Abstract

The fungal bean pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum differentiates appressoria in order to penetrate bean tissues. We showed that appressorium development in C. lindemuthianum can be divided into three stages, and we obtained three nonpathogenic strains, including one strain blocked at each developmental stage. H18 was blocked at the appressorium differentiation stage; i.e., no genuine appressoria were formed. H191 was blocked at the appressorium maturation stage; i.e., appressoria exhibited a pigmentation defect and developed only partial internal turgor pressure. H290 was impaired in appressorium function; i.e., appressoria failed to penetrate into bean tissues. Furthermore, these strains could be further discriminated according to the bean defense responses that they induced. Surprisingly, appressorium maturation, but not appressorium function, was sufficient to induce most plant defense responses tested (superoxide ion production and strong induction of pathogenesis-related proteins). However, appressorium function (i.e., entry into the first host cell) was necessary for avirulence-mediated recognition of the fungus.

Plant fungal pathogens differ with respect to the hosts that they can attack and with respect to the organs and tissues that they are able to infect (1). Penetration of the plant tissue is always a crucial step for plant-fungus interactions, as it marks the genuine beginning of the infection cycle and determines the development or lack of development of a disease. In order to overcome the range of barriers that are encountered, fungal penetration strategies are highly diverse. Penetration can be a passive process or an active process. Active penetration through intact plant surfaces occurs via either a thin hypha that is produced directly by the conidium or the extrafoliar mycelium or via a penetration peg produced by an appressorium (10, 31, 46). Several studies of Magnaporthe grisea and Colletotrichum species have indicated that appressorium-mediated direct penetration of the plant cell wall requires the ability to generate physical pressure that acts as a crucial mechanical force (5, 21). This is often concomitant with fungal enzyme activities involved in degradation of the host cuticle and epidermis cell wall barriers (9, 31).

According to cellular studies mainly performed with M. grisea and Colletotrichum species, appressorium development can be subdivided into three distinct developmental stages (46): differentiation, maturation, and function. Differentiation of the appressorium seems to depend on perception of several putative inductive extracellular signals that are physical and/or biological, such as hydrophobicity, surface hardness, and specific chemical compounds (22, 27, 30). It has been demonstrated that cyclic AMP (29), mitogen-activated protein kinases (23, 42, 50-52), and Ca2+/calmodulin-mediated signaling pathways (24, 30, 49) are all directly involved in triggering the morphogenesis program that leads to appressorium formation. Once appressorium differentiation has occurred, appressorium maturation takes place. This involves major biochemical and biophysical modifications, i.e., appressorium cell wall and cytoskeleton modifications (44). Hyaline appressoria rapidly become dark brown as a result of biosynthesis of a thick melanin layer. This phenomenon appears to be essential in M. grisea and Colletotrichum species, as melanin-deficient mutants fail to infect intact plant tissues (8, 28, 38). Besides providing a strengthened cellular structure, deposition of a melanin layer is necessary for development of high internal turgor pressure within the appressorium (10, 11, 21). Data for M. grisea indicate that high turgor pressure is generated through synthesis and accumulation of glycerol, which is mainly derived from glycogen and lipid stores (11, 45). Finally, appressorium function enables the fungus to pierce the cuticle and enter the cell wall of the first infected host cell and allows further fungal development. This involves emergence of a penetration peg into the contact zone between the lower surface of the appressorium and the plant epidermis, termed the appressorium pore. Cytological analysis of appressoria developed in vitro by M. grisea has revealed that polarization of the cytoskeleton precedes penetration peg emergence (7, 35).

During the interaction between a plant and a fungus, a complex molecular dialogue is initiated as soon as the fungal conidium comes into contact with its potential host (14). Plants protect themselves against the threat of fungal pathogens with preexisting structural and chemical defenses, including the plant cell wall (40), waxes, and antimicrobial compounds, such as phytoanticipins and saponins (33, 41). Perception of a fungal pathogen leads to rapid induction of defense responses, including generation of reactive oxygen species, cell wall reinforcement, synthesis of phytoalexins, accumulation of pathogenesis-related proteins (PR proteins), and a change in protein phosphorylation status (20, 41). In most plant-fungus interactions genetically based resistance relies on specific and early recognition of avirulent fungal strains by resistant plants (12). The time course of induction of plant defense and resistance responses during the first steps of the infection is not fully understood yet.

Colletotrichum lindemuthianum is the causal agent of anthracnose disease of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), one of the most serious diseases of common bean in tropical areas. The interaction of these organisms is consistent with the gene-for-gene model (18), and monogenic dominant resistance in common bean cultivars leads to the appearance of localized necrotic spots typical of a hypersensitive response (HR) (32). During infection of a susceptible cultivar, C. lindemuthianum develops a series of well-defined specialized infection structures, including appressoria, infection vesicles, primary hyphae, and finally secondary hyphae that allow colonization of the host tissues (37). In the biotrophic phase, appressorium development takes place around 24 h after conidium germination, and then in the following 2 to 3 days, infection vesicles and primary hyphae are formed. After the switch between biotrophy and necrotrophy, colonization of plant tissues by secondary hyphae occurs. The infection cycle is completed within 7 to 8 days with the production of the new conidial generation. The occurrence of such well-defined specialized structures, which differ in morphology, physiology, and function, indicates that the fungus follows highly organized genetic programs. As a consequence, this model provides a system in which distinct sequential sets of putative fungal elicitors are likely to be available for the host plant to activate its defense responses. However, these signal exchanges are usually considered difficult to study because of the asynchronous development of the infection on plant material, especially at the penetration step. The availability of appropriate mutants blocked at different stages of appressorial development would provide a way to circumvent this problem. Here, we show that three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemuthianum are impaired in appressorium-mediated penetration; each strain is blocked for one of the three stages of appressorium development. We used these three strains, as well as the wild-type strain, to study the hierarchy of bean defense responses triggered during the penetration of plant cells of a susceptible cultivar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and growth conditions.

