Abstract

The use of synthetic insecticides has been crucial in the management of insect pests however the extensive use of insecticides can result in the development of resistance. Callosobruchus chinensis is a highly destructive pest of stored grains, it’s a major feeder and infests a range of stored grains that are vital to both global food security and human nutrition. We extensively investigated gene expression changes of adults in response to deltamethrin to decipher the mechanism behind the insecticide resistance. The analysis of gene expression revealed 25,343 unigenes with a mean length of 1,435 bp. All the expressed genes were identified, and analyzed by Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment. Exposure to deltamethrin (4.6 ppm) causes 320 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), of which 280 down-regulated and 50 up-regulated. The transcriptome analysis revealed that DEGs were found to be enriched in pathways related to xenobiotics metabolism, signal transduction, cellular processes, organismal systems and information processing. The quantitative real-time PCR was used to validate the DEGs encoding metabolic detoxification. To the best of our knowledge, these results offer the first toxicity mechanisms enabling a more comprehensive comprehension of the action and detoxification of deltamethrin in C. chinensis.

Keywords: Callosobruchus chinensis, Deltamethrin, Resistance, Transcriptome, KEGG, DEGs

Subject terms: Entomology, Animal physiology

Introduction

Seed beetles belonging to the genus Callosobruchus are agricultural insect pests that primarily inhabit tropical and sub-tropical regions1. These pests are known to inflict significant harm to various leguminous crops during the storage phase. The Callosobruchus species that are frequently observed in India include Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), Callosobruchus chinensis (Linnaeus) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), and Callosobruchus analis (Fabricius) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae)2. The infection initially originates in the field, where adult insects deposit eggs on fully developed pods. Subsequently, a secondary infestation occurs during storage after the crops have been harvested. This phenomenon is responsible for significant grain losses, occasionally amounting to as much as 99% within a six-month period3.

Callosobruchus chinensis (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) is a highly destructive pest of stored grains that is widely distributed. It is a major feeder and infests a range of commodities and stored items that are vital to both global food security and human nutrition. C. chinensis exhibits a cosmopolitan distribution pattern and has been observed in numerous countries as a result of the international trade of beans4. The natural habitat of the beetle encompasses the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, where its population has experienced significant growth as a result of the widespread production and distribution of leguminous plants. The spread of these organisms is significantly impacted by their habitat as it is restricted to leguminous plants that provide ideal conditions for reproduction and larval sustenance. Both larvae and adult individuals consume legumes. The common host plants of these organisms encompass green gram, lentil, cowpea, pigeon pea, chickpea, and other pea species, although they have been observed to inhabit numerous more legume hosts5.

The use of synthetic chemical pesticides has been crucial in the management of insect pests in agricultural sites6,7. To combat the menace caused by C. chinensis various chemical and biological control measures have been reported8–11. The extensive use of pesticides can result in the development of insecticide resistance, deterioration of the ecosystem, pollution of subsurface water and soil, and unintended damage to non-target species. For instance, methyl bromide and phosphine are often employed as pesticide chemicals due to their exceptional efficacy in pest management12,13. Insects have successfully adapted to most insecticides by becoming physiologically or behaviourally resistant14,15. In past few years insecticide resistance has been reported in 504 species of insects16,17, and there is still a steady increase in resistance to specific chemicals, with many species now resistant to several families of molecules like DDT, malathion, pirimiphos-methyl, deltamethrin and permethrin18,19.

20,21, has observed that introduction to sub-lethal levels of insecticides can have significant impacts on the reproductive capacity, developmental processes, and chemical susceptibility of insects. These effects have the potential to contribute to the resurgence of pest populations. The enzymes responsible for detoxification, including care, gst, and cest, play a crucial role in the processes of insect resistance. It is imperative to note that an elevation in the activity of these enzymes is essential for effective pesticide metabolism22. Similarly23, reported the expression levels of care, gst, and mfo in Tetranychus urticae (Coleoptera: Tetranychidae) were notably increased 12 h after being exposed to abamectin. In a similar manner, the application of avermectin led to a considerable increase in the activity of care, gst, and mfo in Sogatella furcifera (Coleoptera: Delphacidae). The results of this study suggest that insects have the ability to adjust to the stress caused by avermectin through the activation of their detoxifying enzymes.

Studies have demonstrated that insects with resistance tend to have elevated levels of P450 dependent monooxygenases, which are enzymes that play a role in catalysing reactions involving hazardous substances24,25. The primary mechanism implicated in pesticide resistance of Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) is the augmentation of detoxification processes mediated by cytochrome p450 enzymes. The cyp450 gene cyp6bq9 exhibited a 200-fold increase in expression in the QTC279 strain of T. castaneum that is resistant to deltamethrin. This upregulation implies that cyp6bq9 plays a substantial role in the metabolism of deltamethrin in T. castaneum26. The use of functional genomic and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) techniques has facilitated the identification of a noteworthy upregulation of cyp6bq9 expressions. The numerous impacts of pesticides on insects encompass several sublethal effects, such as alterations in insect behaviour, reproduction, development, and the development of resistance to insecticides. Furthermore, the adaptation of insects to stress caused by insecticides involves a multifaceted metabolic detoxification process that encompasses the involvement of several enzymes.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable advancement in sequencing technology, characterised by an augmentation in the length of sequence reading. Additionally, significant progress has been made in the development of de novo transcriptome assembly software tools, enabling the assembly of transcriptomes in the absence of a reference genome. The aforementioned methodology has been recently employed for the purpose of constructing transcriptomes de novo in a limited number of beetle species27,28. This has provided a valuable resource for conducting gene expression research and investigating the functional properties of genes involved in several biological processes inside this organism at the molecular level. The examination of the genome and transcriptome of C. chinensis has the potential to offer valuable knowledge on the intricate regulatory networks involved in its evolutionary processes. Additionally, such studies may contribute to the development of strategies to enhance resistance to xenobiotics29. The scarcity of available literature on C. chinensis poses significant challenges in comprehending the molecular mechanisms involved in the developmental, physiological, and biochemical features of this insect species. The present study aimed to decipher the effects of deltamethrin exposure against C. chinensis to gain insight into molecular mechanisms of resistance. In a nutshell this study offers valuable molecular information that helps to uncover the potential pathways of resistance following exposure of deltamethrin on C. chinensis.

Materials and methods

Insect maintenance

Adult C. chinensis (3–4 mm length and 2–2.5 mm breadth) were collected from the different granaries of Vadodara, Gujarat and were morphologically identified using standard keys. After identification they were reared in laboratory conditions for at least three months before starting the final experiment, this was the stock culture. The stock culture was reared on host Vigna mungo (green gram) in plastic jars covered with mesh lids30. The cultures were kept under 260−280C and 60–70% RH, 12-h photo period.

Experimental design

A survey was conducted in different insecticide shops and ware houses to find the usage of different insecticides. The unworked or least explored insecticide was taken into the account. A semisynthetic pyrethrin insecticide, technical grade deltamethrin (98% AI, Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) was used. To determine contact toxicity of deltamethrin against C. chinensis, five concentrations of deltamethrin, 6.25, 12.50, 25, 50 and 100 ppm respectively were tested. These concentrations were obtained by dissolving 98% deltamethrin in acetone. A stock solution of 1,000 ppm was made from which other desired concentrations (serial dilutions) were prepared. There were three replicates for each treatment in addition to control. 1 mL of each concentration was placed on the bottom of each petri dish and spread in the entire petri dish (9 cm diameter). After the acetone was evaporated, 10 pairs of adults of C. chinensis were placed into each dish. The same procedure was used for the control treated with acetone. Mortality percentages were recorded after 48 h, 72 h and 96 h of treatment. Thereafter Probit analysis was performed to obtain the LC50value31.

The experiments were performed on two groups. Group I: control (acetone); Group II: treated. 1 mL of control, was evenly spread on the Petri dish (9 cm diameter). After the acetone was evaporated, 10 pairs of newly emerged (1–2 days old) C. chinensis (F1) were released in glass petri dish containing 50 g Vigna mungo (green gram) as host. These petri dishes were maintained at 260−280C, 60–70% RH and 12-h photo period, and they were allowed to mate for 7 days for egg laying. The grains containing eggs were separated and observed for further development. From this eggs, F2 generation individuals were emerged out of which 10 pairs of newly emerged adults were again exposed to sublethal concentration of deltamethrin. Similarly, subsequent generations were obtained and studied, whole set up was replicated three times in all the 6 generations. At the 6th generation, the insects were sacrificed after 7th day of deltamethrin exposure for de novo transcriptome analysis.

