Abstract

Volatile anesthetics including isoflurane affect all cells examined, but their mechanisms of action remain unknown. To investigate the cellular basis of anesthetic action, we are studying Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants altered in their response to anesthetics. The zzz3-1 mutation renders yeast isoflurane resistant and is an allele of GCN3. Gcn3p functions in the evolutionarily conserved general amino acid control (GCN) pathway that regulates protein synthesis and gene expression in response to nutrient availability through phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α). Hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α inhibits translation initiation during amino acid starvation. Isoflurane rapidly (in <15 min) inhibits yeast cell division and amino acid uptake. Unexpectedly, phosphorylation of eIF2α decreased dramatically upon initial exposure although hyperphosphorylation occurred later. Translation initiation was inhibited by isoflurane even when eIF2α phosphorylation decreased and this inhibition was GCN-independent. Maintenance of inhibition required GCN-dependent hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α. Thus, two nutrient-sensitive stages displaying unique features promote isoflurane-induced inhibition of translation initiation. The rapid phase is GCN-independent and apparently has not been recognized previously. The maintenance phase is GCN-dependent and requires inhibition of general translation imparted by enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation. Surprisingly, as shown here, the transcription activator Gcn4p does not affect anesthetic response.

INTRODUCTION

The use of general anesthesia is fundamental to the practice of modern medicine. In addition to their well-known ability to anesthetize mammals, volatile anesthetics induce effects in all cells and tissues examined, including a wide array of mammalian neuronal and nonneuronal cells, plant cells, yeast, and bacteria (Overton, 1901; Keil et al., 1996; Batai et al., 1999). However, both the sites (the cellular components with which anesthetics directly interact) and the mechanisms of action (the cellular response pathways) responsible for the effects of these clinically essential drugs remain largely unknown.

We are taking a molecular genetic approach to investigate the cellular basis of anesthetic action using the yeast S. cerevisiae. Although yeast are less sensitive to anesthetics than mammals (Keil et al., 1996), we find these drugs inhibit yeast cell division in a manner that remarkably parallels their actions as anesthetics (Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1998; Koblin, 2000). These parallels include the following: correlation of lipophilicity and potency (the Meyer-Overton rule; Koblin, 2000), rapid and reversible effects, a sharp dose-response curve, additivity of partial doses of different anesthetics, and lack of effect in yeast of volatile lipophilic compounds that are nonanesthetic in mammals (nonimmobilizers). These similarities suggest the sites and/or mechanisms responsible for yeast growth arrest and mammalian anesthesia may be closely related.

Previous studies from our laboratory show altered availability of amino acids, in particular leucine or tryptophan, from the external environment plays a key role in the ability of the volatile anesthetic isoflurane to inhibit cell division (Palmer et al., 2002). Numerous, mutually supportive findings provide evidence for this conclusion: deletion or overexpression of amino acid permeases that transport leucine and/or tryptophan alter anesthetic response in strains auxotrophic for these amino acids; strains prototrophic for leucine and tryptophan are more resistant to isoflurane than auxotrophic strains; increased concentrations of leucine and tryptophan in the growth medium render the auxotrophic strains resistant to volatile anesthetics, whereas decreased concentrations of these amino acids make the strains hypersensitive; and uptake of radiolabeled leucine or tryptophan is inhibited by anesthetic exposure. These findings are consistent with models proposing that anesthetics have a physiologically important effect on availability of at least some amino acids by inhibiting activity of their permeases (Palmer et al., 2002).

In yeast, amino acid starvation triggers the general amino acid control (GCN) response, an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that inhibits translation initiation of almost all mRNAs in yeast but increases transcription of numerous amino acid biosynthetic genes (for reviews see Hinnebusch and Natarajan, 2002; Jefferson and Kimball, 2003). Here, we report that although the GCN pathway plays a role in the activity of volatile anesthetics in yeast, another pathway also plays a role in the inhibition of translation initiation. Characterization of the spontaneous isoflurane-resistant zzz3-1 mutant showed ZZZ3 is identical to GCN3. This nonessential gene encodes a component of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B (eIF2B). This complex catalyzes a GDP/GTP exchange reaction on eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) that is required for reutilization of eIF2 in translation initiation (Hershey, 1991; Cigan et al., 1993). Gcn3p is required for regulation of eIF2B activity when eIF2 is phosphorylated (Cigan et al., 1993; Dever et al., 1993). We find isoflurane induces phosphorylation of the α subunit of eIF2 (eIF2α) in wild-type cells but only after extended incubation. In contrast, translation initiation is rapidly inhibited by isoflurane before the GCN-mediated hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α. Thus, the GCN pathway is required for maintenance of this inhibition but the immediate arrest of translation initiation is independent of GCN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and DNA Manipulations

Yeast strains used in this study are derivatives of our reference wild-type strain RLK88-3C (Lin and Keil, 1991) and are listed in Table 1. Strain P754 contains the zzz1Δ-0 mutation (Wolfe et al., 1999), except URA3 and one copy of hisG were deleted from the hisG-URA3-hisG fragment by homologous recombination (Alani et al., 1987). Unless otherwise noted, yeast (Lin and Keil, 1991) and bacterial (Sambrook et al., 1989) media were prepared as previously described.

Table 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| RLK88-3C | MATahis4-260 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 ade2-1 trp1-HIII lys2ΔBX can1R | Lin and Keil (1991) |

| P491 | zzz2-1 zzz3-1 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P615 | zzz3-1 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P754 | MATα his4-260 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 ade2-1 trp1-HIII lys2ΔBX can1R zzz1Δ-0 | This study |

| P1023 | gcn3Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1026 | gcn4Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1417 | HIS4 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1480 | HIS4 LEU2 URA3 ADE2 TRP1 LYS2 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1835 | gcn1Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1837 | gcn2Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1883 | sui2Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP [YCpSUI2 [LEU2]] in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1983 | sui2Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP [YCpSUI2-S51A [LEU2]] in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P1986 | sui2Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP [YCpSUI2-L84F [LEU2]] in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P2289 | gcn20Δ::URA3 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P2467 | zzz2-2 zzz3-1 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| P2330 | gcn1Δ::loxP-kanMX-loxP gcn20Δ::URA3 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| CJP4-1B | zzz2-1 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| CJP22-1D | zzz3-1 in P1417 | This study |

| CJP32-2C | zzz2-2 in RLK88-3C | This study |

| CJP128 | gcn3::LEU2 in RLK88-3C | This study |

PCR reagents as well as restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from various sources and used according to instructions from the manufacturers. Plasmids were propagated in E. coli strain MC1066 (leuB trpC pyrF::Tn5 [Kanr] araT lacX74 del strA hsdR hsdM; obtained from M. Casadaban). Standard procedures for the purification of plasmid (Sambrook et al., 1989) and yeast (Rose et al., 1990) DNA were used. Southern hybridizations were performed as described previously (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Plasmids p1097, p1098, and p1350 (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1993), p919 (Dever et al., 1992), p180 (Hinnebusch, 1985), p227 (Williams et al., 1989), p27-1 (Wek et al., 1992), and p1751 (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1995) were kindly provided by A. G. Hinnebusch and T. E. Dever, and plasmid p299 (Wek et al., 1995) was kindly provided by R. C. Wek. These plasmids have been described previously.

Table 2.

Plasmids

| Plasmid name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pL2461 | YCpZZZ3 | This study |

| pL2696 | YCpgcn3::LEU2 | This study |

| p27-1 | YEpglc7Δ209-312 | A. Hinnebusch |

| p180a | YCpGCN4-lacZ with uORFs | A. Hinnebusch |

| p227 | YCpGCN4-lacZ without uORFs | A. Hinnebusch |

| p299 | YCpgcn2-m2 [URA3]b | R. Wek |

| p919 | YCpSUI2 [URA3] | A. Hinnebusch |

| p1097 | YCpSUI2 [LEU2] | A. Hinnebusch |

| p1098 | YCpSUI2-S51A [LEU2] | A. Hinnebusch |

| p1350 | YCpSUI2-L84F [LEU2] | A. Hinnebusch |

| p1751 | YCpgcn20-Δ1 | A. Hinnebusch |

Plasmid p180 encodes GCN4-lacZ with the four upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in the 5′ noncoding region of GCN4. Plasmid p227 encodes GCN4-lacZ with mutations destroying the function of all four uORFs of GCN4

The gene in the brackets denotes the selectable marker on the plasmid

Plasmid pL2461 contains a 14.4-kb fragment of yeast genomic DNA from chromosome XI that includes ZZZ3. This fragment is inserted in the BamHI site of YCp50 (Rose et al., 1987). Oligonucleotides 0–73 and 0–74 (Table 3), which hybridize to plasmid sequences flanking the insert, were used to sequence into the insert from both ends. DNA sequencing was performed in the Molecular Genetics Core Facility of the M. S. Hershey College of Medicine using an ABI 377 DNA Sequencer.

