ABSTRACT

The composition of the respiratory tract microbiome is a notable predictor of infection-related morbidities and mortalities among both adults and children. Species of Corynebacterium, which are largely present as commensals in the upper airway and other body sites, are associated with lower colonization rates of opportunistic bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus. In this study, Corynebacterium-mediated protective effects against S. pneumoniae and S. aureus were directly compared using in vivo and in vitro models. Pre-exposure to Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum reduced the ability of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae to infect the lungs of mice, indicating a broadly protective effect. Adherence of both pathogens to human respiratory tract epithelial cells was significantly impaired following pre-exposure to C. pseudodiphtheriticum or Corynebacterium accolens, and this effect was dependent on live Corynebacterium colonizing the epithelial cells. However, Corynebacterium-secreted factors had distinct effects on each pathogen. Corynebacterium lipase activity was bactericidal against S. pneumoniae, but not S. aureus. Instead, the hemolytic activity of pore-forming toxins produced by S. aureus was directly blocked by a novel Corynebacterium-secreted factor with protease activity. Taken together, these results suggest diverse mechanisms by which Corynebacterium contribute to the protective effect of the airway microbiome against opportunistic bacterial pathogens.

KEYWORDS: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Corynebacterium, respiratory tract infection, epithelial cells, hemolysins, adherence, microbial interactions

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus are the predominant bacterial pathogens of the respiratory tract. S. pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe associated with a wide range of infections including pneumonia, bacteremia, otitis media, meningitis, and sinusitis (1). It is estimated that pneumonia accounts for 22% of all deaths in children aged 1 to 5 years (2) with S. pneumoniae identified as the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia (3). S. pneumoniae colonizes the nasopharynx at variable rates among different populations, ranging from 5% to 70% worldwide, often functioning as a commensal with no physiological presentation (4). However, colonization in the upper airway is an important precursor of lower airway infection. S. aureus is another Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacterium that causes a wide range of clinical diseases. S. aureus asymptomatically colonizes the anterior nares of 20%–30% of the population (5), with carriers at increased risk for distal infections including skin and soft tissue infections, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, urinary tract infections, device-associated infections, and bacterial pneumonia. S. pneumoniae and S. aureus are also leading causes of secondary bacterial infection, which is associated with poorer clinical outcomes in patients with viral pneumonia (6, 7).

While antibiotics have proven effective since their widespread introduction in the 1940s, antibiotic resistance among pneumococcal and S. aureus infections has been rising in recent decades. Resistance to one or more antibiotics has been identified for around 30% of S. pneumoniae infections (8). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections and is associated with higher mortality due to treatment difficulty (9). There is currently no vaccine for S. aureus, limiting prevention to basic strategies such as hygiene and contact prevention along with anti-infectives (10). While the most recent iterations of pneumococcal vaccines target up to 23 serotypes of S. pneumoniae, the vast majority of the over 100 serotypes in circulation remain outside vaccine coverage. These difficulties underscore the need for new treatment and prevention strategies to limit the clinical burden of bacterial pneumonia.

The airway microbiome inhabiting the upper respiratory tract is one of the first lines of defense against pathogens including S. pneumoniae and S. aureus. Recently, Corynebacterium species have emerged as an important component of the beneficial impact of the airway microbiome against colonization and infection with respiratory tract pathogens (11). The presence of Corynebacterium in the upper airway is correlated with reduced Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization and the promotion of a more stable airway microbiome (12–16). Longitudinal studies in young children have revealed that a greater abundance of Corynebacterium is predictive of lower infection risk (17–20). Inoculation of Corynebacterium into the nares of human volunteers resulted in a significant reduction in S. aureus colonization (21), demonstrating as a proof-of-principle that Corynebacterium species can interfere with S. aureus colonization. The species Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum and Corynebacterium accolens have protective phenotypes in several models. In mice, pre-exposure to C. pseudodiphtheriticum reduced S. pneumoniae lung burdens in a viral co-infection model (22), and pre-exposure to C. accolens reduced S. pneumoniae colonization and lower airway infection (23). However, there is also evidence for species-specific effects of Corynebacterium isolates. In one study, C. pseudodiphtheriticum was negatively correlated with S. aureus carriage and reduced S. aureus growth on agar plates, while C. accolens had the opposite effect (15). In contrast, several nasal C. accolens isolates impaired S. aureus growth on agar plates and reduced S. aureus virulence in a worm infection model (24, 25). While these studies corroborate the inhibitory potential of Corynebacterium against S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, the mechanisms mediating Corynebacterium protective effects are still largely unknown and the species-specific effects on S. pneumoniae versus S. aureus remain unclear.

Here, we used a mouse infection model and several in vitro systems to interrogate the effects of Corynebacterium species against S. pneumoniae and S. aureus in parallel. Our findings identify Corynebacterium isolates with broad inhibitory effects against both pathogens in the context of lung infection and adherence to human respiratory tract epithelial cells, with distinct secreted factors contributing to pathogen-specific interference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Corynebacterium isolates were grown from glycerol stocks on BHI agar plates (BD Difco Bacto Brain Heart Infusion, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1% Tween 80 (polysorbate, VWR) aerobically at 37°C overnight. From agar plates, colonies were used to inoculate BHI + 1% Tween 80 liquid cultures which were grown aerobically for 18 hours at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. When indicated, 180 mg/mL of triolein was added to agar plates or as specified to liquid media cultures. Heat-killed (HK) Corynebacterium was prepared by resuspending pelleted bacteria from liquid cultures in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), washing three times in PBS, and incubating for 30 minutes at 65°C. Bacterial killing was confirmed by the absence of growth on agar plates.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strainsc

| Strain | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae | ||

| S. pneumoniae D39 | rspL streptomycin resistant | (26) |

| S. pneumoniae R6 | Unencapsulated | (27) |

| S. aureus | ||

| S. aureus USA300 (AH1263) | MRSAa | (28) |

| S. aureusΔfnbAB (AH4392) | fnbAB mutant of USA300 | (29) |

| S. aureusΔagr (AH1292) | agr mutant of USA300 | (30) |

| S. aureusΔhla (AH1589) | hla mutant of USA300 | (31) |

| Corynebacterium | ||

| C. pseudodiphtheriticum DSM 44287 | Leibniz Institute, DSMZ | |

| C. accolens ATCC 49726 | ATCCb | |

| C. accolens KPL1818 | Human nasal isolate | (32) |

| C. accolens KPL1818Δlips1 (KPL2503) | lips1 mutant of KPL1818 | (32) |

| C. accolens KPL1818compl (KPL2505) | Complemented lips1 mutant | (32) |

| C. accolens DSM 44278 | Leibniz Institute, DSMZ | |

| C. accolens DSM 44279 | Leibniz Institute, DSMZ | |

| C. striatum DSM 20668 | Leibniz Institute, DSMZ | |

| C. amycolatum SK46 BEI HM-109 | BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Shaded rows denote each species or genus used in the study.

S. pneumoniae strains were cultured from frozen glycerol stocks in Todd Hewitt Broth with 5% Yeast Extract (BD Bacto) at 37°C with 5% CO2 to mid-log phase. For agar plates, tryptic soy broth (TSB, MP Biomedicals) was supplemented with 5 µg/mL of neomycin and 5,000 units/plate of fresh catalase (Worthington Biomedical Corporation), and plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 18 hours. Media was supplemented with 50 µg/mL streptomycin (MilliporeSigma) for the streptomycin-resistant variant of strain D39. S. aureus strains were cultured from frozen glycerol stocks on mannitol salt agar (Thermo Scientific Oxoid) for 18 hours at 37°C. Bacteria from agar plates were used to inoculate BHI liquid media and cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm to mid-log phase.

Mouse infection

Male and female C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice aged 6–12 weeks old were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664). Prior to infection, mice were treated with an antibiotic cocktail (ampicillin 1 g/L, neomycin 1 g/L, metronidazole 1 g/L, and vancomycin 0.5 g/L, MilliporeSigma and McKesson) ad libitum for 14 days, with a 48-hour rest on regular water prior to C. pseudodiphtheriticum exposures. All infections were performed intranasally under inhaled isoflurane anesthesia with doses of 107–108 colony forming units (CFUs)/mouse, as indicated. C. pseudodiphtheriticum was prepared for infection as pellets re-suspended in 25 µL of cell-free conditioned media (CFCM), described below. Mice were exposed to two consecutive doses of C. pseudodiphtheriticum at 24-hour intervals, with the final exposure occurring 24 hours prior to pathogen infection. S. aureus and S. pneumoniae were prepared as pellets re-suspended in 25 µL of PBS. Mice were sacrificed 24 hours post-infection (hpi) with S. aureus or S. pneumoniae and nasal lavages and bronchoalveolar lavages, and lungs were collected. Nasal lavages were performed by instillation of 200 µL PBS with a cannulated trachea through the nasal cavity and collected from the nares. Bronchoalveolar lavage was collected through cannulated tracheas in 1 mL 1× PBS. Lungs were homogenized in 1× PBS using a Bullet Blender tissue homogenizer (Stellar Scientific, Baltimore, MD). Lung homogenates were centrifuged for 30 seconds at 500 × g prior to serial dilution and plating on selective agar media. CFU burdens in the lungs are reported as a combined measure of bronchoalveolar lavage and lung tissue homogenate burdens.

