Short abstract

Patients often ask how population risk data apply to them. This analysis will help doctors to answer that question for women considering hormone replacement therapy

The risk of breast cancer arises from a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors. Recent studies show that type and duration of use of hormone replacement therapy affect a women's risk of developing breast cancer.1-7 The women's health initiative trial was stopped early because of excess adverse cardiovascular events and invasive breast cancer with oestrogen and progestogen.6 The publicity increased public awareness of the risks of hormone replacement therapy, and this was heightened by the publication of the million women study.2 However, the recently published oestrogen only arm of the women's health initiative trial suggests that this formulation may reduce the risk of breast cancer.8 To help make sense of the often confusing information,9 women and clinicians need individual rather than population risk data. We have produced estimates that can be used to calculate individual risk for women living up to the age of 79 and suggest the risk may be lower than is often thought.

Importance of individual data

Fears about the risks of hormone replacement therapy have resulted in reduced use.10-12 Without individual risk data, however, it is difficult to weigh the benefits and harms of treatment accurately, and many women may have stopped treatment unnecessarily.

Although data on the lifetime risk of breast cancer (from birth to average life expectancy) are available, these are of limited value in the clinical context. This is because cumulative absolute risk declines as years of remaining life diminish, even though the age specific risk increases.13 The influence of hormone replacement therapy and other factors on absolute risk may be less in an elderly population because the number of years remaining at risk is fewer than in a younger population.

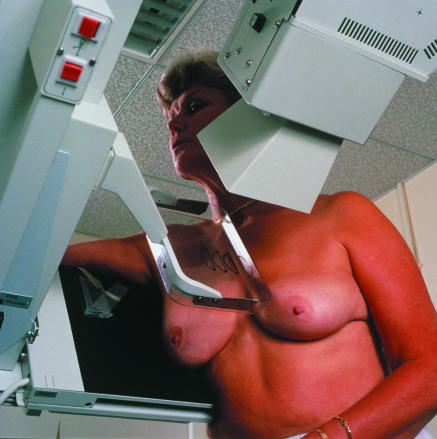

Figure 1.

Risk from hormone replacement therapy increases with duration of treatment

Credit: CHRIS PRIEST/SPL

Calculation of risk

We used the attributable fraction method to estimate the cumulative absolute risk of breast cancer from various ages to 79 years (average life expectancy) in relation to hormone replacement therapy. This technique has been used to calculate the risks of disease for breast cancer related to family history13 and for smokers and non-smokers14,15 and is described in more detail elsewhere.16,17

Our calculations are based on existing data on use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer. We estimated the use of hormone replacement therapy from the latest quinquennial Australian health survey (in 2001). We extrapolated the data to provide estimates of proportion and duration of use (no use, < 1 year, 1-5 years, 6-10 years, ≥ 10 years) for the entire Australian population by five year age group. In 2001, 11.7% of women (aged 18-80) were taking hormone replacement therapy, with highest use in 55-59 year olds (38%). Over two thirds of these women had been taking hormone replacement therapy for at least five years (see table A on bmj.com).

The annual incidence of breast cancer in Australia is about 11 000 new cases a year, of which over 4000 are diagnosed in New South Wales. We retrieved incidence data from the Cancer Council New South Wales website (www.nswcc.org.au). Previous studies have estimated the “underlying” incidence of breast cancer and the incidence attributable to breast screening.13,18 We applied these age specific screening effects to derive the 2001 underlying breast cancer incidence and the cumulative breast cancer risk of the population to age 79 years (table B on bmj.com). We then used data from the million women study (table C on bmj.com)2,5,6 to provide specific relative risks according to type of hormone replacement therapy and duration of use.

The attributable factor (AF) is the proportion of the disease due to a particular factor. We calculated the attributable factor for hormone replacement therapy in breast cancer for each age group by the indirect method19 from the specific prevalence and proportions of use and type of hormone replacement therapy20,21 and the published relative risk (RR) of breast cancer by type and duration of use.2

|

where p = prevalence of use × proportion using relevant type of hormone replacement therapy.

The attributable factors specific for type and duration of use of hormone replacement therapy for each age group can be summed and applied to a population. We calculated the breast cancer incidence and cumulative absolute risk in never users of hormone replacement therapy (Inever) from the underlying incidence of breast cancer in New South Wales (Ipop) using the direct method.19

|

We estimated the age specific breast cancer incidence for women who had never taken hormone replacement therapy and applied relative risks (from the million women study2). These incidences were summed and converted to cohort probabilities as cumulative risks over particular age ranges.16

|

We calculated cumulative risks from decade and mid-decade ages to age 79 years, roughly the life expectancy at birth of Australian women at the beginning of the 21st century.