RNA isolation and quantification

Total RNA was extracted from the received insect tissue using conventional TRIzol method followed by Column purification using Quick RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research). The quality and quantity of the extracted RNA samples were checked on NanoDrop followed by Agilent Tape station using High Sensitivity RNA ScreenTape. The total RNA was quantified by calculating the ratios of A260/A280 and A260/A230. The samples were confirmed as having good integrity, and the ratios of A260/A280 were between 1.8 and 2.1 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Illumina PE library preparation

The RNA-Seq paired end sequencing libraries were prepared from the QC passed RNA samples using illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA sample Prep kit. Briefly, mRNA was enriched from the total RNA using Poly-T attached magnetic beads, followed by enzymatic fragmentation, 1st strand cDNA conversion using SuperScript II and Act-D mix to facilitate RNA dependent synthesis. The 1st strand cDNA was then synthesized to second strand using second strand mix. The dscDNA was then purified using AMPureXP beads followed by A-tailing, adapter ligation and then enriched by limited number of PCR cycles. The PCR enriched libraries were purified using AMPureXP beads and analyzed on 4200 Tape Station system (Agilent Technologies) using high sensitivity D1000 Screen tape as per manufacturer instructions (Supplementary Fig. 2).

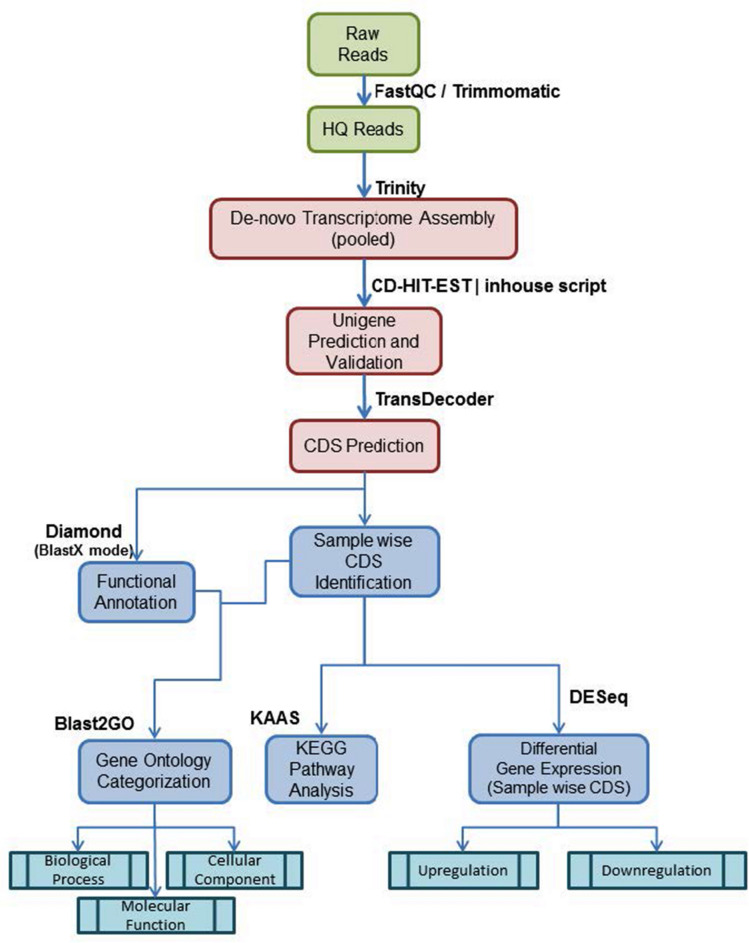

Two samples were sequenced on Illumina platform using 2 × 150 bp chemistry. The sequenced raw data were processed to obtain high quality concordant reads using Trimmomatic v0.39 and an in-house script to remove adapters, ambiguous reads (reads with unknown nucleotides “N” larger than 5%), and low-quality sequences (reads with more than 10% quality threshold (QV) < 25 phred score). The resulting high quality (QV > 25), paired-end reads were used for de novo assembly of the samples. The high-quality reads were assembled together into transcripts using Trinity de novo assembler (version 2.1.1) with a kmer of 25. The assembled transcripts were then further clustered together using CD-HIT-EST-4.8.1to remove the isoforms produced during assembly. This resulted in sequences that can no longer be extended. Such sequences are defined as unigenes. Only those unigenes which were found to have > 85% coverage at 3X read depth were considered for downstream analysis. The whole experiment was replicated three times (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Work flow of the transcriptome summarising all the steps involved in the process.

Coding sequence (CDS) prediction

TransDecoder-v5.3.0 was used to predict coding sequences (CDS) from the unigenes. TransDecoder identifies candidate coding regions within unigene sequences. TransDecoder identifies likely CDS based on the following criteria:

A minimum length open reading frame (ORF) is found in a unigene sequence

A log-likelihood score similar to what is computed by the GeneID software is > 0.

The above coding score is greatest when the ORF is scored in the 1st reading frame as compared to scores in the other 5 reading frames.

If a candidate ORF is found fully encapsulated by the coordinates of another candidate ORF, the longer one is reported. However, a single unigene can report multiple ORFs (allowing for operons, chimeras, etc.).

Functional annotation, Gene ontology and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) analysis

Functional annotation of the pooled CDS was performed using DIAMOND program, which is a BLAST-compatible local aligner for mapping translated DNA query sequences against a protein reference database. DIAMOND (BLASTX alignment mode) finds the homologous sequences for the genes against NR (non-redundant protein database) from NCBI. The annotation procedure was performed with Blast2go version 3.232 and the Trinotate pipeline (https://trinotate.github.io/). The putative genes that were built underwent queries against several databases, such as the NCBI protein database (Nr), Swissprot-Uniprot database, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), EggNog, and InterproScan. The search was performed with BlastX, employing an E-value threshold of 10−5, as described3334. Gene ontology prediction was performed using GOseq35, and orthologous group search is conducted using eggnog v.3.036. The assessment of gene integrity in the assembled transcriptome was performed utilising the BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) library, as outlined in the study37. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) was used to analyze pathways mainly involved in the DEGs38-40. To identify the potential involvement of the predicted CDS in biological pathways, all the identified CDS of 2 samples were mapped to reference canonical pathways in KEGG (T. castaneum (tca), Dendrotonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (dpa), Aethina tumida (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) (atd), Nicrophorus vespilloides (Coleoptera: Silphidae) (nvl), and Drosophila melanogaster(Diptera: Drosophilidae) (dme)) database. The use of the KEGG database and InterProScan software is a key aspect of Blast2GO’s operations41.

Differential gene expression analysis

Differential expression analysis was performed on the CDS between control and treated samples by employing a negative binomial distribution model in DESeqpackage (version1.22.1-http://www.huber.embl.de/users/anders/DESeq/). The CDSs having log2foldchange value greater than zero were considered as up-regulated whereas less than zero as down-regulated. P-value threshold of 0.05 was used to filter statistically significant results.

DEGs validation using quantitative PCR

qRT-PCR was performed to validate DEGs identified via transcriptome sequencing using an Applied Biosystems™ QuantStudio™ 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System. Primer 3.0 software was used to design the gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). OligoEvaluator™ sequence analysis tool was used to study the primer dimer, secondary structure as well as efficiency. qRT-PCR was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (A25741, Applied Biosystems, USA) in Quant Studio 12 K (Life technology) FAST real-time PCR machine with primers to detect selected messenger RNA (mRNA) targets. The melting curve of each sample was measured to ensure the specificity of the products. Beta Actin was used as an internal control to normalize the variability in the expression levels and data was analyzed using 2-∆∆CTmethod42. The mean Ct value for each gene was calculated using three replicates.

Docking and gene interactions

CB-Dock was employed to evaluate the binding affinity of cncc, cyp4c3, gst, gpx, sod and pdi with the insecticide deltamethrin. CB-Dock automates the docking process by integrating AutoDock Vina and employs a predefined algorithm to detect and rank potential binding cavities on the protein structure. Flexible docking is performed by positioning the ligand into the identified cavities, allowing for conformational adjustments to optimize binding. Binding affinities (ΔG in kcal/mol) was calculated using AutoDock Vina, and the docking poses were ranked based on these scores out of which the best ranked pose was selected. The models were built and structure was optimised with the Builder program. Three axis alignment was used and was set to equal grid size along all the three axis. Structure exposed to docking where 10 conformers was considered and the root mean square (rms) cluster tolerance was set to 1.5 Å. The Docking parameters used were GA population size of 150 and maximum number of energy evolutions was 200,000. The obtained score was used to confirm the binding and the identification of residues were deduced. The gene interaction tools STRING and BioGRID were employed to determine the interaction and regulation of the candidate genes with the other associated genes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with GraphPad prism 9.0v followed by multiple comparison test (Tukey’s). Results were presented as Mean ± SEM. The level of significance was set as *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Results

Toxicity of deltamethrin against C. chinensis

LC50value of the deltamethrin was previously obtained31. Supplementary Table 2 depicts the LC50, Slope ± SE, Degree of freedom, chi-square value and P value. The mortality was dependent on total exposure time and concentration. C. chinensis recorded LC50 as 44.38 ppm, 33.77 ppm and 22.93 ppm at 48-h, 72-h and 96-h respectively. The slope values of log concentration probit (lcp) lines of deltamethrin were 4.72, 5.04 and 6.56 at 48-h, 72-h and 96-h respectively.

