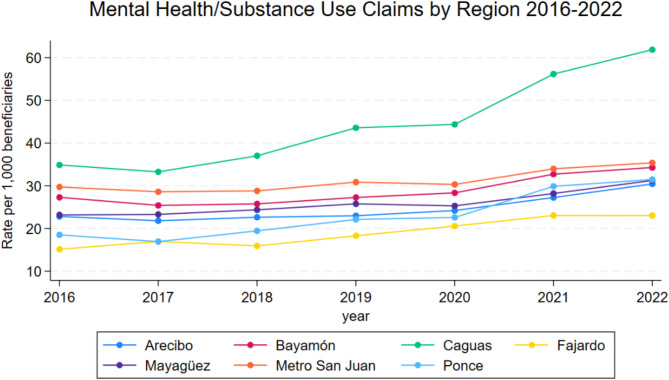

Mental and substance use claims

Mental health and substance use claims per 1,000 beneficiaries by region from 2016 to 2022 can be found in Table 3 and shown in Fig. 4. Overall, mental health and substance use claims have risen from 2016 to 2022 across all health regions. Caguas and Ponce had larger increases in mental health and substance use claims from 2020 to 2021 compared with the other health regions. Caguas had 11.8 more claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2020 compared to 2021, and Ponce had 7.3 more claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in 2020 compared to 2021 (data not shown in table). Increases in mental health and substance use claims from 2020 to 2021 for all other regions ranged from 2.4 to 4.4 claims per 1,000 beneficiaries (data not shown in table). Again, Caguas had the highest number of mental health and substance use claims per 1,000 beneficiaries across years compared to the other health regions. Mental health and substance use claims in Caguas ranged from 33.3 to 61.9 claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in the 2016 to 2022 period. The region with the next highest number of mental health and substance use claims was Metro San Juan which had 28.6 to 35.4 claims per 1,000 beneficiaries in the same period. Fajardo had the fewest mental health and substance use claims across most years, ranging from 15.1 to 23 claims per 1,000 beneficiaries.

Table 3.

Mental Health claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries across Health Regions, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arecibo | 22.8 | 21.8 | 22.6 | 23.0 | 24.2 | 27.2 | 30.4 |

| Ref. | −1.0 | −0.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 4.4 | 7.6 | |

| Mayaguez | 23.2 | 23.3 | 24.4 | 25.8 | 25.3 | 28.2 | 31.3 |

| Ref. | 0.1 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 5.0 | 8.1 | |

| Bayamon | 27.3 | 25.4 | 25.8 | 27.3 | 28.3 | 32.7 | 34.3 |

| Ref. | −1.9 | −1.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 5.4 | 7.0 | |

| Metro San Juan | 29.7 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 30.9 | 30.3 | 34.0 | 35.4 |

| Ref. | −1.1 | −0.9 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 4.3 | 5.7 | |

| Caguas | 34.9 | 33.3 | 37.0 | 43.6 | 44.4 | 56.2 | 61.9 |

| Ref. | −1.6 | 2.1 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 21.3 | 27.0 | |

| Ponce | 18.5 | 16.9 | 19.4 | 22.1 | 22.6 | 29.9 | 31.5 |

| Ref. | −1.6 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 11.4 | 13.0 | |

| Fajardo | 15.1 | 17.0 | 15.9 | 18.3 | 20.6 | 23.0 | 23.0 |

| Ref. | 1.8 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

Fig. 4.

Trends in Mental Health and Substance Use Claims per 1,000 Beneficiaries Across Health Regions in Puerto Rico, Private Insurance Claims Data, 2016–2022.

Discussion

The findings from these analyses offer important insights into how health care utilization patterns in Puerto Rico have changed in response to recent, consecutive disasters. Notable shifts were observed in infectious disease claims, injury-related healthcare, and mental health service utilization, which provide insight into the compounding effects of these crises on the island’s health system.

One of the clearest findings is the surge in infectious disease claims following Hurricane Maria and the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in regions like Caguas. While the sharp rise in claims post-2020 is likely attributable to the pandemic, the lingering effects of previous disasters, such as damaged infrastructure and reduced health care access, may have exacerbated vulnerability to infectious diseases. This trend highlights the critical role that healthcare infrastructure plays in disaster resilience18,19,23,24,32. Regions with already strained systems, such as Caguas, may have been less equipped to mitigate the compounded health risks posed by consecutive disasters.

