Abstract

CYP51 exists in all organisms that synthesize sterols de novo. Plant CYP51 encodes an obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase involved in the postsqualene sterol biosynthetic pathway. According to the current gene annotation, the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome contains two putative CYP51 genes, CYP51A1 and CYP51A2. Our studies revealed that CYP51A1 should be considered an expressed pseudogene. To study the functional importance of the CYP51A2 gene in plant growth and development, we isolated T-DNA knockout alleles for CYP51A2. Loss-of-function mutants for CYP51A2 showed multiple defects, such as stunted hypocotyls, short roots, reduced cell elongation, and seedling lethality. In contrast to other sterol mutants, such as fk/hydra2 and hydra1, the cyp51A2 mutant has only minor defects in early embryogenesis. Measurements of endogenous sterol levels in the cyp51A2 mutant revealed that it accumulates obtusifoliol, the substrate of CYP51, and a high proportion of 14α-methyl-Δ8-sterols, at the expense of campesterol and sitosterol. The cyp51A2 mutants have defects in membrane integrity and hypocotyl elongation. The defect in hypocotyl elongation was not rescued by the exogenous application of brassinolide, although the brassinosteroid-signaling cascade is apparently not affected in the mutants. Developmental defects in the cyp51A2 mutant were completely rescued by the ectopic expression of CYP51A2. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the Arabidopsis CYP51A2 gene encodes a functional obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase enzyme and plays an essential role in controlling plant growth and development by a sterol-specific pathway.

Sterols are ubiquitous among most eukaryotic organisms. Bulk sterols, such as cholesterol in animals, ergosterol in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and sitosterol in plants, serve to regulate membrane fluidity and permeability and indirectly affect the activity and distribution of integral membrane proteins, including enzymes, ion channels, and signal transduction components (Hartmann, 1998). These sterols also serve as precursors for bioactive molecules, such as mammalian steroid hormones, plant brassinosteroid (BR) hormones, and insect ecdysteroids to control developmental processes (Clouse, 2000). BRs are plant hormones that have important roles in plant development, including cell elongation, division, vascular differentiation, senescence, and stress responses (Clouse and Sasse, 1998). Plant sterols are also substrates for the synthesis of a wide range of secondary metabolites (Hartmann, 1998). Recently, the implication of sitosterol glucoside in the synthesis of cellodextrins has been proposed (Peng et al., 2002), and a link between sterol biosynthesis and cellulose production has been further documented (Schrick et al., 2004a).

Plant sterols derive from cycloartenol via a series of reactions, including methylation, reduction, isomerization, and desaturation. The molecular genetic and biochemical analyses using Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants for genes encoding sterol biosynthetic enzymes have provided new insights into the essential roles of sterols in embryogenesis, cell division and expansion, vascular patterning, and hormone signaling (Clouse, 2002; Schaller, 2003). So far, a number of sterol biosynthetic mutants have been isolated—smt1/orc/cph (sterol methyltransferase 1; Diener et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2002; Willemsen et al., 2003), fk/hydra2 (sterol C-14 reductase; Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000; Souter et al., 2002), hydra1 (Δ8-Δ7-sterol isomerase; Schrick et al., 2002; Souter et al., 2002), cvp1 (sterol methyltransferase 2; Carland et al., 2002), ste1/dwf7 (Δ7-sterol C-5 desaturase; Choe et al., 1999b; Husselstein et al., 1999), dwf5 (sterol Δ7-reductase; Choe et al., 2000), and dim/dwf1/cbb1 (sterol C-24 reductase; Kauschmann et al., 1996; Klahre et al., 1998; Choe et al., 1999a). Schaeffer et al. (2001) described plants showing cosuppression and overexpression of SMT2, which mediates an immediate next step of HYDRA1. SMT2 was shown to be a modulator that determines the ratio of 24-ethylsterol to 24-methylsterol and then controls plant growth and development (Schaeffer et al., 2001). Based on the results using these mutants and transgenic plants, the sterol biosynthetic pathway can be divided into two pathways in terms of embryogenesis and vascular patterning, that is, sterol-dependent (BR-independent) and BR-dependent pathways. According to Clouse (2002), branch points for the two pathways are the sterol intermediate 24-methylenelophenol and the SMT2/SMT3 enzymes. The mutants upstream of 24-methylenelophenol show defects in embryogenesis and a unique vascular patterning, but downstream mutants do not. The cvp1/smt2 mutant shows composite phenotypes, that is, unique vascular patterning as in smt1/orc, fk/hydra2, and hydra1, but no altered embryogenesis as in downstream mutants such as ste1/dwf7, dwf5, and dwf1/dim/cbb1. This indicates that the cellular level of sterol intermediates around 24-methylenelophenol might serve as a key factor controlling sterol-dependent embryogenesis and vascular differentiation.

Recent studies in animal systems revealed that cholesterol and its derivatives play essential roles as signaling molecules to control various developmental processes, including embryonic development (Edwards and Ericsson, 1999; Debeljak et al., 2003). For example, hedgehog proteins are processed by proteolytic cleavage and then modified by the direct covalent attachment of cholesterol to the N-terminal peptide. This sterol-protein ligand then binds to a cell surface receptor to activate a signaling pathway essential for embryogenesis. In plant systems, phytosterols are also believed to act as signaling molecules to regulate diverse plant developmental processes (Clouse, 2002). The sterol-lipid binding (Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Transfer [StART]) domain has been found in a number of signaling proteins, including homeodomain proteins (Kallen et al., 1998; Ponting and Aravind, 1999). In plant systems, the StART domain was found in the homeodomain HD-ZIP family of putative transcription factors such as PHABULOSA (ATHB14) and GLABRA2, which are involved in leaf morphogenesis and trichome and root hair development, respectively (Ponting and Aravind, 1999; Schrick et al., 2004b). Recently, He et al. (2003) showed that the expression of genes involved in cell expansion and cell division are modulated in Arabidopsis seedlings treated with sterol biosynthesis inhibitors, indicating regulatory functions of pathway end products found in a wild-type sterol profile in plant development.

Several cytochrome P450s are involved in sterol and BR biosynthetic and catabolic pathways. The CYP51 gene is thought to be one of the most ancient and conserved P450s across the kingdoms. CYP51 is essential for sterol biosynthesis, and it is the only orthologous P450 family that can be recognized in the bacterial, fungal, mammal, and plant kingdoms (Yoshida et al., 1997; Debeljak et al., 2003). Plant CYP51 encodes obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase involved in the postsqualene segment of the sterol biosynthetic pathway. In the biosynthesis of sterols in eukaryotes, the removal of the 14α-methyl group mediated by CYP51 provides a most important structural feature of sterol molecules. CYP51 genes have been isolated from several plant species since the first isolation of a CYP51 gene from sorghum (Bak et al., 1997). Null mutants for plant CYP51 genes have not been described to date, although a suppression mutant for Arabidopsis CYP51A2 obtained by an antisense approach was reported (Kushiro et al., 2001). Virus-induced silencing using CYP51 from Nicotiana tabacum resulted in the accumulation of obtusifoliol, the substrate of CYP51, and other 14α-methyl sterols, with a concomitant growth reduction phenotype in Nicotiana benthamiana (Burger et al., 2003).

The Arabidopsis genome contains two CYP51 genes, CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 (according to some authors [Nelson et al., 2004], CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 have other names, CYP51G2 and CYP51G1, respectively). We show here through sequence analysis and molecular complementation that CYP51A1 is an expressed pseudogene. To clearly understand the function of the CYP51A2 gene in plant growth and development, we have isolated loss-of-function mutants from T-DNA-tagging mutant pools by systematic reverse genetics methods and characterized their morphological and biochemical phenotypes. The loss-of-function mutant for CYP51A2 showed a novel type of seedling-lethal phenotype not corrected by exogenous BR application, and accumulated obtusifoliol, the substrate of CYP51. Our results suggest that CYP51A2 encodes the only functional obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase and plays a critical role in plant growth and development by a sterol-specific pathway in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

Two CYP51 Genes in Arabidopsis

The Arabidopsis genome sequence has revealed two putative CYP51 genes: CYP51A1 (At2g17330) on chromosome 2, with a modified heme-binding region consensus sequence (LxxGxRxCxG), and CYP51A2 (At1g11680) on chromosome 1, with a conserved heme-binding region consensus sequence (FxxGxRxCxG). According to the current Arabidopsis gene annotations, CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 genes encode proteins of 473- and 488-amino acid residues, respectively (http://www.arabidopsis.org; http://www.p450.kvl.dk). A full-length cDNA clone was isolated only for CYP51A2 (GenBank accession nos. AY050860 and AB014459; Kushiro et al., 2001). The annotated CYP51A1 protein is atypically shorter than the CYP51A2 protein as well as other plant CYP51 proteins. Therefore, to check the annotation of the CYP51A1 gene, we obtained a full-length cDNA for CYP51A1 from seedling mRNA of ecotype Columbia (Col-0), and its sequence (GenBank accession no. AY666123) was aligned with CYP51A2 cDNA and CYP51A1 genomic sequences. This analysis revealed that the intron boundaries in the two sequences are identical and that the nucleotide (guanine) corresponding to nucleotide 435 of the CYP51A2 reading frame was missing in CYP51A1. This led to a premature stop codon in exon 1 and a maximal reading frame of 145 amino acids (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR revealed that the CYP51A1 transcript is expressed specifically in roots, and our results indicate that CYP51A1 might be an expressed pseudogene (data not shown).

