Abstract

Chemobiosynthesis (J. R. Jacobsen, C. R. Hutchinson, D. E. Cane, and C. Khosla, Science 277:367-369, 1997) is an important route for the production of polyketide analogues and has been used extensively for the production of analogues of 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6-dEB). Here we describe a new route for chemobiosynthesis using a version of 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS) that lacks the loading module. When the engineered DEBS was expressed in both Escherichia coli and Streptomyces coelicolor and fed a variety of acyl-thioesters, several novel 15-R-6-dEB analogues were produced. The simpler “monoketide” acyl-thioester substrates required for this route of 15-R-6-dEB chemobiosynthesis allow greater flexibility and provide a cost-effective alternative to diketide-thioester feeding to DEBS KS1o for the production of 15-R-6-dEB analogues. Moreover, the facile synthesis of the monoketide acyl-thioesters allowed investigation of alternative thioester carriers. Several alternatives to N-acetyl cysteamine were found to work efficiently, and one of these, methyl thioglycolate, was verified as a productive thioester carrier for mono- and diketide feeding in both E. coli and S. coelicolor.

The polyketide class of natural products comprises numerous compounds with great diversity in both structure and biological activity. Many of these compounds have found uses in medicine and agriculture (20, 26). The increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens has made the search for new and better antimicrobial compounds more urgent. One traditional avenue of research is the chemical modification of existing antibiotics to generate more-potent molecules. For example, the macrolide antibiotic erythromycin can be chemically converted to semisynthetic derivatives called ketolides (e.g., ABT773, telithromycin) that are active against macrolide-resistant bacteria.

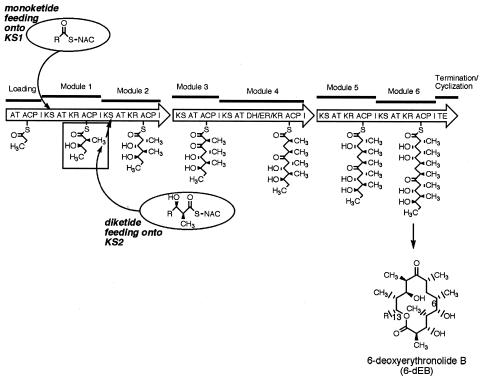

The erythromycin precursor polyketide 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6-dEB) is produced from one propionyl-coenzyme A (CoA) starter unit and six (2S)-methylmalonyl-CoA extender units by a series of condensation and reduction steps catalyzed by 6-dEB synthase (DEBS) (Fig. 1) (5). The loading module of DEBS consists of an acyltransferase (ATL) and an acyl carrier protein (ACPL). Starter unit selection is determined by the specificity of the ATL, and, with DEBS, propionate is the preferred starter unit. Attempts to change the specificity of the loading module by genetic engineering have produced strains that are able to produce specific 6-dEB and erythromycin analogues such as 14-nor erythromycin (16, 17, 28), although typically at much reduced titers. Chemobiosynthesis, the feeding of a diketide-S-N-acetyl cysteamine (SNAC) or diketide-S-N-propionyl cysteamine (SNPC) to a version of DEBS deficient in the first ketosynthase (KS) step, is an important and established route for the production of 6-dEB analogues (6, 9). This requires the expression of a modified DEBS1 which either carries an inactivating mutation in KS1 (DEBS1 KS1O) (9) or completely lacks both the loading module and module 1 of DEBS1 (DEBS1-mod2) (8, 23, 25). Subsequent bioconversion and chemical modification of these compounds to bioactive erythromycin analogues have led to the discovery of several promising new antibacterial compounds. The advantages of the chemobiosynthesis approach over genetic manipulation of loading module specificity are twofold. Firstly, a variety of different diketide-SNAC units can be fed to generate many 6-dEB analogues from a single strain, and, secondly, titers with the chemobiosynthesis process remain high, over 1 g/liter (4). A disadvantage of the chemobiosynthetic process is the cost of chemical synthesis of the fed diketide-SNAC, which can significantly impact the overall cost of producing compounds.

FIG. 1.

Chemobiosynthesis for 6-dEB analogue production. In the native DEBS enzyme, biosynthesis is initiated with the loading of propionate onto ACPL by the loading module AT. In the absence of an active loading module, this step can be bypassed by direct loading of acyl-thioesters onto KS1 (monoketide feeding). In a system that lacks KS1 activity, i.e., the previously established route for chemobiosynthesis, biosynthesis is initiated via direct loading of KS2 with a suitable diketide acyl-thioester.

