Abstract

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) poses a global health challenge, particularly in its advanced stages known as critical limb ischemia (CLI). Conventional treatments often fail to achieve satisfactory outcomes. Patients with CLI face high rates of morbidity and mortality, underscoring the urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies. Recent advancements in biomaterials and biotechnology have positioned biomaterial-based vascularization strategies as promising approaches to improve blood perfusion and ameliorate ischemic conditions in affected tissues. These materials have shown potential to enhance therapeutic outcomes while mitigating toxicity concerns. This work summarizes the current status of PAD and highlights emerging biomaterial-based strategies for its treatment, focusing on functional genes, cells, proteins, and metal ions, as well as their delivery and controlled release systems. Additionally, the limitations associated with these approaches are discussed. This review provides a framework for designing therapeutic biomaterials and offers insights into their potential for clinical translation, contributing to the advancement of PAD treatments.

Graphical Abstract

Overview of biomaterial-based vascularization strategies for enhanced treatment of PAD. By Figdraw

Keywords: Peripheral arterial diseases, Vascularization, Biomaterials, Biotechnology, Bioactive drug delivery

Introduction

PAD has garnered increasing attention in recent years due to its high prevalence and mortality rates [1, 2]. Specifically, in its advanced stage, known as CLI, patients suffer from excruciating pain and face significant mortality risks [3]. A study reports that only 27.1% of CLI patients survive without amputation after five years [4]. Furthermore, data reveal an all-cause mortality rate of 57% within five years following CLI, emphasizing its severity [5]. Conventional treatments, including pharmacotherapy, vascular surgery and amputations, are commonly inadequate in fully treating CLI and carry risks of adverse effects [6]. Therefore, current research is primarily focused on developing innovative therapeutic strategies for more effective CLI management.

Recent advances in vascularization therapies have highlighted their potential to address the limitations of conventional treatments for CLI [7]. Current strategies include gene-based approaches to regulate angiogenic factors, cell-based therapies leveraging the regenerative potential of stem cells, and the delivery of bioactive proteins, peptides, and metal ions to stimulate vascular repair [8]. These approaches aim to improve blood flow, support tissue regeneration, and mitigate ischemia-induced damage. However, challenges such as targeted delivery, sustained bioactivity, and controlled therapeutic release remain critical obstacles, emphasizing the need for further innovation to enhance their clinical effectiveness.

Biomaterials offer promising solutions to these issues. Non-viral gene carriers, such as cationic polymers, liposomes, and peptides, provide safer alternatives to viral vectors [9]. Modifying gene carriers with targeting ligands, including peptides, antibodies, or carbohydrates, enhances cellular targeting, while polymer- or peptide-modified carriers facilitate endo/lysosomal escape and nuclear uptake [10]. Moreover, nanocarriers, bioengineered scaffolds, and hydrogels have been utilized to improve the bioactivity of proteins, peptides, and metal ions while enabling controlled release, thereby enhancing both the efficacy and safety of vascularization therapies [11].

In summary, this review provides an overview of PAD, examines the mechanisms, therapeutic roles of biomaterials in gene-, cell-, protein/peptide-, and metal ion-based vascularization strategies, and discusses future directions in this field.

Presentation and pathogenesis

PAD represents a severe ischemic condition with high morbidity and mortality, posing a significant threat to global health [12, 13]. By 2019, PAD affected approximately 113 million individuals aged ≥ 40, representing 1.52% of the global population [14]. PAD is primarily characterized by the narrowing or obstruction of blood flow in major systemic arteries, predominantly affecting the lower extremities [15]. In its early stages, PAD is often asymptomatic, but as the it progresses to CLI, symptoms like rest pain, ulcers, and gangrene in the lower limbs become prevalent [16]. Notably, patients with CLI face a 1-year mortality rate of 25-35% and an amputation rate of up to 30% [17]. These alarming statistics underscore the critical need for a deeper understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying PAD.

In CLI, plaque-induced narrowing reduces arterial blood flow, potentially leading to complete occlusion [18]. Over time, this chronic ischemia alters the microvascular system’s physiological environment, thereby exacerbating tissues damage. The hypoxia microenvironment stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in endothelial cells (ECs) primarily through the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). VEGF, upon binding to its receptor VEGFR (mainly VEGFR-2), activates downstream signaling cascades, including Ras/Raf/ERK pathways [19]. Meanwhile, hypoxia can promote epidermal growth factor (EGF) expression, activate ERK5 to interact with nuclear factors [20]. These combined processes regulate cell proliferation and migration, ultimately promoting spontaneous vascularization. However, the vascular system’s self-regulatory capacity is impaired during CLI, making tissues vulnerable to the effects of reduced blood perfusion [21]. Inadequate compensation leads to pathological changes in the muscles below the blockage, including atrophy, fibrosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction [22]. Collectively, these alterations contribute to the functional decline observed in many patients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathological mechanisms and effects of PAD. Created in https://BioRender.com

Recent research has emphasized the role of disease-related microenvironment in the development and progression of CLI [23, 24]. Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory condition, involves elevated levels of inflammatory markers and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can worsen CLI [25]. Additionally, the chronic ischemic environment also damages vascular ECs, leading to excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and causing EC dysfunction. This impairs the vascular endothelial layer’s ability to regulate permeability, tone, maintain hemodynamics, nitric oxide (NO) release, and resist platelet adhesion, all of which exacerbate CLI [26].

Conventional treatments

Conventional treatments of PAD and CLI primarily involves pharmacotherapy, vascular surgery, and amputation [27]. Pharmacotherapy includes antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, glucose-lowering agents, antihypertensives, lipid-lowering drugs, and β-blockers etc. These medications mainly target risk factors associated with CLI, such as thrombosis, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, rather than reversing or curing the ischemic condition. However, pharmacotherapy carries potential side effects, particularly on the cardiovascular system and liver, with a risk of bleeding [28].

Vascular surgeries include open procedures, such as bypass and endarterectomy, as well as endovascular techniques like balloon angioplasty and stenting. These approaches aim to restore arterial blood flow to the legs and feet, preventing further deterioration of CLI, improving patient mobility. While their effectiveness is validated, these procedures carry some risks, including potential endothelial damage and high morbidity rates at the donor site [29].

If pharmacotherapy and vascular surgery are unsuitable or ineffective, amputation remains a clinical option. Amputations are classified as minor or major, depending on the extent and location of the ischemic limb. However, this drastic measure profoundly impacts on patients psychologically and physically, leading to depression, anxiety, reduced mobility, and a diminished quality of life, all of which hinder their independence and recovery [30].

Emerging therapeutic vascularization strategies in PAD treatment

Endogenous processes including angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, and vasculogenesis contribute to tissue repair, but they often fall short in CLI [31]. This limitation suggests the necessity for developing therapeutic interventions to augment these natural reparative mechanisms. Currently, various genes, cells, proteins, peptides, and metal ions are being explored to activate vascularization activities in ECs. Each approach targets vascularization through distinct mechanisms, such as upregulating pro-angiogenic factors, leveraging cells to facilitate vascular regeneration, or modifying the ischemic microenvironment.

Despite their potentials, these strategies face challenges, including targeting ischemic tissues precisely, maintaining long-term efficacy, and controlling the release of bioactive molecules. Biomaterials have emerged as promising solution to address these obstacles, offering platforms that enhance the stability, bioactivity, and targeting precision of therapeutic agents [32]. In the following sections, the review will provide a detailed examination of these vascularization strategies, with a focus on the role of biomaterials in their applications, as well as discussing potential future developments in this field.

Biomaterial-based gene delivery systems for vascularization

The vascularization process in ECs is predominantly regulated by several key genes. To enhance vascularization in ischemic tissues, researchers have investigated various proangiogenic genes and developed advanced gene delivery system, which have shown efficacy in promoting vascular regeneration [33–37]. For instance, literature has demonstrated that nano-delivery of ZNF580 gene to ECs can enhance vascularization [38]. Other studies have reported the proangiogenic potential of delivering VEGF and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene to stimulate vascularization [39–44].

However, the direct application of naked genes is inherently inefficient and faces challenges, including degradation by nucleases, low cellular uptake, and lack of tissue specificity. These limitations have hindered the broader application of gene-based vascularization strategies, necessitating the use of biomaterials to address these obstacles and facilitate the development of effective gene delivery systems.

