Abstract

Introduction

This study was to investigate whether the expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9 (ADAM9) is correlated with the expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), to evaluate the significance of HDGF and ADAM9 as novel molecular staging biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers and predictive biomarkers for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in surgically resected stage I NSCLC, to provide essential consistence proof to the possible novel pathway of HDGF–ADAM9 pathway.

Methods

Sixty-three cases of resected stage I NSCLC with mediastinal N2 lymph node dissection were immunohistochemically analyzed for HDGF and ADAM9 protein expression. Multivariate analysis and survival analysis were conducted.

Results

HDGF and ADAM9 were observed highly expressed in NSCLC compared with normal control lung tissues (P < 0.05). HDGF high expression cases showed significantly lower survival rate (55.6 vs. 84.7 %, P = 0.009). HDGF high expression was an independent factor of shortened survival time in resected stage I NSCLC (P = 0.015). ADAM9 high expression cases showed significantly lower survival rate (56.9 vs. 88.7 %, P = 0.015). ADAM9 high expression was an independent factor of shortened survival time in resected stage I NSCLC (P = 0.021). Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that ADAM9 expression was correlated positively and significantly with HDGF expression in 63 cases of stage I NSCLC (r = 0.547, P = 0.000).

Conclusion

These results clearly demonstrate that ADAM9 high expression is correlated positively and significantly with HDGF high expression, which provides essential evidence for the novel HDGF–ADAM9 pathway, through which HDGF promotes invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells; HDGF and ADAM9 are novel molecular staging biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers, which might become useful predictive biomarkers for the selection of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

Keywords: HDGF, ADAM9, Lung cancer, Prognostic biomarker, Molecular staging biomarker

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the USA, China, and many other countries in the world. Generally, the overall 5-year survival rate is still as low as 10–17 % (Siegel et al. 2013; Mountain 1997). The 5-year survival rate for resected stage I NSCLC ranges between 60–70 %, and 30–40 % of early stage patients die within 5 years of surgery because of relapse and metastasis (Mountain 1997; Nesbitt et al. 1995; Molina et al. 2008), suggesting that certain cases of stage I NSCLC need further postoperative treatment to improve the prognosis. Novel prognostic biomarkers and molecular staging biomarkers are urgently needed to set up a novel molecular staging system, to help distinguish “bad” stage I NSCLC with worse prognosis from “good” ones with better prognosis, to help make decisions about “bad” stage I (IA) NSCLC to receive appropriate postoperative treatment such as adjuvant chemotherapy, which stage I (IA) NSCLC clinically will usually not receive postoperative chemotherapy; meanwhile, to help avoid unnecessary poisonous damage from chemotherapy for those “good” stage I (IB) NSCLC, which would be predicted with better prognosis according to the molecular staging systems based on novel molecular staging biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers, and predictive biomarkers for postoperative chemotherapy.

We recently found that hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) is one key gene involved in invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells (Zhang et al. 2006, 2011; Zhang 2006). HDGF was detected highly expressed in NSCLC cells and human NSCLC tissues; when using siRNA silencing HDGF in NSCLC cells, anchorage-independent growth and migration through BD Matrigel (in vitro) as well as the formation and growth of subdermal xenograft tumors in nude mice (in vivo) were inhibited significantly. Affymetrix U133A gene chip microarray revealed that, with HDGF silenced by specific targeting-HDGF siRNA, a series of genes including a disintegrin and metalloproeinase-9 (ADAM9) were downregulated, implicating the possible molecular mechanism for the novel invasion–metastasis-related key gene of HDGF.

We preliminarily tested the correlation of ADAM9 with HDGF expression before (abstract in Chinese; Zhang et al. 2011); here, we report in detail on the correlation between ADAM9 and HDGF expression at protein levels, HDGF and ADAM9 as molecular staging biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers and predictive biomarkers for postoperative chemotherapy in surgically resected stage I NSCLC [Abstract was published in the 15th World Conference on Lung Cancer, Sydney, 2013 (Zhang et al. 2013)].

