Abstract

The insect GST (glutathione transferase) supergene family encodes a varied group of proteins belonging to at least six individual classes. Interest in insect GSTs has focused on their role in conferring insecticide resistance. Previously from the mosquito malaria vector Anopheles dirus, two genes encoding five Delta class GSTs have been characterized for structural as well as enzyme activities. We have obtained a new Delta class GST gene and isoenzyme from A. dirus, which we name adGSTD5-5. The adGSTD5-5 isoenzyme was identified and was only detectably expressed in A. dirus adult females. A putative promoter analysis suggests that this GST has an involvement in oogenesis. The enzyme displayed little activity for classical GST substrates, although it possessed the greatest activity for DDT [1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(p-chlorophenyl)ethane] observed for Delta GSTs. However, GST activity was inhibited or enhanced in the presence of various fatty acids, suggesting that the enzyme may be modulated by fatty acids. We obtained a crystal structure for adGSTD5-5 and compared it with other Delta GSTs, which showed that adGSTD5-5 possesses an elongated and more polar active-site topology.

Keywords: Anopheles dirus, crystal structure, Delta class glutathione transferase, enzyme characterization, glutathione transferase gene, regulatory element

Abbreviations: AP-1, activator protein 1; CDNB, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene; DDT, 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(p-chlorophenyl)ethane; GST, glutathione transferase; RMSD, root mean square deviation

INTRODUCTION

The insect GST (glutathione transferase) (EC 2.5.1.18) supergene family encodes a diverse set of proteins belonging to at least six individual classes (Delta, Epsilon, Sigma, Theta, Zeta, Omega and several unclassified genes) [1]. Interest in insect GSTs has focused on their role in conferring insecticide resistance [2] and in protecting against cellular damage by oxidative stress [3]. Many resistant insects are associated with elevated levels of GST activity [4]. In Anopheles dirus, two genes encoding five GST isoenzymes from the Delta class have been acquired previously and characterized for structural as well as enzyme activities [5–8]. To this end, we have identified a new Delta class GST isoenzyme from Anopheles dirus species B, which we named adGSTD5-5 (in insect GST nomenclature, ‘D’ refers to the Delta class and ‘5-5’ refers to the homodimeric isoenzyme [9,10]). The availability of the A. dirus genome sequence has also enabled a putative promoter prediction, which suggests that this GST is involved in developmental-stage regulation. Moreover, the adGSTD5-5 enzyme was expressed and studied for structural as well as functional characteristics. The crystal structure of adGSTD5-5 was also obtained. Our data therefore reveal an overview of an evolutionarily conserved enzyme from gene to protein function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic isolation of gstD5

A. dirus genomic library construction and screening was performed as described previously [7]. Using lower stringency hybridization, the presence of another GST gene was revealed on the phage clone of adgst1AS1. The recombinant phage clone 8A.2 was sequenced further until the complete sequence of 15694 bp for the insert was obtained (GenBank® accession number AF251478).

adGSTD5-5 expression construct

The mRNAs were isolated from the fourth instar larvae, pupae, male and female adults by using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL) and the oligo(dT)15 primer 5′-GGCGGTCGACATATG(dT)15-3′ (Proligo Singapore Pty), as described in the instruction manual. The N-terminus primer (5′-CACGCCGCATATGACGACGGTGCTGTACTATC-3′) and C-terminus primer (5′-CGCCGTCGACATATGCTACTGCTTCAACTTCGA-3′) were designed from the N-terminus and C-terminus of the amino acid coding region. The initial codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAG) are underlined, and the NdeI recognition site also incorporated in both primers is shown in bold. The PCR amplification (35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and then a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min) was performed on a PE system 2400 (PerkinElmer). The PCR product was purified from gel by GENECLEAN® II kit (BIO 101, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) following the manufacturer's instructions. The purified PCR product was digested with NdeI, and ligated into pET3a (Novagen) at the NdeI site. The ligated reaction was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α cells. Then the recombinant clones were sequenced in both directions. Finally, the recombinant clones were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS competent cells for protein expression. The expression and purification of the recombinant enzyme was performed as described previously [11].

Characterization of the recombinant adGSTD5-5 enzyme

GST assay

Steady-state kinetics were studied for adGSTD5-5 at varying concentrations of CDNB (1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene) and GSH in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. The reaction was monitored at 340 nm, ε=9600 M−1·cm−1. Apparent kinetic parameters, kcat, Km and kcat/Km were determined by fitting the collected data to a Michaelis–Menten equation by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) [8,12]. The cumene hydroperoxide assay was performed by the method of Wendel [13]. The inhibition studies were performed using the GST assay conditions of 3 mM CDNB and 10 mM GSH (except for adGSTD2-2 and adGSTD6-6, where 15 mM GSH was used) in the absence and presence of various concentrations of inhibitors. Inhibitor solutions were diluted appropriately to maintain a constant concentration of organic solvent, if used, when the inhibitor concentration was varied. Protein quantification was determined by the method of Bradford [14] using the Bio-Rad reagent with BSA as the standard protein.