C. lindemuthianum nonpathogenic strains H290 and H18 originated from wild-type strain UPS9. Nonpathogenic strain H191 originated from strain 9.20, a natural UPS9 derivative (34). Both the UPS9 and 9.20 strains are fully virulent on bean cultivars La Victoire and P12S. As these strains have similar time courses of infection on common bean, UPS9 was used as a control wild-type strain in all studies. Fungal strains were maintained on malt extract agar medium (15 g/liter; Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) at 22°C.

Plant cultivars and infection assays.

Common bean plants were cultivated in growth chambers as described by Dufresne et al. (15). We used five different cultivars, cultivars La Victoire (Tézier, Valence-sur-Rhône, France), P12S, P12R (19), G2333 (36), and Michelite (International Centre of Tropical Agronomy, Colombia). P12S is nearly isogenic with P12R, differing by the absence of the Co-2 resistance gene. La Victoire and P12S cultivars do not contain any known gene for resistance to C. lindemuthianum; and P12R, G2333, and Michelite contain distinct genes for resistance to C. lindemuthianum (Co-2, Co-5/Co4-2, and Co-y, respectively), for which strain UPS9 and its derivatives carry the corresponding avirulence genes.

The lower surfaces of excised cotyledons and 8-day-old whole plantlets were spray inoculated using a suspension containing 5 × 106 conidia/ml. Inoculated leaves were placed on wet filter paper inside petri dishes. Inoculated whole plantlets were covered with plastic caps to maintain high humidity and incubated at 19°C. For inoculation of wounded leaf material, fully developed cotyledons were detached and wounded using Fontainebleau sand (Prolabo, Fontenay sous bois, France) as an abrasive. Six nonwounded leaves and six wounded leaves were used for each C. lindemuthianum strain. Each set of inoculation assays was performed independently three times. Microscopic examinations were performed with excised hypocotyls as described by Bailey et al. (4).

In vitro assays for conidial germination, appressorium differentiation, and estimation of appressorium turgor pressure.

Conidial suspensions were obtained by scraping 6-day-old malt agar petri dish cultures in sterile water. The conidia were recovered by centrifugation at low speed (300 × g) and were rinsed twice with sterile water before use. For germination assays, conidia were suspended in 2 ml of hypocotyl medium (filtrate of 160 g of hypocotyls boiled in 1 liter of water) poured into petri dishes at a final concentration of 105 spores/ml and incubated at 22°C. After 16 h, 200 conidia were examined to calculate the percentage of germinated conidia and germ tubes that had differentiated appressoria. Appressorial turgor pressure was estimated using 36-h-old appressoria differentiated on plastic microscope coverslips (Polylabo, Strasbourg, France). Solutions containing glycerol at concentrations ranging from 1 to 3 M were applied after removal of the hypocotyl medium. The number of collapsed appressoria was determined with a microscope (11, 21). Series of counting experiments were performed three times independently.

Fluorescence microscopy and scanning electron microscopy examination.

Infected bean hypocotyls were harvested 2 and 6 days after inoculation for aniline blue staining of fungal structures developed in planta. Epidermal tissues were peeled, cleared twice for 10 min in 1 M KOH at 70°C, and mounted in 67 mM K2HPO4 (pH 9.0)-0.1% aniline blue. Preparations were examined by epifluorescence microscopy with an Axioskop microscope (filter block [BP 365, FT 395, LP 397]; UV light [340 to 380 nm]; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and images were recorded using a 3CCD color video camera (Sony Deutschland, Köln, Germany).

Appressoria present on hypocotyls 36 h after inoculation were examined by scanning electron microscopy to observe the presence of penetration pores. Appressoria were removed using small pieces of adhesive tape applied to inoculated spots on the surface of hypocotyls. They were frozen on a Pelletier bench (−15°C) and then observed under a partial vacuum using a Hitachi S-3000N scanning electron microscope with an environmental secondary electron detector (90 Pa, 12.0 kV). For each experiment 50 appressoria were observed, and the experiments were performed three times independently.

Common bean PAL, CHS, and PvPR2 gene expression upon inoculation.

Total RNAs were isolated following an infection time course using a hot phenol extraction method. Four leaves were randomly sampled and harvested for each time. Briefly, leaves were ground to a fine powder with liquid nitrogen. The powder was transferred to a tube containing 5 ml of extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM LiCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and 5 ml of phenol preheated to 80°C. After the mixture was vortexed, 5 ml of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24/1, vol/vol) was added. Following 15 min of centrifugation at 9,250 × g, the aqueous phase was removed, and 1 volume of 4 M LiCl was added. After 10 min of incubation at −70°C, the RNA was pelleted by 15 min of centrifugation at 9,250 × g. The RNA pellet was dissolved in 1 ml of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Twenty micrograms of total RNA per sample was loaded on a denaturing gel and transferred to an N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Courtaboeuf, France) by capillary elution as described previously (39).

DNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a random primer labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Courtaboeuf, France). Hybridization was carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (39).

Isolation and analysis of common bean PR protein accumulation after inoculation.

Apoplastic fluids were isolated at various times after inoculation using six leaves per sample, as described by De Witt and Spikman (13). Briefly, infected leaves were vacuum infiltrated with deionized water for 5 min, surface dried, and then centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min. Total soluble proteins were precipitated from the resulting apoplastic fluids using 3 volumes of acetone. PR protein profiles were analyzed following separation on a 12% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel using Coomassie blue for staining.

Superoxide ion detection using NBT staining.

Hypocotyls were inoculated as described above, and samples were taken 24 and 36 h postinoculation. For each time, two hypocotyls were peeled, and the experiment was performed three times. Epidermal tissues were fixed in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 10 mM NaN3 and 0.01% Triton. Staining was done using the same buffer containing 0.1% nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) for 30 min. Hypocotyls were subsequently cleared by 2 min of boiling in ethanol/lactophenol (2/1, vol/vol) and rinsed in 50% ethanol and in water. Samples were observed by light microscopy.