Materials and methods

Patients and tissues

As previously reported (Zhang et al. 2011, 2013), formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were obtained from 64 cases of completely resected NSCLC with mediastinal N2 lymph node dissection who underwent surgery at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, The First Hospital of China Medical University (Shenyang, China) between April 2000 and May 2006. All patients underwent standard lobectomy and mediastinal N2 lymph node dissection. Preoperative examinations of liver ultrasound, brain computed tomography (CT) and bone scintigraphy were performed to exclude the presence of distant metastasis. The following criteria were used to exclude patients: The patients received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, died within 3 months of surgery or succumbed to a cause other than NSCLC.

Out of 64 cases, 63 cases were available for HDGF detection. This total of 63 patients in this group consisted of 35 males and 28 females who ranged in age between 33 and 76 years (median age, 60 years). Histological types were determined according to the WHO 2000 classification: 15 cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 48 cases of adenocarcinoma. Postoperative pathological stage was classified according to the UICC and AJCC TNM staging system (Mountain 1997): T1N0M0 stage IA, 23 cases (36.5 %); T2N0M0 stage IB, 40 cases (63.5 %). Normal control lung tissue was collected from 5 cm away from the lung tumor site in 12 cases of completely resected stage IA lung cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis for 63 cases of resected stage I NSCLC

| Variable | n | Proportion (%) | 5-year survival (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | 63 | 100 | 71.5 | |

| HDGF expression | 0.009* | |||

| Low expression | 34 | 54.0 | 84.7 | |

| High expression | 29 | 46.0 | 55.6 | |

| ADAM9 expression | 0.015* | |||

| Low expression | 29 | 46.0 | 88.7 | |

| High expression | 34 | 54.0 | 56.9 | |

| Gender | 0.977 | |||

| Male | 35 | 55.6 | 74.3 | |

| Female | 28 | 44.4 | 69.0 | |

| Age(year) | 0.692 | |||

| <60 | 30 | 47.6 | 68.1 | |

| ≥60 | 33 | 52.4 | 74.8 | |

| Histological type | 0.259 | |||

| Squamous | 15 | 23.8 | 86.7 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 48 | 76.2 | 67.0 | |

| Pathologic stage | 0.572 | |||

| IA | 23 | 36.5 | 70.4 | |

| IB | 40 | 63.5 | 71.5 |

NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, HDGF: hepatoma-derived growth factor, ADAM9 a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9

* P < 0.05

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the First Hospital of China Medical University, and informed consent was obtained.

Immunohistochemistry staining

Briefly, the primary rabbit polyclonal HDGF antibody was a gift from Professor Allen Everett (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA), diluted with PBS (1:10,000). The specificity and sensitivity of the antibody used had been well tested (Zhang et al. 2006, 2011; Everett et al. 2000, 2004). After incubation overnight at 4 °C, biotin-labeled goat-anti rabbit IgG (Maixin Bio, Fuzhou, China) was used as a secondary antibody incubated for 15 min at room temperature, followed by Streptavidin–Peroxidase (S–P; Maixin Bio, Fuzhou, China) incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Immunohistochemistry staining was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) system for 1–3 min. Afterward, the slides were briefly counterstained with hematoxylin. HDGF-positive NSCLC slides were used as the positive control, and the HDGF-positive slides in which the primary antibody was omitted during staining were used as the negative control.

The positive cells were stained from yellow to brown in the nuclei. For each section, five fields of vision were selected and a total 1,000 tumor cells were counted and evaluated (200 tumor cells in each field of vision). The staining (A) was scored as follows: 0, negative; 1, lower than the staining intensity of nuclei of blood vessel endothelial cells; 2, equal to the staining intensity of nuclei of blood vessel endothelial cells that served as an intern control; and 3, higher than the staining intensity of nuclei of blood vessel endothelial cells. The percentage of positive tumor cells (B) was calculated. The immunostaining index was calculated as the multiplication of A and B. All of the cases were divided by average staining index into two groups, HDGF high expression (HDGF high) group and HDGF low expression (HDGF low) group. The immunostaining was evaluated independently by two pathologists who were blinded to the patients’ score.

