Abstract

Purpose of Review

Drought is one of the most far-reaching natural disasters, yet drought and health research is sparse. This may be attributed to the challenge of quantifying drought exposure, something complicated by multiple drought indices without any designed for health research. The purpose of this general review is to evaluate current drought and health literature and highlight challenges or scientific considerations when performing drought exposure and health assessments.

Recent Findings

The literature revealed a small, but growing, number of drought and health studies primarily emphasizing Australian, western European, and U.S. populations. The selection of drought indices and definitions of drought are inconsistent. Rural and agricultural populations have been identified as vulnerable cohorts, particularly for mental health outcomes.

Summary

Using relevant examples, we discuss the importance of characterizing drought, and explore why health outcomes, populations of interest, and compound environmental hazards are crucial considerations for drought and health assessments. As climate and health research is prioritized, we propose guidance for investigators performing drought focused analyses.

Keywords: Drought, Exposure Assessment, Climate Change, Natural Disasters, Public Health

1. Introduction

The public health impacts of extreme weather and climate events are well documented [1,2]. The best studied natural disasters, such as heat waves [3–5], cyclonic storms [6–8], wildfires [9–11], and floods [12], tend to have abrupt onsets with noticeable high impact. These events develop rapidly and result in short-term acute effects with regionally persisting consequences. However, it is the slow to evolve and persistent drought that is considered the most far reaching natural disaster and a major contributor to climate-related health effects [13,14].

In the most basic sense, drought is a precipitation deficit resulting in water shortages that impact soil, hydrology, or water supply [15]. In the past 40 years, drought has likely impacted more people worldwide than any other natural disaster [16] and has caused an estimated 60% of all extreme weather deaths, despite representing only 15% of natural disasters [17]. In the United States, a 2012 pan-continental drought affected over 150 million people and covered nearly two thirds of the country [15,18,19], while California experienced its worst 3-year dry spell in 1,200 years from 2013–2015 [19,20]. Central South America had one of its most severe and prolonged drying spells from 2019–2022 that peaked with record breaking dry conditions over two standard deviations below normal soil moisture [21]. And from 2014–2018, Europe experienced a prominent and prolonged drought period that was exceptional not in annual severity, but for its 5-year duration that cost billions (€) in farming losses.[22] As an environmental hazard, drought exhibits a set of characteristics unique from other natural disasters. Drought is typically slow evolving and can persist across months and years with impacts that linger after an event has terminated [23]. Drought also has complex spatial and temporal boundaries, which can lead to disagreement over severity and extent [15,24–26]. As a society, there is a tendency to downplay the consequences of drought or overlook them entirely since these events rarely result in the highly visible structural damage typically associated with other natural disasters.

Drought causes adverse health outcomes through multiple direct and indirect pathways. Drought exacerbates harmful environmental exposures, including increased dust [27–29], extreme heat [30–32], wildfire prevalence and smoke [33–35], and changes in allergen composition [36,37]. Drought is perhaps best known for impacts on psychosocial stress and mental health [38–41]. Australian studies have identified drought events to be associated with increased stress, depression and suicide [39,42–46]. The largest mental health risks were observed in males from rural communities [42,45]. Persistent drought will even impact infectious disease, including modifying tick abundance in Lyme disease regions [47], Vibrio prevalence in estuarine environments [48,49], and the incidence of coccidioidomycosis, when drought follows wet conditions [50,51].

Our understanding of the detailed relationship between drought and health is still limited, despite its broad consequences [24,52,53]. A potential explanation for the paucity of drought and health research is the complexity of droughts as climatological events [54,55]. There is no standardized approach for measuring drought and consequently it is difficult to characterize factors of exposure, such as severity, duration, onset, and extent. Unlike tangible environmental hazards such as air pollution or extreme temperatures, drought is an ‘invisible’ phenomenon that cannot be directly measured with scientific instruments. Drought definitions also vary by region, such as Australian drought manifestation being different from midwestern U.S. drought, due to distinct characteristics in geography, climate systems, and water management practices. Consequently, drought metrics likely show varying associations with health outcomes. This same phenomenon has been observed with heatwave thresholds, where it has been argued that local heat definitions may better reflect risks for a given population [56]. Additionally, it is likely that drought exacerbates the health risks from other extreme weather events, such as dust storms, wildfires, and heat waves. Federal agencies and public health practitioners are tasked with creating appropriate drought early warning systems and risk mitigation plans; however, to effectively carry out this task it is crucial to understand the intricate characteristics of drought and how they affect health. The complexity of this problem underscores the need for multifaceted approaches to address this threat.