RESULTS

Three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemuthianum are unable to penetrate host tissues due to blocks in appressorium development.

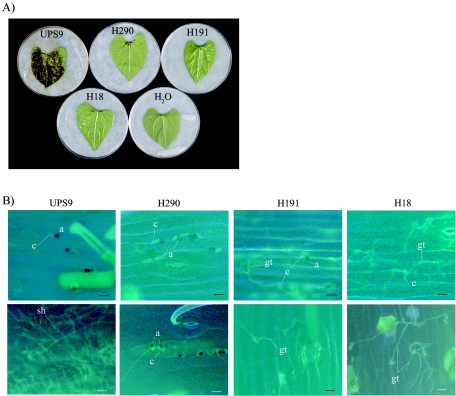

After inoculation of common bean susceptible cultivar La Victoire, three nonpathogenic strains, H290, H191, and H18 were identified. Two of these strains, H290 and H191, have been described previously (15, 34). Strain H18 also was unable to produce anthracnose symptoms on both excised leaves (Fig. 1A) and whole plantlets (data not shown). On wounded leaves, appressorium-mediated penetration was not required in order to gain access to the plant tissue. On wounded leaves, strain H290 was able to induce lesions on veins that never expanded (15), whereas strains H191 and H18 did not produce any anthracnose symptoms (34; data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemuthianum are impaired during appressorium-mediated penetration of bean leaves. (A) Pathogenicity assays for nonpathogenic strains H290, H191, and H18 on cotyledons of La Victoire, a susceptible cultivar of common bean. Photographs were taken 7 days after inoculation. (B) Cytological examination of the three nonpathogenic strains 2 days (upper row) and 6 days (lower row) after inoculation. Conidia were inoculated onto excised hypocotyls, and samples were stained using aniline blue. a, appressorium; c, conidium; gt, germ tube; sh, secondary hyphum. Scale bars = 25 μm.

Cytological studies were also performed with intact infected bean hypocotyls in order to further characterize the in planta phenotypes of the three nonpathogenic strains. Two days after inoculation, appressorium differentiation had occurred for strains H290 and H191. No delay in appressorium differentiation was observed for wild-type strain UPS9 and the H290 and H191 strains. In contrast, the germ tubes of strain H18 that developed displayed extensive branched growth and very rarely had swollen tips. Six days after inoculation, the wild-type strain developed heavy secondary hyphae (Fig. 1B), whereas the three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemuthianum did not develop infection vesicles or primary or secondary hyphae inside epidermal cells (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the lack of pathogenicity of the three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemuthianum resulted from a defect in the penetration stage of bean tissue infection.

In order to investigate more precisely the penetration deficiency of the three nonpathogenic strains, we examined their mycelial growth in vitro, as well as conidial germination and appressorium development. The mycelial growth rate of each of the three nonpathogenic strains on rich agar medium was similar to that of wild-type strain UPS9 (Table 1). However, whereas strains UPS9 and H290 had black-pigmented mycelia, strains H191 and H18 displayed a default in mycelium pigmentation. H191 mycelium was beige, and pigmentation developed in acervuli after 6 days of incubation at 22°C (33); H18 was an albino strain that was never pigmented (data not shown). The rates of conidial germination of the three mutants and the wild-type strain were similar (Table 1), and no significant delay was observed. When conidia of wild-type strain UPS9 were allowed to germinate on a plastic surface in the presence of bean medium, they developed melanized appressoria after 36 h of incubation (Fig. 2A). Strain H290 and the wild-type strain exhibited similar rates of appressorium differentiation (70.8% ± 5.0% and 75.5% ± 5.1%). In contrast, the H191 strain exhibited a significantly reduced rate of appressorium differentiation (34.8% ± 2.7%), as described previously by Parisot et al. (34). The germinating conidia of strain H18 did not differentiate genuine appressoria, and only 1.9% of the germ tubes had swollen tips (Table 1). Strain H290 and the wild-type strain produced short germ tubes, in contrast to the H191 and H18 strains, which produced long germ tubes that began to branch after 16 h of incubation (Fig. 2A). In this respect, the H18 strain displayed a more severe phenotype than the H191 strain. Similar phenotypes were also observed in planta for strains H191 and H18, although quantification of appressorium differentiation was not possible (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 1.

In vitro characteristics of the wild-type strain and three nonpathogenic strainsa

| Strain | Vegetative growth (mm/day)b | Germination rate (%)c | Appressorium differentiation rate (%)c | % of collapsed appressoria with 2 M external glycerold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPS9 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 93.7 ± 0.8 | 75.5 ± 5.1 | 38.5 ± 12.0 |

| H290 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 89.2 ± 2.1 | 70.8 ± 5.0 | 47.7 ± 5.2 |

| H191 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 93.8 ± 1.0 | 34.8 ± 2.7 | 65.8 ± 1.3 |

| H18 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 95.7 ± 2.0 | 0e | NAf |

The values are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments.

Strains were grown on N medium at 22°C for 6 days, and colony diameters were measured.

The conidial germination rate and the appressorium differentiation rate were measured as described in Materials and Methods.

Appressoria were differentiated as described in Materials and Methods, and cytorrhysis experiments were performed using glycerol as the external osmolyte 36 h after inoculation.

Few germinating conidia (1.9 ± 1.7%) had swollen tips of their germ tubes.

NA, not applicable.