For ADAM9, the primary goat polyclonal ADAM9 antibody (AF949) was bought from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and diluted with PBS (1:50). The specificity and sensitivity of the antibody used had been well tested (Zhang et al. 2011, 2013; Grutzmann et al. 2004; Fritzsche et al. 2008a, b). Biotin-labeled rabbit-anti goat IgG (Maixin Bio, Fuzhou, China) was used as a secondary antibody, followed by Streptavidin–Peroxidase (S–P; Maixin Bio, Fuzhou, China) and DAB system. ADAM9-positive NSCLC slides were used as the positive control, and the ADAM9-positive slides in which the primary antibody was omitted during staining were used as the negative control.

The positive cells were stained from yellow to brown in the cytoplasm and cell membrane. For each section, five fields of vision were selected and a total of 1,000 tumor cells were counted and evaluated (200 tumor cells in each field of vision). The staining index was evaluated semiquantitatively as negative, weak, moderate or strong by the multiplication of the staining intensity (A) and the percentage of positive tumor cells (B). The staining intensity was scored as follows: 1, light yellow; 2, yellow; and 3, brown. The percentage of positive tumor cells was scored as follows: 0, positive tumor cells <5 %; 1, 5–10 %; 2, 11–50 %; 3, 51–75 %; and 4, >75 %. The total score (immunostaining index) was the multiplication of A and B and was classified as follows: A score of 0 was considered as negative (−); 1–4 was considered weak (+); 5–8 as moderate (++); and 9–12 as strong (+++). All of the cases were divided by average immunostaining index into two groups, ADAM9 high expression (ADAM9 high) group and ADAM9 low expression (ADAM9 low) group. The immunostaining was evaluated independently by two pathologists who were blinded to the patients’ score.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 17.0. A chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess the correlation between HDGF, ADAM9 expression and clinicopathological characteristics. For the survival analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method was used for a univariate analysis, and the differences in survival curves were assessed with the Log-rank test. The Cox regression model was used for multivariate survival analysis. P < 0.05 (two-tailed test) was considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

Results

Highly expressed HDGF in NSCLC tissue predicted a worse prognosis

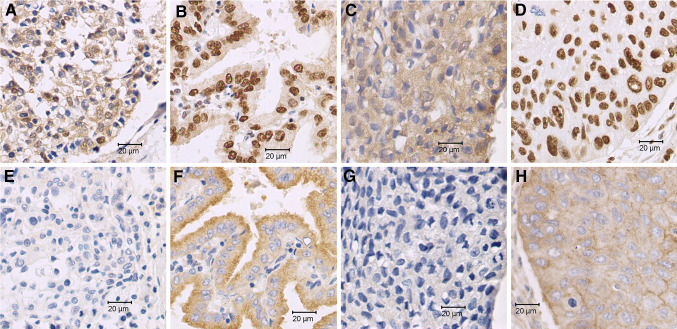

HDGF expression was mainly identified in the nuclei (Fig. 1a–d). Normal control bronchial epithelial cells and alveolar epithelial cells were stained as negative, weak staining or even moderate staining, when compared with intern control of blood vessel endothelial cells. All twelve normal control tissues belonged to HDGF low expression group, when compared with the average immunostaining index of tumor cells. In 63 cases of completely resected stage I NSCLC, 46.0 % (29/63) demonstrated highly expressed HDGF protein, significantly higher when compared with normal control lung tissue (P = 0.003). No difference between the HDGF high rates between the stage IA and IB groups was identified (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9 (ADAM9) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissues (Immunohistochemistry SP method, ×400). a Low expression of HDGF (nuclei staining) in adenocarcinoma of the lung; b high expression of HDGF (nuclei staining) in adenocarcinoma of the lung; c low expression of HDGF (nuclei staining) in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung; and d high expression of HDGF (nuclei staining) in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. e low expression of ADAM9 (cytoplasm staining) in adenocarcinoma of the lung; f High expression of ADAM9 (cytoplasm staining) in adenocarcinoma of the lung; g Low expression of ADAM9 (cytoplasm staining) in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung; and h High expression of ADAM9 (cytoplasm staining) in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (e, f, g, h are counterpart slides (from the same cases) of a, b, c, and d, respectively)