Gene delivery process

The success of gene therapy depends on the efficient delivery of therapeutic genes to target cells. For non-viral vectors, this gene delivery encompasses several critical steps: gene loading, cellular uptake, endo/lysosomal escape, and nuclear entry (Fig. 2). Each step is pivotal for gene to be successfully replicated, transcribed and translated within target cells, ultimately enabling its biological functions [45]. To enhance the efficacy of gene therapy, gene vectors need to be optimized to improve gene loading capacity, enhance cellular uptake, and facilitate both endo/lysosomal escape and nuclear entry.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of gene delivery process. By Figdraw

Gene vectors

To address the challenges associated with gene delivery, researchers have developed viral and non-viral gene vectors. Viral vectors, such as adenoviruses and Sendai viruses, are renowned for their high gene delivery efficiency, leveraging natural infection pathways to deliver genes directly into cell nucleus. However, the safety profile of viral vectors remains suboptimal [46]. For instance, adenoviral vectors have been linked to oncogenic risks, and high doses have been reported to induce liver and neurological damage in animal models [47].

In recent years, non-viral gene vectors have emerged as safer alternatives, with cationic polymers, liposomes, and peptides being the most prominent examples [48–51]. Compared to viral vectors, non-viral vectors offer several advantages, including low immunogenicity, higher safety, greater gene capacity, improved stability, and flexible chemical design, making them more suitable for clinical applications [52]. However, the non-viral vectors typically exhibit relatively lower gene delivery efficiency. This has driven ongoing research into the design and development of high-performance non-viral gene delivery materials.

Gene loading

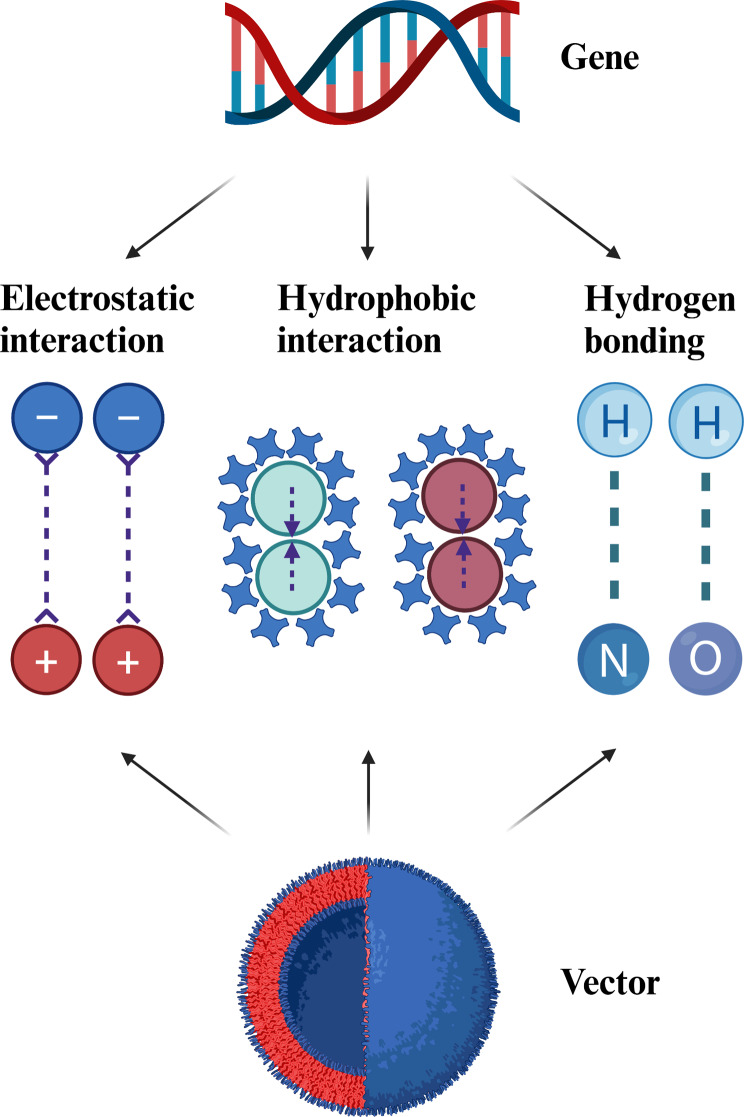

Efficient gene loading is essential for the success of gene vectors, as it relies on the interactions between gene vectors and gene themselves. Genes, composed of nucleotide monomers, exhibit unique physical properties including double-helical structure, external negative charges, hydrophilicity, internal hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [53]. To optimize gene binding and loading, researchers have designed gene vectors based on electrostatic interaction, hydrophobic interaction, and hydrogen bonding (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic illustration of the various interactions (electrostatic interaction, hydrophobic interaction, and hydrogen bonding). Created in https://BioRender.com

Electrostatic interactions are critical for gene loading. Positively charged polymers, liposomes and peptides are commonly used to compress and load genes via electrostatic attraction, forming stable gene complexes [54–65]. Representative materials include polymers such as poly-L-lysine (PLL), polyethyleneimine (PEI), and polyamidoamine (PAMAM); liposomes such as lipofectamine 2000 and 3000; and peptides such as cell penetrating peptides and nuclear localization sequence peptides. Additionally, recent developments have also explored the use of cationic polymers based on thiourea salts, which exhibit strong gene-loading capabilities [66].

Studies have shown that factors such as charge density, composition, the number of the head and tail groups, hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity, the linking group, and the shape (rod-shaped or spherical) all play a role in gene transfection [67]. Generally, higher positive charge densities on vectors enhance gene loading and transfection efficiency, but they can also induce toxicity and limit the applications of such vectors. To address this challenge, researchers employed innovative designs that incorporate multiple interactions into a single gene vector, including electrostatic, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonding. These strategies aid in stabilizing gene complexes, improving transfection efficiency and reducing toxicity. For example, the PAMAM dendrimers are chemically modified with diamino triazine groups containing both hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, allowing for combined electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bond that facilitate efficient gene loading [68]. Similarly, PLL polymers are modified with p-toluenesulfonyl-protected arginine to synergistically load genes via electrostatic, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bond [69].

Cellular uptake

Cellular uptake is a critical determinant of gene delivery efficiency. However, research on cellular uptake has encountered two fundamental challenges: how to increase the efficiency of gene uptake by cells and how to enhance the targeting specificity of gene toward cells. Initial strategies focused on optimizing the mixing ratios of positively charged vectors and negatively charged genes to control the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of gene complexes [70]. However, this method has shown limited efficacy.

Subsequently, researchers have turned their attention to the functionalization of gene vectors. For instance, hydrophobic modifications of PEI polymer with alkyl chains and aromatic groups enhance interactions between gene complexes and cell membranes, thereby increasing uptake efficiency [71–73]. Fluorinated modifications of PAMAM dendrimers and PEI polymers impart both hydrophobic and lipophobic characteristics to gene complexes, ultimately improving their stability during cellular uptake [74–78].

Guanidine modification is another common strategy to promote cellular uptake. Polymers containing guanidine groups not only establish electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged cell membrane, but also form the bidentate hydrogen bonds with phosphates, carboxylates, and sulfates on the membrane surface, which collectively enhance uptake efficiency [79–83].

Cell-penetrating peptides, such as transcriptional activator (TAT) peptide and octa-arginine (R8), also exhibit strong membrane-penetrating capabilities, making them become valuable tools for gene vector design. For example, Feng’s group modified a PLGA-PEI polymer with TAT peptide, enhancing gene uptake in ECs [84]. Also, introducing TAT and Arg-Glu-Asp-Val (REDV) peptides into polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane yields a star-shaped gene vector that achieves high uptake efficiency in ECs [85]. TAT peptide is frequently used to modify other materials, including β-cyclodextrin, phospholipids (e.g. DSPE), mesoporous silica nanoparticles, and gold nanoparticles, thereby improving gene uptake efficiency across various cell lines [86–91].

Unfortunately, strategies designed to enhance cellular uptake of gene complexes often lead to increased cytotoxicity and shortened blood circulation time. To address these issues, stimulus-responsive chemistry has been employed to develop multifunctional gene vectors. For instance, polyester-based hydrophobic polymers are used to modify PEI molecules, promoting the self-assembly of nanoparticles through hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions [92]. In this configuration, the hydrophobic polymers form the core, while PEI, as the hydrophilic component, primarily resides in the shell layer. These nanoparticles exhibit the enhanced cellular uptake, driven by stronger electrostatic attractions arising from the higher surface charge density resulting from PEI aggregation. Once inside the cell, the hydrophobic core undergoes esterase-responsive degradation, reducing the positive charge density and decreasing cytotoxicity.