A single intron was identified in the CYP51A1 gene, while CYP51A2 contains two, one in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and the other in the coding region. The intron in the 5′-UTR was identified by sequence alignment of a genomic sequence with the full-length cDNA for CYP51A2 and confirmed by RT-PCR (data not shown). The introns contain the canonical splice junctions, that is, GT at the 5′- and AG at the 3′-end.

Isolation of CYP51 Mutant Alleles

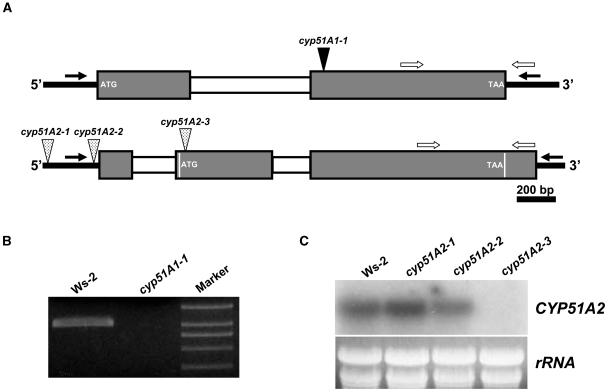

As the first step toward the elucidation of the biological roles of the CYP51 genes in plant growth and development, T-DNA knockout lines were isolated by a PCR-based reverse genetics approach. Figure 1A shows that PCR screening of DNA representing 120,000 insertions resulted in one allele for cyp51A1 (cyp51A1-1) and three alleles for cyp51A2 (cyp51A2-1 to 3).The T-DNA insertion sites were found at 686 and 383 bp upstream of the ATG start codon for cyp51A2-1 and cyp51A2-2, respectively. To check gene expression in the mutant alleles, RT-PCR and RNA gel-blot analysis were performed using total RNA from wild-type and mutant alleles (Fig. 1, B and C). RT-PCR was done to detect transcripts in wild type and cyp51A1-1 due to a low expression level of the CYP51A1 gene in wild type. CYP51A1 transcripts were not detected in the cyp51A1-1 mutant (Fig. 1B). RNA gel-blot analysis also showed that the cyp51A2-3 allele is a null mutant (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the gene expression level was reduced or not changed in cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-1 alleles, respectively, compared to wild type (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that less than 700 bp is sufficient as a promoter for the CYP51A2 gene under normal growth conditions.

Figure 1.

Isolation of loss-of-function mutants for CYP51A1 and CYP51A2. A, Schematic representation of T-DNA insertions in CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 genes. Mutant lines were isolated by PCR-based reverse genetics using a gene-specific primer and a T-DNA border primer on DNA from lines containing 120,000 T-DNA insertions. Gray and white boxes indicate exons and introns, respectively. The second exon of the CYP51A2 gene contains 10 bp between the 5′-UTR intron and the ATG start codon. The size of the first exon of 5′-UTR of CYP51A2 gene is based on a full-length cDNA clone (AY050860). Black and white arrows indicate gene-specific primers to isolate T-DNA insertion mutants and primers for RT-PCR, respectively. B, RT-PCR analysis to confirm knockout mutation in the cyp51A1 mutant. Total RNA was isolated from 10-d-old seedlings of wild-type and cyp51A1 mutants. C, RNA gel-blot analysis to confirm knockout and/or knockdown mutations in the cyp51A2 mutants. Total RNA was isolated from 10-d-old seedlings of wild-type and cyp51A2 mutants.

The cyp51A1 mutant allele did not show any noticeable morphological changes compared to wild-type Wassilewskija (Ws)-2 at seedling and rosette stages (data not shown), while a mutation in the CYP51A2 gene resulted in seedling lethality (Fig. 2). We performed genetic complementation by crossing homozygous transgenic plants ectopically expressing CYP51A1 and a heterozygous cyp51A2-3 allele. The constitutive expression of the CYP51A1 gene in a cyp51A2-3 homozygous plant failed to correct seedling lethality (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Taken together with the sequence analysis, this result further supports the conclusion that CYP51A1 is an expressed pseudogene. Therefore, in this article we have focused on analyzing the functional roles of the CYP51A2 gene.

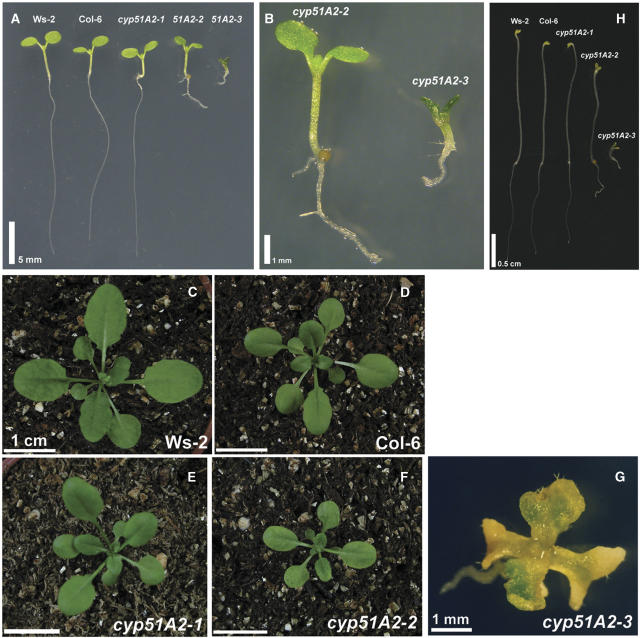

Figure 2.

Morphology of cyp51A2 mutants at seedling and rosette stages. A, Seven-day-old light-grown seedlings. B, Detailed view of cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3 mutants in A. C to F, Twenty-day-old wild types, cyp51A2-1, and cyp51A2-2 mutants grown on soil. G, Twenty-day-old cyp51A2-3 mutant grown on Murashige and Skoog medium. H, Morphology of etiolated seedlings. Seeds were germinated on 1% agar-solidified Murashige and Skoog medium in dark conditions for 4 d. The etiolated seedlings were aligned for photography. Bar = 5 mm (A); bar = 1 cm (C–F); bar = 1 mm (B and G); bar = 0.5 cm (H).

Crosses of either cyp51A2-2 or cyp51A2-3 to wild-type Ws-2 showed that two of the mutant alleles, cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3, were segregated as monogenic, recessive Mendelian traits. The frequencies of mutant phenotypes in F2 progenies were slightly lower than the expected values of homozygous plants for cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3 mutations in the crosses: 22.6% [for cyp51A2-2, x2 value = 0.811 (P > 0.1)] and 21.5% (for cyp51A2-3, x2 value = 2.137 (P > 0.1)], respectively.

The Loss-of-Function Mutation for CYP51A2 Resulted in Seedling Lethality

Figure 2 illustrates the morphology of cyp51A2 mutant seedlings at 5 d of age and rosettes at 20 d of age under light conditions. The phenotypic changes in cyp51A2 mutant alleles were in proportion to the gene expression level among the mutant alleles. At both stages, the cyp51A2-1 allele, in which the gene expression level was comparable to wild type, did not show any noticeable morphological changes compared to its corresponding wild-type Col-6 (Fig. 2, A, D, and E). In contrast, cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3 alleles have prominent phenotypes. At the seedling stage, root development and cotyledonary petiole elongation were inhibited in both cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3 alleles, although the defects in the cyp51A2-3 allele were more severe than in the cyp51A2-2 allele (Fig. 2, A and B). Hypocotyl elongation was greatly reduced in the cyp51A2-3 allele, but hypocotyl elongation in the cyp51A2-2 allele was similar to wild-type Ws-2 (Fig. 2, A and B).

The cyp51A2-2 allele exhibited retarded plant growth at the 20-d-old rosette stage compared to wild type (Fig. 2, C and F). In contrast, the cyp51A2-3 allele produced only two to four deformed true leaves that were yellow or pale green (Fig. 2G) and finally resulted in seedling lethality.

Dark-grown wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings have greatly elongated hypocotyls, unopened cotyledons, and an apical hook. BR or phytosterol-deficient mutants usually show photomorphogenic development in the dark (i.e. the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation, the lack of apical hook, and the opening of cotyledons; Kauschmann et al., 1996; Szekeres et al., 1996). We checked whether dark development is affected in the cyp51A2 mutants. Similar to light-grown plants (Fig. 2A), the cyp51A2-1 mutant showed normal development in the dark (Fig. 2H). However, cyp51A2-2 and cyp51A2-3 alleles showed developmental changes in proportion to endogenous gene expression levels (Fig. 1C). Hypocotyl and root elongation was inhibited in the two alleles compared to wild type (Fig. 2H). The inhibition was more severe in cyp51A2-3 than in cyp51A2-2. The cotyledons also opened in the two mutant alleles, mimicking photomorphogenic development in the dark condition.