Heterologous expression of the DEBS subunits, DEBS1, DEBS2, and DEBS3, in Streptomyces coelicolor has led to the development of strains and conditions that allow high levels of production of 6-dEB. More recently, heterologous expression of DEBS in Escherichia coli has achieved production levels higher than 1 g 6-dEB/liter (13, 19). Furthermore, metabolic engineering led to the development of an E. coli strain that was able to produce 15-methyl (Me)-6-dEB via a direct fermentation process (11). However, the utility of this system was limited both by low titers and its specificity for 15-Me-6-dEB, with no other analogues produced in considerable amounts. In this study we investigated whether shorter acyl-thioesters could be utilized as substrates by a DEBS enzyme deficient in starter unit loading. This approach greatly simplified the chemical synthesis of the acyl-thioester, as seen by comparing the substrates butyryl-SNAC (no stereocenters) and (2S, 3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxy-hexanonyl-SNPC (“propyl-diketide”-SNPC, with two stereocenters), both of which are converted by their respective engineered DEBS enzymes to 15-Me-6-dEB (Fig. 1). Previously only acyl-SNAC and acyl-SNPC thioesters have been utilized for chemobiosynthesis with DEBS for the production of 6-dEB analogues and triketide lactones, and both were found to work with equivalent efficiencies (14, 25). Having established that butyryl-SNAC was incorporated efficiently into the polyketide synthase (PKS), we produced several novel 15-R-6-dEB analogues from alternative acyl-SNAC thioesters and also investigated whether we could replace the costly cysteamine thioester moiety with a more economical alternative. We identified a cost-effective alternative thioester carrier, methyl thioglycolate, which was found to substitute efficiently for SNAC in both monoketide- and diketide-fed processes in E. coli and S. coelicolor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction. (i) E. coli plasmids.

The ColE1-based expression vector for DEBS2 and DEBS3, pBP130, has been described previously (24). The version of DEBS1 in which the ATL-ACPL was deleted was isolated as an NdeI/SpeI fragment from pKOS131-043a (see below) and used to replace the native DEBS1 NdeI/SpeI gene fragment in the E. coli expression plasmid pKOS173-158 (19). The final vector, pKOS214-175, is a kanamycin-resistant ColEI-based plasmid with the DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) gene under T7 promoter control. The DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) gene was subsequently subcloned from pKOS214-175 as a BglII/EcoRI fragment into pKOS173-176 (19), replacing DEBS3. This plasmid, pKOS207-144, is a streptomycin-resistant colD/incQ-based plasmid with the DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) gene under T7 promoter control.

(ii) Streptomyces plasmids.

To delete the DEBS loading module, a region encoding the N-terminal portion of DEBS KS1 was amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, pCK12 as template, and the primer pair eKS1-f (ATTCGCTAGCGGCGAACCGGTCGCGGTC) and eKS1-r (TACTGTACATCGCCAGCACCATCTTGATC), where restriction sites are indicated by underlining. The PCR product was cut with NheI plus BsrGI and cloned in the corresponding sites of Litmus38 (New England Biolabs). The resulting plasmid was cut with MfeI plus NheI, and a short linker was ligated between these sites to give pKOS131-038A. The sequence that resulted just upstream of KS1 is CAATTGACCAACGAAGCGGCTAGCGGCGAACCGGTCGCGGTC, which encodes QLTNEAASGEPVAV. The 1,000-bp MfeI/BsiWI fragment of pKOS131-038A was used to replace the loading module fragment in the DEBS expression vector pKOS011-077. The resulting plasmid, pKOS131-043a, encodes a version of DEBS1 that has the coding region for the natural N terminus of DEBS1 but with the loading domain AT and ACP deleted.

All PCR generated fragments were verified by sequence analysis.

Production of 6-dEB analogues in E. coli.

E. coli K207-3 (19) [F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) ΔprpRBCD::PT7-sfp-PT7-prpE ygfG::PT7-accA1-PT7-pccB panDS25A] was used for heterologous polyketide production. K207-3, a modified version of BL21(DE3), is capable of generating methylmalonyl-CoA when fed propionate through overexpression of propionyl-CoA ligase (encoded by prpE) and propionyl-CoA carboxylase (encoded by accA1 and pccB). The strain also contains a chromosomal copy of sfp, a 4-phosphopantetheine transferase gene necessary for phosphopantetheinylation of PKSs.

E. coli strains were grown for 6-dEB production as described previously (19). Acyl-thioesters for chemobiosynthesis were added upon induction of the expression of T7 RNA polymerase. Unless otherwise stated, acyl-thioesters were added to the media to give a final concentration of 3.8 mM. Sample broths for 6-dEB analysis were extracted with ethyl acetate and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)/mass spectrometry (MS) as described previously (19). The results shown are the averages of a minimum of two independent fermentations.

