Abstract

Purpose:

Hydroxyapatite (HA) scaffolds are common replacement materials used in the clinical management of critical-sized bone defects. This study was undertaken to examine the potential benefits of fluoridated derivatives of hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite (FA), and fluorohydroxyapatite (FHA) as bone scaffolds in conjunction with adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs). If FHA and FA surfaces could drive the differentiation of stem cells to an osteogenic phenotype, the combination of these ceramic scaffolds with ADSCs could produce materials with mechanical strength and remodeling potential comparable to autologous bone. This study was designed to investigate the ability of the apatite surfaces HA, FA, and FHA produced at different sintering temperatures to drive ADSCs toward osteogenic lineages.

Methods:

HA, FHA, and FA surfaces sintered at 1150 °C and 1250 °C were seeded with ADSCs and evaluated for cell growth and gene and protein expression of osteogenic markers at 2 and 10 days post-seeding.

Results:

In vitro, ADSC cells were viable on all surfaces; however, differentiation of these cells into osteoblastic lineage only observed in apatite surfaces. ADSCs seeded on FA and FHA expressed genes and proteins related to osteogenic differentiation markers to a greater extent by Day 2 when compared to HA and cell culture controls. By day 10, HA, FA, and FHA all expressed more bone differentiation markers compared to cell culture controls.

Conclusion:

FA and FHA apatite scaffolds may promote the differentiation of ADSCs at an earlier time point than HA surfaces. Combining apatite scaffolds with ADSCs has the potential to improve bone regeneration following bone injury.

Keywords: Bone scaffold, Adipose derived stem cells, Hydroxyapatite, Fluoridated hydroxyapatite, Differentiation

1. Introduction

Infection, tumor resection, and high energy trauma are some of the common clinical circumstances that can result in significant bony defects. Skeletal trauma leads to approximately 500,000 bone grafting procedures performed each year in the USA (Fernandez de Grado et al., 2018; Greenwald et al., 2001). Autograft bone replacement is the “Gold Standard” and provides the best clinical outcomes since autograft bone is immunologically identified as “self” and is osteoconductive (bone cells attach and move on surface), osteoinductive (the material itself or factors released from the material promotes bone growth and stem cell differentiation), and osteogenic (material provides cells that produce bone). Autograft bone offers structural support, a matrix for bone cell adhesion and growth, and stimulates and recruits stem cells that can differentiate into bone-forming cells (Goldberg and Stevenson, 1987; Hasan et al., 2018; Oryan et al., 2014). However, the use of autograft bone has significant consequences to injured patients. In addition to the limited quantity of bone available for autograft harvest, obtaining this graft bone increases operative time and the number of surgical sites and introduces postoperative donor site pain (Hasan et al., 2018; Oryan et al., 2014). Alternative bone replacement materials available to trauma surgeons are decellularized allograft bone and engineered bone substitutes. Allografts—decellularized cadaveric bone—can be supplied in much larger volumes than autograft bone, and this material is available in varying shapes and sizes (Buser et al., 2016; Giannoudis et al., 2005; Hasan et al., 2018). Allografts, like autografts, are osteoconductive and osteoinductive but they do not provide the native “self” cellular support present in autografts. Since clinical outcomes using either autograft or allograft materials still remain sub-optimal, bone replacement research has increasingly focused on engineered bone substitutes (Fernandez de Grado et al., 2018; Greenwald et al., 2001).

An ideal engineered bone substitute should replicate the beneficial qualities of autograft bone that include structural support, a reliable source of osteogenic cells, and the capacity to generate osteogenic signals (Goldberg and Stevenson, 1987; Hasan et al., 2018; Oryan et al., 2014). One biomaterial that has been used clinically as a structural and biological bone graft substitute is synthetic hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] (HA). The HA scaffold has the advantage of possessing the chemical and structural properties of the mineral component of native bone tissue making it biocompatible (Buser et al., 2016; Hasan et al., 2018). Derivatives of HA have also been investigated as potential bone substitutes, which include the fluorohydroxyapatites [Ca10(PO4)6Fy(OH)2-y] (FHA) and fluorapatites [Ca10(PO4)6F2] (FA). These fluoridated hydroxyapatites are similar to HA but have enhanced properties in terms of biocompatibility, strength, in vivo stability and cell adhesion (Bennett et al., 2019; Hahn et al., 2013; Nasker et al., 2019). All three of these apatites have been investigated as potential coatings for orthopedic implants and as bone graft substitutes (Bennett et al., 2019; Hahn et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2005). Several reports have indicated that the sintering temperatures used during the process of manufacturing apatite-based bone substitutes have a profound effect upon their porosity, mechanical strength, topographical features, surface charge, and cell adhesion and differentiation properties (Bennett et al., 2019; Nasker et al., 2019). In addition to these temperature related improvements in material strengths, the in vivo remodeling properties of these apatite-based bone scaffolds may be much improved by the introduction of growth factors and/or stem cells (Abboud et al., 2003; Hasan et al., 2018; Lobb et al., 2019; Sohn and Oh, 2019).

Various stem cells have the capacity to differentiate into various cellular lineages and are highly sensitive to extracellular surfaces, mechanical stimuli, and presence or absence of growth factors. While their mechanobiology, surface chemistry, topography, and pore size are somewhat passive characteristics, HA scaffolds have also been shown to actively direct the differentiation of mesenchymal embryonic and adipose cells into an osteoblast lineage (Dai et al., 2016; Ghasemi-Mobarakeh et al., 2015). Adipose tissue is an excellent source of stem cells and is an abundant and easily accessed tissue. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) can differentiate into an osteogenic lineage in response to biomechanical and biochemical cues. Moreover, calcium phosphate ceramics are used clinically as biomaterials for bone regeneration because of their ability to induce osteoblastic differentiation in progenitor cells (Muller et al., 2005, 2008; Samavedi et al., 2013). Thus, the overall goal of this study was to investigate, in vitro, how material compositions (HA, FA, FHA) and sintering temperatures impact the viability of ADSCs and their differentiation into an osteoblast lineage.

2. Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Also, all chemicals were used as received unless specified.

2.2. Apatite synthesis and test disk fabrication

HA, FA, and FHA powder synthesis and the test disk fabrication procedures were previously described in detail (Bennett et al., 2019). Briefly, FHA and FA were synthesized by mixing 250 ml of 1.2 M Ca (NO3)2 solution and 250 ml of 0.72 M Na2HPO4 solution containing various stoichiometric ratios of NaF. Post-synthesis, apatites were characterized by their fluoride, phosphate, and calcium contents. The crystallinity of the apatites was determined using X-ray diffraction techniques. The purity of the apatites was confirmed using infrared spectrophotometry.

To determine the cellular adhesion and differentiation characteristics of the apatite surfaces, small disks were prepared from the raw powder. Briefly, 65 μL of sterile water was added to 300 mg of HA, FHA or FA powders and mixed thoroughly using a mortar and pestle. This dense slurry was transferred to a 10 mm diameter die and compacted under vacuum using a manual hydraulic press, and finally, sintered at pre-selected temperatures using a box furnace (Muffle Box Furnace; Sentrotech, Strongsville, OH). The sintering cycle was comprised of a 2-h isothermal hold at pre-selected temperatures of 1150 and 1250 °C with a heating/cooling rate of 7 °C/min. After sintering, all disks were cleaned with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and steam sterilized. Post-sintering, a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) was used to confirm the micro-scaled topographical features of the surface. Surface properties of the apatites were fully described in our previously published manuscript (Bennett et al., 2019).

2.3. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell culture

The ADSCs (RASMD-01001, Santa Clara, CA) were maintained in growth media (GUXMD-900011; Cyagen, Santa Clara, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. All experiments were conducted with cells between passage 3–5.

2.4. Cell viability

ADSCs were plated on a cell culture plate (cell drop control; Costar TC Treated, Corning Inc., Corning, NY), HA disk sintered at 1150 or 1250 °C, FA disk sintered at 1150 °C or 1250 °C, or FHA disk sintered at 1150 or 1250 °C at a density of 13,600 cells/cm2 for the analysis of cell viability at day 2 post seeding and 1,300 cells/cm2 for analysis at day 10 post seeding (n = 4 disks/group). We plated different densities of cells for Day 2 and Day 10 to increase the number of cells available for analysis at Day 2 and overcrowding at day 10. Otherwise, all assays were conducted using the same conditions. Following incubation for the pre-set time points, cell viability was evaluated using an alamarBlue® assay (Invitrogen, Carisbad, CA). ADSCs were exposed to a 10% alamarBlue® solution for 2 h at 37 °C, and then fluorescence read (FLx800, BioTek, Winooski, VT) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All data are reported as viability relative to cell drop control.

2.5. RT-PCR

ADSCs were plated on the aforementioned surfaces at the same densities and duration as described in the cell viability study (n = 4 disks/group). After the incubation periods, cells were removed from the surfaces with trypsin (2.5% trypsin; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), and total RNA was extracted (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA quality and quantity were evaluated (2200 TapeStation, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and then reverse transcribed (TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). Gene expression was then quantified using real-time PCR (QuantStudio 12K Flex; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) with gene-specific primers for runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2; RN01512298_m1; NM_001278483.1) and Osteopontin (SPP1; RN00681031_m1, Thermo Fisher ID; NM_012881.2, NCBI Reference Sequence). All values were normalized to the housekeeping gene 18s ribosomal RNA (Hs999999901_s1; X03205.1, GenBank) and data reported as 2^ΔΔct and calculated relative to the cell drop control.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

ADSCs seeded on surfaces for 2 or 10 days were fixed in 10% formalin and then incubated with primary antibody for osteocalcin (1:400, ab13420; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or osteopontin (1:400, ab8448; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The samples were then incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies for osteocalcin (ab175472; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and osteopontin (A31573; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). Samples were imaged on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope at 10x magnification.

2.7. ADSC statistics

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Group differences in ADSC viability and gene expression were evaluated by ANOVA, followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test (JMP, SAS Institute). Significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Scaffold surface structure

Based on our previous study, we chose 1150 and 1250 °C apatite surfaces for this study (Bennett et al., 2019). This is because while HA and FHA sintered at 1150 °C increased cellular differentiation, FA disks sintered at both 1150 and 1250 °C, showed enhanced cellular differentiation. This temperature range was also chosen, in part, due to the reported densification temperature range of apatite surfaces. Interestingly, the SEM photo micrographs of sintered apatites (Fig. 1) further demonstrated the presence of micro topographical features. It is also important to note that, while FA sintered at 1250 °C maintained its micro topographical features, HA and FHA sintered at 1250 °C, are beginning to lose these features (Fig. 1). This is especially true for the HA sintered at 1250 °C, which appeared to have a smoother surface compared to the disks sintered at 1150 °C.

Fig. 1.

A representative set of SEM images showing topographical features of HA, FHA, and FA sintered at both 1150 °C and 1250 °C. The respective lower magnification (x500) image is shown as an inset image at the upper left hand corner of each higher magnification (x5000) image. The individual grains are more clearly visible in the samples sintered at 1150 °C compared to those sintered at 1250 °C. Within the 1250 °C sintered samples, the HA has a smoother texture compared to the FHA and FA.

