Abstract

The Bmp proteins are a paralogous family of chromosomally encoded Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. They have similar predicted immunogenicities and similar electrophoretic mobilities by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. P39 reactivity against Borrelia burgdorferi lysate in immunoblots of Lyme disease patients has long been identified with reactivity to BmpA, but responses to other Bmp proteins have not been examined. To determine if patients with Lyme disease developed such responses, immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-Bmp reactivity in patient and control sera was studied by using soluble recombinant Bmp (rBmp) proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. Although some patient sera contained IgG immunoblot and immunodot reactivities against all four Bmp proteins, analysis of IgG anti-Bmp fine specificity by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with graded doses of soluble homologous and heterologous rBmp proteins showed that only the responses to BmpA, BmpB, and BmpD were specific. This suggests that at least three of the four Bmp proteins are expressed by B. burgdorferi in infected patients and that specific antibodies to them are likely to be present in the P39 band in some patients.

During the course of Lyme disease, patients develop antibodies directed against many Borrelia burgdorferi cellular components (18). For serologic testing by immunoblotting, reactivity to the P39 band is diagnostically helpful (6). It has been widely assumed that the borrelial protein BmpA, encoded by the bmpA gene (17), is uniquely responsible for P39 reactivity in Lyme disease patient sera, even though tests with recombinant BmpA (rBmpA) were found to be less sensitive than those with whole-cell lysates (15).

BmpA is a member of the paralogous Bmp protein family, encoded by the tandemly located bmp genes on the linear B. burgdorferi chromosome (9). The bmp genes are conserved in the DNA sequence and genetic structure in all B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains (10) and are constitutively expressed in vitro (13). Expression of bmpD is modulated during coculture with tick cells (3); expression of bmpA (but not the other bmp genes) is modulated during infection in mice (12). The Bmp proteins have putative lipidation sites at their N termini, 37 to 52% amino acid identities to each other, and similar predicted molecular weights and immunogenicities (9). Their functions are unknown.

It is also not known if Bmp protein expression is modulated during human infections. Unfortunately, the need for at least 1 μg of borrelial RNA for current microarray analyses makes application of this technology difficult for diseases such as human Lyme disease where the number of organisms in specimens is low. The similar predicted molecular weights of the individual Bmp proteins would make it difficult to distinguish between them by one-dimensional immunoblotting of B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysates. The presumptively low levels of BmpB, BmpC, and BmpD in B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysates (8) also hinder the collection of purified native materials for analysis of the antibody responses to and the specificities for individual Bmp proteins. In order to provide evidence for the possible expression of multiple Bmp proteins by B. burgdorferi during human infections, we have used recombinant Bmp (rBmp) proteins, immunoglobulin G (IgG) immunoblotting and immunodotting, and a competitive IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine whether patients with Lyme disease produce antibodies specific for individual members of the Bmp protein family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples.

A convenience sample of sera from 15 patients from New York State diagnosed with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans was tested. Only a single baseline serum sample was available for seven of these patients; baseline and sequential convalescent-phase serum samples (32 serial samples) were available for the other eight. These patients received antimicrobial treatment at the baseline visit. An additional four serum samples that tested positive for IgG antibodies by a licensed B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysate immunoblot assay (PGLI; MarDx Diagnostics, Carlsbad, Calif.) (2) were also evaluated. The clinical findings for this patient group are unknown. Control sera were obtained from 18 healthy volunteers and from 6 patients with diagnoses other than Lyme disease (urinary tract infection, viral syndrome, depression, personality disorder, facial palsy). All sera were kept at −20°C until they were tested. This study was determined to be exempt from the requirement for institutional review board review and approval by New York Medical College.

Cloning of bmp genes.