Production of 6-dEB analogues in S. coelicolor.

S. coelicolor CH999 was used as a host strain for polyketide production. Plasmids were introduced into S. coelicolor by polyethylene glycol-assisted protoplast transformation (12).

(i) Comparison of monoketide and diketide feeding.

Seed cultures of S. coelicolor CH999 strains cotransformed with pKOS146-145 (7) and pKOS131-043a were prepared by inoculation of a frozen cell culture in 3 ml of Trypticase soy broth (12) in 50-ml culture tubes containing glass beads. The cultures were grown at 30°C for 3 days at 200 rpm. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of seed culture were used to inoculate 35 ml of R6 liquid medium (8) in 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks. The flasks were incubated at 30°C with shaking at 180 rpm. Butyryl-SNAC or “propyl diketide”-SNPC was added at 1 g/liter at 24 h. Cultures were harvested after 7 days and analyzed by HPLC/MS as previously described (4).

(ii) Diketide feeding for comparison of thioester carrier.

A seed culture of S. coelicolor OP/pKOS011-26/pBOOST (4) was prepared by inoculation of a frozen cell culture into 35 ml SC-VM6-1 (25) media in a 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flask and was grown at 30°C for 3 days at 180 rpm. Aliquots (0.7 ml) of seed culture were used to inoculate 35 ml of SC-VM6-2 (pH 7) media (25) in 250-ml baffled Erlenmeyer flasks. The flasks were incubated at 30°C with shaking at 180 rpm. Diketide-thioester was added at 1 g/liter at 48 and 96 h. After 9 days samples were diluted 1:1 with methanol and extracted for 1 h with shaking. Following centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min), the supernatant was analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)/MS as previously described (15).

Synthesis of acyl-thioesters. (i) General procedure for preparing monoketide-thioesters from acid chlorides.

Triethylamine (1.2 eq) was added to a 0.5 M solution of the desired thiol (1 eq) in dry CH2Cl2. The acid chloride (1 eq) was added dropwise over several minutes, and the reaction mixture was stirred between 2 and 24 h, during which time a white precipitate formed. Upon completion of the reaction, the mixture was poured into 1 M HCl, extracted with ethyl acetate, and washed with water and brine. The organic layers were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and reduced in vacuo to yield an oil that was sufficiently pure for further use.

(ii) General procedure for preparing monoketide-thioesters from carboxylic acids.

1-[3-(Dimethylamino)propyl]-1-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (3 eq) was added to a 0.13 M solution of thiol (1 eq) in dry CH2Cl2 to form a cloudy mixture. Upon stirring, the reaction mixture became clear. To this solution was added the desired carboxylic acid (2.5 eq) followed by dimethylaminopyridine (0.1 eq). The reaction mixture was stirred for approximately 15 h, after which the reaction was shown to be complete by thin-layer chromatography. The product was concentrated in vacuo and purified by silica gel chromatography (acetone/hexanes).

(iii) Thiolysis of diketide-benzoxazolidinone with methyl thioglycolate.

A 25% (by weight) solution of sodium methoxide in methanol (0.18 ml, 0.80 mmol, 1 eq) was added to a solution of methyl thioglycolate (0.072 ml, 0.80 mmol, 1 eq) in methanol (4 ml). After 40 min, acetic acid (0.037 ml, 0.64 mmol, 0.8 eq) was added to the solution. A solution of 3-hydroxy-2-methylpentanoate benzoxazolidinone (0.200 g, 0.80 mmol, 1 eq) in methanol (2 ml) was added dropwise to the thiolate solution over 4 min. The solution was stirred for 1 h and quenched with acetic acid (0.023 ml, 0.40 mmol, 0.5 eq). The solution was partitioned between ethyl acetate (40 ml) and water (10 ml). The organic layer was washed with brine (10 ml, 1×), dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to yield an oily white solid. The crude material was purified by silica flash chromatography (ethyl acetate/hexanes). Fractions containing a mixture of benzoxazolidinone and thioester were washed with warm hexanes (10 ml, 3×) to remove the thioester. The fractions were combined and concentrated in vacuo to yield the racemic anti-diketide-thioester (0.1367 g, 77% yield) as a clear oil.

NMR data.