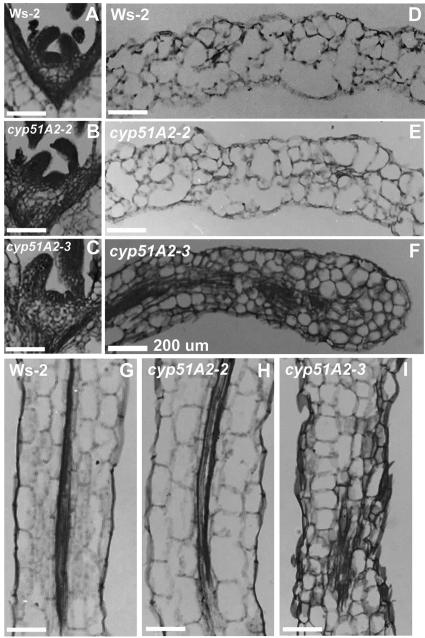

Figure 3 shows the microscopic analyses of the shoot apical meristem (SAM), cotyledon, and hypocotyl tissues in cyp51A2 mutants. SAMs of wild-type and cyp51A2-2 alleles were densely stained with toluidine blue (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, the SAM of the cyp51A2-3 allele was stained weakly, but the size and shape is comparable to wild type (Fig. 3C). The cell length of cotyledon and hypocotyl in cyp51A2-3 was reduced by one-half compared to wild-type and cyp51A2-2 alleles (Fig. 3, D–I). The cell shape and size were irregular in the cyp51A2-3 allele (Fig. 3, F and I). These results indicate that the defects in cotyledon and hypocotyl are caused by improper cellular elongation in the cyp51A2 mutant.

Figure 3.

Light microscopy of cyp51A2 mutant seedlings. All tissues were prepared from 5-d-old plants. A, D, and G, SAM, cotyledon, and hypocotyl of wild-type Ws-2, respectively. B, E, and H, SAM, cotyledon, and hypocotyl of cyp51A2-2, respectively. C, F, and I, SAM, cotyledon, and hypocotyl of cyp51A2-3, respectively. Bars = 200 μm.

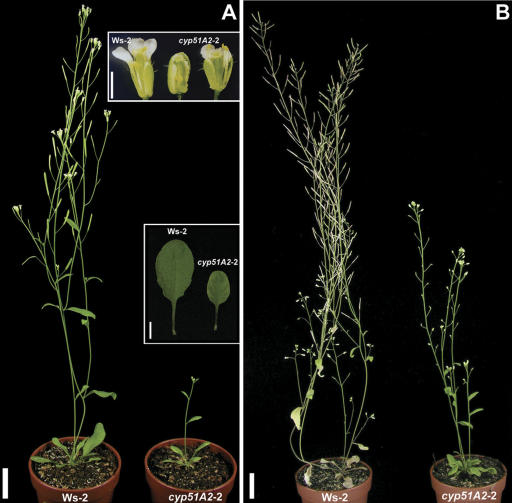

Figure 4 illustrates the morphology of mature cyp51A2-2 plants grown under light conditions. In contrast, the cyp51A2-3 mutant died at the seedling stage. To understand the role of phytosterols in plant growth and development, we analyzed the phenotype of the cyp51A2-2 allele through seed fill and senescence. The cyp51A2-2 mutant showed several morphological changes compared to the wild-type plant. Leaf size was reduced and yellow or pale green at the leaf margin, although the leaf shape was normal when compared to wild type (Fig. 4A, inset). The mutant had normal floral structures, but flowers were often not opened in the mutant (Fig. 4A, inset). The stamen of the unopened flower was often not fully elongated, which resulted in a sterile plant (Fig. 4A, inset, and B). Fruit elongation did not occur in the mutant, probably due to the failure of pollination and/or fertilization or a defect in the elongation of the carpel itself. Petal margin of the mutant was often serrated, whereas that of the wild type is smooth (Fig. 4A, inset). This petal characteristic was also observed in the transgenic Arabidopsis cosuppressing SMT2 (Schaeffer et al., 2001), smt1 (Willemsen et al., 2003), and cvp1 (Carland et al., 2002). At 7 weeks of age, wild-type plants became senescent at the whole-plant level and dispersed seeds. In contrast, cyp51A2-2 plants remained green and still flowering at this age, indicating that the growth rate was retarded in the mutant (Fig. 4B). This slow growth rate was also observed in transgenic Arabidopsis plants in which CYP51A2 gene expression was suppressed by an antisense construct using Arabidopsis CYP51A2 (Kushiro et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

Morphology of mature cyp51A2-2 mutants. A, Plant morphology at 4 weeks of age. B, Plant morphology at 7 weeks of age. cyp51A2-2 mutants showed delayed plant growth compared to wild type. Bar = 2 cm (A and B). Bar = 0.5 cm for leaves and 1 mm for flowers (A, insets).

Early Embryogenesis Is Normal in cyp51A2-3 Mutants

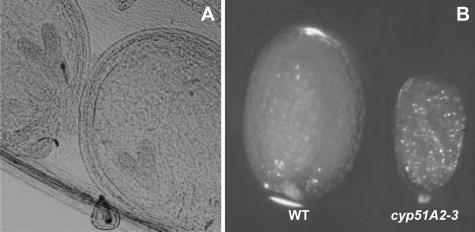

Sterols play essential roles during plant embryogenesis (Clouse, 2000). The sterol-specific biosynthetic mutants, such as smt1, fk/hydra2, and hydra1, are defective in embryogenesis (Diener et al., 2000; Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000). The siliques from heterozygous plants containing the cyp51A2-3 mutation were cleared and opened to observe late-heart-stage embryos under the light microscope (Fig. 5A). All of the embryos at their late heart stage were very similar to those of wild type, indicating that cyp51A2-3 was not affected in the early embryogenesis phase. However, later steps in the development of homozygous cyp51A2-3 seeds were affected because the seeds were small and shriveled when compared to heterozygous or wild-type seeds (Fig. 5B). The shriveled seeds contained smaller embryos compared to those of wild type (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Early embryogenesis in cyp51A2-3 mutants. A, Embryos at late heart stage from heterozygous plants of cyp51A2-3. No embryos in siliques show noticeable developmental defects at this stage. B, Morphology of mature seeds. Notice the small and shriveled seeds homozygous for the cyp51A2-3 mutation.

Responses to BR and Phytosterols, and Membrane Integrity in cyp51A2 Mutants

The dwarf stature and reduced hypocotyl elongation in sterol and BR biosynthetic mutants can be rescued by exogenous application of BRs and/or BR intermediates (Szekeres et al., 1996; Klahre et al., 1998). In order to see whether cyp51A2 mutant phenotypes are corrected by exogenous brassinolide (BL) treatment, 5-d-old light-grown seedlings were treated with 0.1 μm of epi-BL under light conditions for 5 d. Wild-type seedlings showed a 55% increase in their hypocotyl length. However, we did not observe noticeable rescue in the phenotypes of cyp51A2-2 and -3 mutants, although cotyledon petioles were often curled downward (data not shown), as previously observed in fk mutants (Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000). To determine whether the exogenous application of sterols can rescue the defects in cyp51A2-3, the mutant seedlings were grown in a mixture of campesterol and sitosterol at various concentrations between 50 and 200 μm. In no case was any evidence of phenotypic rescue observed (data not shown), as also reported for fk mutants (Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000).

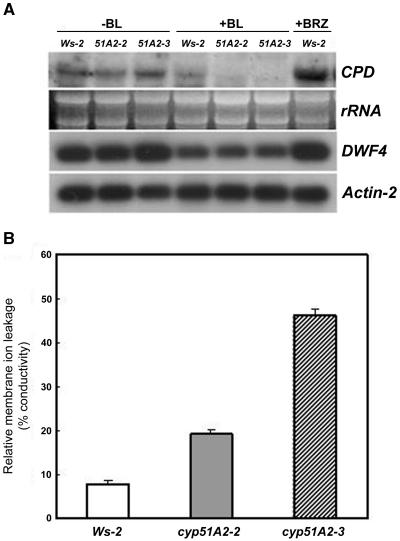

BR biosynthesis has been known to be tightly controlled by feedback regulation through the BR-signaling cascade. DWF4 and CPD gene expression levels were increased in their corresponding mutants and down-regulated by exogenous BR application (Bishop and Koncz, 2002). Exogenous BR application does not rescue the reduced hypocotyl elongation in sterol mutants upstream of smt2, indicating sterol-specific roles in the control of cell elongation. To determine whether BR signaling is aberrant in cyp51A2, we checked DWF4 and CPD expression levels in this mutant. DWF4 and CPD transcript levels were up-regulated in the cyp51A2-3 allele compared to wild type and to cyp51A2-2, while exogenous BR application suppressed DWF4 and CPD levels in cyp51A2-3 as much as in wild type and cyp51A2-2 (Fig. 6A), indicating that BR signaling in cyp51A2 might be normal. The BR inhibitor, BRZ, induced DWF4 and CPD expression levels, thus mimicking the BR biosynthetic mutant (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that the lack of rescue of cell elongation in the cyp51A2 mutant by exogenous BR application is not due to aberrant BR signaling.

Figure 6.

