Abstract

Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) formation is a trigger for the onset of age-related disease. To evaluate AGE-induced change in the ocular fundus, 5-mo-old C57BL/6 mice were given low-dose d-galactose (d-gal) for 8 wk and evaluated by AGE fluorescence, electroretinography (ERG), electron microscopy, and microarray analysis for 20 wk. Although AGE fluorescence was increased in d-gal-treated retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)–choroid compared with controls at all time points, ERG showed no AGE-induced functional toxicity. Progressive ultrastructural aging in the RPE–choroid was associated temporally with a transcriptional response of early inflammation, matrix expansion, and aberrant lipid processing and, later, down-regulation of energy metabolism genes, up-regulation of crystallin genes, and altered expression of cell structure genes. The overall transcriptome is similar to the generalized aging response of unrelated cell types. A subset of transcriptional changes is similar to early atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by matrix expansion and lipid deposition. These changes suggest an important contribution of a single environmental stimulus to the complex aging response.

Keywords: transcriptome, basal deposit, Brucha's membrane

Aging is a multifactorial process associated with physiological decline. Prior efforts to comprehensively identify and evaluate contributory factors have benefited from global assessment strategies such as microarray analysis. Although some general trends in the transcriptional responses to aging have been identified in diverse tissues such as skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and brain, the aging kidney is without modification (1–4).

Normal vision requires a functional retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)–Bruch's membrane (BM)–choroid to sustain the neurosensory retina. Photooxidative stress, photoreceptor outer segment shedding, lipid peroxidation, high metabolic requirements, and increased oxygen demand result in high levels of oxidative stress to the fundus. As a result, with aging, the RPE and choriocapillaris endothelium dedifferentiate (5, 6). The most significant changes are basal deposits that develop within BM, a pentalaminar matrix that includes the RPE and choriocapillaris endothelial basement membrane (5, 6). The location and composition of the deposits correlates with the development of age-related disease (5, 6). The molecular events surrounding basal deposit formation, however, are poorly characterized.

Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) are a heterogeneous group of reaction products that form between a protein's primary amino group and a carbohydrate-derived aldehyde group. A substantial amount of literature indicates that AGEs exacerbate and accelerate aging change and contribute to the early phases of age-related disease, including atherosclerosis, cataract, neurodegenerative disease, renal failure, arthritis, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (7, 8). We found that AGEs accumulate with age in human BM and immunolocalize to basal deposits (9–11). We recently identified AGE formation and ultrastructural aging in the RPE–choroid of mice treated with low-dose d-galactose (d-gal) (12). Using this stimulus, we seek to understand the AGE-induced molecular events that contribute to aging of the RPE–BM–choroid. After AGE induction, we assessed the transcriptional response in the RPE–choroid and compared it to known responses by nonocular tissues.

Our findings indicate that temporal transcriptional changes after AGE stimulus in the RPE–BM–choroid have substantial overlap with other general aging transcriptional changes. Notably, a subset of genes had expression changes in a pattern observed with atherosclerosis, a prototypical age-related disease. Insights into AGE biology resulting from this study of the RPE–BM–choroid microenvironment may apply broadly to situations in which specific aging factors combined with other known risk factors, exaggerate aging, and facilitate the transition to clinically apparent, age-related disease such as atherosclerosis or AMD.

Methods

Mice. All experiments were conducted according to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the research was approved by the institutional research board at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. C57BL/6 mice purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda) were fed standard rodent chow and water ad libitum and kept in a 12-h light–dark cycle. Mice (5 mo old; n = 10/group per time point) were given daily s.c. injections for 8 wk of either PBS or d-gal (50 mg/kg, Sigma) (12). Mice were killed at 4, 8, 12, and 20 wk.

Electroretinography. With the investigator masked to the treatment group, mice (n = 8 per group) were dark-adapted for a standardized 12-h period, and a- and b-wave recordings were obtained from both eyes for 11 intensity levels (-3 to 1.40 log cd·s/m2) by using an Espion ERG Diagnosys (Diagnosys, Littleton, MA). The data were log-transformed for normality, and a-wave and b-wave amplitudes were compared by ANOVA.

Tissue Preparation. After mice were killed and eyes were enucleated, one eye was fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.08 M cacodylate buffer for electron microscopy. The RPE–choroid of the contralateral eye was dissected and cryopreserved at -80°C for AGE and lipid peroxide assessment or placed in 600 μl of RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for transcriptional analysis.

AGE Fluorescence and Lipid Peroxide Production. Fluorescence of RPE–choroid samples was measured at excitation (ex) = 370 nm/emission (em) = 440 nm and cross-checked at ex = 330 nm/em = 390 nm to eliminate lipofuscin-related fluorescence, as described in ref. 12. Lipid peroxide content of hydrolysates at 8 wk was determined by using the xylenol orange method (PeroXoquant Quantitative Peroxide Assay Kit, Pierce) using an ELISA plate reader (Bio-Tek, Burlington, VT) at 595 nm. Fluorescence and peroxide concentration were normalized to hydroxyproline content, as determined with the Woessner assay.