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 0-1 | 5′-ATTTTAAAAGTCCTACGTATACCAGAAATCGAGAGGAAGGCAGGTCGACAACCCTTAAT-3′ |

| 0-2 | 5′-TTCTATTAAGTCATTGCGTGCATATATTATGTGATTTTTTGTGGATCTGATATCACCTA-3′ |

| 0-73 | 5′-GCCAGCAACCGCACC-3′ |

| 0-74 | 5′-GCCACTATCGACTAC-3′ |

| 0-401 | 5′-ACAAACAAAGCTCTGACTGACACCAATAACTCCTACAGTGCAGGTCGACAACCCTTAAT-3′ |

| 0-402 | 5′-TCAAATACAAAAAGTAACGAGGTTACCACATTGAATTTTCGTGGATCTGATATCACCTA-3′ |

| 0-403 | 5′-TTGGAAAGCCTCGTTGTCTTTTAAGATTTTATAAGCATTGCAGGTCGACAACCCTTAAT-3′ |

| 0-404 | 5′-ACATTGTATATACTTTACCTTTAACTGATGCGTTATAGCGGTGGATCTGATATCACCTA-3′ |

| 0-433 | 5′-TAGGTCATTAAAGAGTAAAGTGCAATCTGTTTACTAATCACAGGTCGACAACCCTAAAT-3′ |

| 0-434 | 5′-TTGCAAAGAATATGATATGGCAGGATATACGTATTTGTTCGTGGATCTGATATCACCTA-3′ |

To localize sequences encoding ZZZ3, deletion derivatives of pL2461 were constructed by digestion with convenient restriction enzymes. The restricted DNA was religated to produce plasmids with various deletions. Plasmid pL2461 was digested at the unique AflII site within GCN3 and treated with the Klenow fragment to make the DNA blunt-ended, and a NotI linker was inserted. The resulting plasmid, pL2655, was digested with NotI, and a 2.0-kb fragment containing the LEU2 gene on a NotI fragment was inserted to produce pL2696.

Gene Deletions

The entire protein-coding sequence of GCN1, GCN2, or GCN3 was deleted from RLK88-3C and replaced with loxP-kanMX-loxP from pUG6 (Guldener et al., 1996) by using appropriate PCR-generated gene disruption cassettes. Oligonucleotides (Table 3) used to generate these cassettes were as follows: GCN1, 0–401 and 0–402; GCN2, 0–403 and 0–404; and GCN3, 0–1 and 0–2. To delete GCN20 in wild-type and gcn1Δ strains, RLK88-3C and P1835 were transformed with the ∼7-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment of p1751 (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1995) and Ura+ transformants were isolated. Plasmid p1751 contains a derivative of GCN20 in which the amino-terminal half of the gene has been replaced with URA3 flanked by direct repeats of hisG (Alani et al., 1987), destroying the complementing activity of the gene (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1995). Correct deletion of GCN1, GCN2, GCN3, or GCN20 was verified by PCR and by increased sensitivity of transformants to sulfometuron methyl (Wek et al., 1995).

To delete the chromosomal copy of the essential SUI2 gene, RLK88-3C was first transformed with a URA3-marked pRS316 vector (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) containing wild-type SUI2 (Table 2: p919; YCpSUI2 [URA3]). The chromosomal copy of SUI2 was deleted from this transformant using a PCR-generated gene-disruption cassette created with oligonucleotides 0–433 and 0–434 (Table 3). Transformants containing a correct deletion of the chromosomal SUI2 gene were verified by PCR. This strain was transformed with LEU2-marked plasmids encoding wild-type (p1097; YCpSUI2 [LEU2]) or mutant versions of SUI2 (p1098; YCpSUI2-S51A [LEU2] or p1350; YCpSUI2-L84F [LEU2]). Transformants were replica plated to SC-leu medium containing 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA) to select cells that lost YCpSUI2 [URA3].

Drug Exposure and Western Blot Analysis

Isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and halothane without thymol as a preservative (kindly provided by Halocarbon, River Edge, NJ) were used for these studies. Isoflurane exposure of yeast grown on solid media was performed as described previously (Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1999). To assay effects of isoflurane, halothane, or 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) exposure in liquid culture, appropriate strains were grown to an OD600 between 0.1 and 0.4 in liquid SC or SC-his medium (Palmer et al., 2002). For anesthetic exposure, 50- or 100-ml aliquots of culture were injected into 250-ml evacuated bottles (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) containing the desired concentration of volatilized anesthetic. Air was admitted into the bottles to achieve 1 atmosphere of pressure. For 3-AT exposure, cell aliquots were supplemented with 3-AT to a final concentration of 100 mM. After various lengths of drug exposure, cells were chilled on ice for 10 min in the presence of 10 mM NaN3 and 10 mM NaF and then harvested by centrifugation.

To prepare cell extracts for Western blot analysis, harvested cells were resuspended in extraction buffer (8 M urea, 5% SDS, 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol) containing protease inhibitors (0.6 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.02 μg/ml pepstatin, 0.05 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.2 μg/ml E-64), incubated at 70°C for 10 min, and then lysed by vigorous vortexing with glass beads (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 425–600 μm). Unbroken cells and debris were removed by centrifugation. Protein concentrations of the extracts were determined by Peterson's modification of the Lowry assay (Peterson, 1977). Aliquots containing 10 μg of total protein were mixed with SDS-containing sample buffer, denatured at 100°C for 5 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Separated proteins were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Membranes were incubated with polyclonal rabbit antibodies that recognize total eIF2α (kindly provided by R. Wek) or eIF2α phosphorylated at serine-51 (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For signal detection, the Supersignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Pierce) was used. Relative levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were quantified using the GeneGnome Chemiluminescence Documentation and Analysis System with GeneTools software (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Polysome Analysis

Cultures of appropriate strains were inoculated into bottles with or without volatilized isoflurane as described above and incubated for various lengths of time. Cycloheximide was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml and the cells were poured over crushed ice to rapidly cool the cultures. Harvesting of cells and preparation of lysates were conducted as described (Gelperin et al., 2002). Eleven milliliters of 10–50% sucrose gradients were prepared by alternatively adding and freezing (in liquid nitrogen) 2.2-ml aliquots of 50, 40, 30, 20, and 10% stock sucrose solutions (M. P. Ashe, personal communication) in buffer (Gelperin et al., 2002). Gradients were thawed overnight at 4°C. Two A260 units of lysates were layered on top and the gradients were centrifuged at 4°C in a SW41 rotor at 35,000 rpm for 160 min (Arava et al., 2003). The gradients were fractionated on an ISCO Density Gradient Fractionator with continuous monitoring by a UV detector (254 nm) set at a sensitivity of 0.5.

Gcn4p-LacZ Enzyme Assay

To assay β-galactosidase enzyme activity, triplicate 1-ml aliquots of cells exposed for 4 h to isoflurane or 3-AT as described above were harvested by centrifugation and washed with 1 ml of Z buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4). Washed cells were resuspended in 0.15 ml of Z buffer containing 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2.8 M chloroform, and 0.3 mM SDS and vortexed for 15 min. β-galactosidase reactions were initiated by the addition of 0.7 ml of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG; 1 mg/ml in Z buffer containing 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Reactions were incubated for 30–60 min at 30°C and terminated by the addition of 0.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3. The A420 of each sample was obtained following clarification by centrifugation. All values are reported in Miller units (Guarente, 1983).

RESULTS

Cloning ZZZ3

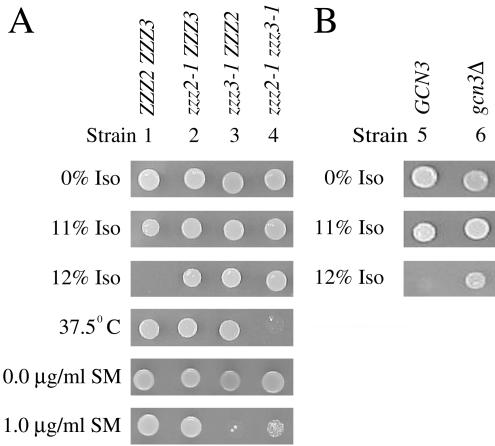

Although most spontaneous isoflurane-resistant (IsoR) mutants we isolated are also temperature sensitive, three of them, M2, M5, and M8, are temperature resistant. Analysis of backcrosses of these mutants to wild-type demonstrated that in each case, the isoflurane resistance is recessive and segregates as a single nuclear gene. All three of these mutants complement the isoflurane resistance of the other recessive zzz mutants that we have characterized (Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1999), indicating they define one or more new genes involved in normal yeast anesthetic response. Complementation analysis among the M2, M5, and M8 mutants suggested M2 and M8 contain mutations in the same gene, whereas M5 contains a mutation in a different gene. Tetrad analysis of crosses among the three mutants confirmed these conclusions. The mutations in M2 and M8 are called zzz2-1 and zzz2-2, respectively, and the mutation in M5 is called zzz3-1. Although neither zzz2-1 nor zzz3-1 strains are temperature sensitive, one quarter of the spores derived from zzz2-1/ZZZ2 zzz3-1/ZZZ3 diploids failed to grow at high temperature (Figure 1A, strain 4). The temperature-sensitive spores were isoflurane resistant and were shown to be zzz2-1 zzz3-1 double mutants. The synthetic temperature sensitivity of these double mutants is recessive.