CFCM plate assays

Corynebacterium were grown on BHI + 1% Tween 80 agar plates supplemented with or without triolein spread on plates as a 180 mg/mL emulsion in 70% ethanol. Inoculated plates were incubated 18 hours under aerobic conditions at 37°C. Liquid cultures prepared from plates were grown in BHI + 1% Tween 80 broth with and without 45 mg/mL triolein and grown 18 hours at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. CFCM was prepared from supernatants of overnight liquid cultures following centrifugation at ≥20,000 × g for 10 minutes and 0.22 µm filtration. CFCM was spread as 200 µL/plate.

Epithelial cell adherence assays

The human lung epithelial cell line A549 and pharyngeal epithelial cell line D562 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Epithelial cells were cultured in Ham’s F-12K (Life Technologies Corporation) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; CPS serum) and 1× penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies Corp.) at 37°C with 5% CO2. For adherence assays, 2 × 105 cells/well were seeded into 24-well culture plates 48 hours prior to infection in Ham’s F-12K media with 10% FBS without antibiotics. At 48 hours, cells were washed once with 1× PBS, twice with HBSS(-) (Life Technologies Corp.), and cultured in Ham’s F-12K media with 10% FBS without antibiotics. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was determined based on epithelial cell counts obtained following treatment with trypsin-EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5–6 minutes at 37°C with 5% CO2 and quantification on a hemocytometer following the addition of Trypan Blue to exclude dead cells (Acros Organics). After addition of Corynebacterium at the indicated MOI, plates were centrifuged for 3 minutes at 1,000 × g to support bacterial adherence and plates were incubated 18 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. At 18 hours, S. pneumoniae strain R6 or S. aureus was added as a PBS cell suspension at the indicated MOI and plates were centrifuged for 3 minutes at 1,000 × g. Following 1-hour infection at 37°C with 5% CO2, media was aspirated and cells were washed 3× with HBSS(-) and 1× with PBS. Cells were lysed following trypsin-EDTA digestion for 15 minutes at 37°C with 5% CO2, after which 300 µL of Milli-Q water was added to each well and mixed thoroughly to suspend bacteria. CFUs were enumerated from cell suspensions following serial dilution and plating on selective agar media. Percent adherence was calculated relative to CFUs obtained from media controls consisting of wells without epithelial cells. Normalized percent adherence was calculated relative to pathogen adherence in untreated wells not colonized with Corynebacterium. Percent cytotoxicity was evaluated by measurement of lactate dehydrogenase release in culture supernatants using a Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical).

Hemolysis assays

For the zone of clearance (ZOC) hemolysis assay, 200 µL of CFCM was spread onto Columbia Blood Agar plates (BBL Columbia CNA Agar w/ 5% sheep blood, BD) and allowed to dry completely. Serial dilutions of S. aureus liquid cultures were spread onto plates in 20 µL spots to facilitate quantification of individual colony zones of hemolysis. Photos taken at 18 hours with a reference ruler were used to calculate ZOC in Adobe Photoshop CC, 2024. For the human blood hemolysis assay, whole blood collected from healthy adults was used to purify red blood cells (RBCs) by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes. CFCM was prepared from S. aureus and Corynebacterium liquid cultures, as described above. Reaction mixtures consisted of 75 µL of CFCM, 25 µL TSB, 100 µL 2× HA buffer (8.5 mL 10% NaCl, 2 mL 1M CaCl2, and 39.5 mL sterile water), and 25 µL RBCs diluted 1:5 in PBS. Tubes were gently inverted to mix and placed on a tube rotator a 37°C. At each experimental time point, tubes were removed and spun at 5,000 × g for 1 minute to pellet intact RBCs. Supernatants were used to measure absorbance at OD543. Heat-treated Corynebacterium CFCM was prepared by incubation at 100°C for 30 minutes. For protease inhibition, 50 µL protease inhibitor (Halt Protease Inhibitor Single-Use Cocktail, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to CFCM. Control CFCM was treated with equivalent volume of dimethylsulfoxide, DMSO (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (version 10, GraphPad Software LLC, San Diego, CA) was used to complete graphing and statistical analyses. Statistical tests included the Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate based on the number of group comparisons. Mann-Whitney U-tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for CFU data, which had non-normal (Gaussian) distribution due to the limit of detection cut-off. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

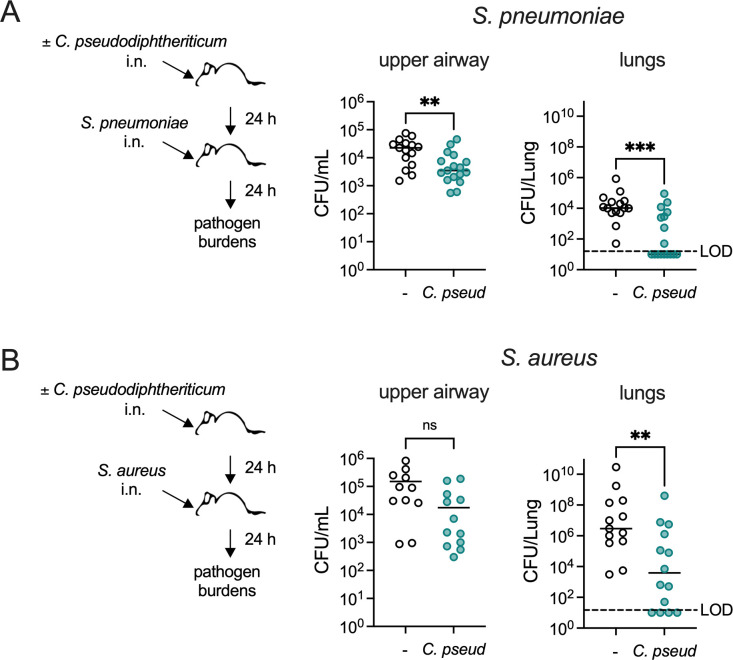

C. pseudodiphtheriticum protects against airway pathogen infection

To directly compare the impact of C. pseudodiphtheriticum on susceptibility to infection with S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, we used a murine respiratory tract infection model developed in prior work (23). In accordance with this model, C57BL/6J wild-type mice were treated with antibiotics for 2 weeks to facilitate Corynebacterium colonization (23). Antibiotic-treated mice were intranasally inoculated with C. pseudodiphtheriticum 24 hours prior to intranasal infection with either encapsulated serotype 2 S. pneumoniae strain D39 or USA300 MRSA S. aureus strain LAC. S. aureus and S. pneumoniae burdens were quantified as CFUs in nasal lavage fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and lung tissue homogenates collected 24 hours post-infection. S. pneumoniae burdens in the upper and lower airways were significantly reduced in mice pre-exposed to C. pseudodiphtheriticum (Fig. 1A), indicating that C. pseudodiphtheriticum provides a protective effect against S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization and lung infection. Similarly, S. aureus burdens were lower in mice pre-exposed to C. pseudodiphtheriticum, with a significant reduction in the lungs (Fig. 1B). Burdens in the lower airway at this early time point are a consequence of both bacterial aspiration to the lungs during intranasal infection and invasion to the lungs following upper airway colonization. In the lungs, 53% of the mice pre-exposed to Corynebacterium had no detectable infection with S. pneumoniae, compared to 0% of mice without Corynebacterium pre-exposure, indicating an improvement in either preventing the establishment of pneumococcal lung infection or in clearance of the infection. Corynebacterium also reduced acquisition of S. aureus lung infection, as 21% of mice pre-exposed to C. pseudodiphtheriticum had no detectable infection compared with 0% in the group without Corynebacterium pre-exposure. Taken together, these results suggest that C. pseudodiphtheriticum has a dual protective effect against respiratory tract infection with S. pneumoniae and S. aureus.

Fig 1.

Exposure to C. pseudodiphtheriticum reduces S. pneumoniae and S. aureus respiratory tract infection. (A) Burdens of S. pneumoniae type 2 strain D39 detected in mice at 24 hours post-infection with 107 CFU/mouse i.n., with or without pre-exposure to 107 CFU/mouse C. pseudodiphtheriticum (C. pseud) i.n. Mice were treated with antibiotics for 2 weeks prior to bacterial exposures. Upper airway CFUs were enumerated from nasopharyngeal lavage fluid. Lung CFUs were the total detected from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and lung tissue. (B) Burdens of S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 detected in mice treated as in (A) at 24 hours post-infection with 108 CFU/mouse i.n. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test. Data are pooled from three independent experiments with n = 15–17 mice/group (A) or n = 13–14 mice/group (B). LOD indicates the limit of detection for CFUs.