De novo transcriptome assembly

Whole transcriptome analysis was performed on the two samples; High quality PE data of 2.64 Gb and 3.82 Gb for control and treated samples were generated on Illumina platform using 2 × 150 bp chemistry. After processing the raw reads and high-quality reads (Supplementary Table 3 and 4), finally in the sequencing of C. chinensis transcriptome, it yielded 58,120 transcripts (Table 1). The combined sequences into an assembly that generated 25,343 unigenes with an average length of 1,435 bp and an N50 of 2,045 bp (Table. 1). The size distribution indicated that 13,336 (52.62%) unigene lengths were longer than 1,000 bp (Supplementary Table 5). A total 13,614 CDS were generated with a mean length of 1,190 bp (Table 2). The size distribution indicated that 6,410 (47%) unigene lengths were longer than 1,000 bp (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 1.

Transcript (Pooled) and Validated unigenes (Pooled).

| Description | Transcripts | Unigenes |

|---|---|---|

| No. of Transcripts/Unigenes | 58,120 | 25,343 |

| Total transcript/unigenes length (bp) | 64,282,882 | 36,367,379 |

| N50 (bp) | 1,760 | 2,045 |

| Length of the longest transcript/unigenes (bp) | 20,096 | 20,096 |

| Length of the shortest transcript/unigenes (bp) | 301 | 301 |

| Mean transcript/unigenes length (bp) | 1,106 | 1,435 |

Table 2.

CDS (Pooled).

| Description | CDS |

|---|---|

| No. of CDS | 13,614 |

| Total CDS length (bp) | 16,206,501 |

| Length of the longest CDS (bp) | 17,022 |

| Length of the shortest CDS (bp) | 255 |

| Mean CDS length (bp) | 1,190 |

To identify sample wise CDS from pooled set of CDS, reads from each sample were mapped on the final set of pooled CDS. The read count (RC) values were calculated from the resulting mapping and those CDS having 85% coverage and 3X read depth were considered for downstream analysis for each of the samples. A total 6,596 CDS were generated with a mean length of 1,042 in control sample whereas in case of treated group (HLC50) 11,622 CDS generated with a mean length of 1,257(Table 3).

Table 3.

Sample-wise CDS summary.

| Sr. No | Sample Name | No. of CDS | Total CDS length (bp) | Longest CDS Length (bp) | Shortest CDS Length (bp) | Mean CDS Length(bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | 6,596 | 6,875,946 | 17,022 | 276 | 1,042 |

| 2 | Treated (HLC50) | 11,622 | 14,611,353 | 17,022 | 276 | 1,257 |

Functional annotation

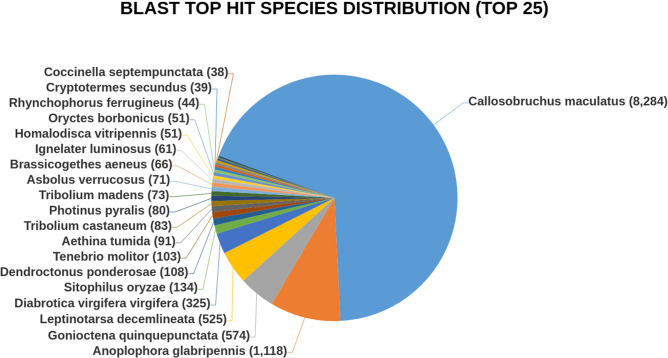

Out of the total 13,614 CDS, 12,629 CDS were functionally annotated and 985 CDS remains without blast (Supplementary Table 7). The blast hits distribution in the Nr database showed most hits (8284) with Callosobruchus maculatus followed by Anoplophora glabripennis (Motschulsky, 1853) (1118), Gonioctena quinquepunctata (F.) (574) and least hits with Coccinella septempunctata (L.) (38) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Depicts top 25 Blast Hit Species distribution of pooled CDS.

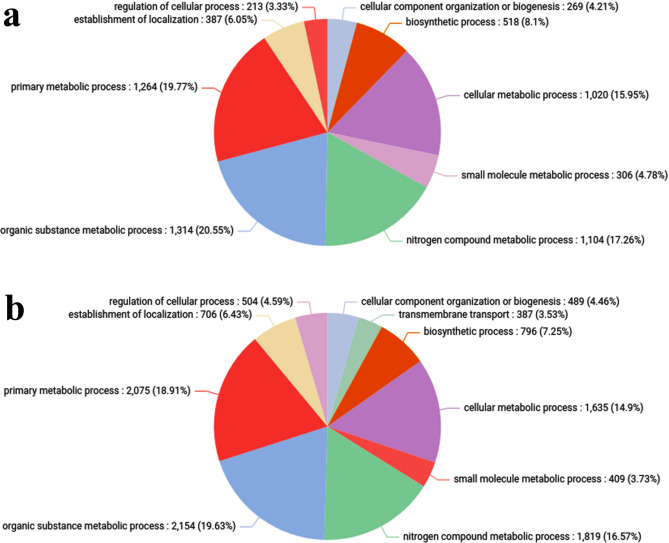

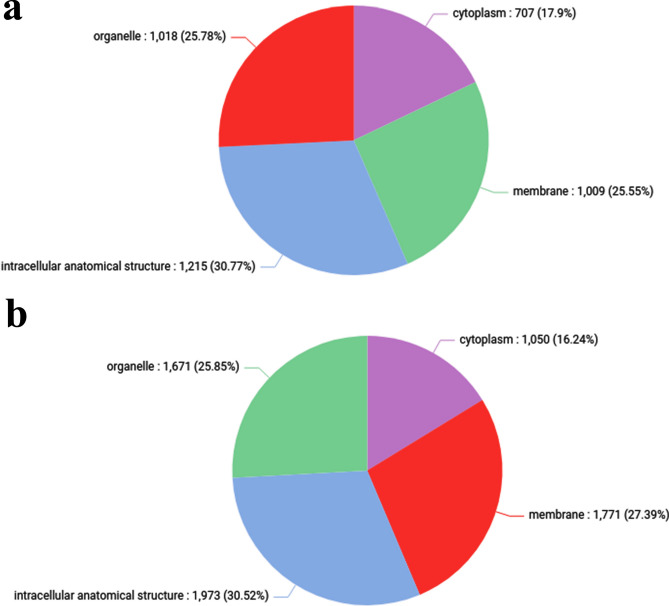

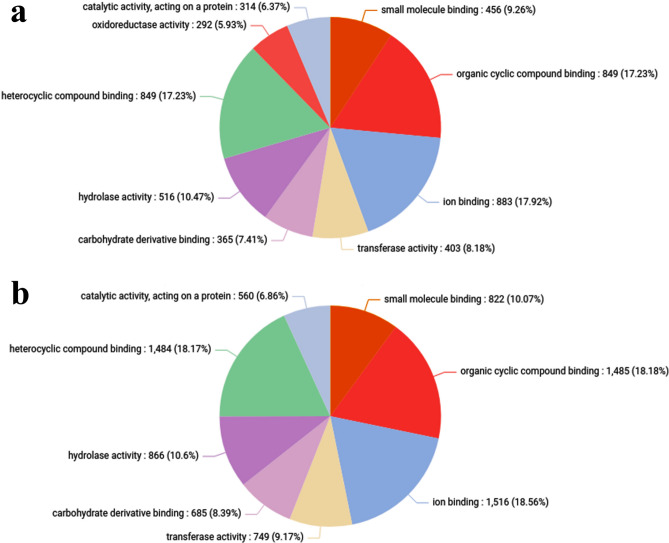

Gene ontology

Overall, 9 biological processes, 4 cellular components, and 8 molecular functions were clustered in control vs treated (HLC50) (Supplementary Table 8). Within the biological processes, most CDS were involved in “organic substance metabolic process” followed by “primary metabolic process”, “nitrogen compound metabolic process” and least CDS in “biogenesis” (Fig. 3). Within the cellular components, “intracellular anatomical structure” and “organelles” respectively were the most prominent ones, whereas cytoplasm was the least prominent (Fig. 4). Moreover, the molecular function, most GO terms were involved in “organic cyclic compound binding” and “ion binding”, respectively, whereas least GO terms were involved in “catalytic activity” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Pie chart depicting the Gene Ontology involved in the biological processes of the C. chinensis (a) Control (b) Treated.

