Abstract

Background

In addition to their proliferative and differentiating effects, several growth factors are capable of inducing a sustained airway smooth muscle (ASM) contraction. These contractile effects were previously found to be dependent on Rho-kinase and have also been associated with the production of eicosanoids. However, the precise mechanisms underlying growth factor-induced contraction are still unknown. In this study we investigated the role of contractile prostaglandins and Rho-kinase in growth factor-induced ASM contraction.

Methods

Growth factor-induced contractions of guinea pig open-ring tracheal preparations were studied by isometric tension measurements. The contribution of Rho-kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and cyclooxygenase (COX) to these reponses was established, using the inhibitors Y-27632 (1 μM), U-0126 (3 μM) and indomethacin (3 μM), respectively. The Rho-kinase dependency of contractions induced by exogenously applied prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was also studied. In addition, the effects of the selective FP-receptor antagonist AL-8810 (10 μM) and the selective EP1-antagonist AH-6809 (10 μM) on growth factor-induced contractions were investigated, both in intact and epithelium-denuded preparations. Growth factor-induced PGF2α-and PGE2-release in the absence and presence of Y-27632, U-0126 and indomethacin, was assessed by an ELISA-assay.

Results

Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced contractions of guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle preparations were dependent on Rho-kinase, MAPK and COX. Interestingly, growth factor-induced PGF2α-and PGE2-release from tracheal rings was significantly reduced by U-0126 and indomethacin, but not by Y-27632. Also, PGF2α-and PGE2-induced ASM contractions were largely dependent on Rho-kinase, in contrast to other contractile agonists like histamine. The FP-receptor antagonist AL-8810 (10 μM) significantly reduced (approximately 50 %) and the EP1-antagonist AH-6809 (10 μM) abrogated growth factor-induced contractions, similarly in intact and epithelium-denuded preparations.

Conclusion

The results indicate that growth factors induce ASM contraction through contractile prostaglandins – not derived from the epithelium – which in turn rely on Rho-kinase for their contractile effects.

Background

Growth factors have been reported to be involved in proliferation and differentiation of smooth muscle cells from a variety of tissues, including vasculature and airways [1,2]. In addition, several growth factors have been shown to induce contraction of vascular smooth muscle [3,4]. The mechanisms by which growth factors induce contraction have only been partly elucidated. Recent evidence has indicated that growth factor-receptors, such as the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-receptor, can activate the Rho/Rho-kinase pathway directly [5] and may be involved in smooth muscle contraction via Rho-kinase [6]. Smooth muscle contraction is mainly regulated by the phosphorylation level of the 20 kDa regulatory myosin light chain (MLC) [7]. MLC phosphorylation can be initiated by an increase in intracellular Ca2+-concentration ([Ca2+]i) followed by the Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). The extent of MLC phosphorylation is determined by the ratio of MLCK (MLC-phosphorylation) to myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP)(MLC-dephosphorylation) activities [8]. Activated Rho-kinase mainly exerts its effect through inhibition of MLCP, resulting in an enhanced MLC phosphorylation and thus an increased level of contraction at a fixed [Ca2+]i (Ca2+-sensitization) [6,9].

In bovine airway smooth muscle, it has been demonstrated that prolonged incubation with growth factors modulates the phenotypic state of the muscle [10,11]. They have also been described to exert acute contractile effects on guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle [12,13]. Recently, we showed that growth factors are also capable of inducing human bronchial smooth muscle contraction. Thus, angiotensin II as well as IGF-1 induced a sustained contraction, which was completely dependent on Rho-kinase [14].

These observations may be of pathophysiological and pharmacotherapeutical interest, as expression levels both of growth factors (EGF)[15] and of receptors of growth factors (EGF[15], PDGF[15,16]) have been found elevated in asthmatic airways. Also, increased levels of PDGF have been found in exhaled breath condensate of asthmatic children with severe airflow limitation [17]. Moreover, previous studies showed an augmented role of Rho-kinase in acetylcholine induced bronchial smooth muscle contraction after repeated allergen challenge in rats [18,19]. Furthermore, we have recently demonstrated that the process of active allergic sensitization by itself, without subsequent allergen exposure, is sufficient to induce an enhanced role of Rho-kinase in guinea pig airway smooth muscle contraction ex vivo and airway resistance in vivo [20]. Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms by which growth factors induce a Rho-kinase dependent contraction is of pathophysiological and pharmacotherapeutical interest.