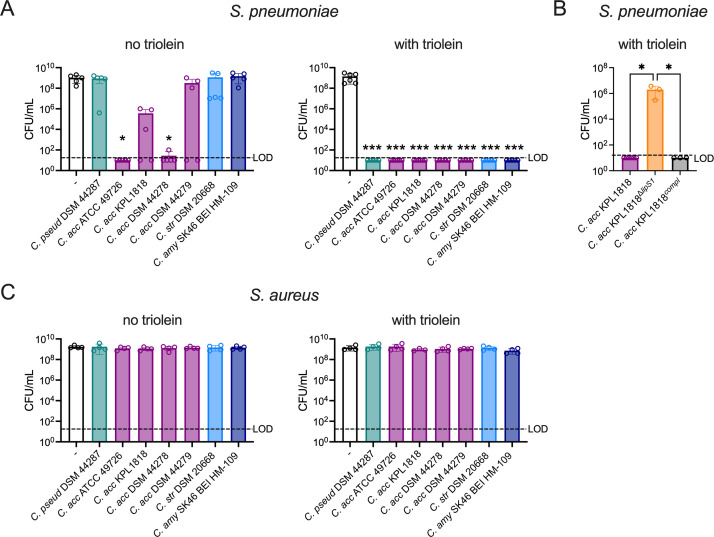

Corynebacterium-secreted lipase selectively inhibits S. pneumoniae

Lipases and esterases secreted by Corynebacterium species mediate direct inhibition of S. pneumoniae growth through the production of bactericidal free fatty acids following cleavage of host lipids (23, 32). In C. accolens, the lipase LipS1 is required for S. pneumoniae inhibition in the presence of triolein, a naturally occurring triacylglycerol (32). LipS1 partially contributed to reduced S. pneumoniae infection following C. accolens pre-exposure in a mouse lung infection model (23). To better understand the relationship between the availability of exogenous lipids and pneumococcal inhibition, a range of Corynebacterium isolates was surveyed for their effect on S. pneumoniae growth using CFCM. When supplemental lipid was limited to the 1% Tween 80 in growth media, Corynebacterium isolates showed a range of pneumococcal growth inhibition (Fig. 2A). Among these, CFCM from two different C. accolens strains completely inhibited S. pneumoniae growth. In contrast, CFCM isolated from strains grown in media supplemented with triolein and 1% Tween 80 conferred complete inhibition of S. pneumoniae growth for all isolates tested, which included one C. pseudodiphtheriticum isolate, four C. accolens isolates, one isolate of Corynebacterium striatum, and one isolate of Corynebacterium amycolatum (Fig. 2A). C. accolens restriction of S. pneumoniae growth in the presence of triolein was dependent on LipS1, as previously reported (32), based on the recovery of S. pneumoniae growth following exposure to CFCM from LipS1-deficient C. accolensΔlips1, but not in CFCM from the complemented strain (Fig. 2B). As Corynebacterium clinical isolates are frequently tested for pathogen-inhibitory capacity, these data suggest that the inclusion of exogenous triolein is critical to capture the full spectrum of S. pneumoniae growth inhibition.

Fig 2.

Corynebacterium-secreted lipase inhibits S. pneumoniae growth without affecting S. aureus. (A) Growth of S. pneumoniae type 2 strain D39 detected on tryptic soy broth agar following pre-spreading plates with supernatants from C. pseudodiphtheriticum (C. pseud DSM 44287), C. accolens (C. acc ATCC 49726, C. acc KPL1818, C. acc DSM 44278, C. acc DSM 44279), C. striatum (C. str), or C. amycolatum (C. amy) strains as indicated grown with 1% Tween 80 alone (no triolein) or supplemented with 180 mg/mL triolein (with triolein). (B) Growth of S. pneumoniae as for (A) following pre-spreading plates with supernatants from C. accolens WT (C. acc KPL1818), a C. accolens mutant deficient in lipS1 (C. acc KPL1818ΔlipS1), or a lipS1 complemented strain (C. acc KPL1818compl) grown with 1% Tween 80 and supplemented with triolein. (C) Growth of S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 detected on mannitol salt agar as in (A). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc analysis. Data are pooled from three to four independent experiments. LOD indicates the limit of detection.

While Corynebacterium species have also been reported to reduce S. aureus growth on agar plates (15, 24, 33), it is unclear whether secreted lipase and/or esterase activity contributes to this phenotype. Using an identical experimental setup as for S. pneumoniae, we found that none of the Corynebacterium isolates tested inhibited S. aureus growth, regardless of triolein supplementation (Fig. 2C). These findings suggest that secreted lipid catabolizing enzymes in Corynebacterium species selectively inhibit growth of S. pneumoniae, but not S. aureus.

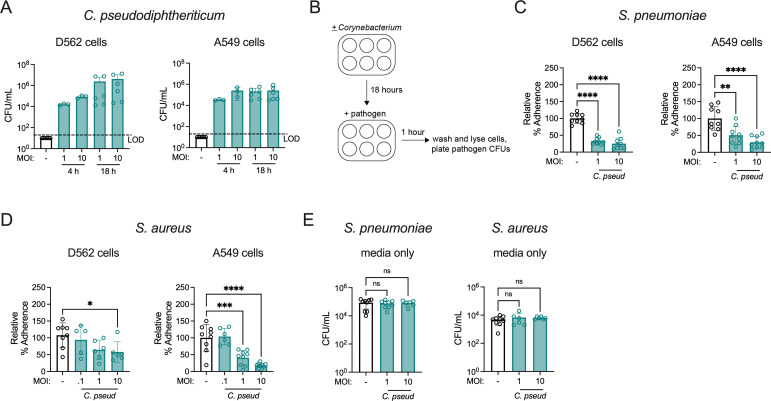

C. pseudodiphtheriticum reduces pathogen adherence to human respiratory tract epithelial cells

Given the inhibitory effect of C. pseudodiphtheriticum against both S. aureus and S. pneumoniae infection in vivo, we next addressed whether Corynebacterium colonization has a similarly broad impact on pathogen adherence to human respiratory tract epithelial cells. The pharyngeal cell line D562 and lung alveolar cell line A549 are well-established models for investigation of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus adherence to the airway epithelium (34–37). C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonized both A549 and D562 cells, establishing burdens of ~104 CFU/mL after 4 hours and 105-6 CFU/mL by 18 hours post-inoculation (Fig. 3A), with no detectable cytotoxicity (Fig. S1A). Successful epithelial cell colonization with C. pseudodiphtheriticum enabled us to address the effect of pre-exposure on pathogen adherence, similar to the in vivo challenge model. Following an 18-hour colonization with C. pseudodiphtheriticum, D562 and A549 cells were infected with S. aureus or S. pneumoniae and adherence was calculated relative to control wells containing media without epithelial cells (Fig. 3B). Unencapsulated S. pneumoniae strain R6 was used to facilitate pneumococcal adherence to epithelial cells, which is lower in encapsulated strains (35). C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonization significantly reduced S. pneumoniae and S. aureus adherence to both D562 and A549 epithelial cells (Fig. 3C and D). The effect of C. pseudodiphtheriticum on pathogen adherence was dependent on the MOI, as S. aureus adherence was similar to non-colonized epithelial cells at lower C. pseudodiphtheriticum MOIs. However, S. aureus adherence was still significantly reduced by C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonization when the pathogen MOI was increased to 10, indicating successful interreference at a ratio as low as 1 Corynebacterium per 10 S. aureus bacterial cells (Fig. S1B). Identical conditions in wells without epithelial cells demonstrated that there was no direct pathogen killing effect under these conditions (Fig. 3E).

Fig 3.

C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonization reduces adherence of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus to human respiratory tract epithelial cells. (A) Burdens of C. pseudodiphtheriticum detected on D562 and A549 cells at 4 hours and 18 hours at the indicated MOI. LOD indicates the limit of detection. (B) Cell adherence assay schematic. (C) Percent adherence of S. pneumoniae unencapsulated strain R6 detected on D526 and A549 cells at 1 hour post-infection at MOI = 0.1 with or without pre-colonization of epithelial cells with C. pseudodiphtheriticum for 18 hours at the indicated MOI, relative to untreated cells infected with S. pneumoniae alone. (D) Percent adherence of S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 at MOI = 0.1 as for (C). (E) Burdens of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus detected in wells without epithelial cells under identical conditions as for (C and D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (A) or three independent experiments (C–E) with three replicates per condition.