3.2. Cell viability

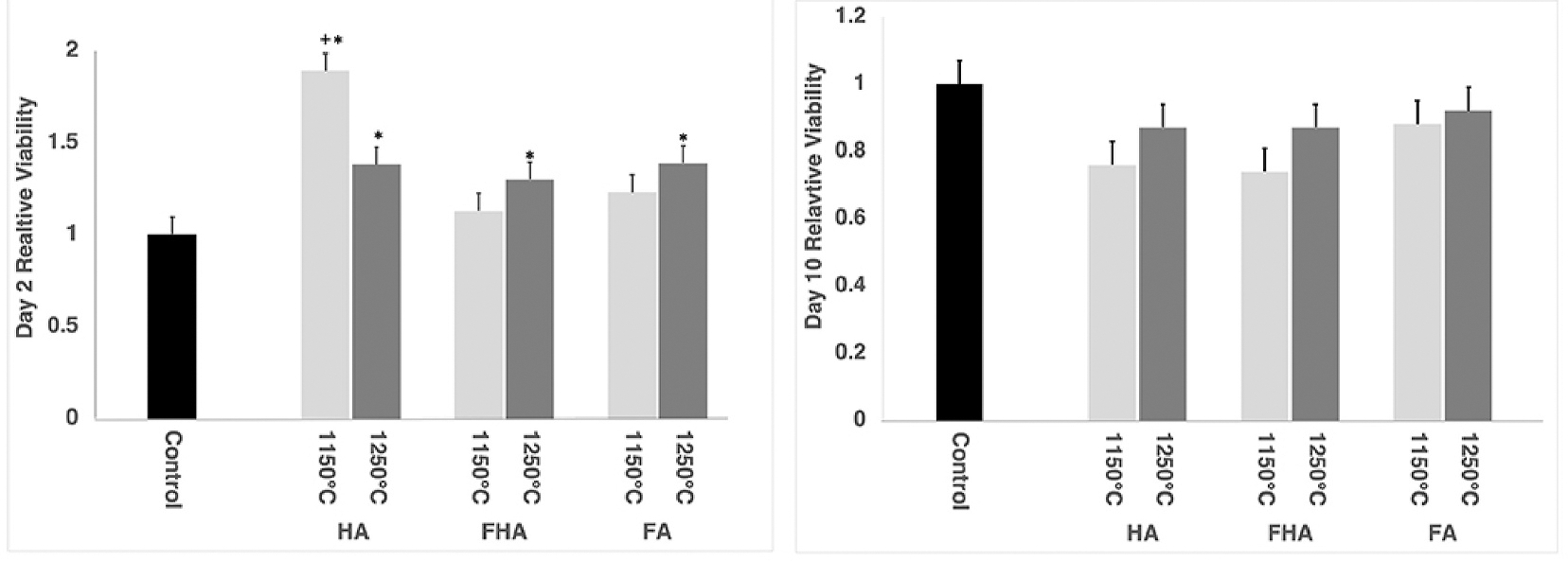

At two days post-seeding, there were more viable cells on the HA1150 °C surface (1.9 ± 0.09) compared to all other groups, suggesting ADSCs either preferentially proliferated or selectively adhered to a greater extent on this surface (Fig. 2, p<0.05). Additionally, the cell drop control group (1 ± 0.09) had statistically fewer viable cells than the HA (1.4 ± 0.09), FA (1.4 ± 0.09), FHA (1.3 ± 0.09) apatite disks sintered at 1250 °C. By 10 days post-seeding, there were no statistical differences between the cell drop control group and the different apatite surfaces (p>0.05).

Fig. 2.

Bar-charts showing the cell viability at 2 days post-seeding (Left) and at 10 days post-seeding (Right). All groups, with the exception of FA1150 °C and FHA1150 °C, had significantly more viable cells than the control group after 2 days. + statistically different from all other groups; * statistically different from cell drop control.