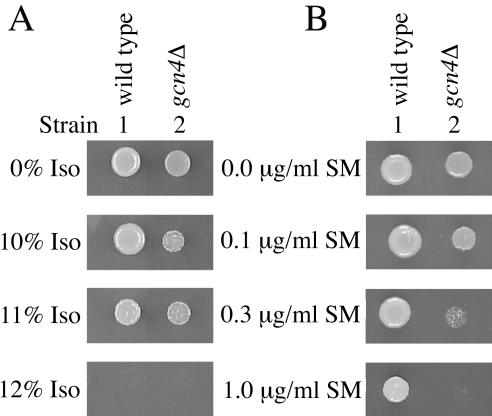

Figure 1.

Anesthetic and high-temperature response of zzz2 and zzz3(gcn3) mutants. Approximately 5 × 103 cells of the indicated strains were spotted on SC medium and incubated for 3 d at 30°C in the presence of various concentrations of isoflurane (Iso) or in the absence of isoflurane at 37.5°C. ZZZ2 ZZZ3 and GCN3 are alternative names for the RLK88-3C wild-type strain. (A) Growth of the zzz2-1 zzz3-1 double mutant is temperature sensitive and isoflurane resistant. (B) Deletion of GCN3 (gcn3Δ) renders cells resistant to isoflurane.

The temperature sensitivity of zzz2-1 zzz3-1 double mutants provided a convenient means for cloning the ZZZ2 and ZZZ3 genes. DNA from a YCpURA3 yeast genomic library was transformed into the P491 double (zzz2-1 zzz3-1) mutant and 21 Ura+ transformants that grew at 37.5°C were isolated. Plasmid DNA was prepared from each of the temperature-resistant transformants and introduced into 1) naïve P491, 2) a zzz2-1 single-mutant strain (CJP4-1B), and 3) a zzz3-1 single-mutant strain (CJP22-1D). All 21 plasmids conferred temperature resistance to the naïve P491, but the transformants were still IsoR. One of the 21 plasmids restored isoflurane sensitivity to the zzz2-1 strain but not to the zzz3-1 strain, suggesting it contains the ZZZ2 gene (characterization of this gene and its role in anesthetic response will be described elsewhere). Ten of the plasmids restored isoflurane sensitivity to the zzz3-1 strain but not to the zzz2-1 strain, suggesting these contain the ZZZ3 gene. Ten of the plasmids failed to restore isoflurane sensitivity to either single mutant, suggesting they contain second-site suppressors of the temperature sensitivity of zzz2-1 zzz3-1 double mutants.

PstI digestion of the putative ZZZ3-containing plasmids showed all the inserts contained 2.0- and 0.8-kb PstI fragments, indicating that these inserts are overlapping subclones. Sequencing into both ends of the insert in one of these plasmids, pL2461, revealed that it contained a 14.4-kb fragment from chromosome XI containing the carboxy-terminus of YKR020W, full-length YKR021W, YKR022C, YKR023W, DBP7, RPC37, GCN3, and tRNA-arginine genes, and the amino-terminal portion of YKR027W. Deletion analysis was used to further localize the sequences in pL2461 that complement the zzz3 phenotype. Removal of the AflII-AatII fragment that removes the amino-terminal portions of both GCN3 and YKR027W abolished the complementing activity of pL2461. To determine which of these two genes was responsible for the complementing activity of pL2461, LEU2 was inserted at the unique AflII site within GCN3. This insertion abolished the complementing activity of the plasmid, indicating the complementing gene is GCN3.

ZZZ3 Is Identical to GCN3

If ZZZ3 is GCN3, the zzz3-1 mutant is expected to be hypersensitive to drugs, such as sulfometuron methyl, that induce amino acid starvation. This is indeed the case (Figure 1A, compare strains 3 and 1). The zzz2-1 mutation diminishes the sensitivity of zzz3-1 to this drug (Figure 1A, compare strains 4 and 3), an effect that remains unexplained. To determine genetically whether GCN3 is ZZZ3 or a second-site suppressor of zzz3 mutations, plasmid pL2692 containing the gcn3::LEU2 disruption was digested with PstI and transformed into RLK88-3C. Leu+ transformants were isolated, and proper insertion of the gcn3::LEU2 disruption allele on the chromosome was verified by Southern analysis. All strains containing the gcn3::LEU2 disruption were resistant to isoflurane. In addition, they were cross-resistant to the four other volatile anesthetics (halothane, methoxyflurane, sevoflurane, and enflurane) tested (unpublished data). All spores from tetrads derived from a cross between one of the disruptants, CJP128, and a zzz3-1 haploid were isoflurane resistant, indicating ZZZ3 is identical to GCN3. Cells containing a precise deletion of the protein-encoding sequence of GCN3 were also isoflurane resistant (Figure 1B, compare strains 6 and 5), indicating loss of Gcn3p function produces altered anesthetic response. Finding that deletion of GCN3 renders cells resistant to volatile anesthetics suggests the general amino acid control pathway is involved in anesthetic response.

The GCN pathway is a nutrient-sensing pathway in yeast that responds to nutrient limitation by activating transcription of a variety of genes including amino acid biosynthetic genes and some amino-acyl-tRNA synthetase genes (Natarajan et al., 2001), leading to increased production of amino acids and charged tRNAs. This pathway is activated during starvation when eIF2 is phosphorylated on serine-51 of its α subunit, impeding a GDP/GTP exchange reaction catalyzed by eIF2B that is required to recycle eIF2 to an active (GTP-bound) form that functions in translation initiation. This leads to an overall decrease in translation, but specifically stimulates production of Gcn4p, a transcriptional activator of amino acid biosynthetic genes. Amino acid starvation also induces phosphorylation of eIF2α by an evolutionarily conserved enzyme in mammalian systems (Zhang et al., 2002).

GCN3 encodes the nonessential α subunit of the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B. Gcn3p is required for inhibition of eIF2B activity in response to eIF2α phosphorylation but not for catalytic activity of eIF2B (Cigan et al., 1993; Dever et al., 1993). Deletion of GCN3 has been shown to alleviate growth inhibition associated with high levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in yeast (Dever et al., 1993). This suggests the growth-inhibitory phenotype associated with anesthetic exposure may result from increased phosphorylation of eIF2α and that deletion of GCN3 overcomes this inhibition, allowing cells to divide in the presence of anesthetics.

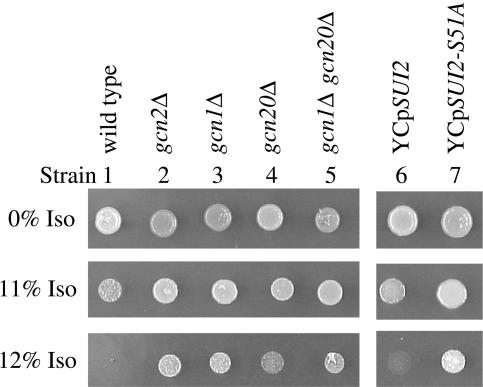

Mutations Affecting eIF2α Phosphorylation Enhance Volatile Anesthetic Resistance

To further characterize the role of the GCN pathway in anesthetic response, we compared the isoflurane minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC; Keil et al., 1996) of several gcn mutants to wild-type (the isoflurane MIC of the wild-type strain is 12%; Keil et al., 1996). GCN2 encodes the protein kinase that phosphorylates serine-51 of eIF2α in response to amino acid starvation in yeast (Dever et al., 1992). If increased phosphorylation of eIF2α arrests cell division during isoflurane exposure, deletion of this kinase should render cells anesthetic resistant. We find gcn2Δ strains are indeed more resistant to isoflurane than an isogenic wild-type strain (Figure 2, compare strains 2 and 1), providing further evidence that the general control pathway plays a critical role in anesthetic response.

Figure 2.

Mutations affecting eIF2α phosphorylation increase resistance to isoflurane. Cells were spotted and incubated as described in the legend for Figure 1. Mutants in the left-hand panel contain precise deletions of the protein-encoding sequences of the indicated genes. Single-copy plasmids containing wild-type (YCpSUI2) or mutant (YCpSUI2-S51A) SUI2 genes were tested for anesthetic response in a sui2Δ strain background (right-hand panel). The SUI2 gene encodes the eIF2α protein. The eIF2α produced by the SUI2-S51A mutant cannot be phosphorylated on Ser-51 because of mutation of this residue to alanine.

Activation of the GCN response during amino acid starvation in yeast is proposed to require binding of uncharged tRNA to a region of Gcn2p homologous to histidyl-tRNA synthetase (Wek et al., 1989). To examine whether uncharged tRNAs signal activation of the GCN response during anesthetic exposure, we tested the isoflurane response of the gcn2-m2 mutation that reduces binding of uncharged tRNAs (Wek et al., 1995). Gcn2Δ cells containing this mutant allele on a single-copy plasmid (YCpgcn2-m2) are as resistant to isoflurane as the gcn2Δ strain transformed with the control YCp plasmid (unpublished data). In contrast, introduction of a YCpGCN2 plasmid into this strain restores normal sensitivity to the anesthetic. This suggests that during anesthetic exposure uncharged tRNAs activate the growth inhibitory GCN pathway and that the partial inhibition of amino acid import induced by anesthetics (Palmer et al., 2002) produces amino acid limitation.