The overall 5-year survival rate for the group of 63 completely resected stage I NSCLC cases with local hilar (N1) and mediastinal (N2) lymph node dissection was 71.5 % (Fig. 2a). There was no statistic difference between the overall 5-year survival rates of stage IA and stage IB NSCLC in this group (70.4 % vs. 71.5 %, P = 0.572).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival; correlation between the expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9 (ADAM9) and hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF). a. Showed the overall survival of all 63 cases of stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the 5-year survival rate is 71.5 %. b. Showed the difference between HDGF high expression and low expression groups in 63 stage I NSCLC (P = 0.009). c Showed the difference between ADAM9 high expression and low expression groups in 63 stage I NSCLC (P = 0.015). d Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that ADAM9 expression correlated significantly with HDGF expression in 63 stage I NSCLC (r = 0.547, P = 0.000)

When stratified by HDGF expression, the 5-year survival rate in the HDGF low group (34 cases) was as high as 84.7 %; however, the 5-year survival rate sharply decreased to 55.6 % in the HDGF high group (29 cases). The difference between these two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.009; Table 1, Fig. 2b).

When further stratified in 23 stage IA cases, the 5-year survival rate for HDGF low expression group (9 cases) was 100 %, it sharply decreased to 42.9 % for HDGF high expression group (14 cases), the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.017). In the 40 stage IB cases, the 5-year survival rate for HDGF low expression group (25 cases) was 79.1 %, but it decreased sharply to 59.3 % for HDGF high expression group (15 cases); however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.112).

The Cox regression model was used for multivariate survival analysis: patient gender, age, smoking status, histological type, pathological stage (IA and IB) and HDGF high/low expression were entered into the Cox proportional hazard regression model. The results demonstrated that HDGF high/low expression was an independent predictor of prognosis for this group of completely resected stage I NSCLC (HR 5.958; 95 % CI 1.274–9.179, P = 0.015).

Highly expressed ADAM9 in NSCLC tissue predicted a worse prognosis

ADAM9 expression was mainly identified in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1e–h). In normal control lung tissue, ADAM9 staining was mainly observed to be negatively or weakly expressed and scores belonged to the ADAM9 low group. The ADAM9 high rate was 0 % (0/12) in normal control lung tissues. In 63 cases of completely resected stage I NSCLC, 54.0 % (34/63) demonstrated highly expressed ADAM9 protein, significantly higher when compared with normal control lung tissue (P = 0.001). No difference between the ADAM9 high rates between the stage IA and IB groups was identified (P > 0.05).

As described above, the overall 5-year survival rate for the group of 63 completely resected stage I NSCLC cases with local hilar (N1) and mediastinal (N2) lymph node dissection was 71.5 % (Fig. 2a). There was no statistic difference between the overall 5-year survival rates of stage IA and stage IB NSCLC in this group (70.4 vs. 71.5 %, P = 0.572).

When stratified by ADAM9 expression, the 5-year survival rate in the ADAM9 low group (29 cases) was as high as 88.7 %; however, the 5-year survival rate sharply decreased to 56.9 % in the ADAM9 high group (34 cases). The difference between these two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.015; Table 1, Fig. 2c).

When further stratified: in 23 stage IA cases, the 5-year survival rate for ADAM9 low expression group (7 cases) was 100 %, it sharply decreased to 55.0 % for ADAM9 high expression group (16 cases), however, the difference was not statistically significant when two-tailed test applied (P = 0.062). In the 40 stage IB cases, the 5-year survival rate for ADAM9 low expression group (22 cases) was 84.8 %, but it decreased sharply to 55.6 % for ADAM9 high expression group (18 cases), the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.030).

The Cox regression model was used for multivariate survival analysis: patient gender, age, smoking status, histological type, pathological stage (IA and IB) and ADAM9 high/low expression were entered into the Cox proportional hazard regression model. The results demonstrated that ADAM9 high/low expression was an independent predictor of prognosis for this group of completely resected stage I NSCLC (HR 3.306; 95 % CI 1.195–9.147, P = 0.021).