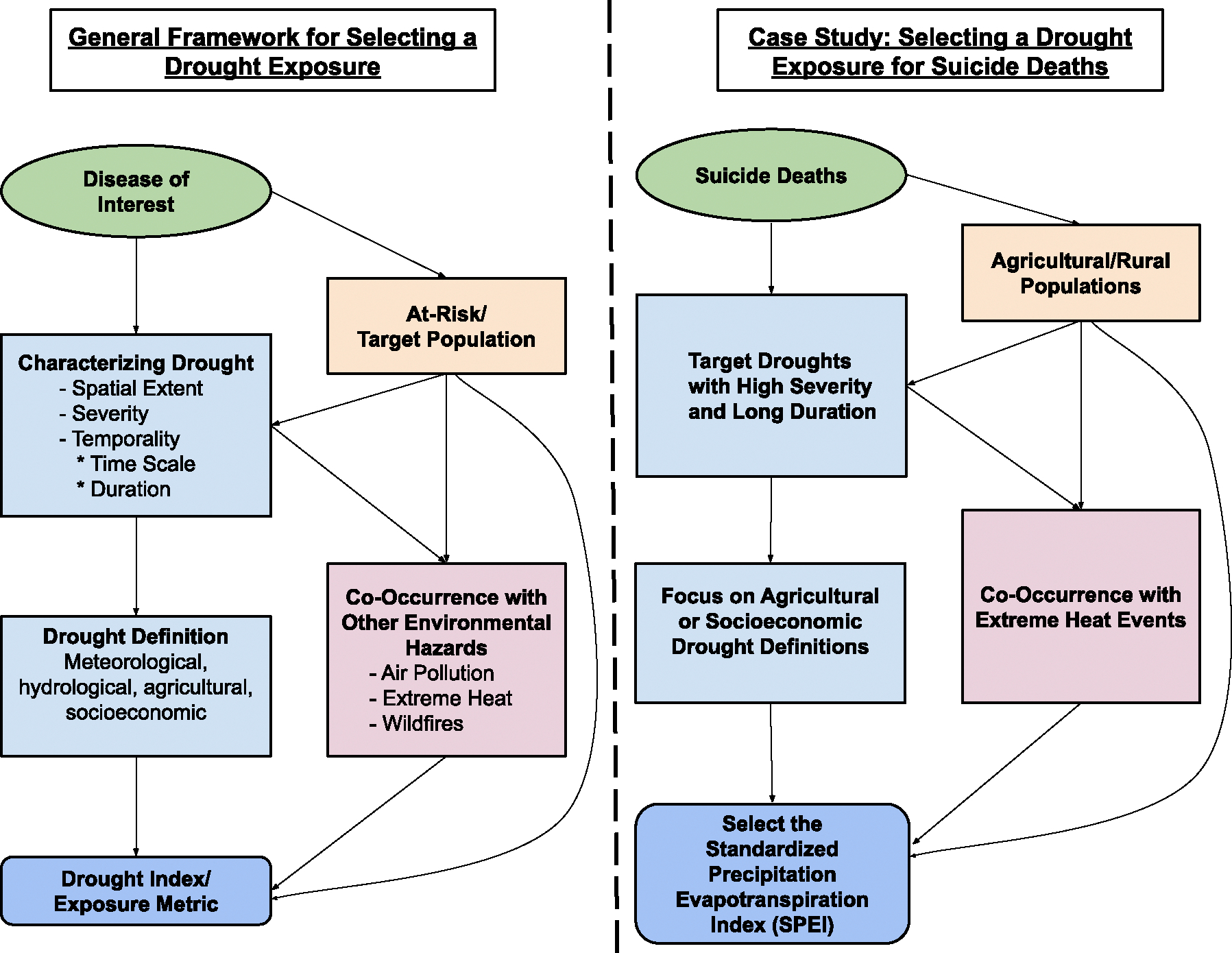

The objective of this integrative review is to examine recent literature and expand the discussion of challenges related to public health and drought research. We will emphasize the considerations that go into selecting a drought metric, including drought exposure characteristics, identifying at-risk populations, co-occurrence with other environmental hazards, and how these factors play into evaluating a disease. This approach is outlined in a conceptual framework to guide investigators performing drought and health epidemiological research (Fig 1). We illustrate some of these issues using U.S. drought data, provide relevant examples from the literature, and outline opportunities and new drought and health research needs.

Fig 1.

Guiding framework of factors to consider when performing drought and health research. The left side is a general framework for drought and health investigations, while the right side outlines the process using suicide as a case study.

2. Challenges in Characterizing Drought Exposure

A key challenge for assessing the health effects of drought lies with effective characterization of exposure. However, unlike air pollution or temperature, drought is not easily quantified. Instruments cannot directly measure drought, so meteorologists rely on atmospheric and environmental surrogates, such as precipitation, ground water, or soil moisture. Drought indicators combine multiple surrogates to compare current conditions against a long-term average or ‘normal,’ which is typically location specific, making drought in the arid southwestern United States different from drought in the humid southeastern United States [57]. Drought is additionally complicated by four unique types: meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and socio-economic droughts. These drought types are associated with a particular kind of water-related deficit. Meteorological drought is a lack of precipitation, agricultural drought is a lack of soil moisture to the extent that crop growth and production is negatively affected, hydrological drought is a measure of surface and groundwater availability, while socio-economic drought is defined as a negative supply related to water demand resulting in economic burden [25]. Socioeconomic drought is the most severe drought stage and considers the wider societal and economic impacts of prolonged meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological drought conditions. This type of drought can lead to water shortages for communities, increased competition for water resources, and significant economic losses in agriculture, industry, and other sectors. Other meteorological conditions, such as temperature, may exacerbate the severity and impacts of drought [23], while anthropogenic water use may amplify drought conditions [58,59].

The necessity of multiple drought definitions stems from the many stakeholders affected by drought conditions. Drought causes environmental, social, and economic impacts that can be local or far reaching. Therefore, a universally accepted drought definition has proved elusive, if not unobtainable. Currently around 150 drought indices exist, each designed to measure a specific phenomenon of drought with their own strengths and limitations [26,57,60]. No drought indices have been designed for human health research and there is no ‘best’ drought measure for epidemiological applications [15]. Therefore, selecting a drought exposure metric should rely on its ability to capture features that likely influence health-related vulnerability: severity, spatial extent, and temporality, including time scale and duration.

2.1. Severity of Drought

Severity of drought refers to the magnitude of a water deficit compared to normal conditions. It is frequently assessed and more severe drought has been associated with elevated mortality and disease [42,61–65]. However, drought metrics employ varying scales to quantify ‘severity’ and that complicates the comparison of health effects across studies. For example, in studies of drought and mortality, Berman et al. (2017) used exposures from the U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM) for their U.S. based study, which reports 5 categories of drought severity, while Salvador et al (2019) and Wang et al (2021) employed standardized precipitation indices (SPI) that report drought as standard deviations below or above the long-term precipitation mean for their studies in Spain and northwest China, respectively. While these three studies all examined the same exposure and health outcome, comparability and meta-analysis across them is complex as drought severity and magnitude was quantified so differently.