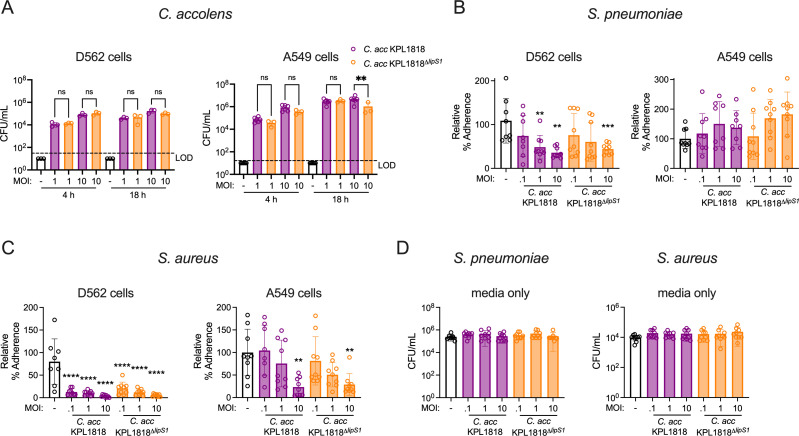

C. accolens reduces pathogen adherence to epithelial cells in a lipase-independent manner

To establish whether the colonization-associated protective effect against pathogen adherence extended to other Corynebacterium species, the same experimental set-up was used with C. accolens. First, C. accolens was confirmed to colonize D562 and A549 epithelial cells, with similar burdens established by 4 hours for both wild-type C. accolens and C. accolensΔlips1 (Fig. 4A). Burdens were also largely similar regardless of LipS1 expression at 18 hours, apart from reduced colonization for the LipS1-deficient strain at the highest MOI tested in A549 cells. C. accolens colonization significantly reduced S. pneumoniae adherence to D562 cells, and this effect was dependent on the Corynebacterium MOI (Fig. 4B), as with C. pseudodiphtheriticum. For D562 cells, on which C. accolens wild-type and LipS1-deficient strains colonized equally well, S. pneumoniae adherence was reduced following colonization with either wild-type C. accolens or C. accolensΔlips1. In contrast, C. accolens colonization was not effective against S. pneumoniae adherence to A549 cells, which was similar regardless of C. accolens or C. accolensΔlips1 pre-exposure (Fig. 4B), indicating a stronger effect against pneumococcal adherence to pharyngeal epithelial cells common to the upper airway.

Fig 4.

C. accolens colonization reduces pathogen adherence to human respiratory tract epithelial cells in a lipase-independent manner. (A) Burdens of C. accolens detected on D562 and A549 cells at 4 hours and 18 hours at the indicated MOI. LOD indicates the limit of detection. (B) Percent adherence of S. pneumoniae unencapsulated strain R6 detected on D526 and A549 cells at 1 hour post-infection at MOI = 0.1 with or without pre-colonization of epithelial cells with C. accolens WT (C. acc KPL1818) or lipS1-deficient C. accolens (C. acc KPL1818ΔlipS1) for 18 hours at the indicated MOI, relative to untreated cells infected with S. pneumoniae alone. (C) Percent adherence of S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 at MOI = 0.1 as for (B). (D) Burdens of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus detected in wells without epithelial cells under identical conditions as for (B and C). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (A) or three independent experiments (B–D) with three replicates per condition.

C. accolens interference with S. aureus adherence was more pronounced, with limited S. aureus adherence to D562 cells apparent even at the lowest C. accolens MOI tested, 0.1 (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, C. accolens also reduced S. aureus adherence to A549 cells, though this effect was only significant at the highest MOI, 10. The magnitude of Corynebacterium interference with pathogen adherence was strain-dependent, as another C. accolens isolate (ATCC strain 4926) was more effective at reducing S. aureus adherence to A549 cells, which was significantly lower at all C. accolens ATCC 4926 MOIs tested, with the greatest reduction at the highest MOI (Fig. S1C). Importantly, C. accolens-mediated impairment of S. aureus adherence was independent of LipS1 expression, as indicated by similar effects of C. accolens and C. accolensΔlips1. As with C. pseudodiphtheriticum, we observed no direct effect on pathogen growth under these conditions, based on similar S. pneumoniae and S. aureus burdens in control wells containing media without host cells (Fig. 4D). Together, these data suggest that Corynebacterium colonization of the respiratory tract epithelium is sufficient to reduce adherence of both S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, and this effect is largely independent of secreted lipase activity.

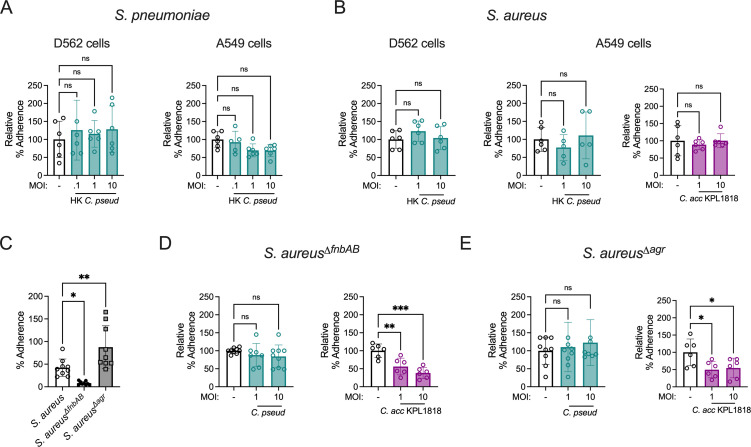

Colonization interference requires live Corynebacterium

To define the requirements for Corynebacterium inhibition of pathogen adherence, we examined the impact of HK C. pseudodiphtheriticum on adherence of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus to A549 and D562 epithelial cells. HK Corynebacterium cannot establish a resident population on the epithelial cell surface but may retain the capacity to stimulate other cellular responses. However, HK C. pseudodiphtheriticum had no effect on S. pneumoniae or S. aureus adherence (Fig. 5A and B). Similarly, HK C. accolens had no effect on S. aureus adherence to A549 cells (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that live Corynebacterium are required for reduced pathogen adherence.

Fig 5.

Corynebacterium colonization interference requires live bacteria and is sensitive to S. aureus adherence capacity. (A) Percent adherence of S. pneumoniae unencapsulated strain R6 on D562 and A549 cells 1 hour post-infection at MOI = 0.1 with or without 18 hour pre-exposure to heat-killed C. pseudodiphtheriticum (HK C. pseud) at the indicated MOI, relative to untreated cells infected with S. pneumoniae alone. (B) Percent adherence of S. aureus MRSA strain USA300 at MOI = 0.1 as for (A), with or without heat-killed C. pseudodiphtheriticum or heat-killed C. accolens WT (C. acc KPL1818). (C) Percent adherence of WT S. aureus, fnbAB-deficient S. aureus (S. aureusΔfnbAB), and agr-deficient S. aureus (S. aureusΔagr) to A549 cells 1 hour post-infection at MOI = 0.1. (D) Percent adherence of S. aureusΔfnbAB to A549 cells 1 hour post-infection at MOI = 0.1 with or without pre-colonization of epithelial cells with C. pseudodiphtheriticum or C. accolens for 18 hours at the indicated MOI, relative to untreated cells infected with S. aureusΔfnbAB alone. (E) Percent adherence of S. aureusΔagr at MOI = 0.1 as in (D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis. Data are pooled from two (A and B) or three (C–E) independent experiments with three replicates per condition.

S. aureus adherence to epithelial cells relies on a family of fibronectin-binding proteins whose expression is suppressed by the accessory gene regulator (agr) system (29, 38–40). S. aureusΔfnbAB, a fibronectin-binding protein knockout strain, was previously shown to have drastically reduced adherence to vaginal epithelial cells (41). Similarly, we found that S. aureusΔfnbAB adherence to A549 lung epithelial cells was significantly lower than that of wild-type S. aureus (Fig. 5C). In contrast, an agr-deficient strain, S. aureusΔagr, was more adherent that wild-type S. aureus. Using relative adherence to compare the effect of C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonization on the low-adherent S. aureusΔfnbAB mutant, we found that C. pseudodiphtheriticum was unable to reduce adherence any further (Fig. 5D). C. pseudodiphtheriticum colonization also had no impact on the highly adherent S. aureusΔagr mutant (Fig. 5E). Unlike C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens retained the ability to reduce both the low-adherent aureusΔfnbAB mutant and the highly adherent S. aureusΔagr mutant (Fig. 5D and E). Together, these findings suggest that C. pseudodiphtheriticum impairment of S. aureus adherence is related to competition for space or binding sites on the epithelial surface between bacteria, rather than through an indirect cell stimulatory effect, whereas C. accolens blockade of S. aureus adherence may involve additional factors.