Electron Microscopy. The central 2 × 2-mm tissue temporal to the optic nerve was postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide and dehydrated and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 resin (Polysciences). Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a JEM-100 CX electron microscope (JEOL).

Semiquantitative Grading System. The average BM thickness was determined from the thinnest and thickest measurements by a masked observer (13). The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the mean BM thickness in different groups. RPE and choriocapillaris ultrastructural changes and BM basal deposits (criteria including location, thickness, continuity, and content) were graded for severity and frequency by a masked observer using a modified protocol established by Cousins et al. (12, 14).

RNA Isolation. Tissue was homogenized with a QIAshredder spin column (Qiagen), and total RNA from the RPE–choroid was extracted by using the RNeasy Minikit (Qiagen). RNA quality was assessed with the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA).

Transcriptional Profiling by Oligonucleotide Microarray. Total RNA (50 ng) was reverse-transcribed with SuperScript II (0.5 μl, Invitrogen). Two cycles of T7 amplification were performed by using the Small Sample Labeling Assay, Version II (Affymetrix), and cRNA probe was biotinylated with the Affymetrix ENZO BioArray HighYield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit. Fragmented cRNA (10 μg) was hybridized onto a mouse MOE430A array containing 14,484 full-length genes (Affymetrix), and each array was scanned with the GeneArray scanner (Agilent Technologies). Scanned output files were analyzed with Affymetrix microarray suite 5.0 and normalized to an average intensity of 500 independently before comparison. To identify differentially expressed transcripts, pairwise comparison analyses were carried out with data mining tool 3.0 (Affymetrix). Nine pairwise comparisons for each gene (experimental, n = 3; control, n = 3) were performed. Transcripts with altered expression in at least seven of nine comparisons with ≥1.5-fold change were designated as differentially expressed and are reported as the average fold change in expression.

Real-Time RT-PCR. Total RNA (100 ng) was reverse-transcribed with Sensiscript (1 μl, Qiagen). Primer sequences were designed by using primer 3 (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA), and sequences were verified by using National Center for Biotechnology Information UniGene cluster IDs (see the supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site). Thermocycling (LightCycler, Roche Diagnostics) was performed in a 20-μl volume containing SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (10 μl, Qiagen), Primer A and B (0.5 μM each), and 2 μl of cDNA. PCR products were quantified by using lightcycler analysis software, checked by melting point analysis, and normalized to cyclophilin A mRNA expression. Experiments were repeated once and are reported as the average differential expression change.

Results

AGEs and Lipid Peroxidation Products Form in the RPE–Choroid Without Functional Toxicity. Compared with controls, AGE fluorescence at ex = 370 nm/em = 440 nm and ex = 330 nm/em = 390 nm was increased in d-gal-treated RPE–choroid (Fig. 1). d-gal treatment for 8 wk induced lipid peroxidation of the RPE–choroid (249.1 ± 68.8 μmol/μg) compared with controls (115.1 ± 30.1 μmol/μg; P = 0.039). Early AMD does not induce full-field electroretinography (ERG) changes (15). To assure that d-gal did not cause retinal toxicity, full-field ERGs showed no a- or b-wave amplitude or a- or b-wave implicit time abnormalities at all time points (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

AGEs increase with d-gal treatment. AGE fluorescence measured at ex = 370/em = 440 (Upper) and ex = 330/em = 390 (Lower) in the RPE–choroid was increased in d-gal-treated eyes (red) compared with controls (blue) at all time points.

d-gal Induces Ultrastructural Aging to the RPE–Choroid. The mean BM of d-gal-treated eyes increased in thickness over the study (0.24 ± 0.11 to 0.50 ± 0.036 μm) and was thicker than controls at all time points (P ≤ 0.18; see the supporting information). Control eyes at 4 wk showed a rare outer collagenous layer deposit, whereas d-gal-treated eyes had RPE with dilated and fewer basolateral infoldings and small outer collagenous layer deposits (Fig. 2). By 8 wk, d-gal RPE had severe dilation and loss of basolateral infoldings, basal laminar deposits with long-spacing collagen, and prominent outer collagenous layer deposits (Fig. 3). By 12 and 20 wk, control RPE had mildly dilated basolateral infoldings and outer collagenous layer deposits, but d-gal-treated eyes showed more severe changes than controls (Fig. 4).

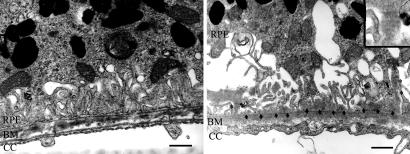

Fig. 2.