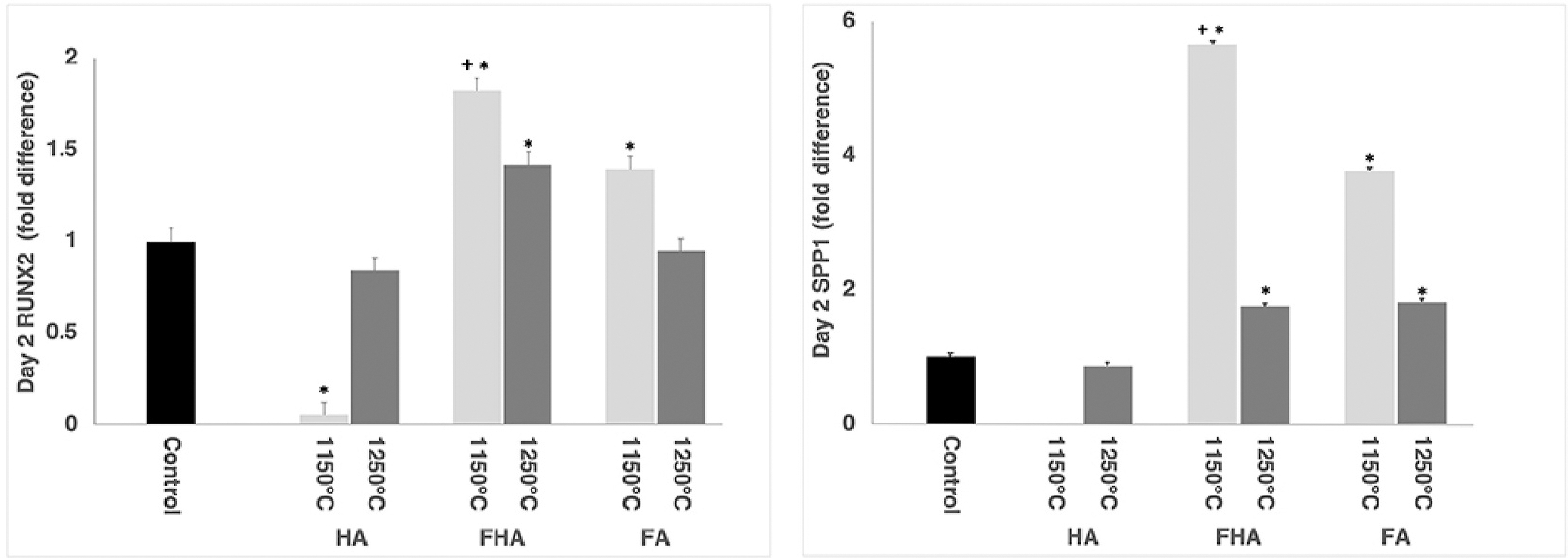

3.3. RT-PCR day 2

All 2^ΔΔct data, fold difference, is reported relative to cell drop control. RUNX2, a transcription factor associated with the early differentiation of stem cells into pre-osteoblast cell lineage, was expressed at lower levels in ADSCs plated on HA1150 °C (0.06 ± 0.07; p<0.01) and at equivalent levels to the cell drop control on HA1250 °C (0.9 ± 0.07; p = 0.18; Fig. 3). These data are supported by the expression of SPP1, a marker of later stage osteoblast differentiation, which was undetectable in cells plated on HA1150 °C and equivalent when compared to the cell drop control plated on HA1250 °C (0.9 ± 0.05; p =0.05). Together these data suggest that at two days post seeding HA1150 °C and HA1250 °C did not promote extensive differentiation of the ADSC into bone cells to a greater degree than cells plated onto a cell culture dish (cell drop control).

Fig. 3.

Day 2 RT-PCR data for (Left) Runx2 and (Right) SPP1. On average the osteoblast markers Runx2 and SPP1 were expressed in the ADSC cell plated on FA and FHA to a greater degree than those plated on the cell drop control surface. * statistically different than cell drop control; + statistically different from all other groups, p<0.05.

In contrast with the HA groups, there was greater expression of the early osteoblast differentiation marker RUNX2 in cells that were grown on FA1150 °C (4.1 ± 0.07) and FHA 1150 °C (5.7 ± 0.07) surfaces when compared to the cell drop control (p<0.05). There was significantly more RUNX2 expression in cells seeded on the FHA1250 °C group (1.4 ± 0.07). However, there was no difference noted in the expression of RUNX2 between ADSCs seeded on FA1250 °C (0.95 ± 0.07; p = 0.18) and the cell drop control.

The levels of expression of SPP1 mRNA, another marker of osteoblast differentiation, were elevated when ADSCs were seeded onto FA1150 °C (4.1 ± 0.05), FA1250 °C (1.8 ± 0.05), FHA 1150 °C (5.7 ± 0.05), and FHA 1250 °C (1.8 ± 0.05) and were statistically different (p<0.01) than the cell drop control. By day 2, ADSCs seeded on both FA and FHA surfaces appeared to differentiate into an osteogenic lineage to a greater extent than did those on HA surfaces at this time point. This was illustrated by the greater expressions of Runx2 and SPP1. Additionally, ADSCs growing on FHA 1150 °C expressed greater levels of RUNX2 and SPP1 compared to all other groups tested (p<0.05). Interestingly, both RUNX2 and SPP1 expressions in FHA and FA sintered at 1150 °C were greater than the same samples sintered at 1250 °C, indicating an effect of the sintering temperature on stem cell differentiation (p<0.05).

3.4. RT-PCR day 10

When compared to the cell drop control (1.0 ± 0.2 and 1.0 ± 0.9), cells plated onto the 1150 °C surfaces, HA1150 °C (3.1 ± 0.2 and 13.4 ± 0.9), FA1150 °C (4.3 ± 0.2 and 18.6 ± 0.9) and FHA1150 °C (2.0 ± 0.2 and 5.0 ± 0.9) expressed significantly greater levels of RUNX2 and SPP1, respectively (Fig. 4). Thus, all three surfaces sintered at 1150 °C expressed the bone differentiation markers RUNX2 and SPP1 to a greater extent than ASCSs on the cell drop control group. More interestingly, FA1150 °C expressed ~18-fold greater expression of SPP1, a later stage osteogenic differentiation marker. Within the 1250 °C groups, only the cells plated on the FA1250 °C disks expressed both SPP1 (5.8 ± 0.9) and Runx2 (2.5 ± 0.2) at higher levels than the cell drop control (p<0.05). HA1250 °C and FHA1250 °C had greater expression of Runx2 (2.5 ± 0.2; 1.6 ± 0.2; respectively p<0.05) and equivalent expression of SPP1 (3.9 ± 0.9; 3.6 ± 0.9 respectively p>0.05).

Fig. 4.

Day 10 RT-PCR data for (Left) RUNX2 and (Right) SPP1. On average ADSCs plated on the three apatite surfaces (HA, FHA, and FA) expressed the osteoblast differentiation markers (RUNX2 and SPP1) to a greater extent than ADSCs plated on a cell culture plate. *statistically different than cell drop control, p<0.05. + statistically different from all other groups, p<0.05.

3.5. Immunohistochemistry

On day 2, the apatite surfaces had greater osteopontin and osteocalcin staining compared to the cell culture control, as there was little staining for either protein within the control group (Fig. 5). Within the samples sintered at 1150 °C, each apatite looked like they had similar expression levels of both osteopontin and osteocalcin, suggesting all surfaces were able to promote ADSC differentiation into bone-forming cells. While within the 1250 °C, the FHA and FA samples had greater protein expression of both markers compared to the HA samples. Similar relationships existed when examined on Day 10 (Fig. 6). That is, there was very little staining for either bone marker on the cell control samples compared to the HA, FHA, and FA samples. The combined PCR and immunohistochemistry data suggest that ADSCs transformed into an osteoblast lineage at an earlier time when they were seeded onto FA and FHA surfaces than when they were seeded onto HA surfaces.

Fig. 5.

Osteoblast markers expressed at two days -post-seeding: ADSCs growing on FA and FHA 1150 °C (left) and 1250 °C (right) appeared to have a greater expression of the osteoblast markers osteopontin (OPN) and osteocalcin (OCN), when compared to the expression of the same markers when ADSC’s were grown on HA and cell drop control. Additionally, there is more staining on the 1150 °C surfaces than the 1250 °C surfaces.