Considering the overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 (MMP-2) at ischemic sites, literature developed an MMP-2 responsive strategy for gene vectors to extend bloodstream retention and enhance cellular uptake. This approach modifies gene complexes with TAT peptide and polyethylene glycol (PEG). PEG is covalently attached via a peptide linker designed with MMP-2 responsive cleavage functionality. The PEG coating provides stability and prolongs circulation time in the bloodstream. Upon reaching ECs, the PEG coating is cleaved by MMP-2, exposing the TAT peptide on the surface of the gene complex, which enhances cellular uptake (Fig. 4) [38].

Fig. 4.

MMP-2 responsive strategy for gene complexes. Created in https://BioRender.com

Improving the specificity of gene delivery is crucial for minimizing side effects. Targeting ligands, including peptides, antibodies, aptamers and carbohydrates, are frequently used to modify gene vectors for cell-specific gene delivery. For example, gene vectors constructed from block copolymers and cationic peptides are modified by REDV peptide to promote the selective gene uptake by ECs [93–97]. Likewise, the molecular modification applying Cys-Ala-Gly (CAG) peptide also demonstrate comparable targeting efficacy [98]. Other targeting ligands, such as the YPSMA-1 monoclonal antibody for prostate cancer cells [99]. Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide or folic acid for cancer cells [100–102], mannose for macrophages [103–105], and Val-Ala-Pro-Gly (VAPG) peptide for vascular SMCs [106–108], have been utilized to improve cell-specific gene delivery.

Endo/lysosomal escape

After entering cells, most gene complexes are entrapped in early endosomes, which subsequently mature into late endo/lysosomes, hindering their release into the cytoplasm to perform the intended function. This process involves two critical changes: a rapid acidification in pH (from near-neutral to approximately 4.5) and the recruitment of hydrolytic enzymes, including cathepsins, acid phosphatases, and nucleases [109]. These enzymes compromise the integrity and functionality of gene complexes, diminishing gene delivery efficiency. Quantitative analyses reveal that only 1–2% of the internalized genes escape from endo/lysosomes and reach the cytoplasm, even with advanced lipid-based nanoparticles [110]. Consequently, the rapid escape of gene complexes from endo/lysosomal compartments is essential to preserving gene bioactivity and ensuring effective delivery. Several mechanisms and strategies to facilitate endo/lysosomal escape are introduced (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Strategies for facilitating endo/lysosomal escape of non-viral vectors. Created in https://BioRender.com

Membrane rupture

The “Proton sponge effect” is a well-recognized mechanism for facilitating endo/lysosomal escape. It occurs when substances with proton-buffering properties become protonated within acidic environment of endo/lysosome. Protonation triggers an influx of chloride ions and water from cytoplasm, leading to osmotic swelling and subsequent rupture of the endo/lysosomal membrane [111]. This rupture enables the release of gene complexes into the cytoplasm. Utilizing this phenomenon, researchers have designed and synthesized various gene carriers.

PEI polymer, rich in primary, secondary and tertiary amines, exhibit proton-buffering capabilities, making them a popular choice for developing gene carriers. For instance, modifying low-molecular-weight PEI with degradable PLGA polymer not only achieves endo/lysosomal escape, but also reduces cytotoxicity [112–115]. Extending low-molecular-weight PEI chains with reducible bifunctional crosslinkers has been shown to enhance endo/lysosomal escape efficiency [116].Other polymers, such as poly (dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) (PDMAEMA) and polyhistidine, are also used to construct gene carriers due to proton sponge properties [117–120]. Notably, star-shaped PDMAEMA, synthesized via atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), exhibits optimal endo/lysosomal escape. Modifications to gene carries with varying lengths of polyhistidine chains have revealed that increasing the number of histidine residues from 4 to 12 helps endo/lysosomal escape.

Recent advancements introduce novel strategies, such as inducing singlet oxygen (1O2) generation under light irradiation, to directly disrupts endo/lysosomal membrane and facilitates gene escape into cytoplasm. For example, the co-assembly of aggregation-induced emission photosensitizers with genes into nanoparticles. Upon cell internalization into endo/lysosomes, a simple light exposure (60 mW cm-2 ) for 10 min is performed to generate 1O2 effectively disrupt membrane structure and enhance gene escape [121].

Moreover, nanomechanical movements induced by harnessing photons can also assist the carrier in achieving endo/lysosomal escape. Zhao et al. developed an artificial lipid-based molecular machine (LNM) composed of photoisomerable azo-based lipidoids and helper lipids. The reversible isomerization of azo-based lipidoids, triggered by simultaneous UV/Vis irradiation, drives continuous rotation − inversion and stretch − shrink motions. After entering cells, LNMs interacted with the endo/lysosomal membranes, where azo-based lipidoids acted as rotors, destabilizing the membranes and enabling efficient endo/lysosomal escape [122].

Pore formation and membrane fusion

Promoting endo/lysosomal escape can also be achieved through mechanisms involving pores formation or membrane fusion facilitated by gene carriers. Researchers have developed pH-sensitive peptides, such as KALA and GALA, which adopt random coil structures under neutral conditions but transform into amphiphilic α-helical structures in acidic environments. This conformational change is driven by the protonation of specific amino acid residues, allowing these peptides to integrate into the endo/lysosomal membrane and form pores that enable gene escape [123, 124]. Additionally, certain cationic liposomes, often containing dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) as a helper lipid, are employed as gene carriers. Once inside the endo/lysosome, these liposomes interact electrostatically with the membrane via their positive charges, destabilizing it and inducing membrane fusion, thereby releasing gene cargos into the cytoplasm [125].

Nuclear uptake

Following successful escape from endo/lysosomal compartments and entering cytoplasm, gene complexes must cross the nuclear envelope to reach nucleus for initiating gene transfection. Natural viruses, renowned for their capacity to transport genetic material into the nucleus, have provided insights into the mechanisms of nuclear entry. Studies reveal that viruses achieve efficient nuclear translocation primarily through interactions between nuclear localization sequences (NLS) and nuclear pore complexes. The first NLS peptide, Pro-Lys-Lys-Lys-Arg-Lys-Val (PKKKRKV), derived from the T antigen of simian virus 40 (SV40), is known for its ability to direct biomacromolecules into the nucleus [126]. This discovery has inspired the widespread application of NLS in the design of gene carriers to enhance nuclear targeting.

Researchers have synthesized hybrid peptides, such as NLS-R8, which combine the NLS with the cell-penetrating peptide R8 to facilitate gene delivery [126]. Experimental results demonstrate that the introduction of NLS peptide increases the gene accumulation within the nuclear. Moreover, N-terminal modification of the NLS-R8 peptide with stearic acid further enhances gene delivery efficiency and nuclear localization. This enhancement is mainly attributed to the hydrophobic nature and self-assembly properties conferred by the stearic acid modification.

NLS peptides are frequently employed to modify cationic polymers and liposomes, enhancing the nuclear targeting capability of gene carriers. A multifunctional gene carrier has been developed by linearly integrating an EC-targeting peptide (REDV), a cell-penetrating peptide (TAT), and the NLS peptide. This design simultaneously enhances selective uptake by ECs, promotes endo/lysosomal escape, and improves nuclear entry [127]. Transfection experiments reveal a colocalization ratio of the delivered gene with the nucleus reached 19.8% after 24 h, indicating a enhancement in nuclear delivery.

In summary, biomaterial-based gene delivery systems for vascularization represent promising progress in advancing gene delivery strategies. Efforts to optimize gene loading, facilitate endo/lysosomal escape, and improve nuclear localization have contributed to more effective gene transfection. The application of biomaterials has shown potential in enhancing the stability, specificity, and efficiency of these systems, offering valuable insights for therapeutic vascularization.

