Abstract

Gorham’s disease is a rare disorder characterized by proliferation of vascular channels that results in destruction and resorption of osseous matrix. Since the initial description of the disease by Gorham and colleagues (1954) and by Gorham and Stout (1955), fifty years have elapsed but still the precise etiology of Gorham’s disease remains poorly understood and largely unknown. There is no evidence of a malignant, neuropathic, or infectious component involved in the causation of this disorder. The mechanism of bone resorption is unclear.

The clinical presentation of Gorham’s disease is variable and depends on the site of involvement. It often takes many months or years before the offending lesion is correctly diagnosed. A high index of clinical suspicion is needed to arrive at an early, accurate diagnosis. Patients with Gorham’s disease may complain of dull aching pain or insidious onset of progressive weakness. In some cases, pathologic fracture often leads to its discovery. Gorham’s disease is progressive in most patients; however, in some cases, the disease process is self-limiting. The clinical course is generally protracted but rarely fatal, with eventual stabilization of the affected bone being the most common sequelae. Chylous pericardial and pleural effusions may occur due to mediastinal extension of the disease process from the involved vertebra, scapula, rib or sternum, and can be life threatening. A high morbidity and mortality is seen in patients with spinal and/or visceral involvement.

The medical treatment for Gorham’s disease includes radiation therapy, anti-osteoclastic medications (bisphosphonates), and alpha-2b interferon. Surgical treatment options include resection of the lesion and reconstruction using bone grafts and/or prostheses. In most cases, bone grafts tend to undergo resorption and are not helpful. Surgical reconstruction and/or radiation therapy are used for management of patients who have large, symptomatic lesions with long-standing, disabling functional instability. Surgical stabilization may be required for unstable spinal lesions. Various treatment options, including pleurectomy, pleurodesis, thoracic duct ligation, radiation therapy, interferon therapy, and bleomycin, have been used for management of patients with Gorham’s disease presenting with chylothorax. In general, no single treatment modality has proven effective in arresting the disease.

Keywords: Essential Osteolysis, Bone diseases, Bone resorption

A diverse group of primary or idiopathic disorders can lead to significant lysis of the skeleton. These osteolytic syndromes (table 1 ) differ in the presence or absence of genetic transmission, the associated clinical features, and the major locations of osteolysis. However, a detailed discussion of all these osteolytic disorders is beyond the scope of this overview and will, therefore, focus only on Gorham’s disease or massive osteolysis.

Table 1.

Differential Diagnoses of Osteolysis Syndromes.

| Massive osteolysis (Gorham’s disease) |

| Acro-osteolysis of Hajdu and Cheney |

| Idiopathic multicentric osteolysis (carpal-tarsal osteolysis) |

| Multicentric osteolysis with nephropathy |

| Hereditary multicentric osteolysis |

| Neurogenic osteolysis |

| Acro-osteolysis of Joseph |

| Acro-osteolysis of Shinz |

| Farber’s disease |

| Winchester’s syndrome |

| Osteolysis with detritic synovitis |

Adapted from Resnick D. Osteolysis and chondrolysis. In: Resnick D, ed. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. 4th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co.; 2002. 4920–4944.

Gorham’s disease, fortunately, is an extremely rare disorder of the musculoskeletal system. In 1954, Gorham and colleagues1 reported on two patients with massive osteolysis of the bone. Of the two cases, one was a boy, 16 years of age, with right clavicle and scapula involvement. This patient eventually developed chylothorax and expired. The other was a male, 44 years of age, who also had involvement of the right clavicle and scapula. In addition, these authors provided a brief review of 16 reported cases from the literature.

In 1955, Gorham and Stout2 provided a more comprehensive report on this subject. Based on their experience and the available case reports from the literature, they found that “Gorham’s disease is usually associated with an angiomatosis of blood vessels and sometimes of lymphatic vessels, which seemingly are responsible for it”. In the past 50 years, numerous papers3 – 147 have been published in medicine, orthopaedic surgery, general surgery, neurosurgery, otolaryngorhinology, plastic surgery, maxillofacial, and dental literature. On detailed review of the literature, it is evident that various eponyms (table 2 ) have been used to describe this mysterious disorder of the musculoskeletal system. The purpose of this review is to make the medical community aware of this rare entity, and to discuss the etiopathology, clinical presentation, radiographic findings, differential diagnoses, and treatment options for patients with Gorham’s disease.

Table 2.

Eponyms for Gorham’s Disease.

| Gorham’s Syndrome |

| Gorham-Stout Syndrome |

| Morbus Gorham-Stout Disease |

| Massive Osteolysis |

| Idiopathic Massive Osteolysis |

| Progressive Massive Osteolysis |

| Massive Gorham Osteolysis |

| Disappearing Bone Disease |

| Vanishing Bone Disease |

| Phantom Bone Disease |

Etiopathology

To date, the etiology and pathophysiology of this poorly understood disease remains undetermined. The pathological process is the replacement of normal bone by an aggressively expanding but non-neoplastic vascular tissue,57 , 97 , 113 , 116 similar to a hemangioma or lymphangioma. Wildly proliferating neovascular tissue causes massive bone loss. In the early stage of the lesion, the bone undergoes resorption, and is replaced by hypervascular fibrous connective tissue and angiomatous tissue. Histologically, involved bones show a non-malignant proliferation of thin-walled vessels; the proliferative vessels may be capillary, sinusoidal or cavernous. In late stages, there is progressive dissolution of the bone leading to massive osteolysis, with the osseous tissue being replaced by fibrous tissue. The stimulus that generates this change in the bone is unknown.97

One main structural feature of the lesion is the presence of unusually wide capillary-like vessels and, therefore, it is likely that the blood flow through these vessels is slow. It has been suggested that the slow circulation produces local hypoxia and lowering of the pH, favoring the activity of various hydrolytic enzymes.21 Heyden and colleagues21 observed strong activity of both acid phosphatase and leucine aminopeptidase in mononuclear perivascular cells that were in contact with remaining bone, perhaps indicating that these cells are important in the process of osseous resorption.