Fig. 6.

ADSCs seeded on the different 1150 °C (left) and 1250 °C (right) apatite surfaces for ten days express the proteins osteopontin (OPN translated by the mRNA of the gene SSP1)) and osteocalcin (OCN).

4. Discussion

The development of an ideal engineered bone substitute requires replicating, or improving upon, the material and biological properties of allograft bone i.e. strong structural support, a reliable source of osteogenic cells, and the capacity to generate osteogenic signals (Goldberg and Stevenson, 1987; Hasan et al., 2018; Oryan et al., 2014). We investigated, in vitro, the effects of changes in hydroxyapatite scaffold compositions and sintering temperatures on the viability of ADSCs and their ability to differentiate into an osteoblast lineage. All three apatite surfaces, HA, FHA, and FA, sintered at either 1150 °C and 1250 °C supported cell adhesion and viability. In terms of differentiation into an osteogenic lineage, ADSCs growing on FHA and FA surfaces on day 2, exhibited significantly greater expression of the early and late osteoblast differentiation genes RUNX2 and SPP1, respectively, when compared to ADSCs growing on HA and cell culture plate controls. FA surfaces sintered at 1150 °C resulted in an over 18-fold expression of the SSP1 gene at 10-days compared to the control and greater expression the of SSP1 gene than all other groups. These gene expression data were also supported by data showing the presence of the mineral-binding matrix proteins osteopontin (encoded by the SSP1 gene) and osteocalcin, with earlier expression when ADSCs were plated onto the fluoridated surfaces compared to HA and control surface. These findings of ADSC viability and early differentiation into an osteogenic lineage support the use of FA and FHA surfaces as an engineered bone scaffold.

The differentiation of ADSC’s toward an osteoblastic lineage when seeded on apatite surfaces, especially the early osteoblastic differentiation on fluoridated surfaces, suggests a potential to improve bone ingrowth on scaffolds when both ADSCs and fluoridated surfaces are used in combination. It is well-known that the surface properties of scaffolds can impact cell adhesion and viability (Dhivya et al., 2018; Hesaraki et al., 2014; Olivares-Navarrete et al., 2015). Initially, ADSCs did preferentially adhere to and were more viable on the apatite surfaces when compared to the cell drop control. When comparing the different apatites, at Day 2, there was higher cell viability on the HA 1150 °C when compared to the other apatite surfaces. However, by ten days post plating, there were no differences in ADSC viability between the HA, FA, and FHA surfaces. Although cells adhered to and grew on the HA surfaces preferentially, these cells did not have increased expression of differentiation markers when compared to those seeded on FA and FHA surfaces by Day 2. ADSCs growing on FA and FHA surfaces had enhanced mRNA and protein expression of multiple osteoblast markers compared to the same cells growing on HA surfaces 2 days post-seeding.

Literature inform us that not all cell lineages behave in the same manner when plated on different apatite surfaces. Keratinocytes preferentially adhere to and grow on FA surfaces when compared to HA and FHA (Bennett et al., 2019). Additionally, embryonic stem cells preferentially grow on fluorine substituted HA rather than HA (Harrison et al., 2004) while fibroblasts and osteoblasts adhere to and proliferate at equivalent levels on HA, FA, and FHA surfaces (Bennett et al., 2019), (Kim et al., 2005). As far as we can determine, this study is the first to assess and compare the capacity of ADSC’s to adhere to and remain viable on differing HA, FHA, and FA surfaces. While there were more viable cells on the HA 1150 °C surface two days post seeding when compared to the other apatite surfaces, by 10 days there were no group differences. This seems to indicate that ADSCs, like fibroblasts and osteoblasts, adhere to and are viable on HA and fluoridated HA surfaces to a similar extent.

Sintering temperatures influence the surface structural characteristics of apatites i.e. grain size, surface charge, porosity, and surface area (Bennett et al., 2019; Mealy and O’Kelly, 2015; Wang et al., 2017). We have previously published similar findings of increases in grain size, decreases in porosity, and increases in surface charge when HA, FA, and FHA are sintered between 1150 °C to 1250 °C compared to non-sintered or the same materials sintered at a lower temperature, 1050 °C. It was found that the sintering temperature had a greater impact on surface topography than fluoridation. When sintered above their densification temperature of ~1000 °C (Patel et al., 2001) and below the phase change temperature ~1350 °C (Liao et al., 1999) apatite surfaces begin to transform with micro topographical features. Such micro features are known to be conducive for improving surface-induced cellular adhesions and activities (Harrison et al., 2004; Hesaraki et al., 2014; Kobayashi et al., 2019; Mealy and O’Kelly, 2015). We observed slight differences in cell adhesion when ADSC grew on 1150 °C versus 1250 °C sintered surfaces. For FHA and FA surfaces, ADSC had approximately 10% more viable cells when grown on the 1250 °C versus 1150 °C sintered surfaces. This relationship held up when cells were grown on HA surfaces for ten days, but after two days, there were more viable cells on the HA 1150 °C surfaces compared to the 1250 °C sintered surfaces. It should be noted that cell numbers, as the results of cellular proliferation, may not have a direct relationship to cellular differentiation. The lack of any dramatic differences in cell viability, relative to the sintering temperatures, may be because the temperatures (1150 °C and 1250 °C) used to manufacture these scaffolds were quite high. We have previously shown that fibroblasts and keratinocytes preferentially adhere to and grow on HA, FA, and FHA surfaces sintered at 1150 °C and 1250 °C when compared to the same materials sintered at 1050 °C; with no differences seen between the two higher temperatures (Bennett et al., 2019). These findings are supported by those of other groups who have also shown that sintering at higher temperatures promotes the adhesion and growth of fibroblasts and osteoblasts on HA when using a sintering temperature near 1200 °C when compared to a sintering temperature near 800 °C (Kobayashi et al., 2019). In our study, sintering temperature appeared to impact differentiation of ADSC into an osteogenic lineage as well as adhesion and viability.