Biomaterial-enhanced cell therapeutic strategies for vascularization

Findings on somatic stem and progenitor cells, including bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), have provided insights into their potential for therapeutic vascularization [128]. Stem cells are reported to support vascularization through four primary mechanisms [129, 130]. Firstly, they possess the ability to differentiate into ECs directly. The second and most prominent mechanism is their paracrine effects, demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo [131]. These paracrine factors include angiogenic molecules such as FGF-2, VEGF, and TGF-β. Under pathological conditions like hypoxia, the secretion of these factors is upregulated. Lastly, they can mediate intercellular communication through the release of exosomes and migrasomes, enhancing the signaling processes of angiogenic factors [132, 133]. The following sections will examine these four mechanisms, their roles in vascularization strategies, and how biomaterials help address the limitations of cell-based therapies to improve their potential effectiveness (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Biomaterials enhance stem cell mechanisms for promoting vascularization. Created in https://BioRender.com

Directional differentiation

MSCs are found in umbilical cord blood, the placenta, muscle, and other tissues, with bone marrow and adipose tissue being the main sources. Experiments in vivo and in vitro have confirmed that MSCs, regardless of their origin, can differentiate into ECs [134–136]. Numerous studies indicate that autologous stem cell therapy offers advantages over conventional treatments for PAD by promote vascularization and cellular proliferation, enhancing growth factor expression as well as increasing the density of small blood vessels [137].

However, the efficacy of cell therapeutic strategies is often constrained by the low retention and survival rates of injected cells, with only 1–3% of cells successfully migrating to and remaining in the affected parenchyma [138]. Encapsulation of cells in injectable hydrogels or other tissue-engineering scaffolds, which offer mechanical protection against cell membrane damage during syringe flow, has proven the benefits to address these challenges. For instance, researcher developed a shear-thinning injectable recombinant hydrogel to improve the viability of encapsulated induced pluripotent stem cell-derived ECs in murine PAD models [139]. Composed of multi-arm poly (ethylene glycol) with cell adhesion peptides and thermo-responsive poly (N-isopropyl-acrylamide) (PNIPAM), this hydrogel dynamically adjusts its mechanical properties, with viscosity decreasing to 0.5–2 Pa·s under high shear rates and self-healed to 20–100 Pa·s within 1 s under low shear rates The thermal phase transition of PNIPAM, with lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of 32 °C, provides secondary crosslinking in situ to stiffen the hydrogel network, improving cell retention, proliferation and vascularization factor secretion.

Expanding on this concept, a different approach polymerized bioactive gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) with 2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethyl methacrylate (MEO2MA) and 2-[3-(6-methyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-yl)ureido] ethyl methacrylate (UPyMA) to generate one hybrid branched copolymer [140]. This hydrogel undergoes rapid gelation above its LCST, where PMEO2MA segments dehydrate and assemble into clusters, providing a hydrophobic microenvironment that facilitate UPy dimerization to connect polymer chains, thus forming quadruple hydrogen bond reinforced crosslinking networks. MSCs delivered within the in situ formed hydrogel are safeguarded against mechanical damage and exhibit improved long term cell retention in vivo.

To further mitigate the mechanical stress encountered during injection, a dynamically responsive laminin-inspired hydrogel was designed. By incorporating a functional peptide domain from laminin (Fmoc-DDIKVAV), the hydrogel spontaneously assembles to form a nanofibrous scaffold, creating a safe sanctuary microenvironment that mitigates mechanical damage caused by droplet formation and shear stress during injection, supporting enhanced cell viability [141]. Their experiments indicate that cell survival is influenced mechanistically more by the fluid mechanic processes of droplet formation (as opposed to continuous flow) than on the simple shear rate, as this threshold fluid behavioral observation correlated with the measured cell viability.

In another advancement, polymer-nanoparticle hydrogels with non-Newtonian were employed to enhance cell viability during injection [142]. Synthesized by mixing of dodecyl-modified hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (HPMC-C12) with PEG-b-PLA nanoparticles (NP), these hydrogels were tailored to reduce the pressure needed for injection and minimized cell damage by maintaining low shear stress during injection process. As a result, cell viabilities, including MSCs, remained consistently above 86% across various cell types when injected with the hydrogel, compared to the 68% viability observed with PBS injection.

Paracrine effects

Recent studies highlight that the therapeutic benefits of MSCs for vascularization are largely attributed to their paracrine effects, rather than differentiation potential [143]. These cells exhibit paracrine activity via releasing a variety of bioactive molecules, including cytokines, antioxidant agents, chemokines, and growth factors, which mediate cell cross-talk and coordinate processes like immunomodulation, cell recruitment, and vascularization for tissue repair [144]. But several limitations hinder the practical application of paracrine effects-based therapies. The low survival rate of transplanted stem cells in damaged tissues limits sustained growth factor secretion. Uneven and transient growth factor release, along with challenges in controlling cell localization, compromises effective and long-lasting vascularization [145]. Biomaterials present promising solutions to these challenges. Engineered biomaterials enable controlled and sustained release of growth factors, ensuring a stable and concentrated angiogenic stimulus. Precise spatial structuring facilitates targeted cell placement and creates optimized microenvironments for neovascularization, enhancing therapeutic efficiency and specificity. Next, we will briefly introduce several specific applications of biomaterials in enhancing paracrine effects.

For instance, Katare et al. developed a novel miniaturized encapsulation procedure, where stem cell-containing core beads were encased in a permeable shell of biocompatible alginate microbeads [146]. This shell provided robust immuno-isolation while allowing the diffusion of paracrine factors, such as VEGF. The optimized shell-to-core ratio ensured full cell viability. The formulation contained the human MSCs genetically modified to express glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone with proangiogenic effects. The technology enabled long-lasting cell retention at transplantation site and integrated the native paracrine activity of MSC with their ability to produce and secrete GLP-1. After femoral artery ligation in mice, treatments applied to perivascular space enhanced the activation of angiogenesis-related genes, such as endoglin, VEGF-A, sphingosine kinase 1, angiopoietin 4, interleukin-8, and heparanase. It also led to a reduction in the expression of β2-microglobulin, a biomarker of PAD, as well as downregulated several antiangiogenic genes, including tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 2 and 3, thrombospondin 2.

Biological scaffolds, with their unique biophysical structures and functions, such as porous structure, functional groups and controllable degradation rate, stimulate paracrine effects in cells through specific cell-material interactions [147, 148]. Currently, emerging processing technologies, including 3D printing, low-temperature deposition modeling (LDM) method, electrostatic spinning, and stereolithography are undergoing continuous advancements to enable precise parameter tuning, better meeting the evolving demands for scaffold material development [149]. Lian et al. constructed a bioengineered scaffold from a copolymer of poly (L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLCL) and nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) using LDM to create hierarchical, interconnected pores, followed by freeze-drying to remove solvents and form stable, porous sponge-like structures [150]. The hierarchical porous structure enhanced paracrine functions of MSCs by promoting cell-material interactions. The scaffold’s interconnected micropores and increased surface roughness facilitated the adhesion, survival, and infiltration of MSCs. This design modulated key cellular pathways, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Yes-associated protein (YAP) signaling, which were involved in mechanotransduction. These pathways increased the secretion of paracrine factors, including proangiogenic factors like VEGF, immunomodulatory factors like PGE2 and COX2, which promoted vascularization. This therapeutic potential was validated in a rat distal femoral defect model (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

LDM-printed porous sponge-like scaffolds for enhancing cell-scaffold interaction and modulating msc paracrine functions. Created in https://BioRender.com

Nanofiber scaffolds, fabricated through electrospinning technology with varying topological structures, have the capacity to generate topographically driven signals that intricately modulate the paracrine interactions of cells [151]. Liu et al. reported that a series of nanofiber-based meshes were fabricated by electrospinning and light-welding technology to enhance the paracrine effects of ADSCs, particularly for the overexpression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and FGF2, two canonical growth factors associated with tissue repair [152]. The hydrophilic surface and microstructure of electrospinning nano-polymer scaffolds impacted cell adhesion, growth, proliferation, and extension. By modulating surface topologies, such as grooves, micropillars, and microporous array structures, the spreading morphology and area of the cells can be precisely controlled, influencing their physiological behaviors. The results showed that the migration of fibroblast and ECs, as well as angiogenesis was improved in vitro owing to the paracrine products of ADSCs after being cultured on the nanofiber-based meshes.