The exact nature of the disease process is unknown. The resemblance of the pathologic characteristics to those of hemangiomas, coupled with the presence of soft tissue hemangiomatous or lymphangiomatous tissue, has suggested to some investigators, including Gorham and Stout,2 that massive osteolysis represents a vascular derangement or a diffuse hemangiomatosis. Gorham and Stout2 maintained that active hyperemia, changes in local pH, and mechanical forces promote bone resorption. They hypothesized that trauma may trigger the process by stimulating the production of vascular granulation tissue, and that “osteoclastosis” is not necessary. In contrast, Devlin and colleagues97 have suggested that bone resorption in patients with Gorham’s disease is due to enhanced osteoclast activity, and that interleukin-6 (IL-6) may play a role in the increased resorption of bone. Moller and associates125 reported six cases of Gorham-Stout syndrome with histopathological findings and presented evidence that osteolysis is due to an increased number of stimulated osteoclasts.

Dickson and colleagues46 have reported on cytochemical investigation of vanishing bone disease (Gorham’s disease). The ultrastructural localization of non-specific alkaline phosphatase, and of specific and non-specific acid phosphatase activity was studied in slices of tissue removed from a patient with Gorham’s disease. Alkaline phosphatase was present around the plasma membranes of osteoblasts and associated with extracellular matrix vesicles in new woven bone. Concentrations of specific secretory acid phosphatase reaction product in the cytoplasm of degenerating osteoblasts may contribute to the imbalance between bone formation and resorption. Osteoclasts, while few in number, showed non-specific and specific acid phosphatase activity. The Golgi apparatus and heterophagic lysosomes of mononuclear phagocytes were rich in non-specific acid phosphatase. This was also present in the Golgi lamellae and lysosomes of endothelial cells. Acid phosphatase cytochemistry suggests that mononuclear phagocytes, multinuclear osteoclasts, and the vascular endothelium are involved in the process of bone resorption in patients with Gorham’s disease.

Hirayama and colleagues130 have reported on the cellular and humoral mechanisms of osteoclast formation and bone resorption in patients with Gorham-Stout syndrome. These authors suggested that the increase in osteoclast formation in Gorham-Stout syndrome is not due to an increase in the number of circulating osteoclast precursors, but rather to an increase in the sensitivity of these precursors to humoral factors which promote osteoclast formation and bone resorption. It has also been suggested that thyroid C cells and calcitonin may play an important role in the pathogenesis of Gorham’s disease.120

Clinical Features

Gorham’s disease can involve men or women and any age group, although most cases are discovered before the age of 40 years. No familial predisposition has been found. The process may affect the appendicular or the axial skeleton. The shoulder121 , 123 , 126 , 131 and the pelvis48 , 61 , 95 , 103 , 118 , 145 are the most common sites of involvement, however, various locations such as the humerus,5 , 17 , 63 scapula,1 , 22 , 59 , 68 clavicle,1 , 29 , 47 , 59 ribs,22 , 56 , 71 , 110 , 143 sternum, pelvis48 , 61 , 95 , 103 , 118 , 145 and femur55 , 89 , 95 can be affected by Gorham’s disease. The disorder is also known to occur at other sites such as the skull,18 , 26 , 27 , 51 , 92 , 98 , 108 , 112 , 128 , 135 mandible,11 , 12 , 19 , 43 , 66 , 91 , 128 , 147 maxillofacial skeleton,33 , 54 , 58 , 62 , 92 , 98 , 99 , 127 , 128 spine,30 , 32 , 71 , 78 , 88 , 100 , 106 , 110 , 112 , 119 , 122 , 131 , 143 hand,39 , 44 , 114 , 144 and foot.90 Disease of the ribs, scapula, or thoracic vertebrae may lead to the development of chylothorax from direct extension of lymphangiectasia into the pleural cavity or via invasion of the thoracic duct.85 Without surgical intervention, patients with Gorham’s disease who develop chylothorax have a high rate of morbidity and mortality.

Clinical manifestations vary and depend on the affected site. Some patients present with a relatively abrupt onset of pain and swelling in the affected extremity, whereas others present with history of insidious onset of pain, limitation of motion, and progressive weakness in the involved limb. This may be accompanied with soft-tissue weakness and/or atrophy. In some cases, history of significant trauma makes the limb painful, forcing the patients to report their symptoms to their family physician and providing for an early diagnosis of Gorham’s disease.

Although the degree of osseous deformity in patients with Gorham’s disease may become severe, serious complications are infrequent. Paraplegia related to spinal cord involvement may occur in patients who have involvement of vertebrae with resultant osteolysis.4 Thoracic cage, pulmonary, or pleural involvement can lead to compromise of respiratory function and death can ensue. Infection of bone and septic shock, although rare, have also been reported.8

Investigations

The standard laboratory blood tests are usually within normal limits, and are not helpful to make a diagnosis of Gorham’s disease. The serum alkaline phosphatase level may be slightly elevated.

A variety of imaging methods can be used in evaluating patients suspected of having Gorham’s disease. Plain radiographs,6 , 28 , 36 , 71 , 77 , 79 , 116 , 136 , 143 radioisotope bone scans,50 , 79 , 81 , 111 , 116 , 143 computed tomography (CT),71 , 76 , 77 , 79 , 87 , 106 , 143 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)76 , 77 , 87 , 106 , 116 , 138 , 143 have all been used in such evaluations.