Injury claims showed a different pattern. While there was a decline in injury claims from 2019 to 2020, which is likely related to the COVID-19 pandemic and reduced activity during lockdowns, most regions saw a rebound by 2021. However, regions such as Caguas consistently reported the highest number of injury claims throughout the study period, which suggests that this region may have unique vulnerabilities, possibly due to population density, infrastructure, or other social determinants of health1,5,34. The variation in injury claims across regions could also reflect differences in local responses to disasters and the effectiveness of regional healthcare services in managing trauma and injury-related incidents9,12,13,22.

Mental health and substance use claims exhibited a consistent upward trend across all regions, with Caguas and Ponce seeing the largest increases. For Ponce, the post-2020 increase in claims could be attributed to compounded earthquake effects, given that this region was closest to the earthquake’s epicenter and experienced more infrastructural damage as a result17. This trend underscores the mental health challenges faced by Puerto Ricans in the aftermath of repeated disasters, a finding consistent with broader research on the psychological toll of large-scale crises15,21,27–29. The mental health burden may linger long after the immediate physical impacts of a disaster have subsided, emphasizing the need for sustained mental health support, particularly in regions heavily affected by these events16. The rise in claims during and after the COVID-19 pandemic further suggests that mental health services remain under significant pressure.

This study highlights important regional disparities in health care utilization during disaster periods34. Regions like Caguas consistently exhibited higher utilization rates across multiple health services, which may be attributable to several underlying factors. Residents of Caguas could have higher baseline health care needs, limited access to preventive services, or infrastructure that was particularly vulnerable and less abile to withstand the impact of disasters. Furthermore, socioeconomic factors such as poverty, employment instability, and healthcare access may have contributed to these disparities4,5,38. Addressing these disparities requires tailored interventions that consider the unique vulnerabilities of each region, with particular focus on enhancing healthcare infrastructure and preparedness in regions like Caguas.

Conversely, regions such as Arecibo and Fajardo displayed lower healthcare utilization rates across most services. While this could suggest that these regions were less impacted by disasters, it could also reflect reduced access to healthcare, potentially due to geographic or economic barriers1,34. These findings point to the need for a deeper investigation into how social determinants of health, such as income, health care access, and health insurance coverage, influence disaster response and recovery in Puerto Rico.

Implications for disaster preparedness and healthcare resilience

The trends observed in this study underscore the critical importance of enhancing disaster preparedness and health system resilience in Puerto Rico. The surge in health care utilization following disasters highlights the strain placed on the territory’s health care resources, which could be mitigated by more robust infrastructure, better resource allocation across regions, and enhanced emergency response capabilities4–6,31. The sustained rise in mental health claims calls for a comprehensive strategy to integrate mental health care into disaster response efforts. This would involve increasing access to mental health services, particularly in regions like Caguas and Ponce, where the demand has surged21,39. Additionally, addressing injury-related healthcare needs is critical, particularly in regions like Caguas, where the burden of injuries remained consistently high. Disaster preparedness strategies should incorporate plans for handling trauma and injury care during and after crises, with an emphasis on rapid response and access to necessary services9,22,24,40.

The findings underscore the need for interventions to improve healthcare system resilience, particularly in regions like Caguas and Ponce, which experienced higher health service demands. Policymakers and planners must prioritize resource allocation to these vulnerable regions to enhance infrastructure, increase access to mental health services, and ensure preparedness for managing injuries and infectious diseases during and after disasters4,5,16,21,22. The consistent regional disparities suggest that one-size-fits-all disaster response strategies may be inadequate. Instead, tailored approaches that account for each region’s unique vulnerabilities, population density, and healthcare infrastructure are critical for strengthening disaster resilience and ensuring equitable access to care during crises.