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) causes contraction of guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle via arachidonic acid metabolism in which presumably a tyrosine kinase and phospholipase A2 are involved [12,13]. It is well documented that receptor tyrosine kinases can activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-kinase (MEK)[21-23]. Activation of MAPK by MEK may result in the activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) [24] and subsequent production of arachidonic acid and prostaglandins. Several studies have demonstrated that contractile prostaglandins are dependent on Rho-kinase [20,25]. Altogether, it can be hypothesized that growth factor-induced contraction is mediated via the MEK-dependent, cPLA2-mediated production of prostaglandins and subsequent activation of Rho-kinase. Therefore, we investigated the effects of inhibition of Rho-kinase, MEK and cyclooxygenase (COX) on growth factor-induced prostaglandin-production and contraction, using guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle preparations. In addition, we investigated the effects of selective prostaglandin receptor antagonists on growth factor-induced contraction.

Methods

Animals

Outbred specified pathogen-free male Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs (Harlan, Heathfield, U.K.), weighing 500–700 g, were used in this study. All protocols described in this study were approved by the University of Groningen Committee for Animal Experimentation.

Isometric tension measurements

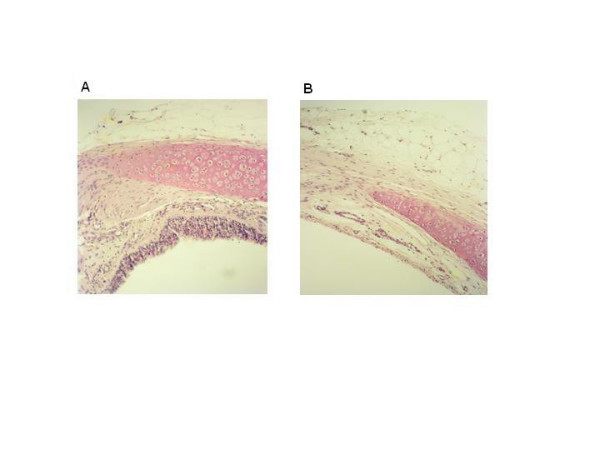

After experimental concussion and rapid exsanguination the trachea was removed and transferred to Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer solution (composition in mM: NaCl 117.5, KCl 5.6, MgSO4 1.18, CaCl2 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.28, NaHCO3 25.00 and D-glucose 5.55; pregassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH 7.4) at 37°C. The trachea was carefully prepared free of serosa and connective tissue. In some cases, the airway epithelium was carefully removed by moving a 15-cm woollen thread up and down the trachea twice. Epithelium denudation was confirmed by histological examination after fixating cryostat sections (5 μm) in acetone and staining with hematoxylin eosin. Single open-ring tracheal preparations were prepared and mounted for isometric recording, using Grass FT-03 transducers, in 20 ml water-jacketed organ baths (37°C) containing KH solution. During a 90 min equilibration period, with washouts every 30 min, resting tension was gradually adjusted to 0.5 g. Subsequently, the preparations were precontracted with 20 and 40 mM KCl. Following two wash-outs, maximal relaxation was established by the addition of 0.1 μM isoprenaline and tension was re-adjusted to 0.5 g, immediately followed by two changes of fresh KH-buffer. After another equilibration period of 30 min EGF (0.1, 1, 3, 10 or 30 ng/ml) or PDGF (0.1, 1, 3, 10 or 30 ng/ml) was applied or cumulative concentration response curves (CRCs) were constructed to stepwise increasing concentrations of histamine (1 nM – 100 μM), PGE2 (1 nM – 3μM) or PGF2α (1 nM – 10 μM). When maximal agonist-induced contraction was obtained, the tracheal rings were washed several times and maximal relaxation was established using isoprenaline. When used, the inhibitors of Rho-kinase (Y-27632, 1 μM), MAPK-ERK-kinase (MEK) (U-0126, 3 μM) or COX (indomethacin, 3 μM) were applied to the organ bath 30 min before agonist addition. This was also the case for the FP-receptor-and EP1-receptor-antagonists AL-8810 and AH-6809 (10 μM both, applied individually to separate preparations), respectively.

Measurement of prostaglandin F2α and prostaglandin E2 production

Guinea pig tracheal rings were incubated using a 24-wells plate at 37°C. Each well contained 1 ml KH-buffer and 7 tracheal rings. Twenty-one rings were isolated from every trachea, so three conditions per preparation could be tested. Following a 30 min pre-incubation period, 100 μl of the medium was taken as the first sample. Subsequently, PDGF (10 ng/ml) was applied. To determine the time dependency of prostaglandin (PG)-production, samples were collected at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30 min after PDGF-addition. Sampling was performed under a 95 % O2 / 5 % CO2 atmosphere. PGF2α-and PGE2-production was determined using an ELISA-assay according to the manufacturer's protocol (R&D Systems, U.K.).

Data analysis

All data represent means ± s.e. mean from n separate experiments. Statistical significance of differences was evaluated using either a one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-test or by a paired or unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test when appropriate, and significance was accepted when P<0.05.