There are numerous approaches to promoting the differentiation of stem cells into a bone lineage; these include the use of growth factors and varying the surface chemistries and topography (Dhivya et al., 2018; Ghasemi-Mobarakeh et al., 2015; Mealy and O’Kelly, 2015). While growth factors, such as bone morphogenic protein (BMP), have been shown to promote bone growth at injury sites, and the differentiation of stem cells into a bone lineage, they have the disadvantage that their bioavailability decreases over time and they have a short half-life (Blandizzi et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2015; Yang and Hinner, 2015). These limitations are overcome by using the physical structure of the scaffold surface to promote the adhesion and differentiation of stem cells. For example, stem cells preferentially differentiate into a bone lineage on rougher surfaces when compared to smooth surfaces (Olivar-es-Navarrete et al., 2010). Similarly, osteoblasts also mature to a greater extent on rougher surfaces (Zhao et al., 2007). As noted previously, sintering temperature indeed profoundly impacted the surface topographical micro-features, with the 1150 °C surfaces having a slightly more porous structure and micro roughness. We also observed that within the fluoridated groups, there was a greater expression of both RUNX2 and SPP1 in the 1150 °C sintered groups compared to the 1250 °C sintered groups: indicating a greater cellular differentiation possibly owning to these micro-features. This was especially true for the SPP1 expression level at both 2 and 10 days, post-seeding. For HA, expression levels of RUNX 2 and SPP1 were low at two days, but by ten days, there was a similar relationship of greater expression in ADSC cells grown on 1150 °C surfaces compared to 1250 °C surfaces. Sintering temperature also impacted protein expression, with the 1250 °C samples having greater expression compared to the 1150 °C samples. It appears that the large differences in osteopontin and osteocalcin were found between the different apatite samples within the same sintering temperature at Day 10. The clear expression of the bone markers osteopontin and osteocalcin on the apatite surfaces compared to the control surface suggested that ADSC can indeed differentiate into bone-forming cells when grown on these sintered apatites.

Importantly, it is worth mentioning that as the stem cells differentiate, they initially become pre-osteoblasts, then mature osteoblasts, and finally to osteocytes. The relative expression levels of RUNX-2, osteopontin, and osteocalcin are based on their degree of differentiation. For example, while RUNX-2 is expressed by pre-osteoblasts, mature osteoblasts express both osteopontin and osteocalcin (Asserson et al., 2019; Komori, 2019; Qi et al., 2003). However, when these cells are completely differentiated into osteocytes, only osteopontin is expressed by them. As the major intention of this study was to show that the fluoridated apatite surfaces direct the ADSC to osteoblastic lineage, by confirming the presence of bone markers present, we have successfully demonstrated this concept. However, further studies are needed to delineate the importance and mechanistic differences in the differentiation of ADSC between the different apatites and sintering temperatures.

Although the quantification of expression levels of bone biomarkers is beyond the scope of this study, it is still worth mentioning the trend. In terms of RUNX2 expression, both FA and FHA at either sintering temperature had greater expression at Day 2 than control or HA. By Day 10, all three surfaces had increased RUNX2 expression levels compared to cell drop controls. However, the HA and FA groups appeared to increase expression of RUNX2 between Day 2 to Day 10. At the same time, FHA levels remained elevated but did not increase over the same time frame. Other research investigating the differentiation of stem cells into a bone lineage in vitro has observed steadily increasing levels of RUNX2 over a three-week time span (Calabrese et al., 2016; Lv et al., 2020). In terms of SPP1, the fluoridated surfaces, FHA and FA, had greater expression of SPP1 at Day 2 compared to HA, and this was supported by the immunohistochemical assay for the protein osteopontin. By day 10, there were pronounced increases in SPP1 gene expression in the HA 1150 °C and FA 1150 °C samples compared to the other scaffolds. Although all scaffolds appeared to express greater levels of SPP1, they did not all have further increase between Day 2 and Day 10. Most studies appear to show initial increases and then a plateauing at elevated levels (Calabrese et al., 2016; Hesaraki et al., 2014; Lv et al., 2020). However, the time point of leveling ranges from less than a week to more than two weeks. Thus, FHA may support early differentiation but maintained levels over time. In contrast, the FA surfaces appear to extend the length of time of increased signaling. The protein expression data for all three surfaces showed increased expression of both osteopontin—which is coded by the SPP1 gene—and osteocalcin over time, further supporting that all three surfaces support differentiation of ADSC into a bone lineage, with the fluoridated surfaces inducing this process at an earlier time point. Other investigators have also shown that combining implant materials with apatite promotes the differentiation of stem cells, including ADSC’s, into a bone lineage (Dhivya et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2012; Saxer et al., 2016). We also observed that ADSC’s expressed bone lineage markers on the apatite surfaces and the timing of expression was dependent upon the type of apatite. ADSCs plated onto FA and FHA scaffolds expressed bone lineage markers, as evaluated by mRNA and protein expression, to a greater extent at 2 days post-seeding than cells seeded onto HA or cell drop controls. Fluorine is known to promote the proliferation and differentiation of bone-forming cells, so the earlier differentiation of ADSCs when plated on FA and FHA surfaces is in accordance with the literature (Bennett et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015; Mealy and O’Kelly, 2015). Most research has focused on the relationship of surface properties on the differentiation of embryonic and bone marrow derived mesenchymal cells, with less focus on ADSC. As mentioned, ADSC’s are clinically abundant and readily accessible while possessing the ability to differentiate into an osteogenic lineage. They are also the major source of stem cells in the stormal vascular fraction (SVF)—FDA-approved cells for therapeutic use. As mentioned, this is the first investigation that examines the impact of different formulations of apatite surfaces, with and without fluorine, on ADSC adhesion, viability, and differentiation. The early differentiation of ADSC’s, on FA and FHA surfaces could potentially improve the rate and quality of bone formation in the clinical setting. Future investigations will be needed to determine if these advantages obtain in an in vivo setting.