Crystallization

Culture trays (Flow Laboratories, McLean, VA, U.S.A.) sealed with petroleum jelly and siliconized coverslips (Hampton Research, Laguna Niguel, CA, U.S.A.) were used to grow crystals by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The well contained a 1 ml solution containing 1.6–2 M Li2SO4, 1 mM CuCl2 and 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5–7.5. A 1 μl aliquot of protein (13.1 mg/ml), 1 μl of 10 mM glutathione sulphonic acid and 1 μl of well solution were applied to the bipyramidal crystals (0.1–0.2 mm) that appeared within 24 h of setting up the tray.

Data collection

Crystals were transferred to artificial mother liquor containing 20% (v/v) glycerol before snap-freezing at 100 K using an Oxford Cryo-Cooler. Data were collected using a Mar345 Image Plate system (marresearch GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) with Cu-Kα X-rays from a Rigaku Ru-200 rotating anode generator equipped with Ni-focusing mirrors.

Structure solution and refinement

The adGST1-6 (adGSTD6-6) monomer solved at 2.15 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) resolution (Protein Date Bank code 1V2A) was used as a search model for molecular replacement using Molrep [15]. All structure refinement was performed using CNS (Crystallography and NMR System) [16] and model building in O [17]. A random selection of 5% of reflections was chosen as a Free-R set to test the validity of various refinement steps. Alignment of adGSTD5-5 with adGSTD3-3 and adGSTD4-4 was performed using Deep View Swiss-PdbViewer version 3.7 (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) to obtain the RMSD (root mean square deviation) of the α-carbon backbone [18]. The Figures were created with Accelrys DS ViewerPro 5.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genomic organization and isolation of cDNA of adgstD5

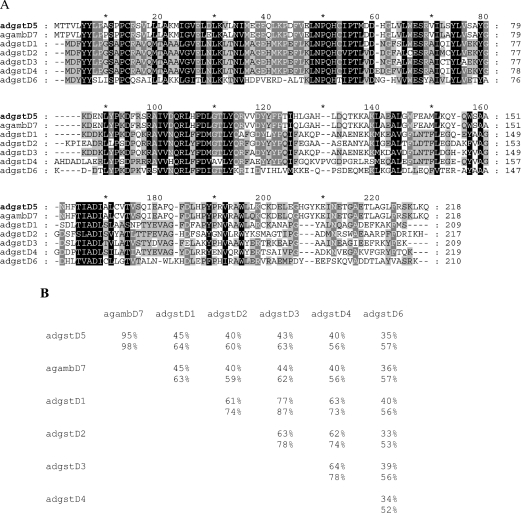

A BLAST analysis of the 15694 bp complete sequence of phage clone 8A.2 revealed a new GST gene, adgstD5, from the malaria vector A. dirus. This gene was named adgstD5 for A. dirus GST class Delta protein coding sequence 5. The adgstD5 gene is located upstream and is in reverse orientation to the adgst1AS1 gene (Figure 1). Previously, we had a partial sequence for the phage insert, which suggested that the second gene was downstream, as well as possibly of the same Delta class GST as adgst1AS1 and therefore was called gst1-5 for insect GST class one enzyme five [7]. The derived amino acid sequence of the three coding exons is shown in Figure 2. The BLAST analysis yielded the highest identity to aggst1-7 (now referred to as gstD7), the product of the aggst1β gene of Anopheles gambiae [19]. The percentage amino acid identity for these two enzymes is 95% and the percentage similarity is 98% (Figure 3). The two mosquito malaria vectors A. dirus and A. gambiae have been diverged for several million years, the first in Southeast Asia and the second in Africa. The high degree of sequence conservation between the two Anopheles species suggests that this GST isoenzyme has a role in the metabolism of a compound that is a common metabolic product or a significant component in the environment in many living cells. A comparison with the available A. gambiae genome data shows that the adGSTD5 protein has 29–45% amino acid identity with other Delta GSTs and 9–36% with GSTs from the remaining classes. The percentage amino acid similarity to the Delta GSTs is 49–66%. Therefore this GST is most like the Delta class GSTs; however, this gene encodes a singular GST protein with marginal amino acid identity with other Delta class GSTs.

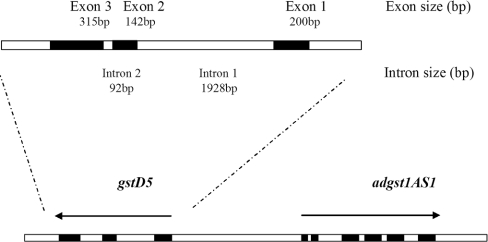

Figure 1. adgst1AS1 and gstD5 gene organization of 8A.2 clone.

The gstD5 gene is located 4620 bp upstream, with the opposite orientation to adgst1AS1. The 15694 bp genomic sequence has GenBank® accession number AF251478.