Loading nanoparticles carrying therapeutic transgenes onto biomaterial scaffolds is another strategy to enhance paracrine effects. Laiva et al. developed a collagen-chondroitin sulfate scaffold functionalized with nanoparticles carrying plasmid DNA encoding the β-Klotho gene [153]. The scaffolds were fabricated by freeze-drying collagen and chondroitin sulfate, followed by cross-linking with a chemical agent to improve mechanical stability and then soaked with polyplexes of branched PEI and β-Klotho plasmid. The gene-activated scaffold transiently enhanced ADSCs’ stemness through the activation of transcription factor Oct-4. It is a key transcription factor in embryonic stem cells, crucial for regulating their pluripotency [154].The conditioned media from ADSCs cultured on the gene-activated scaffold enhanced the tube-formation of human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) by promoting paracrine bioactivity. Regrettably, the article does not report in vivo testing in animals. It was also noteworthy that the recent studies elucidated a novel paracrine mechanism in which the bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells facilitate vascularization. This process primarily involves the downregulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), resulting in the subsequent upregulation of eNOS activity, thereby promoting enhanced vascularization [155].

Exosome

Exosomes play a critical role in vascularization therapy for PAD. These 30–150 nm extracellular vesicles, released through the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with plasma membrane, transport various biomolecules such as proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs, which influence the behavior of adjacent and distant cells [156]. However, when applied to therapeutic vascularization for PAD, exosomes face several barriers, including limited exosome secretion capability of cells, rapid clearance from the administration site, poor targeting and inadequate retention in ischemic tissues, resulting in the diminished therapeutic efficacy. To address these issues, biomaterials such as hydrogels and scaffolds were employed to prolong exosome retention, enabling the sustained release of pro-angiogenic factors. These biomaterials also enhanced exosome targeting and local concentration, improving their therapeutic potential in PAD treatment [157].

The capacity of cells to generate exosomes is governed by a multitude of factors, such as cell type, viability, and the characteristics of the culture microenvironment. Leveraging biomaterials to concurrently augment exosome production and tailor their biological functionality represents an approach. For example, Wu et al. enhanced the yield and biological properties of stem cell-derived exosomes by culturing MSCs in a medium containing 45S5 Bioglass® (BG) ion products, which created a favorable microenvironment for MSCs [158]. Composed of 45% SiO₂, 24.5% Na₂O, 24.5% CaO, and 6% P₂O₅ (weight%), BG ion products increased the production of exosome by upregulating the neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (nSMase2) and Rab proteins 27a (Rab27a) pathways, which were crucial for exosome biogenesis and release. nSMase2 facilitated intraluminal vesicle formation through ceramide production [159], while Rab27a aided in docking at and fusion with plasma membrane of MVBs to release exosome vesicles [160]. BG-stimulated MSCs also secreted exosomes with the altered microRNA profiles, downregulated miR-342-5p, a molecule known to inhibit the vascularization [161], and upregulated miR-1290, which was implicated in tumor initiation, invasion, and metastasis [162], thereby enhancing their ability to promote vascularization (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

BG ion products enhance msc-derived exosome production and release. Created in https://BioRender.com

Another approach involves leveraging biomaterial-derived chemical signals to modulate exosomal miRNAs and their downstream proteins, thereby facilitating cell-cell communication between MSCs and ECs to enhance vascularization. Liu et al. designed a 3D-printed lithium-incorporated bioactive glass ceramic that enhanced the vascularization capacity of HUVECs by promoting the expression of miR-130a in BMSC-derived exosomes, a process driven by the release of Li+ from the biomaterials, which leads to the downregulation of PTEN and activation of AKT signaling pathway, and increased the expression of VEGF, ANG1, KDR and PDGF [163].

The application of exosomes in site-specific drug delivery necessitates surface modification to facilitate targeted delivery to the desired site of action. Exosome surface modification strategies include a range of approaches, such as genetic engineering, covalent modifications, and non-covalent modifications, including multivalent electrostatic interactions, ligand-receptor binding, hydrophobic interactions, aptamer-based modifications, and ischemia-targeting peptides. These strategies enable the effective targeting of specific organs by exosomes [164]. For instance, Tian et al. improved the targeting capabilities of exosomes for cerebral ischemia therapy by conjugate functional ligands, the cyclo (Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Tyr-Lys) peptide [c(RGDyK)], onto exosomal surfaces using bio-orthogonal copper-free azide alkyne cyclo-addition (click chemistry) [165]. The c(RGDyK) peptide, which binds to integrin αvβ3 expressed on reactive cerebral vascular endothelial cells following ischemia. This method involved introducing reactive dibenzylcyclootyne (DBCO) groups onto exosomes via a crosslinker, followed by performing the reaction of DBCO with azide-modified c(RGDyK), which formed a stable triazole bond.

To prolong the circulation time and specifically target ischemic limbs of exosomes and oxygen-releasing nanoparticles delivered by intravenous injection, Zhong et al. cloaked them with a CSTSMLKAC (CST) peptide-functionalized platelet membrane [166]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the platelet membrane can effectively “disguise” nanoparticles in the bloodstream. CST, an ischemia-targeting peptide, was used for this purpose. Researcher revealed that the CST-conjugated platelet membrane enabled the nanoparticles to preferentially accumulate in the ischemic limbs, likely through the vasculature surrounding the ischemic region and the permeable vessels within it. The delivered exosomes and oxygen-releasing nanoparticles worked synergistically to reduce cell apoptosis, promote cell proliferation and mitochondrial metabolism, and enhance the expression of angiogenic growth factors.

The combined use of hydrogels can prevent the premature clearance of exosomes. By directly placing hydrogels containing exosomes at or near the target site, a more concentrated dose is ensured, leading to sustained and enhanced therapeutic effects. Various forms of hydrogels have been proven to possess these functions. For instance, a thermal-/pH-responsive hydrogel, prepared by Pluronic F127, PEI, and oxidized dextran, served as a sensitive controlled-release carrier and improved the stability of transcription factor EB-exosomes in vivo, simultaneously [167]. Han et al. incorporating miR-675 into exosomes encapsulated in silk fibroin hydrogel, which maintained the stability of exosomal miR-675, resulting in an improvement of therapeutic effects of miR-675 exosomes [168]. Zhang et al. evaluated the use of chitosan hydrogel, which increased the stability of proteins and miR-126 in exosomes, as well as improved the retention of exosomes in vivo, enhancing the therapeutic effects for hindlimb ischemia [169].

Migrasome

The recent discovery of migrasomes, organelles generated during cell migration that mediate intercellular communications, has unveiled a new avenue for therapeutic intervention. Studies have shown that the migrasome derived from mononuclear cells are enriched with angiogenic factors such as VEGFA and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12. These migrasomes promote capillary formation, recruit mononuclear cell, as well as enhance ECs’ tube formation and chemotaxis. This unique capability of recruiting mononuclear cells and stimulating angiogenesis underscores the therapeutic potentials of migrasomes in PAD treatment [170, 171].

Biomaterial-enhanced cell therapeutic strategies have shown potential in addressing the limitations of conventional treatments by improving stem cell retention, amplifying paracrine effects, stabilizing and targeting exosomes, and leveraging the angiogenic potential of migrasomes. Innovations such as dynamic hydrogels, gene-activated scaffolds, and functionalized nanoparticles have contributed to advancements in vascularization therapies. These findings underscore the importance of biomaterials in enabling precise control over cellular and molecular mechanisms to enhance vascularization. By integrating advanced processing technologies and innovative strategies, biomaterials hold promise for contributing to more effective therapeutic outcomes.

Biomaterial-assisted enhancement of protein/peptide approaches for vascularization

Proteins and peptides with specific bioactivity are increasingly being employed as functional biomaterials to facilitate tissue regeneration. These biomolecules modulate cellular functions and behaviors, promoting vascularization. But application of bioactive proteins such as growth factors in biomaterials faces limitations, with one of points is precise dosage control. Insufficient doses may only affect vascular permeability without inducing vascularization, while excessive doses carry a risk of angioma formation. Achieving optimal vascularization effects requires precise dosage calibration. To address these challenges, researchers have devised various strategies utilizing biomaterials to enhance vascularization. Hydrogels are widely used in protein delivery, employing various mechanisms, including diffusion, swelling, chemical interactions (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions), stimuli-triggered responses such as temperature, pH, enzymes, and light to control protein release (Fig. 9) [172, 173].

Fig. 9.

