Abstract

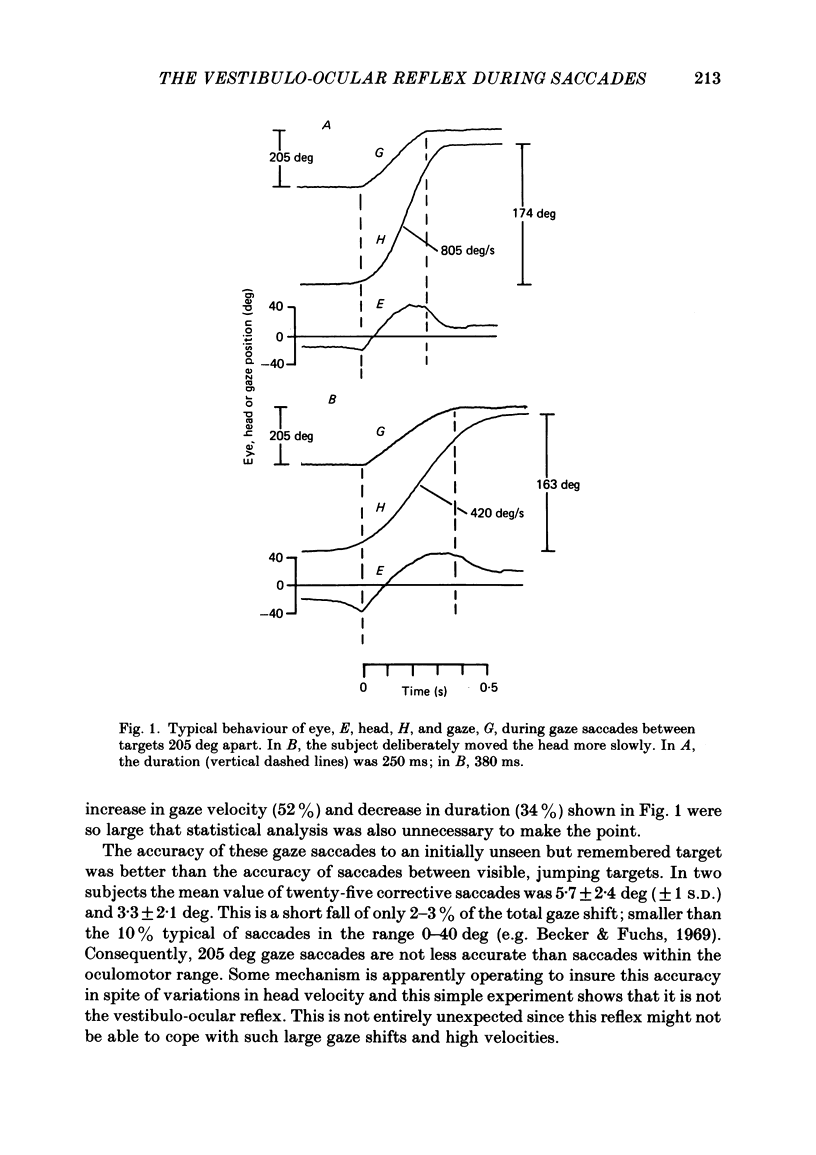

Eye and head movements were recorded in normal humans during rapid refixations with the head still (saccades) or moving (gaze saccades) to determine if the vestibulo-ocular reflex was operating at such times. Subjects made self-electrooculogram for large saccades and with the eyecoil/magnetic field method for smaller movements. The putative function of the vestibulo-ocular reflex during a gaze saccade is to adjust the movement of the eye for the movement of the head by adding the saccadic command and the vestibular signal. This action, referred to here as linear summation, would maintain gaze-saccade accuracy by making gaze velocity (eye in space) independent of head velocity. It would also preserve the duration of the eye saccades of about 200 deg. When a subject increased his head velocity voluntarily, for example, from 420 to 805 deg/s, mean gaze velocity rose from 540 to 820 deg/s and duration dropped from 380 to 250 ms. Linear summation did not occur. By means of a yoke clenched in the teeth, the subject's head could be momentarily and unexpectedly slowed by collision of the yoke with a lead weight during a 180 deg gaze saccade. The perturbation decreased head velocity by about 150-200 deg/s, decreased gaze velocity by about the same amount and did not change eye velocity (in the head); another indication that the vestibulo-ocular reflex was not working. Nevertheless, gaze-saccade duration was automatically increased so that the over-all accuracy of the movement was not changed. Subjects made saccades between targets at +/- 20 deg without attempted head movements. Simultaneously the experimenter struck the yoke, clenched in the subject's teeth, with a rubber hammer. The hammer blow caused a transient head velocity of about 70 deg/s. Gaze velocity transiently rose or fell, depending on the direction of the blow, by similar amounts and a quantitative analysis suggested that the vestibulo-ocular reflex was essentially absent. Again, duration was automatically altered so that saccade accuracy was not changed. Subjects looked back and forth between targets 20, 40 and 60 deg apart as their head turned through the straight ahead position, actively or passively, at velocities up to 600 deg/s (active) or 300 deg/s (passive).(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abel L. A., Dell'Osso L. F., Daroff R. B., Parker L. Saccades in extremes of lateral gaze. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979 Mar;18(3):324–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W., Fuchs A. F. Further properties of the human saccadic system: eye movements and correction saccades with and without visual fixation points. Vision Res. 1969 Oct;9(10):1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(69)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore C., Donaghy M. Co-ordination of head and eyes in the gaze changing behaviour of cats. J Physiol. 1980 Mar;300:317–335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A. F., Kaneko C. R., Scudder C. A. Brainstem control of saccadic eye movements. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1985;8:307–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller J. H., Maldonado H., Schlag J. Vestibular-oculomotor interaction in cat eye-head movements. Brain Res. 1983 Jul 25;271(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D., Douglas R. M., Volle M. Eye-head coordination in cats. J Neurophysiol. 1984 Dec;52(6):1030–1050. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.52.6.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henn V., Hepp K., Büttner-Ennever J. A. The primate oculomotor system. II. Premotor system. A synthesis of anatomical, physiological, and clinical data. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1(2):87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King W. M., Lisberger S. G., Fuchs A. F. Responses of fibers in medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) of alert monkeys during horizontal and vertical conjugate eye movements evoked by vestibular or visual stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1976 Nov;39(6):1135–1149. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso P., Bizzi E., Dichgans J. Adjustment of saccade characteristics during head movements. Exp Brain Res. 1973 Mar 19;16(5):492–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00234475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pola J., Robinson D. A. Oculomotor signals in medial longitudinal fasciculus of the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1978 Mar;41(2):245–259. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulaski P. D., Zee D. S., Robinson D. A. The behavior of the vestibulo-ocular reflex at high velocities of head rotation. Brain Res. 1981 Oct 5;222(1):159–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90952-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller P. H. The discharge characteristics of single units in the oculomotor and abducens nuclei of the unanesthetized monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1970;10(4):347–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02324764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D., Abel L. A., Dell'Osso L. F., Daroff R. B. Saccadic velocity characteristics: intrinsic variability and fatigue. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1979 Apr;50(4):393–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skavenski A. A., Hansen R. M., Steinman R. M., Winterson B. J. Quality of retinal image stabilization during small natural and artificial body rotations in man. Vision Res. 1979;19(6):675–683. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(79)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gisbergen J. A., Robinson D. A., Gielen S. A quantitative analysis of generation of saccadic eye movements by burst neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1981 Mar;45(3):417–442. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zee D. S., Optican L. M., Cook J. D., Robinson D. A., Engel W. K. Slow saccades in spinocerebellar degeneration. Arch Neurol. 1976 Apr;33(4):243–251. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500040027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]