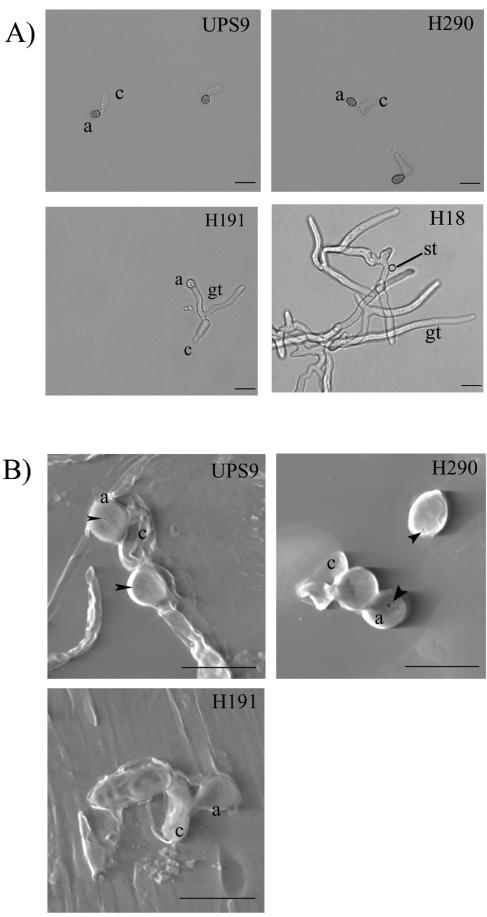

FIG. 2.

Characteristics of appressoria developed in vitro by the wild-type strain and the three nonpathogenic strains of C. lindemu-thianum. (A) Appressorium morphology in vitro 36 h after inoculation for wild-type strain UPS9 and the three penetration mutant strains. a, appressorium; c, conidium; gt, germ tube; st, swollen tip. Scale bars =25 μm. (B) Scanning electron microscopy examination of the occurrence of a penetration pore for the wild-type strain and two of the penetration mutants (H290 and H191). a, appressorium; c, conidium. Scale bars = 10 μm. Penetration pores are indicated by arrowheads. Note the flat shape of the H191 appressorium, reflecting its impaired physiological properties for generation of high internal turgor pressure.

The wild-type strain and mutant H290 formed typical, dome-shaped, melanized appressoria (Fig. 2A). By contrast, the appressoria formed by the H191 strain displayed variable but reduced melanization in vitro and in planta (Fig. 1A and 2A). Deposition of a melanin layer allows generation of high turgor pressure through the retention of accumulated solutes inside the appressorium. Appressorium turgor was measured using an incipient cytorrhysis assay, which relies on the use of hyperosmotic concentrations of a solute to collapse appressoria and thereby allows estimation of the internal turgor (11, 21). To carry out this assay, conidia were applied to a hydrophobic surface in the presence of bean medium once appressoria had developed, and they were incubated in the presence of various concentrations of glycerol. We found that 2 M glycerol was sufficient to collapse 38.5% ± 12.0% of the appressoria of wild-type strain UPS9 and 47.7% ± 5.2% of the appressoria of the H290 mutant strain, which indicated that there was no significant decrease in turgor in the appressoria of the H290 strain (Table 1). In contrast, an external glycerol concentration of 2 M resulted in the collapse of 65.8% ± 1.3% of the appressoria of the H191 strain (Table 1). This demonstrated the inability of strain H191 to generate high internal appressorial turgor pressure.

Appressoria of nonpathogenic strain H290 that differentiated in vitro showed no defect compared with appressoria of wild-type strain UPS9 in terms of the rate of differentiation, melanization, or internal turgor pressure. Therefore, in order to investigate the nature of the appressorial defect in this strain, scanning electron microscopy was utilized to examine the appressorium lower surface for the presence of the penetration pore in planta. In C. lindemuthianum, the penetration pore is the site where the penetration peg emerges to penetrate into the first plant cell (2). The frequency (85.2%) and the size of the penetration pores displayed by H290 appressoria were similar to the frequency (86.5%) and the size of the penetration pores displayed by the wild-type strain UPS9 appressoria (Fig. 2B). In accordance with the deficiencies previously characterized for the H191 appressoria, genuine penetration pores were not observed with this mutant strain.

Overall, each of the three nonpathogenic strains characterized was impaired in a distinct and different stage of C. lindemuthianum appressorium development. Strain H18 was severely impaired at the appressorium differentiation stage and exhibited typical branching and extensive growth of the germ tubes. Strain H191 was partially impaired in appressorium differentiation, but its major defect was in the appressorium maturation stage. The strain H191 appressoria differed from the appressoria developed by the H290 strain, which had wild-type morphology and properties (rate of differentiation, melanization, internal turgor pressure, and appressorial pore formation). However this strain was unable to differentiate an infection vesicle, which is the first specialized fungal cell structure inside plant tissue. We concluded, therefore, that this mutant is impaired in appressorium function.

Appressorium maturation is both necessary and sufficient for triggering most plant defense responses.

We used the three strains of C. lindemuthianum described above which are blocked at different stages of appressorium development as tools to analyze the triggering of bean defense responses during penetration of a susceptible cultivar of bean by C. lindemuthianum. For this purpose, we tested several types of defense markers that cover early as well as late plant defense responses. We tested for superoxide ion production as an early marker and for the accumulation of mRNAs of bean defense genes that are known to be transcriptionally regulated, such as the genes encoding phenylalanine-ammonia lyase (PAL3), chalcone synthase (CHS), and a cytoplasmic PR protein (PvPR2). We also examined the accumulation of secreted PR proteins in apoplastic fluids as late markers (47, 48).