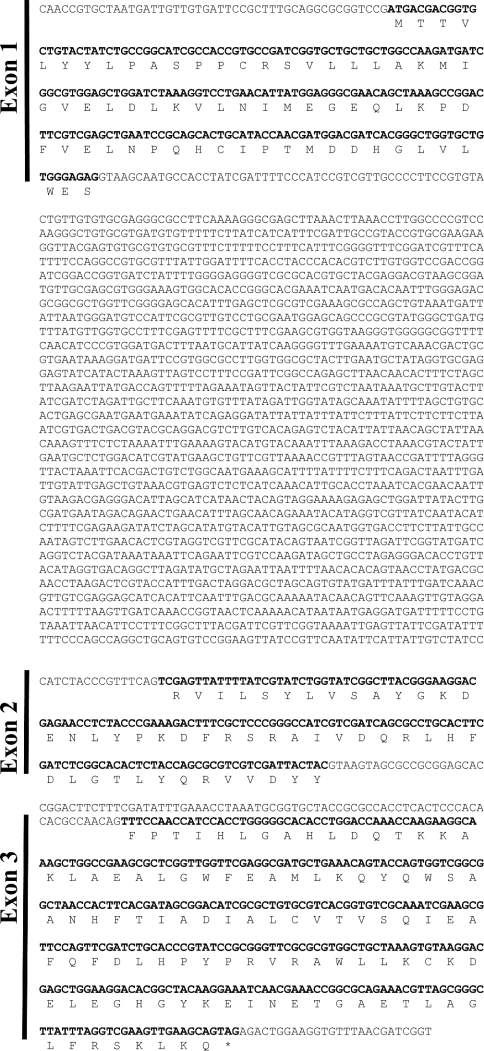

Figure 2. The gstD5 gene organization is composed of three coding regions that code for one GST protein.

The coding sequence is shown in bold, with the translated amino acid sequence below. The last codon of exon 1 is split, with the last base of the codon in exon 2.

Figure 3. Amino acid sequence comparison of A. dirus adGSTD5-5 and the orthologous enzyme of AgGSTD7 from A. gambiae (agambD7) and five previously obtained A. dirus Delta GSTs using GeneDoc version 2.6.

The sequences are adGSTD1-1, adGSTD2-2, adGSTD3-3, adGSTD4-4 and adGSTD6-6 (GenBank® accession numbers AF273041, AF273038, AF273039, AF273040 and AY014406 respectively [6,8]). (A) The dashes indicate gaps in the sequence. Black shading indicates 100% conserved residues for the seven sequences, dark grey indicates 80% conserved, and light grey indicates 60% conserved. (B) Matrix table of percentage amino acid identities (top value) and percentage amino acid similarities (bottom value) for the sequences aligned in (A).

Putative promoters of adgstD5

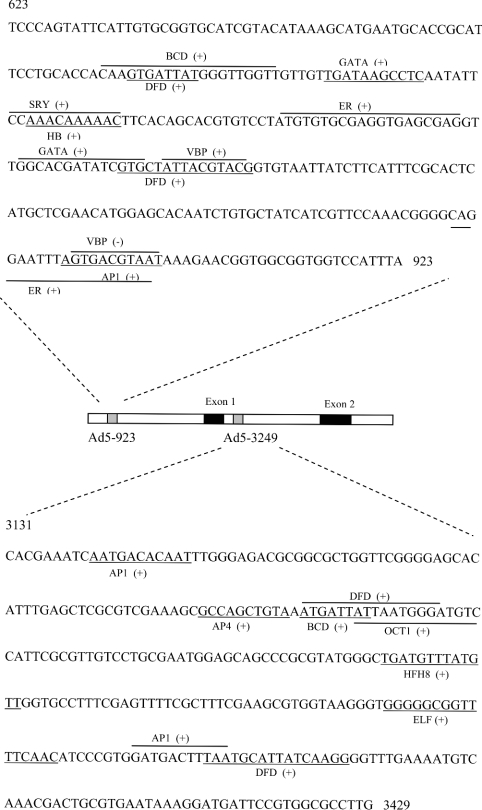

Previously, intronless GST genes have been reported in Drosophila; however, later introns were identified, as well as a 5′ untranslated region exon [20]. Our data of the exon composition of adgstD5 define only the coding region. An additional possible 5′ and 3′ splice site were identified by BCM Gene Finder [21]. This suggests a possible 5′ splice site (TG/GTGGTT) and 3′ splice site (TTGCAG/GC) (bold indicates the usually conserved splice site codon cleavage points) 771 bp and 11 bp upstream of exon 1 respectively. This implies that there is an exon that may be a 5′ untranslated region. Analysis also revealed two putative promoters, Ad5-923 and Ad5-3429, which may be defined as regulatory promoters of adgstD5, and are required to fulfil the core promoter activity in specific physiological circumstances (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Sequence of two putative promoters of gstD5 (Ad5-923 and Ad5-3429).

Potential transcription-factor-binding sites were mapped on the region of these two putative promoters by the MatInspector program. BCD, bicoid; ELF, grainyhead protein of Drosophila; ER, oestrogen receptor; HFH8, forkhead domain protein; SRY, sex-determining region Y; VBP, vitellogenin-binding protein. The binding site of each potential transcription factor is underlined or overlined. The (+) indicates the binding site on the sense strand, while (−) indicates the binding site on the antisense strand.