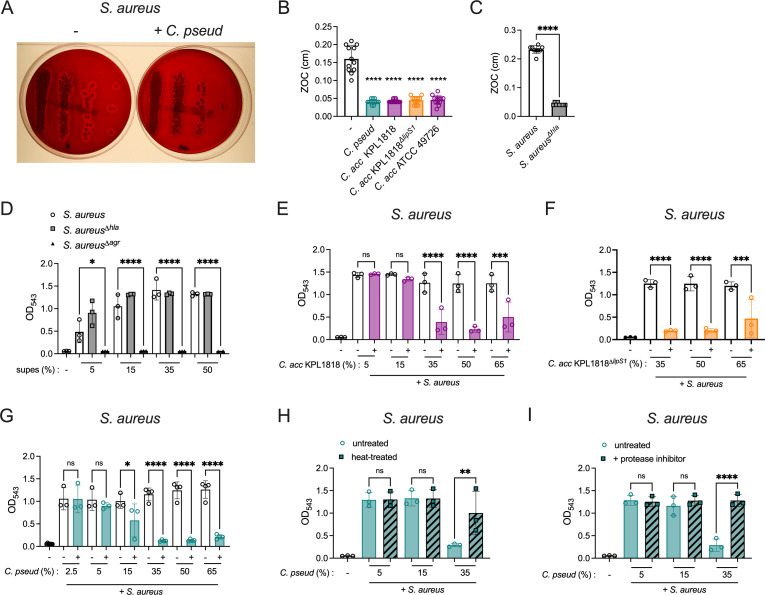

Corynebacterium-secreted factor inhibits S. aureus hemolysis

While lipases secreted by Corynebacterium had no effect on S. aureus growth, we considered the potential effect of lipases or other secreted factors on S. aureus virulence. The agr quorum sensing system impacts the regulation of many key virulence factors in S. aureus (42, 43). Among these are the pore-forming toxins (PFTs), which lyse diverse host cell types including erythrocytes (44). CFCM from several Corynebacterium species were tested for an impact on S. aureus hemolysis using two different in vitro assays. First, Corynebacterium CFCM was spread onto 5% sheep blood agar plates before plating S. aureus. Hemolysis is visualized by the “aura” of lysed erythrocytes, quantified by ZOC. We found that several strains of Corynebacterium CFCM drastically reduced the hemolytic activity of S. aureus, visualized by a reduced transparent aura of lysed erythrocytes on the plates (Fig. 6A; Fig. S2A), and by the measured ZOC (Fig. 6B). This effect was lipase-independent, as both C. accolens and C. accolensΔlips1 significantly reduced hemolytic activity. Sheep blood agar hemolysis was dependent on the PFT α-hemolysin (Hla), as hemolysis was absent in a S. aureusΔhla mutant (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that Corynebacterium-secreted factors inhibit α-hemolysin-dependent hemolysis. In contrast, we detected no effect for Corynebacterium CFCM on the characteristic “green halo” produced by S. pneumoniae in 5% sheep blood agar plates (Fig. S2B), indicating a selective effect on S. aureus hemolysis.

Fig 6.

Corynebacterium-secreted factor directly inhibits S. aureus hemolysin activity. (A) S. aureus colonies on sheep blood agar plates with or without pre-spreading plates with filtered supernatants (CFCM) from C. pseudodiphtheriticum (C. pseud), with hemolysis visualized as cleared zones surrounding colonies. (B) ZOC quantified for S. aureus colonies on sheep blood agar plates with or without pre-spreading of CFCM from C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens WT (C. acc KPL1818), lipS1-deficient C. accolens (C. acc KPL1818ΔlipS1), or C. accolens ATCC 49726. (C) ZOC quantified for WT S. aureus compared with hla-deficient S. aureus (S. aureusΔhla) on blood agar plates. (D) Hemolysis detected as OD543 of human red blood cells combined with the indicated percentage of filtered S. aureus supernatants from WT S. aureus, S. aureusΔhla, and S. aureusΔagr. (E and F) Hemolysis of human red blood cells combined with filtered S. aureus supernatant and the indicated percentage of filtered supernatants (CFCM) from C. accolens WT (C. acc KPL1818) (E), or lipS1-deficient C. accolens (C. acc KPL1818ΔlipS1) (F) or an equivalent percentage of growth medium alone. (G) Hemolysis of human red blood cells combined with filtered S. aureus supernatant and the indicated percentage of CFCM from C. pseudodiphtheriticum or an equivalent percentage of growth medium alone. (H) Hemolysis of human red blood cells as in (G) for S. aureus supernatants combined with untreated or heat-treated CFCM from C. pseudodiphtheriticum. (I) Hemolysis of human red blood cells as in (G) for S. aureus supernatants combined with CFCM from C. pseudodiphtheriticum with or without a protease inhibitor cocktail. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc analysis (B), Tukey’s post hoc analysis (D), or Sidak’s post hoc analysis (E–I), or unpaired t-test (C). Data are representative of three experiments (A), pooled from three independent experiments with three replicates per group (B) or pooled from three to four independent experiments with one replicate per group (E–I).

We next investigated S. aureus hemolysis of human blood using a spectroscopy assay. For this assay, S. aureus cultures were used to prepare S. aureus CFCM, which contains several PFTs, and hemolysis was measured following incubation with human red blood cells. Higher values of OD543 indicate greater levels of hemolysis, as reaction mixtures were centrifuged to pellet intact red blood cells. Importantly, human erythrocytes lack the receptor for α-hemolysin, ADAM10, rendering them insensitive to α-hemolysin-dependent hemolysis (45, 46). Consistent with this, CFCM from wild-type S. aureus and S. aureusΔhla resulted in similar levels of hemolysis (Fig. 6D). Human erythrocytes are sensitive to other S. aureus PFTs including leukocidins and phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) (47, 48). Agr is critical for expression of both α-hemolysin and other PFTs capable of lysing human red blood cells (42, 47). In contrast to CFCM from wild-type S. aureus, CFCM from agr-deficient S. aureus exhibited no hemolytic activity (Fig. 6D), as expected. Thus, hemolytic activity measured in this assay with human red blood cells represents α-hemolysin-independent hemolysis. To assess the effect of Corynebacterium CFCM on S. aureus hemolysis of human red blood cells, Corynebacterium CFCM was combined with S. aureus CFCM and purified human erythrocytes. Both C. pseudodiphtheriticum and C. accolens CFCM significantly reduced S. aureus hemolysis, compared to control reactions without Corynebacterium CFCM (Fig. 6E through G; Fig. S2C). C. accolens CFCM inhibition did not require lipase activity, as S. aureus hemolysis was blocked by CFCM from both C. accolens and C. accolensΔlips1 (Fig. 6E and F). Corynebacterium CFCM inhibition of S. aureus hemolysis was dose-dependent, with optimal inhibition above 15% CFCM (Fig. 6E and G). These data indicate that a secreted factor from Corynebacterium directly inhibits the activity of S. aureus hemolytic toxins.

To characterize the secreted factor(s) responsible, we compared activity of C. pseudodiphtheriticum CFCM after heat treatment and following incubation with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The inhibitor cocktail consisted of AEBSF, Aprotinin, Bestatin, E64, Leupeptin, and Pepstatin A inhibitors, providing broad-spectrum inhibition of activity by serine proteases, cysteine proteases, aspartic acid proteases, aminopeptidases, and metalloproteases. Heat-treated Corynebacterium CFCM displayed a significantly reduced effect, as S. aureus CFCM hemolysis was largely restored (Fig. 6H), suggesting that the secreted factor is heat-labile. Incubation of C. pseudodiphtheriticum CFCM with a protease inhibitor cocktail also restored S. aureus hemolysis activity (Fig. 6I). Control reactions with DMSO alone had no effect on S. aureus hemolysis (Fig. S2D). Finally, C. pseudodiphtheriticum CFCM activity was lost after passage through a 10 kD molecular weight filter, but retained in the >10 kD fraction, suggesting that the hemolysis inhibitory factor is not a small molecule or metabolite (Fig. S2E). Together, these findings identify a Corynebacterium-secreted factor whose protease activity directly inhibits S. aureus hemolysis.

DISCUSSION

The airway epithelium is a battleground for the millions of bacteria colonizing our respiratory tract, primarily residing in the upper airway. Classified by the World Health Organization as “priority pathogens,” S. aureus and S. pneumoniae frequently colonize the upper airway and cause bacterial pneumonia upon invasion to the lungs. In contrast, Corynebacterium function largely as commensal bacteria in the airway and correlate with reduced respiratory tract infection risk (17–20). This study expands our understanding of the mechanisms by which Corynebacterium impact Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenesis by defining species-conserved and species-specific effects against pathogen infection, adherence to the airway epithelium, growth, and virulence.