HDGF high expression and ADAM9 high expression were positively and significantly correlated in NSCLC

Among 29 cases of HDGF high group, 79.3 % (23 cases) belonged to ADAM9 high group; among 34 cases of HDGF low group, 67.6 % (23 cases) belonged to ADAM9 low group; the consistency rate of expression of HDGF and ADAM9 was 73.0 % (46 cases). Among 34 cases of ADAM9 high group, 67.6 % (23 cases) belonged to HDGF high group; among 29 cases of ADAM9 low group, 79.3 % (23 cases) belonged to HDGF low group; the consistency rate of expression of ADAM9 and HDGF was 73.0 % (46 cases). Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that ADAM9 expression was correlated positively and significantly with HDGF expression in 63 cases of stage I NSCLC (r = 0.547, P = 0.000; Fig. 2d).

Discussion

HDGF was recently found highly expressed in solid malignant tumors, such as esophageal cancer (Yamamoto et al. 2007), gastric cancer (Yamamoto et al. 2006), hepatoma (Zhou et al. 2010), pancreatic cancer (Uyama et al. 2006), correlated with a worse prognosis (Yamamoto et al. 2007, 2006; Zhou et al. 2010; Uyama et al. 2006). High expression of HDGF in NSCLC was also found (Zhang et al. 2011; Ren et al. 2004; Iwasaki et al. 2005). We detected HDGF in 158 Chinese NSCLC (Zhang et al. 2011), confirmed that HDGF was highly expressed in surgically resected NSCLC and correlated with shortened survival time; these results are similar with that found in American and Japanese NSCLC (Ren et al. 2004; Iwasaki et al. 2005).

In this paper, we further discussed the important role of HDGF as a molecular staging biomarker, which may classify stage I NSCLC into two molecular stages: subgroup of HDGF high stage I and subgroup of HDGF low stage I NSCLC.

Even though there was no statistic difference between the overall 5-year survival rates of stage IA and stage IB NSCLC in this group (P = 0.572); however, when stratified by HDGF expression levels, the 5-year survival rate in subgroup of HDGF low stage I NSCLC was as high as 84.7 %, the 5-year survival rate sharply decreased to 55.6 % in subgroup of HDGF high stage I NSCLC; the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.009). This suggested that HDGF is not only a novel useful prognostic biomarker but also a novel useful molecular staging biomarker, and this molecular staging system may become an important complementary part to TNM stage system, especially for stage I NSCLC.

The 5-year survival rate 55.6 % in subgroup of HDGF high stage I NSCLC is almost similar to the 5-year survival rate in stage II NSCLC (Mountain 1997; Nesbitt et al. 1995; Molina et al. 2008); obviously, this subgroup of HDGF high stage I NSCLC should receive further postoperative treatment such as chemotherapy to improve the prognosis. So HDGF might also be a novel useful predictive biomarker for the selection of postoperative chemotherapy for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

When further stratified in 23 stage IA cases, the 5-year survival rate for subgroup of HDGF low stage IA NSCLC was 100 %, it sharply decreased to 42.9 % for the subgroup of HDGF high stage IA NSCLC; the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.017). This subgroup of HDGF high stage IA NSCLC, with a significantly lower survival rate, should be advised to receive further postoperative treatment of chemotherapy to improve prognosis, even though, usually stage IA NSCLC needs no further postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy after standard surgery. In the 40 stage IB cases, the 5-year survival rate for subgroup of HDGF low stage IB NSCLC was 79.1 % and it decreased sharply to 59.3 % for subgroup of HDGF high stage IB NSCLC; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.112). This suggested further testing is needed. The trend from the limited number cases suggested that certain stage IB NSCLC, such as subgroup of HDGF high stage IB with a lower survival rate, should receive postoperative chemotherapy; however, certain stage IB NSCLC, such as subgroup of HDGF low stage IB NSCLC with a relatively high survival rate, may need no further postoperative chemotherapy.

