Abstract

Kaposi sarcoma is an undisputed malignancy associated with a heightened relative risk after transplantation. Similar to other causes of Kaposi's sarcoma, cutaneous involvement is typical in post-transplant patients; however, visceral involvement rarely occurs. We report a rare case of de novo hepatic Kaposi's sarcoma manifesting as an ill-defined infiltrative lesion in the left lobe of the liver in a patient who was immunosuppressed for 9 months after a kidney transplantation using ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and fluorodeoxyglucose-PET.

Keywords: Kaposi Sarcoma, Kidney Transplantation, Liver

Abstract

카포시 육종은 장기이식 후 발병의 상대위험도가 명백히 증가하는 악성 종양 중 하나이다. 다른 원인의 카포시 육종처럼 이식 후 환자에서 발생하는 카포시 육종도 피부 병변의 형태가 가장 흔하지만, 드물게 내장 기관 침범이 발생할 수 있다. 본 증례는 신장 이식 후 9개월간 면역 억제 치료를 받은 환자에서 발견된 간좌엽의 침윤성 병변이 카포시 육종으로 진단된 경우로서, 저자들은 신장 이식 환자에서 드물게 발생하는 간의 카포시 육종 사례를 초음파, CT, MRI 및 fluorodeoxyglucose-PET 영상 소견과 함께 보고하고자 한다.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage kidney disease, with an average of over 1000 registered kidney transplants in Korea annually from 2014 to 2019 and over 25000 in the United States in 2022 (1,2). Immunosuppressive therapies are mandatory to prevent graft loss, which, in turn, leads to side effects such as increased infection and cancer. Malignancy is the third most prevalent cause of mortality in individuals who have undergone kidney transplantation. Among the various types of cancers, Kaposi sarcomas, nonmelanoma skin cancers, and lymphomas show the most significant increase in incidence after kidney transplantation (3). Kaposi sarcoma often presents as cutaneous lesions in organ transplant recipients and patients with other causes; however, visceral involvement rarely occurs (4). Solitary liver involvement is rare, and to the best of our knowledge, no case reports of hepatic Kaposi sarcoma occurring solely in the liver without skin involvement have been reported in kidney transplant recipients. Here, we present a case of Kaposi sarcoma that manifested as a de novo hepatic malignancy in a patient who underwent kidney transplantation.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old male presented to the emergency room with high fever. He had undergone dead donor kidney transplantation for an end-stage kidney disease 9 months previously and had been on immunosuppression since then. He had undergone left nephroureterectomy and right hemicolectomy 7 years prior for papillary urothelial carcinoma and low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, respectively.