Ad5-923 contains several binding sites for developmentally regulated transcription factors, such as hunchback, Dfd, AP-1 (activator protein 1) and GATA-1 (Figure 4). Also of interest are several binding sites of oestrogen receptor and oestrogen-dependent protein (oestrogen-receptor- and vitillogenin-binding protein) and maternal-effect protein in Ad5-923. It has been reported that there is an oestrogen-like compound in another arthropod, the ovary of shrimp (Parapenaeus fissurus) [22]. Searching the Drosophila genome database for an oestrogen receptor sequence yielded one sequence (CG 7404 gene product) on chromosome 3 that was distinct from the ecdysone receptor gene which is located on chromosome 2. BLAST analysis of the CG 7404 gene product provided the highest score to an oestrogen-related receptor β (41% identity and 53% similarity). These data imply that oestrogen-like compounds in insects may function in a similar way to vertebrate oestrogen. It is possible that the type of transcription factor binding sites detected in Ad5-293 may have contributed to the specific expression of Adgst5 mRNA in adult female mosquitoes.

Oocyte development in female mosquitoes involves lipid synthesis at extra-ovarian sites, such as the fat body, transfer and then incorporation into oocytes [23,24]. In Aedes aegypti, the dry weight of oocytes consists of 35% lipids, 80% of which has been transported from fat body [23,24]. The accumulation and transport of the lipid reserves in adult female mosquitoes would create an oxidative stress burden that could be alleviated by increased GST expression. The presence of an oestrogen-response element upstream of the GSTA gene was proposed to have a possible role in sexually maturing female plaice oocyte development [25]. The authors suggested that the enormous mobilization of lipids during lipovitellin synthesis in females presents a specific requirement of a GST-mediated detoxification mechanism to deal with lipid peroxidation, since up to 50% of total fish egg lipid is composed of polyunsaturated fatty acids originating from the mother [25]. Ad5-923 contained both the oestrogen-response element and a vitellogenin-binding-protein element, which suggests that adgstD5 might be involved in oogenesis, as was proposed for the fish GST.

Currently, the number of genes known to be regulated by elements outside the 5′ flanking region is constantly increasing. These intronic regulators often direct cell-type-specific or developmentally regulated gene expression [26]. Ad5-3429 is located within the intron, and contains several binding sites for factors that are reported to be involved in embryo or tissue development; that is, bicoid, HFH8, Elf, oct, dfd and AP-1 (Figure 4). This putative promoter therefore may be involved in developmental-stage regulation.

Expression and characterization of the recombinant adGSTD5-5 enzyme

Induction of the E. coli culture gave a high yield of recombinant adGSTD5-5 protein expression (250–300 mg/l of E. coli culture). However, adGSTD5-5 had a very weak affinity for GST-affinity chromatography medium compared with other GST isoenzymes from A. dirus, so the final yield of purified GST was low (1–3 mg/l of E. coli culture).

The characterization of the recombinant adGSTD5-5 was intrinsically problematic, as the enzyme possessed low detectable activities, suggesting the enzyme possessed very different substrate specificities compared with the other A. dirus GSTs. The adGSTD5-5 enzyme had an intermediate specific activity in GSH conjugation with the classical GST substrate CDNB. The Km for GSH was the lowest observed for all six A. dirus GSTs (Table 1), suggesting the highest affinity binding to GSH. An estimated Vmax of 167 μmol/min per mg and Km of 14.9 mM are given only for purposes of comparison, as the data was collected well below the Km value owing to CDNB solubility limits. The fairly high Km for CDNB indicated low-affinity binding for this substrate. Cumene hydroperoxide activity was measured for adGSTD5-5 and also, for comparison, adGSTD4-4. The adGSTD5-5 activity of 0.293±0.004 μmol/min per mg of protein (mean±S.D.) was 6-fold greater than the 0.050±0.009 μmol/min per mg of protein determined for adGSTD4-4. Our study of a range of compounds shown previously to be substrates for cytosolic GSTs from the classes described previously, including 1,2-dichloro-4-nitrobenzene, p-nitrophenethyl bromide and ethacrynic acid, revealed that there was no detectable activity with these known GST substrates, even at 10-fold increased enzyme concentration compared with that used in the CDNB assay. Nevertheless, adGSTD5-5 did interact with these substrates as well as pyrethroid insecticides, as shown by inhibition of CDNB activity (Table 2). Intriguingly, only adGSTD5-5 was inhibited by dichloroacetic acid, which is the specific substrate for Zeta class GSTs in dechlorination of dichloroacetic acid to glyoxylic acid [27–31]. However, this dechlorination activity was undetectable for adGSTD5-5. Despite low GSH-conjugating activity, adGSTD5-5 possessed the greatest DDT [1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(p-chlorophenyl)ethane] dehydrochlorination activity of the six recombinant GSTs that we have currently obtained (Table 3). The DDTase activity was 11–62-fold different among the five A. dirus GSTs, and adGSTD1-1 had no detectable activity (Table 3). A ratio of DDTase/CDNB activity showed that the adGSTD5-5 enzyme possessed a 4–100-fold greater DDT substrate preference compared with the other GSTs. Altogether, these data illustrate that adGSTD5-5 displays catalytic properties distinct from the insect GST isoenzymes defined previously. Two additional classes of soluble GSTs, Omega and Zeta, were also described recently with unusual enzymatic activities in a variety of organisms, including mammals [32–34]. This suggests that gene rearrangement in combination with structural evolution presumably constitutes an evolutionary function of the GST enzymes operating in Nature [35]. The mechanism of catalysis and the residues involved are yet to be investigated for adGSTD5-5.

Table 1. Kinetic parameters of A. dirus GSTs.