Early ultrastructural changes after d-gal treatment. At 4 wk, controls (Left) had normal RPE, BM, and choriocapillaris (cc), whereas d-gal-treated RPE–choroid (Right) had fewer and dilated basolateral infoldings and outer collagenous deposits (*). (Scale bar, 1 μm.)

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural aging after d-gal treatment. At 8 wk, control RPE–choroid appears unchanged in controls (Left), whereas d-gal-treated eyes (Right) had exaggerated dilation and loss of basolateral infoldings and basal laminar deposits (arrows) that contain long-spacing collagen (*). Choriocapillaris (CC) endothelium is without fenestrations. (Inset) A magnified image of long-spacing collagen. (Scale bar, 1 μm.)

Fig. 4.

Continued ultrastructural aging after d-gal treatment. At 20 wk, control RPE–choroid appears unaffected (Upper Left); d-gal-treated RPE–choroid (Upper Right) shows basal laminar deposit (arrows) and prominent outer collagenous layer deposit (*s). (Lower Left) A prominent basal laminar deposit (arrows) adjacent to an intercapillary region (*). (Upper Right) Lipid-like membranous vacuoles within the RPE. (Scale bar, 1 μm.)

The severity and frequency of ultrastructural aging was semiquantified by using a modified, established grading scale (12, 14). Although aging severity increased with time in controls, more severe changes were seen in d-gal-treated eyes at each time point. The aging severity in d-gal-treated eyes peaked at 8 wk and was similar thereafter. The frequency of ultrastructural aging was identical between groups at 4 wk. From 8 to 20 wk, ultrastructural aging was more frequent in d-gal-treated eyes than in control eyes. In particular, severe basal laminar deposits, outer collagenous layer deposits, and choriocapillaris endothelial changes were more frequent in d-gal-treated eyes than in control eyes (see the supporting information).

Differential Gene Expression of the RPE–Choroid by d-gal Treatment. At 4 wk, 39 genes were up-regulated and 42 genes were down-regulated by d-gal-treated RPE–choroid. Clusters of nine genes related to inflammation, eight genes related to matrix regulation, and six genes related to cell structure were differentially expressed (Table 1). At 8 wk, 22 genes were up-regulated and 30 genes were down-regulated by d-gal. A cluster of 10 genes related to cell structure, 9 genes related to lipid metabolism/transport, and 9 genes related to matrix regulation were identified (Table 2). Distinct gene expression changes continued after d-gal treatment. At 12 wk, 27 genes were up-regulated in d-gal treated eyes, of which 17 genes have function related to cell structure. At 20 wk, 18 genes were up-regulated and 29 genes were down-regulated by d-gal treatment. The expression of cell structure genes (n = 18) was altered; six energy metabolism genes were down-regulated, and five crystallins were up-regulated by d-gal (Table 3). Tables of all of the differentially expressed genes for each time point appear in the supporting information. To validate the array expression, 19 genes were evaluated by real-time RT-PCR, and all were found to be in agreement with the arrays (Table 4).

Table 1. Genes differentially expressed by the RPE–choroid after 4 wk of d-gal treatment.

| Gene | UniGene cluster ID | Fold change, d-gal/control | Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myh3 | Mm.2780 | 3.2 | Cell structure |

| Tpm3 | Mm.17306 | 2.3 | Cell structure |

| Eva | Mm.33240 | 2.0 | Cell structure |

| Myh2 | Mm.34425 | 1.5 | Cell structure |

| Cldn5 | Mm.22768 | –2.9 | Cell structure |

| Mbp | Mm.2992 | –4.3 | Cell structure |

| PAI1 | Mm.1263 | 1.9 | ECM; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Fmod | Mm.41573 | 1.8 | ECM; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Fbln1 | Mm.219663 | 1.7 | ECM |

| TGF-β2 | Mm.18213 | 1.8 | ECM; matrix regulation |

| Fbln3 EFEMP1 | Mm.44176 | 1.5 | ECM; Malattia Leventinese gene |

| Cspg2 | Mm.4575 | 1.5 | ECM; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Cst3 | Mm.4263 | –2.7 | ECM; involved in atherosclerosis |

| Pdgfr-β | Mm.4146 | –3.4 | ECM; matrix regulation; inflammation; atherosclerosis |

| Ifi202b | Mm.89990 | 7.8 | Inflammation; increased in atherosclerosis and apoptosis |

| Il-6 | Mm.1019 | 5.7 | Inflammation; aging; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Ptx3 | Mm.4663 | 4.7 | Inflammation; increased in atherosclerosis |

| CXCL2 | Mm.4979 | 4.1 | Inflammation; increased in atherosclerosis |

| CXCL1 | Mm.21013 | 3.5 | Inflammation; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Lcn2 | Mm.9537 | 2.7 | Inflammation; increased in atherosclerosis |

| Tnfrsf21 | Mm.200792 | 1.6 | Inflammation; apoptosis |

| Oasl2 | Mm.27162 | –2.6 | Inflammation; cell growth differentiation, and apoptosis |

| CEBPD | Mm.4639 | 1.6 | Inflammation transcription factor; induces inflammation genes |