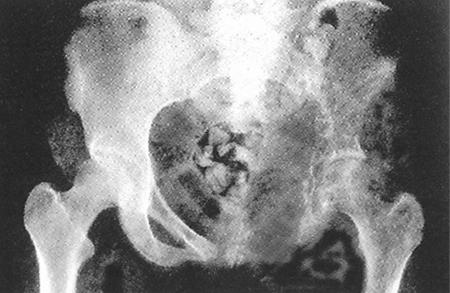

The most dramatic aspect of Gorham’s massive osteolysis is its radiographic appearance. Radiographic findings in patients with Gorham’s disease were described by Resnick.136 During the initial stage of the lesion, radiolucent foci appear in the intramedullary or subcortical regions, resembling findings seen in patchy osteoporosis. Subsequently, slowly progressive atrophy, dissolution, fracture, fragmentation, and disappearance of a portion of the bone occurs with tapering or “pointing” of the remaining osseous tissue and atrophy of soft tissues. The disease process can extend to contiguous bones; the intervening joints afford no protection to extension of the disease. Thus, osteolysis of ilium may be associated with resorption of the proximal portion of the femur (figure 1 ), whereas changes in the scapula may later be combined with osteolysis of the proximal aspect of the humerus, clavicle, and ribs. Such patterns of regional osseous destruction should enable physicians to make an accurate diagnosis. The degree of osseous destruction generally increases relentlessly over a period of years and may, eventually, stabilize spontaneously. Some reports of massive osteolysis describe spontaneous recovery of some of the lost osseous tissue17 or clinical and radiographic improvement after radiation therapy.39

Figure 1.

Antero-posterior radiograph of the pelvis in a patient with Gorham’s disease showing osteolysis involving the left ilium. Note the osseous resorption involving the proximal aspect of the left femur. (Reproduced with permission from Elsevier. In: Peter Bullough, ed. Orthopaedic Pathology. 4th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2004. Figure 7.58, p. 196. Copyright 2004 Elsevier. All rights reserved).

Radioisotope bone scan may demonstrate increased vascularity on initial images and, subsequently, an area of decreased uptake corresponding to the site of diminished or absent osseous tissue. However, these results have been variable.116 The reported MRI findings of Gorham’s osteolysis have also been variable. T1-weighted-spin echo MRIs show uniformly low signal intensity in the involved bones, whereas an increased signal intensity generally is observed in T2-weighted-spin echo images. Enhancement of the lesions is usually seen after intravenous administration of gadolinium.

Differential Diagnoses

It is worth emphasizing that for all patients who present with skeletal osteolysis, a thorough history and meticulous physical examination should be undertaken first. Appropriate blood tests and radiographic studies should be requested to rule out other common (in contrast to the extremely rare Gorham’s disease) underlying causes of osteolysis such as infection, cancer (primary or metastatic), inflammatory or endocrine disorders. The diagnosis of Gorham-Stout syndrome should be suspected or made only after excluding these aforementioned conditions. Figure 2 through figure 5 ▶ ▶ show examples of patients who have benign or malignant (primary or metastatic) bone lesions. It should be noted that radiographic findings of these patients might resemble those of patients with Gorham’s massive osteolysis. Gorham’s disease can also mimick various osteolytic syndromes (table 1 ). Readers are encouraged to refer to major textbooks on radiology of musculoskeletal disorders for details of other primary or idiopathic osteolytic syndromes.

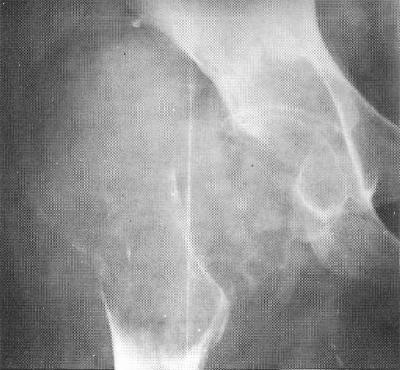

Figure 2.

Plain radiograph of the pelvis of a man, 24 years of age, showing a large, expansile osteolytic lesion and a soft-tissue mass involving the right proximal femur. A diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst was made after biopsy of the lesion (Reproduced with permission. In: Peter Renton, ed. Orthopaedic Radiology: Pattern Recognition and Differential Diagnosis. 1st Ed. London, UK: Martin Dunitz Ltd.; 1990. Figure 3.43b, p. 170. Copyright 1990 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved).

Figure 3.

Plain radiograph in a male, 33 years of age, showing diffuse infiltration along the humeral shaft and osteolysis. There is some reactive sclerosis, no new bone formation and very little evidence of soft-tissue mass. A diagnosis of reticulum cell sarcoma was established on biopsy of the lesion (Reproduced with permission. In: Peter Renton, ed. Orthopaedic Radiology: Pattern Recognition and Differential Diagnosis. 1st Ed. London, UK: Martin Dunitz Ltd.; 1990. Figure 3.76, p. 198. Copyright 1990 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved).

Figure 4.

Plain radiograph of the distal femur of a male, 18 years of age, showing osteolytic lesion with a soft-tissue mass. A diagnosis of osteosarcoma was confirmed on biopsy of the lesion (Reproduced with permission. In: Peter Renton, ed. Orthopaedic Radiology: Pattern Recognition and Differential Diagnosis. 1st Ed. London, UK: Martin Dunitz Ltd.; 1990. Figure 3.68a, p. 190. Copyright 1990 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved).

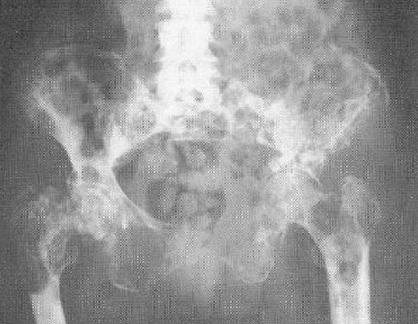

Figure 5.

Plain radiograph of the pelvis of a female patient who has extensive metastatic bone disease secondary to carcinoma of the breast. Note the widespread areas of osteolysis throughout the pelvis and proximal femora. There is also some reactive sclerosis. (Reproduced with permission. In: Peter Renton, ed. Orthopaedic Radiology: Pattern Recognition and Differential Diagnosis. 1st Ed. London, UK: Martin Dunitz Ltd.; 1990. Figure 2.13, p. 86. Copyright 1990 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved).