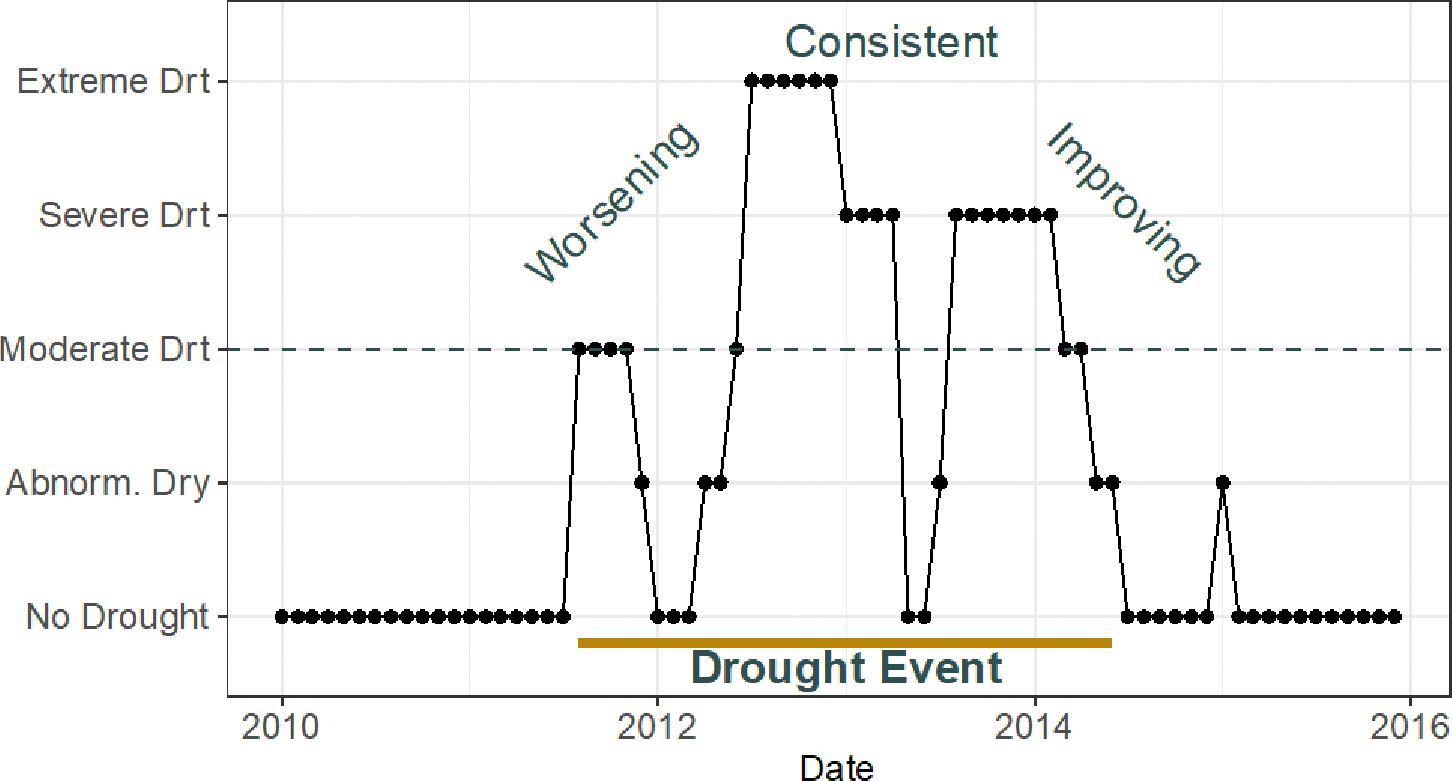

An additional consideration is that droughts are typically long-term events compared to other climate-related or meteorological disasters, where dry conditions begin, severity increases, and then improves back to baseline. A single drought event will therefore experience the same severity at least twice, which can add complexity to evaluating continuous exposure risk. In a randomly selected county, we demonstrate this phenomenon using USDM data for Jasper County, Iowa (Fig 2). In a 6-year time frame, we observe 3 separate drought periods that achieved moderate, severe, or extreme drought conditions (August 2011-November 2011; June 2012-April 2013; August 2013-April 2014), which may be considered a single long-term drought event. Moderate drought is recorded for both June 2012 and April 2013, but should these have the same health risk in the same drought event? June 2012 ‘moderate drought’ relates to early stages of the drought event, when environmental conditions are worsening, but individual and community resilience are still high. However, in April of 2013, the moderate drought condition represents the consequence of 11-months of continuous, yet now improving drought, and may be associated with far different health risks than moderate drought during the early portion of an event. Researchers have to carefully consider if a drought severity measure should be evaluated as a continuous environmental exposure [64,66] or if categorical events stratified by drought severity [61] with different worsening or improving conditions are more appropriate.

Fig 2.

U.S. Drought Monitor conditions for Jasper County, Iowa from 2010 through 2016. The dashed line highlights months with moderate drought conditions during this period.

2.2. Spatial Extent of Drought

Spatial extent refers to the total geographic area considered as a drought event. It may be an important exposure characteristic because larger droughts place greater demands on natural resources and human systems. However, there is little research looking at drought size and associated health risks. Measuring the extent of droughts may be complicated by the spatial resolution of drought data, which can range from data storage pixels to hydrologic watersheds to continuous spatial polygons. Dai (2011) discusses the challenges of deriving drought indices using data from multiple spatial scales, particularly with historical weather data where inputs can be missing or sparse [67]. Differences in data units for drought indices can make spatial comparisons of events difficult, notably in the transition between wet and dry conditions and at geographic margins [57]. From an epidemiological standpoint, the varying extents of drought events due to metric choice can lead to exposure misclassification and a bias toward the null.

2.3. Temporality of Drought: Timescale and Duration

The temporality of environmental hazards represents a key piece of the exposure assessment pathway. Observational studies, particularly for ubiquitous environmental hazards like air pollution or heat, rely on the precise evaluation of cumulative time-dependent exposures during a follow-up period [68]. However, evaluating drought requires the consideration of two time-related characteristics. First is the timescale of a drought condition. Drought is defined as current dryness compared to normal conditions, but ‘current’ could be interpreted as conditions over the past week, month, or even year. Dracup et al (1980) states “selection of the averaging period for a particular drought study is dependent almost entirely on the purpose for which the study is intended.” Most drought research commonly uses either 1-month, 3-month, 6 month, or 12-month intervals, which would capture short-term, seasonal, moderate, and long-term drought conditions [39,40,64,66,69]. However, interval choice has major consequences for the frequency, trend, and duration of drought over the same period of time.