Chemicals

Platelet-derived growth factor AB (PDGF-AB, human recombinant) was from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland) and epidermal growth factor (human recombinant), indomethacin, histamine dihydrochloride and (-)-isoprenaline hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). PGF2α was obtained from Pharmacia and Upjohn (Puurs, Belgium) and PGE2 was from BIOMOL (U.S.A). 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis [2-aminophenylthio]butadiene (U-0126), (+)-(R)-trans-4-(1-aminoethyl)-N-(4-pyridyl) cyclohexane carboxamide (Y-27632) and 6-isopropoxy-9-xanthone-2-carboxylic acid (AH-6809) were obtained from Tocris Cookson Ltd. (Bristol, U.K.). 9α, 15R-dihydroxy-1 1β-fluoro-15-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl)-16, 17, 18, 19, 20-pentanor-prosta-5Z, 13E-dien-1-oic acid (AL-8810) was obtained from Cayman Chemical (U.S.A). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Results

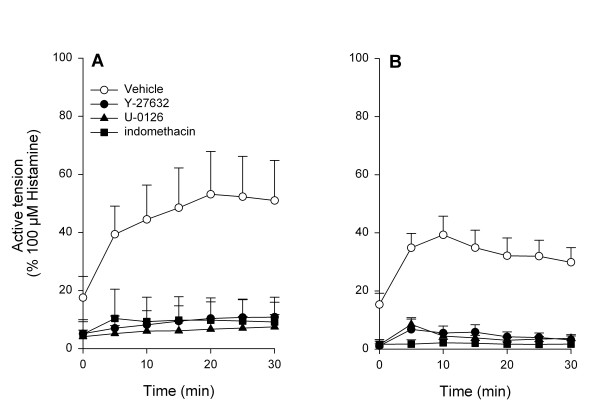

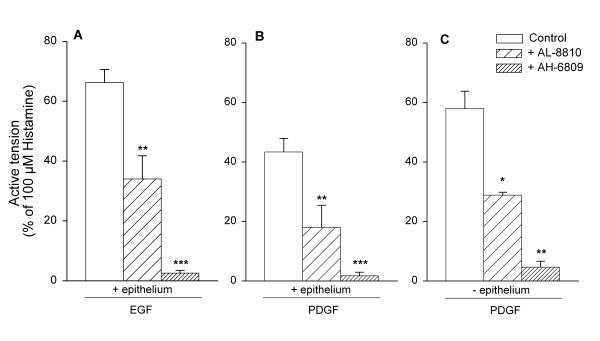

To investigate the contractile effects of EGF and PDGF on guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle, CRCs of the growth factors were constructed (Fig. 1). Both EGF and PDGF were capable of inducing concentration-dependent contractions, with a potency (EC50) of 6.7 ± 2.3 ng/ml for EGF and 6.4 ± 2.8 ng/ml for PDGF. As shown in Fig. 2, both growth factors induced a slowly developing sustained contraction, which was prevented almost completely in the presence of either Y-27632 (1 μM), U-0126 (3 μM) or indomethacin (3 μM). Also, basal myogenic tone (expressed with respect to maximal relaxation established with isoprenaline) was abolished by these inhibitors (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

EGF (A)-and PDGF (B)-induced contraction of guinea pig open-ring tracheal smooth muscle preparations. Responses shown are corrected for basal myogenic tone, which amounted to 0.21 ± 0.06 g on average (0 % growth factor effect). Maximal effects were reached at concentrations of 30 ng/ml and amounted 0.31 ± 0.04 g (EGF, 100 % effect) and 0.24 ± 0.06 g (PDGF, 100 % effect), corresponding to 19.8 ± 2.8 % and 15.3 ± 4.1 %, respectively, of maximal histamine-induced contraction. Data represent means ± s.e. mean of seven (EGF) or four (PDGF) experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Figure 2.

Effects of Y-27632 (1 μM), U-0126 (3 μM) and indomethacin (3 μM) on (A) EGF (10 ng/ml)-and (B) PDGF (10 ng/ml)-induced guinea pig trachealsmooth muscle contraction. Data represent means ± s.e. mean of five (EGF) or six (PDGF) experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Since both MEK-(U-0126) and COX-inhibition (indomethacin) prevented growth factor-induced contraction, we envisaged that growth factor-induced prostaglandin production would be responsible for the observed contractions.