Size of risk

The average baseline risk (from 40 to 79 years) is about 7.2% (1 in 14), reducing to 6.1% (1 in 16) at 50 years, and 4.4% (1 in 23) at 60 years (table). Use of oestrogen only hormone replacement or short term (about five years) use of combined therapy starting at age 50 years hardly affects the cumulative breast cancer risk calculated to the age of 79 (no use 6.1%, oestrogen only 6.3%, combined 6.7%). Use of combined hormone replacement therapy for about 10 years increases the cumulative risk to 7.7%.

Table 1.

Cumulative absolute risk and additional risk of breast cancer with duration of use of hormone replacement therapy

|

Age at calculation (years)

|

Age range (years)

|

Risk with no hormone replacement therapy

|

Additional risk (%) with combination therapy*(years of use)

|

Additional risk (%) with oestrogen only therapy*(years of use)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio† | % | 3 years | 5 years | 10 years | 15 years | 3 years | 5 years | 10 years | 15 years | ||

| 40 | 40-79 | 1 in 14 | 7.21 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 1.18 | 2.22 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.64 |

| 45 | 45-79 | 1 in 15 | 6.76 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 1.45 | 2.54 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.73 |

| 50 | 50-79 | 1 in 16 | 6.10 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 1.59 | 2.82 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.81 |

| 55 | 55-79 | 1 in 19 | 5.30 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 1.76 | 3.17 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.91 |

| 60 | 60-79 | 1 in 23 | 4.44 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 2.01 | 3.51 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.57 | 1.00 |

| 65 | 65-79 | 1 in 29 | 3.48 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 2.19 | 3.27 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.91 |

| 70 | 70-79 | 1 in 42 | 2.37 | 0.47 | 0.88 | 1.84 | — | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.50 | — |

| 75 | 75-79 | 1 in 88 | 1.14 | 0.43 | 0.58 | — | — | 0.12 | 0.14 | — | — |

The additional risk for a specific formulation and duration of use can be added to the baseline risk with no hormone therapy to provide an estimate of a woman's specific cumulative absolute risk of breast cancer from a specific age to age 79 years.

The ratio is calculated as the reciprocal of the cumulative absolute breast cancer risk (%) of non-users.

Oestrogen only formulations have a minimal effect on risk of breast cancer, even with extended use. A 55 year old woman has a cumulative absolute breast cancer risk to age 79 years of 5.3% (1 in 19). The additional risk is 0.2% with five years' use of oestrogen only hormone replacement therapy, 0.5% with 10 years, and 0.9% with 15 years.

The additional breast cancer risk is greater with combination therapy, especially if taken for more than five years. Five years' use, starting at age 55, generates an extra 0.6% breast cancer risk and 10 years a further 1.8% risk. Once hormone replacement therapy is stopped the relative risk quickly returns to 1.0 and the cumulative absolute risk of breast cancer returns to that of an age matched never user.

Applicability of estimates

Our derivation of absolute risk from a population incidence uses an established method.16 Application of the absolute risk to an individual assumes the woman is representative of the population from which the incidence data are drawn. The use of cumulative risks is similar to actuarial life table methods and is useful for quantifying what may happen to a hypothetical cohort if it passed through the age specific rates used in the calculations.

The relative risks of hormone replacement therapy that we used have been criticised for being overstated because of detection bias.9 They are similar, however, to those reported in recent trials, meta-analyses, and older cohort studies.1,4-6 The relative risk is not influenced by local incidence of breast cancer and thus should apply to an Australian population. Data from the million women study have small standard errors and allowed us to produce results according to formulation and duration of use. The study also showed that once hormone replacement therapy has been stopped, a woman's breast cancer risk quickly returns almost to 1.0.2 Therefore, a woman's cumulative absolute breast cancer risk returns to that of the population once treatment stops.