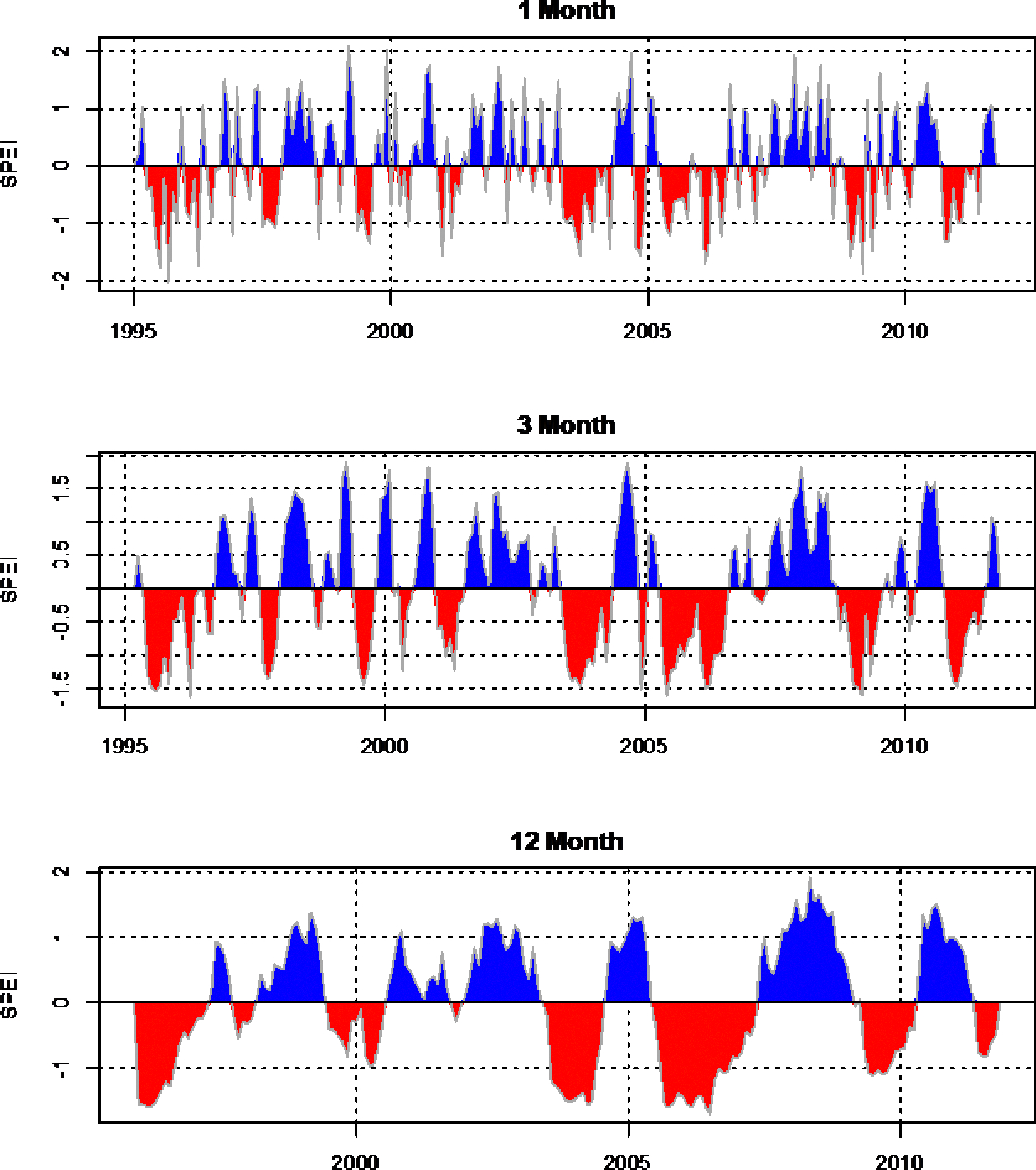

To highlight the phenomenon of drought time-scales, we pulled standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) for Wichita, Kansas from 1995 through 2012 at 1-, 3-, and 12-month time-scales (Fig 3) [70,71]. We observe that a 1-month timescale produces frequent drought measures of short duration with rapid fluctuation between wet and dry conditions, whereas timescales of 6- and 12-months have distinct events of longer duration. In choosing a drought timescale, researchers should consider the development of their disease and whether this depends on rapid or longer-term persistent drought.

Fig 3.

Drought conditions measured with the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) in Wichita, Kansas using timescales of 1-, 3-, and 12-months. Positive SPEI indicates wetter than normal conditions (blue) and negative SPEI indicates dryer than normal conditions (red).

The second time-related characteristic refers to the more familiar duration of exposure or length of a drought period. If we consider a time series of a drought index, estimating the duration of a drought exposure involves truncating our data into periods/events of drought and non-drought [72]. However, drought is complicated by its “creeping effect,” so that exact onset and termination is difficult to determine. Furthermore, depending on the drought definition or index, events can be out of sync with one another. Meteorological and agricultural droughts can develop in short time periods but can be lagged by hydrological or socioeconomic droughts as water deficits work their way through the system. During the same time period, a specific location may be considered a drought under one metric, but a non-drought using a different metric. This variability is further exacerbated by geographic location, where correlations between different drought measures may be impacted by local weather conditions such as cold-drought during winter conditions [73]. Drought requires us to consider not only severity, but factors related to the timing and duration of a drought event to effectively elucidate potential health risks.

3. Health Effects and Drought Exposure

Drought has been associated with several health effects, highlighting the multiple pathways to impact people and environment. In a systematic review, Stanke et al (2013) categorized drought health effects as 1) nutritional deficiencies, 2) water-related disease, 3) air-borne and dust related disease, 4) vector borne disease, 5) mental health effects, and 6) other outcomes, which include injury, heat waves and wildfires, migration, and infrastructure damage. Similar reviews have focused on comprehensive [55] and specific drought health effects, including mental health [24] and vector-borne disease [53]. Drought and human health was also an area of focus in the U.S. Global Change Research Program special report released in 2016 [74]. While these systematic reviews discuss many studies, a universal theme is that a comprehensive understanding of the drought and health relationship is still limited. Published research varies in study design and quality, and health effects from drought are likely under-recognized and under-reported. Limited papers quantify the direct association between drought and health, and separating effects from other environmental factors remains complex. Finally, defining drought exposures pertinent to specific health outcomes remains one of the largest challenges

Drought and vector-borne illness provides a useful example highlighting the importance of selecting a drought exposure based on the health outcome of interest. Studies have found that drought conditions amplify mosquito-borne encephalitis and West Nile virus [75–77]. The proposed mechanism is that reduced rainfall shrinks surface water, forcing avian hosts and mosquito vectors into a converged environment ideal for epizootic amplification. There is also evidence that drought can lead to dehydration in mosquitoes, which increases their feeding [78]. After a drought ends, the infected mosquitoes and birds will rapidly disperse and escalate disease transmission to humans [77,79,80]. Therefore, an investigation of drought and West Nile virus would choose a drought definition that captures surface water availability. A long-term hydrological drought index might be preferred, as it would best reference the availability of standing water (e.g. ponds, marshes) necessary for avian hosts. Had an agricultural or meteorological drought measure been selected, our exposure index would emphasize soil moisture and plant growth, which are not as useful for understanding mosquito populations. A second consideration is to select an index that effectively measures drought duration. With West Nile virus, it is the post-drought dispersal of birds that influences human infection [80,81], so accurately assessing the lagged response means effectively capturing the time period of drought exposure. When considering the tradeoffs of choosing a drought index, one would give higher priority to capturing temporality, as opposed to characteristics like spatial extent or severity, that might be less important to dispersing birds.

Conversely, consider another vector-related outcome of drought and tick populations. Ticks are the known vectors for multiple human diseases, including Lyme disease, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, and others. Unlike mosquitoes, which benefit from drought conditions, dry conditions will negatively influence ticks. Tick ecology is driven by microclimates, including a preference for high relative humidity, drainage, and vegetation height [82,83] with poor survival under low humidity and high temperature conditions [47]. Increased desiccation from drought will directly harm tick populations [84]. Therefore, the ideal drought index for tick-borne disease would emphasize short-term drought conditions that focus on soil moisture, vegetation, or evaporative demand. The co-occurrence of rapid drought with heat waves (e.g. flash droughts) might also be a strong consideration.

While acknowledging that the type of drought impacting ticks would likely be quite different from conditions impacting mosquitoes, it is not clear how the authors selected their drought measures in published West Nile Virus and tick studies. Shaman et al (2002) and Paull et al (2017) both utilized the Palmer Drought Severity Index, while Johnson and Sukhdeo (2013) incorporated weather station data and compared this to long-term trends. The studies did not discuss alternate drought exposure metrics or different drought definitions in their evaluations. It has been found that inconsistent exposure definitions for other environmental hazards, such as heatwaves, may substantially influence health effects estimation and hinder the development of early warning systems [85,56]. Failure to properly consider the drought definition may result in incorrect health effect estimates or at worst a false association with disease. But how to identify the ‘best’ drought definition is an active and complex question. Cycling through different drought definitions using the over one hundred existing drought indices and testing their association with multiple health outcomes would be impractical, yet no alternative solution has been apparent. Identifying the most accessible, globally reproducible, and public health appropriate drought indices should be a priority of future work.