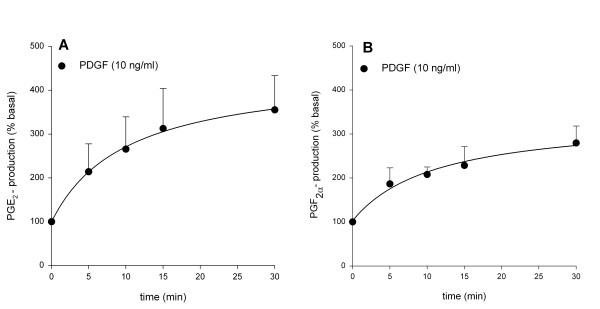

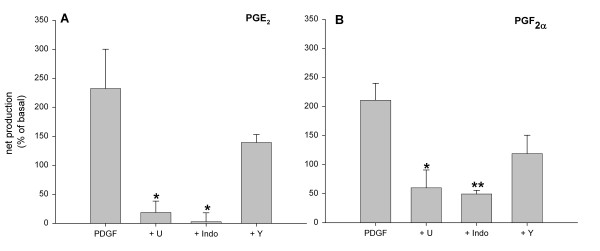

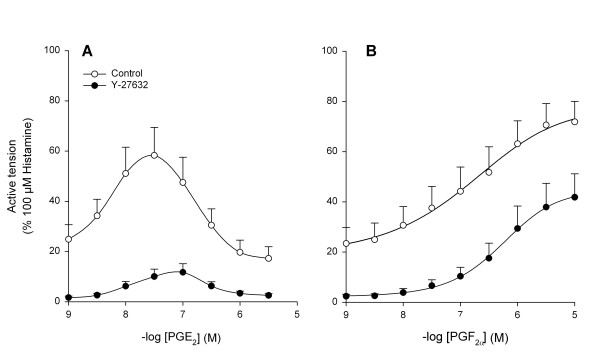

Stimulation of tracheal smooth muscle preparations with PDGF for 30 min greatly enhanced the release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by 255 ± 78 % (from 963 ± 245 to 2762 ± 138 pg/ml; p < 0.01 at t = 30 min; Fig. 3A) and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) by 182 ± 38 % (from 1093 ± 204 to 2929 ± 570 pg/ml; p < 0.05 at t = 30 min; Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 4, both the release of PGE2 and PGF2α were significantly reduced in the presence of U-0126 (3 μM) and indomethacin (3 μM). In contrast to growth factor-induced contraction, no significant effect of treatment with Y-27632 (1 μM) was found on PGE2 (p = 0.23) or PGF2α (p = 0.08) release. These findings would suggest that prostaglandins produced in response to growth factor stimulation are capable of inducing a Rho-kinase-dependent contraction. Application of PGE2 caused ASM contraction in concentrations up to 0.03 μM (pEC50 = 8.22 ± 0.07, Emax = 58.3 ± 11.2 %), but caused relaxation in higher concentrations (Fig. 5A). Indeed, Rho-kinase inhibition resulted in a decreased potency (pEC50 = 7.9 ± 0.2; p < 0.05) and maximal contraction (Emax = 11.7 ± 3.5 %; p < 0.05) of PGE2-induced contraction. PGF2α-induced contractions (pEC50 = 6.8 ± 0.2; Emax = 71.9 ± 8.2 %) were dependent on Rho-kinase as well, as indicated by the significantly decreased potency (pEC50 = 6.2 ± 0.2 ; p < 0.05) and maximal contraction (Emax = 41.8 ± 9.3 %; p < 0.05) after treatment with Y-27632 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 3.

Growth factor-induced PGE2 (A) and PGF2α (B) release from guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle preparations. Basal release amounted to 963 ± 245 pg/ml (PGE2) and 1093 ± 204 pg/ml (PGF2α). Data represent means ± s.e.mean of five experiments.

Figure 4.

Effects of U-0126 (3 μM), indomethacin (3 μM) and Y-27632 (1 μM) on growth factor-induced PGE2 (A) and PGF2α (B) release. Data represent means ± s.e.mean of six (PGE2) and five (PGF2α) experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to PDGF.

Figure 5.

Effects of Rho-kinase inhibition on prostaglandin-induced contraction. PGE2 (A)-and PGF2α (B)-induced contraction in the absence and presence of Y-27632 (1 μM) of guinea pig open-ring tracheal smooth muscle preparations. Data represent means ± s.e.mean of four (PGE2) and seven (PGF2α) experiments, each performed in duplicate.