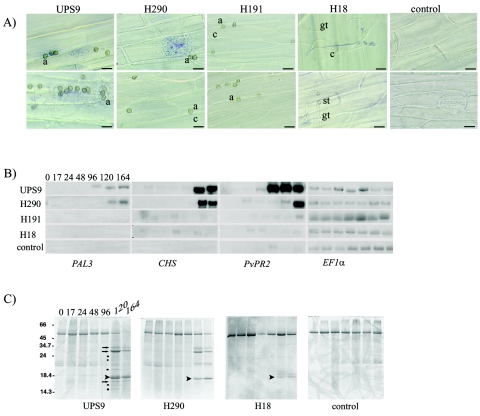

Superoxide ion (O2−) production was visualized by NBT staining in the cells directly below UPS9 appressoria at 24 and 36 h after inoculation (Fig. 3A). These times correspond to penetration and the beginning of infection vesicle differentiation, respectively. When nonpathogenic strain H290 was used, production of superoxide ions was detected in the cells below the nonfunctional appressoria 24 h after inoculation. This production was transient and disappeared by 36 h (Fig. 3A). No superoxide ion production was detected upon inoculation with either strain H191 or strain H18 (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of bean defense responses after inoculation of a susceptible cultivar of common bean (P12S) with the fully pathogenic wild-type strain UPS9 and nonpathogenic strains H18, H191, and H290 impaired in appressorium-mediated penetration. (A) Detection of superoxide ion formation. Common bean hypocotyls were inoculated, peeled 24 h (upper row) and 36 h (lower row) after inoculation, and treated as described in Materials and Methods for NBT staining. A specific blue precipitate indicates the presence of superoxide ions. For each time NBT staining was performed with two hypocotyls, each with four inoculation points. Three separate experiments were performed, and representative observations are shown. a, appressorium; c, conidium; gt, germ tube; st, swollen tip. Scale bars = 25 μm. (B) Northern blot analysis of expression of bean (P. vulgaris) phenylalanine-ammonia lyase 3 (PAL3), chalcone synthase (CHS), and pathogenesis related protein 2 (PvPR2) genes. Total RNAs were isolated from bean leaves collected immediately prior to inoculation and 17, 24, 48, 96, 120, and 164 h after inoculation. The same blots were hybridized with radiolabeled probes specific for bean constitutive elongation factor 1α (EF1α) in order to check the quality of the RNA samples and their loading. Similar results were obtained in three different time course experiments. (C) Secretion and accumulation of bean PR proteins in apoplastic fluids of bean leaves. The profile of PR protein accumulation after inoculation with the H191 strain was identical to that after inoculation with the H18 strain; only the PR protein accumulation pattern for H18 is shown. The arrowheads indicate the PR proteins that were produced after inoculation with any fungal strain, the arrows indicate the PR proteins that accumulated after inoculation with wild-type strain UPS9 and strain H290, and the asterisks indicate the PR proteins that accumulated only after inoculation with the wild-type strain. Molecular masses (in kDa) are indicated on the left.

Inoculation with wild-type strain UPS9 and mutant strain H290 elicited strong accumulation of PAL3, CHS, and PvPR2 transcripts (Fig. 3B) in bean within 96 h after inoculation. Small variations were observed in the induction time courses of these three genes after inoculation with strain H290 compared to the wild-type accumulation; no difference was observed for CHS, and delays of 24 h and 48 h were observed for PAL3 and PvPR2, respectively. No significant PAL3 transcript accumulation was detected by Northern blot analysis when the plants were either inoculated with nonpathogenic strain H191 or H18 or mock inoculated (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, faint signals were detected for PvPR2 and CHS with all strains as soon as 24 h after inoculation (Fig. 3B). The early induction of these genes may be linked to the perception of fungal conidia upon inoculation and/or conidial adhesion and growth of germ tubes on leaves.

Major secreted PR proteins were equally present after inoculation with wild-type strain UPS9 and after inoculation with strain H290 (Fig. 3C). However, one difference appeared to be late accumulation (120 h after inoculation) of many minor PR proteins that seemed to be specific for the UPS9 inoculation, because we did not observe these proteins in bean tissues inoculated with any of the three nonpathogenic strains (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that secretion and accumulation of these specific PR proteins require fungal colonization of the plant tissue. The PR protein accumulation patterns were similar after inoculation of plants with either strain H191 or strain H18. Only the protein pattern obtained with the H18 mutant strain is shown in Fig. 3C. A low-molecular-weight PR protein (Fig. 3C) was secreted and accumulated at late times, although to a lesser extent in plants inoculated with the H18 or H191 strain than in plants inoculated either with wild-type strain UPS9 or the H290 strain. Accumulation of this PR protein was not observed in mock-inoculated plants.

Overall, these results indicate that the appressorium maturation stage, which is completed in the wild-type UPS9 and H290 strains, is both necessary and sufficient for triggering most bean defense responses, including (i) early plant defense responses, such as an oxidative burst, and (ii) defense genes and accumulation of major PR proteins. Therefore, a fully functional appressorium like that found only in the wild-type strain is not necessary to trigger these responses. However, conidial adhesion and germ tube growth are also sufficient for weak induction of bean defense responses (PvPR2 and CHS induction at 24 h postinoculation) and accumulation of one PR protein.

Penetration inside the first host cell is required for avirulence recognition in the C. lindemuthianum-bean interaction.

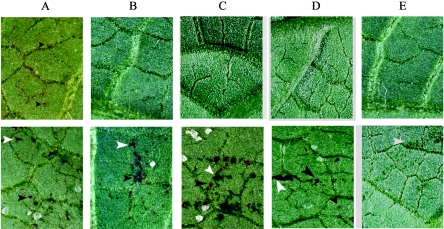

In order to determine the importance of penetration in a gene-for-gene response, we used three resistant cultivars of bean, P12R, G2333, and Michelite carrying at least three distinct resistance genes that confer resistance against strains with a UPS9 genetic background. We inoculated these three cultivars with wild-type strain UPS9, as well as with the three nonpathogenic strains which were derived from the UPS9 strain. Resistance in these three cultivars is associated with the early appearance of HR-mediated brown necrotic spots, a useful biological marker for the gene-for-gene recognition of fungal avirulence in the C. lindemuthianum-bean interaction. Figure 4 shows the results obtained following inoculation of P12R plants. Inoculation of intact P12R leaves with wild-type strain UPS9 led to HR-mediated brown necrotic spots 3 days after inoculation, which indicated that there was AvrCo2 avirulence recognition by the plant resistance gene Co-2 (Fig. 4). Accordingly, with their defects in penetration, none of the three nonpathogenic strains (H290, H191, and H18) induced the appearance of HR-mediated brown necrotic spots on intact leaves of cultivar P12R (Fig. 4). Therefore, completion of penetration associated with full appressorium function is necessary for AvrCo2 avirulence recognition by plants carrying the corresponding Co-2 resistance gene. It is known that on wounded leaves, appressorium-mediated penetration is not required in order for the fungus to enter the host cells. We utilized this artificial method of infection to confirm that the absence of avirulence recognition in the three nonpathogenic strains was due to a true physical impossibility for plant cells to detect the fungus as long as penetration had not occurred. Inoculation of P12R wounded leaves with wild-type strain UPS9 led to HR-mediated brown necrotic spots 3 days after inoculation (Fig. 4). These brown necrotic spots were similar to those observed on intact leaves, but they were clearly different from water-soaked lesions due to wounding (Fig. 4). Inoculation of P12R wounded leaves with the nonpathogenic H290, H191, and H18 strains also led to HR-mediated necrotic spots 3 days after inoculation (Fig. 4). This shows that the lack of physical contact due to a defect in penetration was responsible for the lack of avirulence recognition by plant cells. Similar results were obtained for the G2333 and Michelite cultivars (data not shown). In contrast to the triggering of bean defense responses, avirulence recognition for at least three independent gene-for-gene matching pairs in the C. lindemuthianum-common bean interaction requires true penetration of the bean epidermal cell.