GCN1 and GCN20 encode subunits of a protein complex required for activation of Gcn2p kinase activity during amino acid starvation (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1995) and deletion of either GCN1 or GCN20 reduces phosphorylation of eIF2α (Marton et al., 1993; Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1995). In contrast, only Gcn1p is involved in induction of the general control response during glucose limitation (Yang et al., 2000). The role of GCN1 and GCN20 in anesthetic response was tested. We find gcn1Δ strains show a level of isoflurane resistance similar to gcn2Δ strains (Figure 2, compare strain 3 to strains 1 and 2). Although gcn20Δ strains are resistant to isoflurane (Figure 2, compare strains 4 and 1), they grow less in 12% isoflurane than gcn1Δ or gcn2Δ strains (Figure 2, compare strain 4 with strains 2 and 3). Analysis of a double gcn1Δ gcn20Δ mutant showed gcn1Δ is epistatic to gcn20Δ with respect to anesthetic response (Figure 2, compare strain 5 to strains 3 and 4), suggesting these gene products participate in the same pathway (Game and Cox, 1972, 1973).

Finding that deletion of GCN1, GCN2, or GCN20, all of which are involved in phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine-51, renders cells resistant to isoflurane suggests a mutant eIF2α that cannot be phosphorylated at this residue should also be anesthetic resistant. The chromosomal SUI2 gene, which encodes eIF2α, was deleted and YCp plasmids expressing either wild-type eIF2α (SUI2) or a mutant eIF2α that cannot be phosphorylated on serine-51 due to mutation of this residue to alanine (SUI2-S51A) were introduced. Cells containing the SUI2-S51A mutation were resistant to isoflurane compared with cells transformed with wild-type SUI2 (Figure 2, compare strains 7 and 6). We tested whether the critical feature for growth inhibition is phosphorylation of serine-51 or the effect of this phosphorylation on GDP/GTP exchange. In the SUI2-L84F mutant, phosphorylation of serine-51 still occurred but the L84F mutation is thought to diminish the inhibitory effects of this phosphorylation on GDP/GTP exchange (Vazquez de Aldana et al., 1993). Sui2Δ cells containing a single-copy plasmid encoding SUI2-L84F were more resistant to isoflurane than control SUI2 cells (unpublished data), indicating inhibition of GDP/GTP exchange is critical for anesthetic response. This suggestion is consistent with finding gcn3Δ mutants are isoflurane resistant because gcn3Δ mutants permit GDP/GTP exchange even when eIF2α is phosphorylated (Dever et al., 1993). Taken together, these results indicate phosphorylation on serine-51 of eIF2α plays a key role in the normal anesthetic response of yeast by inhibiting the GDP/GTP exchange reaction required for reutilization of eIF2 in translation initiation.

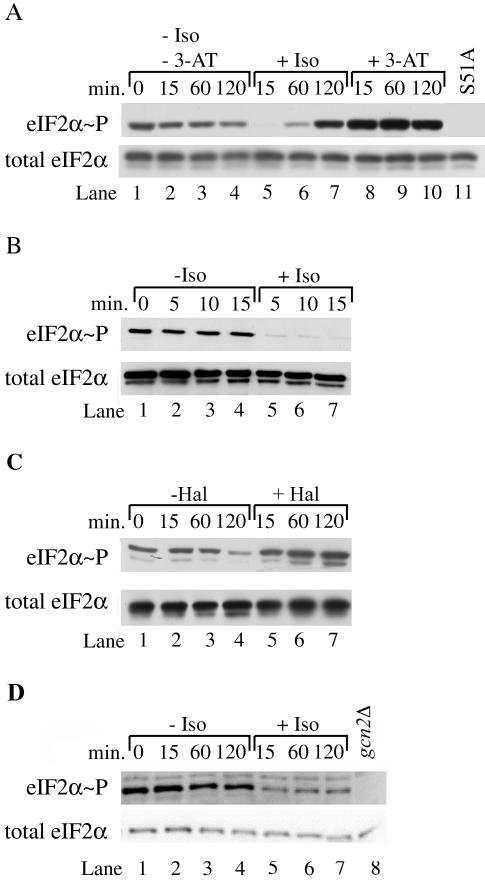

Isoflurane Affects the Level of eIF2α Phosphorylation

Our genetic results show components of the GCN pathway involved in phosphorylation of eIF2α are important in the response of yeast cells to volatile anesthetics. To directly test whether anesthetic-induced growth inhibition is due to increased eIF2α phosphorylation and activation of the GCN pathway, we performed immunoblot analysis using a polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes eIF2α phosphorylated on serine-51. Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α increased approximately fivefold after 120 min of isoflurane exposure (Figure 3A, compare lane 7 with lane 4). However, within the first 15 min of isoflurane exposure, levels of phosphorylated eIF2α decreased ∼15-fold (Figure 3A, compare lane 5 with lane 2). Because amino acid uptake and cell growth are inhibited within this 15 min (Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1998; Palmer et al., 2002), finding decreased phosphorylation of eIF2α was unexpected. Examination of extracts from cells exposed for even shorter times showed phosphorylated eIF2α decreased fivefold within the first 5 min (Figure 3B, compare lane 5 with lane 2). Thus, the response of yeast to isoflurane is very rapid. It seems unlikely that decreased phosphorylation of eIF2α is an uncharacterized mechanism for growth inhibition, because both gcn2Δ and SUI2-S51A mutants, which are not phosphorylated on residue 51 (unpublished data and Figure 3A, lane 11, respectively), are resistant to isoflurane (Figure 2, strains 2 and 7).

Figure 3.

Isoflurane exposure affects eIF2α phosphorylation. (A) A logarithmically growing culture of P1417 was split and grown in the absence or presence of isoflurane (Iso) or 100 mM 3-amino triazole (3-AT) for various lengths of time. At the indicated times, cells were harvested. Extracts were prepared and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Blots were probed with antibodies recognizing either total eIF2α or eIF2α phosphorylated at serine-51 (eIF2α∼P). An extract derived from a mutant (P1983) that cannot be phosphorylated at serine-51 because of mutation of the serine to alanine (S51A) is shown as a control. (B) Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α decrease rapidly during isoflurane exposure. Cells from a logarithmically growing culture of RLK88-3C were exposed to isoflurane as described for 5–15 min. Extracts were prepared and fractionated by SDS-PAGE as described. (C) Halothane exposure does not induce the rapid reduction in levels of phosphorylated eIF2α. A logarithmically growing culture of RLK88-3C was split and grown in the presence or absence of halothane for various lengths of time. At the indicated times, cells were harvested and extracts were treated as described above. (D) Exposure of a prototroph to isoflurane produces a rapid reduction of levels of phosphorylated eIF2α that do not recover. A logarithmically growing culture of P1480 was split and grown in the presence or absence of isoflurane. At appropriate times, cells were harvested and extracts were treated as described above. A similar extract prepared from the gcn2Δ mutant P1837 that cannot phosphorylate eIF2α is included as a control.

The initial decrease in phosphorylated eIF2α in response to isoflurane exposure contrasts with the response observed in cells exposed to the histidine biosynthetic inhibitor, 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). Exposure to 3-AT produced maximal phosphorylation of eIF2α within 15 min (Figure 3A, compare lane 8 with lane 2), indicating rapid activation of the GCN pathway. Taken together, these results demonstrate the GCN pathway is affected by volatile anesthetic exposure, but it seems unlikely this nutrient-sensing pathway is responsible for the initial, rapid growth inhibition caused by isoflurane. Instead, the GCN pathway may be involved in long-term maintenance of growth inhibition induced by this volatile agent.