Adherence to the respiratory tract epithelium is a key pre-requisite for colonization, infection, and future disease spread for both S. pneumoniae and S. aureus. The polysaccharide capsule of S. pneumoniae plays an important role in defense against host immune responses (49). However, during colonization, S. pneumoniae sheds its capsular polysaccharide to promote epithelial adherence through increased exposure of cell adhesion molecules (50), motivating our use of unencapsulated R6 to assess pneumococcal adherence to respiratory tract epithelial cells. S. aureus adherence is largely regulated by microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) (51). The fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs FnbA and FnbB are critical for colonization and invasion of host tissue (39, 52, 53). Here, we found that Corynebacterium successfully colonize D562 and A549 respiratory tract epithelial cells, providing a new investigative tool to dissect Corynebacterium interactions with host cells and other bacteria. These studies identify two Corynebacterium species, C. pseudodiphtheriticum and C. accolens, which broadly inhibit adherence of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus to human respiratory tract epithelial cells. Additional studies will be necessary to determine whether other S. pneumoniae and S. aureus isolates are similarly affected. The mechanism for C. pseudodiphtheriticum interference with pathogen adhesion is likely related to direct competition from the colonizing Corynebacterium, suggested by the dose dependence of this effect, requirement for live Corynebacterium, and limited effect on S. aureus mutants with significantly low or high baseline adherence. This aligns well with the current model for pathogen interference from resident microbial populations colonizing the mucosal surface, which limit the available “real estate” on the epithelium for pathogens to establish a niche. While C. accolens inhibition of S. aureus adherence also required live bacteria, this strain was still effective against highly adherent and low adherent S. aureus, indicating strain-dependent differences for this phenotype and the potential involvement of factors beyond epithelial colonization, as both strains colonized similarly well. Beyond direct niche competition, secreted proteases from Corynebacterium, such as those responsible for directly impairing S. aureus hemolysis, may alter adherence factors including FnbA and FnbB or interfere with their binding. The effect of Corynebacterium protease activity on S. aureus and S. pneumoniae adherence and the mechanisms underlying strain-dependent differences remain important areas for further investigation.

In mice, we found that pre-exposure to C. pseudodiphtheriticum reduced colonization and lung infection with both S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, though the effect was more pronounced against S. pneumoniae. In prior work, we established that C. accolens similarly reduced S. pneumoniae infection, and this effect was partially dependent on LipS1 (23). Secreted lipases including C. accolens LipS1 directly inhibit pneumococcal growth through the release of bactericidal free fatty acids following host lipid catabolism (32). C. accolens is lipophilic, as it requires free fatty acids to grow (54). However, several non-lipophilic Corynebacterium species including C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. striatum, and C. amycolatum demonstrated lipase activity, as S. pneumoniae growth was only inhibited in the presence of the host lipid triolein. Among these, we previously identified a lipase in C. amycolatum responsible for triolein-dependent inhibition of S. pneumoniae (23). In C. pseudodiphtheriticum, the protein with highest homology to LipS1 is WP_244266826.1, categorized as an alpha/beta hydrolase family protein, like LipS1, in the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (55). This protein, potentially together with other lipases expressed by C. pseudodiphtheriticum, may contribute to triolein hydrolysis in this strain. In addition to triolein digestion by LipS1, bacterial lipases and esterases can hydrolyze Tween 80, used in the growth medium, serving as an additional source of free fatty acid release as we observed for the Corynebacterium strains that inhibited S. pneumoniae without triolein. Regardless, lipase expression did not contribute to reduced pneumococcal adherence to respiratory tract epithelial cells colonized with C. accolens. The concentration of Corynebacterium-secreted lipase, along with the proximity or availability of host-derived lipid, was likely insufficient to mediate direct growth inhibition in this setting. Future work in air liquid interface (ALI) cultures, where cells are not submerged in culture media, may better facilitate investigation of lipase-dependent effects. The use of more complex epithelial models, such as primary human epithelial ALI cultures comprised of ciliated and mucous secreting cells, is an important next step in translating the findings presented here to understand Corynebacterium dynamics with bacterial pathogens occurring at the airway epithelium. Regardless, these findings suggest that both lipase-dependent and -independent mechanisms contribute to Corynebacterium-mediated protection against pneumococcal colonization and infection.

The agr quorum sensing system in S. aureus regulates secretion of a large suite of virulence factors and adhesion molecules. In response to higher cell population density and increased levels of autoinducing peptide (AIP), agr activation leads to increased expression of virulence factors while adhesion is downregulated (40, 56–58). This process reflects the stages of S. aureus infection; upon initial tissue colonization, adhesion factors are upregulated, but as pathogen cell density increases, the population requires more nutritional resources and immune evasion mechanisms become critical (59–61). Agr is required for S. aureus invasion of the lungs and increases S. aureus-associated mortality (62, 63). Agr has also been implicated in Corynebacterium-Staphylococcus interactions, as S. aureus with spontaneous agr mutations survive contact-dependent growth inhibition by C. pseudodiphtheriticum on agar plates (64). Prior work by Ramsey et al. found that CFCM from Corynebacterium striatum reduced S. aureus agr activation (65). In their study, S. aureus incubated with C. striatum CFCM in the presence of AIP was more adherent to A549 epithelial cells. These data align with our finding that S. aureus adherence is increased in the absence of agr. Increased adherence in agr-deficient S. aureus may result from relief of fibronectin-binding protein inhibition and reduced production of protease V8, which cleaves fibronectin-binding proteins (66). However, live colonizing Corynebacterium had the opposite effect, and instead reduced S. aureus adherence to epithelial cells. These findings suggest that Corynebacterium can interfere with initial S. aureus attachment to the respiratory epithelium. However, once S. aureus is established and AIP-induced agr is triggered, Corynebacterium-secreted factor(s) reported in Ramsey et al. may reduce virulence. It remains unclear whether these mechanisms occur simultaneously or compete with one another during S. aureus colonization and infection in vivo.

S. aureus PFTs, which are regulated by the agr system, can lyse an array of human cell types, including monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, epithelial cells, and erythrocytes (44, 67). The major S. aureus PFT categories are hemolysins (α-, β-, and γ-), leukocidins, and PSMs. These toxins are critical for virulence, playing an important role during S. aureus pneumonia (63), skin infection (68), and sepsis (69). In the previously mentioned study by Ramsey et al., S. aureus hemolysis was reduced following growth in C. striatum CFCM, which downregulated S. aureus agr activity and virulence gene expression in the presence of AIP. Unexpectedly, we found that CFCM from multiple Corynebacterium strains directly interfered with the activity of S. aureus hemolysins, as Corynebacterium CFCM was added to S. aureus CFCM, rather than live cells, without the opportunity to affect gene expression. In this setting, Corynebacterium CFCM was sufficient to block both α-hemolysin-dependent and -independent hemolysis, indicating interference with multiple PFTs. This anti-hemolytic activity was abolished in the presence of a protease inhibitor, suggesting that a Corynebacterium-secreted protease is responsible. In contrast to this unidentified protease, which we found was larger than ~10 kD, the secreted factor described by Ramsey et al. to alter S. aureus gene regulation was a small molecule under 3 kD. Together, these findings indicate that distinct Corynebacterium-secreted factors modulate S. aureus virulence gene expression and directly interfere with PFT activity. S. pneumoniae growth on blood agar plates produces a “green halo” often described as α-hemolysis, due to hydrogen peroxide oxidation of oxy-hemoglobin (70). Corynebacterium-secreted factors had no impact on S. pneumoniae hemoglobin oxidation, which occurs through alternative mechanisms to S. aureus PFTs.

The commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis also secretes a factor in CFCM that impairs S. aureus hemolysis, though this effect was mediated by regulation of S. aureus gene expression (71), as reported for C. striatum. S. aureus produces several proteases including aureolysin, a metalloproteinase that modulates hypervirulence in S. aureus infection by preventing accumulation of α-hemolysin and phenol-soluble modulins (72–74). While we were unable to identify aureolysin homologs in the Corynebacterium strains used in this study, the Corynebacterium-derived protease(s) we describe may interfere with S. aureus hemolysis through a similar mechanism. The Corynebacterium strains investigated in this study encode genes for several classes of proteases including metalloproteases, serine proteases, and cysteine proteases. These include proteases with homologs in the exoproteome of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, indicating they are likely secreted (75). Corynebacterium proteases could also influence other S. aureus phenotypes including adherence, as mentioned above, if fibronectin-binding proteins are targeted similar to S. aureus-derived V8 protease (66). It was recently shown that PSMs secreted by S. aureus can interfere with C. pseudodiphtheriticum aggregation and colonization of nasal epithelial cells (76), suggesting bi-directional interactions between Corynebacterium and S. aureus PFTs.

Overall, these findings support the notion that commensal Corynebacterium species in the upper airway contribute to the beneficial effect of the respiratory tract microbiome by identifying new mechanisms by which Corynebacterium species protect against colonization and lung infection by opportunistic pathogens. These protective mechanisms include interference with pathogen adherence to the respiratory tract epithelium as well as the secretion of factors that impede pneumococcal growth and S. aureus virulence. Identifying the conditions under which Corynebacterium impairs pathogen colonization and the secreted factors regulating their growth and virulence is a critical next step toward developing Corynebacterium-based therapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were funded by a Boettcher Foundation Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Award (S.E.C.) and a sponsored research agreement with Trench Therapeutics, Inc. (S.E.C.).