Fig. 4.

Pie chart depicting the Gene Ontology involved in the cellular component of the C. chinensis (a) Control (b) Treated.

Fig. 5.

Pie chart depicting the Gene Ontology involved in the molecular functions of the C. chinensis (a) Control (b) Treated.

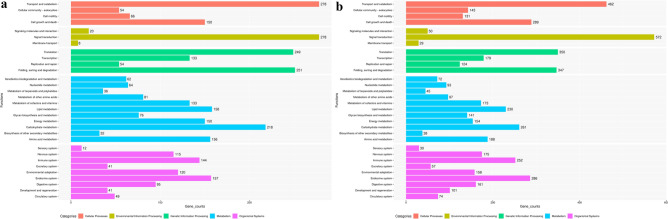

KEGG pathway analysis

The identified CDS for all 2 samples were found to be categorized into 31 KEGG pathways (Supplementary Table 9) under five main categories: Metabolism, Genetic information processing, Environmental information processing, Cellular processes and Organismal systems. The output of KEGG analysis includes KEGG Orthology (KO) assignments and corresponding Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers and metabolic pathways of predicted CDS using KEGG Automated Annotation Server, KAAS. In each pathway, the treated group exhibited a higher gene count compared to the control group. This consistent pattern suggests a robust and widespread effect of the treatment on gene expression in multiple biological pathways. In case metabolic pathway maximum gene count difference in control vs treated was observed in glycan biosynthesis metabolism (158 vs 230) and lipid metabolism (76 vs 141), similarly in xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism (62 vs 72). The study revealed a continuous trend of elevated gene counts in the treated group as compared to the control group in all the pathways associated with the processing of genetic information. Maximum difference was observed in translation (249 vs 350) and folding, sorting and degradation (251 vs 347). Similar elevated gene count was observed in all pathways associated with the processing of environmental information with signal transduction (278 vs 572), signalling molecules and interaction (20 vs 50) and membrane transport (8 vs 29). The aforementioned pattern was discerned throughout all cellular process pathways also with cell organelle process (278 vs 472) and cell division and senescence (150 vs 289). Similarly, the pattern of high gene count in treated group was seen throughout all pathways within the organismal systems also with maximum gene count difference in endocrine system (157 vs 286) and immune system (144 vs 252)(Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

KAAS summary of the CDS involved in different pathways (a. Control and b. Treated) The vertical axis stands for the name of the pathways, and the horizontal axis represents the number of CDS involved (Based on KEGG pathway database383940.

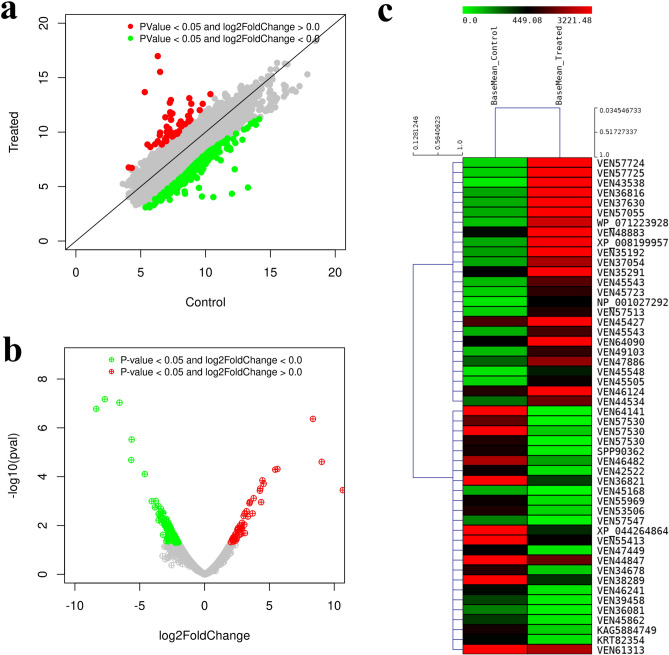

Identification and analysis of DEGs

A total 6282 commonly expressed genes were identified out of which 50 were significantly up-regulated and 280 significantly down-regulated (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

(a) Scatter plot of DEGs between Control and Treated. The horizontal ordinate represents the DEGs in the Control and the vertical ordinate represents the DEGs in the Treated. (b) Volcano plot of DEGs between Control and Treated. The horizontal ordinate represents the fold change of gene expression, and the vertical ordinate represents the statistical significance of the change. Green dots represent the downregulated (significant) and red dots represent the upregulated (significant) genes. (c) Heat map depicting the top 50 differentially expressed genes (significant); Basemean_Control represents the normalized expression values for Control sample and Basemean_Treated represents the normalized expression values for Treated.

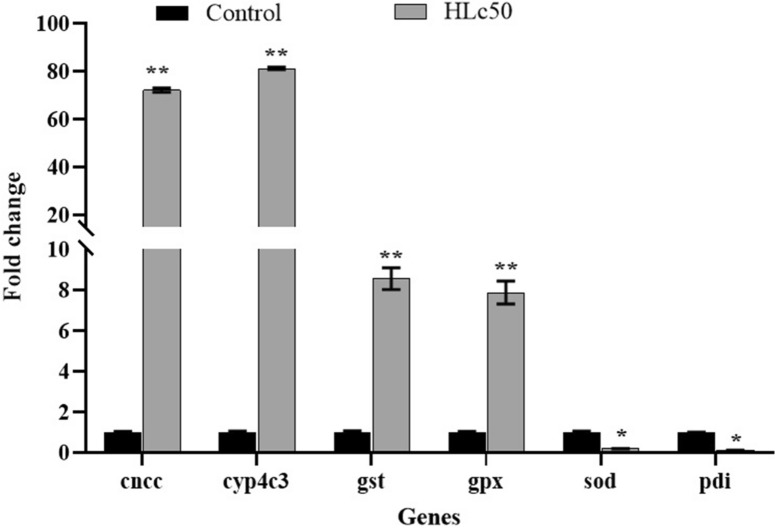

Verification of differentially expressed genes with qRT-PCR

The metabolic detoxification is crucial in the insects to attain insecticide resistance. The current work involved the assessment of gene expressions involved in metabolic detoxification to get insights into the deltamethrin induced resistance on C. chinensis. The findings of this study demonstrated a statistically significant increase (p < 0.01) in the mRNA expression levels of phase I cyp450 genes like cyp4c3, as well as the cncc transcriptomic factor. In a similar vein, the mRNA expression levels of genes such as gst, and gpx were seen to be elevated during phase II. Similarly, downregulation of phase I and II genes like sod and pdi, is also recorded (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

qRT-PCR analysis was performed to validate the DEGs according to RNA-seq. The X-axis represents the selected genes and the Y-axis represents fold change. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