1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data are as follows: (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.87 (ddd, 1 H, J = 8.2, 4.4, 4.1 Hz), 3.66 (s, 3 H), 3.64 (d, 2 H, J = 4.4 Hz), 2.67 (dq, 1 H, J = 4.1 Hz), 1.46 to 1.26 (m, 4 H), 1.17 (d, 3 H, J = 6.8 Hz), 0.85 (t, 3 H, J = 6.8). 13C NMR data are as follows: (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 201.49, 169.14, 71.85, 53.31, 52.67, 36.22, 30.81, 18.99, 13.77, 11.27; HRMS m/z calculated for C9H16O4NaO 243.006674, found 243.06615.

RESULTS

Altered DEBS1 proteins will accept butyryl-SNAC as a substrate for production of 15-Me-6-dEB.

In the chemobiosynthetic procedure previously established for DEBS, a derivative of DEBS with a KS1 mutation (KS1°) is fed a diketide-thioester that is directly loaded onto module 2 and processed to produce 15-R-6-dEB (Fig. 1) (9). We examined if a simpler monoketide-thioester could be loaded onto module 1 of a DEBS derivative that lacked the loading domain [Δ(ATL-ACPL)] but retained an active KS1.

The engineered DEBS1 gene on pKOS207-144 [Δ(ATL-ACPL)] was expressed in E. coli strain K207-3 together with DEBS2 and DEBS3 from pBP130 (19, 24). This strain, expressing the modified DEBS1 protein, produced significant titers of 15-Me-6-dEB when fed butyryl-SNAC (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that KS1 of DEBS1 is able to accept acyl-thioesters as substrates in the absence of a functional loading module. A detectable amount of 6-dEB was also found in the presence or absence of exogenous thioester. This demonstrates that propionyl-CoA is able to directly load onto KS1 of DEBS1. A similar result has previously been reported using DEBS1 loading domain mutants in the natural erythromycin producer Saccharopolyspora erythraea (16, 22).

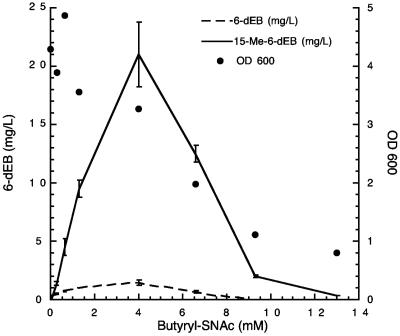

FIG. 2.

Optimization of butyryl-SNAC feed level for 15-Me-6-dEB production with DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) in E. coli. Error bars show the standard errors. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Using K207-3 expressing DEBS1-Δ(ATL-ACPL), DEBS2, and DEBS3, the effect on titers of varying the butyryl-SNAC feed level was investigated (Fig. 2). Titers of 15-Me-6-dEB increased to a maximum of 21 mg/liter (0.05 mM) at a feed level of 3.8 mM butyryl-SNAC. Higher concentrations of butyryl-SNAC resulted in a reduction in titers as well as a reduction in the final optical density at 600 nm of the cultures, indicating that butyryl-SNAC is growth inhibitory at high concentrations. This has been noted with other thioester-fed processes, and toxicity has been effectively overcome using a continuous feed of substrate such that the inhibitory concentration is never reached (4, 15).

The engineered DEBS1 protein will accept alternative acyl-SNACs for novel metabolite production.