FIG. 4.

Pathogenicity assays for the three penetration mutants with the common bean resistant cultivar P12R. Prior to inoculation, detached leaves were either left intact (upper row) or wounded using sand as an abrasive (lower row), which allowed the fungus to bypass appressorium-mediated penetration in order to come into contact with host cells. Leaves were inoculated with the UPS9 wild-type strain (A), H290 (B), H191 (C), and H18 (D) and were mock inoculated (E). Photographs were taken 3 days after inoculation. The black arrowheads indicate brown necrotic spots corresponding to gene-for-gene recognition that were distinct from water-soaked lesions due to wounds, which are indicated by white arrowheads.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that three nonpathogenic mutants of C. lindemuthianum are blocked at different stages of appressorium-mediated penetration of plant tissue. Our data show that there is a strict sequence during C. lindemuthianum appressorium development: appressorium differentiation, followed by appressorium maturation and then appressorium function. The H18 strain is not able to differentiate appressoria. Mutant strain H191 displays a defect in appressorium differentiation, but its nonpathogenic phenotype appears to be mainly due to a defect in appressorium maturation. H191 appressoria display a defect in pigmentation that leads to a defect in turgor pressure buildup within appressoria. This is consistent with the relationship demonstrated previously between appressorium melanization and turgor pressure buildup (11, 21). Strain H290 is able to differentiate appressoria, to generate wild-type internal turgor pressure, and to develop penetration pores, but it is unable to develop any infection structures inside the first infected host cell, such as an infection vesicle or primary hyphae. Furthermore, there is no delay in appressorium differentiation, appressorium maturation, or penetration pore formation compared to the wild-type strain. The formation of the penetration pore suggests that the penetration peg can be formed but that it is not formed sufficiently to allow entry into the host cells. Therefore, we concluded that this mutant is blocked during the appressorium function stage. This set of nonpathogenic strains is especially interesting as these strains allow detailed study of plant defense responses during the earliest stages of fungal infection.

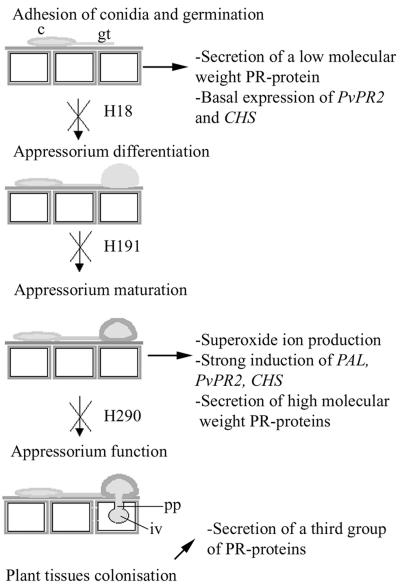

The model proposed for the triggering of bean defense responses during appressorium-mediated penetration of bean tissues by C. lindemuthianum is shown in Fig. 5. Secretion and accumulation of one low-molecular-weight PR protein in the apoplast and low-level accumulation of PvPR2 and CHS mRNA were triggered when plants were inoculated with all C. lindemuthianum strains, but not when plants were mock inoculated. This suggests that expression of these genes and secretion of the low-molecular-weight PR protein do not require appressorium development. This first weak set of plant defense responses may be due to conidial adhesion and/or germ tube growth on the host surface and may be elicited by enzymatic factors that are still produced by the germlings of the three nonpathogenic strains. They likely constitute one of the first plant defense responses after inoculation. Surprisingly, triggering of superoxide ion production, strong accumulation of PAL3, PvPR2, and CHS transcripts, and secretion of a high-molecular-weight PR protein in apoplastic fluids require appressorium maturation (melanin layer synthesis, buildup of internal turgor pressure) but not full appressorium function; i.e., they do not require the development of fungal structures inside the host cell, as strain H290 does not produce a structure such as an infection vesicle inside the first infected host cell. We show here that the degradation and/or local minor alterations of the bean cuticle and epidermal cell walls strictly localized below the penetration pore might be enough to elicit many of bean defense responses at a rate similar to the rate observed after infection with the wild-type strain. This is in agreement with the concept of endogenous elicitors, which proposes that products obtained by hydrolysis of the plant cell wall elicit plant defense responses even at low concentrations (17, 26). Furthermore, products of the oxidative burst, such as H2O2, may act as second messengers (6) and can trigger bean defense responses, as they were observed in bean tissues inoculated with the wild-type strain and strain H290. Recently, Park and coworkers suggested that the induction of expression of two defense-related genes, PR1 and PBZ1 in rice, is not triggered by penetration peg formation (35). Our study is in agreement with this. We speculate that a common mechanism for sensing the fungus at the surface of the plant is conserved in rice (a monocotyledonous plant) and bean (a dicotyledonous plant).

FIG. 5.