There are several limitations to this investigation. Firstly, we plated cells at a higher density at Day 2 compared to Day 10, so cells didn’t progress under the same conditions. However, groups within the same time point were plated in the same manner, so differences between the apatite surface types are still valid and independent of these plating differences. Additionally, previous stem cell studies have shown similar changes in growth, decreasing with time as stem cells differentiate, RUNX2 expression increasing with time over the first two weeks, and SPP1 increasing early and then plateauing (Calabrese et al., 2016; Hesaraki et al., 2014; Lv et al., 2020). This is similar to the data that we observed suggesting that plating at different densities had a limited impact on the overall progression of the stem cell differentiation to a bone-forming cell lineage. Other limitations include only a limited number of bone differentiation markers and time points included in this reported study. Future research will expand time series, and include further differentiation markers in vitro. Also, in vivo studies will be conducted to demonstrate the potential of these biomaterials to improve bone growth after injury.

In general, to be an effective bone scaffold/substitute, bone replacement materials should provide mechanical support, a surface to which bone-forming cells preferentially adhere, and provide biochemical cues/signals that induce the differentiation of cells to regenerate bone matrix(Goldberg and Stevenson, 1987; Hasan et al., 2018; Oryan et al., 2014). Finally, they should support matrix remodeling into viable bone tissue without introducing an added secondary immune response. Since FA and FHA surfaces were successful in inducing differentiation of the ADSCs to an osteoblastic lineage within 2-days, the combination of SVF and fluoridated apatite scaffolds have the potential to replace autografts and allografts in the clinical setting. This concept is currently being evaluated in a translational animal study.

5. Conclusion

Surface characteristics such as chemical composition and texture can impact cell adhesion, viability, and differentiation. ADSCs were viable on all apatite surfaces examined in the present study. ADSCs expressed bone differentiation markers, as measured by gene and protein expression, earlier when plated on fluoridated apatite scaffolds, FH and FHA, when compared to those plated on HA and a cell culture plate. By day 10, ADSCs plated on all apatite surfaces showed a greater expression of bone lineage markers compared to the control group. The proposed stem cell-scaffold combination approach will provide not only the mechanical support, but also, the autologous cells and osteogenic signals for effective bone tissue regeneration—all necessary requirements for bone regeneration in the clinical setting of bone loss. Future research will investigate the in-vivo potential of the combination of fluoridated apatite scaffolds and ADSCs, to promote more rapid and higher quality bone healing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of VA RR&D (RX003328-01A1) “Heat-treated porous fluorapatite scaffolds with adipose derived stem cells for bone regeneration” and the Univeristy of Utah Cell Imaging and Genomics Core facilites.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Sujee Jeyapalina, has patent Fluorapatite Coated Implants and Related Methods pending to University of Utah. Jeyapalina S, Agarwal J, Beck JP, and Shea, J has patent Fluorapatite-Containing Structures pending to University of Utah.

Author statement

Authors will make all data available upon request.

Availability of data and material

All data will be made available if requested.