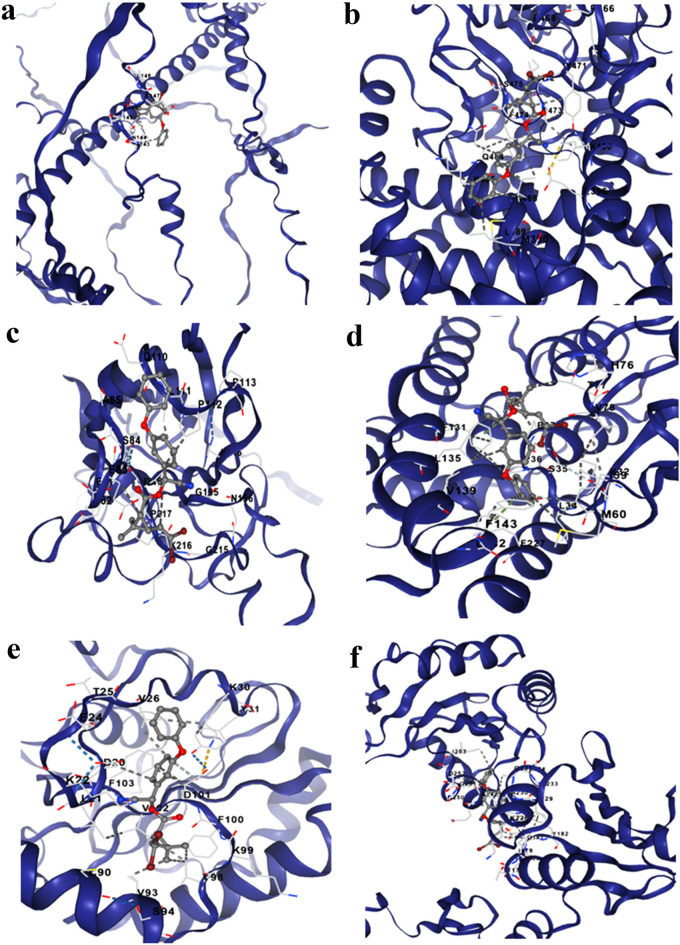

Molecular docking and gene–gene interactions

The binding properties was elucidated by using CBDock, where the score obtained for cncc, cyp4c3, gst, gpx, sod and pdi was −8.1, −9.4, −6.2, −7.9, −7.1, and −6.7 respectively (Supplementary Table 10), out of which the highest binding affinity of deltamethrin was confirmed with gst (Fig. 9). In all the docking structures, deltamethrin was firmly bound to the residues and was dominated by hydrogen bonds and the molecules were located within the pocket. We noted the active residue like K145, K146, N144, L147 for cncc; L389, M390, L396, K400, Y471, F474, S475, Q484, K485 for cyp4c3; E82, E83, S84, A85, D110, L111, P112, G195, K216, P217 for gst interacting with the insecticide (Fig. 9a-c). Similarly, for gpx residues like L34, S35, P36, P37, F131, L135, V139, F143, F227; for sod D101, V102, F103; and for pdi residues K226, A230, G251, D252 were found to be strongly bound to the deltamethrin (Fig. 9d-f). Additionally, we also found that insecticide deltamethrin was fully enclosed by ligand residues in the cavity of all the candidate proteins and were located well within the network of hydrophobic as well as hydrophilic residues.

Fig. 9.

Pictorial representation of the insecticide deltamethrin substrates docked into the binding site of candidate genes (a. cncc, b. cyp4c3, c. gst, d. gpx, e. sod and f. pdi).

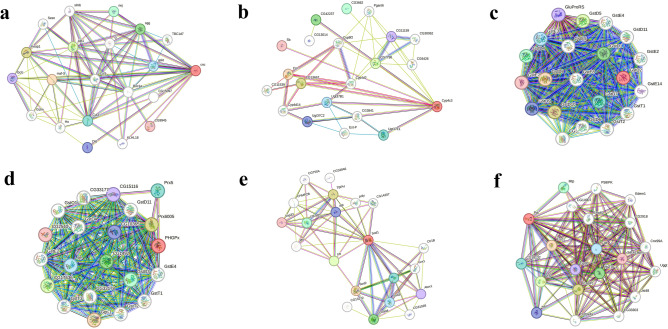

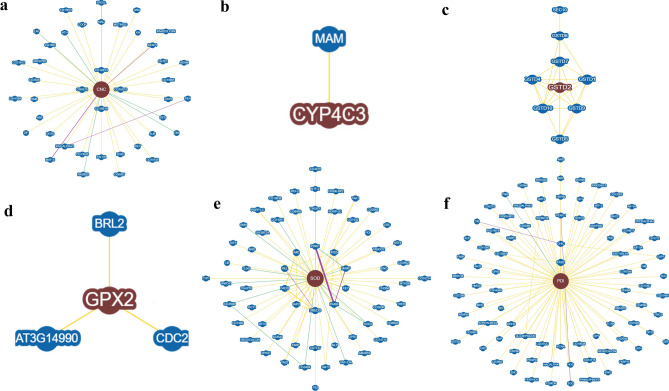

Similarly, to analyse interactions between the specific and non-specific genes and proteins involved at the transcriptional level, an attempt was made to study the interaction of candidate genes with the help of STRING and BioGRID. STRING predicted the top functional partners based on the homology score of all the candidate genes like cncc, showing a close interaction with Maf-S, Keap1, Akt1, sgg, nej, Cul3, gskt, Dfd, Gclc and CG9945 (Fig. 10a; Supplementary Table 11). In cyp4c3 maximum interaction was observed for Cpr, CG1336, CG7798, CG42237, CG3662, Ugt37E1, Ugt37B1, Ugt37C2, CG11159 and sb (Fig. 10b; Supplementary Table 11). In gst it was recorded maximum with GstD8, GstD10, GstD5, GstD1, GstD4, GstD7, GstD3, GstD9, GluProRS and GstE7 (Fig. 10c; Supplementary Table 11). Similarly, in gpx it was observed with Ggt-1, Prx6005, CG17636, CG1492, GstO3, Prx5, se, CG10365, CG15116 and CG2540 (Fig. 10d; Supplementary Table 12). For sod, maximum interaction was observed in Sod2, TBPH, htt, CG5948, cocoon, Ccs, Sod3, apt, Atox1 and Vap33 (Fig. 10e; Supplementary Table 12). In case of pdi it was observed in Ero1L, CaBP1, prtp, Hsc70-3, Mtp, CG18132, Cair, wbl, Gp93 and Sec61alpha (Fig. 10f; Supplementary Table 12) In BioGRID analysis gene gene network of the candidate genes with the associated genes was analysed. A total of 42, 1, 8, 3, 64 and 87 genes were found to be interacted with cncc, cyp4c3, gst, gpx, sod and pdi respectively (Fig. 11a-f).

Fig. 10.

Schematic representation of protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks through STRING (a. cncc, b. cyp4c3, c. gst, d. gpx, e. sod and f. pdi). The green line depicts the gene neighbourhood, red line depicts the gene fusions, blue line depicts gene co-occurrence, light green line depicts the textmining black line depicts the co-expression and the violet line shows the protein homology.

Fig. 11.

Schematic representation of gene–gene interaction networks through BioGRID (a. cncc, b. cyp4c3, c. gst, d. gpx, e. sod and f. pdi). The yellow line depicts the physical edges, green line depicts the genetic edges and purple line depicts the physical/genetic edges.

Discussion

Callosobruchus chinensis is considered a significant pest in the context of pulse crops. Until now, multiple research efforts have focused on exploring the biological and ecological aspects of C. chinensis. Effects of lethal concentrations of pyrethroid against stored grain pest have been extensively studied43–45 However, studies on the toxic effects of pyrethroid are limited. Hence, understanding the mechanisms of insecticide action and effects on the target insect, including potential resistance, is required. A comparative transcriptome study was conducted to compare the gene expression profiles of treated and control C. chinensis. The comprehensive examination of C. chinensis transcriptome resulted in the identification of 58,120 transcripts, of which 25,343 were classified as unigenes. Among these, a total of 13,614 transcripts were determined to be the final coding sequences. The items were classified into distinct functional categories according to their homologous blast results in publicly available databases. The results indicate that 82% of the CDS exhibited a greater degree of similarity with the CDS of C. maculatus, a closely related species. This finding has significance as it can serve as a good point of reference for future investigations into gene function characterisation28.

In the present work, a total of 330 significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were recorded. Previous studies conducted by multiple scientists have reported significant variations in the total DEGs of various insect pests, such as Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and S. cerealella46, 47,48,49, when exposed to insecticides like spinosad, pyrethroid, chlorantraniliprole etc. respectively. The discovery and characterization of DEGs implicated in the action and detoxification of deltamethrin in C. chinensis can offer a viable molecular foundation for understanding the processes behind the toxic effects of insecticide-induced physiological alterations. The findings of the gene ontology (GO) and DEGs indicated a notable enrichment of “metabolic processes” under deltamethrin exposure. Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis was performed to make predictions about the intricate biological functions of the genes that were altered (either up-regulated or down-regulated). This analysis successfully revealed numerous crucial metabolic pathways, such as carbohydrate, amino acid, lipid, energy, and xenobiotic metabolism. The correlation study conducted between GO and KEGG revealed a significant association between certain critical pathways and the hazardous effects induced by deltamethrin. Additionally, gene counts associated with signal transduction and post-translational modifications, under the category of "information processing," exhibited substantial alterations.

Carbohydrate and energy metabolisms provide the primary source of energy for insect activities. Earlier studies have reported the exposure of insecticide that resulted into upregulation or downregulation50,51of the key players in the metabolism of carbohydrate, which suggests that insecticide treatment may have different effects on the carbohydrate metabolism. In our study, we speculate that carbohydrate may play a vital role in the defence against deltamethrin stress. Numerous studies have been conducted on the impact of insecticide treatments on energy metabolism in insects. For example,52 observed that the energy metabolism in resistant olive flies may play a crucial role in facilitating their detoxification process, hence suggesting a potential association with insecticide resistance.