Hydrogel-controlled release of proteins and peptides via diffusion, swelling, chemical, and stimuli-triggered responses mechanisms. Created in https://BioRender.com

Vascular endothelial growth factor

The mammalian VEGF family comprises five different polypeptides: VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D and placental growth factor, among which VEGF-A isoforms are the most prominent in regulating blood vessel growth [174]. VEGF binding to VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) activates downstream signaling pathways, including AKT serine/threonine kinase 1-extracellular signal‐regulated kinase‐endothelial nitric oxide synthase (AKT‐ERK‐eNOS) pathways, which regulates cell proliferation and migration and promotes angiogenesis [175]. Biomaterial have been demonstrated to enable the sustain release of growth factors. For instance, Li et al. created a thermosensitive hyaluronic acid hydrogel with antioxidant capacity and optimized it with the cell adhesion peptide RGD to promote the formation of vascular-like structures in vitro. This hydrogel provided prolonged release of VEGF in a CLI mouse model [176]. A study develops a heparin-based nanocarrier capable of electrostatically binding VEGF-C and VEGF-C, respectively. This nanosystem sequentially released VEGF-C and VEGF-A in ischemic myocardial tissue, facilitating the lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis within myocardium and ultimately improve myocardial functions [177]. Similarly, polycaprolactone scaffolds with porous structures are employed for local VEGF delivery, inducing vascularization within 14 days post-subcutaneous implantation [178].

Fibroblast growth factor

FGF, a single-chain peptide with a molecular weight of 16,000 and composed of 146 amino acids, exhibits mitogenic and chemotactic properties for fibroblasts and ECs, contributing to vascularization [179]. Various biomaterials, such as alginate, heparin-sulfate, dextran, glycosaminoglycans, and poly (ethylene) glycol, have been utilized to create controlled delivery systems for FGF, enabling sustained, localized, and effective dose responses [180].

For instance, Azizian et al. reported that chitosan nanoparticles loaded with basic FGF and bovine serum albumin were incorporated into a chitosan-gelatin scaffold. The experimental results demonstrated that the inclusion of chitosan nanoparticles enhanced the scaffold’s properties, enabling the sustained release of FGF and promoting fibroblast proliferation [181]. Fujita et al. developed an injectable hydrogel composed of chitosan and periodate-oxidized non-anticoagulant heparin (IO₄⁻-heparin) to control the release of FGF-2 [182]. The hydrogel, formed by mixing lactose-modified chitosan with IO₄⁻-heparin, mimicked the natural binding interactions between FGF-2 and heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. The high affinity binding of IO₄⁻-heparin to FGF-2 helped stabilize peptide and prevent its rapid degradation. Layman et al. designed ionic gelatin-based hydrogels by covalently crosslinking gelatin with PLL or poly-L-glutamic acid (PLG) to control the release of FGF-2 for enhanced vascularization in a murine CLI model [183]. The ionic properties of hydrogels regulated FGF-2 release, with the anionic gelatin-PLG hydrogel providing controlled release due to electrostatic interactions with positively charged FGF-2.

Pleiotrophin

Pleiotrophin (PTN), a heparin-binding factor with vascularization activity. To enhance PTN binding to the gel and extend its release duration, heparin was incorporated into the standard gel formulation. For instance, Rountree et al. developed an injectable hydrogel composed of heparin-modified alginate and chitosan for the controlled release of PTN [184]. Heparin moieties were chemically cross-linked to alginate using carbodiimide chemistry, enabling stable PTN incorporation. Calcium carbonate was used for internal gelation to produce a uniform gel suitable for subcutaneous injection. The hydrogel delivered PTN in a controlled manner over 7 days, as confirmed by in vivo and in vitro release kinetics. The hydrogel enhanced PTN bioavailability, facilitated new blood vessel formation by interacting with ECs and macrophage cells in ischemic regions.

Angiopoietin-1

Ang-1 is a ligand of Tie-2 receptors that promotes blood vessel maturation, and also commonly used to enhance vascular regeneration. Kang et al. utilized a three-dimensional stem cell cluster approach combined with Ang-1 to the enhanced vascularization [185]. Human adipose-derived stem cells were cultured on a maltose-binding protein-linked basic FGF surface to form stable three-dimensional clusters. The angiocluster system enhanced paracrine signaling by secreting key angiogenic factors, such as VEGF and IL-8, promoting the proliferation and angiogenesis of endothelial cell. Ang-1 further reinforced vascularization, improved the retention and survival of transplanted cells in ischemic tissues. This combination therapy increased blood vessel regeneration and reduced tissue fibrosis, leading to the improved limb salvage in a mouse hindlimb ischemia model.

Bioactive peptides

Recent studies highlight several bioactive peptides with proangiogenic property. For example, poly-L-arginine can be internalized by ECs and act as a precursor of NO to enhance the production of NO for the facilitation of vascularization via eNOS/NO signaling pathway [186]. Another study develops the nanomicelles based on poly-L-arginine, which is used to culture HUVECs in vitro to promote vascularization [187]. Pan et al. investigated a 7-amino acid peptide (7 A, MHSPGAD) derived from histone deacetylase 7 for its role in vascular repair and regeneration [188]. This peptide promoted the migration and differentiation of vascular progenitor cells into ECs, as confirmed by endothelial markers PECAM-1 and CD144, and tube formation assays. In vivo, its vascularization effects were evaluated in a CLI models, with local delivery via Pluronic-127 gel. Periostin, a matricellular protein, facilitates vascularization by stimulate the migration of ECFCs through an integrin β5-dependent mechanism. To enhance the in vivo delivery efficiency of periostin peptide, Kim et al. utilized a lumazine synthase protein cage nanoparticle as a template and genetically fused 10 amino acids of periostin peptide (WDNLDSDIRR) (amino acid sequences 142–151 of periostin) to form the nanoparticles. These periostin peptide-decorated protein cage nanoparticles promoted migration, tube formation, and proliferation of ECFCs, promoteing vascularization in ischemic limbs [189].

Metal ion-based biomaterials for therapeutic vascularization

Metal ions are essential for human life activities, contributing to metabolic regulation, physiological function maintenance, and tissue repair and regeneration. Therefore, there is increasing interest in developing biomaterials based on metal ions for applications of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Recently, several metal ions, including europium, copper, zinc, strontium, and cerium, have been recognized for their proangiogenic properties, driving the development of functional biomaterials to enhance vascularization.

Europium ions

For assess the vascularization activity, researchers developed europium hydroxide nanorods capable of being internalized by ECs. These nanorods generate superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide for the activations of redox-sensitive signaling pathways. This activation upregulates the expression of VEGF and FGF, thereby inducing ECs proliferation, migration, and vascularization [190].

Zinc ions

Literature has reported that nanoscale zinc-based MOFs can deliver zinc ions to ECs, promoting vascularization and improving blood flow in ischemic limbs of CLI mouse models. Furthermore, by incorporating EC-targeting peptide and a mitochondrial targeting peptide, we optimized zinc ion delivery to the mitochondria of ECs. This approach enhanced vascularization while reducing the required dosage by nearly two orders of magnitude [191].

Copper ions

Copper ions are well-known for their proangiogenic properties, inspiring the development of nanoscale copper-based metal-organic frameworks to deliver copper ions directly into ECs to promote vascularization. This approach has demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in accelerating wound healing in diabetic mouse models [192]. Additionally, a metal-polyphenol capsule formed from copper and epigallocatechin-3-gallate was shown to induce VEGF secretion and increase vascularization in a hindlimb ischemia model, attributed to the upregulation of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen [193].

Terbium

Basuthakur et al. synthesized terbium hydroxide nanorods (THNR) via an aqueous chemical process, resulting in rod-shaped nanostructures that were purified and characterized for their composition and structure [194]. THNRs exhibited vascularization effects by enhancing ECs function under ischemic conditions, primarily through activation of the PI3K/AKT/eNOS signaling pathway, which increased NO production, a mediator in vasodilation and angiogenesis. THNRs also modulated Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway to promote proliferation and migration of ECs, while reducing oxidative stress by lowering ROS levels. In a murine model of CLI, THNRs protected against ischemia-induced injury, improved vascular integrity, and enhance blood flow recovery, highlighting their therapeutic potential in ischemic conditions.

Strontium ions

Strontium ions have recently gained recognition for their vascularization effect. one study utilizes strontium-containing injectable hydrogel for the sustained delivery of strontium ions into myocardial tissues, resulting in the increased vascularization, reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and alleviation of ischemia-reperfusion injury to the heart [195]. Yuan et al. designed a strontium carbonate/calcium silicate/sodium alginate composite hydrogel that effectively released Sr2+, SiO32− and Ca2+ ions [196]. The hydrogel’s injectability was achieved through dual-crosslinking of alginate with Sr2+ and Ca2+ ions. Over 28 days, the hydrogel enhanced vascularization by releasing Sr2+ and SiO32−, which stimulated proliferation of ECs and SMCs (Fig. 10). It also upregulated the expression of VEGF and HIF-1α, accelerating the reconstruction of vascular network. Furthermore, the released ions facilitated macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype, fostering a regenerative microenvironment.