The data for adGSTD1-1, adGSTD2-2, adGSTD3-3, adGSTD4-4 and adGSTD6-6 have been reported previously [6,8,11].

| CDNB | GSH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoenzyme | Vmax (μmol/min per mg) | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (mM−1·s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (mM−1·s−1) |

| adGSTD5-5 | 167±48 | 69 | 14.9±4.9 | 5 | 0.21±0.01 | 400 |

| adGSTD1-1 | 12.9±0.6 | 5.03 | 0.10±0.03 | 48.4 | 0.86±0.2 | 5.86 |

| adGSTD2-2 | 63.9±3.50 | 25.9 | 0.21±0.03 | 121 | 1.30±0.15 | 20 |

| adGSTD3-3 | 67.5±1.97 | 26.9 | 0.10±0.01 | 269 | 0.40±0.05 | 67 |

| adGSTD4-4 | 40.3±1.89 | 16.9 | 0.52±0.67 | 32 | 0.83±0.08 | 20 |

| adGSTD6-6 | 2.2±0.3 | 0.9 | 5.3±0.8 | 0.2 | 1.8±0.4 | 0.5 |

Table 2. Inhibition study of CDNB activity.

The CDNB activity was measured in the absence and presence of the respective compound at the concentration given. The data presented represent the means±S.D. for at least three independent experiments. ND, not detected.

| Inhibition (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Concentration (mM) | adGSTD5-5 | adGSTD1-1 | adGSTD2-2 | adGSTD3-3 | adGSTD4-4 | adGSTD6-6 |

| Dichloroacetic acid | 0.5 | 16.84±3.22 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Cumene hydroperoxide | 2.5 | 37.17±1.19 | 30.36±9.53 | 60.44±2.15 | 28.94±4.82 | 29.53±3.77 | 28.27±2.56 |

| p-Nitrobenzyl chloride | 1.0 | 33.40±6.07 | 43.38±5.17 | 37.60±3.67 | 55.36±1.84 | 49.77±1.35 | 9.52±1.98 |

| p-Nitrophenyl bromide | 0.1 | 35.72±1.50 | 24.30±14.52 | 17.28±0.88 | 33.39±3.78 | 31.33±3.10 | 3.17±3.85 |

| Ethacrynic acid | 0.1 | 84.67±0.71 | 100±0 | 99.57±0.59 | 98.31±0.10 | 100±0 | 86.36±1.65 |

| 0.01 | 55.22±0.66 | 99.46±1.54 | 94.88±1.32 | 81.61±0.76 | 85.49±1.58 | 57.73±3.09 | |

| 0.001 | 40.28±3.16 | 81.88±4.14 | 64.16±3.74 | 37.95±1.99 | 46.45±3.39 | 37.55±1.40 | |

| S-Hexylglutathione | 0.1 | 71.98±1.76 | 94.93±0.65 | 97.08±0.92 | 67.84±1.10 | 76.91±0.26 | 64.14±3.58 |

| 0.01 | 24.87±3.93 | 63.18±3.21 | 75.44±0.61 | 32.07±1.58 | 20.09±1.24 | 35.03±2.46 | |

| Permethrin | 0.01 | 35.56±1.68 | 20.37±1.90 | 27.36±5.45 | 35.87±1.87 | 47.73±3.08 | 11.70±1.87 |

| Deltamethrin | 0.01 | 40.15±2.17 | 11.01±7.51 | 30.72±3.53 | 35.28±3.05 | 49.30±2.37 | 15.87±5.29 |

| λCyhalothrin | 0.01 | 39.96±1.19 | 21.88±10.66 | 29.11±2.88 | 26.38±1.73 | 40.50±1.40 | 23.26±5.58 |

Table 3. DDTase activity of the recombinant GST isoenzymes from A. dirus.

The DDTase activity is expressed as nmol of DDE (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene) formation/mg of enzyme protein. The CDNB specific activity is in μmol/min per mg of protein.