Model for development at the penetration step and triggered plant defense events in the interaction between C. lindemuthianum and common bean (P. vulgaris). c, conidium; gt, germ tube; iv, infection vesicle; pp, penetration peg.

In contrast to the triggering of ion superoxide production, induction of the expression of bean defense genes, and PR protein secretion, we showed that recognition of at least three of the putative avirulence factors by matching resistant bean cultivars requires genuine penetration and development of internal infection structures, such as infection vesicles and primary hyphae. Our results suggest that these avirulence factors are produced when plant penetration occurs and may be triggered by extracellular compounds secreted by the fungus or fungal cell wall proteins. The data obtained in this study by using penetration mutants are in agreement with the data for the in planta development of C. lindemuthianum and the findings of O'Connell and Bailey which showed that resistance is expressed at different stages of infection (32). Tissue wounding allows avirulence factor recognition for all the mutant strains, but we do not know which type of artificial contact occurs in wounded tissues. However, our results suggest that the production of the virulence factors could be not under control of the genetic program required for penetration and can be decoupled from the appressorium morphogenesis program. This could lead to a research trail for the isolation of avirulence factors of C. lindemuthianum.

In addition to having a defect in appressorium differentiation, mutant strains H18 and H191 produced long, branching germ tubes. These results strongly suggest that there is a correlation between germ tube length and defective appressorium differentiation. As reported previously, the H290 mutant produces nonexpanding lesions (15), and the H191 strain does not form lesions on wounded leaves (34). We show here that mutant strain H18 is also unable to colonize plant tissues and to cause anthracnose symptoms when it is inoculated onto wounded plant surfaces. These data and data for other Colletotrichum species (25, 42, 43, 53) suggest that in Colletotrichum species appressorium differentiation and maturation are compulsory developmental steps before colonization and degradation of host tissues. Consequently, if these steps do not take place, colonization does not occur even if the plant tissue surface is already mechanically broken. This hypothesis is in agreement with the results of previous experiments in which C. lindemuthianum mycelium was placed on mechanically wounded bean hypocotyls and could not invade the host (3). A fully mature appressorium is a terminally differentiated cell type, and its complete maturation may be viewed as “a point of no return.” When an appressorium is completely formed and mature, it cannot return to the vegetative mycelium state. This is what we observed for mutant strain H290 in appressorium differentiation experiments on glass or plastic surfaces, but not for mutant strains H191 and H18, which formed long germ tubes and finally mycelia. In this respect, it has been suggested that appressoria have a crucial role in the reorientation of fungal growth in order to position and attach the fungus to the host surface and serve as a signal to develop the cellular tools necessary for penetration of the host (10, 16).

Acknowledgments

We thank Denise Parisot and Anne-Laure Pellier for helpful discussions, Roland Boyer for the photographs, and Odile Roche for her helpful advice concerning microscopy.

This work was supported by the Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique, the Université Paris-Sud, and the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique and by a grant to C. Veneault-Fourrey from the French Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrios, G. N. 1997. Plant pathology, 4th ed. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 2.Bailey, J. A., and M. J. Jeger. 1992. Colletotrichum: biology, pathology and control, p. 94. CAB International, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 3.Bailey, J. A., and M. J. Jeger. 1992. Colletotrichum: biology, pathology and control. CAB International, Oxon, United Kingdom.