Expression level of BR biosynthetic genes in cyp51A2 mutants with and without exogenous BR (A) and membrane ion leakage (B) in cyp51A2 mutants. A, Expression level of BR biosynthetic genes, CPD and DWF4, in cyp51A2-3 mutants was changed as much as in wild type by the treatments with or without BR. Total RNAs were isolated from 7-d-old light-grown seedlings treated with or without epi-BL (0.5 μm) and a BR biosynthesis inhibitor, BRZ (1 μm), for 2 d. Total RNAs were subject to northern hybridization (CPD) and RT-PCR (DWF4). Actin-2 was used as a positive control. B, Membrane ion leakage was determined by measuring electrolytes leaked using 10-d-old wild-type (Ws-2), cyp51A2-2, and cyp51A2-3 mutant seedlings.

Sterols are essential components in maintaining membrane fluidity and permeability in living cells. Living organisms regulate membrane fluidity and permeability by modulating sterol content to adapt to changing environments (Hartmann, 1998). We hypothesized that membrane integrity would be changed in the cyp51A2 mutants, in which many morphological changes were observed. We therefore measured ion leakage in the mutants as an index for membrane integrity. Membrane ion leakage as described in percentage conductivity was proportional to phenotype severity (Fig. 6B), indicating that membrane integrity was affected in the cyp51A2 mutants.

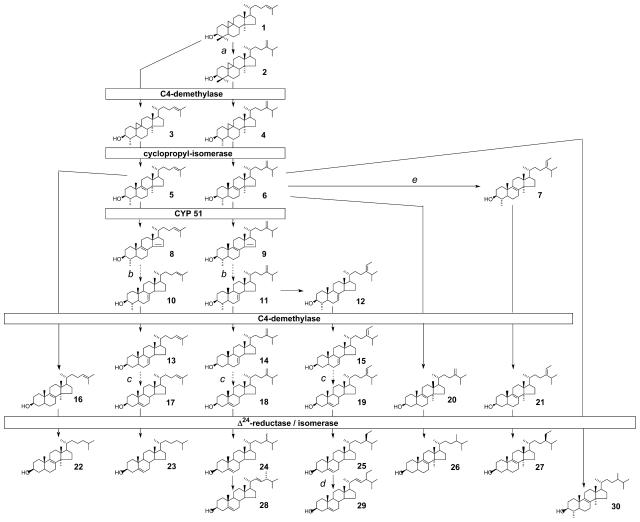

cyp51A2-3 Mutants Accumulate Obtusifoliol and 14α-Methyl Sterols

The role of Arabidopsis CYP51A2 in sterol biosynthesis was determined by comparing the sterol profiles of 1-month-old cyp51A2-3 plants with wild type (Table I). Mutant plants accumulated 63% of 14α-methyl-sterols, including obtusifoliol, the preferred substrate of the plant CYP51 (Taton and Rahier, 1991; Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1999), up to 7%, and its metabolites demethylated at position C4 (14α-methyl-fecosterol up to 10%) and/or presented a reduced C24(241) double bond [14α-methyl-24(241)-dihydrofecosterol up to 32%, 24(241)-dihydro-obtusifoliol up to 4%]. This accumulation resulted in a decreased amount of Δ5-sterols such as campesterol, sitosterol, and stigmasterol. The sterol biosynthetic pathway inferred from the sterol profile of cyp51A2-3 is shown in Figure 7 and is fully in accordance with the previous work in which plants were treated with triazole derivatives, inhibitors of obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase (Burden et al., 1989; Schaller et al., 1993). The results shown in Table I indicate that cyp51A2-3 is depleted of the pathway end products such as brassicasterol, cholesterol, 24-methylene cholesterol, campesterol, isofucosterol, sitosterol, and stigmasterol, when compared to the wild type. The biochemical analysis also showed that cyp51A2-3 plants contained only 44% of the total sterols found in wild-type plants, indicating that the biosynthetic flux is reduced in the mutant. Additionally, intermediates upstream of obtusifoliol, such as cycloartenol, accumulate significantly in the mutant.

Table I.

Sterol profile of cyp51A2-3 allele

| Sterol % | Ws-2 | cyp51A2-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Triterpenes (pentacyclic) | 3 | 2.5 |

| Cycloartenol (1) | 1 | 10 |

| 24-Methylene cycloartanol (2) | 0.5 | 2 |

| Cycloeucalenol (4) | 2 | nd |

| Obtusifoliol (6) | 1 | 7 |

| 24(241)-Dihydro-obtusifoliol (30) | nd | 4 |

| 241-Methyl-obtusifoliol (7) | nd | 1 |

| 14α-Methyl-Δ8-cholestenol (22) | nd | 2 |

| 14α-Methyl-zymosterol (16) | nd | 2 |

| 14α-Methyl-fecosterol (20) | nd | 10 |

| 14α-Methyl-24(241)-dihydrofecosterol (26) | nd | 32 |

| 14α,241-Dimethyl-fecosterol (21) | nd | 5 |

| 14α-Methyl-Δ8-sitostenol (27) | nd | tr |

| Δ7-Sitostenol | 0.5 | nd |

| Brassicasterol (28) | 2.5 | nd |

| Cholesterol (23) | 2 | tr |

| 24-Methylene cholesterol (18) | 1.5 | tr |

| Campesterol (24) | 13 | 1.5 |

| Isofucosterol (19) | 3 | 1 |

| Sitosterol (25) | 64 | 16 |

| Stigmasterol (29) | 6 | 2 |

| Total sterols μg/g DWa | 1,920 | 850 |

The se for the quantification of total sterol amounts is 12%. Numbers in parentheses refer to the sterol intermediates (sterols indicated in Fig. 7). nd, Not detected; tr, trace amount; DW, dry weight.

Figure 7.

Postsqualene sterol pathway in the cyp51A2-3 mutant. Sterol molecules are numbered and the nomenclature of detected compounds is given in Table I. The sterol profile of a wild-type Arabidopsis seedling consists mainly of campesterol (compound 24) and sitosterol (compound 25), which are the end products of the 24-methyl sterol biosynthetic segment of the pathway and of the 24-ethyl sterol segment of the pathway, respectively. A knockout of the gene encoding CYP51 leads in cyp51A2-3 seedlings to a sterol profile that results from the accumulation of obtusifoliol, principally compound 6, and of its metabolites bearing a demethylated C4 position and/or a reduced side chain. The dashed arrows indicate more than one biosynthetic step not indicated in this scheme. Relevant biosynthetic enzymes are indicated as follows: a, cycloartenol-C24-methyltransferase (SMT1); b, Δ14-reductase (FACKEL) then Δ8-Δ7-isomerase (HYDRA1); c, C5-desaturase (STE1/DWARF7) then Δ7-reductase (DWARF5); d, C22-desaturase; and e, 24-methylene lophenol-C241-methyltransferase (SMT2).

Overexpression of CYP51A2 and Molecular Complementation of cyp51A2-3 Mutants with the CYP51A2 Transgene

There are several reports describing phenotypes of transgenic plants overexpressing genes involved in sterol and BR biosynthetic pathways. For example, transgenic plants overexpressing sterol C-24 methyl transferase (SMT2), which is a branching point enzyme between the campesterol and sitosterol pathways, accumulated sitosterol at the expense of campesterol and displayed a reduced stature and growth that could be restored by BR treatment (Schaeffer et al., 2000, 2001). The ectopic expression of DWF4, involved in the early BR-specific biosynthetic pathway, resulted in increased vegetative growth and seed yield as well as elongated hypocotyl length in light and dark conditions (Choe et al., 2001). To document changes in plant development and/or sterol content caused by the overexpression of the Arabidopsis CYP51A2 gene, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants ectopically expressing CYP51A2. The transgenic plants had no morphological changes and also no significant changes in phytosterol content (data not shown).

The transgenic plants overexpressing CYP51A2 did not show any noticeable changes in morphological and biochemical phenotypes, while cyp51A2-3 mutants showed a seedling-lethal phenotype. To further confirm the functional role of the CYP51A2 gene, the transgenic plants expressing CYP51A2 were crossed to the cyp51A2-3 allele. The homozygous cyp51A2-3 plants containing the CYP51A2 cDNA transgene were comparable to wild-type or transgenic plants overexpressing CYP51A2 in appearance and fertility (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Molecular complementation of the cyp51A2-3 mutant by ectopic expression of CYP51A2. The homozygous cyp51A2-3 mutant containing the 35S::CYP51A2 transgene (right) has no differences in plant stature and fertility compared with wild-type (left) and transgenic plants overexpressing CYP51A2 (middle). F2 plants from the crosses between the heterozygous cyp51A2-3 mutants and the homozygous transgenic plants overexpressing CYP51A2 were selected from Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin (for selection of cyp51A-3 mutant) and gentamycin (for selection of the transgenic plants containing 35S::CYP51A2). The plants resistant to both antibiotics were subjected to the genotyping by PCR.