Multivariate survival analysis by Cox regression model revealed that HDGF high/low expression levels, not patient gender, age, smoking status, histological type, or pathological stage (IA and IB), was an independent predictor of prognosis for this group of completely resected stage I NSCLC (P = 0.015), which confirmed the importance and reliability of HDGF as a novel useful prognostic biomarker for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

So based on above findings, HDGF is a very useful prognostic biomarker for stage I NSCLC, a very useful molecular staging biomarker; importantly, HDGF might be a very useful predictive biomarker for the selection of postoperative chemotherapy for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

To elucidate HDGF’s molecular biological mechanism, we used siRNA silencing HDGF in NSCLC cells (Zhang et al. 2006; Zhang 2006), a series of genes including AXL (Wimmel et al. 2001), GLO1 (Liu and Zhang 2013) and ADAM9 (Zhang et al. 2011, 2013) were induced to be downregulated, anchorage-independent growth and migration through BD Matrigel (in vitro) as well as the formation and growth of subdermal xenograft tumor in nude mice (in vivo) were inhibited significantly (Zhang et al. 2006; Zhang 2006), suggesting that ADAM9 pathway may be one of the signal transduction pathways through which HDGF promote invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells.

Highly expressed ADAM9 was found in breast cancer (O’Shea et al. 2003), liver cell carcinoma (Tannapfel et al. 2003), gastric cancer (Carl-McGrath et al. 2005), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Grutzmann et al. 2004), prostate cancer (Fritzsche et al. 2008a), renal cell carcinoma (Fritzsche et al. 2008b) and cervical squamous carcinoma (Zubel et al. 2009), correlating with cancer progression, metastasis and predicting a shortened survival time in patients (Grutzmann et al. 2004; Fritzsche et al. 2008a, b; O’Shea et al. 2003; Tannapfel et al. 2003; Carl-McGrath et al. 2005; Zubel et al. 2009). Just recently, we reported for the first time that ADAM9 high expression was detected in resected NSCLC tissues (Zhang et al. 2011, 2013) and confirmed that ADAM9 high expression was correlated with shortened survival time in completely resected stage I NSCLC.

In this paper, we further discussed the important role of ADAM9 as molecular staging biomarker, which may classify stage I NSCLC into two molecular stages: subgroup of ADAM9 high stage I and subgroup of ADAM9 low stage I NSCLC.

Even though there was no statistic difference between the overall 5-year survival rates of stage IA and stage IB NSCLC in this group; however, when stratified by ADAM9 expression levels, the 5-year survival rate in ADAM9 low stage I subgroup was 88.7 %, the 5-year survival rate sharply decreased to 56.9 % in ADAM9 high stage I subgroup; the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.015). This suggested that ADAM9 is not only a novel useful prognostic biomarker but also a novel useful molecular staging biomarker, and this molecular staging system may become an important complementary part to TNM stage system, especially for stage I NSCLC.

The 5-year survival rate 56.9 % in ADAM9 high stage I subgroup, generally, is almost similar to the 5-year survival rate in stage II NSCLC (Mountain 1997; Nesbitt et al. 1995; Molina et al. 2008); obviously, this subgroup of ADAM9 high stage I NSCLC should receive further postoperative treatment such as chemotherapy to improve the prognosis. So ADAM9 might also be a novel useful predictive biomarker for the selection of postoperative chemotherapy for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

When further stratified in 23 stage IA cases, the 5-year survival rate for ADAM9 low stage IA subgroup was 100 %, it sharply decreased to 55.0 % for ADAM9 high stage IA subgroup; however, the difference was not statistically significant when two-tailed test applied (P = 0.062). This subgroup of ADAM9-high stage IA NSCLC, with a relatively lower survival rate, obviously, should also be considered to receive further postoperative treatment of chemotherapy to improve the prognosis, even though, usually stage IA NSCLC needs no further postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy after standard surgery. In the 40 stage IB cases, the 5-year survival rate for ADAM9-low stage IB sub-group was 84.8 %, but it decreased sharply to 55.6 % for ADAM9-high stage IB sub-group, the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.030). Obviously, this sub-group of ADAM9 high stage IB with a significantly lower survival rate should receive postoperative chemotherapy; however, certain stage IB NSCLC, such as subgroup of ADAM9 low stage IB NSCLC with a relatively high survival rate, may have no need to receive further postoperative chemotherapy.