| Isoenzyme | DDTase activity | CDNB activity | DDTase/CDNB |

|---|---|---|---|

| adGSTD5-5 | 78.77±13.19 | 19.2 | 4.11 |

| adGSTD1-1 | <1.0 | 12.2 | – |

| adGSTD2-2 | 1.87±0.82 | 39.7 | 0.05 |

| adGSTD3-3 | 2.66±0.29 | 64.6 | 0.04 |

| adGSTD4-4 | 7.50±1.68 | 38.3 | 0.20 |

| adGSTD6-6 | 1.28±0.22 | 1.37 | 0.93 |

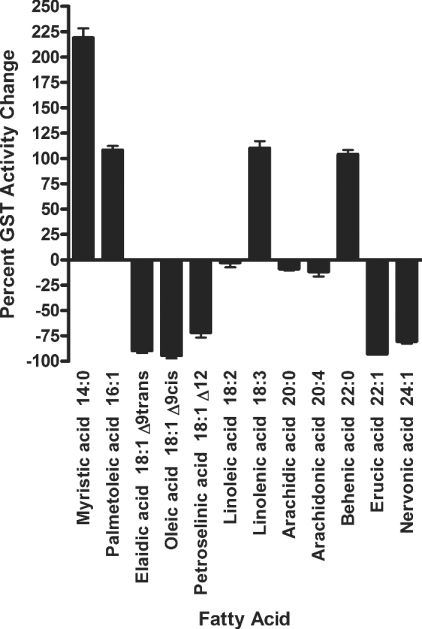

Various mammalian GST isoforms have been shown to be highly active in conjugating toxic lipid alkenals and purine and pyrimidine alkenals, all of which are believed to arise in cells as a consequence of oxidative processes [36,37]. Interestingly, adGSTD5-5 contained the putative regulatory elements involved in detoxification of lipid peroxidation. Therefore we investigated the role of heterologously expressed adGSTD5-5 involved in detoxification of potentially deleterious fatty acid metabolites by assaying the effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on GSH conjugation with CDNB. Our data demonstrated adGSTD5-5 interaction with several fatty acids (Figure 5). An interesting observation was that, although several fatty acids appeared to have little effect on CDNB activity, the others tested either inhibited activity by 72–94% or enhanced activity by 104–219%. This fatty acid interaction yielding various effects on adGSTD5-5 implies that adGSTD5-5 may have a physiological role in protection against oxidative stress as reported previously for GST Alpha class isoenzymes that appear to be involved in the signalling mechanisms of apoptosis [38].

Figure 5. Fatty acid effects on adGSTD5-5 CDNB activity.

The final concentration of fatty acids tested was 50 μM in the standard CDNB assay. Data show the changed enzyme activity for CDNB in the presence of the respective fatty acid, where negative values show inhibition and positive values show activation relative to the absence of any fatty acid.

Structural determination of the adGSTD5-5 enzyme

Molecular replacement was successful with the solution corresponding to the highest peak in the rotation function (5.97σ) and translation function (13.82σ) as shown in Table 4. The initial model (R-factor=0.526, R-free=0.515) was subjected to rigid body, positional and temperature-factor refinement, reducing the R-factor to 0.466 (R-free=0.485). Sigma-A weighted 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc electron density maps calculated from this model revealed a molecule in the G-site not present in the model. This was clearly a glutathione sulphonic acid molecule. Six cycles of positional refinement, B-factor refinement and model building were performed in which the amino acid sequence of the model was changed from that of adGSTD6-6 to adGSTD5-5. The final model includes amino acid residues 2–215, one glutathione sulphonic acid molecule and 44 water molecules. Statistics for this model are given in Table 5. The adGSTD5-5 structure obtained for this study is shown in Figure 6 (Protein Data Bank accession number 1R5A).

Table 4. X-ray data reduction statistics.

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution bin (2.59–2.50 Å).

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| R-factor (%) | 7.8 (39.6) |

| I/σI | 12.9 (2.6) |

| Number of observations | 37582 (3682) |

| Number of unique observations | 9605 (963) |

| Multiplicity | 3.9 (3.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.6 (97.9) |

Table 5. Model statistics.

Values in parentheses refer to the highest resolution bin (2.66–2.50 Å).

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| R-factor | 0.233 (0.351) |

| R-free | 0.265 (0.407) |

| Non-hydrogen atoms in model: | |

| Protein | 1732 |

| Glutathione sulphonic acid | 23 |

| Water | 44 |

| Cu2+ ions | 3 |

| Mean B-factor | 45.5 |

| B-factor from Wilson plot | 41.8 |

| RMSD from ideal values | |

| Bond lengths | 0.007 Å |

| Bond angles | 1.4° |

| Dihedral angles | 20.8° |

| Improper angles | 0.82° |

Figure 6. Stereo view of adGSTD5-5.

The view is looking down on the 2-fold axis into the active site, with the glutathione sulphonic acid shown as a ball-and-stick figure. The co-ordinates for the tertiary structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 1R5A.