References

- Abboud SL, Ghosh-Choudhury N, Liu C, Shen V, Woodruff K, 2003. Osteoblast-specific targeting of soluble colony-stimulating factor-1 increases cortical bone thickness in mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1386–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asserson DB, Orbay H, Sahar DE, 2019. Review of the pathways involved in the osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. J. Craniofac. Surg. 30, 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BT, Beck JP, Papangkorn K, Colombo JS, Bachus KN, Agarwal J, Shieh JF, Jeyapalina S, 2019. Characterization and evaluation of fluoridated apatites for the development of infection-free percutaneous devices. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 100, 665–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandizzi C, Meroni PL, Lapadula G, 2017. Comparing originator biologics and biosimilars: a review of the relevant issues. Clin. Therapeut. 39, 1026–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser Z, Brodke DS, Youssef JA, Meisel HJ, Myhre SL, Hashimoto R, Park JB, Yoon ST, Wang JC, 2016. Synthetic bone graft versus autograft or allograft for spinal fusion: a systematic review. J. Neurosurg. Spine 25, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese G, Giuffrida R, Fabbi C, Figallo E, Lo Furno D, Gulino R, Colarossi C, Fullone F, Giuffrida R, Parenti R, Memeo L, Forte S, 2016. Collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffolds induce human adipose derived stem cells osteogenic differentiation in vitro. PLoS One 11, e0151181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai R, Wang Z, Samanipour R, Koo KI, Kim K, 2016. Adipose-derived stem cells for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Stem Cell. Int. 2016, 6737345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhivya S, Keshav Narayan A, Logith Kumar R, Viji Chandran S, Vairamani M, Selvamurugan N, 2018. Proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on scaffolds containing chitosan, calcium polyphosphate and pigeonite for bone tissue engineering. Cell Prolif 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez de Grado G, Keller L, Idoux-Gillet Y, Wagner Q, Musset AM, Benkirane-Jessel N, Bornert F, Offner D, 2018. Bone substitutes: a review of their characteristics, clinical use, and perspectives for large bone defects management. J. Tissue Eng. 9, 2041731418776819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Prabhakaran MP, Tian L, Shamirzaei-Jeshvaghani E, Dehghani L, Ramakrishna S, 2015. Structural properties of scaffolds: crucial parameters towards stem cells differentiation. World J. Stem Cell. 7, 728–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E, 2005. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury 36 (Suppl. 3), S20–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg VM, Stevenson S, 1987. Natural history of autografts and allografts. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AS, Boden SD, Goldberg VM, Khan Y, Laurencin CT, Rosier RN, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Committee on Biological I, 2001. Bone-graft substitutes: facts, fictions, and applications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A (Suppl. 2 Pt 2), 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn BD, Cho YL, Park DS, Choi JJ, Ryu J, Kim JW, Ahn CW, Park C, Kim HE, Kim SG, 2013. Effect of fluorine addition on the biological performance of hydroxyapatite coatings on Ti by aerosol deposition. J. Biomater. Appl. 27, 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J, Melville AJ, Forsythe JS, Muddle BC, Trounson AO, Gross KA, Mollard R, 2004. Sintered hydroxyfluorapatites–IV: the effect of fluoride substitutions upon colonisation of hydroxyapatites by mouse embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials 25, 4977–4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A, Byambaa B, Morshed M, Cheikh MI, Shakoor RA, Mustafy T, Marei H, 2018. Advances in osteobiologic materials for bone substitutes. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 12 (6), 1448–1468. 10.1002/term.2677. Epub 2018 May 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesaraki S, Nazarian H, Pourbaghi-Masouleh M, Borhan S, 2014. Comparative study of mesenchymal stem cells osteogenic differentiation on low-temperature biomineralized nanocrystalline carbonated hydroxyapatite and sintered hydroxyapatite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 102, 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HW, Lee EJ, Kim HE, Salih V, Knowles JC, 2005. Effect of fluoridation of hydroxyapatite in hydroxyapatite-polycaprolactone composites on osteoblast activity. Biomaterials 26, 4395–4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Nihonmatsu S, Okawara T, Onuki H, Sakagami H, Nakajima H, Takeishi H, Shimada J, 2019. Adhesion and proliferation of osteoblastic cells on hydroxyapatite-dispersed Ti-based composite plate. In: Vivo, vol. 33, pp. 1067–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, 2019. Regulation of proliferation, differentiation and functions of osteoblasts by Runx2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Huang B, Mai S, Wu X, Zhang H, Qiao W, Luo X, Chen Z, 2015. Effects of fluoridation of porcine hydroxyapatite on osteoblastic activity of human MG63 cells. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 035006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CJ, Lin FH, Chen KS, Sun JS, 1999. Thermal decomposition and reconstruction of hydroxyapatite in air atmosphere. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 35, 99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang X, Jin Q, Jin T, Chang S, Zhang Z, Czajka-Jakubowska A, Giannobile WV, Nor JE, Clarkson BH, 2012. The stimulation of adipose-derived stem cell differentiation and mineralization by ordered rod-like fluorapatite coatings. Biomaterials 33, 5036–5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb DC, DeGeorge BR Jr., Chhabra AB, 2019. Bone graft substitutes: current concepts and future expectations. J Hand Surg Am 44, 497–505 e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Roohani-Esfahani SI, Li J, Zreiqat H, 2015. Synergistic effect of nanomaterials and BMP-2 signalling in inducing osteogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Nanomedicine 11, 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H, Yang H, Wang Y, 2020. Effects of miR-103 by negatively regulating SATB2 on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One 15, e0232695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealy J, O’Kelly K, 2015. Cell response to hydroxyapatite surface topography modulated by sintering temperature. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 103, 3533–3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Bulnheim U, Diener A, Luthen F, Nebe B, Klinkenberg K, Neumann H, Liebold A, Stamm C, Rychly J, 2005. Calcium phosphate surfaces promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20. S368–S368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Bulnheim U, Diener A, Luthen F, Teller M, Klinkenberg ED, Neumann HG, Nebe B, Liebold A, Steinhoff G, Rychly J, 2008. Calcium phosphate surfaces promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 12, 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasker P, Samanta A, Rudra S, Sinha A, Mukhopadhyay AK, Das M, 2019. Effect of fluorine substitution on sintering behaviour, mechanical and bioactivity of hydroxyapatite. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 95, 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Haithcock DA, Cundiff CA, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD, 2015. Coordinated regulation of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation on microstructured titanium surfaces by endogenous bone morphogenetic proteins. Bone 73, 208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Hutton DL, Erdman CP, Wieland M, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z, 2010. Direct and indirect effects of microstructured titanium substrates on the induction of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards the osteoblast lineage. Biomaterials 31, 2728–2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oryan A, Alidadi S, Moshiri A, Maffulli N, 2014. Bone regenerative medicine: classic options, novel strategies, and future directions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 9, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N, Gibson IR, Ke S, Best SM, Bonfield W, 2001. Calcining influence on the powder properties of hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 12, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H, Aguiar DJ, Williams SM, La Pean A, Pan W, Verfaillie CM, 2003. Identification of genes responsible for osteoblast differentiation from human mesodermal progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 3305–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavedi S, Whittington AR, Goldstein AS, 2013. Calcium phosphate ceramics in bone tissue engineering: a review of properties and their influence on cell behavior. Acta Biomater. 9, 8037–8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxer F, Scherberich A, Todorov A, Studer P, Miot S, Schreiner S, Guven S, Tchang LA, Haug M, Heberer M, Schaefer DJ, Rikli D, Martin I, Jakob M, 2016. Implantation of stromal vascular fraction progenitors at bone fracture sites: from a rat model to a first-in-man study. Stem Cell. 34, 2956–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn HS, Oh JK, 2019. Review of bone graft and bone substitutes with an emphasis on fracture surgeries. Biomater. Res. 23, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Ma Y, Wei J, Chen X, Cao L, Weng W, Li Q, Guo H, Su J, 2017. Effects of sintering temperature on surface morphology/microstructure, in vitro degradability, mineralization and osteoblast response to magnesium phosphate as biomedical material. Sci. Rep. 7, 823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang NJ, Hinner MJ, 2015. Getting across the cell membrane: an overview for small molecules, peptides, and proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 1266, 29–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Raines AL, Wieland M, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD, 2007. Requirement for both micron- and submicron scale structure for synergistic responses of osteoblasts to substrate surface energy and topography. Biomaterials 28, 2821–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data will be made available if requested.