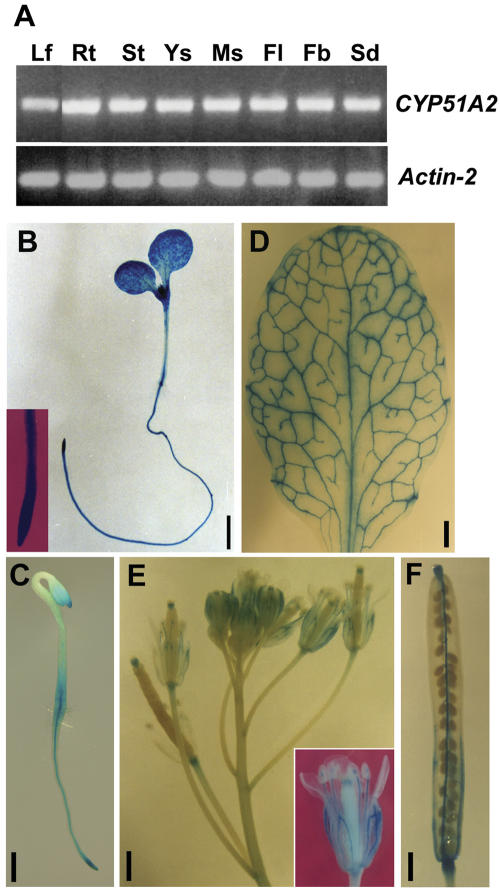

Expression Patterns of CYP51A2 Gene

Both RT-PCR and CYP51A2::GUS fusion studies were employed to study the expression patterns of the CYP51A2 gene. RT-PCR analysis showed that CYP51A2 was evenly expressed in all tissues examined (Fig. 9A). We generated transgenic lines containing promoter-GUS constructs to visualize the spatial and relative activity of the CYP51A2 gene expression. The promoter region of CYP51A2 (1,550 bp) amplified from Arabidopsis genomic DNA was fused to the β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene. The homozygous lines segregating for a single T-DNA insertion were subjected to GUS histochemical analyses. In light- and dark-grown seedlings, GUS activities were detected in the whole seedlings (Fig. 9, B and C). In the mature plant, GUS activities were strongly detected in rosette leaves (in veins and mesophyll tissues; Fig. 9D), flowers (in sepals, stamens, stigmas, and the distal end of pedicle; Fig. 9E), and mature siliques (in stigma, placenta, carpel wall, funiculi, and the distal part of pedicle; Fig. 9F), respectively. These constitutive expression patterns are similar to those observed in FACKEL, SMT1, SMT2, and SMT3 genes (Diener et al., 2000; Jang et al., 2000; Carland et al., 2002).

Figure 9.

Expression pattern analyses of CYP51A2 in various tissues. A, RT-PCR analysis revealed constitutive expression of CYP51A2 in various tissues, including leaves (Lf), 2-week-old roots grown on Murashige and Skoog medium (Rt), stems (St), young siliques (Ys), mature siliques (Ms), flowers (Fl), floral buds (Fb), and light-grown seedlings (Sd). Except for roots, tissues were collected from 5-week-old wild-type plants, ecotype Col-0. Actin-2 was used as a positive control. B, GUS activities in CYP51A2::GUS transgenic plants were detected in light- and dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings (B and C, respectively), rosette leaves (D), flowers (E), and mature siliques (F). Bar = 1 mm (B and D–F); bar = 0.5 mm (C).

DISCUSSION

Based on the biochemical and phenotypic characterization of mutants defective in sterol biosynthesis and the transgenic plants overexpressing or cosuppressing the genes in the pathway, it has been suggested that plant sterols influence plant growth and development (Clouse, 2000, 2002; Schaller, 2003). Recently, He et al. (2003) provided a molecular basis for this notion by analyzing the expression profile of marker genes. They showed that the expression pattern of marker genes in sterol-deficient mutants fk and dwf1/dim1 is different from that of the BR-deficient mutants det2 and dwf4. This result indicates that plant sterols and BRs have differential effects on regulating gene expression in Arabidopsis and therefore play sterol- and BR-specific roles to regulate plant development.

We show here that the loss-of-function mutation for Arabidopsis CYP51A2 resulted in accumulation of the substrate for the enzyme, obtusifoliol, and of its metabolites, indicating that CYP51A2 encodes a functional demethylase enzyme. We showed a high leakage of membrane ions in cyp51A2 mutant seedlings, supporting the idea that a major deficiency in the phytosterol composition of the cells leads to seedling lethality. The defects in cell elongation in cyp51A2 mutants were not corrected by exogenous BR application, although the BR-signaling cascade is probably still operating in the mutants. Taken together with the previous results, our data strongly support the hypothesis that plant sterols play essential roles in the regulation of plant growth and development by BR-dependent (as a precursor for BR biosynthesis) and -independent mechanisms (sterol-specific roles).

Two CYP51 Genes in Arabidopsis

Most organisms possess a single CYP51 gene, but plants appear unique in this regard, with, for example, the rice genome containing 10 putative CYP51 genes. The Arabidopsis genome contains two CYP51 genes, CYP51A1 and CYP51A2, which show differential expression patterns; CYP51A1 is expressed in root tissues (data not shown), whereas CYP51A2 is ubiquitously expressed (Fig. 9). The two CYP51 genes in Arabidopsis have different gene structures (Fig. 1A). The CYP51A2 gene had two introns, whereas the CYP51A1 gene had only a single intron in the coding region of the gene (Fig. 1A). We failed to detect putative intron(s) in the 2-kb region upstream of the start codon of CYP51A1 when we analyzed the region using the NetPlantGene program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/biolinks/pserve2.html).

More importantly, the cDNA sequence of CYP51A1 that we cloned in this study revealed that the current annotation for the gene (At2g17330) is incorrect. In fact, our result shows that exon 1 of CYP51A1 contains a stop codon resulting in a truncated 145-amino acid reading frame that obviously cannot encode a functional P450 enzyme. CYP51A1 of Arabidopsis should therefore be considered a pseudogene. Because CYP51A1 still has a tissue-specific expression typical of a full-length transcript, it is probably a recent pseudogene. One evolutionary scenario is that, following the CYP51 gene duplication, the Phe-to-Leu mutation in the heme-binding region rendered the protein enzymatically inactive. Indeed, an aromatic residue at this position is important in heme incorporation and interaction with redox partners. Relaxation of selection on the CYP51A1 gene then allowed the nucleotide 435 deletion. Alternatively, the exon 1 nucleotide deletion occurred first, but with a similar consequence.

Loss-of-function mutants of CYP51A2 resulted in various morphological changes, including seedling lethality and defects in cell elongation (in the cyp51A2-3 allele), retarded growth and sterility (in the cyp51A2-2 allele), and photomorphogenic development in the dark condition and distorted membrane integrity (in both alleles) (Figs. 2–4 and 6B). The ectopic expression of CYP51A2 cDNA also corrected the defects observed in the cyp51A2-3 allele (Fig. 8), whereas the CYP51A1 gene failed to complement the cyp51A2-3 allele (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Taken together, these data indicate that the CYP51A2 gene is the only functional obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase gene in the Arabidopsis genome. Complementation of the erg11 deficiency in yeast by CYP51A2 (Kushiro et al., 2001) provides additional support for the functional role of CYP51A2 as a 14α-demethylase.

Membrane Integrity in CYP51A2 Mutants

The bulk sterols, sitosterol and 24-methylcholesterol, are the most efficient sterols for regulating the mobility of phospholipid fatty acyl chains in plant cells. These two sterols also appear to be very active in reducing membrane permeability, stigmasterol being comparatively very inefficient (Hartmann, 1998). In the cyp51A2-3 mutants, the two bulk sterols were greatly reduced (Table I) and membrane integrity was defective in proportion to the phenotype severity of the cyp51A2 alleles (Fig. 6B). An appropriate sterol composition is crucial for optimal activity of membrane-bound enzymes and signal transduction components, ion and metabolite transport, and protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions (Schaller, 2003) or distribution (Pike, 2004). For instance, the plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity was modulated by the changed sterol composition. Stigmasterol stimulated H+ pumping of H+-ATPase, while the unusual sterols, such as 14α-methyl-Δ8-sterols, behaved as inhibitors (Grandmougin-Ferjani et al., 1997). The accumulation of 14α-methyl-Δ8-sterols is pronounced in the cyp51A2 mutant (Table I). Along these lines, transgenic tobacco cosuppressing plasma membrane H+-ATPase resulted in stunted and delayed plant growth and male fertility or sterility (Zhao et al., 2000). A sterol mutant, smt1, showed hypersensitivity to calcium ions and was proposed to result from altered membrane permeability in the mutant (Diener et al., 2000). Recent evidence revealed that reduced sterol content also impaired the proper localization of auxin efflux proteins, PIN proteins (Willemsen et al., 2003), and hormone signaling (Souter et al., 2002). Taken together, these results suggest that the developmental defects observed in cyp51A2 mutants (Figs. 2–4) may be caused by defective membranes due to the changed sterol composition, which in turn affects membrane proteins. The yellow or pale green color in the leaf margin and along veins of the cyp51A2-2 mutant might be caused by uncontrolled ion leakage or uptake (Fig. 4A, inset).