- 4.Bailey, J. A., P. M. Rowell, and G. M. Arnold. 1980. The temporal relationship between host cell death, phytoalexin accumulation and fungal inhibition during hypersensitive reactions of Phaseolus vulgaris to Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 17:329-339. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechinger, C., K.-F. Giebel, M. Schnell, P. Leiderer, H. B. Deising, and M. Bastmeyer. 1999. Optical measurements of invasive forces exerted by appressoria of a plant pathogenic fungus. Science 285:1896-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolwell, G. P., and P. Wojtaszek. 1997. Mechanisms for the generation of reactive oxygen species in plant defence—a broad perspective. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 51:347-366. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourett, T. M., and R. J. Howard. 1992. Actin in penetration pegs of the fungal rice blast pathogen, Magnaporthe grisea. Protoplasma 168:20-26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chumley, F. G., and B. Valent. 1990. Genetic analysis of melanin-deficient, nonpathogenic mutants of Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 3:135-143. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean, R. A. 1997. Signal pathways and appressorium morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 35:211-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deising, H. B., S. Werner, and M. Wernitz. 2000. The role of fungal appressoria in plant infection. Microbes Infect. 2:1631-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong, J. C., B. J. McCormack, N. Smirnoff, and N. J. Talbot. 1997. Glycerol generates turgor in rice blast. Nature 398:244-245. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Wit, P. J. G. M. 1997. Pathogen avirulence and plant resistance: a key role for recognition. Trends Plant Sci. 2:452-458. [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Wit, P. J. G. M., and G. Spikman. 1982. Evidence for the occurrence of race- and cultivar-specific elicitors of necrosis in intercellular fluids of compatible interactions of Cladosporium fulvum and tomato. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 21:1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon, R. A., and C. Lamb. 1990. Molecular communication in interactions between plants and microbial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 41:339-367. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dufresne, M., J. A. Bailey, M. Dron, and T. Langin. 1998. clk1, a serine/threonine protein kinase-encoding gene, is involved in pathogenicity of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum on common bean. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emmett, R. W., and D. G. Parbery. 1975. Appressoria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 13:147-167. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esquerré-Tugayé, M.-T., G. Boudart, and B. Dumas. 2000. Cell wall degrading enzymes, inhibitory proteins, and oligosaccharides participate in the molecular dialogue betweeen plants and pathogens. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38:157-163. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flor, H. H. 1971. Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9:275-296. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geffroy, V., F. Creusot, J. Falquet, M. Sévignac, A.-F. Adam-Blondon, H. Bannerot, P. Gepts, and M. Dron. 1998. A family of LRR sequences in the vicinity of the Co-2 locus for anthracnose resistance in Phaseolus vulgaris and its potential use in marker-assisted selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96:494-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gus-Mayer, S., B. Naton, K. Hahlbrock, and E. Schmelzer. 1998. Local mechanical stimulation induces components of the pathogen defense response in parsley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8398-8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard, R. J., M. A. Ferrari, D. H. Roach, and N. P. Money. 1991. Penetration of hard substrates by a fungus employing enormous turgor pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:11281-11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang, C.-S., M. A. Flaishman, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1995. Cloning of a gene expressed during appressorium formation by Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes and a marked decrease in virulence by disruption of this gene. Plant Cell 7:183-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, Y.-K., T. Kawano, D. Li, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 2000. A mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase required for induction of cytokinesis and appressorium formation by host signals in the conidia of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Plant Cell 12:1331-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, Y.-K., D. Li, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1998. Induction of Ca2+-calmodulin signaling by hard-surface contact primes Colletotrichum gloeosporioides conidia to germinate and form appressoria. J. Bacteriol. 180:5144-5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, Y.-K., Z.-M. Liu, D. Li, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 2000. Two novel genes induced by hard-surface contact of Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes conidia. J. Bacteriol. 182:4688-4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klarzynski, O., B. Plesse, J. M. Joubert, J. C. Yvin, M. Kopp, B. Kloareg, and B. Fritig. 2000. Linear beta-1,3 glucans are elicitors of defense responses in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 124:1027-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolattukudy, P. E., L. M. Rogers, D. Li, C.-S. Hwang, and M. A. Flaishman. 1995. Surface signaling in pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4080-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langfelder, K., M. Streibel, B. Jahn, G. Haase, and A. A. Brakhage. 2003. Biosynthesis of fungal melanins and their importance for human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 38:143-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, N., C. A. D'Souza, and J. W. Kronstad. 2003. Of smuts, blasts, mildews, and blights: cAMP signaling in phytopathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 41:399-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, Z.-M., and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1999. Early expression of the calmodulin gene, which precedes appressorium formation in Magnaporthe grisea, is inhibited by self-inhibitors and requires surface attachment. J. Bacteriol. 181:3571-3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendgen, K., M. Hahn, and H. Deising. 1996. Morphogenesis and mechanisms of penetration by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34:367-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connell, R. J., and A. Bailey. 1988. Differences in the extent of fungal development, host cell necrosis and symptom expression during race-cultivar interactions between Phaseolus vulgaris and Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Plant Pathol. 37:351-362. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osbourn, A. E. 1999. Antimicrobial phytoprotectants and fungal pathogens: a commentary. Fungal Genet Biol. 26:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisot, D., M. Dufresne, C. Veneault, R. Laugé, and T. Langin. 2002. CLAP1, a gene encoding a copper-transporting ATPase involved in the infection process of the phytopathogenic fungus Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:139-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park, G., K. S. Bruno, C. J. Staiger, N. J. Talbot, and J.-R. Xu. 2004. Independent genetic mechanisms mediate turgor generation and penetration peg formation during plant infection in the rice blast fungus. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1695-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pastor-Corales, M. A., O. A. Erazo, E. I. Estrada, and S. P. Singh. 1994. Inheritance of anthracnose resistance in common bean accession G 2333. Plant Dis. 78:959-962. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perfect, S. E., H. B. Hughes, R. J. O'Connell, and J. R. Green. 1999. Colletotrichum: a model genus for studies on pathology and fungal-plant interactions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27:186-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perpetua, N. S., Y. Kubo, N. Yasuda, Y. Takano, and I. Furusawa. 1996. Cloning and characterization of a melanin biosynthetic THR1 reductase gene essential for appressorial penetration of Colletotrichum lagenarium. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 9:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Schulze-Lefert, P. 2004. Knocking on the heaven's wall: pathogenesis of and resistance to biotrophic fungi at the cell wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7:377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Somssich, I. E., and K. Hahlbrock. 1998. Pathogen defence in plants—a paradigm of biological complexity. Trends Plant Sci. 3:86-90. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takano, Y., T. Kikuchi, Y. Kubo, J. E. Hamer, K. Mise, and I. Furusawa. 2000. The Colletotrichum lagenarium MAP kinase gene CMK1 regulates diverse aspects of fungal pathogenesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:374-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takano, Y., K. Komeda, K. Kojima, and T. Okuno. 2001. Proper regulation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase is required for growth, conidiation, and appressorium function in the anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum lagenarium. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:1149-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takano, Y., E. Oshiro, and T. Okuno. 2001. Microtubule dynamics during infection-related morphogenesis of Colletotrichum lagenarium. Fungal Genet. Biol. 34:107-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thines, E., R. W. Weber, and N. J. Talbot. 2000. MAP kinase and protein kinase A-dependent mobilization of triacylglycerol and glycogen during appressorium turgor generation by Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell 12:1703-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tucker, S. L., and N. J. Talbot. 2001. Surface attachment and pre-penetration stage development by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39:385-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Loon, L. C., W. S. Pierpoint, T. Boller, and V. Conejero. 1994. Recommendations for naming plant pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 3:245-264. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Loon, L. C., and E. A. Van Strien. 1999. The families of pathogenesis-related proteins, their activities, and comparative analysis of PR-1 type proteins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 55:85-97. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viaud, M. C., P. V. Balhadère, and N. J. Talbot. 2002. A Magnaporthe grisea cyclophilin acts as a virulence determinant during plant infection. Plant Cell 14:917-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu, J.-R. 2000. MAP kinases in fungal pathogens. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31:137-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu, J.-R., C. J. Staiger, and J. E. Hamer. 1998. Inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mps1 from the rice blast fungus prevents penetration of host cells but allows activation of plant defense responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12713-12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu, J.-R., M. Urban, J. A. Sweigard, and J. E. Hamer. 1997. The CPKA gene of Magnaporthe grisea is essential for appressorial penetration. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:187-194. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, Z., and M. B. Dickman. 1999. Colletotrichum trifolii mutants disrupted in the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase are nonpathogenic. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:430-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]