Table 2. Genes differentially expressed by the RPE–choroid after 8 wk of d-gal treatment.

| Gene | UniGene cluster ID | Fold change, d-gal/control | Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myh3 | Mm.2780 | 3.7 | Cell structure |

| Pvrl3 | Mm.46724 | 2.2 | Cell structure |

| Cntn1 | Mm.4911 | 1.7 | Cell structure |

| Tnnt1 | Mm.711 | 1.5 | Cell structure |

| Tmsb10 | Mm.3532 | –1.9 | Cell structure |

| Bgpc | Mm.14114 | –2 | Cell structure; immune response |

| Ceacam1 | Mm.14114 | –2.5 | Cell structure; immune response |

| Sprr1a | Mm.625 | –3.5 | Cell structure |

| Mbp | Mm.2992 | –6.4 | Cell structure |

| Krt1–14 | Mm.6974 | –11.4 | Cell structure |

| Col18a1 | Mm.196000 | 1.8 | ECM |

| Col4a5 | Mm.155579 | 1.5 | ECM |

| Fbn1 | Mm.735 | 1.7 | ECM; Marfan's syndrome |

| Fmod | Mm.41573 | 1.5 | ECM |

| Dpt | Mm.28935 | 1.5 | ECM |

| ECM1 | Mm.3433 | –1.7 | ECM |

| Prpmp5 | Mm.4491 | –2.2 | ECM |

| Mmp3 | Mm.4993 | –2.9 | ECM |

| Prg4 | Mm.212696 | –3 | ECM; cell proliferation |

| Acrp30 | Mm.3969 | 5.4 | Inflammation |

| DF | Mm.4407 | 4.4 | Inflammation/lipid metabolism |

| Fabp4 | Mm.582 | 3.5 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Scd1 | Mm.140785 | 1.7 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Lpl | Mm.1514 | 1.5 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Apod | Mm.2082 | –1.9 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Cyp2f2 | Mm.4515 | –2 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Angptl4 | Mm.196189 | –2.1 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| Fabp5 | Mm.741 | –2.7 | Lipid metabolism/processing |

| S100a8 | Mm.21567 | –3 | Lipid metabolism/processing; FA–p34 complex |

| S100a9 | Mm.2128 | –4 | Lipid metabolism/processing; FA–p34 complex |

Table 3. Genes differentially expressed by the RPE–choroid 20 wk after d-gal treatment.

| Gene | UniGene cluster ID | Fold change, d-gal/control | Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krt2–6b | Mm.196352 | 6.4 | Cell structure |

| Eva | Mm.33240 | 2 | Cell structure |

| Scel | Mm.852 | 1.6 | Cell structure |

| Actn3 | Mm.5316 | –2.8 | Cell structure |

| Actc1 | Mm.686 | –2.9 | Cell structure |

| Mylpf | Mm.14526 | –3 | Cell structure |

| Tncs | Mm.1716 | –3.2 | Cell structure |

| Tnni2 | Mm.39469 | –3.2 | Cell structure |

| Acta1 | Mm.214950 | –3.2 | Cell structure |

| Mylf | Mm.1000 | –3.3 | Cell structure |

| Smpx | Mm.140340 | –3.5 | Cell structure |

| Ttid | Mm.143804 | –3.6 | Cell structure |

| Myhc-IIB | Mm.35531 | –3.7 | Cell structure |

| Myh2 | Mm.34425 | –4.1 | Cell structure |

| Tpm2 | Mm.121878 | –4.5 | Cell structure |

| Trdn | Mm.55320 | –4.6 | Cell structure |

| Ldb3 | Mm.29733 | –5.2 | Cell structure |

| Myh3 | Mm.2780 | –7.1 | Cell structure |

| Pdha1 | Mm.34775 | –2.4 | Energy metabolism |

| Ckmm | Mm.2375 | –3.1 | Energy metabolism |

| Eno3 | Mm.29994 | –3.3 | Energy metabolism |

| Adss1 | Mm.3440 | –3.5 | Energy metabolism |

| Ckmt2 | Mm.20240 | –4.8 | Energy metabolism |

| Pgam2 | Mm.219627 | –14.5 | Energy metabolism |

| Crygs | Mm.6253 | 4.3 | Crystallin; stress response |

| Cryba1 | Mm.22830 | 4.1 | Crystallin; stress response |

| Cryaa | Mm.1228 | 3.7 | Crystallin; stress response |

| Cryba4 | Mm.40324 | 3.4 | Crystallin; stress response |

| Crybb2 | Mm.1215 | 3.3 | Crystallin; stress response |

Table 4. Differential expression of selected genes by real-time RT-PCR.