The significance of ATPase in ATP synthesis has been well established53. It has been shown that the expression levels of ATPase are influenced by insecticide treatment. Consequently, ATPase expression may lead to heightened resistance to insecticides. NADPH dehydrogenase and COX, which are integral constituents of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, have been identified as prominent targets of numerous insecticides54. Our investigation revealed that the gene expression levels of ATPase and NADH dehydrogenase was significantly downregulated in C. chinensis upon exposure to deltamethrin, indicating its impact on energy metabolism. Our finding is in agreement with earlier reported55, where they have confirmed a decrease in the energy metabolism components ATPase, NADH dehydrogenase, and COX. These reductions had a negative effect on the growth of the insects.

The metabolism of amino acids plays a crucial role in the synthesis of proteins and the provision of nonessential amino acids and cellular energy. The current study demonstrated a significant enrichment in the metabolic pathways of glycine, serine, threonine, arginine, and proline. These pathways were shown to be related with the enzyme’s dehydrogenase, serine protease, and argininosuccinate synthase. Furthermore, the metabolic pathways of glycine, serine, and threonine, as well as the degradation routes of valine, leucine, and isoleucine, exhibited enrichment. These pathways were shown to be connected with dehydrogenases and acetyltransferases according to56,57. The outcomes of our study exhibited resemblance to the results obtained by55 in their research on Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) subjected to chlorantraniliprole treatment, differential expression of genes associated with amino acid metabolism was observed in insecticide-resistant and -susceptible strains, indicating a potential role in the establishment of insecticide resistance.

Lipid metabolism is the enzymatic process involved in the digestion, absorption, synthesis, and breakdown of fats with the purpose of generating energy58. Significantly, it has been documented that alterations in lipid metabolism have an impact on the growth, development, and reproductive processes of insects59,60. In the present work the KEGG analysis of control vs treated group revealed that the pathways directly involved in lipid metabolism were enriched in glycerolipid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism and fatty acid degradation. Based on the findings of our study, it is postulated that the exposure to deltamethrin induces notable alterations in lipid metabolism and exerts a substantial impact on the growth, development, and reproductive processes of C. chinensis. Further, more research is required to provide a comprehensive understanding of the correlation.

The CDS implicated in signal transduction were mostly categorised under the domain of environmental information processing which was enriched in the mTOR signalling pathway and MAPK signalling pathway-fly. The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathway serves as a fundamental mechanism for the transmission of signals from the extracellular environment to the intracellular space61. In our study, several significant signalling mediator transcripts were detected, such as serine/threonine-protein kinase, insulin-like receptor, MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1, mitogen-activated protein kinase 4, G-protein coupled receptor, tyrosine-protein kinase, nuclear receptor-binding protein, glutamate receptor-interacting protein, ryanodine receptor, and Rho GTPase-activating protein. Additional research is required to investigate the roles and mechanisms of action associated with these signal transduction genes in resistance mechanism.

In the present study posttranslational modifications, protein turnover, and chaperones were impacted by deltamethrin exposure. Many heat shock proteins (Hsps) like Hsp70-6; Hsp68 were upregulated while heat shock 70; co-chaperone protein daf-41; chaperone 2; BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 5 were downregulated. Hsps serve as molecular chaperones and exhibit prompt synthesis in reaction to many environmental stressors, such as cold shock, herbicides, and heavy metals20. Posttranslational modifications play a crucial role in maintaining the functionality of proteins, while protein turnover represents the overall outcome of the ongoing processes of protein synthesis and degradation, which are necessary for the maintenance of properly functioning proteins62. Moreover, chaperones aid in the folding and assembly of proteins, thereby contributing to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in both stressed and unstressed cells63. Hence, it is imperative to do more research on the functioning of Heat Shock Proteins (Hsps) under deltamethrin stress.

The metabolic detoxification system is the major resistance mechanism observed in insects. This mechanism allows insects to efficiently break down or isolate xenobiotics, hence accelerating their degradation process and mitigating their harmful impact. This resistance mechanism enables insects to enhance the production of enzymes, including cyp450s, gsts as a means to counteract the harmful impacts of insecticides64,65. The homologous counterpart of Nrf2, in insects is known as cap ‘n’ collar isoform C (cncc), it plays a crucial function in defending the organism from oxidative stress. This is achieved through the regulation of several stress-responsive genes, while also contributing to resistance to xenobiotics66,67. In this study, in-silico and invitro analysis was carried out and an observation was made regarding the significant (p < 0.01) overexpression of the cyp450 genes, which aligns with previous research findings like26, which also indicated the upregulation of cyp plays a substantial role in the insect’s ability to metabolise insecticides. Similarly,68 discovered that three out of the eight selected cyp genes displayed significant expression levels when the insects were exposed to four different insecticides: cypermethrin, permethrin, cyhalothrin, and lambda imidacloprid. The current study has identified the cncc transcription factors as crucial regulators in the activation of cyp genes and the development of deltamethrin resistance. The observed overexpression of cncc in this study aligns with previous findings by Kalsi et al.66, who reported that cncc functions in a cascade manner when insects are exposed to xenobiotics. The overexpression of cncc leads to the upregulation of phase I cytochrome P450 genes. The results of this study provide additional support for the potential involvement of cyp4c3 in the detoxification and metabolism of deltamethrin in C. chinensis, which was also confirmed by docking studies of cncc (−8.1) and cyp4c3 (−9.4), where a confirmed binding was noted. Additionally, gene networks were also analysed which suggested multiple activation and deactivation of different genes association. This suggest that cncc and cyp4c3 activation leads to phase I detoxification reactions. However, further investigation is required to validate these findings.

GSTs are diverse group of enzymes that plays important role in phase II detoxification process. The insecticides are metabolised by enzymes through a conjugation process with reduced glutathione, resulting in the formation of hydrophobic xenobiotics9,69. GSTs belong to several protein classes in arthropods, including delta, epsilon, sigma, theta, omega, and zeta18,70. In the present work, a confirmed docking score (−6.2) of gst was noted with deltamethrin, and its gene exhibited significant (p < 0.01) upregulation upon exposure to the insecticide. The present study aligns with prior research, as, Song et al.71 observed in their study an upregulation in the expression levels of gstd2 and gstd3 subsequent to the exposure of phoxim and lambda-cyhalothrin exposed T. casteneum. Understanding the process of detoxification mediated by glutathione S-transferase (gst) is crucial in identifying resistance at an early stage, eliminating the specific insecticide prior to the fixation of resistance alleles within populations, and facilitating the development of efficacious insecticide molecules.

Glutathione peroxidase (gpx) is recognised for its ability to neutralise various organic hydroperoxides that are generated during lipid peroxidation (LPO), converting them into their respective hydroxyl molecules29. This process involves the utilisation of glutathione (GSH) and other reducing equivalents. According to72, the enzyme glutathione peroxidase serves as a protective mechanism for cells when exposed to oxidative stress. The observed significant (p < 0.01) upregulation in glutathione peroxidase activity in the current investigation may be attributed to the increased concentration of deltamethrin. Furthermore, it was also confirmed by docking studies (−7.9), where a confirmed binding was recorded, and the gene networks also suggested multiple activation and deactivation of different genes association.

Superoxide dismutase (sod) plays a vital role as an enzymatic component in insects, fulfilling various functions including modulation of immune response, mitigation of damage caused by free radicals, and protection of cellular integrity against adverse environmental factors73,74. Prior research has established that the use of abamectin led to elevated levels of superoxide dismutase (sod) activities in Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)75. Nevertheless, as time elapsed, this sod activities exhibited a gradual restoration towards their initial levels76. The current study observed a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in the expression of the sod gene following exposure to deltamethrin. This finding is consistent with the previous study done by Shan et al.67, which found a negative correlation between pesticide concentration and superoxide dismutase (sod) activity. This was confirmed by the binding (−7.1) of the deltamethrin with sod, where hydrogen bonds were playing a vital part in the interaction. The gene and protein interactions showed a total of 64 genes and 10 proteins suggesting alteration of phase II reactions.

Protein disulphide isomerase (pdi) is a crucial participant in several physiological processes due to its oxidoreductase activity and molecular chaperone function51. The enzyme pdi has the ability to facilitate the creation of disulfide bonds in substrate proteins by means of its oxidoreductase activity. Additionally, pdi is capable of rearranging improperly generated disulfide bonds through its isomerase activity77. Furthermore, pdi exhibits molecular chaperone functionality, hence enhancing the efficiency of protein oxidative folding and mitigating protein aggregation55,78. In this study, we examined the expression of pdi in response to deltamethrin where a significant (p < 0.05) downregulation was recorded. Our findings confirmed a strong binding (−6.7) and the gene and protein interactions showed a total of 87 genes and10 proteins suggesting alteration of phase II reactions. Based on the findings it can be inferred that the pdi may have implications in the antioxidant properties exhibited by C. chinensis. The complete understanding of the molecular processes underlying the metabolic detoxification genes in insecticide resistance remains limited.