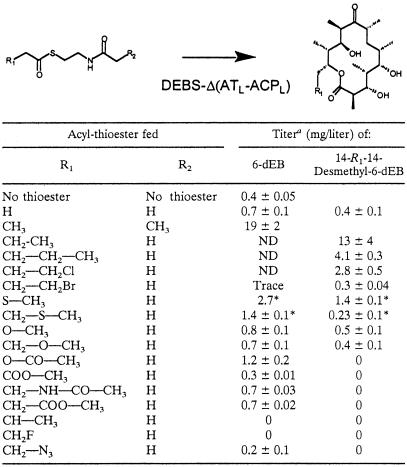

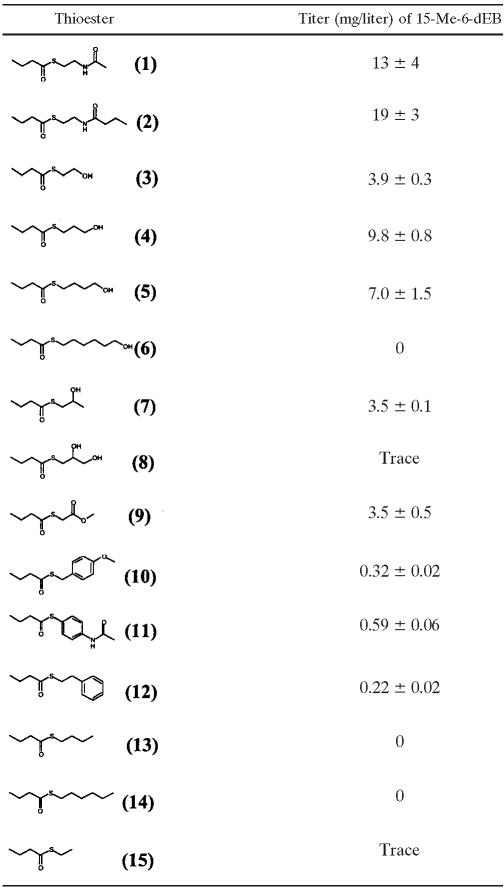

Different acyl-SNAC thioesters were tested for their ability to be processed by the engineered DEBS system into novel 6-dEB analogues (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The feed level of each thioester tested was adjusted to 3.8 mM, the molar equivalent of butyryl-SNAC that gave the maximum titer, as shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 1.

Production of 6-dEB analogues by chemobiosynthesis with DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) in E. coli

Titers reported are estimates using authentic 15-Me-6-dEB as a standard. *, titer is a rough estimate based on analysis of parent ions by MS since compound did not resolve from 6-dEB by LC. ND, not determined.

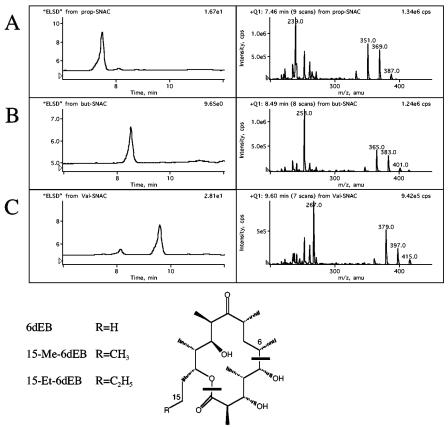

FIG. 3.

HPLC/MS analysis of extracts from strains producing 6-dEB, 15-Me-6-dEB, and 15-Et-6dEB. The left panel of each row shows the evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD) chromatogram of E. coli extracts, and the right panel shows the mass spectrum for the peak. (A) Extract from strain fed propyl-SNPC. The mass spectrum shows pseudomolecular ions [M+1] of 387, [M+1-H2O] of 369, and [M+1-2H2O] of 351 and a C6-C15 fragment of 239, consistent with 6-dEB (1). The origin of the major C6-C15 fragment is indicated by solid bars in the structure. (B) Extract from a strain fed butyryl-SNAC. The mass spectrum shows pseudomolecular ions [M+1] of 401, [M+1-H2O] of 383, and [M+1-2H2O] of 365 and a C6-C16 fragment of 253, consistent with 15-Me-6-dEB. (C) Extract from a strain fed valeryl-SNAC. The mass spectrum shows pseudomolecular ions [M+1] of 415, [M+1-H2O] of 397, and [M+1-2H2O] of 379 and a C6-C17 fragment of 267, consistent with 15-Et-6-dEB.

Culture extracts were analyzed by LC/MS, and the fragmentation patterns were used to identify the novel compounds. Figure 3 shows LC/MS data for strains fed propionyl-SNPC, butyryl-SNAC, and valeryl-SNAC, showing the production of compounds with mass spectra consistent with the expected products 6-dEB, 15-Me-6-dEB, and 15-ethyl (Et)-6-dEB. In this manner 15-chloromethyl-6-dEB, 15-bromomethyl-6-dEB, 14-methylthio-6-dEB, 14-nor-6-dEB, 14-methoxy-6-dEB, 15-methylthio-6-dEB, and 15-methoxy-6-dEB were shown to be produced in detectable amounts (Table 1). Use of several thioesters resulted in no new product being observed, and use of two of these, fluoropropionyl-SNAC and crotonyl-SNAC, also resulted in the loss of detectable 6-dEB. The loss of background levels of 6-dEB from direct loading of propionyl-CoA onto KS1 implies that fluoropropionyl-SNAC and crotonyl-SNAC are inhibitors of either the PKS- or acyl-CoA-producing enzymes. No reduction in the growth of the cultures was noted, indicating that the lack of 6-dEB production was not due to general toxicity. It is likely that fluoropropionyl-SNAC and crotonyl-SNAC specifically inactivate the PKS by a mechanism similar to that reported for inhibition of fatty acid synthases (FAS) and other acyl-CoA-utilizing enzymes by chloropropionyl-CoA and acrylyl-SNAC (18). Inhibition of the functionally similar FAS by chloropropionyl-CoA is due to alkylation of a reactive cysteine and the pantetheinyl sulfhydryl (18).