| Gene | Time, wk | Change array | Change RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Il6 | 4 | 5.7 | 7.2 |

| Ptx3 | 4 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

| CXCL1 | 4 | 3.5 | 2.4 |

| Cldn5 | 4 | –2.9 | –3.7 |

| Fbn3 | 4 | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| Acrp30 | 8 | 5.4 | 3.5 |

| DF | 8 | 5.3 | 9.1 |

| Angptl4 | 8 | –2.1 | –4.2 |

| FABP4 | 8 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| FABP5 | 8 | –2.7 | –2.0 |

| LPL | 8 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| MMP3 | 8 | –2.9 | –3.2 |

| S100A8 | 8 | –3.0 | –2.6 |

| S100A9 | 8 | –4.0 | –2.6 |

| SCD1 | 8 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Acta1 | 12 | 2.6 | 4.3 |

| Crbaa | 20 | 3.7 | 6.7 |

| Cryba3 | 20 | 4.1 | 6.7 |

| Crbb2 | 20 | 3.3 | 3.9 |

Fold change is expressed as d-gal/control.

Discussion

Genetic and environmental factors influence physiological degradation associated with aging. The transcriptional response of the RPE–choroid in vivo to environmental factors is poorly understood. Because we previously demonstrated an age-dependent increase of AGEs in human BM and because glycoxidation modifications have been identified in the RPE with aging and AMD (10, 16, 17), we evaluated global gene expression changes after this single environmental stimulus on aging with the goal of identifying environmentally induced transcriptional susceptibility for aging and age-related disease. With progressive ultrastructural changes after an AGE stimulus to the RPE–BM–choroid that mimic human aging, we associate these sequential transcriptional changes consisting of inflammation, matrix expansion, and altered lipid metabolism/processing and subsequent modifications to cell structure, reduced energy metabolism, and increased stress response. These alterations are both similar to the chronological aging response by diverse cell types and include clusters of susceptibility for age-related disease. This transcriptional response underscores the potential relevance of studying a single environmental factor in the context of aging.

Our results show a global transcriptional response after AGE stimulus by the RPE–choroid that has significant similarity to the generalized aging response of brain, skeletal, and cardiac muscle, including increased inflammation, reduced metabolism and biosynthesis, and increased stress response (1–3). Because these tissues are partially composed of postmitotic cells like the RPE, these overlapping transcriptional features may be common to cells that have limited regenerative capacity after insult. The similarity in response of the RPE–choroid, brain, and muscle suggests that AGEs contribute to aging more than previously recognized.

Within each aging profile are unique changes related to the tissue demands of each microenvironment. For example, the aging cardiac myocyte shifts from a predominantly lipid to carbohydrate-dependent metabolism, which is the opposite of aging skeletal muscle (1, 2). Likewise, in the RPE–choroid, a cluster of energy metabolism genes were down-regulated and four stress response crystalline genes were up-regulated by d-gal. The crystallins are increased as a general stress response in many cell types, but in the RPE–choroid, they may have particular importance because they prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (18, 19). The four crystallins (β-A3, β-A4, β-B2, and β-S) up-regulated by d-gal have been identified as the most common proteins identified in drusen from AMD samples (20). The crystallins are ideal defense molecules in an energy-deficient cell because they don't require ATP while preventing stress-induced protein aggregation (21). We interpret this expression pattern as a protective response to d-gal protein modifications in an energy-deficient cell.

A subset of the transcriptional response by the RPE–choroid is reminiscent of the “response-to-retention hypothesis” of atherosclerosis, where lipoprotein cholesterol retention and oxidative modification in the vascular intima initiate both chronic inflammation and matrix expansion (22). All of the inflammatory genes that were up-regulated by d-gal in the RPE–choroid are up-regulated in atherosclerosis, potentially linking AGEs with inflammation, atherosclerosis, and BM aging associated with AMD. Mechanistically, it is possible that this inflammatory cascade is induced by the up-regulation of CEBPD, which activates inflammation in atherosclerosis (23). IL-6 up-regulation induces oxidative stress, promotes dyslipidemia, and increases C-reactive protein (CRP), an established cardiovascular disease marker (24, 25) that has recently been associated with AMD (26). The up-regulation of the long pentraxin PTX-3, which shares homology to CRP, activates complement in atherosclerotic plaques (27). Complement accumulates both in BM with AMD (28, 29). A role for complement in our model is suggested by up-regulation of DF (complement factor D), which also accumulates in atherosclerotic plaques (28). The up-regulation of the inflammatory genes Ifi202b, TNFRSF21, and Lcn2 all induce apoptosis in atherosclerosis and could promote RPE apoptosis, a recognized mechanism of RPE cell loss during aging and AMD (30–37). We interpret this transcriptional response as a local inflammatory response that is triggered, in part, by AGE formation.