The present study represents a significant advancement in our understanding of how gene expression can impact various organismal systems. It has shed light on changes occurring within crucial pathways associated with several fundamental aspects of an organism’s life, including digestion, development and regeneration, immune system, circulatory system, excretory system, nervous system, and sensory system. These findings, however, leave us with intriguing questions about the specific roles and consequences of these alterations. The potential link between these alterations in gene expression and the emergence of insecticide resistance is particularly intriguing. Investigating these connections is of utmost importance, as it can help us develop more effective strategies for managing insect pest populations and mitigating the spread of resistance.

Conclusion

RNA-seq technology has proven to be an effective instrument for investigating the molecular pathways involved in the adverse effects of insecticides. Our study evaluated the effect of deltamethrin on the gene expression changes of C. chinensis using the RNA-Seq technology. De novo transcriptome analysis revealed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were enriched in pathways related to metabolism and information processing, suggesting their involvement in detoxicification mechanisms. The study findings highlight the exposure of deltamethrin in C. chinensis can lead to the upregulation or downregulation of key detoxification-related genes like cncc, cyp4c3, gst, gpx, sod and pdi. These results significantly contribute to our understanding of the activation of detoxification-related genes in C. chinensis and provide insights into the systematic toxicity processes triggered by deltamethrin. In conclusion, the findings of this study may open up exciting avenues for research, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the functions and consequences of these alterations within various organismal systems. This deeper understanding will not only advance our knowledge of basic biology but also have a practical implications in field for the development of novel markers.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, of The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara for providing laboratory facaility. Authors are also thankful to the DBT MSUB-ILSPARE PROJECT & DBT BUILDER CAT III, Cell and Molecular Biology Laboratories of the M. S. University of Baroda and College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Kamdhenu University, Anand, Gujarat for providing instrument facilities. The first author is grateful to the Government of Gujarat for providing the SHODH fellowship.

Author contributions

Pankaj Sharma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – Original Draft. Ankita Salunke and Nishi Pandya: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data curation. Hetvi Shah: In silico analysis. Parth Pandya and Pragna Parikh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository. Raw RNA-Seq data is deposited in FASTQ format to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1058855 and BioSamples accession number SAMN39190691 and SAMN39190692.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly/Quilbot in order to check the grammer and language. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Parth Pandya, Email: parthp@nuv.ac.in.

Pragna Parikh, Email: php59@yahoo.co.in.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-89466-3.

References

- 1.Patole, S. S. Review on beetles (Coleopteran): An agricultural major crop pest of the world. Int. J. Life. Sci. Scienti. Res.3, 1424–1432 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raina, A. K. Callosobruchus spp. infesting stored pulses (grain legumes) in India and comparative study of their biology. Indian J. Entomol.32, 303–310 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalpna, Hajam, Y. A. & Kumar, R. Management of stored grain pest with special reference to Callosobruchus maculatus, a major pest of cowpea: A review. Heliyon8, e08703. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08703 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parish, J. B. et al. Host range and genetic strains of leafminer flies (Diptera: Agromyzidae) in eastern Brazil reveal a new divergent clade of Liriomyza sativae. Agr. For. Entomol.19(3), 235–244. 10.1111/afe.12202 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fite, T. & Tefera, T. The cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and Azuki bean beetle (Callosobruchus chinensis): Major chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) production challenges on smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. J. Basic. Appl. Zool.83, 1–12. 10.1186/s41936-022-00275-w (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damalas, C. A. & Koutroubas, S. D. Farmers’ exposure to pesticides: toxicity types and ways of prevention. Toxics10.3390/toxics4010001 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebadollahi, A., Ziaee, M. & Palla, F. Essential oils extracted from different species of the Lamiaceae plant family as prospective bioagents against several detrimental pests. Molecules25(7), 1556. 10.3390/molecules25071556 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dent, D., & Binks, R. H. Insect pest management. Ed.3 Cabi. Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK. pp363 (2020). 10.1079/9781789241051.0000

- 9.Liu, W. et al. Identification, genomic organization and expression pattern of glutathione transferase in Pardosa pseudoannulata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics10.1016/j.cbd.2019.100626 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pipariya, G., Sharma, P., Pandya, N. & Parikh, P. Insecticidal activity of essential oils from mint and Ajwain against pulse beetle Callosobruchus chinensis (L). Indian J. Entomol.85, 229–233. 10.55446/IJE.2022.800 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takla, S. S., El-Dars, F. M., Amien, A. S. & Rizk, M. A. Prospects of neem essential oil as bio-pesticide and determination of its residues in eggplant plants during crop production cycle. Eg. Acad. J. Biol. Sci., F Toxicol. Pest Control10.21608/eajbsf.2021.181340 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oppert, B. et al. Genes related to mitochondrial functions are differentially expressed in phosphine-resistant and -susceptible Tribolium castaneum. BMC Genomics.16, 968. 10.1186/s12864-015-2121-0 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan, Y. X. et al. Acute lethal and sublethal effects of four insecticides on the lacewing (Chrysoperla sinica Tjeder). Chemosphere.250, 126321. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126321 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ningombam, A. et al. Strategies and management practices for stored grain pest 133–145 (An Option for Climate Smart Agriculture & Natural Resource Management, Integrated Farming System for Sustainable Hill Agriculture, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onstad, D. W., & Knolhoff, L. M. Major issues in insect resistance management. In Insect resistance management. Academic Press pp1-29 (2023). 10.1016/B978-0-12-823787-8.00008-8

- 16.Du, B., Chen, R., Guo, J. & He, G. Current understanding of the genomic, genetic, and molecular control of insect resistance in rice. Mol. Breed.40, 1–25. 10.1007/s11032-020-1103-3 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naqqash, M. N., Gökçe, A., Bakhsh, A. & Salim, M. Insecticide resistance and its molecular basis in urban insect pests. Parasitol. Res.115, 1363–1373. 10.1007/s00436-015-4898-9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han, J. B., Li, G. Q., Wan, P. J., Zhu, T. T. & Meng, Q. W. Identification of glutathione S-transferase genes in Leptinotarsa decemlineata and their expression patterns under stress of three insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol.133, 26–34. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.03.008 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kortbeek, R. W., van der Gragt, M. & Bleeker, P. M. Endogenous plant metabolites against insects. Eur. J. Plant Pathol.154, 67–90. 10.1007/s10658-018-1540-6 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu, K. et al. Characterization of heat shock protein 70 transcript from Nilaparvata lugens (Stål): Its response to temperature and insecticide stresses. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol.10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.01.011 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou, C. et al. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the development, reproduction, and susceptibility of the white-backed planthopper, sogatella furcifera (hemiptera: Delphacidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol.20(3), 996–1000. 10.1016/j.aspen.2017.07.002 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi, W. et al. Characterization and expression profiling of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes in the diamondback moth. Plutella xylostella L Bmc Genomics10.1186/s12864-016-3096-1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ru, Y., Chen, Y., Shang, S. & Zhang, X. Effects of sublethal dose of avermectin on the activities of detoxifying enzymes in Teranychus urticae. J. Gansu. Agric. Univ.52, 87–91 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feyereisen, R. Insect CYP genes and P450 enzymes. In Insect molecular biology and biochemistry Academic Press pp. 236-316 (2012). 10.1016/B978-0-12-384747-8.10008-X