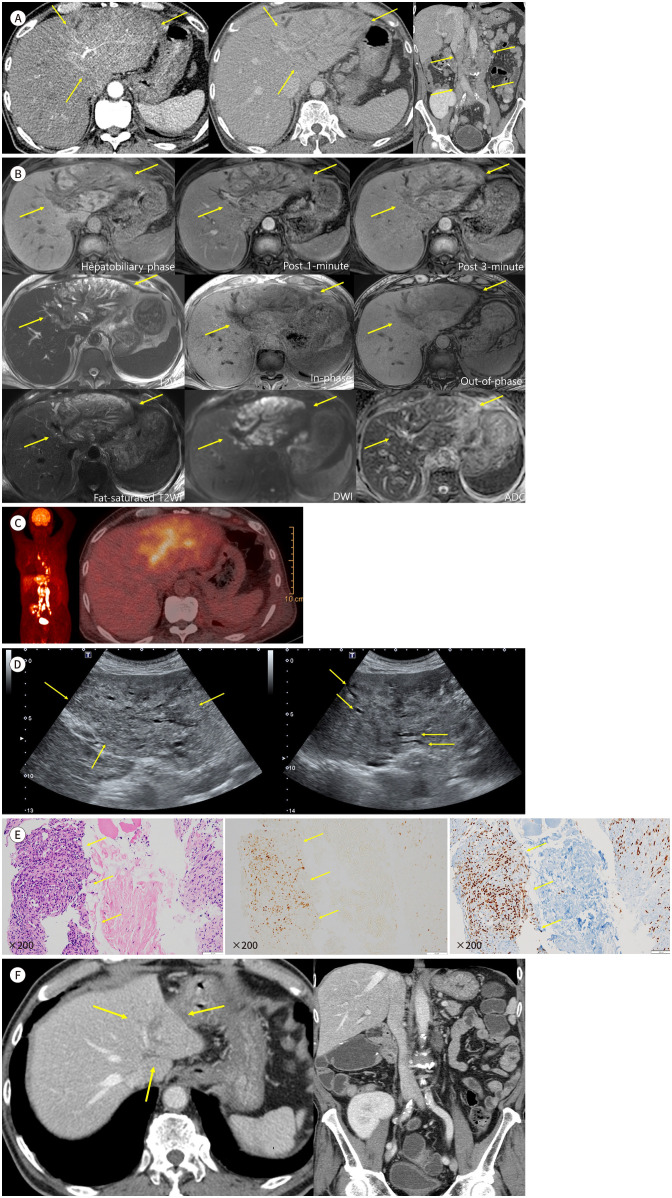

Initially, contrast-enhanced CT was performed to check for a hidden source of the intra-abdominal infection (Fig. 1A). CT incidentally revealed an ill-defined infiltrative lesion involving the entire left lobe of the liver, spreading along the portal triad. The lesion exhibited slight hyperenhancement in the arterial phase, hypoattenuation in the portal phase, and heterogeneous enhancement of the intervening hepatic parenchyma in the portal phase owing to congestive changes. Diffuse dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts in the left lobe of the liver was also observed. Marked enlargement with conglomeration of lymph nodes in the periportal, aortocaval, left para-aortic, and bilateral common iliac areas was observed.

Fig. 1. Hepatic Kaposi sarcoma in a 65-year-old male after a kidney transplant.

A. CT images show contour bulging of the left lobe and ill-defined slight hyperenhancement along segment III artery in the arterial phase (left, arrows) and hypoattenuation in portal phase with congestive changes of intervening hepatic parenchyma (middle, arrows). Marked enlargement with conglomeration of lymph nodes in periportal, aortocaval, left para-aortic, and bilateral common iliac areas are noted (right, arrows).

B. MR images best show the extent of disease in the hepatobiliary phase, appearing hypointense compared to normal parenchyma, along segment III portal vein (P3) and its branches (first row left, arrows). Left duct obliteration by the mass and dilatation of segment II intrahepatic duct (B2) and segment III intrahepatic duct (B3) ducts are noted on T2-weighted images (second row left and third row left, arrows). The lesion shows poor enhancement compared to normal parenchyma in post 1-min and 3-min images with congestive changes of intervening hepatic parenchyma (first row middle and right, arrows). The lesion does not show signal drop on inphase and out-of-phase images (second row middle and right, arrows) and shows diffusion restriction (third row middle and right, arrows).

C. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET showing an ill-defined hypermetabolic mass in the left lobe of the liver and multiple hypermetabolic retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

D. Ultrasound images show diffuse hypoechoic infiltrative lesion along segment III portal triad (left, arrows) and peripheral intrahepatic duct dilatations (right, arrows).

E. Histopathological specimens show vascular and spindle cell proliferative lesion (hematoxylin & eosin stain, left, arrows). Immunohistochemistry staining reveals Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus patch positive (middle, arrows) and ERG positive (right, arrows).

F. After modification of immunosuppressant at the time of diagnosis, markedly decreased extent of primary lesion (arrows) and retroperitoneal lymph nodes are noted, with volume shrinkage of left lobe of the liver.

ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient, DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, ERG = ETS-related gene, T2WI = T2-weighted imaging

Liver protocol MRI using a hepatobiliary-specific contrast agent revealed the extent of the infiltrative mass in the left hepatic lobe (Fig. 1B), which was best visualized during the hepatobiliary phase. It appeared hypointense compared with the normal parenchyma, predominantly along segment III of the portal vein and its branches. The mass obliterated the left bile duct, and dilatation of segments II and III intrahepatic ducts was noted on T2-weighted images. The lesion showed poor enhancement compared to that of the normal parenchyma in post 1- and 3-min contrast-enhanced images, with congestive changes in the intervening hepatic parenchyma. Additionally, the lesion showed diffusion restriction and no signal drop in in-phase and out-of-phase images. We initially considered unusual metastasis from a known urothelial carcinoma or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, with lymph node metastasis as a differential diagnosis.

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET revealed an ill-defined hypermetabolic mass in the left lobe of the liver and multiple hypermetabolic retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Fig. 1C). Ultrasonography (USG) for a percutaneous liver biopsy revealed a diffuse infiltrative mass in the left lobe of the liver. The lesion was relatively hypoechoic compared to the normal hepatic parenchyma. Peripheral intrahepatic duct dilatation, observed on CT and MRI, was also observed on USG (Fig. 1D).

Histopathological examination of specimens revealed vascular and proliferative spindle cell lesions. Immunohistochemical staining revealed Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV) patch positivity, ETS-related gene (ERG) positivity (Fig. 1E), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) negativity, and smooth muscle antibody (SMA) negativity, consistent with a diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma.

The immunosuppressive regimen was adjusted according to the diagnosis. Without any other measures, the size of the primary lesion and retroperitoneal lymph nodes decreased markedly, with volume shrinkage in the left lobe of the liver (Fig. 1F). The radiological scope of the disease was stable for >11 months until the most recent follow-up. The patient did not exhibit any relevant symptoms.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution, and the requirement for informed consent was waived (IRB No. 30-2024-4).

DISCUSSION

Increased malignancy due to immunosuppression has been reported after kidney transplantations. However, Kaposi sarcoma is an undebated malignancy with an increased relative risk after transplantation (3). In our case, the patient had undergone a kidney transplant and had been immunosuppressed for approximately 9 months before being diagnosed.

Kaposi sarcoma is an endothelial cell cancer caused by KSHV infection with a highly heterogeneous histopathology and clinical behavior. Skin is typically involved in patients undergoing solid-organ transplantation; however, visceral involvement is rare. Biopsy results showing immunohistochemical positivity for KSHV confirmed this diagnosis (4).

The imaging findings of post-transplant hepatic Kaposi sarcoma have not been established; however, some literature on the imaging findings of acquired immunodeficiency virus-related hepatic Kaposi sarcoma can be found (5,6). These articles indicated findings of hepatomegaly with nodular or band-like lesions along peripheral branches of portal veins on ultrasound; hypodense nodules in the hilar, periportal, or capsular areas with delayed enhancement on CT; isointense areas in T2-weighted images; and hypointense nodules in the hepatobiliary phase on MRI.

In the present case, contour bulging was observed in the left lobe. The lesions were hypoechoic on USG, hypodense on precontrast CT images (not shown), and predominantly at the periportal location. These results are consistent with previously documented findings. However, the following findings have not been previously documented. The lesions were not nodular or linear in shape but were infiltrative and ill-defined in all modalities. They showed slight hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and hypoenhancement from the portal to the delayed phase. The lesions showed T2 hyperintensity, T1 hypointensity, and diffusion restriction on MRI. Peripheral intrahepatic duct dilatation and retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement were also observed.