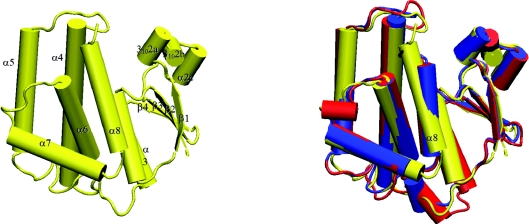

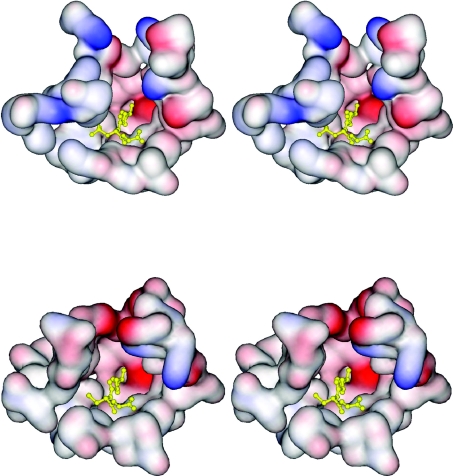

The tertiary structure obtained from crystallographic analysis showed the adGSTD5-5 protein to possess the canonical GST structure (Figure 7). The physiologically relevant state of the protein is a dimer, which is present in the crystal owing to a 2-fold symmetry operation. The overall structure is broadly similar to that of previously determined Delta class GST structures [5]. The G-site is formed mostly by residues from the N-terminal thioredoxin domain. Like other Delta class GSTs, a serine residue (Ser11) appears to be responsible for activating the GSH thiol residue in catalysis. However, in the absence of direct evidence such as site-directed mutagenesis, it is possible that a nearby serine, cysteine or tyrosine residue may be the major catalytic residue. The presence of a histidine residue (His119) was unexpected: GST H-sites normally being lined with hydrophobic residues. A water molecule sits in the H-site and is hydrogen-bonded to His119Nε2. An alignment of the adGSTD5-5 tertiary structure with these two A. dirus GSTs, adGSTD3-3 and adGSTD4-4 (Protein Data Bank accession numbers 1JLV and 1JLW respectively), illustrates the conserved nature of GST tertiary structure. adGSTD5-5 possessed an RMSD of 1.42 Å and 1.25 Å for the α-carbon alignment with adGSTD3-3 and adGSTD4-4 respectively. There are significant differences between the packing of helix α8 of adGSTD5-5 with the rest of the protein. As a result, this helix is closer to the C-terminal domain compared with other insect GST isoenzymes (Figure 7). This can be attributed to the replacement of packing residues in adGSTD5-5 by smaller amino acids. As such, the overall shape of the H-site is different in adGSTD5-5 compared with the adGSTD3-3 and adGSTD4-4 isoenzymes. A comparison of adGSTD5-5 and adGSTD3-3 showed 47% identity in the 43 amino acids that make up the active-site pocket with an average RMSD of 0.616 Å for the identical amino acid residues. However, the shape of the two active-site pockets seems to be quite distinct, with the adGSTD5-5 pocket appearing to be elongated (Figure 8). In comparison, the adGSTD5-5 pocket also appears to be more polar, with an increase in both positive and negative charges that contributes to distinct orientations of GSH and substrate binding. These structurally unique features of adGSTD5-5, especially in the vicinity of the active site and the C-terminus, may define the substrate repertoire for this particular GST, whereby it displays an unusual enzymatic property. These results suggest that there is considerable structural plasticity in the active site of Delta class GSTs, and that their catalytic activities may not be restricted to hydrophobic co-substrates.

Figure 7. Cartoon representation of adGSTD5-5.

Cylinders represent helices, arrows represent strands, and lines represent random coil. Left: adGSTD5-5, with secondary structure elements labelled. Right: Aligned Anopheles GSTs. adGSTD3-3 is in blue, adGSTD4 is in red, and adGSTD5-5 is in yellow.

Figure 8. Stereo views of the electrostatic potential surface of the active-site pockets of adGSTD5-5 and adGSTD3-3.

The two tertiary structures were aligned to illustrate the same view of the active site. The top panel shows adGSTD5-5, and the bottom panel shows adGSTD3-3. A yellow ball-and-stick representation shows the GSH in the pocket.

Conclusion

The adGSTD5-5 isoenzyme was identified and only detectably expressed in A. dirus adult females. A high degree of sequence conservation of this gene across several million years of divergent evolution between two Anopheline malaria vector species suggests that this GST isoenzyme performs an important function. A putative promoter analysis suggests that this GST has an involvement in oogenesis and in developmental-stage regulation. The enzyme displayed little activity for classical GST substrates, although it possessed the greatest activity for DDT, 10-fold, observed for Delta GSTs. However enzyme activity was increased or decreased by fatty acid interaction, suggesting that the GST activity may be modulated by fatty acids. A tertiary structure comparison revealed differences in active-site composition, with an elongated and more polar active-site topology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Thailand Research Fund, and R.U. was supported by a Royal Golden Jubilee Scholarship.