Treatment

Due to the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standard therapy available. The medical treatment for Gorham’s disease includes radiation therapy,10 , 21 , 39 , 44 , 60 , 69 , 101 , 112 , 139 , 140 anti-osteoclastic medication (bisphosphonates),109 , 146 and alpha-2b interferon.109

The principal treatment modalities are surgery and radiation therapy. Surgical options include resection of the lesion, and reconstruction using bone grafts and/or prostheses. Definitive radiation therapy in moderate doses (40–45 Gy in 2 Gy fractions) appears to result in a good clinical outcome with few long-term complications.69 The prognosis for patients with Gorham’s disease is generally good unless vital structures are involved.

A particularly dangerous form of the disease affects the thorax resulting in pleural effusion29 , 47 , 70 , 71 , 83 , 86 , 93 , 101 , 107 and chylothorax.9 , 20 , 41 , 48 , 56 , 78 , 85 , 96 , 104 , 122 , 129 , 132 – 134 , 137 , 142 Various treatment modalities have been employed for the management of chylothorax in patients with Gorham’s disease, including pleurectomy,35 , 134 pleurodesis,20 , 29 , 48 , 133 , 142 thoracic duct ligation,85 radiation therapy,101 , 133 , 139 , 142 interferon therapy and oral clodronate,109 and bleomycin.96

Tie and colleagues85 have reported some success using thoracic duct ligation to treat chylothorax in patients with Gorham’s disease. Of the eleven cases they reviewed, seven patients underwent successful thoracic duct ligation and survived, while four patients died following failed attempts to localize the thoracic duct during surgery. It is worth emphasizing that thoracic duct ligation does not always produce a lasting resolution of chylothorax.45 , 132

Radiation therapy101 , 133 , 139 , 142 can be employed for the management of chylothorax in patients who may not be suitable candidates for an extensive surgical procedure due to their poor general health, and for those who have failed surgical treatment. The disadvantages of radiation therapy include the possibility of acute side effects such as gastrointestinal tract irritation with resultant nausea and/or vomiting, and radiation-induced pneumonia. Furthermore, in children and adolescents who receive high-dose radiation therapy, the potential for secondary malignancy and growth restriction exists and should be considered before embarking on this mode of treatment.

Discussion

Gorham’s disease is a very rare disorder characterized by uncontrolled, destructive proliferation of vascular or lymphatic capillaries within bone and surrounding soft tissue.2 Most cases occur in children and young adults (usually less than 40 years of age) and no definite inheritance pattern has been reported. Diagnosis is often delayed in most cases as laboratory studies are usually within normal limits. A high index of clinical suspicion together with characteristic radiographic and histopathological findings are helpful for making an early accurate diagnosis.

The natural history of Gorham’s disease is unpredictable and, in some cases, spontaneous regression has been reported.17 , 45 Campbell and colleagues17 reported a case of an elderly woman who presented with a pathological fracture of the right humerus. In this case, progressive dissolution of the shaft of humerus occurred over a period of six months. No cause could be established and the patient refused biopsy. The pathologic humerus was treated with splinting and the humeral shaft gradually reformed and re-ossified over a period of next two years. In many other patients, Gorham’s disease is relentlessly progressive and involvement of vital structures can occur leading to high morbidity and mortality. Extension of the disease from the scapula, ribs or thoracic vertebra can result in pericardial and pleural effusions, and chylothorax. In general, visceral and spinal involvement is usually associated with a poor prognosis.

Several therapeutic modalities have been used in the management of Gorham’s disease. The non-operative options include radiation therapy,10 , 21 , 39 , 44 , 60 , 69 , 101 , 112 , 139 , 140 anti-osteoclastic medication (bisphosphonates),109 , 146 and alpha-2b interferon.109 The operative options include surgical resection,10 , 29 , 63 , 69 reconstruction using a bone graft,30 , 63 or a prosthesis.5 , 42 It is worth noting that the success rate after the use of a bone graft is low. Most surgeons, based on their personal experience, have observed that the bone graft undergoes dissolution. In recent years, most patients have been treated with surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Turra and associates63 have reported a 20-year follow-up of a case of surgically treated massive osteolysis of the humerus that occurred in a male, 19 years of age. The lesion was successfully treated with an autogenous fibular shaft transplant. During the 20-year follow-up period, the function of the humerus was restored. Plain radiographs showed incorporation of the fibular graft without any recurrence of the disease. This report supports the contention that only predominantly cortical autogenous bone grafting may be successful. It seems that the cortical bone (compared to the cancellous bone) shows greater resistance to erosion to the offending lymphangiomatous osteolytic tissue.

Rauh and Gross114 reported a 48-year follow-up of Gorham-Stout disease involving the right hand of a 12-year-old patient. The osteolysis progressed until the age of 21 years and was then stable until the age of 59 years when the patient died from metastatic colon cancer. This case report supports the common belief that Gorham’s disease undergoes spontaneous resolution.

Boyer and colleagues145 have recently reported a 50-year clinical and radiographic follow-up of Gorham-Stout syndrome of the pelvis in a man who has never been treated. To date, this is the longest documented case report of Gorham’s disease and its natural history. This case-report demonstrates that after a variable time of evolution, the massive osteolysis is able to undergo spontaneous arrest and that the lesions may remain stable during several decades. No reossification was observed even after 37 years of disease quiescence.

Conclusions

Gorham’s disease is a rare musculoskeletal disorder. Its diagnosis is usually delayed and often missed as not many physicians have opportunity to treat this rare disease entity in their clinical practice. Review of the published literature on this subject, shows that this disease is described and discussed under a number of eponyms (table 2 ).