Knowing the at-risk Populations

Drought events are geographically large and impact broad populations, but the vulnerability of those affected varies substantially by subgroup. Sociodemographic and occupational factors are especially critical for community susceptibility and resilience. Populations reliant on agriculture for livelihoods or sustenance are vulnerable to food insecurity, malnutrition, and the accompanying psychosocial stress when drought causes economic loss [86,87]. Those in farming occupations already have higher rates of suicide and the impacts from drought have been shown to increase their mental health threats [40,88]. In general, rural individuals show greater mental health related stress from drought events compared to urban counterparts with this divide increasing for populations that are already disadvantaged, including remote, aboriginal, and indigenous communities [89–91]. However, urban communities may experience their own crises and disparities resulting from drought. From 2015 to 2018, the City of Cape Town, South Africa experienced an extended drought and increasingly dire water shortage that included the threat of ‘Day Zero,’ a period when water reservoirs would be completely exhausted [92]. While Day Zero was avoided, the city’s household water restrictions and rationing disproportionately harmed its most disadvantaged residents. In Cape Town, predominantly black and lower-income households often reside in multifamily or extended homes. These larger households with more individuals per property experienced greater hardship to reduce water consumption, as all individuals have basic water needs [93]. In wealthier households, a smaller number of people and the prevalence of water-reliant luxuries, such as landscaping or pools, often meant that water cuts could be instituted with relatively little impact on individual water demands [93].

Among age-groups, children and elderly are both vulnerable to various drought-related health outcomes, such as respiratory and waterborne diseases [61,63,65,94,95], while youths and working age adults are vulnerable to mental health effects from drought [91,39,42]. These studies hypothesize that older adults may better cope with the psychosocial stress of natural disasters having experienced them before [39]. Reliance on small or inadequately maintained water systems puts populations at risk for drinking water contamination during drought or limited water resources for hygiene and food washing [94,96]. Lastly, lowered surface water volumes put recreational water users at risk of waterborne disease and injury from aquatic accidents [86].

Following a natural disaster, the displacement of populations presents a challenge for both identifying vulnerable groups, evaluating overall health effects, and reducing disparities [7]. For some disasters, such as hurricanes, people that are displaced or temporarily housed are tracked by government agencies, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency in the United States. Researchers can partner with these groups and identify affected individuals to evaluate their health burdens resulting from natural disasters. But, as a slow-moving environmental hazard, drought rarely result in rapid and federally supported relocations. As families trickle away from stricken areas, it becomes difficult to follow-up on the health impacts from drought, adding potential misclassification to health effects evaluation [97].

Is it Drought Alone? Or Exacerbation of Other Extreme Events?

Estimating the health effects of drought is complex because drought exposures rarely occur in isolation. Droughts are part of interrelated environmental phenomenon that may trigger or exacerbate the occurrences of multiple extreme weather events, such as dust storms, wildfires, or heatwaves [30,97]. To accurately evaluate the impacts of drought, investigators must consider if the drought should be investigated alone or jointly with other simultaneous exposures, a phenomenon known as compound risks [54,98,99]. For example, it is known that dry soil produces less evaporative cooling, which makes surface temperatures hotter during dry periods [100]. Therefore, the probability and severity of a heatwave increases during drought compared to non-drought conditions [101,102] and the simultaneous occurrence of drought and heatwaves is called a ‘flash drought’ [103,104]. Heat waves have killed at least 4,275 people during the 30 droughts that have been designated as billion dollar disasters since 1980 [105]. While many heatwave and health investigations have investigated how exposure definitions and geographic variability in trends influence effect estimates [56,85,106], few have examined whether estimated heatwave health risks are mediated by drought conditions.

Drought conditions have also been associated with worsening air quality attributable to more frequent or severe emissions from wildfires and dust storms [15,28] and can exacerbate air pollution disparities [69,107]. Drought will intensify wildfire seasons by increasing the availability of fuel and decreasing surface soil moisture [34]. Models predict that by 2050 increasing temperature and drought from climate change will double wildfire related aerosols and increase overall carbon aerosols by 40% in the western United States [108]. Fine dust concentrations will similarly increase during drought conditions and are estimated to increase premature mortality by 24% and 130% under increasingly severe climate change scenarios [28]. Air quality issues from wildfires and dust storms are known to transfer across large distances and impact populations far from a source location.

Contrary to what is expected, droughts produce conditions that can lead to flooding. Decreased soil moisture and changes to the landscape during drought cause a reduction in precipitation soil absorption capacity and lead to flash flood conditions. In addition to impacting physical hazards, the occurrence of a drought is likely to increase stress on both individuals and communities. If a drought is high severity or persists for extended periods of time, the continued exposure will likely lower the populations baseline susceptibility to other extreme events. If a flood, wildfire, or other natural disaster event takes place following a drought, the community may be at greater vulnerability to this second exposure, particularly if there is inadequate time to regain their resilience [109]. Future research should consider the synergy between drought and other extreme weather events and identify whether the risks from natural disasters are modified during drought conditions. This has important consequences from a health preparedness standpoint. Risk mitigation should consider not just an emergency response to drought, but a response to the increased likelihood of related natural disasters. Since drought is slow to develop, comprehensive risk strategies can be instituted prior to a drought reaching a severe point and proactively protect against these multiple effects.

4. Conclusions

Droughts are a constant threat to the United States and other parts of the world. While the impacts of drought are sometimes less apparent, their consequences can be as severe and long-lasting as any other disaster. Over the last forty years, droughts are the third costliest weather-related disaster in the United States in dollars and the second costliest in human lives [105]. However, droughts do not garner as much attention from the public health, healthcare, and emergency preparedness sectors. Most of the time droughts are perceived as threats to agriculture and water resources, but not threats to our communities or health. For sectors that work on health security to perceive drought as a public health concern, the scientific community must first identify the health issues that are connected to drought and the populations that are more susceptible. Determining these relationships will help with mitigation efforts necessary for reducing the health risks that occur during droughts. Because droughts are likely to continue to increase in intensity and frequency in the future with anthropogenic climate change, it is crucial that the relationships between drought and health are better understood today before the risks increase in magnitude.