BR Signaling in CYP51A2 Mutants

Exogenous BR did not rescue the defects observed in cyp51A2-3. This failure is not likely to be associated with a defect in BR signaling in cyp51A2 mutants with distorted membrane integrity. BR biosynthetic genes, such as DWF4 and CPD, are known to be controlled by a feedback regulation mechanism through a signaling cascade that requires the function of the BR receptor BRI1 (Bishop and Koncz, 2002). DWF4 and CPD expression levels in the cyp51A2-3 mutant were down-regulated as much as in wild type upon BR treatment (Fig. 6A). This indicates that the BR-signaling cascade is normal in the cyp51A2 mutant, although membrane integrity was affected (Fig. 6B). This result also indicates that BR-signaling components, including the BR receptor, are properly localized into the plasma membrane of the mutant.

Embryogenesis in CYP51A2 Mutants

There was no change in the cotyledon number of cyp51A2-3 seedlings when compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, smt1 (Diener et al., 2000; Willemsen et al., 2003), fk/hydra2, and hyd1 mutants (Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000; Souter et al., 2002) displayed multiple cotyledons. In these sterol-deficient mutants, multiple cotyledon primordia were already developed in early embryogenesis, indicating that plant sterols are involved in cotyledon developmental patterning. Generally, cotyledon development is embryonically determined. cyp51A2-3 heterozygous plants did not segregate for abnormal embryos in the developing siliques (Fig. 5A), although the morphology of mature seeds was changed (Fig. 5B). Perhaps the 14α-methyl Δ8-sterols that accumulated in cyp51A2 mutants could be at least partially active during early embryogenesis in the mutant. Among atypical sterols, 8,14-diene sterols accumulated in fackel mutants and 5α-cholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol affected the expression of genes involved in cell expansion and cell division (He et al., 2003), although fackel mutants displayed defects in early embryogenesis (Jang et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2000).

Complexity of Sterol Biosynthetic Pathways in Arabidopsis

Plant sterols are derived from mevalonic acid through methylation, reduction, isomerization, and desaturation steps to produce membrane sterols (i.e. sitosterol and stigmasterol) and also precursors of plant growth hormone BRs (campesterol). Recent studies suggest that the plant sterol biosynthetic pathway is a complex pathway with branches rather than a simple linear pathway. For instance, loss-of-function Arabidopsis mutants for SMT1 highly accumulated cholesterol, which is present in minute amounts in wild-type plants and under normal growth conditions (Diener et al., 2000; Schrick et al., 2002; Willemsen et al., 2003). Both hydra1 and fk/hydra2 accumulated stigmasterol compared to wild type (Souter et al., 2002). Atypical Δ8,14-diene sterols that are not detected in normal conditions were accumulated in Arabidopsis fackel mutants (Schrick et al., 2000) and wild-type plants treated with the sterol analog inhibitor 15-azasterol (Schaller, 2003), indicating a biosynthetic block at the Δ14-reduction step. The loss-of-function mutation in the Arabidopsis CYP51A2 gene resulted in the accumulation of 14α-methyl sterols with the depletion of Δ5 sterols such as sitosterol, stigmasterol, and campesterol, demonstrating that the C-14 demethylation step is blocked by the mutation (Table I). The accumulation of 14α-methyl sterol forms in plant cells was also observed by the treatment of triazole derivatives (Schaller et al., 1993). The end products of plant sterol biosynthesis, such as sitosterol, stigmasterol, and campesterol, are still detected in relatively large amounts in the sterol biosynthetic mutants, including the cyp51A2 mutant (Table I). These results suggest the presence of branch pathways, which are quiet under normal conditions and might be activated by specific growth conditions and eventually produce the final end products. We can also propose that the amount of campesterol and sitosterol in cyp51A2-3 may be of maternal origin, based on the fact that sterol biosynthesis genes are expressed in endosperm (Grebenok et al., 1997).

Ectopic Overexpression of the CYP51A2 Gene in Arabidopsis

In the sterol biosynthetic pathway, SMT1 (cycloartenol C-24 methyltransferase) and SMT2 (24-methylene lophenol C-241 methyltransferase) serve as branch points between cholesterol and the sterols modified with ethyl or methyl groups at the C-24 position (sitosterol and campesterol), and between 24-methyl sterols (campesterol) and 24-ethyl sterols (sitosterol and stigmasterol), respectively (Schaller, 2003). Arabidopsis plants that overexpress SMT2 contain higher levels of sitosterol and lower levels of campesterol, and exhibit morphological changes, including short stature and reduced growth rate (Schaeffer et al., 2001). The transgenic tobacco plants that overexpress SMT1 have decreased cholesterol and increased sitosterol and 24-methyl cholesterol without significant effects on plant growth and development (Sitbon and Jonsson, 2001). Overexpression of DWF4 (CYP90B1, steroid 22α-hydroxylase), which mediates a rate-limiting step in BR biosynthesis, resulted in increased vegetative growth and seed yield with increased levels of BR intermediates (Choe et al., 2001). In contrast to these results, transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing CYP51A2 showed no change in sterol profiles and morphology (data not shown), indicating that sterol 14α-demethylation is not a limiting step in sterol biosynthesis and/or that the levels of 14-demethylated sterols are tightly regulated by feedback. A more likely scenario is that, since very little obtusifoliol, the substrate for the enzyme, is detected in wild-type plants, an elevated level of enzyme, due to the overexpression of the transgene, has no effect on metabolic flux. Likewise, the sterol content of Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the FPS1S isoform of farnesyl diphosphate synthase in mevalonic acid biosynthesis is very similar to that of control plants (Masferrer et al., 2002). These results indicate that the sterol levels in plants are probably under tight regulation. The fact that a very small fraction of the bulky sterols synthesized in plants is used for BR biosynthesis further supports the existence of tight control for the sterol pathway (Benveniste, 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotypes Ws-2 and Col-6 (glabra1) were used as wild types for transformation and crossing, respectively. For in vivo culture, seeds were surface sterilized (20% commercial bleach and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 10 min, washed three times with sterile distilled water, and dried with 95% ethanol. The seeds were sprinkled on 0.8% agar-solidified media containing 1× Murashige and Skoog (1962) salts and 1% Suc (pH 5.8 with KOH). For Murashige and Skoog media containing kanamycin, 40 μg/mL kanamycin was added to the media. Seeds were planted on soil (Metromix 350; Grace-Sierra, Milpitas, CA) presoaked with distilled water. The pots were covered with plastic wrap and cold treated at 4°C for 2 d before transfer to a growth chamber (16-h-light period at 150 μmol−2 s−1, 70% humidity, at 22°C). The plastic wrap was removed after the appearance of the first leaves. The pots were subirrigated in distilled water as required.

Isolation of Mutant Lines

To isolate knockout lines for Arabidopsis CYP51 genes, 80,000 T-DNA-tagged lines (120,000 inserts) were screened by a reverse genetics approach described previously (Krysan et al., 1996; Winkler et al., 1998). The T-DNA-tagged lines used in this study include Feldmann lines (6,000 individual lines; Winkler et al., 1998), Thomas Jack lines (6,000 individual lines; Campisi et al., 1999), and 60,480 individual lines from the Arabidopsis Knockout Facility at the Biotechnology Center of the University of Wisconsin (Krysan et al., 1999). Briefly, PCR primers, which were generally 29-mers, were designed to amplify the wild-type gene; for CYP51A1, CYP51A1F, 5′-TGTCATTCAGCATATACTTTGATTCCGC-3′, CYP51A1R1, 5′-AGTAGCCAAATTCCAAACTTCGTGGTGT-3′; for CYP51A2, CYP51A2F, 5′-CGTCTCTGAAACTCCATCATCGTATCAA-3′, CYP51A2R, 5′-CCGTATAAATGAGCACATTTGCAGAACC-3′. These primers were used in combination with a T-DNA-specific primer to detect insertions within the CYP51 genes. ExTaq polymerase (PanVera LLC, Madison, WI) was used as a highly processive Taq polymerase. PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation at 96°C for 5 min; 94°C for 15 s, 65°C for 30 min, and 72°C for 2 min (total 36 cycles); and final extension for 5 min at 72°C. Southern hybridizations and sequencing were done to verify the T-DNA insertion in each gene. Isolated individual plant lines were genotyped with PCR containing both gene-specific primers and the T-DNA border primer. Isolated mutant lines were back-crossed to wild type to remove background mutations.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA (1 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript RNaseH− reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD). The conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: 96°C for 5 min for initial denaturation, followed by 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (total 25 cycles) with 5 min of final extension at 72°C. The primers for RT-PCR were designed from mostly 3′-UTR for gene-specific amplification; for CYP51A1, 51A1RT-F, 5′-AAGATCTTACTGCTGAGAACAGTA-3′, 51A1RT-R, 5′-TACGATCAAACAAGCAACATAACAA-3′; for CYP51A2, 51A2RT-F, 5′-CTCATCATGTTAATGAGAGCCTCG-3′, 51A2RT-R, 5′-GCAGAACCAACAAACTTAGGAAGCT-3′. The actin-2 transcript was amplified as a positive control. The primer sequences are as follows: ACT2RT-F, 5′-AGTGTGTCTTGTCTTATCTGGTTCG-3′, and ACT2RT-R, 5′-AATAGCTGCATTGTCACCCGATACT-3′.

RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL). From each sample, 10 μg of total RNA were separated on a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-NX membrane (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) by a capillary-blotting method. The RNA blots were hybridized overnight with a 32P-labeled DNA probe under the following conditions: 6× SSC (0.9 m NaCl, 0.09 m sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.3% SDS at 65°C. The hybridized blots were washed at 65°C while gradually decreasing the salt concentration to 0.5× SSC/0.1% SDS, and exposed to x-ray film (Fuji, Tokyo).

Generation of Promoter Construct and GUS-Staining Procedures

A genomic fragment containing the promoter region of CYP51A2 was amplified by Pwo polymerase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with a pair of primers. The promoter fragment included a partial open reading frame so that a translational fusion with the GUS gene could be made. Restriction enzyme sites, BamHI and XbaI, were introduced into the primers for cloning of the PCR product. The primer sequences are as follows: 51A2PFBm, 5′-CGGGATCCTGTTGAAAATTCTCAACATGATAATCCA-3′, 51A2PRXb, 5′-GCTCTAGACAATTTGTTCTCCGAATCCAATTCCAT-3′ (bold letters indicate the complementary sequence corresponding to translation start codon, ATG). The PCR product was cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The complete nucleotide sequences of the PCR product were determined to check for PCR error. The restriction fragment of the PCR product, BamHI/XbaI fragment, was subcloned into the BamHI/SpeI site of pCAMBIA1303 binary vector (CAMBIA, Canberra, Australia), replacing the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter of the vector. The promoter construct was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) by electroporation and introduced into Ws-2 plants using the floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic plants were selected on Murashige and Skoog plates containing hygromycin (40 μg/mL). The homozygous transgenic lines containing the promoter constructs were selected from the T3 generation. Plants and plant tissues were stained for GUS according to the method of Stomp (1992). GUS-stained tissues were dehydrated through an ethanol series.

Overexpression of CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 in Arabidopsis

A genomic fragment containing the coding region of CYP51A1 was amplified by Pwo polymerase (Roche) with a pair of primers. Restriction enzyme sites of EcoRI and KpnI were introduced into the primers for cloning of the PCR product. The primer sequences are as follows: 51A1EcF, 5′-CGGAATTCTAACGAGAGAAAAAAATGGACTGGGAT-3′, 51A1KpR, 5′-GGGGTACCGTGTCTACTTTACAAATAAACCCTTGT-3′. The PCR products were cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene). The complete nucleotide sequence of the PCR product was determined to check for PCR errors. An EcoRI/KpnI fragment of the PCR product was subcloned between the CaMV 35S promoter and the poly(A) signal of pRT101 (Töpfer et al., 1987). The full-length cDNA clone for CYP51A2 (expressed sequence tag no. AA720360) was donated by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). An EcoRI/BamHI fragment from the CYP51A2 cDNA clone was subcloned between the CaMV 35S promoter and the poly(A) signal of pRT101. PstI fragments containing the overexpression cassettes from pRT101 were subcloned into the binary vector, pPZP221 (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994). The overexpression cassettes in pPZP221 were transformed into A. tumefaciens (GV3101) by electroporation and introduced into Ws-2 plants as described above. Transgenic plants were selected on Murashige and Skoog plates containing gentamycin (80 μg/mL). Homozygous transgenic lines overexpressing CYP51A1 and CYP51A2 were selected in the T3 generation.

Molecular Complementation of the cyp51A2-3 Mutant by CYP51A2

Transgenic homozygous lines overexpressing CYP51A2 were crossed to a plant heterozygous for the cyp51A2-3 mutation. Transgenic plants overexpressing CYP51A2 and the cyp51A2-3 mutants contain gentamycin- and kanamycin-resistant markers, respectively. The F1 plants were selected on the Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin (40 μg/mL) and gentamycin (80 μg/mL) and selfed to get F2 seeds. The F2 plants were selected on Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin and gentamycin again and genotyped for the cyp51A2-3 mutation.

Analysis of Sterol Content

Arabidopsis Ws-2 and cyp51A2 mutants were grown for 1 month on Murashige and Skoog (1% Suc) medium. The lyophilized material was saponified with 6% KOH in methanol at 80°C for 2 to 3 h. Sterols were extracted with 3 volumes of n-hexane. The dried residue was subjected to an acetylation reaction for 1 h at 70°C in toluene with a mixture of pyridine/acetic anhydride in equivalent proportions. Steryl acetates were resolved by thin-layer chromatography on Merck precoated silica plates with one run of dichloromethane as a single band (Rf = 0.5). Purified steryl acetates were separated and identified by gas chromatography (GC) using a Varian 8300 gas chromatograph (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) with flame ionization detection, a glass capillary column (DB1), and H2 as a carrier gas (2 mL min−1). The temperature program included a steep ramp from 60°C to 220°C (30°C min−1) followed by a 2°C min−1 ramp from 220°C to 280°C. Data from the detector were monitored with the Varian Star computer program. Amounts of steryl acetates were quantified using cholesterol as an internal standard. Sterol structures were confirmed by GC-mass spectrometry (MS) carried out on sterol fractions prepared as follows. The hexane extract was resolved on thin-layer chromatography Merck plates as 4-desmethylsterols (Rf = 0.2), 4α-methylsterols (Rf = 0.3), and 4,4-dimethylsterols (Rf = 0.4) with two runs of dichloromethane as developing solvent. Sterol fractions were scraped off and derivatization was done as described above. GC-MS runs were done on an Agilent 6890 GC system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a DB5 column coupled to a mass detector. Identification of 14α-methyl-Δ8-sterols was done according to published data (Schmitt and Benveniste, 1979).

Measurement of Membrane Ion Leakage

Membrane ion leakage was determined by measuring electrolytes leaked from whole seedlings. Seedlings were immersed in 3 mL of a solution of 400 mm mannitol at 22°C with gentle shaking for 3 h, and the initial conductivity was then measured. Total conductivity was determined after boiling for 10 min. The conductivity was expressed as a percentage of the initial conductivity as compared to the total conductivity.

Microscopic Analysis

Seedlings were fixed in formaldehyde-acetic acid (FAA) overnight at 4°C, dehydrated through an ethanol series, infiltrated with xylene, and embedded in Paraplast (Oxford, St. Louis). The tissue sections (10 μm thick) were transferred to Poly-l-lysine-coated slides (Sigma, St. Louis), deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated through an ethanol series, and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue. The stained sections were dehydrated through an ethanol series and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Light microscopy was performed with a Nikon E600 model (Tokyo).

Tissue and whole-mount analyses were prepared as described (Berleth and Jürgens, 1993) and viewed under bright- and dark-field illumination in a dissecting microscope. Observation of embryos required the overnight fixation of siliques in an ethanol:acetic acid (9:1) solution. The siliques were rinsed in 90% and 70% ethanol solutions and cleared with chloral hydrate:glycerol:water (8:1:2) solution. The cleared siliques were dissected under a binocular microscope and the seeds observed with a Leitz microscope.

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third-party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requester.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession number AY666123.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Human Frontier Science Program (grant no. RG0280/1999–M), in part by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (grant no. R01–2001–000–00104–0 to C.S.A.), in part by a grant from the Environmental Biotechnology National Core Research Center, Gyeongsang National University (to C.-H.G.), in part by a grant from the Plant Metabolism Research Center at Kyung Hee University (Science Research Center Program from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation to S.C.), and by the BK21 Research Program from the Korean Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development (to H.B.K.).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.105.061598.

References

- Bak S, Kahn RA, Olsen CE, Halkier BA (1997) Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the obtusifoliol 14 alpha-demethylase of Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench, a cytochrome P450 orthologous to the sterol 14 alpha-demethylases (CYP51) from fungi and mammals. Plant J 11: 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste P (2002) Sterol metabolism. In CR Somerville, EM Meyerowitz, eds, The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, http://www.aspb.org/publications/arabidopsis/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berleth T, Jürgens G (1993) The role of the monopterous gene in organizing the basal body region of the Arabidopsis embryo. Development 118: 575–587 [Google Scholar]