When the acyl group of the thioester was increased from C3 (propionyl) to C4 (butyryl) to C5 (valeryl), a clear reduction in product formation was observed (Table 1). An exception was observed with acetyl-SNAC, which gave lower titers than those observed with propionyl-SNAC. This result may be related to the observation that 14-desmethyl-6-dEB is not produced when the wild-type DEBS genes are expressed in E. coli (11), despite the known ability of DEBS1 to utilize acetyl-CoA as a starter unit when expressed in S. coelicolor (10).

Conversion of these new 6-dEB analogues to their corresponding erythromycin analogues can be achieved by oxidation and glycosylation using a modified strain of S. erythraea (2). Alternatively, the recent development of an E. coli strain able to produce erythromycin (21) will allow production of these erythromycin analogues directly in E. coli.

Expression of engineered DEBS genes in Streptomyces coelicolor.

Large-scale production of 6-dEB analogues is currently achieved by fermentation of a strain of S. coelicolor that expresses a KS1° version of the DEBS genes and is fed appropriate diketide-thioesters. In order to test the loading module construct in this system, the engineered DEBS1 gene was cloned into a Streptomyces expression vector together with the DEBS2 and DEBS3 genes to produce pKOS131-043a [Δ(ATL-ACPL)]. This plasmid was then introduced into S. coelicolor CH999 and tested for 15-Me-6-dEB production when the strain was fed either butyryl-SNAC or “propyl diketide”-SNPC using the same feeding schedule (Table 2). Both thioesters were converted to their respective polyketide products in this strain. Titers of 15-Me-6-dEB from the monoketide- and diketide-fed processes in S. coelicolor were comparable, with the simpler and less costly monoketide-fed process achieving the same productivity as the diketide-fed process. These data show that transferring the engineered DEBS gene to the higher-producing S. coelicolor system mimics the results found in E. coli but with the higher titers normally associated with the S. coelicolor expression system. It would be expected that optimizing levels of butyryl-SNAC fed for S. coelicolor would raise titers further.

TABLE 2.

6-dEB and 15-Me-6-dEB production by a strain of Streptomyces coelicolor expressing a version of DEBS, DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL), lacking the loading module

| Fed thioester | Titer (mg/liter) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 6-dEB | 15-Me-6-dEB | |

| None | 16 | 0 |

| “Propyl diketide”-SNPC | 15 | 160 |

| Butyryl-SNAC | 16 | 120 |

Identification of alternative thioester carriers for use in chemobiosynthesis.

The SNAC or SNPC thiols currently used to prepare thioesters are costly and have been projected to represent a significant fraction of the overall production costs of 15-R-6-dEB analogues. The facile synthesis of monoketide thioester feedstocks allowed us to test alternative thioester carriers (i.e., alternatives to SNAC/SNPC) to determine whether these could be used in a chemobiosynthetic process (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Alternative butyryl-thioesters fed to DEBS1 Δ(ATL-ACPL) in E. coli for chemobiosynthesis of 15-Me-6-dEB

A number of the thioesters tested were recognized by DEBS Δ(ATL-ACPL) and converted to 15-Me-6-dEB (Table 3). The simplest thioesters tested, ethyl thiobutyrate (structure 15), hexyl thiobutyrate (structure 14), and butyl thiobutyrate (structure 13), failed to give quantifiable titers of 15-Me-6-dEB. However, of 13 thioesters tested, 8 were found to be efficient substrates for the modified DEBS. The mercaptoalcohol-based compounds (thioesters 3 to 8) were most successful for 15-Me-6-dEB production but were found to be growth inhibitory to the host strains, as measured by final optical density at 600 nm. For this reason, methyl thioglycolate, the carrier for methyl S-butyrylthioglycolate (structure 9), was selected for further investigation as a thioester carrier.

Diketide feeding with alternatives to SNAC.

Methyl S-[(2R*,3S*)-3-hydroxy-2-methylpentanoyl]thioglycolate (“natural diketide”- thioglycolate) was then synthesized to compare with the diketide feeding strategy currently used for the large-scale production of 15-R analogues of 6-dEB. In vitro experiments comparing “natural diketide” and “propyl diketide” thioesters as substrates for purified DEBS have shown that the enzyme has a modest preference for the “propyl diketide” thioester over the “natural diketide” thioester (3, 27). The “natural diketide”-thioglycolate and the “propyl diketide”-SNPC were first compared in the E. coli strain expressing DEBS1-mod2 and DEBS2 and -3 (Table 4). The data in Table 4 demonstrate that, under the conditions used, the two diketides are equivalent. However, the cost of the methyl thioglycolate used in the synthesis of the diketide thioester is <10% that of SNPC or SNAC (Aldrich; 2001 catalog).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of SNPC and methyl thioglycolate as thioester carriers for diketide feeding in E. coli and S. coelicolor