Evaluation of multiple drought definitions will help drought early warning systems capture health risks and applying this information to seasonal drought forecasts can provide time for health professionals to prepare for upcoming health threats. As mentioned above, no current definition of drought or individual drought index is designed to capture health effects. Because of the variety of health impacts that can manifest from drought events, a single drought index is unlikely to capture the complexity of all possible health outcomes. Utilizing best practices for selecting drought indices enables a better evaluation of health threats and allows us to use already operational products, thus eliminating the need to create another drought index to populate the list of numerous existing metrics. Instead, careful consideration is warranted to identify the appropriate drought metric and understanding the environmental triggers leading to a health threat will assist in selecting the appropriate drought measure. Matching drought indices with health outcomes will provide more accurate and reliable early warnings. In the prescribed methods listed in this paper, there is an opportunity to acknowledge the health threats from droughts, better evaluate them, and reduce the negative health outcomes through more informed mitigation strategies.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Integrated Drought Information System (grant NA20 OAR4310368), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (grant U54 OH007548-15) awarded to the Great Plains Center for Agricultural Health, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (ROSES grant 8ONSSC22K1050). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC, NOAA, NASA, or the Great Plains Center for Agricultural Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no actual or competing financial interests

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors Jesse Berman, Azar Abadi, and Jesse Bell declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

5. References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* Of importance,

** Of major importance

- 1.Reidmiller D, Avery C, Easterling D, Kunkel K, Lewis K, Maycock T, et al. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Global Change Research Program; 2018. p. 1515. Available from: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov [Google Scholar]

- 2.IPCC. Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023. [cited 2023 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson BG, Bell ML. Weather-Related Mortality. Epidemiology. 2009;20:205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz L, Hansen K, Alari A, Ilango SD, Bernal N, Basu R, et al. Spatial variation in the joint effect of extreme heat events and ozone on respiratory hospitalizations in California. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118:e2023078118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Y, Gasparrini A, Armstrong BG, Tawatsupa B, Tobias A, Lavigne E, et al. Heat Wave and Mortality: A Multicountry, Multicommunity Study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2017;125:087006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parks RM, Benavides J, Anderson GB, Nethery RC, Navas-Acien A, Dominici F, et al. Association of Tropical Cyclones With County-Level Mortality in the US. JAMA. 2022;327:946–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raker EJ, Arcaya MC, Lowe SR, Zacher M, Rhodes J, Waters MC. Mitigating Health Disparities After Natural Disasters: Lessons From The RISK Project. Health Affairs. 2020;39:2128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, Kiang MV, Rodriguez I, Fuller A, et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilera R, Corringham T, Gershunov A, Leibel S, Benmarhnia T. Fine Particles in Wildfire Smoke and Pediatric Respiratory Health in California. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020027128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid CE, Maestas MM. Wildfire smoke exposure under climate change: impact on respiratory health of affected communities. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019;25:179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fann N, Alman B, Broome RA, Morgan GG, Johnston FH, Pouliot G, et al. The health impacts and economic value of wildland fire episodes in the U.S.: 2008–2012. Science of The Total Environment. 2018;610–611:802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterson DL, Wright H, Harris PNA. Health Risks of Flood Disasters. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;67:1450–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations. Land and Drought | UNCCD [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 6]. Available from: http://www2.unccd.int/issues/land-and-drought

- 14.Luber G, Lemery J. Global Climate Change and Human Health: From Science to Practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanke C, Kerac M, Prudhomme C, Medlock J, Murray V. Health Effects of Drought: a Systematic Review of the Evidence. PLoS Currents. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Drought | Land & Water [Internet]. Drought. 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 3]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/land-water/water/drought/en/

- 17.United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. The Drought Initiative [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.unccd.int/land-and-life/drought/drought-initiative

- 18.Rippey BR. The U.S. drought of 2012. Weather and Climate Extremes. 2015;10:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook BI, Smerdon JE, Seager R, Cook ER. Pan-Continental Droughts in North America over the Last Millennium. J Climate. 2013;27:383–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin D, Anchukaitis KJ. How unusual is the 2012–2014 California drought? Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41:2014GL062433. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geirinhas JL, Russo AC, Libonati R, Miralles DG, Ramos AM, Gimeno L, et al. Combined large-scale tropical and subtropical forcing on the severe 2019–2022 drought in South America. npj Clim Atmos Sci. 2023;6:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moravec V, Markonis Y, Rakovec O, Svoboda M, Trnka M, Kumar R, et al. Europe under multi-year droughts: how severe was the 2014–2018 drought period? Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:034062. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Meteorological Society. Meteorological drought-policy statement. 1997;78:847–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vins H, Bell J, Saha S, Hess JJ. The Mental Health Outcomes of Drought: A Systematic Review and Causal Process Diagram. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12:13251–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra AK, Singh VP. A review of drought concepts. Journal of Hydrology. 2010;391:202–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Below R, Grover-Kopec E, Dilley M. Documenting Drought-Related Disasters A Global Reassessment. The Journal of Environment Development. 2007;16:328–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Li W. Drought Impacts on PM2.5 Composition and Amount Over the US During 1988–2018. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 2022;127:e2022JD037677. * • An examination of direct impacts of drought on fine particulate matter and the components of PM2.5, which have implications for relationships with health

- 28.Achakulwisut P, Mickley LJ, Anenberg SC. Drought-sensitivity of fine dust in the US Southwest: Implications for air quality and public health under future climate change. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13:054025. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Xie Y, Dong W, Ming Y, Wang J, Shen L. Adverse effects of increasing drought on air quality via natural processes. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2017;17:12827–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Libonati R, Geirinhas JL, Silva PS, Monteiro dos Santos D, Rodrigues JA, Russo A, et al. Drought–heatwave nexus in Brazil and related impacts on health and fires: A comprehensive review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2022;1517:44–62. ** • An important review of compound environmental exposures between drought, heat, and wildfires in South America, and their increased impact on health

- 31. Sutanto SJ, Vitolo C, Di Napoli C, D’Andrea M, Van Lanen HAJ. Heatwaves, droughts, and fires: Exploring compound and cascading dry hazards at the pan-European scale. Environment International. 2020;134:105276. ** • An important investigation of compound and cascading environmental exposures between drought, heat, and wildfires in Europe, and their increased impact on health and geographic areas of high concern

- 32.Bell JE, Brown CL, Conlon K, Herring S, Kunkel KE, Lawrimore J, et al. Changes in extreme events and the potential impacts on human health. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 2017;0:null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadley MB, Henderson SB, Brauer M, Vedanthan R. Protecting Cardiovascular Health From Wildfire Smoke. Circulation. 2022;146:788–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruffault J, Curt T, Martin-StPaul NK, Moron V, Trigo RM. Extreme wildfire events are linked to global-change-type droughts in the northern Mediterranean. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 2018;18:847–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Littell JS, Peterson DL, Riley KL, Liu Y, Luce CH. A review of the relationships between drought and forest fire in the United States. Global Change Biology. 2016;22:2353–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiavoni G, D’Amato G, Afferni C. The dangerous liaison between pollens and pollution in respiratory allergy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2017;118:269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung S, Estrella N, Pfaffl MW, Hartmann S, Ewald F, Menzel A. Impact of elevated air temperature and drought on pollen characteristics of major agricultural grass species. PLOS ONE. 2021;16:e0248759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albrecht G, Sartore G-M, Connor L, Higginbotham N, Freeman S, Kelly B, et al. Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15:S95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanigan IC, Schirmer J, Niyonsenga T. Drought and Distress in Southeastern Australia. EcoHealth. 2018;15:642–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berman JD, Ramirez MR, Bell JE, Bilotta R, Gerr F, Fethke NB. The association between drought conditions and increased occupational psychosocial stress among U.S. farmers: An occupational cohort study. Science of The Total Environment. 2021;798:149245. * • A unique U.S. study that evaluates drought risk for an occupational subgroup (e.g. farmers) and occupational stress related to drought exposure