References

- 1.Ding Y., Ortelli F., Rossiter L. C., Hemingway J., Ranson H. The Anopheles gambiae glutathione transferase supergene family: annotation, phylogeny and expression profiles. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:35–50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vontas J. G., Small G. J., Hemingway J. Glutathione S-transferases as antioxidant defence agents confer pyrethroid resistance in Nilaparvata lugens. Biochem. J. 2001;357:65–72. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou S., Meadows S., Sharp L., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. Genome-wide study of aging and oxidative stress response in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:13726–13731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260496697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prapanthadara L., Hemingway J., Ketterman A. J. Partial purification and characterization of glutathione S-transferases involved in DDT resistance from the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1993;47:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakley A. J., Harnnoi T., Udomsinprasert R., Jirajaroenrat K., Ketterman A. J., Wilce M. C. J. The crystal structures of glutathione S-transferases isozymes 1–3 and 1–4 from Anopheles dirus species B. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2176–2185. doi: 10.1110/ps.ps.21201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jirajaroenrat K., Pongjaroenkit S., Krittanai C., Prapanthadara L., Ketterman A. J. Heterologous expression and characterization of alternatively spliced glutathione S-transferases from a single Anopheles gene. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001;31:867–875. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pongjaroenkit S., Jirajaroenrat K., Boonchauy C., Chanama U., Leetachewa S., Prapanthadara L., Ketterman A. J. Genomic organization and putative promoters of highly conserved glutathione S-transferases originating by alternative splicing in Anopheles dirus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udomsinprasert R., Ketterman A. J. Expression and characterization of a novel class of glutathione S-transferase from Anopheles dirus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;32:425–433. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannervik B., Awasthi Y. C., Board P. G., Hayes J. D., Di Ilio C., Ketterer B., Listowsky I., Morgenstern R., Muramatsu M., Pearson W. R., et al. Nomenclature for human glutathione transferases. Biochem. J. 1992;282:305–306. doi: 10.1042/bj2820305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chelvanayagam G., Parker M. W., Board P. G. Fly fishing for GSTs: a unified nomenclature for mammalian and insect glutathione transferases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;133:256–260. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ketterman A. J., Prommeenate P., Boonchauy C., Chanama U., Leetachewa S., Promtet N., Prapanthadara L. Single amino acid changes outside the active site significantly affect activity of glutathione S-transferases. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001;31:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prapanthadara L., Koottathep S., Promtet N., Hemingway J., Ketterman A. J. Purification and characterization of a major glutathione S-transferase from the mosquito Anopheles dirus (species B) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996;26:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(95)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wendel A. Glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1981;77:325–333. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(81)77046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vagin A., Teplyakov A. An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2000;56:1622–1624. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900013780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Gross-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guex N., Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranson H., Collins F., Hemingway J. The role of alternative mRNA splicing in generating heterogeneity within the Anopheles gambiae class I glutathione S-transferase family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:14284–14289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lougarre A., Bride J. M., Fournier D. Is the insect glutathione S-transferase I gene family intronless? Insect Mol. Biol. 1999;8:141–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.810141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith R., Wiese B., Wojzynski M., Davison D., Worley K. BCM search launcher – an integrated interface to molecular biology data base search and analysis services available on the World Wide Web. Genome Res. 1996;6:454–462. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeng S. S., Wan W. C., Chang C. F. Existence of an estrogen-like compound in the ovary of the shrimp Parapenaeus fissurus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1978;36:211–214. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegler R., Ibrahim M. M. Formation of lipid reserves in fat body and eggs of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J. Insect Physiol. 2001;47:623–627. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briegel H., Gut T., Lea A. O. Sequential deposition of yolk components during oogenesis in an insect, Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Insect Physiol. 2003;49:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(02)00272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leaver M. J., Wright J., George S. G. Structure and expression of a cluster of glutathione S-transferase genes from a marine fish, the plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) Biochem. J. 1997;321:405–412. doi: 10.1042/bj3210405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warnecke C., Willich T., Holzmeister J., Bottari S. P., Fleck E. Efficient transcription of the human angiotensin II type 2 receptor gene requires intronic sequence elements. Biochem. J. 1999;340:17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson W. B., Board P. G., Gargano B., Anders M. W. Inactivation of glutathione transferase zeta by dichloroacetic acid and other fluorine-lacking α-haloalkanoic acids. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:1144–1149. doi: 10.1021/tx990085l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong Z., Board P. G., Anders M. W. Glutathione transferase zeta catalyses the oxygenation of the carcinogen dichloroacetic acid to glyoxylic acid. Biochem. J. 1998;331:371–374. doi: 10.1042/bj3310371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzeng H.-F., Blackburn A. C., Board P. G., Anders M. W. Polymorphism- and species-dependent inactivation of glutathione transferase zeta by dichloroacetate. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:231–236. doi: 10.1021/tx990175q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thom R., Dixon D. P., Edwards R., Cole D. J., Lapthorn A. J. The structure of a Zeta class glutathione S-transferase from Arabidopsis thaliana: characterisation of a GST with novel active-site architecture and a putative role in tyrosine catabolism. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:949–962. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polekhina G., Board P. G., Blackburn A. C., Parker M. W. Crystal structure of maleylacetoacetate isomerase/glutathione transferase zeta reveals the molecular basis for its remarkable catalytic promiscuity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1567–1576. doi: 10.1021/bi002249z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Board P. G., Coggan M., Chelvanayagam G., Easteal S., Jermiin L. S., Schulte G. K., Danley D. E., Hoth L. R., Griffor M. C., Kamath A. V., et al. Identification, characterization, and crystal structure of the omega class glutathione transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24798–24806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anders M. W., Anderson W. B., Tzeng H.-F., Board P. G. Glutathione transferase zeta: novel xenobiotic substrates and enzyme inactivation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;133:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Board P., Baker R. T., Chelvanayagam G., Jermiin L. S. Zeta, a novel class of glutathione transferases in a range of species from plants to humans. Biochem. J. 1997;328:929–935. doi: 10.1042/bj3280929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker M. W., McKinstry W. J., Oakley A. J., Polekhina G., Rossjohn J., Chelvanayagam G., Board P. G., Di Ilio C., Caccuri A. M., Ricci G., Lo Bello M. Evolution of functional diversity as observed through structural studies of glutathione transferases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;133:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berhane K., Widersten M., Engström Å., Kozarich J. W., Mannervik B. Detoxication of base propenals and other α,β-unsaturated aldehyde products of radical reactions and lipid peroxidation by human glutathione transferases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:1480–1484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishikawa T., Esterbauer H., Sies H. Role of cardiac glutathione transferase and of the glutathione S-conjugate export system in biotransformation of 4-hydroxynonenal in the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:1576–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y., Cheng J.-Z., Singhal S. S., Saini M., Pandya U., Awasthi S., Awasthi Y. C. Role of glutathione S-transferases in protection against lipid peroxidation: overexpression of hGSTA2–2 in K562 cells protects against hydrogen peroxide induced apoptosis and inhibits JNK and caspase 3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19220–19230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]