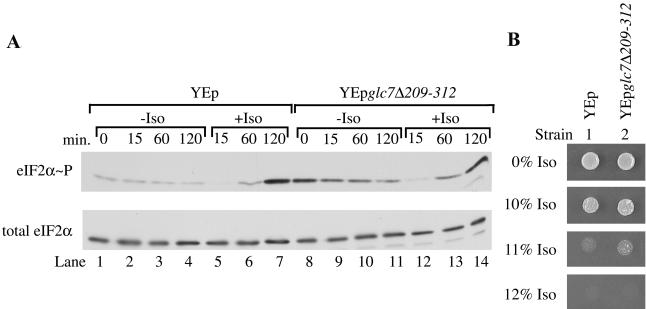

GLC7 Does not Play a Major Role in Isoflurane-induced Dephosphorylation of eIF2α

Activation of a phosphatase is one potential explanation for the rapid decrease in eIF2α phosphorylation elicited by isoflurane exposure. The type 1 protein phosphatase Glc7p has previously been implicated in modulation of eIF2α dephosphorylation in yeast. A truncation mutation of this essential gene, encoded by glc7Δ209–312, exerts a dominant negative phenotype when overexpressed, leading to reduced Glc7p phosphatase activity and increased phosphorylation of eIF2α (Wek et al., 1992). To determine whether Glc7p plays a role in the phosphatase activity associated with isoflurane exposure, the level of phosphorylated eIF2α during incubation with isoflurane was compared in a strain overexpressing the truncated GLC7 allele (YEpglc7Δ209-312) and a strain containing the vector control (YEp). As expected, in the absence of isoflurane the strain overexpressing glc7Δ209-312 exhibited higher basal levels of phosphorylated eIF2α than the strain containing the vector control (Figure 4A, compare lanes 8–11 with lanes 1–4). During the first 15 min of isoflurane exposure, phosphorylation of eIF2α still dramatically decreased in cells overexpressing the GLC7 truncation (Figure 4A, compare lane 12 with lane 9). Overexpression of this mutant form also did not alter the isoflurane MIC of RLK88-3C (Figure 4B, compare strains 2 and 1). These negative results must be interpreted cautiously, but they do not indicate that the phosphatase encoded by GLC7 plays a major role in the dephosphorylation of eIF2α induced by isoflurane exposure.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of a dominant negative GLC7 mutation (YEpglc7Δ209-312) does not affect the isoflurane-induced decrease of phosphorylated eIF2α. (A) Logarithmically growing cultures of RLK88-3C containing the indicated plasmids were split and grown in the presence or absence of isoflurane (Iso) for various lengths of time. At the indicated times, cells were harvested. Extracts were prepared and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. The blot was probed with antibodies recognizing total eIF2α or eIF2α phosphorylated at serine-51 (eIF2α∼P). (B) Overexpression of the dominant negative GLC7 truncation does not alter anesthetic response. Approximately 5 × 103 cells from cultures of RLK88-3C transformed with the indicated plasmids were spotted on SC-ura medium and tested for response to isoflurane (Iso).

Not All Anesthetics Induce Dephosphorylation of eIF2α

The rapid decline in phosphorylation of eIF2α induced by isoflurane is not a general feature of volatile anesthetic exposure. Exposure to the volatile anesthetic halothane does not reduce eIF2α phosphorylation after a brief exposure (Figure 3C, compare lane 5 with lane 2). Rather, the level of phosphorylation is relatively stable after 15 min and then increases upon longer exposure (Figure 3C, lanes 5–7). Similar results were observed when wild-type cells were exposed to the volatile anesthetic methoxyflurane (unpublished data). These results suggest that although eIF2α phosphorylation increases after long-term exposure to volatile anesthetics, the initial response of cells to different anesthetics varies.

Expression of GCN4 Is Induced by Isoflurane Exposure

Gcn4p is a transcriptional activator of a wide range of genes, including many involved in amino acid biosynthesis. Regulation of GCN4 translation is mediated by four short upstream open reading frames (uORFs) located in the 5′ leader of GCN4 mRNA (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986). When amino acids are plentiful, the uORFs repress translation of GCN4 mRNA (Hinnebusch, 1984; Abastado et al., 1991). A starvation-induced increase in phosphorylated eIF2α alleviates this repression in yeast, leading to elevated levels of Gcn4p and stimulation of transcription of a wide range of genes including ones encoding amino acid biosynthetic enzymes (Jia et al., 2000; Natarajan et al., 2001).

To determine whether isoflurane stimulates GCN4 expression in yeast, we measured β-galactosidase enzyme activity in cells harboring a plasmid containing a GCN4-lacZ fusion with intact uORFs (plasmid p180; Hinnebusch, 1985). As a control, amino acid starvation induced with 3-AT, which is known to activate GCN4 expression (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986; Yang et al., 2000), was examined. Expression of GCN4-lacZ increased approximately threefold after long-term isoflurane exposure (Table 4), consistent with our observations that anesthetics induce eIF2α phosphorylation. This is similar to the approximate fivefold increase observed when this strain is treated with 3-AT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of drug exposure on GCN4 expression

| β-galactosidase enzyme activitya

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-AT

|

Isoflurane

|

||||

| Plasmid | uORFsb | - | + | - | + |

| p180 | + | 10.3 ± 0.9 | 49.8 ± 7.6 (4.8)c | 15.6 ± 1.0 | 47.5 ± 1.4 (3.0) |

| p227 | - | 131.1 ± 4.1 | 171.9 ± 5.1 (1.3) | 170.1 ± 5.0 | 222.6 ± 2.7 (1.3) |

All values represent the average of at least three independent experiments. Values are reported as the average Miller units ± SEM

The significance of the presence or absence of uORFs is described in the text

The numbers in parentheses represent the fold-increase in GCN4 expression in drug-treated cells

To determine whether the isoflurane-induced increase in GCN4-lacZ expression is regulated by translational or transcriptional control, we measured β-galactosidase activity in cells with a plasmid containing a GCN4-lacZ fusion with mutations in the four uORFs (plasmid p227; Williams et al., 1989). These mutations destroy the ability of the uORFs to regulate translation of the GCN4-lacZ mRNA, and therefore, increased Gcn4-LacZp activity is attributable to transcriptional control (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986; Williams et al., 1989; Yang et al., 2000). With both isoflurane and 3-AT, GCN4-lacZ expression increased only 1.3-fold (Table 4). These results suggest isoflurane induces GCN4 expression at the translational level as is expected if the cells are starving for amino acids. Induction of Gcn4p synthesis is not required for normal anesthetic response, as deletion of GCN4 does not alter the isoflurane MIC of RLK88-3C (Figure 5A, compare strains 2 and 1). As expected, the gcn4Δ mutant is hypersensitive to sulfometuron methyl (Figure 5B, compare strains 2 and 1).

Figure 5.

Deletion of GCN4 (gcn4Δ) does not affect the anesthetic response of RLK88-3C. Cells were spotted and incubated as described in the legend for Figure 1. (A) Although gcn4Δ strains grow more slowly in the absence or presence of isoflurane, this mutation does not affect the isoflurane MIC. (B) As expected, gcn4Δ strains are hypersensitive to sulfometuron methyl (SM).

Isoflurane Induces Two Separate Pathways That Arrest Translation Initiation

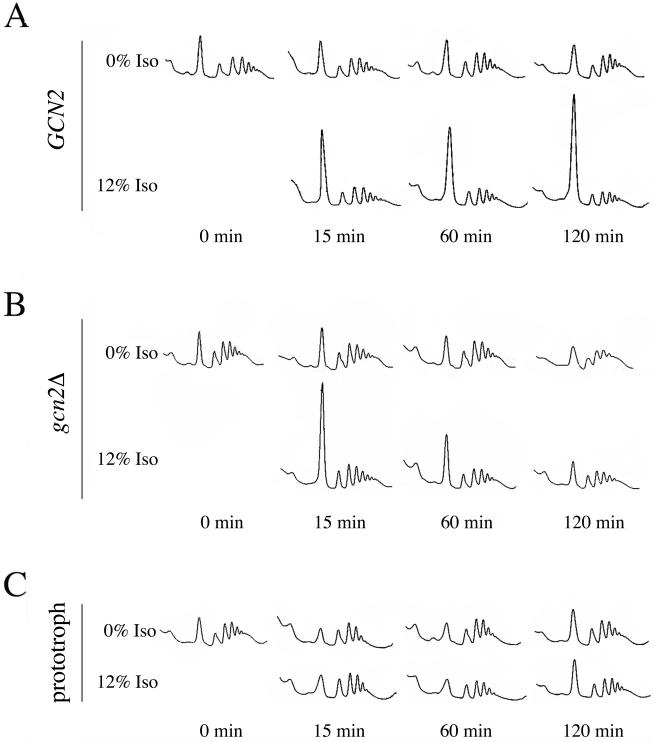

The elevated level of phosphorylated eIF2α observed after 120 min of isoflurane exposure indicates translation initiation should be inhibited after this extended exposure. To examine this prediction, polysome profiles were generated following various lengths of incubation in the presence or absence of isoflurane. In the wild-type strain, RLK88-3C, the level of monosomes was dramatically increased after 120 min of drug exposure and the level of polysomes was reduced (Figure 6A). The accumulation of monosomes indicated translation initiation was inhibited, consistent with the elevated level of phosphorylated eIF2α observed at this time (Figure 3A, compare lane 7 with lane 4).

Figure 6.

A GCN2-dependent and a GCN2-independent pathway are involved in inhibition of translation initiation by isoflurane. Logarithmically growing cultures of various strains were split and incubated in the presence or absence of isofluarane (Iso) for 0, 15, 60, or 120 min before harvesting the cells. Extracts were prepared and polysomes were separated on sucrose gradients. The gradients were fractionated and scanned for UV absorbance at 254 nm. (A) Isoflurane rapidly inhibits translation initiation in RLK88-3C. This inhibition is maintained throughout the length of exposure to the anesthetic. (B) Translation initiation is rapidly inhibited in the gcn2Δ strain P1837 but the inhibition is not maintained. (C) Isoflurane does not inhibit translation in the prototrophic strain P1480.