- 41.Varshney K, Makleff S, Krishna RN, Romero L, Willems J, Wickes R, et al. Mental health of vulnerable groups experiencing a drought or bushfire: A systematic review. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. 2023;10:e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanigan IC, Butler CD, Kokic PN, Hutchinson MF. Suicide and drought in New South Wales, Australia, 1970–2007. PNAS. 2012;109:13950–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viswanathan DJ, Veerakumar AM, Kumarasamy H. Depression, Suicidal Ideation, and Resilience among Rural Farmers in a Drought-Affected Area of Trichy District, Tamil Nadu. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2019;10:238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y, Wheeler SA, Zuo A. Drought and hotter temperature impacts on suicide: evidence from the Murray–Darling basin, Australia. Climate Change Economics. 2023;2350024. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hanigan IC, Chaston TB. Climate Change, Drought and Rural Suicide in New South Wales, Australia: Future Impact Scenario Projections to 2099. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19:7855. * • An estimated projection of future climate impacts on drought in Australia and the impacts on suicide with young rural populations identified at greatest risk

- 46.Petkova EP, Celovsky AS, Tsai W-Y, Eisenman DP. Mental Health Impacts of Droughts: Lessons for the U.S. from Australia. In: Leal Filho W, Keenan JM, editors. Climate Change Adaptation in North America: Fostering Resilience and the Regional Capacity to Adapt. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Couper LI, MacDonald AJ, Mordecai EA. Impact of prior and projected climate change on US Lyme disease incidence. Global Change Biology. 2021;27:738–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charnley GEC, Kelman I, Murray KA. Drought-related cholera outbreaks in Africa and the implications for climate change: a narrative review. Pathogens and Global Health. 2022;116:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Froelich B, Gonzalez R, Blackwood D, Lauer K, Noble R. Decadal monitoring reveals an increase in Vibrio spp. concentrations in the Neuse River Estuary, North Carolina, USA. PLOS ONE. 2019;14:e0215254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Head JR, Sondermeyer-Cooksey G, Heaney AK, Yu AT, Jones I, Bhattachan A, et al. Effects of precipitation, heat, and drought on incidence and expansion of coccidioidomycosis in western USA: a longitudinal surveillance study. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2022;6:e793–803. * • An analysis of drought impacts on the transmission of coccidioidomycosis in the western U.S

- 51.Tong DQ, Wang JXL, Gill TE, Lei H, Wang B. Intensified dust storm activity and Valley fever infection in the southwestern United States. Geophys Res Lett. 2017;44:2017GL073524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balbus J Understanding drought’s impacts on human health. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2017;1:e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Salvador C, Nieto R, Vicente-Serrano SM, García-Herrera R, Gimeno L, Vicedo-Cabrera AM. Public Health Implications of Drought in a Climate Change Context: A Critical Review. Annu Rev Public Health. 2023;44:213–32. ** • A review of global drought impacts and mitigation strategies through the lens of climate change

- 54. Salvador C, Nieto R, Linares C, Díaz J, Gimeno L. Effects of Droughts on Health: Diagnosis, Repercussion, and Adaptation in Vulnerable Regions under Climate Change. Challenges for Future Research. Science of The Total Environment. 2020;703:134912. * • A perspective on drought and health research, future areas of priority, the complexity of performing drought and health research

- 55. Sugg M, Runkle J, Leeper R, Bagli H, Golden A, Handwerger LH, et al. A scoping review of drought impacts on health and society in North America. Climatic Change. 2020;162:1177–95. ** • A scoping review of drought impacts on health in North America with a lens on identifying research gaps and future priorities

- 56.Xu Z, FitzGerald G, Guo Y, Jalaludin B, Tong S. Impact of heatwave on mortality under different heatwave definitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International. 2016;89–90:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heim RR. A Review of Twentieth-Century Drought Indices Used in the United States. Bull Amer Meteor Soc. 2002;83:1149–65. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah D, Shah HL, Dave HM, Mishra V. Contrasting influence of human activities on agricultural and hydrological droughts in India. Science of The Total Environment. 2021;774:144959. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Zhang M, He X, Ren L, Pan M, Yu X, et al. Contrasting Influences of Human Activities on Hydrological Drought Regimes Over China Based on High-Resolution Simulations. Water Resources Research. 2020;56:e2019WR025843. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilhite DA, Glantz MH. Understanding: the Drought Phenomenon: The Role of Definitions. Water International. 1985;10:111–20. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berman JD, Ebisu K, Peng RD, Dominici F, Bell ML. Drought and the risk of hospital admissions and mortality in older adults in western USA from 2000 to 2013: a retrospective study. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2017;1:e17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salvador C, Nieto R, Linares C, Diaz J, Gimeno L. Effects on daily mortality of droughts in Galicia (NW Spain) from 1983 to 2013. Science of The Total Environment. 2019;662:121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang B, Wang S, Li L, Xu S, Li C, Li S, et al. The association between drought and outpatient visits for respiratory diseases in four northwest cities of China. Climatic Change. 2021;167:2. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lynch KM, Lyles RH, Waller LA, Abadi AM, Bell JE, Gribble MO. Drought severity and all-cause mortality rates among adults in the United States: 1968–2014. Environmental Health. 2020;19:52. * • A national U.S. study that evaluated associations between mortality and drought exposure for different age, sex, and race subgroups

- 65.Abadi AM, Gwon Y, Gribble MO, Berman JD, Bilotta R, Hobbins M, et al. Drought and all-cause mortality in Nebraska from 1980 to 2014: Time-series analyses by age, sex, race, urbanicity and drought severity. Science of The Total Environment. 2022;840:156660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salvador C, Nieto R, Linares C, Díaz J, Alves CA, Gimeno L. Drought effects on specific-cause mortality in Lisbon from 1983 to 2016: Risks assessment by gender and age groups. Science of The Total Environment. 2021;751:142332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dai A Characteristics and trends in various forms of the Palmer Drought Severity Index during 1900–2008. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres [Internet]. 2011. [cited 2019 Oct 23];116. Available from: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2010JD015541 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morgenstern H, Thomas D. Principles of study design in environmental epidemiology. 1993;101:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee HJ, Bell ML, Koutrakis P. Drought and ozone air quality in California: Identifying susceptible regions in the preparedness of future drought. Environmental Research. 2023;216:114461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vicente-Serrano SM, Beguería S, López-Moreno JI. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J Climate. 2010;23:1696–718. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beguería S, Vicente-Serrano SM. SPEI: Calculation of the Standardised Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=SPEI