Limitations

The use of aggregated data at the health region level prevents more detailed analyses of individual-level healthcare utilization, which limits our ability to account for demographic factors such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status; these could influence healthcare needs and access. Additionally, the repeated cross-sectional design only allows for trend analyses over time and does not permit causal conclusions about the specific impact of each disaster. Future research should incorporate individual-level data and use more advanced longitudinal methods to better understand the causal relationships between disasters and health care utilization patterns. Integrating geospatial data and social determinants of health could provide deeper insights into the factors driving regional disparities. Comparative analyses between Puerto Rico and other disaster-prone regions could provide valuable insights into best practices for building resilient health systems in the face of consecutive crises.

Conclusion

This study highlights the substantial and varied impacts that consecutive disasters had on health care utilization in Puerto Rico from 2016 to 2022, a period where multiple and compounding disasters occurred in the territory. Our findings reveal significant increases in mental health and injury claims, as well as notable regional disparities in health service utilization, particularly in Caguas and Ponce. These results emphasize the urgent need for disaster preparedness strategies tailored to the unique healthcare needs of Puerto Rico’s health regions. This study provides new insights into the cumulative effects of consecutive crises on healthcare systems and underscores the importance of continued research on the long-term impacts of natural disasters. As climate-related and other crises continue to pose significant threats, ensuring that Puerto Rico’s healthcare system is equipped to respond to and recover from future disasters is more urgent than ever.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

DLM performed the data analysis. JPS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study conception, interpretation of findings, and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers R01MD013866 and R01MD016426. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMHD. The funders had no role in study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data must be obtained through the Puerto Rico Office of the Commissioner of Insurance https://www.ocs.pr.gov/ (Email: cumplimiento@ocs.pr.gov).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study analyzed publicly available data about hospital characteristics aggregated at the health region level. Therefore, this study was not considered to be human subjects research by the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus institutional review board.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Evidence Indicates a Range of Challenges for Puerto Rico Health Care System. (2017). https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/evidence-indicates-range-challenges-puerto-rico-health-care-system

- 2.Perreira, K., Lallemand, N., Napoles, A. & Zuckerman, S. Environmental Scan of Puerto Rico’s Health Care Infrastructure. (2017). https://www.urban.org/research/publication/environmental-scan-puerto-ricos-health-care-infrastructure

- 3.KFF. Puerto Rico: Fast Facts. (2017). https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/puerto-rico-fast-facts/

- 4.Benach, J., Díaz, M. R., Muñoz, N. J., Martínez-Herrera, E. & Pericàs, J. M. What the Puerto Rican hurricanes make visible: Chronicle of a public health disaster foretold. Soc. Sci. Med.238, 112367 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy, D. & Cheatham, A. Puerto Rico: A U.S. Territory in Crisis. (2025). https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/puerto-rico-us-territory-crisis

- 6.Currie, C. P. Puerto Rico Disasters: Progress Made, but the Recovery Continues to Face Challenges. (2024). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105557

- 7.Kishore, N. et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl. J. Med.379, 162–170 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orengo-Aguayo, R., Stewart, R. W., de Arellano, M. A., Suárez-Kindy, J. L. & Young, J. Disaster exposure and Mental Health among Puerto Rican youths after Hurricane Maria. JAMA Netw. Open.2, e192619 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferré, I. M. et al. Hurricane Maria’s impact on Punta Santiago, Puerto Rico: Community needs and Mental Health Assessment six months Postimpact. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 13, 18–23 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnette, D., Kim, K. & Kim, S. Gender-related measurement invariance on the self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20) for global mental distress with older adults in Puerto Rico. Arch. Public. Health Arch. Belg. Sante Publique. 82, 163 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scaramutti, C., Salas-Wright, C. P., Vos, S. R. & Schwartz, S. J. The Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 13, 24–27 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Madera, S. L. et al. The impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s health system: post-disaster perceptions and experiences of health care providers and administrators. Glob Health Res. Policy. 6, 44 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandra, A. et al. Health and Social Services in Puerto Rico before and after Hurricane Maria: Predisaster conditions, Hurricane damage, and themes for recovery. Rand Health Q.9, 10 (2021). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos-Burgoa, C. et al. Differential and persistent risk of excess mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico: a time-series analysis. Lancet Planet. Health. 2, e478–e488 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collazo, G. et al. A retrospective cohort study on the Increasing Trend of Suicide Ideations and risks in an opioid-dependent Population of Puerto Rico 2015–2018. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 24, 1367–1370 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera, F. I. et al. Compound crises: the Impact of Emergencies and Disasters on Mental Health Services in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 21, 1273 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Elst, N., Hardebeck, J. & Michael, A. Potential Duration of Aftershocks of the 2020 Southwestern Puerto Rico Earthquake. (2020). 10.3133/ofr20201009