Analogous to the arterial wall in atherosclerosis, aging BM accumulates heterogeneous debris known as basal deposits. Early deposit formation is the result of normal basement membrane component expansion (38–40). Further evidence of overlap between d-gal-induced transcriptional changes in the RPE–choroid and atherosclerosis is the altered expression of matrix genes. d-gal and atherosclerosis are both characterized by up-regulation of Cspg2, Fmod, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and Fbln-1 and -3 and down-regulation of Cst-3 and matrix metalloproteinase type 3 (41–44). Fbln-3 (EFEMP1) associates with drusen in AMD (45), and Fbln-3 mutations are linked to Malattia Leventinese, a macular dystrophy with a phenotype that is remarkably similar to AMD (46). Interestingly, an allelic variant of Cst-3 has also been associated with AMD (47). d-gal also altered a cluster of matrix genes that differed from those in atherosclerosis, including the up-regulation of Col4a5, Col18a1, Fmod, Fbn-1, and Dpt, which highlights the complexity of matrix expansion.

Cholesterol deposition in the inner collagenous layer is an important antecedent event of basal linear deposits, the most specific basal deposit for AMD (48). Recent evidence supports local lipoprotein secretion by the RPE into BM (49, 50). d-gal-related transcriptional changes involving intracellular lipid transport (i.e., fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) 4 and 5 and the FA–p34 complex), cholesterol esterification [stearoyl CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1)], and extracellular lipid processing [lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and Angptl4) all play a critical role in atherosclerosis and could promote lipoprotein secretion by the RPE with subsequent retention in BM. For example, the cytoplasmic FABPs facilitate fatty acid uptake and intracellular fatty acid transport, which would increase fatty acid accumulation and promote their delivery for lipoprotein assembly (51, 52). In monocytes, the accumulation of cholesterol esters is a critical event in atherosclerosis that is regulated by FABP4, in part through up-regulation of IL-6 (53, 54), whereas in adipocytes, total FABP4 and FABP5 content controls the degree of fatty acid accumulation (53, 55). We also identified altered expression of the FA–p34 complex of S100A8 and S100A9, another intracellular fatty acid transporter (56) that regulates cell structure, proliferation, differentiation, and inflammation (57). SCD-1 is the rate-limiting microsomal enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids into phospholipids, triglycerides, and cholesterol esters, thereby preventing the toxic accumulation of free cholesterol (58) and stimulating lipoprotein assembly and secretion (59). LPL promotes lipid entry into cells, which would be enhanced by the down-regulation of Angptl4 through its inhibition on LPL activity (60). LPL also retains lipoproteins in the vascular wall by binding lipoproteins with Cspg2 (see above discussion), which enhances lipid entry into cells (61, 62). Transgenic mice overexpressing LPL have increased lipid accumulation in cardiomyocytes and a dilated cardiomyopathy (63). The proatherogenic LPL activity could promote either lipid entry into the RPE or lipoprotein retention in BM. Due to the high oxidative stress microenvironment of the fundus, oxidation of accumulated lipids and subsequent RPE injury is a mechanism worth exploring.

The ultrastructural and transcriptional changes identified in this model simulate aging. Important age-related gene expression changes may not have been recognized because of the small sample size or the bias introduced with the array strategy. Further work characterizing the transcriptional response of the specific cell types involved is scientifically indicated, although it remains technically difficult to reliably separate RPE from choroidal cells, particularly in mice. Aging is associated with posttranscriptional modifications that are missed in a purely transcriptional analysis. This investigation, however, identifies multiple changes induced by AGEs in the RPE–choroid, suggests that AGEs trigger a cascade of events that accelerate the aging response, and identifies clusters of factors that predispose to vulnerability to early disease, such as AMD. An advantage of this model is that it can be superimposed in other aging-related models. Given the complex multifactorial nature of aging, this combinatorial approach merits further investigation. Finally, the results of this study may have application to other complex age-related diseases as specific environmental and genetic influences are elucidated. For example, although genetic predisposition influences age-related diseases like AMD and atherosclerosis, similar gene expression responses induced by a single environmental stimulus such as AGEs underscore the importance of understanding generalizable aging pathways for age-related disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY 14055 (to J.T.H.), EY134020-04 (to P.G.), and JDRFI 10-2001-412 (to P.G.); the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust (P.G.); the Michael Panitch Macular Degeneration Research Fund (J.T.H.); gifts from Aleda Wright (to J.T.H.) and Rick and Sandy Forsythe (to J.T.H.); and an unrestricted award from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) to the Wilmer Eye Institute. J.T.H. is the recipient of a Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award from RPB.