Complete bmp genes (9) were amplified by PCR from B. burgdorferi B31 (ATCC 35210) DNA by using the forward and reverse primers listed in Table 1. The amplified fragments were cloned into pQE40 (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.) by using SphI-SmaI restriction sites (bmpA) or into pET30 Xa/LIC (Novagen, Madison, Wi.) (bmpB, bmpC, bmpD) by using ligation-independent cloning, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Escherichia coli M15 (QIAGEN) was used for expression of rBmpA fused with dihyrofolate reductase and the six-His tag; E. coli BL21-CodonPlus-RIL (Strategene, Austin, Tex.) was used for rBmpB, rBmpC, and rBmpD fused with the six-His tag (16). Calcium chloride-competent E. coli M15(pREP4) cells were transformed with purified pQE40 (QIAGEN) bmpA, while calcium chloride-competent E. coli BL21-CodonPlus-RIL were transformed with each of the purified pET Xa/LIC derivatives. Colonies of E. coli transformants were screened for recombinant protein with mouse anti-five-His tag monoclonal antibodies (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and colonies expressing high levels of recombinant protein were selected. To confirm the sequence of bmp genes in the transformed bacterial clones used to produce the rBmp proteins, plasmid DNA from each of three E. coli colonies expressing high levels of each rBmp protein was purified and sequenced. No variations in amino acid sequence from those in GenBank were obtained with the recombinant plasmids for bmpA, bmpB, or bmpC. In one of the three bmpD plasmids examined, the DNA sequence had a transversion from T to C that resulted in an amino acid substitution from Glu to Lys. Because it was present in only one of three subclones, this substitution would appear to represent a mutation unique to this particular subclone that was not present in the original transformed parental strain and thus be unlikely to affect the antigenicity of the expressed recombinant protein that was used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Primers and conditions used for production of rBmp proteins

| Gene | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Vector | Restriction sites used | E. coli strain | Conditionsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bmpA | ACATGCATGCGCTTTGTTTGTAAAGGGGAAATCGT | pQE40 | SphI, SmaI | M15 [pREP] | 30°C to 0.9 OD600 and then stimulation with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C |

| TCCCCCCGGGCAATTATTCAAACAAAACCAATG | |||||

| bmpB | GGTATTGAGGGTCGCAATGGAGAAGTGCTTTATATGAGAA | pET30 Xa/LIC | —b | BL21-CodonPlus-RIL | 37°C to 0.7 OD600 and then stimulation with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C |

| AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCAATTTCATATTCCTCCTGATTGCA | |||||

| bmpC | GGTATTGAGGGTCGCAGGAGAGGATTAATTTTGTTTAAAAGA | pET30 Xa/LIC | — | BL21-CodonPlus-RIL | 37°C to 0.7 OD600 and then stimulation with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C |

| AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCTCCCCTTTACAAACAAAGCTATA | |||||

| bmpD | GGTATTGAGGGTCGCAAGGAGGATATTTTTATGTTAAA | pET30 Xa/LIC | — | BL21-CodonPlus-RIL | 37°C to 0.9 OD600 and then stimulation with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C |

| AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCATTTTCCATTTGCAAAACAAAGTTA |

IPTG, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

—, ligation-independent cloning.

Expression and purification of rBmp.

rBmp proteins were expressed from transformed E. coli grown at 30°C or 37°C in 2YT medium and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 2 h at 37°C (Table 1). After cell lysis, inclusion bodies were collected by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-0.05% Triton X-100, and solubilized in 7 M urea-10 mM dithiothreitol. rBmp proteins were purified on HisBind Quick columns (Novogen), refolded in PBS-0.05% Triton X-100, and concentrated to the original volume by dialysis against Ficoll 400 (molecular biology grade; Sigma). Approximately 70% of rBmpA, rBmpB, and rBmpD and 50% of rBmpC were solubilized by this protocol. Precipitated recombinant proteins were discarded and not used in further studies. Following gel filtration on 16/60 Superdex 200 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.) with PBS-0.05% Triton X-100, rBmp purity was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and silver staining.

Immunoblotting and dot immunobinding.

For IgG immunoblotting, purified rBmp proteins were electrophoresed on a 10 to 20% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose by semidry blotting, and replicate lanes were either silver stained or blocked and incubated with patient sera. Blots were developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) and tetramethylbenzidine blotting (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, Ill.). For IgG immunodotting (dot immunobinding), recombinant protein (500 ng) was dissolved in SDS-PAGE loading buffer; adsorbed to nitrocellulose; and after it was blocked, incubated with patient sera. Immunodots were developed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and ECF technology (Amersham Biosciences) (11). Each blot contained positive and negative control dots. The last serum dot (patient or control) that gave a visual signal greater than that of negative control dot was scored as positive.

Competitive indirect fluorescent IgG ELISA.