Inhibition of translation initiation occurred after only 15 min of isoflurane exposure (Figure 6A) despite the fact that phosphorylation of eIF2α was dramatically decreased at that time (Figure 3A, compare lane 5 with lane 2). This indicates that inhibition during early times of exposure is independent of the phosphorylation status of eIF2α. In agreement with this prediction, the rapid inhibition of translation initiation was GCN2 independent, as shown by the dramatic increase in monosomes in a gcn2Δ mutant after 15 min of isoflurane exposure (Figure 6B). However, maintenance of this inhibition was GCN2 dependent as evidenced by the recovery of translation initiation in the gcn2Δ strain during extended isoflurane incubation (60–120 min; Figure 6B).

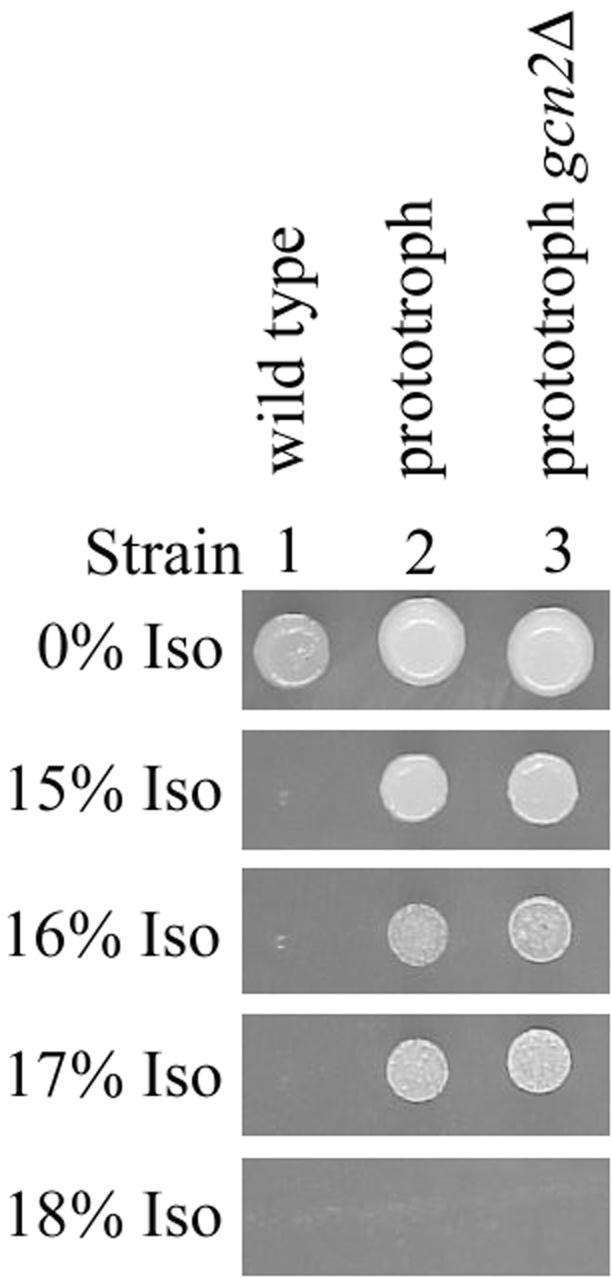

Increased Phosphorylation of eIF2α and Inhibition of Translation Do Not Occur in a Prototrophic Strain

Strains such as RLK88-3C that are auxotrophic for leucine and tryptophan are much more sensitive to isoflurane than strains prototrophic for these amino acids (Palmer et al., 2002) or strains such as P1480, a complete prototroph derived from RLK88-3C (Figure 7, compare strain 2 with strain 1). The effect of exposure to 12% isoflurane on eIF2α phosphorylation and translation initiation was tested in P1480. Hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α did not occur in the prototroph even after 120 min of exposure to the anesthetic (Figure 3D, compare lanes 7 and 4). However, phosphorylation of eIF2α decreased approximately twofold within the first 15 min of exposure and did not recover even during extended exposure (Figure 3D, compare lanes 5–7 with lanes 2–4). Exposure of the prototroph to higher concentrations of isoflurane led to an even greater decrease in the level of phosphorylated eIF2α after both short and long periods of exposure (unpublished data). Thus, the effects of isoflurane on eIF2α phosphorylation involved at least two separate events: 1) a rapid decrease in the level of phosphorylation induced in both auxotrophic and prototrophic strains, and 2) hyperphosphorylation after extended isoflurane exposure that occurred in the RLK88-3C auxotroph but not in a prototroph derived from this strain.

Figure 7.

Response to isoflurane is GCN2-independent in prototrophic strains. Cells were spotted and incubated as described in the legend for Figure 1.

Translation initiation in the prototroph was unaffected after either short or long periods of exposure to 12% isoflurane (Figure 6C). Consistent with the lack of eIF2α hyperphosphorylation and the lack of effect on translation initiation, deletion of GCN2 in this prototroph did not affect the anesthetic response of the prototroph (Figure 7, compare strain 3 with strain 2).

DISCUSSION

Translation Arrest Involves GCN-independent and GCN-dependent Processes

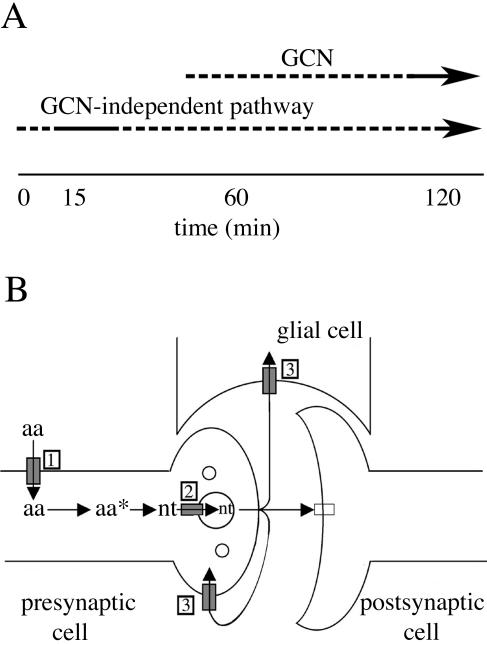

Mutations of several genes in the GCN signaling pathway render yeast resistant to growth inhibition by volatile anesthetics, suggesting a role for this pathway in normal anesthetic response. Because inhibition of cell division by isoflurane occurs rapidly (within 15 min; Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1998), it seemed likely eIF2α hyperphosphorylation would occur quickly, leading to inhibition of translation initiation. Instead, drug exposure produced a rapid decrease in phosphorylated eIF2α. Decreased phosphorylation of eIF2α during isoflurane exposure is not limited to this strain background because it also occurs in the parent strain used in the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project (L. K. Palmer and R. L. Keil, unpublished data; Winzeler et al., 1999; Giaever et al., 2002). Polysome profiles demonstrated an early stage of translation initiation was inhibited during the first 15 min of anesthetic exposure despite decreased eIF2α phosphorylation. This appears to be nutrient sensitive, as inhibition of translation does not occur during this time in a prototrophic strain. These results indicate activation of a GCN-independent nutrient-sensing pathway is responsible for the initial inhibition of translation initiation and cell division by isoflurane (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Models for cellular responses to volatile anesthetics. (A) Inhibition of translation initiation by isoflurane involves both GCN and a GCN-independent pathway. The dashed parts of the lines indicate the uncertainty as to the times at which each pathway is required to produce normal anesthetic response. Growth inhibition occurs within 15 min of exposure (Keil et al., 1996; Wolfe et al., 1998). (B) Transport of amino acids and neurotransmitters in neuronal cells. Volatile anesthetics may induce anesthesia by affecting transport of amino acids and/or neurotransmitters in neuronal cells. When starved for these nutrients, cells may induce nutrient-sensing/deprivation response pathways such as GCN that could produce anesthesia. Three transport processes that may be affected by volatile anesthetics are indicated and described more completely in the text (indicated by the boxed numbers). Filled rectangle, transporter; unfilled rectangle, neurotransmitter receptor; circles, vesicles; aa, amino acid; aa*, metabolic derivative of aa; nt, neurotransmitter.

The pathways responsible for rapid inhibition of initiation remain to be identified. A variety of processes that regulate translation and are at least partially GCN2-independent are potential candidates. These include the following: Ras-dependent activation of protein kinase A that has been implicated in the rapid, transient inhibition of translation observed when cells are shifted from medium rich in amino acids to medium lacking amino acids (Tzamarias et al., 1989; Engelberg et al., 1994); eIF2α phosphorylation-independent alteration of eIF2B activity that plays a role in reduction of translation initiation by fusel alcohols (Ashe et al., 2001); the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway that regulates translation initiation and cell growth in response to nutrient availability (for a review see Lorberg and Hall, 2004); the unconventional prefoldin URI that regulates GCN4 mRNA translation, and potentially global translation, in a nutrient-sensitive manner that is partially independent of GCN2 (Gstaiger et al., 2003); and the eIF4E-binding protein encoded by EAP1 that alters translation initiation during membrane stress (Deloche et al., 2004). Although many of these processes have not been shown to occur transiently, anesthetic exposure may elicit novel facets that constrain the time frame for function of the response.