| Fed thioester | Titer (mg/liter) of 15-R-6dEB for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. coelicolor | |

| “Propyl diketide”-SNPC | 30 ± 6 | 371 ± 4 |

| “Natural diketide”-thioglycolate | 23 ± 1.5 | 245 ± 7 |

The “natural diketide”-thioglycolate was also tested with an S. coelicolor strain expressing a KS1° version of DEBS. Titers obtained using the “natural diketide”-thioglycolate were 66% of those found from feeding “propyl diketide”-SNPC (Table 4). This is remarkable considering that the conditions used were those optimized for “propyl diketide”-SNPC feeding and could presumably be optimized further for diketide- thioglycolate feeding.

DISCUSSION

We describe here two significant improvements to the standard chemobiosynthetic approach for the production of ketolide precursors: an engineered DEBS1 protein that utilizes simpler monoketide thioesters and the replacement of the SNAC/SNPC thioester carrier with an inexpensive alternative. Currently 15-R analogues of 6-dEB are made by feeding diketide thioesters to an S. coelicolor strain expressing a KS1° version of the DEBS genes (4). Chemical synthesis of the diketide thioester is projected to represent a significant fraction of the total cost of analogue production via this route. Previous attempts to make 6-dEB analogues by either altering the loading module specificity (16, 17) or metabolic engineering of the host (11) have been limited by low titers and the possible production of only a limited number of potential analogues. The engineered DEBS protein lacking the loading module addresses both of these issues. In shake flask fermentations, the titers of 15-Me-6-dEB obtained by feeding the ATL-ACPL deletion strain butyryl-SNAC are similar to those of 6-dEB obtained from expressing the wild-type DEBS in E. coli (22.5 mg/liter) (19). High-density E. coli fermentations currently yield >1 g 6-dEB/liter (13). Experience with other thioester-fed processes (4) leads us to believe that scale-up of the butyryl-SNAC-fed process would yield similar titers of 15-Me-6-dEB. The generation of acyl-thioesters from commercially available acids is facile, and it is thus possible to generate many acyl-thioesters for the production of novel 6-dEB scaffolds. Nine 6-dEB analogues have been produced with this system, demonstrating the flexibility of this approach. The utility of the DEBS1 loading module constructs was verified in S. coelicolor, where feeding of butyryl-SNAC led to high titers of 15-Me-6-dEB (Table 2).