Competitive indirect fluorescent ELISA was performed in duplicate by using 96-well plates containing adsorbed 100-ng aliquots of rBmp proteins or control protein fractions from E. coli containing the plasmid vector with or without the dihydrofolate reductase gene insertion (13). Diluted sera were mixed with serial dilutions of rBmp competitor, bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma), or E. coli lysate (final concentrations of competitors or controls, 1 to 64 μg/ml) (7). The mixtures were incubated at 23°C for 2 h and were then added to wells coated with one of the rBmp proteins for a further 4 h at 23°C. After the wells were washed, the wells were developed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG and 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (ICN Biomedicals, Irvine, Calif.), and the fluorescence intensity was measured (Fluorescence Concentration Analyzer; IDEXX, Westbrook, Maine). The competition in wells containing BSA and E. coli lysate never exceeded 10%; the competition seen with BSA was subtracted from the fluorescence intensity obtained with rBmp proteins. All sera showed 100% inhibition of ELISA reactivity after incubation with an excess of the homologous rBmp protein. Values from individual assays were normalized by comparison to the antigen control wells (7). The results are reported as percent inhibition of binding by heterologous competitors at the 50% inhibitory dose (IC50) for binding to the adsorbed homologous rBmp protein. Competitive inhibition of IgG anti-rBmp ELISA activity was analyzed statistically by analysis of variance with a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison posttest; the level of significance was set at a P value of <0.01. There were two situations in which a response was defined as cross-reactive, depending on whether the inhibition of reactivity of serum by a heterologous Bmp ligand used at the IC50 of the homologous Bmp ligand was >50% or <50%. A response was considered cross-reactive if inhibition of reactivity by heterologous ligand was >50% (heteroclitic cross-reactivity) (7). A response was also considered cross-reactive if inhibition of reactivity by heterologous ligand was <50%, but the inhibition was not significant (P < 0.01) (7). The competitive ELISA was done in duplicate on two independent occasions. The results from these separate experiments were reproducible and were combined.

Statistical analysis.

The concordance of the results between immunoblotting and dot immunobinding assays was analyzed by McNemar tests; the level of significance was set at a P value of <0.05. The differences in the reactivities of patient and control sera with rBmp proteins were analyzed by Fisher's exact test; the level of significance was set at a P value <0.01. Confidence limit intervals were computed by the modified Wald method (1).

RESULTS

Reactivities of rBmp proteins with patient sera.

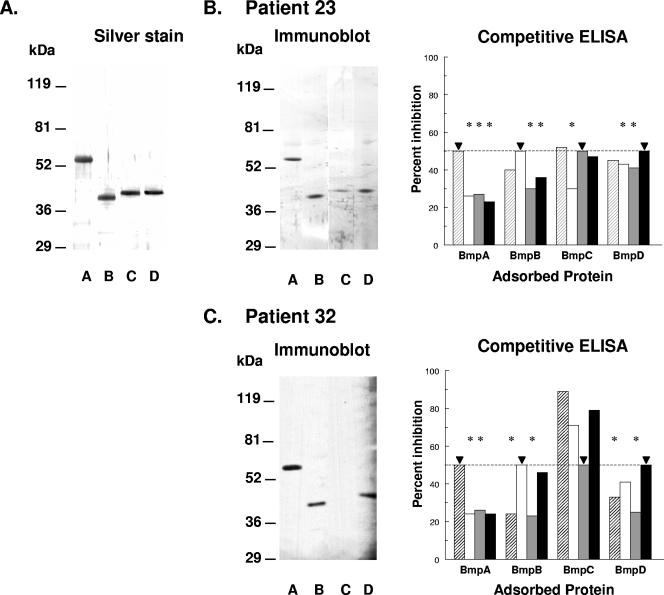

The expressed rBmp proteins were purified by chelate-affinity chromatography and gel filtration. SDS-PAGE and silver staining showed that these proteins were >98% pure (Fig. 1A). Some patient sera were reactive with all four rBmp proteins on immunoblotting (Fig. 1B, patient 23); others were reactive with none, one, two, or three of these proteins. As an example of the latter group, the serum from patient 32 reacted with rBmpA, rBmpB, and rBmpD but not with rBmpC (Fig. 1C). The purity of the rBmp proteins permitted them to be used in an IgG immunodot assay. Paired results from rBmp IgG immunoblot and IgG immunodot assays with 10 serum samples from eight Lyme disease patients, 4 PGLI serum samples, and 6 control serum samples revealed no significant discordance (P > 0.05), consistent with the detection of similar epitopes by both assays. In the entire group of 39 serum samples from 15 patients with early Lyme disease examined by IgG immunodotting, 10 did not react with any rBmp protein, 6 reacted only with rBmpA, 1 reacted only with rBmpC, 5 reacted only with rBmpD, and the remaining 17 reacted with two to four rBmp proteins (Table 2). Of the four PGLI serum samples, all reacted with rBmpA, one reacted with rBmpB, and two reacted with rBmpD (Table 2). Despite the fact that some serum samples did not react with any rBmp protein in IgG immunodotting, at least one serum sample from each of the 15 patients with early Lyme disease (100%) contained IgG anti-Bmp reactivity to at least one of the four rBmp proteins, while only six serum samples from the 24 control patients (25%) contained any such reactivity (P < 0.0001).