Gorham’s disease is a rare, peculiar musculoskeletal disorder in which the affected bone virtually disintegrates and is replaced by vascular fibrous connective tissue. The etiology of Gorham’s disease is still speculative. Its clinical presentation is variable, largely depending upon the site of skeletal involvement. The natural history and prognosis of this disease are unpredictable and no effective therapy is known. In recent years, most patients have been treated with surgery and/or radiation therapy.

Physicians must take a thorough history and perform a complete physical examination for all patients who present with osteolysis of the shoulder or pelvic girdle, long bones, or vertebrae. Other diagnoses, such as infection and cancer, must be ruled out by appropriate blood tests and radiographic studies. A definitive diagnosis must be established by performing a biopsy of the offending lesion. The diagnosis of Gorham’s disease should be made only after carefully eliminating the aforementioned causes of osteolysis.

In this issue of Clinical Medicine & Research, Duffy and colleagues148 report a case of Gorham’s disease with chylothorax that was successfully treated with radiation therapy. The authors should be congratulated for bringing such a rare case to the attention of the medical community and helping to expand upon our poor existing knowledge of this ailment. Awareness of this disease entity should enhance our clinical acumen and allow for better evaluation and management of this fascinating and rare disorder.

References

- 1. Gorham LW, Wright AW, Shultz HH, Maxon FC, Jr. Disappearing bones: a rare form of massive osteolysis: report of two cases, one with autopsy findings. Am J Med 1954;17:674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone): its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1955;37-A:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hambach R, Pujman J, Maly V. Massive osteolysis due to hemangiomatosis: report of a case of Gorham’s disease with autopsy. Radiology 1958;71:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halliday DR, Dahlin DC, Pugh DG, Young HH. Massive osteolysis and angiomatosis. Radiology 1964;82:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poirier H. Massive osteolysis of the humerus treated by resection and prosthetic replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1968;50-B:158–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Torg JS, Steel HH. Sequential roentgenographic changes occurring in massive osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1969;51-A:1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fornasier VL. Haemangiomatosis with massive osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1970; 52:444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kery L, Wouters HW. Massive osteolysis: report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1970;52-B:452–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Touraine R, Bernard JP, Trouillier JP, Balandreau AM. [Chylothorax and Gorham’s disease (or regional massive osteolysis)] [Article in French]. J Fr Med Chir Thorac 1971;25:315–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gutierrez RM, Spjut HJ. Skeletal angiomatosis: report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1972;85:82–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phillips RM, Bush OB Jr, Hall HD. Massive osteolysis (phantom bone, disappearing bone): report of a case with mandibular involvement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1972;34:886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Black MJ, Cassisi NJ, Biller HF. Massive mandibular osteolysis. Arch Otolaryngol 1974;100:314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nozicka Z, Herout V, Fingerland A. [Gorham-Stout syndrome caused by hemangiolymphangioma] [Article in Czech]. Cesk Patol 1974;10:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sage MR, Allen PW. Massive osteolysis: report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1974;56-B:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson JS, Schurman DJ. Massive osteolysis: case report and review of literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1974;103:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watson RC, Melamed MR. Vanishing bone disease. Clin Bull 1974;4:18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campbell J, Almond HG, Johnson R. Massive osteolysis of the humerus with spontaneous recovery. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1975;57-B:238–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iyer V, Nayar A. Massive osteolysis of the skull: case report. J Neurosurg 1975;43:92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cadenat H, Bonnefont J, Barthelemy R, Fabie M, Combelles R. [The phantom mandible] [Article in French]. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac 1976;77:877–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patrick JH. Massive osteolysis complicated by chylothorax successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1976;58-B:347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heyden G, Kindblom LG, Nielsen JM. Disappearing bone disease: a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1977;59-A:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sacristan HD, Portal LF, Castresana FG, Pena DR. Massive osteolysis of the scapula and ribs: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1977;59-A:405–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Catalan A, Ignacio AC. Vanishing bone disease: a case report. Hawaii Med J 1978;37:302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murphy JB, Doku HC, Carter BL. Massive osteolysis: phantom bone disease. J Oral Surg 1978;36:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ross JL, Schinella R, Shenkman L. Massive osteolysis: an unusual cause of bone destruction. Am J Med 1978;65:367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iyer GV. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea from massive osteolysis of the skull. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1979;42:767–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reddy DR, Sathyanarayana K, Reddy VV, Rao DM, Rajyalakshmi K. Massive osteolysis of skull bones. J Indian Med Assoc 1979;72:165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abrahams J, Ganick D, Gilbert E, Wolfson J. Massive osteolysis in an infant. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980;135:1084–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feigl D, Seidel L, Marmor A. Gorham’s disease of the clavicle with bilateral pleural effusions. Chest 1981;79:242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Woodward HR, Chan DP, Lee J. Massive osteolysis of the cervical spine: a case report of bone graft failure. Spine 1981;6:545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gonzalez Ruperez J, Lorenzo JC, Henkes J, Ferrandiz C, Peyri J. [Gorham’s disease] [Article in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr 1982;73(3–4):95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Edwards WH Jr, Thompson RC Jr, Varsa EW. Lymphangiomatosis and massive osteolysis of the cervical spine: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983;177:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frederiksen NL, Wesley RK, Sciubba JJ, Helfrick J. Massive osteolysis of the maxillofacial skeleton: a clinical, radiographic, histologic, and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1983;55:470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, Feeney JE. Perspectives on massive osteolysis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1983;55:331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pedicelli G, Mattia P, Zorzoli AA, Sorrone A, De Martino F, Sciotto V. Gorham syndrome. JAMA 1984;252(11):1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gowin W, Rahmanzadeh R. [Radiologic diagnosis of massive idiopathic osteolysis (Gorham-Stout syndrome)] [Article in German]. Rontgenpraxis 1985;38:128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grabowski MT, Mittelmeier H. [The syndrome of idiopathic Gorham-Stout osteolysis] [Article in Polish]. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol 1985;50:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grabowski MT, Schmitt E, Schmitt O. [2 cases of a rare syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis (Gorham-Stout syndrome] [Article in Polish]. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol 1985;50:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hanly JG, Walsh NM, Bresnihan B. Massive osteolysis in the hand and response to radiotherapy. J Rheumatol 1985;12:580–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G. The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis: classification, review, and case report. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1985;67-B:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown LR, Reiman HM, Rosenow EC 3rd, Gloviczki PM, Divertie MB. Intrathoracic lymphangioma. Mayo Clin Proc 1986;61(11):882–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cannon SR. Massive osteolysis: a review of seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1986; 68-B:24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mathias K, Hoffmann J, Martin K. [Gorham-Stout syndrome of the mandible] [Article in German]. Radiologe 1986;26:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carneiro RS, Steglich V. “Disappearing bone disease” in the hand. J Hand Surg [Am] 1987;12:629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Choma ND, Biscotti CV, Bauer TW, Mehta AC, Licata AA. Gorham’s syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med 1987;83:1151–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dickson GR, Mollan RA, Carr KE. Cytochemical localization of alkaline and acid phosphatase in human vanishing bone disease. Histochemistry 1987;87:569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Feigl D, Marmor A. Gorham’s disease of the clavicle with bilateral pleural effusions: eight years later. Chest 1987;92:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hejgaard N, Olsen PR. Massive Gorham osteolysis of the right hemipelvis complicated by chylothorax: report of a case in a 9-year-old boy successfully treated by pleurodesis. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Joseph J, Bartal E. Disappearing bone disease: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marymont JV. Comparative imaging. Massive osteolysis (Gorham’s syndrome, disappearing bone disease). Clin Nucl Med 1987;12:153–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rao SV, Reddy DR, Reddy GM, Reddy PK, Mohan UL, Reddy M. Idiopathic massive osteolysis of skull bones: a case report. Neurosurgery 1987;21:564–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krzok G, Flossel C. [Gorham-Stout syndrome and diffuse skeletal hemangiomatosis] [Article in German]. Beitr Orthop Traumatol 1988;35:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wohar RM. A call for information on massive osteolysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 46:176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Anavi Y, Sabes WR, Mintz S. Gorham’s disease affecting the maxillofacial skeleton. Head Neck 1989;11:550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mendez AA, Keret D, Robertson W, MacEwen GD. Massive osteolysis of the femur (Gorham’s disease): a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Romero J, Kunz R, Munch U, Neff U. [Successful treatment of a cheilothorax in lymphangiomatosis of the ribs (Gorham-Stout syndrome)] [Article in German]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1989;119:671–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dickson GR, Hamilton A, Hayes D, Carr KE, Davis R, Mollan RA. An investigation of vanishing bone disease. Bone 1990;11:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fisher KL, Pogrel MA. Gorham’s syndrome (massive osteolysis): a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990;48:1222–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Glass-Royal M, Stull MA. Musculoskeletal case of the day: Gorham syndrome of the right clavicle and scapula. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;154:1335–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Handl-Zeller L, Hohenberg G. Radiotherapy of Morbus Gorham-Stout: the biological value of low irradiation dose. Br J Radiol 1990;63(747):206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kulenkampff HA, Richter GM, Hasse WE, Adler CP. Massive pelvic osteolysis in the Gorham-Stout syndrome. Int Orthop 1990;14:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ohya T, Shibata S, Takeda Y. Massive osteolysis of the maxillofacial bones: report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990;70:698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Turra S, Gigante C, Scapinelli R. A 20-year follow-up study of a case of surgically treated massive osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;250:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Friedman L, Horwitz T, Beck M, Sinn R. Case report 672: Gorham’s disease. Skeletal Radiol 1991;20:307–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zarrouk H, Dowlati A, Dowlati Y, Pierard GE. [What is your diagnosis? Osteolytic hemangiomatosis or Gorham’s disease] [Article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1991;118:727–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Freedy RM, Bell KA. Massive osteolysis (Gorham’s disease) of the temporomandibular joint. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992;101:1018–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tauro B. Multicentric Gorham’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1992;74-B:928–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Damron TA, Brodke DS, Heiner JP, Swan JS, DeSouky S. Case report 803: Gorham’s disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome) of scapula. Skeletal Radiol 1993;22:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dunbar SF, Rosenberg A, Mankin H, Rosenthal D, Suit HD. Gorham’s massive osteolysis: the role of radiation therapy and a review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993;26:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Meller JL, Curet-Scott M, Dawson P, Besser AS, Shermeta DW. Massive osteolysis of the chest in children: an unusual cause of respiratory distress. J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:1539–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mitchell CS, Parisi MT, Osborn RE. Gorham’s disease involving the thoracic skeleton: plain films and CT in two cases. Pediatr Radiol 1993;23:543–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schiel H, Prein J. Seven-year follow-up of vanishing bone disease in a 14-year-old girl. Head Neck 1993;15:352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schnall SB, Vowels J, Schwinn CP, Wong D. Disappearing bone disease of the upper extremity. Orthop Rev 1993;22:617–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shives TC, Beabout JW, Unni KK. Massive osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;294:267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Velez A, Herrera M, Del Rio E, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Gorham’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol 1993;32:884–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Assoun J, Richardi G, Railhac JJ, Le Guennec P, Caulier M, Dromer C, Sixou L, Fournie B, Mansat M, Durroux D. CT and MRI of massive osteolysis of Gorham. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1994;18:981–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dominguez R, Washowich TL. Gorham’s disease or vanishing bone disease: plain film, CT, and MRI findings of two cases. Pediatr Radiol 1994;24:316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Drewry GR, Sutterlin CE 3rd, Martinez CR, Brantley SG. Gorham disease of the spine. Spine 1994;19:2213–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Igel BJ, Shah H, Williamson MR, Sell JJ. Gorham’s syndrome: correlative imaging using nuclear medicine, plain film, and 3-D CT. Clin Nucl Med 1994;19:1017–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kareem BA, Das PK, Saad R. Disappearing bone disease: a case report. Singapore Med J 1994;35:527–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kobayashi H, Shigeno C, Sakahara H, Hosono M, Hosono M, Yao ZS, Endo K, Konishi J. Intraosseous hemangiomatosis: technetium-99m(V)dimercaptosuccinic acid and technetium-99m-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate imaging. J Nucl Med 1994;35:1482–1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mangar D, Murtha PA, Aquilina TC, Connell GR. Anesthesia for a patient with Gorham’s syndrome: “disappearing bone disease”. Anesthesiology 1994;80:466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Padua y Gabriel A, Peraza-Martinez L, Peralta-Sanchez J, Jaramillo Y, Arista-Nasr J. [Gorham’s disease: report of 2 cases associated with bilateral pleural effusion] [Article in Spanish]. Rev Invest Clin 1994;46:301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Prabhu SS, Colaco MP, Pradhan MR, Johari AN, Devany G. Massive osteolysis -Gorham’s syndrome. Indian Pediatr 1994;31:1542–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tie ML, Poland GA, Rosenow EC 3rd. Chylothorax in Gorham’s syndrome: a common complication of a rare disease. Chest 1994;105:208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tie ML, Poland GA, Rosenow EC 3rd. Pleural effusion: a complication of Gorham’s disease. Pediatr Radiol 1994;24:542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Vinee P, Tanyu MO, Hauenstein KH, Sigmund G, Stover B, Adler CP. CT and MRI of Gorham syndrome. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1994;18:985–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Foult H, Goupille P, Aesch B, Valat JP, Burdin P, Jan M. Massive osteolysis of the cervical spine: a case report. Spine 1995;20:1636–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Giraudet-Le Quintrec JS, Peyrache MD, Courpied JP, Menkes CJ, Kerboull M. [Idiopathic massive osteolysis of the femur: syndrome called Gorham-Stout syndrome] [Article in French]. Presse Med 1995;24(15):719–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Green HD, Mollica AJ, Karuza AS. Gorham’s disease: a literature review and case reports. J Foot Ankle Surg 1995;34:435–441. Published erratum appears in J Foot Ankle Surg 1995;34:598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kayada Y, Yoshiga K, Takada K, Tanimoto K. Massive osteolysis of the mandible with subsequent obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;53:1463–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Moore MH, Lam LK, Ho CM. Massive craniofacial osteolysis. J Craniofac Surg 1995;6:332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ng SE, Wang YT. Gorham’s syndrome with pleural effusion and colonic carcinoma. Singapore Med J 1995;36:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rudert M, Gross W, Kirschner P. [Gorham-Stout massive osteolysis: a case report] [Article in German]. Unfallchirurg 1995;98:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Stove J, Reichelt A. Massive osteolysis of the pelvis, femur and sacral bone with a Gorham-Stout syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1995;114:207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Aoki M, Kato F, Saito H, Mimatsu K, Iwata H. Successful treatment of chylothorax by bleomycin for Gorham’s disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;330:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Devlin RD, Bone HG 3rd, Roodman GD. Interleukin-6: a potential mediator of the massive osteolysis in patients with Gorham-Stout disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:1893–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Diaz-Ramon C, Fernandez-Latorre F, Revert-Ventura A, Mas-Estelles F, Domenech-Iglesias A, Lazaro-Ventura A. Idiopathic progressive osteolysis of craniofacial bones. Skeletal Radiol 1996;25:294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Klein M, Metelmann HR, Gross U. Massive osteolysis (Gorham-Stout syndrome) in the maxillofacial region: an unusual manifestation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;25:376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Livesley PJ, Saifuddin A, Webb PJ, Mitchell N, Ramani P. Gorham’s disease of the spine. Skeletal Radiol 1996;25:403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. McNeil KD, Fong KM, Walker QJ, Jessup P, Zimmerman PV. Gorham’s syndrome: a usually fatal cause of pleural effusion treated successfully with radiotherapy. Thorax 1996;51:1275–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Needleman RL. Gorham’s disease: a literature review and case reports. J Foot Ankle Surg 1996;35:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Nemec B, Matovinovic D, Gulan G, Kozic S, Schnurrer T. Idiopathic osteolysis of the acetabulum: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1996;78-B:666–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Riantawan P, Tansupasawasdikul S, Subhannachart P. Bilateral chylothorax complicating massive osteolysis (Gorham’s syndrome). Thorax 1996;51:1277–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wilkinson IB, Kinnear WJ. Young patient with Gorham’s syndrome. Thorax 1996;51:1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Chung C, Yu JS, Resnick D, Vaughan LM, Haghighi P. Gorham syndrome of the thorax and cervical spine: CT and MRI findings. Skeletal Radiol 1997;26:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Dutheil-Doco A, Ducou le Pointe H, Larroquet M, Josset P, Tournier G, Montagne JP. [Gorham disease with prominent pleuropulmonary manifestation] [Article in French]. J Radiol 1997;78:665–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Frankel DG, Lewin JS, Cohen B. Massive osteolysis of the skull base. Pediatr Radiol 1997;27:265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Astrom G. Alpha-2b interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet 1997;350(9094):1822–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Leonard JC, Morin C. [Radiological case of the month: Gorham disease of costovertebral localization] [Article in French]. Arch Pediatr 1997;4:893–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Mabille L, Berenger N, Laredo JD, Kuntz D, Mundler O. Vanishing vertebra. Clin Nucl Med 1997;22:49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Mawk JR, Obukhov SK, Nichols WD, Wynne TD, Odell JM, Urman SM. Successful conservative management of Gorham disease of the skull base and cervical spine. Childs Nerv Syst 1997;13:622–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Pazzaglia UE, Andrini L, Bonato M, Leutner M. Pathology of disappearing bone disease: a case report with immunohistochemical study. Int Orthop 1997;21:303–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Rauh G, Gross M. Disappearing bone disease (Gorham-stout disease): report of a case with a follow-up of 48 years. Eur J Med Res 1997;2:425–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sato K, Sugiura H, Yamamura S, Mieno T, Nagasaka T, Nakashima N. Gorham massive osteolysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1997;116:510–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Spieth ME, Greenspan A, Forrester DM, Ansari AN, Kimura RL, Gleason-Jordan I. Gorham’s disease of the radius: radiographic, scintigraphic, and MRI findings with pathologic correlation. A case report and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol 1997;26:659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Auge B, Toussirot E, Kantelip B, Wendling D. From polycystic bone angiomatosis to Gorham’s disease: two case-reports and literature review. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1998;65:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Dan’ura T, Ozaki T, Sugihara S, Taguchi K, Inoue H. Massive osteolysis in the pelvis - a case report. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69:197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Florchinger A, Bottger E, Claass-Bottger F, Georgi M, Harms J. [Gorham-Stout syndrome of the spine: case report and review of the literature] [Article in German]. Rofo 1998;168:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Korsic M, Jelasic D, Potocki K, Giljevic Z, Aganovic I. Massive osteolysis in a girl with agenesis of thyroid C cells. Skeletal Radiol 1998;27:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Remia LF, Richolt J, Buckley KM, Donovan MJ, Gebhardt MC. Pain and weakness of the shoulder in a 16-year-old boy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998;347:268–271, 287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Grelet V, Chataigner H, Onimus M. [Spinal localization of Gorham’s syndrome: case report] [Article in French]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1999;85:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Hofbauer LC, Klassen RA, Khosla S. Gorham-Stout disease (phantom bone) of the shoulder girdle. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:904–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Moller G, Gruber H, Priemel M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. [Gorham-Stout idiopathic osteolysis - a local osteoclastic hyperactivity?] [Article in German]. Pathologe 1999;20:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Moller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G. The Gorham-Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis): a report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1999;81-B:501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Pans S, Simon JP, Dierickx C. Massive osteolysis of the shoulder (Gorham-Stout syndrome). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999;8:281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Holroyd I, Dillon M, Roberts GJ. Gorham’s disease: a case (including dental presentation) of vanishing bone disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Oujilal A, Lazrak A, Benhalima H, Boulaich M, Amarti A, Saidi A, Kzadri M. [Massive lytic osteodystrophy or Gorham-Stout disease of the craniomaxillofacial area] [Article in French]. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2000;121:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Chavanis N, Chaffanjon P, Frey G, Vottero G, Brichon PY. Chylothorax complicating Gorham’s disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:937–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Hirayama T, Sabokbar A, Itonaga I, Watt-Smith S, Athanasou NA. Cellular and humoral mechanisms of osteoclast formation and bone resorption in Gorham-Stout disease. J Pathol 2001;195:624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Bode-Lesniewska B, von Hochstetter A, Exner GU, Hodler J. Gorham-Stout disease of the shoulder girdle and cervico-thoracic spine: fatal course in a 65-year-old woman. Skeletal Radiol 2002;31:724–729. Epub 2002 Sep 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Fujiu K, Kanno R, Suzuki H, Nakamura N, Gotoh M. Chylothorax associated with massive osteolysis (Gorham’s syndrome). Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1956–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Lee WS, Kim SH, Kim I, Kim HK, Lee KS, Lee SY, Heo DS, Jang BS, Bang YJ, Kim NK. Chylothorax in Gorham’s disease. J Korean Med Sci 2002;17:826–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Miller GG. Treatment of chylothorax in Gorham’s disease: case report and literature review. Can J Surg 2002;45:381–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Plontke S, Koitschev A, Ernemann U, Pressler H, Zimmermann R, Plasswilm L. [Massive Gorham-Stout osteolysis of the temporal bone and the craniocervical transition] [Article in German]. HNO 2002;50:354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Resnick D. Chapter 89. Osteolysis and chondrolysis. In: Resnick D, ed. Diagnosis of Bone and Joint Disorders. Fourth Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.: W.B. Saunders Company; 2002. Volume 5. pages 4920–4944.