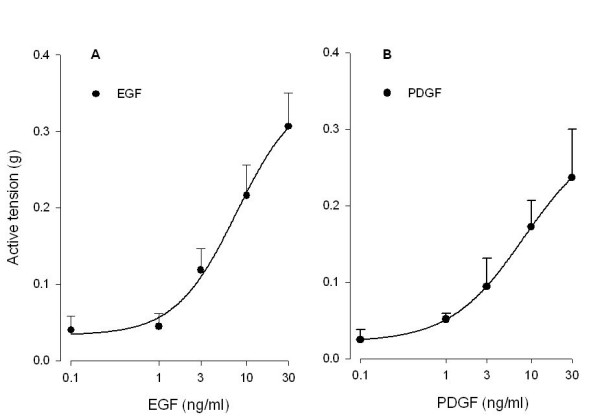

To establish the functional contribution of the contractile PGE2-sensitive EP1-receptor and the PGF2α-sensitive FP-receptor to growth factor-induced contraction, the selective EP1-receptor antagonist AH-6809 (10 μM) and the selective FP-receptor antagonist AL-8810 (10 μM) were used. Both EGF-and PDGF-induced contractions were significantly reduced after treatment with AL-8810 (46,7 ± 13.0 % and 52.7 ± 13.2 % inhibition, respectively; p < 0.01 both), whereas contractions were almost abolished after treatment with AH-6809 (95.1 ± 3.1 % and 94.4 ± 4.7 % inhibition, respectively; p < 0.001 both)(Fig. 6A,B). To determine whether the epithelium was the source of the prostaglandins involved in growth factor-induced contraction, the effects of AL-8810 and AH-6809 on epithelium-denuded tracheal preparations were studied. Complete denudation was achieved as illustrated in Fig. 7. In these preparations, PDGF induced a slightly higher contraction compared to that in intact preparations, however the difference was not significant. Similar to intact preparations, PDGF-induced contraction was significantly reduced by both AL-8810 (48.8 ± 7.1 % inhibition; p < 0.05; Fig. 6C) and AH-6809 (92.1 ± 3.0 % inhibition; p < 0.01); Fig. 6C). Moreover, the inhibition in denuded preparations was very similar to that in intact preparations, both for AL-8810 and AH-6809, indicating that FP-and EP1-receptor stimulation involved in growth factor-induced contraction occurs independently of epithelium.

Figure 6.

EGF (10 ng/ml, A)-and PDGF (10 ng/ml, B,C)-induced contraction of intact (A,B) and epithelium-denuded (C) guinea pig open-ring tracheal smooth muscle preparations in the absence or presence of AL-8810 (10 μM) or AH-6809 (10 μM). Data represent means ± s.e. mean of five (A,B) and three (C) experiments, each performed in duplicate. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to control.

Figure 7.

Representative photomicrograph of an intact (A) and epithelium-denuded (B) tracheal preparation. The photographs were taken at 100 × magnification.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that the growth factors EGF and PDGF induce contractions of guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle in a concentration dependent fashion. The concentration-effect range of EGF and PDGF (0.1 – 30 ng/ml) represents a pharmacological range very similar to other effects, such as mitogenesis of airway smooth muscle [26,10]. Since contractile effects of EGF have previously been associated with the production of eicosanoids [13] and contractions induced by of IGF-1 and angiotensin II appeared to be dependent on Rho-kinase [13,14], we analyzed whether contractions induced by submaximal concentrations of growth factors are dependent not only on Rho-kinase, but also on COX and MEK. This might be characteristic for growth factor-induced contraction, since potency and maximal contraction of histamine were shown to be independent of Rho-kinase, COX [20] and MEK (Schaafsma et al, unpublished observations) in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. Similarly, muscarinic receptor mediated contractions are only partially Rho-kinase-dependent [27,28], further illustrating the agonist-dependent role of Rho-kinase mediated calcium sensitization.

The role of Rho-kinase in growth factor-mediated effects could depend on the duration of growth factor stimulation. For instance, phenotypic modulation, as a consequence of 8 days stimulation with growth factors, or growth factor-induced proliferation of bovine tracheal smooth muscle, has been shown to be independent of Rho-kinase. However, in accordance with the effects of Rho-kinase inhibition on growth factor-induced contraction of human isolated bronchus [14], we demonstrate that Y-27632 fully inhibits growth factor-induced contraction of guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. This indicates that growth factor-induced acute (smooth muscle contraction) and long term (e.g. modulation of smooth muscle phenotype) effects in airway smooth muscle may be differentially dependent on Rho-kinase.

Since MEK and COX inhibition almost abrogated growth factor-induced contraction, it can be suggested that growth factor-induced contraction relies on the production of prostaglandins. In several studies, it has been demonstrated that cytosolic phospholipase A2 (PLA2) can be activated in response to growth factors in a MAPK-dependent fashion, which results in subsequent arachidonic acid production [29-31]. In addition, contractile activity of EGF in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle has been reported to be inhibited by indomethacin and by the phospholipase A2 inhibitor mepacrine [12]. As indicated by our results, PGF2α and PGE2 are being produced in response to PDGF-stimulation in a time-dependent fashion, similar to that of growth factor-induced contraction. Both prostaglandins are contractile agonists for airway smooth muscle [20,32,33]. Contractions induced by (exogenous) PGF2α and PGE2 were found to be largely dependent on Rho-kinase activity, which corresponds to observations in vascular smooth muscle [25,34], indicating that Rho-kinase plays an essential role in PGF2α-and PGE2-induced contractions. Interestingly, Rho-kinase inhibition had a more pronounced effect on PGE2-than on PGF2α-induced contractions. This can be explained, however, by realizing that the EP2-receptor mediated relaxation [35], as seen with the higher PGE2-concentrations, is suppressing the contractile phase more effectively when its Rho-kinase-dependent component is being inhibited.