Hyperphosphorylation of eIF2α after extended anesthetic exposure (60–120 min) is required to sustain inhibition of translation initiation. Combined with the anesthetic-resistance phenotype of gcn1, gcn2, gcn3, and gcn20 mutants, these results indicate long-term maintenance of cell division arrest is GCN dependent (Figure 8A).

GCN Pathway and Anesthetic Response

Although eIF2α hyperphosphorylation is induced by either anesthetic or 3-AT exposure, there are key differences in the response of yeast to these drugs. First, deletion of GCN1, GCN2, GCN3, or GCN20 renders yeast sensitive to 3-AT (Hannig et al., 1990; Dever et al., 1992, 1993; Wek et al., 1995) but resistant to anesthetics. This is reminiscent of increased salt tolerance observed in gcn1, gcn2, or gcn3 mutants (Goossens et al., 2001). Second, although 3-AT rapidly induces maximal eIF2α phosphorylation, anesthetics induce a much slower increase. This longer time frame occurs whether an anesthetic initially produces dephosphorylation of eIF2α (isoflurane) or not (halothane and methoxyflurane). Finally, although expression of GCN4 is induced by both drugs (Mueller and Hinnebusch, 1986; Yang et al., 2000; and these studies), GCN4 does not play a major role in anesthetic response of the wild-type strain because deletion of this gene does not alter the isoflurane MIC. This contrasts with 3-AT exposure, where deletion of GCN4 produces increased sensitivity (Wolfner et al., 1975).

These differences can be attributed to the two outcomes of activation of the GCN pathway in yeast: increased transcription of biosynthetic genes and overall inhibition of translation initiation. For 3-AT, which inhibits histidine biosynthesis in cells prototrophic for histidine, the former outcome is critical, whereas for anesthetics, which affect amino acid availability from medium for auxotrophic cells (Palmer et al., 2002), the latter appears more important. For example, in Gcn+ His+ cells, 3-AT inhibits histidine biosynthesis, leading to increased phosphorylation of eIF2α and thus, inhibition of the GDP/GTP exchange reaction required for efficient translation initiation (Dever et al., 1992). This increases Gcn4p production, and ultimately increases transcription of amino acid biosynthetic genes (Jia et al., 2000; Natarajan et al., 2001). Increased transcription of histidine biosynthetic genes provides these cells a means to grow in the presence of 3-AT because the cells can synthesize histidine. In Gcn- His+ cells (e.g., gcn1, gcn2, gcn3, or gcn20), expression of GCN4 remains repressed during 3-AT exposure because of continued efficient GDP/GTP exchange. As a consequence, the cells cannot increase transcription of histidine biosynthetic genes. Thus, these mutants are hypersensitive to 3-AT.

In contrast, isoflurane-induced GCN4 expression in Gcn+ Leu- Trp- cells does not provide cells with a compensatory mechanism to grow during anesthetic exposure. Because these cells contain auxotrophic mutations, they cannot synthesize leucine or tryptophan regardless of transcription levels. Instead, availability of these nutrients from medium is critical. In most Gcn- Leu- Trp- cells (e.g., gcn1, gcn2, gcn3, or gcn20 strains but not gcn4 strains), GDP/GTP exchange functions efficiently, allowing normal levels of translation and cell growth in the presence of isoflurane. Gcn4 mutants are an exception because Gcn4p functions downstream of the GDP/GTP exchange reaction. Therefore, as in Gcn+ cells, GDP/GTP exchange is inhibited. Thus, for 3-AT, increased transcription of biosynthetic genes is critical, although for anesthetics, repression of global protein synthesis appears key.

How can mutants such as gcn1 be resistant to anesthetics if these drugs inhibit amino acid import? A potential explanation is that import is only partially inhibited. This is consistent with our finding that after 30 min of isoflurane exposure, tryptophan import is only inhibited 60% (Palmer et al., 2002). Presumably, this partial inhibition is sufficient to activate phosphorylation of eIF2α and inhibit translation in a Gcn+ strain, but is not sufficient to actually starve mutants that cannot phosphorylate eIF2α. Thus, it appears the GCN pathway can be triggered before circumstances become extremely dire, as would be expected for a protective response pathway.

Anesthetic-induced Inhibition of Protein Synthesis in Mammalian Cells

Numerous studies in mammalian systems show protein synthesis decreases during anesthetic exposure (e.g., Hammer and Rannels, 1981; Wartell et al., 1981; Rannels et al., 1982, 1983; Flaim et al., 1983). Inhibition is rapid, dose dependent, and reversible and does not result in extensive cell damage or death. Mechanisms mediating anesthetic-induced inhibition of translation in mammals are not defined. Given the extensive parallels between the response of yeast and mammalian cells to anesthetics, our results suggest these drugs may inhibit protein synthesis in mammals in part through the evolutionarily conserved GCN pathway. Preliminary studies indicate eIF2α phosphorylation is induced by anesthetic exposure in mammalian tissues (L. K. Palmer, S. L. Rannels, S. R. Kimball, L. S. Jefferson, and R. L. Keil, unpublished data). Additional characterization of the mechanism is in progress.

Anesthetic Mechanisms of Action: Nutrient (Neurotransmitter)-sensing Signaling Pathways?

The importance of elucidating mechanisms of anesthetic action often seems minimized by interest directed at identification of sites of action. In reality, understanding mechanisms that induce anesthesia or associated side effects may be more important. The pathways involved should provide targets for drug intervention to enhance desirable drug effects or minimize undesirable ones. Our analysis suggests anesthetics inhibit yeast cell division by decreasing availability of particular amino acids (Palmer et al., 2002). In part, induction of the GCN pathway leads to suspension of normal cellular activities and maintenance of growth arrest. Do our findings with yeast provide insight regarding anesthetic mechanisms in mammals? Possibly anesthesia and/or side effects of anesthetics result from induction of the GCN and other nutrient-sensing pathways in response to anesthetic-induced nutrient deprivation. Alternatively, there may be uncharacterized sensing-response pathways specifically triggered by neurotransmitter deprivation. Such pathways may be activated in neuronal cells deprived of basal levels of neurotransmitter input, causing cells to suspend normal activity and enter a special state resulting in anesthesia. Given that 1) amino acids (e.g., glutamate, aspartate, and glycine) and their derivatives (e.g., GABA, serotonin, catecholamines, histamine, and nitric oxide) are neurotransmitters; 2) amino acids (e.g., leucine) play a key role in neurotransmitter metabolism (Yudkoff et al., 1994, 1997); and 3) volatile anesthetics affect transport of amino acids (Shimada et al., 1995) and neurotransmitters (Martin et al., 1990; el-Maghrabi and Eckenhoff, 1993; Larsen and Langmoen, 1998; Sugimura et al., 2001) in mammals, these are reasonable possibilities. Transport of amino acids and their derivatives plays critical roles in transmitter synthesis and nerve transmission (Figure 8B). These include 1) transport of amino acids into neurons where they may act as neurotransmitters or be metabolized to produce neurotransmitters; 2) transport of neurotransmitters into synaptic vesicles; and 3) reuptake, which entails transport of released transmitters from synapses into neural or glial cells and plays a major role in neurotransmitter inactivation. Effects of anesthetics on these transport mechanisms could play critical roles in anesthesia by inducing deprivation-sensing pathways including GCN. Similar effects in nonneuronal cells may be responsible for anesthetic side effects.

Acknowledgments

Jody L. Henry and Thomas Reiner provided expert technical assistance for this work. We thank Drs. P. G. Morgan, Anita Hopper, Jim Jefferson, and Scot Kimball and Nikki Keasey for critical comments regarding this manuscript; Drs. A. G. Hinnebusch, T. E. Dever, and R. C. Wek for plasmids; Dr. R. C. Wek for antibodies; and Drs. Jim Jefferson and Scot Kimball and Sharon Rannels for assistance with polysome profile preparation and use of their ISCO Density Gradient Fractionator. This work was supported in part by Grant GM57822 to R.L.K. from the National Institutes of Health.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0127) on June 1, 2005.