- 137. Yoo SY, Goo JM, Im JG. Mediastinal lymphangioma and chylothorax: thoracic involvement of Gorham’s disease. Korean J Radiol 2002;3:130–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Yoo SY, Hong SH, Chung HW, Choi JA, Kim CJ, Kang HS. MRI of Gorham’s disease: findings in two cases. Skeletal Radiol 2002;31:301–306. Epub 2002 Mar 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Fontanesi J. Radiation therapy in the treatment of Gorham disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2003;25:816–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:1340–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Ricalde P, Ord RA, Sun CC. Vanishing bone disease in a five year old: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;32:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Swelstad MR, Frumiento C, Garry-McCoy A, Agni R, Weigel TL. Chylotamponade: an unusual presentation of Gorham’s syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1650–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Ceroni D, De Coulon G, Regusci M, Kaelin A. Gorham-Stout disease of costo-vertebral localization: radiographic, scintigraphic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Acta Radiol 2004;45:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Lehnhardt M, Steinau HU, Homann HH, Steinstraesser L, Druecke D. [Gorham-Stout disease: report of a case affecting the right hand with a follow-up of 24 years] [Article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 2004;36:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Boyer P, Bourgeois P, Boyer O, Catonne Y, Saillant G. Massive Gorham-Stout syndrome of the pelvis. Clin Rheumatol 2005. April 13: [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 146. Hammer F, Kenn W, Wesselmann U, Hofbauer LC, Delling G, Allolio B, Arlt W. Gorham-Stout disease - stabilization during bisphosphonate treatment. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:350–353. Epub 2004 Nov 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Paley MD, Lloyd CJ, Penfold CN. Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham-Stout syndrome). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;43:166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Duffy BM, Manon R, Patel RR, Welsh JS. A Case of Gorham’s Disease with Chylothorax Treated Curatively with Radiation Therapy. Clinical Medicine & Research 2004;3:83–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]