- 18.Barrera, R. et al. Impacts of hurricanes Irma and Maria on Aedes aegypti populations, aquatic habitats, and Mosquito infections with Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses in Puerto Rico. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.100, 1413–1420 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, F. K. et al. Leptospirosis Outbreak in Aftermath of Hurricane Fiona — Puerto Rico, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep.73, 763–768 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García, C., Rivera, F. I., Garcia, M. A., Burgos, G. & Aranda, M. P. Contextualizing the COVID-19 era in Puerto Rico: compounding disasters and parallel pandemics. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci.76, e263–e267 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purtle, J. et al. Growing inequities in mental health crisis services offered to indigent patients in Puerto Rico versus the US states before and after hurricanes Maria and Irma. Health Serv. Res.58, 325–331 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia, I. et al. Health-related nonprofit response to concurrent disaster events. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.82, 103279 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruz, N. I., Santiago, E. & Alers, R. I. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Surgical Workload of the UPR-affiliated Hospitals. 42, (2023). [PubMed]

- 24.Smith, E. C., Burkle, F. M., Aitken, P. & Leggatt, P. Seven decades of disasters: a systematic review of the literature. Prehospital Disaster Med.33, 418–423 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldmann, E. & Galea, S. Mental Health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 35, 169–183 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stimpson, J. P., Mercado, D. L., Rivera-González, A. C. & Ortega, A. N. Trends in routine checkup within the past year following a hurricane. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 17, e430 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell, P., Edwards, B. & Gray, M. Exposure to multiple natural disasters and externalising and internalising behavior: a longitudinal study of adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health. 76, 89–95 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barlattani, T. et al. Patterns of psychiatric admissions across two major health crises: L’ Aquila earthquake and COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. BMC Psychiatry. 24, 658 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, S. T., Mason, S. M., Erickson, D., Slaughter-Acey, J. C. & Waters, M. C. Predicting Post-disaster post-traumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories: the role of Pre-disaster traumatic experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 21, 749 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varas-Díaz, N. et al. On leaving: coloniality and physician migration in Puerto Rico. Soc. Sci. Med.325, 115888 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padilla, M. et al. Red tape, slow emergency, and chronic disease management in post-María Puerto Rico. Crit. Public. Health. 32, 485–498 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salas, R. N. et al. Impact of extreme weather events on healthcare utilization and mortality in the United States. Nat. Med.30, 1118–1126 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coss-Guzmán, M. & Román-Vázquez, N. Informe Mensual de Suicidios En Puerto Rico. (2021).

- 34.Stimpson, J. P. et al. Trends in hospital capacity and utilization in Puerto Rico by health regions, 2010–2020. Sci. Rep.14, 17849 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Major Hurricane Maria - September 20, (2017). https://www.weather.gov/sju/maria2017 (2017).

- 36.Private Health Insurance Coverage by Type and & Characteristics, S. U.S. Census Bureau (2023).

- 37.Plans in Compliance with the Affordable Care Act and the Health Insurance Code. (2025). https://www.ocs.pr.gov/en-us/seguros-de-salud/cubiertas/2025/cubiertas-individuales

- 38.Rivera-González, A. C. et al. The impact of Medicaid funding structures on inequities in health care access for latinos in New York, Florida, and Puerto Rico. Health Serv. Res.57 (Suppl 2), 172–182 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivera-González, A. C., Purtle, J., Kaholokula, J. K., Stimpson, J. P. & Ortega, A. N. Maui Wildfire and 988 suicide and Crisis Lifeline call volume and capacity. JAMA Netw. Open.7, e2446523 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stimpson, J. P., Wilson, F. A. & Jeffries, S. K. Seeking help for disaster services after a flood. Disaster Med. Public. Health Prep. 2, 139–141 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data must be obtained through the Puerto Rico Office of the Commissioner of Insurance https://www.ocs.pr.gov/ (Email: cumplimiento@ocs.pr.gov).