- Bishop GJ, Koncz C (2002) Brassinosteroids and plant steroid hormone signaling. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14: S97–S110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burden RS, Cooke DT, Carter GA (1989) Inhibitors of sterol biosynthesis and growth in plants and fungi. Phytochemistry 28: 1791–1804 [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Benveniste P, Schaller H (2003) Virus-induced silencing of sterol biosynthetic genes: identification of a Nicotiana tabacum L. obtusifoliol-14alpha-demethylase (CYP51) by genetic manipulation of the sterol biosynthetic pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana L. J Exp Bot 54: 1675–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Hurtado F, Taton M, Forthoffer N, Kahn R, Bak S, Rahier A, Werck-Reichhart D (1999) Optimized expression and catalytic properties of a wheat obtusifoliol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51) expressed in yeast. Complementation of erg11 delta yeast mutants by plant CYP51. Eur J Biochem 262: 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi L, Yang Y, Yi Y, Heilig E, Herman B, Cassista JA, Allen DW, Xiang H, Jack T (1999) Generation of enhancer trap lines in Arabidopsis and characterization of expression patterns in the inflorescence. Plant J 17: 699–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carland FM, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Nelson T (2002) The identification of CVP1 reveals a role for sterols in vascular patterning. Plant Cell 14: 2045–2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S, Dilkes BP, Gregory BD, Ross AS, Yuan H, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Tanaka A, Yoshida S, et al (1999. a) The Arabidopsis dwarf1 mutant is defective in the conversion of 24-methylenecholesterol to campesterol in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 119: 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S, Fujioka S, Noguchi T, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Feldmann KA (2001) Overexpression of DWARF4 in the brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway results in increased vegetative growth and seed yield in Arabidopsis. Plant J 26: 573–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Tissier CP, Gregory BD, Ross AS, Tanaka A, Yoshida S, Tax FE, et al (1999. b) The Arabidopsis dwf7/ste1 mutant is defective in the delta(7) sterol C-5 desaturation step leading to brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 11: 207–221 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S, Tanaka A, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Ross AS, Tax FE, Yoshida S, Feldman KA (2000) Lesions in the sterol delta(7) reductase gene of Arabidopsis cause dwarfism due to a block in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant J 21: 431–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD (2000) Plant development: a role for sterols in embryogenesis. Curr Biol 10: R601–R604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD (2002) Arabidopsis mutants reveal multiple roles for sterols in plant development. Plant Cell 14: 1995–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Sasse JM (1998) Brassinosteroids: essential regulators of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 49: 427–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeljak N, Fink M, Rozman D (2003) Many facets of mammalian lanosterol 14alpha-demethylase from the evolutionary conserved cytochrome P450 family CYP51. Arch Biochem Biophys 409: 159–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener AC, Li HX, Zhou WX, Whoriskey WJ, Nes WD, Fink GR (2000) STEROL METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 controls the level of cholesterol in plants. Plant Cell 12: 853–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards PA, Ericsson J (1999) Sterols and isoprenoids: signaling molecules derived from the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 157–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandmougin-Ferjani A, Schuler-Muller I, Hartmann M-A (1997) Sterol modulation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity from corn roots reconstituted into soybean lipids. Plant Physiol 113: 163–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebenok RJ, Galbraith DW, DellaPenna D (1997) Characterization of Zea mays endosperm C-24 sterol methyltransferase: one of two types of sterol methyltransferase in higher plants. Plant Mol Biol 34: 891–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P (1994) The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacterium binary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol 25: 989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M-A (1998) Plant sterols and the membrane environment. Trends Plant Sci 3: 170–175 [Google Scholar]

- He J-X, Fujioka S, Li T-C, Kang SG, Seto H, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Jang J-C (2003) Sterols regulate development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 131: 1258–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husselstein T, Schaller H, Gachotte D, Benveniste P (1999) Delta(7)-sterol-C5-desaturase: molecular characterization and functional expression of wild-type and mutant alleles. Plant Mol Biol 39: 891–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JC, Fujioka S, Tasaka M, Seto H, Takatsuto S, Ishii A, Aida M, Yoshida S, Sheen J (2000) A critical role of sterols in embryonic patterning and meristem programming revealed by the fackel mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev 14: 1485–1497 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen CB, Billheimer JT, Summers SA, Stayrook SE, Lewis M, Strauss JF III (1998) Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) is a sterol transfer protein. J Biol Chem 273: 26285–26288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauschmann A, Jessop A, Koncz C, Szekeres M, Willmitzer L, Altmann T (1996) Genetic evidence for an essential role of brassinosteroids in plant development. Plant J 9: 701–713 [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yokota T, Nomura T, Yoshida S, Chua NH (1998) The Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1 gene encodes a protein involved in steroid synthesis. Plant Cell 10: 1677–1690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan PJ, Young JC, Sussman MR (1999) T-DNA as an insertional mutagen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11: 2283–2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan PJ, Young JC, Tax F, Sussman MR (1996) Identification of transferred DNA insertions within Arabidopsis genes involved in signal transduction and ion transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8145–8150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushiro M, Nakano T, Sato K, Yamagishi K, Asami T, Nakano A, Takatsuto S, Fujioka S, Ebizuka Y, Yoshida S (2001) Obtusifoliol 14 alpha-demethylase (CYP51) antisense Arabidopsis shows slow growth and long life. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 285: 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masferrer A, Arro M, Manzano D, Schaller H, Fernandez-Busquets X, Moncalean P, Fernandez B, Cunillera N, Boronat A, Ferrer A (2002) Overexpression of Arabidopsis thaliana farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPS1S) in transgenic Arabidopsis induces a cell death/senescence-like response and reduced cytokinin levels. Plant J 30: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Schuler MA, Paquette SM, Werck-Reichhart D, Bak S (2004) Comparative genomics of rice and Arabidopsis: analysis of 727 cytochrome P450 genes and pseudogenes from a monocot and a dicot. Plant Physiol 135: 756–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Kawagoe Y, Hogan P, Delmer D (2002) Sitosterol-beta-glucoside as primer for cellulose synthesis in plants. Science 295: 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike LJ (2004) Lipid rafts: heterogeneity on the high seas. Biochem J 378: 281–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP, Aravind L (1999) START: a lipid-binding domain in StAR, HD-ZIP and signaling proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 24: 130–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer A, Bouvier-Nave P, Benveniste P, Schaller H (2000) Plant sterol-C24-methyl transferases: different profiles of tobacco transformed with SMT1 or SMT2. Lipids 35: 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer A, Bronner R, Benveniste P, Schaller H (2001) The ratio of campesterol to sitosterol that modulates growth in Arabidopsis is controlled by STEROL METHYLTRANSFERASE 2;1. Plant J 25: 605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller H (2003) The role of sterols in plant growth and development. Prog Lipid Res 42: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller H, Maillot-Vernier P, Gondet L, Belliard G, Benveniste P (1993) Biochemical characterization of tobacco mutants resistant to azole fungicides and herbicides. Biochem Soc Trans 21: 1052–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt P, Benveniste P (1979) Effect of fenarimol on sterol biosynthesis in suspension cultures of bramble cells. Phytochemistry 18: 1659–1665 [Google Scholar]

- Schrick K, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Stierhof YD, Stransky H, Yoshida S, Jurgens G (2004. a) A link between sterol biosynthesis, the cell wall, and cellulose in Arabidopsis. Plant J 38: 227–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrick K, Mayer U, Horrichs A, Kuhnt C, Bellini C, Dangl J, Schmidt J, Jurgens G (2000) FACKEL is a sterol C-14 reductase required for organized cell division and expansion in Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Genes Dev 14: 1471–1484 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrick K, Mayer U, Martin G, Bellini C, Kuhnt C, Schmidt J, Jurgens G (2002) Interactions between sterol biosynthesis genes in embryonic development of Arabidopsis. Plant J 31: 61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrick K, Nguyen D, Karlowski WM, Mayer KF (2004. b) START lipid/sterol-binding domains are amplified in plants and are predominantly associated with homeodomain transcription factors. Genome Biol 5: R41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitbon F, Jonsson L (2001) Sterol composition and growth of transgenic tobacco plants expressing type-1 and type-2 sterol methyltransferases. Planta 212: 568–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souter M, Topping J, Pullen M, Friml J, Palme K, Hackett R, Grierson D, Lindsey K (2002) hydra mutants of Arabidopsis are defective in sterol profiles and auxin and ethylene signaling. Plant Cell 14: 1017–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stomp A-M (1992) Histochemical localization of β-glucuronidase. In SR Gallagher, ed, GUS Protocols: Using the GUS Gene as a Reporter of Gene Expression. Academic Press. San Diego, pp 103–113

- Szekeres M, Nemeth K, Koncz-Kalman Z, Mathur J, Kauschmann A, Altmann T, Redei GP, Nagy F, Schell J, Koncz C (1996) Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of CYP90, a cytochrome P450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Cell 85: 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taton M, Rahier A (1991) Properties and structural requirements for substrate specificity of cytochrome P-450-dependent obtusifoliol 14 alpha-demethylase from maize (Zea mays) seedlings. Biochem J 277: 483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer R, Matzeit V, Gronenborn B, Schell J, Steinbiss H-H (1987) A set of plant expression vectors for transcriptional and translational fusions. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen V, Friml J, Grebe M, van den Toorn A, Palme K, Scheres B (2003) Cell polarity and PIN protein positioning in Arabidopsis require STEROL METHYLTRANSFERASE1 function. Plant Cell 15: 612–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler RG, Frank MR, Galbraith DW, Feyereisen R, Feldmann KA (1998) Systematic reverse genetics of transfer-DNA-tagged lines of Arabidopsis—isolation of mutations in the cytochrome P450 gene superfamily. Plant Physiol 118: 743–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Noshiro M, Aoyama Y, Kawamoto T, Horiuchi T, Gotoh O (1997) Structural and evolutionary studies on sterol 14-demethylase P450 (CYP51), the most conserved P450 monooxygenase. 2. Evolutionary analysis of protein and gene structures. J Biochem (Tokyo) 122: 1122–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Dielen V, Kinet JM, Boutry M (2000) Cosuppression of a plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase isoform impairs sucrose translocation, stomatal opening, plant growth, and male fertility. Plant Cell 12: 535–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.