Cox regression model revealed that ADAM9 high/low expression levels, not patient gender, age, smoking status, histological type or pathological stage (IA and IB), was an independent predictor of prognosis for this group of completely resected stage I NSCLC (P = 0.021), which confirmed the importance and reliability of ADAM9 as a novel useful prognostic biomarker for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

So based on above findings, ADAM9 is a very useful prognostic biomarker for stage I NSCLC, a very useful molecular staging biomarker; importantly, ADAM9 might be a very useful predictive biomarker for the selection of postoperative chemotherapy for surgically resected stage I NSCLC.

To test the correlation between HDGF and ADAM9 expression, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted, which revealed that ADAM9 expression was correlated positively and significantly with HDGF expression in 63 cases of stage I NSCLC (r = 0.547, P = 0.000). These findings provide essential evidence for the novel HDGF–ADAM9 pathway, through which HDGF promotes invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells.

The molecular stage systems based on novel biomarkers of HDGF and ADAM9 could predict prognosis, importantly, could help make decision for the selection of postoperative chemotherapy. As we know, postoperative chemotherapy could benefit NSCLC (Besse and Chevalier 2008; Douillard and Gauducheau 2010), but in certain cases, it becomes harmful (Besse and Chevalier 2008; Douillard and Gauducheau 2010). Zhu et al. (2010), Xie and Minna (2010) recently reported the use of prognostic signatures to divide NSCLC patients into two groups; a high-risk and a low-risk group. Patients who were predicted a “worse” prognosis benefited significantly from adjuvant chemotherapy; however, the patients who were predicted with “better” prognosis did not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, suggesting that subgrouping by valuable prognostic biomarkers is important in prognosis judgment, especially in helping to make the decision of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (Zhu et al. 2010; Xie and Minna 2010).

HDGF and ADAM9 could distinguish “good” stage I NSCLC from “bad” ones. Prospective studies based on HDGF and ADAM9 molecular staging systems are needed to conduct to distinguish “good” stage IA and stage IB NSCLC to avoid unnecessary adjuvant chemotherapy, to distinguish “bad” stage IA and stage IB NSCLC to conduct postoperative chemotherapy to improve the prognosis of stage I NSCLC. These molecular staging systems, which could not only predict prognosis, but also predict the necessity of postoperative chemotherapy, will become important complementary parts to the usual TNM stage system, especially for stage I NSCLC.