In addition to direct contractile effects on guinea pig airway smooth muscle, PGF2α has been shown to augment cholinergic responsiveness of bovine airway smooth muscle [36], indicating an important role for PGF2α in regulating airway smooth muscle tone. PGF2α has been described to exert its contractile effects on smooth muscle through the FP-receptor [37,38]. Also, PGF2α-induced Ca2+-mobilization in vascular smooth muscle cells was dose-dependently inhibited by the selective FP-receptor antagonist AL-8810 [39]. In our study, a selective and effective concentration of AL-8810 [40,39] reduced EGF-and PDGF-induced contractions, indicating that PGF2α contributes to growth factor-induced contraction through the FP-receptor.

Smooth muscle contractions induced by PGE2 are predominantly mediated through activation of the EP1-receptor [41,32]. In guinea pig airway smooth muscle it has been previously found that PGE2-induced contractions could be dose-dependently inhibited by the EP1-receptor antagonist SC-19220 without modulating the relaxant activity (Van Amsterdam, 1991). Also, like PGF2α, PGE2 enhances cholinergic airway responsiveness of bovine airway smooth muscle [36]. In the present study we found that growth factor-induced contraction of guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle is essentially dependent on EP1-receptor stimulation, since the selective EP1-receptor antagonist AH-6809 [36] abrogated growth factor-induced contractions. Interestingly, these contractions were partially inhibited by FP-receptor blockade as well. From these observations, it may be hypothesized that PGF2α-mediated contractions partially rely on EP1-receptor stimulation (possibly by releasing small amounts of PGE2, selectively activating EP1-receptors) and that synergistic contractile effects of concomitant EP1-and FP-receptor stimulation occur.

Several growth factors, including EGF and PDGF, have been implicated in airway inflammation as they can be released from inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and eosinophils. Moreover, they can be derived from extravasated plasma, epithelial cells and the airway smooth muscle itself [2,42]. Growth factors are involved in tissue repair processes, therefore growth factor-induced contraction could protect damaged areas in the airways from the environment during these processes. In the pathophysiology of asthma, the repair process is usually not restricted to a single segment of the airways and growth factors may then contribute to airflow obstruction. Inhibition of such contractions might therefore be relevant under such pathophysiological conditions.

Conclusion

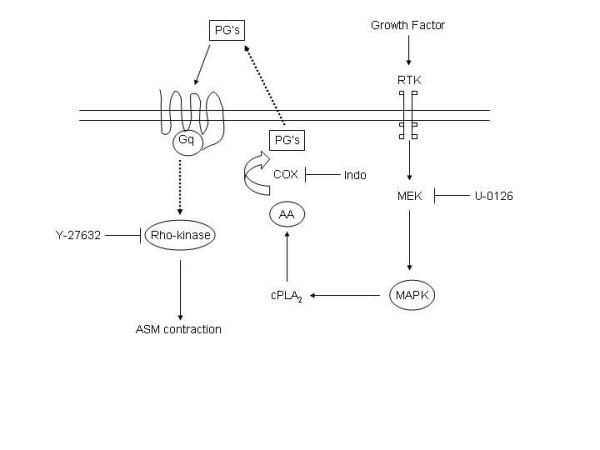

Our overall results indicate that EGF and PDGF induce airway smooth muscle contraction through contractile prostaglandins. These prostaglandins are presumably produced by the consecutive actions of MEK, cytosolic PLA2 and COX and in turn are dependent on Rho-kinase for their contractile effects (Fig. 8). Since growth factor-induced contractions were inhibited by antagonists of contractile prostaglandin receptors both in intact and epithelium-denuded preparations, it can be concluded that the prostaglandins involved in growth factor-induced contraction are not primarily derived from the epithelium. Since both growth factors and increased Rho-kinase activity are associated with pathophysiological conditions and growth factor-induced contraction is fully Rho-kinase dependent, inhibition of Rho-kinase might be of therapeutical interest in the treatment of inflammatory (airway) diseases.

Figure 8.

Putative mechanism of growth factor-induced airway smooth muscle contraction. Growth factors, like EGF and PDGF, bind to their receptors with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity (RTK) and activate MAPK, which may result in increased levels of arachidonic acid (AA) via cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) activation. As a consequence of cyclooxygenase (COX)-mediated conversion of AA, prostaglandins (PGs) are produced. These (contractile) prostaglandins, like PGF2α and PGE2, may in turn couple to their receptors and induce an airway smooth muscle contraction which is largely dependent on Rho-kinase. U-0126, indomethacin (indo) and Y-27632 are inhibitors of MAPK, COX and Rho-kinase, respectively.