The SNAC/SNPC moiety contributes significantly to the cost of production of the diketide-thioester. Therefore, alternative thiols to SNAC/SNPC for 15-Me-6-dEB production were tested, and, of 13 tested, 8 gave a quantifiable product. One of these, methyl thioglycolate, was selected as a particularly promising candidate, supporting the highest titers with minimal toxicity, while reducing the cost of production of the diketide-thioester. Methyl thioglycolate was validated as a productive carrier for diketide feeding to KS1° DEBS in both E. coli and S. coelicolor. Chemobiosynthesis via feeding “monoketide”-thioesters to the version of DEBS that lacks the loading module has thus proven to be a productive and flexible strategy to rapidly generate 6-dEB analogues and to explore the nature of the requirements for the thioester carrier.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Carney and Nina Viswanathan for assistance with LC-MS analysis. We also thank Hugo Gramajo and Timothy Leaf for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashley, G. W., and J. R. Carney. 2004. API-mass spectrometry of polyketides. II. Fragmentation analysis of 6-deoxyerythronolide B analogs. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 57:579-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carreras, C., S. Frykman, S. Ou, L. Cadapan, S. Zavala, E. Woo, T. Leaf, J. Carney, M. Burlingame, S. Patel, G. Ashley, and P. Licari. 2002. Saccharopolyspora erythraea-catalyzed bioconversion of 6-deoxyerythronolide B analogs for production of novel erythromycins. J. Biotechnol. 92:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuck, J. A., M. McPherson, H. Huang, J. R. Jacobsen, C. Khosla, and D. E. Cane. 1997. Molecular recognition of diketide substrates by a beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase domain within a bimodular polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 4:757-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai, R. P., T. Leaf, Z. Hu, C. R. Hutchinson, A. Hong, G. Byng, J. Galazzo, and P. Licari. 2004. Combining classical, genetic, and process strategies for improved precursor-directed production of 6-deoxyerythronolide B analogues. Biotechnol. Prog. 20:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donadio, S., M. J. Staver, J. B. McAlpine, S. J. Swanson, and L. Katz. 1991. Modular organization of genes required for complex polyketide biosynthesis. Science 252:675-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frykman, S., T. Leaf, C. Carreras, and P. Licari. 2001. Precursor-directed production of erythromycin analogs by Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 76:303-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu, Z., D. A. Hopwood, and C. R. Hutchinson. 2003. Enhanced heterologous polyketide production in Streptomyces by exploiting plasmid co-integration. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 30:516-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu, Z., B. A. Pfeifer, E. Chao, S. Murli, J. Kealey, J. R. Carney, G. Ashley, C. Khosla, and C. R. Hutchinson. 2003. A specific role of the Saccharopolyspora erythraea thioesterase II gene in the function of modular polyketide synthases. Microbiology 149:2213-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobsen, J. R., C. R. Hutchinson, D. E. Cane, and C. Khosla. 1997. Precursor-directed biosynthesis of erythromycin analogs by an engineered polyketide synthase. Science 277:367-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao, C. M., L. Katz, and C. Khosla. 1994. Engineered biosynthesis of a complete macrolactone in a heterologous host. Science 265:509-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy, J., S. Murli, and J. T. Kealey. 2003. 6-Deoxyerythronolide B analogue production in Escherichia coli through metabolic pathway engineering. Biochemistry 42:14342-14348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 13.Lau, J., C. Tran, P. Licari, and J. Galazzo. 2004. Development of a high cell-density fed-batch bioprocess for the heterologous production of 6-deoxyerythronolide B in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 110:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leaf, T., M. Burlingame, R. Desai, R. Regentin, E. Woo, G. Ashley, and P. Licari. 2002. Employing racemic precursors in directed biosynthesis of 6-dEB analogs. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 77:1122-1126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leaf, T., L. Cadapan, C. Carreras, R. Regentin, S. Ou, E. Woo, G. Ashley, and P. Licari. 2000. Precursor-directed biosynthesis of 6-deoxyerythronolide B analogs in Streptomyces coelicolor: understanding precursor effects. Biotechnol. Prog. 16:553-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long, P. F., C. J. Wilkinson, C. P. Bisang, J. Cortes, N. Dunster, M. Oliynyk, E. McCormick, H. McArthur, C. Mendez, J. A. Salas, J. Staunton, and P. F. Leadlay. 2002. Engineering specificity of starter unit selection by the erythromycin-producing polyketide synthase. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1215-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsden, A. F., B. Wilkinson, J. Cortes, N. J. Dunster, J. Staunton, and P. F. Leadlay. 1998. Engineering broader specificity into an antibiotic-producing polyketide synthase. Science 279:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miziorko, H. M., C. E. Behnke, and F. Ahmad. 1989. Chemical events in chloropropionyl coenzyme A inactivation of acyl coenzyme A utilizing enzymes. Biochemistry 28:5759-5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murli, S., J. Kennedy, L. C. Dayem, J. R. Carney, and J. T. Kealey. 2003. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for improved 6-deoxyerythronolide B production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 30:500-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Hagen, D. 1991. The polyketide metabolites. Ellis Horwood Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 21.Peirú, S., H. Menzella, E. Rodríguez, J. Carney, and H. Gramajo. 2005. Production of the potent antibacterial polyketide erythromycin C in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2539-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereda, A., R. G. Summers, D. L. Stassi, X. Ruan, and L. Katz. 1998. The loading domain of the erythromycin polyketide synthase is not essential for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Microbiology 144(Pt. 2):543-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeifer, B., Z. Hu, P. Licari, and C. Khosla. 2002. Process and metabolic strategies for improved production of Escherichia coli-derived 6-deoxyerythronolide B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3287-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeifer, B. A., S. J. Admiraal, H. Gramajo, D. E. Cane, and C. Khosla. 2001. Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science 291:1790-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regentin, R., J. Kennedy, N. Wu, J. R. Carney, P. Licari, J. Galazzo, and R. Desai. 2004. Precursor-directed biosynthesis of novel triketide lactones. Biotechnol. Prog. 20:122-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh, C. T. 2003. Antibiotics: actions, origins, resistance. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 27.Weissman, K. J., M. Bycroft, A. L. Cutter, U. Hanefeld, E. J. Frost, M. C. Timoney, R. Harris, S. Handa, M. Roddis, J. Staunton, and P. F. Leadlay. 1998. Evaluating precursor-directed biosynthesis towards novel erythromycins through in vitro studies on a bimodular polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 5:743-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson, C. J., E. J. Frost, J. Staunton, and P. F. Leadlay. 2001. Chain initiation on the soraphen-producing modular polyketide synthase from Sorangium cellulosum. Chem. Biol. 8:1197-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]