In conclusion, we confirmed for the first time that ADAM9 and HDGF are positively and significantly correlated, which provides essential evidence for the novel HDGF–ADAM pathway, through which HDGF promotes invasion and metastasis of NSCLC cells. HDGF and ADAM9 are novel and useful prognostic biomarkers, molecular staging biomarkers and predictive biomarkers for selection of postoperative personalized adjuvant chemotherapy for completely resected stage I NSCLC patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank C. Guan for technical assistance of immunohistochemistry staining, Dr. Y. Han and Dr. A. He for immunostaining evaluation and discussion. The authors appreciate Mr. Philip Whatley for copyediting the manuscript. This study was supported in part by IASLC/CRFA Prevention Fellowship, grants from The Education Department of Liaoning Province (No. 20060991) and from the Nature Science Foundation of Liaoning Province, China (No. 20102285), and Fund for Scientific Research of The First Hospital of China Medical University (No. FSFH1210).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Besse B, Chevalier TL (2008) Adjuvant chemotherapy for non–small-cell lung cancer: a fading effect? JCO 26:5014–5017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl-McGrath S, Lendeckel U, Ebert M, Roessner A, Röcken C (2005) The disintegrin-metalloproteinases ADAM9, ADAM12, and ADAM15 are upregulated in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 26:17–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douillard JY, Gauducheau CR (2010) Adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: it does not always fade with time. JCO 28(1):3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett AD, Lobe DR, Matsumura ME, Nakamura H, McNamara CA (2000) Hepatoma-derived growth factor stimulates smooth muscle cell growth and is expressed in vascular development. J Clin Invest 105:567–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett AD, Narron JV, Stoops T, Nakamura H, Tucker A (2004) Hepatoma-derived growth factor is a pulmonary endothelial cell-expressed angiogenic factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286:L1194–L1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche FR, Jung M, Tölle A et al (2008a) ADAM9 Expression is a significant and independent prognostic marker of PSA relapse in prostate cancer. Eur Urol 54:1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche FR, Wassermann K, Jung M et al (2008b) ADAM9 is highly expression in renal cell cancer and is associated with tumour progression. BMC Cancer 8:179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzmann R, Luttges J, Sipos B et al (2004) ADAM9 expression in pancreatic cancer is associated with tumour type and is a prognostic factor in ductal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 90:1053–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T, Nakaqawa K, Nakamura H, Takada Y, Matsui K, Kawahara K (2005) Hepatoma-derived growth factor as a prognostic marker in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 13:1075–1080 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Zhang J (2013) Abnormal expression of GLO1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Yike Daxue Xuebao 42:77–78 (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA (2008) Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 83:584–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain CF (1997) Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 111:1710–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt JC, Putnam JB Jr, Walsh GL, Roth JA, Mountain CF (1995) Survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 60:466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea C, Mckie N, Buggy Y et al (2003) Expression of ADAM9m RNA and protein in human breast cancer. Int J Cancer 105:754–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Tang X, Lee JJ et al (2004) Expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor is a strong prognostic predictor for patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO 22:3230–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63:11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannapfel A, Anhalt K, Hausermann P et al (2003) Identification of novel proteins associated with hepatocellular carcinomas using protein microarrays. J Pathol 201:238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyama H, Tomita Y, Nakamura H et al (2006) Hepatoma-derived growth factor is a novel prognostic factor for patients with pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 12:6043–6048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmel A, Glitz D, Kraus A, Roeder J, Schuermann M (2001) Axl receptor tyrosine kinase expression in human lung cancer cell lines correlates with cellular adhesion. Eur J Cancer 37:2264–2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Minna JD (2010) Non-small-cell lung cancer mRNA expression signature predicting response to adjuvant chemotherapy. JCO 28:4404–4407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Tomita Y, Hoshida Y et al (2006) Expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor is correlated with lymph node metastasis and prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 12:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Tomita Y, Hoshida Y et al (2007) Expression level of hepatoma-derived growth factor correlates with tumor recurrence of esophageal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 14:2141–2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Mao L (2006) SiRNA targeting hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) inhibits growth of non-small cell lung cancer in xenograft models. Tumor Biology 35: Emerging Molecules, Mechanisms, and Models. Proc Amer Assoc Cancer Res 47:abstract #5135

- Zhang J, Ren H, Yuan P, Lang W, Zhang L, Mao L (2006) Down-regulation of hepatoma-derived growth factor inhibits anchorage-independent growth and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res 66:18–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Qi J, Guo Y et al (2011a) Aberrant expression of HDGF and its prognostic values in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 14:211–218 (In Chinese) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Qi J, Guo Y (2011b) Abnormal expression and clinical significance of HDGF and ADAM9 in non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Yike Daxue Xuebao 40:280–281 (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Qi J, Chen N, Guo Y, Fu W, Zhou B, He A (2011c) Highly expressed ADAM9 in completed resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer cases predicts a shortened survival. J Thorac Oncol 6:s1068–s1069 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Chen N, Qi J (2013a) HDGF, ADAM9 involved in a novel pathway of cell growth and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells, may become novel molecular staging biomarkers, prognostic and predictive biomarkers of NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 8:s753 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Qi J, Chen N, Fu W, Zhou B, He A (2013b) High expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-9 predicts a shortened survival time in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 5:1461–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhou N, Fang W, Huo J (2010) Overexpressed HDGF as an independent prognostic factor is involved in poor prognosis in Chinese patients with liver cancer. Diagn Pathol 5:58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CQ, Ding K, Strumpf F et al (2010) Prognostic and predictive gene signature for adjuvant chemotherapy in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. JCO 28:4417–4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubel A, Flechtenmacher C, Edler L, Alonso A (2009) Expression of ADAM9 in CIN3 lesions and squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 114:332–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]