Fig. 10.

The hydrogel, with injectability was achieved through dual-crosslinking of alginate by Sr2+ and Ca2+ ions gradually released from SrCO3 and CaSiO3, promoted vascularization to restore blood supply in the hind limb. Created in https://BioRender.com

Cerium ions

Cerium dioxide nanoparticles are known to modulate the oxygen environment within ECs, leading to the overexpression of HIF-1α and enhanced vascularization in vitro and in vivo. The physicochemical properties of cerium dioxide nanoparticles about Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio, are critical for their oxygen-modulating activity for further promoting HIF-1α expression and vascularization [197].

It is noteworthy that metal ion-based strategies offer distinct advantages in terms of cost-effective and stable properties, compared with gene, protein, and peptide-based approaches. However, therapeutic efficacy and safety must be carefully evaluated, as excessive local concentrations of metal ions can exceed human tolerance threshold and induced metal toxicity.

Overview of recent and ongoing clinical trials in PAD treatment

Building upon the findings from preclinical studies, real-world investigations have further solidified our understanding by translating these insights into clinical practice. Among these, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving individuals with PAD play a pivotal role, advancing the treatment approaches by demonstrating potential of novel pharmacotherapy, endovascular procedures, and non-invasive interventions to enhance functional outcomes.

Recent and ongoing RCTs are investigating pharmacotherapy such as nicotinamide riboside (NR) [198], metformin [199–201], mirabegron [202], cocoa flavanols [203], beetroot juice [204], and colchicine [205], targeting improvements in functional outcomes like pain-free exercise tolerance and limb perfusion. For example, the NICE trial demonstrated that NR (n = 28) improved the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) by 17.6 m at 6 months, with participants achieving at least 75% adherence and showing an increase of 31.0 m, and NR combined with resveratrol (n = 33) improving it by 26.9 m compared to placebo (n = 28) [198]. The COCOA-PAD trial highlighted that cocoa flavanols (n = 23) increased 6MWD by 42.6 m after 6 months compared to placebo (n = 21) [206]. The NO-PAD trial showed that exercise plus beetroot juice (n = 11) improved pain-free walking by 121.1 s (a 200% increase over exercise alone) and increased 6MWD by 28.8 m compared to exercise plus placebo (n = 13) [207].

Each pharmacological intervention brings distinct advantages and limitations. NR, a precursor of NAD+, enhances mitochondrial function and nitric oxide bioavailability [208], demonstrating promising efficacy in clinical trials for PAD treatment, but its results require further confirmation in larger studies. Metformin shows promise for PAD with its pro-mitochondrial, anti-inflammatory properties and potential to promote arteriogenesis [209, 210], but ongoing RCTs have yet to provide conclusive results. Mirabegron enhances muscle oxygenation but has variable efficacy and cardiovascular risks [211]. Cocoa flavanols and beetroot juice enhance antioxidant capacity in PAD via Nrf2 activation and production [212, 213], but their short-lived, diet-dependent effects and the potential carcinogenic risk of nitrites in beetroot juice limit their long-term applicability.

In parallel, over 30 RCTs in the past decade have focused on lower-extremity endovascular interventions. The most common procedures are drug-coated balloons/drug-eluting balloons, followed by drug-eluting stents/drug-coated stents, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, and bare metal stents [214]. These procedures have demonstrated success in restoring blood flow and enhancing limb perfusion, though long-term follow-up is required to evaluate complications such as restenosis. Additionally, biomaterial-based approaches like acellular tissue-engineered vessels (ATEVs) have shown promise [215]. Composed of extracellular matrix proteins cultured from human vascular cells and rendered acellular, ATEVs have demonstrated 87.1% primary patency and 91.5% secondary patency at 30 days, with low infection rates of 0.9% in 86 patients with acute arterial injuries [216]. Long-term studies over three years indicate mechanical durability without significant complications, suggesting potential applications for PAD treatment.

In addition to pharmacological and endovascular interventions, the non-invasive interventions, such as heat therapy [217], footplate muscle stimulation [218], weight loss and home exercise [219], intermittent pneumatic compression [220], are essential complements in PAD management, with ongoing RCTs investigating their efficacy. These advancements reflect a growing shift toward personalized, multimodal treatment strategies, combining pharmacotherapy, advanced biomaterials, optimized revascularization techniques and lifestyle interventions to enhance vascular regeneration and functional outcomes.

Challenges and future outlooks

Biomaterial-based therapeutic vascularization strategies have exhibited potentials in treating PAD. Functional biomaterials designed to mimic the biochemical properties of extracellular matrix provide both structural support and precise, sustained delivery of vascularization factors. Bioactive hydrogels and 3D-printed scaffolds have improved cellular integration and localized delivery, enhancing EC functionality and promoting the neovascularization of ischemic tissues. Incorporating stem cell-derived exosomes into these biomaterials has expanded therapeutic potential of paracrine signaling, with exosomes serving as potent carriers for simultaneous delivery of multiple angiogenic factors. Furthermore, functionalized peptides have been employed to refine the targeting and retention of therapeutic agents within ischemic regions, further optimizing the efficacy.

Despite these advancements, several challenges continue to hinder the clinical translation of these therapies. A major obstacle is the low retention and survival rate of transplanted cells and bioactive agents within harsh ischemic microenvironment. The host immune response against synthetic biomaterials drives inflammation, which in turn compromises the bioactivity of embedded vascularization factors. Ensuring long-term functional stability of biomaterials in dynamic tissues is also challenge, as mechanical mismatches between biomaterial and host tissue frequently result in premature material degradation or fibrosis. Moreover, achieving precise spatiotemporal control over the release of vascularization factors and cells remains a technical hurdle, as current delivery methods are often failed to replicate the complex natural gradients and microenvironments essential for effective tissue repair.

Future research is considered to focus on the development of multifunctional biomaterials that integrate immunomodulatory agents with vascularization factors to mitigate inflammation and enhance the integration of transplanted cells or therapeutic agents with host tissues. Bioactive scaffolds capable of sensing and responding to the ischemic microenvironment (releasing growth factors or cells only in response to specific biological cues), such as pH or oxygen levels, are expected to gain increasing prominence. Incorporating vascularization genes into scaffolds for sustained and localized gene expression, hold promise for enhancing tissue repair. Advancements in nanotechnology are also poised to provide control over cellular behavior, facilitating precision manipulation of stem cells and their paracrine outputs, which could enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Another promising avenue involves oxygen-releasing biomaterials, which are designed to improve the survival of transplanted cells in the ischemic environment, thereby augmenting their therapeutic efficacy. Magnetic or ultrasound-guided targeting systems are likely to be further explored as non-invasive strategies for directing therapeutic agents to specific sites within body. The integration of machine learning algorithms into the design of biomaterials may offer new possibilities for optimizing scaffold properties tailored to individual patient conditions, and advancing personalized treatment strategies for PAD.

Collectively, these emerging innovations will push the boundaries of regenerative medicine, facilitate effective therapies for PAD, and ultimately improve limb salvage and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

H.W.: Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. F.L.: Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Y.Z.: Methodology, Investigation. Y.L.: Methodology, Investigation. B.G.: Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. D.K.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82302372 and No. 82171327); Fujian Provincial Health Commission (2022ZD01003); Major Scientific Research Program for Young and Middle-aged Health Professionals of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2023ZQNZD005); Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (2024J01537); Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2023Y9031).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Haojie Wang and Fuxin Lin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bin Gao, Email: GBIN000@163.com.