Author contributions: P.G. and J.T.H. designed research; J.T., Kazuki Ishibashi, Kazuko Ishibashi, K.R., R.G., S.B., P.G., and J.T.H. performed research; K.R. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.T., Kazuki Ishibashi, K.R., R.G., S.B., P.G., and J.T.H. analyzed data; and J.T., Kazuki Ishibashi, P.G., and J.T.H. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: AGE, advanced glycation endproduct; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; d-gal, d-galactose; BM, Bruch's membrane; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; ECM, extracellular matrix; ex, excitation; em, emission; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; FABP, fatty acid-binding protein.

References

- 1.Lee, C. K., Allison, D. B., Brand, J., Weindruch, R. & Prolla, T. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14988-14993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, C. K., Klopp, R. G., Weindruch, R. & Prolla, T. A. (1999) Science 285, 1390-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee, C. K., Weindruch, R. & Prolla, T. A. (2000) Nat. Genet. 25, 294-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preisser, L., Houot, L., Teillet, L., Kortulewski, T., Morel, A., Tronik-Le Roux, D. & Corman, B. (2004) Biogerontology 5, 39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green, W. R. & Enger, C. (1993) Ophthalmology 100, 1519-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarks, S. H. (1976) Br. J. Ophthalmol. 60, 324-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownlee, M. (1995) Annu. Rev. Med. 46, 223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vingerling, J. R., Dielemans, I., Bots, M. L., Hofman, A., Grobbee, D. E. & de Jong, P. T. (1995) Am. J. Epidemiol. 142, 404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farboud, B., Aotaki-Keen, A., Miyata, T., Hjelmeland, L. M. & Handa, J. T. (1999) Mol. Vis. 5, 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handa, J. T., Verzijl, N., Matsunaga, H., Aotaki-Keen, A., Lutty, G. A., te Koppele, J. M., Miyata, T. & Hjelmeland, L. M. (1999) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40, 775-779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda, S., Farboud, B., Hjelmeland, L. M. & Handa, J. T. (2001) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 2419-2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ida, H., Ishibashi, K., Reiser, K., Hjelmeland, L. M. & Handa, J. T. (2004) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 2348-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dithmar, S., Curcio, C. A., Le, N. A., Brown, S. & Grossniklaus, H. E. (2000) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2035-2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cousins, S. W., Espinosa-Heidmann, D. G., Alexandridou, A., Sall, J., Dubovy, S. & Csaky, K. (2002) Exp. Eye Res. 75, 543-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson, G. R., McGwin, G., Jr., Phillips, J. M., Klein, R. & Owsley, C. (2004) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 3271-3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu, X., Meer, S. G., Miyagi, M., Rayborn, M. E., Hollyfield, J. G., Crabb, J. W. & Salomon, R. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42027-42035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schutt, F., Bergmann, M., Holz, F. G. & Kopitz, J. (2003) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 3663-3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alge, C. S., Priglinger, S. G., Neubauer, A. S., Kampik, A., Zillig, M., Bloemendal, H. & Welge-Lussen, U. (2002) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 3575-3582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao, Y. W., Liu, J. P., Xiang, H. & Li, D. W. (2004) Cell Death Differ. 11, 512-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabb, J. W., Miyagi, M., Gu, X., Shadrach, K., West, K. A., Sakaguchi, H., Kamei, M., Hasan, A., Yan, L., Rayborn, M. E., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14682-14687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas, A. & Das, K. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42648-42657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams, K. J. & Tabas, I. (1995) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 551-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takata, Y., Kitami, Y., Yang, Z. H., Nakamura, M., Okura, T. & Hiwada, K. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris, T. B., Ferrucci, L., Tracy, R. P., Corti, M. C., Wacholder, S., Ettinger, W. H., Jr., Heimovitz, H., Cohen, H. J. & Wallace, R. (1999) Am. J. Med. 106, 506-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber, S. A., Sakkinen, P., Conze, D., Hardin, N. & Tracy, R. (1999) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 2364-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seddon, J. M., Gensler, G., Milton, R. C., Klein, M. L. & Rifai, N. (2004) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 291, 704-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rolph, M. S., Zimmer, S., Bottazzi, B., Garlanda, C., Mantovani, A. & Hansson, G. K. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, e10-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deppisch, R. M., Beck, W., Goehl, H. & Ritz, E. (2001) Kidney Int. Suppl. 78, S271-S277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hageman, G. S., Luthert, P. J., Victor Chong, N. H., Johnson, L. V., Anderson, D. H. & Mullins, R. F. (2001) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 705-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Del Priore, L. V., Kuo, Y. H. & Tezel, T. H. (2002) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 3312-3318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunaief, J. L., Dentchev, T., Ying, G. S. & Milam, A. H. (2002) Arch. Ophthalmol. 