FIG. 1.

Purified B. burgdorferi rBmpA (lane A), rBmpB (lane B), rBmpC (lane C), and rBmpD (lane D) proteins (1.5 μg) were separated by 10 to 20% SDS-PAGE, electrolytically transferred to nitrocellulose, and (A) silver stained or analyzed for IgG antibodies to Bmp proteins by immunoblotting and competitive ELISA with sera from (B) patient 23 (early Lyme disease) or (C) patient 32 (IgG clinical laboratory immunoblot positive). For the competitive IgG ELISA, the sera were first incubated with the indicated soluble rBmp protein shown by the bars (rBmpA, striped bars; rBmpB, white bars; rBmpC, gray bars; rBmpD, black bars), and their ELISA reactivities with the adsorbed rBmp protein (horizontal axis) were then determined. The results are shown as percent inhibition of ELISA reactivity at 50% inhibition (dashed line) with the soluble homologous rBmp protein (▾). *, reactivity significantly less than reactivity at 50% inhibition with the homologous rBmp protein (P < 0.01, analysis of variance with Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison posttest). The molecular weight of rBmpA is much higher than those of the other rBmp proteins because of fusion of the BmpA sequence to dihydrofolate reductase and the six-His tag. The other rBmp proteins contained only the six-His tag fused to their respective Bmp sequences, and their molecular weights are therefore closer to those of the native proteins. See Materials and Methods for details of the assays.

TABLE 2.

Immunodot reactivities to rBmp proteins of 39 serum samples from 15 patients with early Lyme disease, 4 PGLI serum samples, and 24 control serum samples

| Group | No. of serum samples reactive with the indicated rBmp protein(s)a:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | A only | B only | C only | D only | A, B | A, D | B, D | C, D | A, B, C | A, B, D | A, C, D | B, C, D | A, B, C, D | |

| Early Lyme disease | 10 (5) | 6 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0 | 5 (3) | 3 (3) |

| PGLIb | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Controls | 18 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Number of sera reacting with the indicated rBmp protein (number of patients providing sera). Numbers in parentheses sum to >15 because some serum samples from some patients who provided serial samples showed no reactivity with any Bmp protein, while others reacted with one or more Bmp proteins. A, BmpA; B, BmpB; C, BmpC; D, BmpD.

PGLI, positive for IgG antibodies in a licensed B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysate immunoblot assay.

Antibody fine specificity to individual Bmp proteins.

In order to determine if this extensive Bmp reactivity represented only cross-reactivity to these highly homologous proteins, IgG anti-Bmp fine specificity was analyzed by competitive ELISA with graded doses of soluble homologous and heterologous rBmp proteins (7). Competitive IgG ELISA with 18 serum samples from 10 patients with early Lyme disease showed that 5 (28%) contained specific antibodies only to BmpA, 1 (6%) contained specific antibodies to BmpA and to BmpB, 2 (11%) contained specific antibodies to BmpA and to BmpD, and 2 (11%) contained specific antibodies only to BmpB (Table 3). No serum sample contained specific antibodies to BmpC (95% confidence limit interval, 0 to 18%). The remaining eight serum samples contained antibodies that displayed multiple cross-reactivities for Bmp proteins (Table 3). In three PGLI serum samples, two contained antibodies specific only for BmpA and one contained antibodies that showed multiple cross-reactivities for Bmp proteins (Table 3). Disagreement between the reactivity with rBmp proteins determined by immunoblotting and immunodotting and the specificity of this reactivity determined by competitive ELISA occurred with all of the 21 serum samples tested by both methods. An example of this disagreement is a serum sample from patient 23 with early Lyme disease. It reacted with all four rBmp proteins by IgG immunoblotting (Fig. 1B), but only its IgG anti-BmpA ELISA reactivity was BmpA specific. Its BmpB reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpA, its BmpC reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpA and BmpD, and its BmpD reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpA (Fig. 1B). A second example of this disagreement between reactivity with rBmp proteins in immunoblotting and competitive ELISA is shown in Fig. 1C. Although a PGLI serum sample from patient 32 reacted with rBmpA, rBmpB, and rBmpD by immunoblotting (Fig. 1C), its BmpA reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpD, its BmpB reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpD, its BmpC reactivity was cross-reactive with all three other Bmp proteins, and its BmpD reactivity was cross-reactive with BmpB (Fig. 1C).