Summary points

Information about risk of breast cancer with hormone replacement therapy is conflicting

Data that can be used to derive individual risk are presented to help decision making

Cumulative absolute risk of breast cancer (to 79 years) falls with increasing age in women who do not take hormone replacement therapy

Use of hormone replacement therapy increases a woman's cumulative risk only slightly

The effect on the general incidence of breast cancer incidence would be greater

The data on use of hormone replacement therapy from the Australian health survey questionnaire are similar to those reported in UK, US, and European surveys.22-24 Although the survey did not identify the type of hormone replacement therapy used, other studies estimate one half of Australian, European, or American women taking hormone replacement therapy are taking combined preparations.2,20,21,25-27

Implications for use

Recent publicity has heightened anxiety about the risks of hormone replacement therapy, but absolute risk of developing breast cancer for an individual may not be as high as assumed. Stopping hormone replacement therapy early because of anxiety about the risks may reduce quality of life. Conversely, other women may underestimate their additional cancer risk and continue to take hormone replacement therapy.

Although we found the additional breast cancer risk with hormone replacement therapy for an individual is very small, the effect on the general incidence of breast cancer would be greater, especially in populations with a higher prevalence of use. The indications for hormone replacement therapy vary and decisions regarding its use must be made at an individual level. Our analysis provides women and clinicians with better information to make these choices.

Supplementary Material

Data used in the calculations are on bmj.com

Data used in the calculations are on bmj.com

The New South Wales Breast Cancer Institute receives funding from the New South Wales Department of Health. The Australian prevalence data were purchased from the Australian Health Survey 2001, Health Section, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia. We thank Greg Heard for his advice and detailed editorial help with the manuscript.

Contributors and sources: NJC participated in the writing, calculations, and editing of the article as principal investigator. RT contributed in the study design, analysis, and manuscript editing. NW provided editorial help and critical analysis. JB conceptualised the paper and contributed to the study design, writing, and editing. NJC is the guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 1995;332: 1589-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 2003;362: 419-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beral V, Banks E, Reeves G. Evidence from randomised trials on the long-term effects of hormone replacement therapy. Lancet 2002;60: 942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, Stefanick ML, Gass M, Lane D, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the women's health initiative randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289: 3243-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52 705 women with breast cancer and 108 411 women without breast cancer. Lancet 1997;350: 1047-59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288: 321-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schairer C, Lubin J, Troisi R, Sturgeon S, Brinton L, Hoover R. Menopausal estrogen and estrogen-progestin replacement therapy and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2000;283: 485-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T. The effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. The women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291: 1701-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro S. The million women study: potential biases do not allow uncritical acceptance of the data. Climacteric 2004;7: 3-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombs NJ, Boyages J. Changes in HRT prescriptions dispensed in Australia since 1992. Aust Fam Phys (in press). [PubMed]

- 11.MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. Hormone replacement therapy use over a decade in an Australian population. Climacteric 2002;5: 351-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med 2004;140: 184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor R, Boyages J. Absolute risk of breast cancer for Australian women with a family history. Aust NZ J Surg 2000;70: 725-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor R. Risks of premature death from smoking in 15-year-old Australians. Aust J Public Health 1993;17: 358-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor R. Estimating risk for tobacco-induced mortality from readily available information. Tobacco Control 1993;2: 18-23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day NE. Cumulative rate and cumulative risk. Cancer incidence in five continents. IARC Sci Publ 1992;120: 862-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornfield J. The estimation of the probability of developing a disease in the presence of competing risks. Am J Public Health 1957;47: 601-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor R, Boyages J. Estimating risk of breast cancer from population incidence affected by widespread mammographic screening. J Med Screening 2001;8: 73-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical methods in medical research. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1994.

- 20.MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH. Changes in use of hormone replacement therapy in South Australia. Med J Aust 1995;162: 420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLennan AH, MacLennan A, Wilson D. The prevalence of oestrogen replacement therapy in south Australia. Maturitas 1993;16: 175-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacs AJ, Britton AR, McPherson K. Utilisation of hormone replacement therapy by women doctors. BMJ 1995;311: 1399-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNagny SE, Wenger NK, Frank E. Personal use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy by women physicians in the United States. Ann Int Med 1997;127: 1093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson K, Mattsson L-A, Milsom I. Use of hormone replacement therapy. Lancet 1996;348: 1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olesen C, Steffensen FH, Sorensen HT, Nielsen GL, Olsen J, Bergman U. Low use of long-term hormone replacement therapy in Denmark. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999;47: 323-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen AT, Lidegaard O, Kreiner S, Ottesen B. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of non-fatal stroke. Lancet 1997;350: 1277-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brett KM, Madans JH. Use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: estimates from a nationally representative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145: 536-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.