120, 1435-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding, Y., Wen, Y., Spohn, B., Wang, L., Xia, W., Kwong, K. Y., Shao, R., Li, Z., Hortobagyi, G. N., Hung, M. C. & Yan, D. H. (2002) Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 3290-3297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasof, G. M., Lu, J. J., Liu, D., Speer, B., Mongan, K. N., Gomes, B. C. & Lorenzi, M. V. (2001) Oncogene 20, 7965-7975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsblad, J., Gottsater, A., Persson, K., Jacobsson, L. & Lindgarde, F. (2002) Int. Angiol. 21, 173-179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elneihoum, A. M., Falke, P., Hedblad, B., Lindgarde, F. & Ohlsson, K. (1997) Atherosclerosis 131, 79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devireddy, L. R., Teodoro, J. G., Richard, F. A. & Green, M. R. (2001) Science 293, 829-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu, S. T., Lin, H. J., Huang, H. L. & Chen, Y. H. (1998) J. Pept. Res. 52, 390-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newsome, D. A., Hewitt, A. T., Huh, W., Robey, P. G. & Hassell, J. R. (1987) Am. J. Ophthalmol. 104, 373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leu, S. T., Batni, S., Radeke, M. J., Johnson, L. V., Anderson, D. H. & Clegg, D. O. (2002) Exp. Eye Res. 74, 141-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Schaft, T. L., Mooy, C. M., de Bruijn, W. C., Bosman, F. T. & de Jong, P. T. (1994) Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 232, 40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wight, T. N. & Merrilees, M. J. (2004) Circ. Res. 94, 1158-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strom, A., Ahlqvist, E., Franzen, A., Heinegard, D. & Hultgardh-Nilsson, A. (2004) Histol. Histopathol. 19, 337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schafer, K., Muller, K., Hecke, A., Mounier, E., Goebel, J., Loskutoff, D. J. & Konstantinides, S. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 2097-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphries, S. E. & Morgan, L. (2004) Lancet Neurol. 3, 227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marmorstein, L. Y., Munier, F. L., Arsenijevic, Y., Schorderet, D. F., McLaughlin, P. J., Chung, D., Traboulsi, E. & Marmorstein, A. D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13067-13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stone, E. M., Lotery, A. J., Munier, F. L., Heon, E., Piguet, B., Guymer, R. H., Vandenburgh, K., Cousin, P., Nishimura, D., Swiderski, R. E., et al. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zurdel, J., Finckh, U., Menzer, G., Nitsch, R. M. & Richard, G. (2002) Br. J. Ophthalmol. 86, 214-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curcio, C. A., Millican, C. L., Bailey, T. & Kruth, H. S. (2001) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 265-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malek, G., Li, C. M., Guidry, C., Medeiros, N. E. & Curcio, C. A. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 413-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, C. M., Presley, J. B., Zhang, X., Dashti, N., Chung, B. H., Medeiros, N. E., Guidry, C. & Curcio, C. A. (2005) J. Lipid Res. 46, 628-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen, G. W., Liu, J. W. & De Leon, M. (2000) Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 76, 315-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy, E. J., Barcelo-Coblijn, G., Binas, B. & Glatz, J. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34481-34488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Makowski, L., Boord, J. B., Maeda, K., Babaev, V. R., Uysal, K. T., Morgan, M. A., Parker, R. A., Suttles, J., Fazio, S., Hotamisligil, G. S. & Linton, M. F. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 699-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fu, Y., Luo, N. & Lopes-Virella, M. F. (2000) J. Lipid Res. 41, 2017-2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hertzel, A. V., Bennaars-Eiden, A. & Bernlohr, D. A. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 2105-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siegenthaler, G., Roulin, K., Chatellard-Gruaz, D., Hotz, R., Saurat, J. H., Hellman, U. & Hagens, G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9371-9377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donato, R. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1450, 191-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ntambi, J. M. & Miyazaki, M. (2004) Prog. Lipid Res. 43, 91-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyazaki, M., Kim, Y. C., Gray-Keller, M. P., Attie, A. D. & Ntambi, J. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30132-30138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshida, K., Shimizugawa, T., Ono, M. & Furukawa, H. (2002) J. Lipid Res. 43, 1770-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olin, K. L., Potter-Perigo, S., Barrett, P. H., Wight, T. N. & Chait, A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34629-34636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Auerbach, B. J., Bisgaier, C. L., Wolle, J. & Saxena, U. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1329-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yokoyama, M., Yagyu, H., Hu, Y., Seo, T., Hirata, K., Homma, S. & Goldberg, I. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4204-4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.