TABLE 3.

Antibody fine specificity by competitive ELISA to rBmp proteins in 18 serum samples from 10 patients with early Lyme disease and 3 PGLI serum samples

| Group | No. of serum samples (no. of patients) with:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific anti-Bmp reactivitya

|

Cross-reactive anti-Bmp reactivities | |||||||

| None | A only | A, B | A, D | B only | C only | D only | ||

| Early Lyme disease | 10 (8) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 8 (4) |

| PGLIb | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Number of serum samples with the indicated Bmp specificity (number of patients). Numbers in parentheses for the patient samples sum to >10 because some serum samples from patients who provided serial samples contained specific anti-Bmp reactivity, while others contained multiply cross-reactive anti-Bmp reactivities. A, BmpA; B, BmpB; C, BmpC; D, BmpD.

PGLI, positive for IgG antibodies in a licensed B. burgdorferi whole-cell lysate immunoblot assay.

DISCUSSION

Despite the high degree of homology of Bmp proteins and the fact that BmpA (P39) is one of the major B. burgdorferi immunogens (6, 18), immune responses to the other Bmp proteins in Lyme disease patients have not previously been examined. Our data indicate that even though some patients with Lyme disease showed IgG reactivity to all four Bmp proteins by immunoblotting and immunodotting, only reactivities to BmpA, BmpB, and BmpD were specific by competitive ELISA. Because all four native Bmp proteins exhibit similar electrophoretic mobilities, on one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (16), they would be expected to localize in a single band in clinical immunoblots with whole B. burgdorferi lysates. The combination of specific and cross-reactive anti-Bmp antibodies in patient sera and the probable localization of four Bmp proteins to a single band provides a ready explanation for the prominence of the P39 band in clinical immunoblots, despite the relatively low levels of expression of the individual Bmp proteins compared to those of many other borrelial lipoproteins (8, 16).

The reasons for the differences in patient reactivity to the various Bmp proteins are not clear. They could reflect differences in the levels of expression of the Bmp proteins in the human host analogous to the differences in their levels of expression in vitro (3, 8). They could also reflect differences in exposure of the individual Bmp proteins on B. burgdorferi. In this context, the lack of detection of specific antibodies against BmpC might be the result of the low levels of expression of this protein and its lack of exposure on the outer surface of B. burgdorferi (16; J. J. Shin, A. V. Bryksin, H. P. Godfrey, and F. C. Cabello, unpublished data). The small numbers of patients and patient sera examined and the genetic heterogeneity of the human population could also be expected to contribute to the apparent variability of the antibody response to the Bmp proteins.

Approximately 70% of rBmpA, rBmpB, and rBmpD and 50% of rBmpC were solubilized after purification and refolding. The possibility exists that refolding of modified rBmp fusion proteins might affect their three-dimensional structures and therefore the accessibility of Bmp epitopes in ELISA. This in turn might affect the observed reactivity of patient sera to the individual members of this paralogous protein family in the present study. However, it seems more likely that binding of the protein to polystyrene would be a more significant factor in determining epitope availability than the modifications introduced by the fusion partner. Adsorption of proteins to polystyrene is associated with the loss or alteration of antigenic epitopes, the generation of new epitopes, and the loss of antibody affinity compared to those of the same molecules in solution for 90 to 94% of molecules in a sample. However, 6 to 10% of absorbed molecules do not undergo these changes during the process of absorption (4, 5), and it is this small number of unchanged molecules that permits the use of soluble proteins for the analysis of antibody specificity by competitive solid-phase ELISA (4). The complete inhibition of ELISA reactivity following the incubation of patient sera with an excess of the homologous rBmp protein suggests that these sera contained no antibodies able to react with “novel” epitopes caused by binding to polystyrene.