Dezhi Kang, Email: kdz99988@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1.Nordanstig J, Behrendt CA, Bradbury AW, de Borst GJ, Fowkes F, Golledge J, Gottsater A, Hinchliffe RJ, Nikol S, Norgren L. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) - a challenging manifestation of atherosclerosis. Prev Med. 2023;171:107489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eid MA, Mehta K, Barnes JA, Wanken Z, Columbo JA, Stone DH, Goodney P, Mayo SM. The global burden of peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2023;77:1119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Birmpili P, Atkins E, Johal AS, Waton S, Williams R, Boyle JR, Harkin DW, Pherwani AD, Cromwell DA. Illness trajectories after revascularization in patients with peripheral artery disease: a unified approach to understanding the risk of major amputation and death. Circulation. 2024;150:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, Hands L, Silver LE, Rothwell PM. Population-based study of incidence, risk factors, Outcome, and prognosis of ischemic peripheral arterial events: implications for prevention. Circulation. 2015;132:1805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Haelst S, Koopman C, den Ruijter HM, Moll FL, Visseren FL, Vaartjes I, de Borst GJ. Cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with intermittent claudication and critical limb ischaemia. Brit J Surg. 2018;105:252–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceccato D, Ragazzo S, Boscaro F, Avruscio G. Chronic limb-threatening ischemia with no revascularization option: result from a multidisciplinary care model. Eur J Intern Med. 2024;125:137–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xing Z, Zhao C, Wu S, Zhang C, Liu H, Fan Y. Hydrogel-based therapeutic angiogenesis: an alternative treatment strategy for critical limb ischemia. Biomaterials. 2021;274:120872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Kitzerow O, Nie F, Dai J, Liu X, Carlson MA, Casale GP, Pipinos II, Li X. Bioengineering strategies for the treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Bioact Mater. 2021;6:684–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zu H, Gao D. Non-viral vectors in gene therapy: recent development, challenges, and prospects. Aaps J. 2021;23:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenchov R, Sasso JM, Wang X, Liaw WS, Chen CA, Zhou QA. Exosomes horizontal line nature’s lipid nanoparticles, a rising star in drug delivery and diagnostics. ACS Nano. 2022;16:17802–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbarian M, Bertassoni LE, Tayebi L. Biological aspects in controlling angiogenesis: current progress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwee BJ, Seo BR, Najibi AJ, Li AW, Shih TY, White D, Mooney DJ. Treating ischemia via recruitment of antigen-specific T cells. Sci Adv. 2019;5:v6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramoto JS, Teraa M, de Borst GJ, Conte MS. Interventions for lower extremity peripheral artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:332–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim MS, Hwang J, Yon DK, Lee SW, Jung SY, Park S, Johnson CO, Stark BA, Razo C, Abbasian M, et al. Global burden of peripheral artery disease and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e1553–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullo IJ, Rooke TW. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Peripheral artery disease. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:861–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills JS, Conte MS, Armstrong DG, Pomposelli FB, Schanzer A, Sidawy AN, Andros G. The society for vascular surgery lower extremity threatened limb classification system: risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI). J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:220–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wubbeke LF, Kremers B, Daemen J, Snoeijs M, Jacobs MJ, Mees B. Mortality in octogenarians with chronic limb threatening ischaemia after revascularisation or conservative therapy alone. Eur J Vasc Endovasc. 2021;61:350–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golledge J. Update on the pathophysiology and medical treatment of peripheral artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:456–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeshita S, Zheng LP, Brogi E, Kearney M, Pu LQ, Bunting S, Ferrara N, Symes JF, Isner JM. Therapeutic angiogenesis. A single intraarterial bolus of vascular endothelial growth factor augments revascularization in a rabbit ischemic Hind limb model. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song YY, Liang D, Liu DK, Lin L, Zhang L, Yang WQ. The role of the ERK signaling pathway in promoting angiogenesis for treating ischemic diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1164166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandaglio-Collados D, Marin F, Rivera-Caravaca JM. Peripheral artery disease: update on etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin-Barcelona. 2023;161:344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDermott MM, Ferrucci L, Gonzalez-Freire M, Kosmac K, Leeuwenburgh C, Peterson CA, Saini S, Sufit R. Skeletal muscle pathology in peripheral artery disease: a brief review. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2020;40:2577–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haghighat L, Ionescu CN, Regan CJ, Altin SE, Attaran RR, Mena-Hurtado CI. Review of the current basic science strategies to treat critical limb ischemia. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;53:316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espinola-Klein C, Rupprecht HJ, Bickel C, Lackner K, Schnabel R, Munzel T, Blankenberg S. Inflammation, atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular prognosis. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:e126–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown PA, Brown PD. Extracellular vesicles and atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2023;63:107510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, Kearney M, Chen D, Symes JF, Fishman MC, et al. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2567–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonaca MP, Hamburg NM, Creager MA. Contemporary medical management of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2021;128:1868–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canonico ME, Piccolo R, Avvedimento M, Leone A, Esposito S, Franzone A, Giugliano G, Gargiulo G, Hess CN, Berkowitz SD et al. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral artery disease: current evidence and future directions. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, Arya S, Brewster LP, Byrd L, Chandra V, Drachman DE, Eaves JM, Ehrman JK, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the management of lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:2497–604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rosca AC, Baciu CC, Burtaverde V, Mateizer A. Psychological consequences in patients with amputation of a limb: an interpretative-phenomenological analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:537493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooke JP, Meng S. Vascular regeneration in peripheral artery disease. Arterioscl Throm Vas. 2020;40:1627–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu P, Ruan D, Huang M, Tian M, Zhu K, Gan Z, Xiao Z. Harnessing the potential of hydrogels for advanced therapeutic applications: current achievements and future directions. Signal Transduct Tar. 2024;9:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao J, Li Q, Hao X, Ren X, Guo J, Feng Y, Shi C. Multi-targeting peptides for gene carriers with high transfection efficiency. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:8035–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Hao X, Li Q, Akpanyung M, Nejjari A, Neve AL, Ren X, Guo J, Feng Y, Shi C, et al. CAGW peptide- and PEG-modified gene carrier for selective gene delivery and promotion of angiogenesis in HUVECs in vivo. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2017;9:4485–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Zaidi SSA, Hasnain A, Guo J, Ren X, Xia S, Zhang W, Feng Y. Multitargeting peptide-functionalized star-shaped copolymers with comblike structure and a POSS-core to effectively transfect endothelial cells. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2018;4:2155–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao J, Feng Y. Surface engineering of cardiovascular devices for improved hemocompatibility and rapid endothelialization. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9:e2000920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Hao X, Zaidi S, Guo J, Ren X, Shi C, Zhang W, Feng Y. Oligohistidine and targeting peptide functionalized TAT-NLS for enhancing cellular uptake and promoting angiogenesis in vivo. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Su B, Gao B, Zhou J, Ren XK, Guo J, Xia S, Zhang W, Feng Y. Cascaded bio-responsive delivery of eNOS gene and ZNF(580) gene to collaboratively treat hindlimb ischemia via pro-angiogenesis and anti-inflammation. Biomater Sci-Uk. 2020;8:6545–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Long L, Zhang F, Hu X, Zhang J, Hu C, Wang Y, Xu J. Microneedle-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor delivery promotes angiogenesis and functional recovery after stroke. J Control Release. 2021;338:610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moon HH, Joo MK, Mok H, Lee M, Hwang KC, Kim SW, Jeong JH, Choi D, Kim SH. MSC-based VEGF gene therapy in rat myocardial infarction model using facial amphipathic bile acid-conjugated polyethyleneimine. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1744–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qu W, Qin SY, Ren S, Jiang XJ, Zhuo RX, Zhang XZ. Peptide-based vector of VEGF plasmid for efficient gene delivery in vitro and vessel formation in vivo. Bioconjug Chem. 2013;24:960–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dash BC, Thomas D, Monaghan M, Carroll O, Chen X, Woodhouse K, O’Brien T, Pandit A. An injectable elastin-based gene delivery platform for dose-dependent modulation of angiogenesis and inflammation for critical limb ischemia. Biomaterials. 2015;65:126–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vosen S, Rieck S, Heidsieck A, Mykhaylyk O, Zimmermann K, Bloch W, Eberbeck D, Plank C, Gleich B, Pfeifer A, et al. Vascular repair by circumferential cell therapy using magnetic nanoparticles and tailored magnets. ACS Nano. 2016;10:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Browne S, Monaghan MG, Brauchle E, Berrio DC, Chantepie S, Papy-Garcia D, Schenke-Layland K, Pandit A. Modulation of inflammation and angiogenesis and changes in ECM GAG-activity via dual delivery of nucleic acids. Biomaterials. 2015;69:133–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin H, Kanasty RL, Eltoukhy AA, Vegas AJ, Dorkin JR, Anderson DG. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:541–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]