Abbreviations

AA, arachidonic acid; AHR, airway hyperresponsiveness; ASM, airway smooth muscle; COX, cyclooxygenase; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; CRC, cumulative concentration response curve; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EP1-receptor, prostaglandin E2-receptor type 1; FP-receptor, prostaglandin F2α-receptor; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; Indo, indomethacin; KH, Krebs-Henseleit; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase-kinase (MEK); pEC50, -log10 of the concentration causing 50 % of the effect; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PG, prostaglandin; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGF2α, prostaglandin F2α; RTK, receptors with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DS designed and coordinated the study, performed a major part of the experiments, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. RG participated in the design of the study, assisted in performing part of the experiments and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. ISTB substantially assisted in performing the experiments. HM participated in the design of the study and the interpretation of the results. JZ participated in the design of the study, interpretation of results and final revision of the manuscript. SAN supervised the study, participated in its design and in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank the Netherlands Asthma Foundation for financial support (grant 01.83).

Contributor Information

Dedmer Schaafsma, Email: d.schaafsma@rug.nl.

Reinoud Gosens, Email: r.gosens@rug.nl.

I Sophie T Bos, Email: i.s.t.bos@rug.nl.

Herman Meurs, Email: h.meurs@rug.nl.

Johan Zaagsma, Email: j.zaagsma@rug.nl.

S Adriaan Nelemans, Email: s.a.nelemans@rug.nl.

References

- Bayes-Genis A, Conover CA, Schwartz RS. The insulin-like growth factor axis: A review of atherosclerosis and restenosis. Circ Res. 2000;86:125–130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst SJ. Airway smooth muscle as a target in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30 Suppl 1:54–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauro MD, Thomas B. Tyrphostin attenuates platelet-derived growth factor-induced contraction in aortic smooth muscle through inhibition of protein tyrosine kinase(s) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1119–1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk BC, Alexander RW, Brock TA, Gimbrone MAJ, Webb RC. Vasoconstriction: a new activity for platelet-derived growth factor. Science. 1986;232:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.3485309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taya S, Inagaki N, Sengiku H, Makino H, Iwamatsu A, Urakawa I, Nagao K, Kataoka S, Kaibuchi K. Direct interaction of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor with leukemia-associated RhoGEF. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:809–820. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata Y, Amano M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-Rho-kinase pathway in smooth muscle contraction and cytoskeletal reorganization of non-muscle cells. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:32–39. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzer G. Invited review: regulation of myosin phosphorylation in smooth muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:497–503. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMLYO ANDREWP, SOMLYO AVRILV. Ca2+ Sensitivity of Smooth Muscle and Nonmuscle Myosin II: Modulated by G Proteins, Kinases, and Myosin Phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Rho/Rho-kinase mediated signaling in physiology and pathophysiology. J Mol Med. 2002;80:629–638. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosens R, Meurs H, Bromhaar MM, McKay S, Nelemans SA, Zaagsma J. Functional characterization of serum- and growth factor-induced phenotypic changes in intact bovine tracheal smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:459–466. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosens R, Nelemans SA, Hiemstra M, Grootte Bromhaar MM, Meurs H, Zaagsma J. Insulin induces a hypercontractile airway smooth muscle phenotype. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;481:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Itoh H, Lederis K, Hollenberg MD. Contraction of guinea pig trachea by epidermal growth factor--urogastrone. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;66:1308–1312. doi: 10.1139/y88-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasuhara Y, Munakata M, Sato A, Amishima M, Homma Y, Kawakami Y. Mechanisms of epidermal growth factor-induced contraction of guinea pig airways. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;296:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosens R, Schaafsma D, Grootte Bromhaar MM, Vrugt B, Zaagsma J, Meurs H, Nelemans SA. Growth factor-induced contraction of human bronchial smooth muscle is Rho-kinase-dependent. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;494:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amishima M, Munakata M, Nasuhara Y, Sato A, Takahashi T, Homma Y, Kawakami Y. Expression of epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor immunoreactivity in the asthmatic human airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1907–1912. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9609040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CC, Chu HW, Westcott JY, Tucker A, Langmack EL, Sutherland ER, Kraft M. Airway fibroblasts exhibit a synthetic phenotype in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung TF, Wong GW, Ko FW, Li CY, Yung E, Lam CW, Fok TF. Analysis of Growth Factors and Inflammatory Cytokines in Exhaled Breath Condensate from Asthmatic Children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;137:66–72. doi: 10.1159/000085106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Takada Y, Miyamoto S, MitsuiSaito M, Karaki H, Misawa M. Augmented acetylcholine-induced, Rho-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of bronchial smooth muscle contraction in antigen-induced airway hyperresponsive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:597–600. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Sakai H, Suenaga H, Kamata K, Misawa M. Enhanced Ca2+ sensitization of the bronchial smooth muscle contraction in antigen-induced airway hyperresponsive rats. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1999;106:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma D, Gosens R, Bos IS, Meurs H, Zaagsma J, Nelemans SA. Allergic sensitization enhances the contribution of Rho-kinase to airway smooth muscle contraction. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:477–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick E, Hackel PO, Prenzel N, Ullrich A. The EGF receptor as central transducer of heterologous signalling systems. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:408–412. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ilasaca M. Signaling from G-protein-coupled receptors to mitogen-activated protein (MAP)-kinase cascades. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:269–277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer OM, Streit S, Hart S, Ullrich A. Beyond Herceptin and Gleevec. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:490–495. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(03)00082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LL, Wartmann M, Lin AY, Knopf JL, Seth A, Davis RJ. cPLA2 is phosphorylated and activated by MAP kinase. Cell. 1993;72:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90666-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Shimomura E, Iwanaga T, Shiraishi M, Shindo K, Nakamura J, Nagumo H, Seto M, Sasaki Y, Takuwa Y. Essential role of rho kinase in the Ca2+ sensitization of prostaglandin F(2alpha)-induced contraction of rabbit aortae. J Physiol. 2003;546:823–836. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher MD, Abe MK, Chao TS, Jain M, Green JM, Solway J, Rosner MR, Hershenson MB. Role of MAP kinase activation in bovine tracheal smooth muscle mitogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L894–L901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.6.L894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosens R, Schaafsma D, Meurs H, Zaagsma J, Nelemans SA. Role of Rho-kinase in maintaining airway smooth muscle contractile phenotype. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;483:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen LJ, Wattie J, Lu-Chao H, Tazzeo T. Muscarinic excitation-contraction coupling mechanisms in tracheal and bronchial smooth muscles. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1142–1151. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis BL, Holub BJ, Troyer DA, Skorecki KL. Epidermal growth factor stimulates phospholipase A2 in vasopressin-treated rat glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J. 1988;256:469–474. doi: 10.1042/bj2560469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornfeldt KE, Campbell JS, Koyama H, Argast GM, Leslie CC, Raines EW, Krebs EG, Ross R. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway can mediate growth inhibition and proliferation in smooth muscle cells. Dependence on the availability of downstream targets. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:875–885. doi: 10.1172/JCI119603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulven I, Palmier B, Robin P, Vacher M, Harbon S, Leiber D. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates phospholipase C-gamma 1, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and arachidonic acid release in rat myometrial cells: contribution to cyclic 3',5'-adenosine monophosphate production and effect on cell proliferation. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:496–506. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.2.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndukwu IM, White SR, Leff AR, Mitchell RW. EP1 receptor blockade attenuates both spontaneous tone and PGE2-elicited contraction in guinea pig trachealis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L626–L633. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.3.L626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Amsterdam RG. Beta-adrenoceptor responsiveness in non-allergic and allergic airways - An in-vitro approach. 1991. pp. 68–69.