Detection of antibodies specific for BmpA, BmpB, or BmpD suggests that these proteins are expressed in patients infected with B. burgdorferi. It thus complements the results of other studies that have demonstrated bmp gene expression in infected mice (12). Experimental analysis of the modulation of expression of many B. burgdorferi lipoproteins has been done in vivo by the use of genomic methods (14). The relatively simple techniques used in the present study to analyze patient samples are equally valid. They have the further advantage of being directly applicable to conditions such as Lyme disease, where the numbers of bacteria in the tissues are low. They could therefore be used to study the expression of other paralogous protein families of B. burgdorferi in human patients. These studies would clearly be relevant for serologic diagnosis, understanding of Lyme disease pathogenesis, and the design of new vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fred Moy, Ashok Badithe, Carl Hamby, and Sergey Brodsky for helpful discussions and Harriett Harrison for assistance with manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI43063 (to F.C.C.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agresti, A., and B. A. Coull. 1998. Approximate is better than ‘exact’ for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am. Stat. 52:119-126. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. E., J. Nowakowski, S. Bittker, D. Cooper, R. B. Nadelman, and G. P. Wormser. 1996. Evolution of the serologic response to Borrelia burgdorferi in treated patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bugrysheva, J., E. Dobrikova, H. P. Godfrey, M. Sartakova, and F. C. Cabello. 2002. Modulation of Borrelia burgdorferi stringent response and gene expression during extracellular growth with tick cells. Infect. Immun. 70:3061-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler, J. E. 2004. Solid supports in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and other solid-phase immunoassays. Methods Mol. Med. 94:333-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantarero, L. A., J. E. Butler, and J. W. Osborne. 1980. The adsorptive characteristics of proteins for polystyrene and their significance in solid-phase imunoassays. Anal. Biochem. 105:375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1995. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 44:590-591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowther, J. R. 2001. Practical exercises, p. 153-231. In J. R. Crowther (ed.), The ELISA guidebook, vol. 149. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 8.Dobrikova, E. Y., J. Bugrysheva, and F. C. Cabello. 2001. Two independent transcriptional units control the complex and simultaneous expression of the bmp paralogous chromosomal gene family in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 39:370-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser, C. M., S. Casjens, W. M. Huang, G. G. Sutton, R. Clayton, R. Lathigra, W. White, K. A. Ketchum, R. Dodson, E. K. Hickey, M. Gwinn, B. Dougherty, J. F. Tomb, R. D. Fleischmann, D. Richarson, J. Peterson, A. R. Kerlavage, J. Quackenbush, S. Salzberg, M. Hanson, R. van Vugt, N. Palmer, M. D. Adams, J. Gocayne, J. Weidman, T. Utterback, L. Watthey, L. McDonald, P. Artiach, C. Bowman, S. Garland, C. Fujii, M. D. Cotton, K. Horst, K. Roberts, B. Hatch, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1997. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 390:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorbacheva, V. Y., H. P. Godfrey, and F. C. Cabello. 2000. Analysis of the bmp gene family in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J. Bacteriol. 182:2037-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landowski, C. P., H. P. Godfrey, S. I. Bentley-Hibbert, X. Liu, Z. Huang, R. Sepulveda, K. Huygen, M. L. Gennaro, F. H. Moy, S. A. Lesley, and M. Haak-Frendscho. 2001. Combinatorial use of antibodies to secreted mycobacterial proteins in a host immune system-independent test for tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2418-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang, F. T., F. K. Nelson, and E. Fikrig. 2002. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J. Exp. Med. 196:275-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojaimi, C., C. Brooks, S. Casjens, P. Rosa, A. Elias, A. Barbour, A. Jasinskas, J. Benach, L. Katona, J. Radolf, M. Caimano, J. Skare, K. Swingle, D. Akins, and I. Schwartz. 2003. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71:1689-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pal, U., and E. Fikrig. 2003. Adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the vector and vertebrate host. Microbes Infect. 5:659-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roessler, D., U. Hauser, and B. Wilske. 1997. Heterogeneity of BmpA (P39) among European isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and influence of interspecies variability on serodiagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2752-2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin, J. J., A. V. Bryksin, H. P. Godfrey, and F. C. Cabello. 2004. Localization of immunodominant BmpA (P39) on the exposed outer membrane of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 72:2280-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Simpson, W. J., W. Cieplak, M. E. Schrumpf, A. G. Barbour, and T. G. Schwan. 1994. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the gene in Borrelia burgdorferi encoding the immunogenic P39 antigen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 119:381-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steere, A. C., J. Coburn, and L. Glickstein. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Investig. 113:1093-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]