- 25.Panini, M., Manicardi, G. C., Moores, G. D. & Mazzoni, E. An overview of the main pathways of metabolic resistance in insects. Invertebrate Surviv. J.10.25431/1824-307X/isj.v13i1.326-335 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu, F. et al. A brain-specific cytochrome P450 responsible for the majority of deltamethrin resistance in the QTC279 strain of Tribolium Castaneum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.107, 8557–8562. 10.1073/pnas.1000059107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raghavan, V., Kraft, L., Mesny, F. & Rigerte, L. A simple guide to de novo transcriptome assembly and annotation. Brief. Bioinform.10.1093/bib/bbab563 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sayadi, A., Immonen, E., Bayram, H. & Arnqvist, G. The de novo transcriptome and its functional annotation in the seed beetle Callosobruchus maculatus. PLoS One.11(7), e0158565. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158565 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolawole, A. O. & Kolawole, A. N. Insecticides and bio-insecticides modulate the glutathione-related antioxidant defense system of Cowpea storage Bruchid (Callosobruchus maculatus). Int. J. Insect Sci.10.4137/IJIS.S18029 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma, P., Pandya, P. & Parikh, P. Elucidating the host preference by the pulse Callosobruchus Chinensis (L). Indian J. Entomol.10.55446/IJE.2023.778 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma, P., Salunke, A., Pandya, N., Pandya, P. & Parikh, P. Transgenerational effects of sublethal deltamethrin exposure on development and repellency behaviour in Callosobruchus chinensis. J. Stored. Prod. Res.108, 102379. 10.1016/j.jspr.2024.102379 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinform.21(18), 3674–3676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol.215(3), 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic. Acids. Res.40(D1), D109–D114. 10.1093/nar/gkr988 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome. Biol.11(2), 1–12. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell, S. et al. eggNOG v3. 0: orthologous groups covering 1133 organisms at 41 different taxonomic ranges. Nucleic Acids. Res10.1093/nar/gkr1060 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hara, Y. et al. Optimizing and benchmarking de novo transcriptome sequencing: from library preparation to assembly evaluation. BMC Genomics.16(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12864-015-2007-1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.28(11), 1947–1951. 10.1002/pro.3715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zdobnov, E. M. & Apweiler, R. InterProScan–an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinform.17(9), 847–848. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods.25(4), 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karimzadeh, R., Salehpoor, M. & Saber, M. Initial efficacy of pyrethroids, inert dusts, their low-dose combinations and low temperature on Oryzaephilus surinamensis and Sitophilus granarius. J. Stored. Prod. Res.91, 101780. 10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101780 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ortega, D. S., Bacca, T., Silva, A. P. N., Canal, N. A. & Haddi, K. Control failure and insecticides resistance in populations of Rhyzopertha dominica (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) from Colombia. J. Stored Prod. Res.92, 101802. 10.1016/j.jspr.2021.101802 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shakoori, F. R., Riaz, T., Ramzan, U., Feroz, A. & Shakoori, A. R. Toxicological effect of esfenvalerate on carbohydrate metabolizing enzymes and macromolecules of a stored grain pest, Trogoderma granarium. Pak. J. Zool.50, 2185–2192. 10.17582/journal.pjz/2018.50.6.2185.2192 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liao, M. et al. Insecticidal activity of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil and RNA-Seq analysis of Sitophilus zeamais transcriptome in response to oil fumigation. PloS one10.1371/journal.pone.0167748 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma, M., Chang, M. M., Lu, Y., Lei, C. L., & Yang, F. L. Ultrastructure of sensilla of antennae and ovipositor of Sitotroga cerealella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), and location of female sex pheromone gland. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 40637. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40637 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Huang, Y. et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals differential gene expression of detoxification enzymes in Sitophilus zeamais responding to terpinen-4-ol fumigation. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol.149, 44–53. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2018.05.008 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lv, L. et al. Combined analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of wheat kernels reveals constitutive defense mechanism against maize weevils. Front. Plant. Sci.14, 1147145. 10.3389/fpls.2023.1147145 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao, Y. et al. Transcriptomic identification and characterization of genes responding to sublethal doses of three different insecticides in the western flower thrips. Frankliniella occidentalis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol.167, 104596. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104596 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng, X. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals global gene expression changes of Chilo suppressalis in response to sublethal dose of chlorantraniliprole. Chemosphere10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.129 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sagri, E. et al. Olive fly transcriptomics analysis implicates energy metabolism genes in spinosad resistance. BMC Genomics.15, 1–20. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-714 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonora, M. et al. ATP synthesis and storage. Purinergic. Signal.8, 343–357. 10.1007/s11302-012-9305-8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo, Y. et al. Cloning and different expression of ATP synthase genes between propargite resistant and susceptible strains of Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Acarina: Tetranychidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol.10.1016/j.aspen.2018.01.023 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng, F., Xiao, Y., Xie, L., Liu, Q. & Qian, K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of ABC transporter family member ABCG1 gene in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Channels.15(1), 375–385. 10.1080/19336950.2021.1909301 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.David, J. P. et al. Transcriptome response to pollutants and insecticides in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti using next-generation sequencing technology. BMC Genomics.11, 1–12. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-216 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilkins, R. M. Insecticide resistance and intracellular proteases. Pest Manag. Sci.73(12), 2403–2412. 10.1002/ps.4646 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang, L. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals gene expression changes of the fat body of silkworm Bombyx mori L in response to selenium treatment. Chemosphere10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125660 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang, L., Lu, M., Han, G., Du, Y. & Wang, J. Sublethal effects of chlorantraniliprole on development, reproduction and vitellogenin gene (CsVg) expression in the rice stem borer Chilo Suppressalis. Pest Manag. Sci.72(12), 2280–2286. 10.1002/ps.4271 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peng, J. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides novel insight into morphologic and metabolic changes in the fat body during silkworm metamorphosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19, 1–14. 10.3390/ijms19113525 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hotamisligil, G. S. & Davis, R. J. Cell signaling and stress responses. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Boil.8(10), a006072. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006072 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohan, C. Signal transduction. A short overview of its role in health and disease. EMD Chemicals, San Diego, California, USA. 183 (2009).

- 63.Mathangasinghe, Y., Fauvet, B., Jane, S. M., Goloubinoff, P. & Nillegoda, N. B. The Hsp70 chaperone system: Distinct roles in erythrocyte formation and maintenance. Haemax.106(6), 1519. 10.3324/haematol.2019.233056 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bavithra, C. M. L., Murugan, M., Pavithran, S. & Naveena, K. Enthralling genetic regulatory mechanisms meddling insecticide resistance development in insects: Role of transcriptional and post-transcriptional events. Front. Mol. Biosci.10, 1257859. 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1257859 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siddiqui, J. A. et al. Insights into insecticide-resistance mechanisms in invasive species: Challenges and control strategies. Front. Physiol.13, 1112278. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1112278 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalsi, M. & Palli, S. R. Cap n collar transcription factor regulates multiple genes coding for proteins involved in insecticide detoxification in the red flour beetle tribolium castaneum. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol.90, 43–52. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.09.009 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pan, Y., Zeng, X., Wen, S., Liu, X. & Shang, Q. Characterization of the Cap ‘n’Collar Isoform C gene in Spodoptera frugiperda and its association with superoxide dismutase. Insects.11(4), 221. 10.3390/insects11040221 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liang, X. et al. Insecticide-mediated up-regulation of cytochrome P450 genes in the red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum). Int. J. Mol. Sci.16(1), 2078–2098. 10.3390/ijms16012078 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park, J. C. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression of the entire 52 glutathione S-transferase (GST) subfamily genes in the Cu2+-exposed marine copepods Tigriopus japonicus and Paracyclopina nana. Aquat. Toxicol.209, 56–69. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.01.020 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dai, L. et al. Characterisation of GST genes from the Chinese white pine beetle Dendroctonus armandi (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and their response to host chemical defence. Pest. Manag. Sci.72(4), 816–827. 10.1002/ps.4059 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song, X. et al. Functional diversification of three delta-class glutathione S-transferases involved in development and detoxification in Tribolium castaneum. Insect Mol. Biol.29, 320–336. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1112278 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiong, C., Xia, Y., Zheng, P. & Wang, C. Increasing oxidative stress tolerance and subculturing stability of cordyceps militaris by overexpression of a glutathione peroxidase gene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.97, 2009–2015. 10.1007/s00253-012-4286-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piedrafita, G., Keller, M. A. & Ralser, M. The impact of non-enzymatic reactions and enzyme promiscuity on cellular metabolism during (oxidative) stress conditions. Biomol.5(3), 2101–2122. 10.3390/biom5032101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharmen, F. et al. A versatile functional food source Lasia spinosa leaf extract modulates the mRNA expression of a set of antioxidant genes and recovers the paracetamol-induced hepatic injury by normalizing the biochemical and histological markers. J. Funct. Foods.109, 105800. 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105800 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang, X., Sun, X., Xiang, Y., Li, H. & Li, Y. Effects of abamectin stress on the food chain of malus micromalus-aphis citricola-harmonia axyridis. Sci. Silvae. Sin.47, 172–177 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cao, Y. et al. Role of modified atmosphere in pest control and mechanism of its effect on insects. Front. Physiol.10, 206. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00206 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fu, J., Gao, J., Liang, Z. & Yang, D. PDI-regulated disulfide bond formation in protein folding and biomolecular assembly. Molecules26(1), 171. 10.3390/molecules26010171 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakamura, T. & Lipton, S. A. Redox modulation by S-nitrosylation contributes to protein misfolding, mitochondrial dynamics, and neuronal synaptic damage in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. Death. Differ.18(9), 1478–1486. 10.1038/cdd.2011.65 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository. Raw RNA-Seq data is deposited in FASTQ format to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1058855 and BioSamples accession number SAMN39190691 and SAMN39190692.