References

- Abastado, J. P., Miller, P. F., Jackson, B. M., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1991). Suppression of ribosomal reinitiation at upstream open reading frames in amino acid-starved cells forms the basis for GCN4 translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 486-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alani, E., Cao, L., and Kleckner, N. (1987). A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics 116, 541-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arava, Y., Wang, Y., Storey, J. D., Liu, C. L., Brown, P. O., and Herschlag, D. (2003). Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3889-3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe, M. P., Slaven, J. W., De Long, S. K., Ibrahimo, S., and Sachs, A. B. (2001). A novel eIF2B-dependent mechanism of translational control in yeast as a response to fusel alcohols. EMBO J. 20, 6464-6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batai, I., Kerenyi, M., and Tekeres, M. (1999). The impact of drugs used in anaesthesia on bacteria. Eur. J. Anaesth. 16, 425-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigan, A. M., Bushman, J. L., Boal, T. R., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1993). A protein complex of translational regulators of GCN4 mRNA is the guanine nucleotide-exchange factor for translation initiation factor 2 in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 5350-5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloche, O., de la Cruz, J., Kressler, D., Doere, M., and Linder, P. (2004). A membrane transport defect leads to a rapid attenuation of translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 13, 357-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever, T. E., Chen, J. J., Barber, G. N., Cigan, A. M., Feng, L., Donahue, T. F., London, I. M., Katze, M. G., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1993). Mammalian eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinases functionally substitute for GCN2 protein kinase in the GCN4 translational control mechanism of yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 4616-4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever, T. E., Feng, L., Wek, R. C., Cigan, A. M., Donahue, T. F., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1992). Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2α by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene-specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell 68, 585-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Maghrabi, E. A., and Eckenhoff, R. G. (1993). Inhibition of dopamine transport in rat brain synaptosomes by volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology 78, 750-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg, D., Klein, C., Martinetto, H., Struhl, K., and Karin, M. (1994). The UV response involving the Ras signaling pathway and AP-1 transcription factors is conserved between yeast and mammals. Cell 77, 381-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaim, K. E., Jefferson, L. S., McGwire, J. B., and Rannels, D. E. (1983). Effect of halothane on synthesis and secretion of liver proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 24, 277-281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game, J. C., and Cox, B. S. (1972). Epistatic interactions between four rad loci in yeast. Mutat. Res. 16, 353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game, J. C., and Cox, B. S. (1973). Synergistic interactions between rad mutations in yeast. Mutat. Res. 20, 35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelperin, D., Horton, L., DeChant, A., Hensold, J., and Lemmon, S. K. (2002). Loss of Ypk1 function causes rapamycin sensitivity, inhibition of translation initiation and synthetic lethality in 14-3-3-deficient yeast. Genetics 161, 1453-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever, G. et al. (2002). Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418, 387-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, A., Dever, T. E., Pascual-Ahuir, A., and Serrano, R. (2001). The protein kinase Gcn2p mediates sodium toxicity in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30753-30760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gstaiger, M., Luke, B., Hess, D., Oakeley, E. J., Wirbelauer, C., Blondel, M., Vigneron, M., Peter, M., and Krek, W. (2003). Control of nutrient-sensitive transcription programs by the unconventional prefoldin URI. Science 302, 1208-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente, L. (1983). Yeast promoters and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 101, 181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldener, U., Heck, S., Fielder, T., Beinhauer, J., and Hegemann, J. H. (1996). A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 2519-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, J. A., and Rannels, D. E. (1981). Effects of halothane on protein synthesis and degradation in rabbit pulmonary macrophages. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 124, 50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannig, E. M., Williams, N. P., Wek, R. C., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1990). The translational activator GCN3 functions downstream from GCN1 and GCN2 in the regulatory pathway that couples GCN4 expression to amino acid availability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 126, 549-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, J. W. (1991). Translational control in mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60, 717-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch, A. G. (1984). Evidence for translational regulation of the activator of general amino acid control in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 6442-6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch, A. G. (1985). A hierarchy of trans-acting factors modulates translation of an activator of amino acid biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 2349-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch, A. G., and Natarajan, K. (2002). Gcn4p, a master regulator of gene expression, is controlled at multiple levels by diverse signals of starvation and stress. Eukaryot. Cell 1, 22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, L. S., and Kimball, S. R. (2003). Amino acids as regulators of gene expression at the level of mRNA translation. J. Nutr. 133, 2046S-2051S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, M. H., Larossa, R. A., Lee, J. M., Rafalski, A., Derose, E., Gonye, G., and Xue, Z. X. (2000). Global expression profiling of yeast treated with an inhibitor of amino acid biosynthesis, sulfometuron methyl. Physiol. Genomics 3, 83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil, R. L., Wolfe, D., Reiner, T., Peterson, C. J., and Riley, J. L. (1996). Molecular genetic analysis of volatile-anesthetic action. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3446-3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin, D. D. (2000). Mechanisms of action. In: Anesthesia, Vol. 1, 5th Ed., ed. R. D. Miller, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 48-73. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M., and Langmoen, I. A. (1998). The effect of volatile anaesthetics on synaptic release and uptake of glutamate. Toxicol. Lett. 100–101, 59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-H., and Keil, R. L. (1991). Mutations affecting RNA polymerase I-stimulated exchange and rDNA recombination in yeast. Genetics 127, 31-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorberg, A., and Hall, M. N. (2004). TOR: the first 10 years. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 279, 1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. C., Adams, R. J., and Aronstam, R. S. (1990). The influence of isoflurane on the synaptic activity of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neurochem. Res. 15, 969-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marton, M. J., Crouch, D., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1993). GCN1, a translational activator of GCN4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 by protein kinase GCN2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 3541-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, P. P., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1986). Multiple upstream AUG codons mediate translational control of GCN4. Cell 45, 201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, K., Meyer, M. R., Jackson, B. M., Slade, D., Roberts, C., Hinnebusch, A. G., and Marton, M. J. (2001). Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 4347-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton, C. E. (1901). Studies of Narcosis, Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer.

- Palmer, L. K., Wolfe, D., Keeley, J. L., and Keil, R. L. (2002). Volatile anesthetics affect nutrient availability in yeast. Genetics 161, 563-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, G. L. (1977). A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal. Biochem. 83, 346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannels, D. E., Christopherson, R., and Watkins, C. A. (1983). Reversible inhibition of protein synthesis in lung by halothane. Biochem. J. 210, 379-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannels, D. E., Roake, G. M., and Watkins, C. A. (1982). Additive effects of pentobarbital and halothane to inhibit synthesis of lung proteins. Anesthesiology 57, 87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., Novick, P., Thomas, J. H., Botstein, D., and Fink, G. R. (1987). A Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic plasmid bank based on a centromere-containing shuttle vector. Gene 60, 237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., Winston, F., and Hieter, P. (1990). Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Shimada, H., Tomita, Y., Inooka, G., and Maruyama, Y. (1995). Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid cotransporter inhibited by the volatile anesthetic, halothane, in megakaryocytes. Jpn. J. Physiol. 45, 165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. S., and Hieter, P. (1989). A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura, M., Kitayama, S., Morita, K., Irifune, M., Takarada, T., Kawahara, M., and Dohi, T. (2001). Effects of volatile and intravenous anesthetics on the uptake of GABA, glutamate and dopamine by their transporters heterologously expressed in COS cells and in rat brain synaptosomes. Toxicol. Lett. 123, 69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzamarias, D., Roussou, I., and Thireos, G. (1989). Coupling of GCN4 mRNA translational activation with decreased rates of polypeptide chain initiation. Cell 57, 947-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez de Aldana, C. R., Dever, T. E., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1993). Mutations in the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF-2 alpha) that overcome the inhibitory effect of eIF-2 alpha phosphorylation on translation initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 7215-7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez de Aldana, C. R., Marton, M. J., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1995). GCN20, a novel ATP binding cassette protein, and GCN1 reside in a complex that mediates activation of the eIF-2 alpha kinase GCN2 in amino acid-starved cells. EMBO J. 14, 3184-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartell, S. A., Christopherson, R., Watkins, C. A., and Rannels, D. E. (1981). Inhibition of synthesis of lung proteins by halothane. Mol. Pharmacol. 19, 520-524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek, R. C., Cannon, J. F., Dever, T. E., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1992). Truncated protein phosphatase GLC7 restores translational activation of GCN4 expression in yeast mutants defective for the eIF-2 alpha kinase GCN2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 5700-5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek, R. C., Jackson, B. M., and Hinnebusch, A. G. (1989). Juxtaposition of domains homologous to protein kinases and histidyl-tRNA synthetases in GCN2 protein suggests a mechanism for coupling GCN4 expression to amino acid availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 4579-4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek, S. A., Zhu, S., and Wek, R. C. (1995). The histidyl-tRNA synthetase-related sequence in the eIF-2α protein kinase GCN2 interacts with tRNA and is required for activation in response to starvation for different amino acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4497-4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N. P., Hinnebusch, A. G., and Donahue, T. F. (1989). Mutations in the structural genes for eukaryotic initiation factors 2 alpha and 2 beta of Saccharomyces cerevisiae disrupt translational control of GCN4 mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 7515-7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler, E. A. et al. (1999). Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285, 901-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, D., Hester, P., and Keil, R. L. (1998). Volatile anesthetic additivity and specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for yeast as a model system to study mechanisms of anesthetic action. Anesthesiology 89, 174-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, D., Reiner, T., Keeley, J. L., Pizzini, M., and Keil, R. L. (1999). Ubiquitin metabolism affects cellular response to volatile anesthetics in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8254-8262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfner, M., Yep, D., Messenguy, F., and Fink, G. R. (1975). Integration of amino acid biosynthesis into the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 96, 273-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R., Wek, S. A., and Wek, R. C. (2000). Glucose limitation induces GCN4 translation by activation of Gcn2 protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2706-2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff, M. (1997). Brain metabolism of branched-chain amino acids. Glia 21, 92-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff, M., Daikhin, Y., Lin, Z. P., Nissim, I., Stern, J., and Pleasure, D. (1994). Interrelationships of leucine and glutamate metabolism in cultured astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 62, 1192-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. et al. (2002). The GCN2 eIF2α kinase is required for adaptation to amino acid deprivation in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6681-6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]