Based on these findings, the first possible differential diagnosis was intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (IHCC), particularly with periductal infiltration, with or without a combined mass-forming type. The periductal-infiltrating type typically shows diffuse periductal thickening with increased enhancement and an abnormally dilated or irregularly narrowed duct. The mass-forming type commonly displays irregular peripheral and gradual centripetal enhancements (7). We differentiated Kaposi sarcoma from IHCC because bile duct wall thickening or enhancement was not prominent in this case. The second possible differential diagnosis was post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). PTLD can involve solid organs in the form of solitary, scattered, or infiltrative pattern with T1 hypointensity. In PTLD with solid-organ involvement, lesions typically show poor enhancement (8). Hence, differentiating between Kaposi sarcoma and PTLD was challenging because of their overlapping imaging features. Clinical findings, such as cutaneous involvement, may be helpful for differentiation. The third possible differential diagnosis is infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), considering the slight hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and adjacent lymph node enlargement. Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC) also must be differentiated, considering adjacent bile duct dilatation with the aforementioned findings. Infiltrative HCC was known to be frequently associated with portal vein tumor thrombosis (9). However, in the present case, portal vein tumor thrombosis was not observed, although the lesions were diffusely distributed periportally. The imaging features of cHCC-CC are the characteristic coexistence of imaging findings of HCCs and IHCC. Furthermore, IHCC features are more frequently observed than HCC features in cHCC-CC cases (61.4% and 54.1% of cases, respectively) and are associated with a larger tumor size (>2 cm) (10). In our case, however, characteristic IHCC features, such as gradual arterial hyperenhancement or bile duct wall thickening, were not definite despite the relatively larger tumor extent covering the entire left lateral segment of the liver. Elevation of α-fetoprotein levels can suggest the presence of HCC, and coelevation or discordant elevation of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and α-fetoprotein levels with presumptive imaging findings can indicate cHCC-CC (10). Unfortunately, serum tumor markers were not examined in our study.

In general, the regression of post-transplant Kaposi sarcoma can be achieved by reducing, discontinuing, or modifying immunosuppressants. In cases that do not respond to these treatments, combination chemotherapy may be initiated (4). In the present case, the immunosuppressants were modified at the time of diagnosis. The radiological extent of the disease gradually decreased to a stable state and the patient did not have any associated clinical abnormalities.

In this report, we present the imaging findings and clinical course of de novo hepatic Kaposi sarcoma in a kidney transplant recipient. Although rare, Kaposi sarcoma should be considered when encountering such hepatic involvement, considering the heightened relative risk in patients with kidney transplants.

Footnotes

- Conceptualization, all authors.

- investigation, R.S., L.M.S.

- methodology, R.S., L.M.S.

- project administration, L.M.S.

- resources, R.S., L.M.S.

- supervision, L.M.S.

- writing—original draft, R.S.

- writing—review & editing, all authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: None

References

- 1.Jeon HJ, Koo TY, Ju MK, Chae DW, Choi SJN, Kim MS, et al. The Korean Organ Transplantation Registry (KOTRY): an overview and summary of the kidney-transplant cohort. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2022;41:492–507. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.21.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 2022 organ transplants again set annual records; organ donation from deceased donors continues 12-year record-setting trend. 2023. [Accessed January 27, 2024]. Available at. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/2022-organ-transplants-again-set-annual-records-organ-donation-from-deceased-donors-continues-12-year-record-setting-trend .

- 3.Ietto G, Gritti M, Pettinato G, Carcano G, Gasperina DD. Tumors after kidney transplantation: a population study. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:18. doi: 10.1186/s12957-023-02892-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Restrepo CS, Martínez S, Lemos JA, Carrillo JA, Lemos DF, Ojeda P, et al. Imaging manifestations of Kaposisarcoma. Radiographics. 2006;26:1169–1185. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Addula D, Das CJ, Kundra V. Imaging of Kaposi sarcoma. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:5297–5306. doi: 10.1007/s00261-021-03205-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung YE, Kim MJ, Park YN, Choi JY, Pyo JY, Kim YC, et al. Varying appearances of cholangiocarcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:683–700. doi: 10.1148/rg.293085729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borhani AA, Hosseinzadeh K, Almusa O, Furlan A, Nalesnik M. Imaging of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder after solid organ transplantation. Radiographics. 2009;29:981–1000. doi: 10.1148/rg.294095020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds AR, Furlan A, Fetzer DT, Sasatomi E, Borhani AA, Heller MT, et al. Infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: what radiologists need to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:371–386. doi: 10.1148/rg.352140114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim TH, Kim H, Joo I, Lee JM. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: changes in the 2019 World Health Organization histological classification system and potential impact on imaging-based diagnosis. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:1115–1125. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]