- Shum WW, Le GY, Jones RL, Gurney AM, Sasaki Y. Involvement of Rho-kinase in contraction of guinea-pig aorta induced by prostanoid EP3 receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1449–1461. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley SL, Hartney JM, Erikson CJ, Jania C, Nguyen M, Stock J, McNeisch J, Valancius C, Panettieri RAJ, Penn RB, Koller BH. Receptors and pathways mediating the effects of prostaglandin E2 on airway tone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L599–L606. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00324.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalli A, Janssen LJ. Augmentation of bovine airway smooth muscle responsiveness to carbachol, KCl, and histamine by the isoprostane 8-iso-PGE2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1035–L1041. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00138.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Smith WL, Narumiya S. International Union of Pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: properties, distribution, and structure of the receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly CR, Williams GW, Sharif NA. Real-time intracellular Ca2+ mobilization by travoprost acid, bimatoprost, unoprostone, and other analogs via endogenous mouse, rat, and cloned human FP prostaglandin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:238–245. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BW, Klimko P, Crider JY, Sharif NA. AL-8810: a novel prostaglandin F2 alpha analog with selective antagonist effects at the prostaglandin F2 alpha (FP) receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1278–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sametz W, Hennerbichler S, Glaser S, Wintersteiger R, Juan H. Characterization of prostanoid receptors mediating actions of the isoprostanes, 8-iso-PGE(2) and 8-iso-PGF(2alpha), in some isolated smooth muscle preparations. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1903–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay S, Sharma HS. Autocrine regulation of asthmatic airway inflammation: role of airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2002;3:11. doi: 10.1186/rr160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]