- 72.Dracup JA, Lee KS, Paulson EG. On the definition of droughts. Water Resources Research. 1980;16:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 73.McEvoy DJ, Huntington JL, Hobbins MT, Wood A, Morton C, Anderson M, et al. The Evaporative Demand Drought Index. Part II: CONUS-Wide Assessment against Common Drought Indicators. Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2016;17:1763–79. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bell JE, Herring SC, Jantarasami L, Adrianopoli C, Benedict K, Conlon K, et al. Ch. 4: Impacts of Extreme Events on Human Health [Internet]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC; 2016. Apr p. 99–128. Available from: /extreme-events [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith KH, Tyre AJ, Hamik J, Hayes MJ, Zhou Y, Dai L. Using Climate to Explain and Predict West Nile Virus Risk in Nebraska. GeoHealth. 2020;4:e2020GH000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paull SH, Horton DE, Ashfaq M, Rastogi D, Kramer LD, Diffenbaugh NS, et al. Drought and immunity determine the intensity of West Nile virus epidemics and climate change impacts. Proc Biol Sci. 2017;284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaman J, Day JF, Stieglitz M. Drought-Induced Amplification of Saint Louis encephalitis virus, Florida. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:575–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hagan RW, Didion EM, Rosselot AE, Holmes CJ, Siler SC, Rosendale AJ, et al. Dehydration prompts increased activity and blood feeding by mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson BJ, Sukhdeo MVK. Drought-Induced Amplification of Local and Regional West Nile Virus Infection Rates in New Jersey. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heidecke J, Schettini AL, Rocklöv J. West Nile virus eco-epidemiology and climate change. PLOS Climate. 2023;2:e0000129. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watts MJ, Sarto i Monteys V, Mortyn PG, Kotsila P. The rise of West Nile Virus in Southern and Southeastern Europe: A spatial–temporal analysis investigating the combined effects of climate, land use and economic changes. One Health. 2021;13:100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Janzén T, Hammer M, Petersson M, Dinnétz P. Factors responsible for Ixodes ricinus presence and abundance across a natural-urban gradient. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0285841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Medlock JM, Vaux AGC, Hansford KM, Pietzsch ME, Gillingham EL. Ticks in the ecotone: the impact of agri-environment field margins on the presence and intensity of Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in farmland in southern England. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2020;34:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown L, Medlock J, Murray V. Impact of drought on vector-borne diseases – how does one manage the risk? Public Health. 2014;128:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heo S, Bell ML, Lee J-T. Comparison of health risks by heat wave definition: Applicability of wet-bulb globe temperature for heat wave criteria. Environmental Research. 2019;168:158–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.CDC, EPA, NOAA, AWWA. When Every Drop Counts: Protecting Public Health During Drought Conditions—A Guide for Public Health Professionals [Internet]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/Docs/When_Every_Drop_Counts.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 87.Friel S, Berry H, Dinh H, O’Brien L, Walls HL. The impact of drought on the association between food security and mental health in a nationally representative Australian sample. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peterson C, Stone DM, Marsh SM, Schumacher PK, Tiesman HM, McIntosh WL, et al. Suicide Rates by Major Occupational Group — 17 States, 2012 and 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.OBrien LV, Berry HL, Coleman C, Hanigan IC. Drought as a mental health exposure. Environmental Research. 2014;131:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rigby CW, Rosen A, Berry HL, Hart CR. If the land’s sick, we’re sick:* The impact of prolonged drought on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2011;19:249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Austin EK, Handley T, Kiem AS, Rich JL, Lewin TJ, Askland HH, et al. Drought-related stress among farmers: findings from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study. Medical Journal of Australia. 2018;209:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Millington N, Scheba S. Day Zero and The Infrastructures of Climate Change: Water Governance, Inequality, and Infrastructural Politics in Cape Town’s Water Crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2021;45:116–32. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Enqvist JP, Ziervogel G. Water governance and justice in Cape Town: An overview. WIREs Water. 2019;6:e1354. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yusa A, Berry P, J. Cheng J, Ogden N, Bonsal B, Stewart R, et al. Climate Change, Drought and Human Health in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12:8359–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gwon Y, Ji Y, Bell JE, Abadi AM, Berman JD, Rau A, et al. The Association between Drought Exposure and Respiratory-Related Mortality in the United States from 2000 to 2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20:6076. * • A U.S. based study identifying geographic and individual risk differences in drought associated respiratory disease

- 96.Sena A, Barcellos C, Freitas C, Corvalan C. Managing the Health Impacts of Drought in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11:10737–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.LaKind JS, Overpeck J, Breysse PN, Backer L, Richardson SD, Sobus J, et al. Exposure science in an age of rapidly changing climate: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2016;26:jes201635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pescaroli G, Alexander D. Understanding Compound, Interconnected, Interacting, and Cascading Risks: A Holistic Framework. Risk Analysis. 2018;38:2245–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.AghaKouchak A, Cheng L, Mazdiyasni O, Farahmand A. Global warming and changes in risk of concurrent climate extremes: Insights from the 2014 California drought. Geophysical Research Letters. 2015;8847–52. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yin D, Roderick ML, Leech G, Sun F, Huang Y. The contribution of reduction in evaporative cooling to higher surface air temperatures during drought. Geophysical Research Letters. 2014;41:7891–7. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Black E, Blackburn M, Harrison G, Hoskins B, Methven J. Factors contributing to the summer 2003 European heatwave. Weather. 2004;59:217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peterson TC, Heim RR, Hirsch R, Kaiser DP, Brooks H, Diffenbaugh NS, et al. Monitoring and Understanding Changes in Heat Waves, Cold Waves, Floods, and Droughts in the United States: State of Knowledge. Bull Amer Meteor Soc. 2013;94:821–34. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang L, Yuan X, Xie Z, Wu P, Li Y. Increasing flash droughts over China during the recent global warming hiatus. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:30571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Otkin JA, Svoboda M, Hunt ED, Ford TW, Anderson MC, Hain C, et al. Flash Droughts: A Review and Assessment of the Challenges Imposed by Rapid-Onset Droughts in the United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2018;99:911–9. [Google Scholar]

- 105.NOAA NCEI. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2020 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/

- 106.Chen K, Bi J, Chen J, Chen X, Huang L, Zhou L. Influence of heat wave definitions to the added effect of heat waves on daily mortality in Nanjing, China. Science of The Total Environment. 2015;506–507:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zeighami A, Kern J, Yates AJ, Weber P, Bruno AA. U.S. West Coast droughts and heat waves exacerbate pollution inequality and can evade emission control policies. Nat Commun. 2023;14:1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Spracklen DV, Mickley LJ, Logan JA, Hudman RC, Yevich R, Flannigan MD, et al. Impacts of climate change from 2000 to 2050 on wildfire activity and carbonaceous aerosol concentrations in the western United States. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres [Internet]. 2009. [cited 2019 Jun 9];114. Available from: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008JD010966 [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ebi KL, Bowen K. Extreme events as sources of health vulnerability: Drought as an example. Weather and Climate Extremes. 2016;11:95–102. [Google Scholar]