E.T. was responsible for investigation, methodology, data curation, conceptualization, and writing. B.P.L. was responsible for investigation, methodology, data curation, conceptualization, and writing. A.M. and S.F. were responsible for investigation, methodology, and data curation. E.E. was responsible for methodology. A.R.H. was responsible for conceptualization and methodology. S.E.C. was responsible for funding acquisition, conceptualization, formal analysis, project administration, supervision, and writing.

AFTER EPUB

[This article was published on 20 December 2024 with an error in the abstract. The first line of the abstract was corrected in the current version, posted on 8 January 2025.]

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Clark, Email: sarah.e.clark@cuanschutz.edu.

Marvin Whiteley, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #00927). All work with bacteria was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (protocol #1418) of the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Blood draws from healthy adults were approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (protocol #05–-0993).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00445-24.

Fig. S1 and S2.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weiser JN, Ferreira DM, Paton JC. 2018. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:355–367. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . 2022. Pneumonia in children. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pneumonia

- 3. Brooks LRK, Mias GI. 2018. Streptococcus pneumoniae’s virulence and host immunity: aging, diagnostics, and prevention. Front Immunol 9:1366. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bogaert D, De Groot R, Hermans PWM. 2004. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis 4:144–154. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wertheim HFL, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. 2005. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis 5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morris DE, Cleary DW, Clarke SC. 2017. Secondary bacterial infections associated with influenza pandemics. Front Microbiol 8:1041. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith AM, McCullers JA. 2014. Secondary bacterial infections in influenza virus infection pathogenesis, p 327–356. In Compans RW, Oldstone MBA (ed), Influenza pathogenesis and control. Springer International Publishing, Cham. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S) . 2019. In Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turner NA, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Maskarinec SA, Eichenberger EM, Shah PP, Carugati M, Holland TL, Fowler VG. 2019. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:203–218. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0147-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clegg J, Soldaini E, McLoughlin RM, Rittenhouse S, Bagnoli F, Phogat S. 2021. Staphylococcus aureus vaccine research and development: the past, present and future, including novel therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol 12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.705360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drigot ZG, Clark SE. 2024. Insights into the role of the respiratory tract microbiome in defense against bacterial pneumonia. Curr Opin Microbiol 77:102428. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2024.102428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Man WH, van Houten MA, Mérelle ME, Vlieger AM, Chu MLJN, Jansen NJG, Sanders EAM, Bogaert D. 2019. Bacterial and viral respiratory tract microbiota and host characteristics in children with lower respiratory tract infections: a matched case-control study. Lancet Respir Med 7:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30449-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lappan R, Imbrogno K, Sikazwe C, Anderson D, Mok D, Coates H, Vijayasekaran S, Bumbak P, Blyth CC, Jamieson SE, Peacock CS. 2018. A microbiome case-control study of recurrent acute otitis media identified potentially protective bacterial genera. BMC Microbiol 18:13. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1154-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pettigrew MM, Laufer AS, Gent JF, Kong Y, Fennie KP, Metlay JP. 2012. Upper respiratory tract microbial communities, acute otitis media pathogens, and antibiotic use in healthy and sick children. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6262–6270. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01051-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yan M, Pamp SJ, Fukuyama J, Hwang PH, Cho D-Y, Holmes S, Relman DA. 2013. Nasal microenvironments and interspecific interactions influence nasal microbiota complexity and S. aureus carriage. Cell Host Microbe 14:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu L, Earl J, Pichichero ME. 2021. Nasopharyngeal microbiome composition associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization suggests a protective role of corynebacterium in young children. PLoS ONE 16:e0257207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly MS, Plunkett C, Yu Y, Aquino JN, Patel SM, Hurst JH, Young RR, Smieja M, Steenhoff AP, Arscott-Mills T, Feemster KA, Boiditswe S, Leburu T, Mazhani T, Patel MZ, Rawls JF, Jawahar J, Shah SS, Polage CR, Cunningham CK, Seed PC. 2022. Non-diphtheriae corynebacterium species are associated with decreased risk of pneumococcal colonization during infancy. ISME J 16:655–665. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-01108-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bosch A, de Steenhuijsen Piters WAA, van Houten MA, Chu M, Biesbroek G, Kool J, Pernet P, de Groot P-K, Eijkemans MJC, Keijser BJF, Sanders EAM, Bogaert D. 2017. Maturation of the infant respiratory microbiota, environmental drivers, and health consequences. a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196:1582–1590. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0554OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teo SM, Mok D, Pham K, Kusel M, Serralha M, Troy N, Holt BJ, Hales BJ, Walker ML, Hollams E, Bochkov YA, Grindle K, Johnston SL, Gern JE, Sly PD, Holt PG, Holt KE, Inouye M. 2015. The infant nasopharyngeal microbiome impacts severity of lower respiratory infection and risk of asthma development. Cell Host Microbe 17:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Biesbroek G, Tsivtsivadze E, Sanders EAM, Montijn R, Veenhoven RH, Keijser BJF, Bogaert D. 2014. Early respiratory microbiota composition determines bacterial succession patterns and respiratory health in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190:1283–1292. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1240OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Uehara Y, Nakama H, Agematsu K, Uchida M, Kawakami Y, Abdul Fattah ASM, Maruchi N. 2000. Bacterial interference among nasal inhabitants: eradication of Staphylococcus aureus from nasal cavities by artificial implantation of Corynebacterium sp. J Hosp Infect 44:127–133. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanmani P, Clua P, Vizoso-Pinto MG, Rodriguez C, Alvarez S, Melnikov V, Takahashi H, Kitazawa H, Villena J. 2017. Respiratory commensal bacteria Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum improves resistance of infant mice to respiratory syncytial virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae superinfection. Front Microbiol 8:1613. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horn KJ, Jaberi Vivar AC, Arenas V, Andani S, Janoff EN, Clark SE. 2022. Corynebacterium species inhibit Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization and infection of the mouse airway. Front Microbiol 12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.804935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Menberu MA, Liu S, Cooksley C, Hayes AJ, Psaltis AJ, Wormald P-J, Vreugde S. 2021. Corynebacterium accolens has antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus pathogens isolated from the sinonasal niche of chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Pathogens 10:207. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Menberu MA, Cooksley C, Ramezanpour M, Bouras G, Wormald P-J, Psaltis AJ, Vreugde S. 2021. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of probiotic properties of Corynebacterium accolens isolated from the human nasal cavity. Microbiol Res 255:126927. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wen Z, Sertil O, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Liu X, Wang W-C, Zhang J-R. 2015. Sequence elements upstream of the core promoter are necessary for full transcription of the capsule gene operon in Streptococcus pneumoniae strain D39. Infect Immun 83:1957–1972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02944-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lanie JA, Ng W-L, Kazmierczak KM, Andrzejewski TM, Davidsen TM, Wayne KJ, Tettelin H, Glass JI, Winkler ME. 2007. Genome sequence of Avery’s virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J Bacteriol 189:38–51. doi: 10.1128/JB.01148-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kennedy AD, Otto M, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Chen L, Mathema B, Mediavilla JR, Byrne KA, Parkins LD, Tenover FC, Kreiswirth BN, Musser JM, DeLeo FR. 2008. Epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: recent clonal expansion and diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:1327–1332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710217105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deng L, Schilcher K, Burcham LR, Kwiecinski JM, Johnson PM, Head SR, Heinrichs DE, Horswill AR, Doran KS. 2019. Identification of key determinants of Staphylococcus aureus vaginal colonization. MBio 10:e02321-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02321-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kiedrowski MR, Kavanaugh JS, Malone CL, Mootz JM, Voyich JM, Smeltzer MS, Bayles KW, Horswill AR. 2011. Nuclease modulates biofilm formation in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 6:e26714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Olson ME, Nygaard TK, Ackermann L, Watkins RL, Zurek OW, Pallister KB, Griffith S, Kiedrowski MR, Flack CE, Kavanaugh JS, Kreiswirth BN, Horswill AR, Voyich JM. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus nuclease is an SaeRS-dependent virulence factor. Infect Immun 81:1316–1324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01242-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bomar L, Brugger SD, Yost BH, Davies SS, Lemon KP. 2016. Corynebacterium accolens releases antipneumococcal free fatty acids from human nostril and skin surface triacylglycerols. MBio 7:e01725-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01725-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ortiz Moyano R, Dentice Maidana S, Imamura Y, Elean M, Namai F, Suda Y, Nishiyama K, Melnikov V, Kitazawa H, Villena J. 2024. Antagonistic effects of Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum 090104 on respiratory pathogens. Microorganisms 12:1295. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12071295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khan MN, Pichichero ME. 2012. Vaccine candidates PhtD and PhtE of Streptococcus pneumoniae are adhesins that elicit functional antibodies in humans. Vaccine (Auckl) 30:2900–2907. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Novick S, Shagan M, Blau K, Lifshitz S, Givon-Lavi N, Grossman N, Bodner L, Dagan R, Mizrachi Nebenzahl Y. 2017. Adhesion and invasion of Streptococcus pneumoniae to primary and secondary respiratory epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep 15:65–74. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang Y-H, Jiang Y-L, Zhang J, Wang L, Bai X-H, Zhang S-J, Ren Y-M, Li N, Zhang Y-H, Zhang Z, Gong Q, Mei Y, Xue T, Zhang J-R, Chen Y, Zhou C-Z. 2014. Structural insights into SraP-mediated Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to host cells. PLOS Pathog 10:e1004169. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Van Wamel WJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. 1998. The effect of culture conditions on the in-vitro adherence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol 47:705–709. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-8-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mongodin E, Bajolet O, Cutrona J, Bonnet N, Dupuit F, Puchelle E, de Bentzmann S. 2002. Fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus are involved in adherence to human airway epithelium. Infect Immun 70:620–630. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.620-630.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Höök M. 2014. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vergara-Irigaray M, Valle J, Merino N, Latasa C, García B, Ruiz de Los Mozos I, Solano C, Toledo-Arana A, Penadés JR, Lasa I. 2009. Relevant role of fibronectin-binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm-associated foreign-body infections. Infect Immun 77:3978–3991. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00616-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lyon LM, Doran KS, Horswill AR. 2023. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding proteins contribute to colonization of the female reproductive tract. Infect Immun 91:e0046022. doi: 10.1128/iai.00460-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamazaki Y, Ito T, Tamai M, Nakagawa S, Nakamura Y. 2024. The role of Staphylococcus aureus quorum sensing in cutaneous and systemic infections. Inflamm Regen 44:9. doi: 10.1186/s41232-024-00323-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jenul C, Horswill AR. 2019. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Microbiol Spectr 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tam K, Torres VJ. 2019. Staphylococcus aureus secreted toxins and extracellular enzymes. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0039-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Inoshima I, Inoshima N, Wilke GA, Powers ME, Frank KM, Wang Y, Bubeck Wardenburg J. 2011. A Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxin subverts the activity of ADAM10 to cause lethal infection in mice. Nat Med 17:1310–1314. doi: 10.1038/nm.2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilke GA, Bubeck Wardenburg J. 2010. Role of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 in Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13473–13478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001815107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vasquez MT, Lubkin A, Reyes-Robles T, Day CJ, Lacey KA, Jennings MP, Torres VJ. 2020. Identification of a domain critical for Staphylococcus aureus LukED receptor targeting and lysis of erythrocytes. J Biol Chem 295:17241–17250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cheung GYC, Duong AC, Otto M. 2012. Direct and synergistic hemolysis caused by Staphylococcus phenol-soluble modulins: implications for diagnosis and pathogenesis. Microbes Infect 14:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paton JC, Trappetti C. 2019. Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0019-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hammerschmidt S, Wolff S, Hocke A, Rosseau S, Müller E, Rohde M. 2005. Illustration of pneumococcal polysaccharide capsule during adherence and invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun 73:4653–4667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4653-4667.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Foster TJ. 2019. Surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0046-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sinha B, Francois P, Que YA, Hussain M, Heilmann C, Moreillon P, Lew D, Krause KH, Peters G, Herrmann M. 2000. Heterologously expressed Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding proteins are sufficient for invasion of host cells. Infect Immun 68:6871–6878. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6871-6878.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peacock SJ, Foster TJ, Cameron BJ, Berendt AR. 1999. Bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins and endothelial cell surface fibronectin mediate adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to resting human endothelial cells. Microbiol (Reading) 145 ( Pt 12):3477–3486. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-12-3477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bernard K. 2012. The genus Corynebacterium and other medically relevant Coryneform-like bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:3152–3158. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00796-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lu S, Wang J, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yang M, Zhang D, Zheng C, Lanczycki CJ, Marchler-Bauer A. 2020. CDD/SPARCLE: the conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48:D265–D268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cheung GYC, Wang R, Khan BA, Sturdevant DE, Otto M. 2011. Role of the accessory gene regulator agr in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Infect Immun 79:1927–1935. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00046-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dunman PM, Murphy E, Haney S, Palacios D, Tucker-Kellogg G, Wu S, Brown EL, Zagursky RJ, Shlaes D, Projan SJ. 2001. Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J Bacteriol 183:7341–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7341-7353.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Novick RP, Geisinger E. 2008. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu Rev Genet 42:541–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chaves-Moreno D, Wos-Oxley ML, Jáuregui R, Medina E, Oxley AP, Pieper DH. 2016. Exploring the transcriptome of Staphylococcus aureus in its natural niche. Sci Rep 6:33174. doi: 10.1038/srep33174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bastakoti S, Ajayi C, Julin K, Johannessen M, Hanssen A-M. 2023. Exploring differentially expressed genes of Staphylococcus aureus exposed to human tonsillar cells using RNA sequencing. BMC Microbiol 23:185. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-02919-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Le KY, Otto M. 2015. Quorum-sensing regulation in staphylococci-an overview. Front Microbiol 6:1174. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Heyer G, Saba S, Adamo R, Rush W, Soong G, Cheung A, Prince A. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus agr and sarA functions are required for invasive infection but not inflammatory responses in the lung. Infect Immun 70:127–133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.127-133.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Patel RJ, Schneewind O. 2007. Surface proteins and exotoxins are required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect Immun 75:1040–1044. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hardy BL, Dickey SW, Plaut RD, Riggins DP, Stibitz S, Otto M, Merrell DS. 2019. Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum exploits Staphylococcus aureus virulence components in a novel polymicrobial defense strategy. MBio 10:e02491-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02491-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ramsey MM, Freire MO, Gabrilska RA, Rumbaugh KP, Lemon KP. 2016. Staphylococcus aureus shifts toward commensalism in response to corynebacterium species. Front Microbiol 7:1230. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McGavin MJ, Zahradka C, Rice K, Scott JE. 1997. Modification of the Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin binding phenotype by V8 protease. Infect Immun 65:2621–2628. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2621-2628.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dong J, Qiu J, Zhang Y, Lu C, Dai X, Wang J, Li H, Wang X, Tan W, Luo M, Niu X, Deng X. 2013. Oroxylin a inhibits hemolysis via hindering the self-assembly of α-hemolysin heptameric transmembrane pore. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e1002869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kennedy AD, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Gardner DJ, Long D, Whitney AR, Braughton KR, Schneewind O, DeLeo FR. 2010. Targeting of alpha-hemolysin by active or passive immunization decreases severity of USA300 skin infection in a mouse model. J Infect Dis 202:1050–1058. doi: 10.1086/656043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Surewaard BGJ, Thanabalasuriar A, Zeng Z, Tkaczyk C, Cohen TS, Bardoel BW, Jorch SK, Deppermann C, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Davis RP, Jenne CN, Stover KC, Sellman BR, Kubes P. 2018. Alpha toxin induces platelet aggregation and liver injury during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 24:271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McDevitt E, Khan F, Scasny A, Thompson CD, Eichenbaum Z, McDaniel LS, Vidal JE. 2020. Hydrogen peroxide production by Streptococcus pneumoniae results in alpha-hemolysis by oxidation of oxy-hemoglobin to met-hemoglobin. mSphere 5:e01117-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.01117-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nurxat N, Wang L, Wang Q, Li S, Jin C, Shi Y, Wulamu A, Zhao N, Wang Y, Wang H, Li M, Liu Q. 2023. Commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis defends against Staphylococcus aureus through SaeRS Two-component system. ACS Omega 8:17712–17718. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c00263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gimza BD, Jackson JK, Frey AM, Budny BG, Chaput D, Rizzo DN, Shaw LN. 2021. Unraveling the impact of secreted proteases on hypervirulence in Staphylococcus aureus. MBio 12:e03288-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03288-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zielinska AK, Beenken KE, Joo H-S, Mrak LN, Griffin LM, Luong TT, Lee CY, Otto M, Shaw LN, Smeltzer MS. 2011. Defining the strain-dependent impact of the Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sarA) on the alpha-toxin phenotype of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 193:2948–2958. doi: 10.1128/JB.01517-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kolar SL, Ibarra JA, Rivera FE, Mootz JM, Davenport JE, Stevens SM, Horswill AR, Shaw LN. 2013. Extracellular proteases are key mediators of Staphylococcus aureus virulence via the global modulation of virulence-determinant stability. Microbiologyopen 2:18–34. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Goring AK, Hale ST, Dasika P, Chen Y, Clubb RT, Loo JA. 2024. The exoproteome and surfaceome of toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae 1737 and its response to iron-restriction and growth on human hemoglobin. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2024.05.19.594877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Huffines JT, Kiedrowski MR. 2024. Staphylococcus aureus phenol-soluble modulins mediate interspecies competition with upper respiratory commensal bacteria. bioRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2024.09.24.614779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 and S2.