Abstract

We have investigated effects of neuronal differentiation on hormone-induced Ca2+ entry. Fura-2 fluorescence measurements of undifferentiated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells, stimulated with methacholine, revealed the presence of voltage-operated Ca2+-permeable, Mn2+-impermeable entry pathways, and at least two voltage-independent Ca2+- and Mn2+-permeable entry pathways, all of which apparently contribute to both peak and plateau phases of the Ca2+ signal. Similar experiments using 9-cis retinoic acid-differentiated cells, however, revealed voltage-operated Ca2+-permeable, Mn2+-impermeable channels, and, more significantly, the absence or down-regulation of the most predominant of the voltage-independent entry pathways. This down-regulated pathway is probably due to CCE (capacitative Ca2+ entry), since thapsigargin also stimulated Ca2+ and Mn2+ entry in undifferentiated but not differentiated cells. The Ca2+ entry components remaining in methacholine-stimulated differentiated cells contributed to only the plateau phase of the Ca2+ signal. We conclude that differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells results in a mechanistic and functional change in hormone-stimulated Ca2+ entry. In undifferentiated cells, voltage-operated Ca2+ channels, CCE and NCCE (non-CCE) pathways are present. Of the voltage-independent pathways, the predominant one appears to be CCE. These pathways contribute to both peak and plateau phases of the Ca2+ signal. In differentiated cells, CCE is either absent or down-regulated, whereas voltage-operated entry and NCCE remain active and contribute to only the plateau phase of the Ca2+ signal.

Keywords: capacitative Ca2+ entry, differentiation, methacholine, neuroblastoma cell, retinoic acid, SH-SY5Y cell

Abbreviations: CCE, capacitative calcium entry; 9cRA, 9-cis retinoic acid; MeCh, methacholine; NCCE, non-CCE; TRP, transient receptor potential; VOC, voltage-operated Ca2+ channel; VOCI, voltage-operated Ca2+ channel inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Changes in [Ca2+]i (intracellular free Ca2+ concentration) form an integral part of the signalling mechanisms underlying many fundamental cellular processes in both electrically excitable and non-excitable cells [1]. Such intracellular Ca2+ signals are often temporally and spatially complex [2]. In order that these signals may be generated and maintained, cells call upon a ‘toolkit’ of signalling components, the combination of which can result in a Ca2+ signal with distinct temporal and spatial characteristics [3]. For example, intracellular Ca2+ signals, stimulated by external stimuli which hydrolyse phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, usually consist of two temporal phases – an initial peak phase reflecting release from InsP3 (inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate)-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ stores followed by an elevated plateau phase reflecting Ca2+ entry from the external medium [4]. Although the role of InsP3 in mediating Ca2+ mobilization from intracellular stores is established [1], the links between receptor-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis and Ca2+ entry are less clear. One Ca2+ entry pathway that is particularly well studied is the CCE (capacitative Ca2+ entry) pathway, where substantial evidence suggests that empty stores provide a signal that activates Ca2+ entry [4,5], though the signal is yet to be identified [6]. However, it is becoming increasingly evident that alternative pathways of agonist-stimulated Ca2+ entry also operate in many cell types [7], including so-called NCCE (non-CCE) pathways [5]. Some of these are activated through the other limb of the phosphoinositide pathway; e.g. by diacylglycerol [5,8] or arachidonic acid [9–12]. The physiological roles of these different pathways are yet to be determined [5,7].

The SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, which displays many characteristics of sympathetic ganglion cells, has been widely used in the investigation of a variety of Ca2+ signalling pathways, including voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and phosphoinositide hydrolysis [13–18]. Furthermore, these cells can be differentiated morphologically and biochemically to a more neuronal-like phenotype in response to agents such as retinoids [19,20] and phorbol esters [19]. SH-SY5Y cells therefore represent an ideal system to study not only the function of specific Ca2+ signalling toolkit components, but also to study how that function may change as the cells undergo a physical change towards a more neuronal phenotype. Previous studies have reported that retinoid-induced differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells results in an increase in both the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density [14] and in the magnitude of the hormone-induced production of InsP3 [18]. Ca2+ signalling proteins, such as the type 1 InsP3 receptor and type 2 ryanodine receptor, however, appear to be present at equal levels in both undifferentiated and differentiated cells [17].

In the present study, we have examined the effects of retinoid-induced differentiation on hormone-stimulated Ca2+ entry. The results reveal that differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells is accompanied by a change in the mechanism of hormone-induced Ca2+ entry. In undifferentiated cells there appears to be voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry, and at least two voltage-independent Ca2+ entry pathways, the predominant one of which is probably classical CCE. In retinoid-differentiated cells, CCE appears to be either absent or down-regulated, while the second (NCCE) pathway and the voltage-operated pathways remain active. Furthermore, these mechanistic changes are shown to be functionally significant, since the contribution of the Ca2+ entry component to the overall hormone-induced Ca2+ signal also changes on differentiation. The alteration in the mechanism of hormone-induced Ca2+ entry observed on differentiation may represent a variation on the ‘reciprocal regulation’ theme of CCE and NCCE pathways [5,10–12,21]. Some aspects of this work have been published in abstract form [22,23].

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

SH-SY5Y cells were kindly supplied by R. Ross (Fordham University, NY, U.S.A.). Fura-2 AM, thapsigargin, verapamil and ω-conotoxin GVIA were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). All other chemicals and tissue culture reagents were obtained from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, U.K.).

Cell culture and differentiation

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with foetal calf serum (10%, v/v), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 IU·ml−1) and streptomycin (100 IU·ml−1), at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2). For DIC microscopy, cells were seeded on 22 mm×40 mm glass coverslips; for measurements of [Ca2+]i and Mn2+ quench of fura-2, cells were seeded on 22 mm×40 mm or 10 mm diameter glass coverslips. Cells were passaged once a week and not used beyond passage 28.

For differentiation, cells were seeded on to coverslips at approx. 10% confluency and differentiation initiated by the addition of 1 μM 9cRA (9-cis retinoic acid). Differentiation media was then replaced every 2 days. Cells were used 7 days after the start of treatment. Control cells were treated identically but with vehicle (ethanol) added to the media in place of 9cRA. To assess the degree of differentiation, coverslips were mounted on the stage of a Zeiss Axiovert 200M.

Determination of [Ca2+]i in cell populations

[Ca2+]i was measured in confluent monolayers of SH-SY5Y cells using the Ca2+-sensitive dye, fura-2, in a variation of the methodology used for PC12 cells [24]. Cells were washed in Krebs buffer (118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 200 μM sulphinpyrazone and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) and loaded with fura-2 by incubation in a solution of 3 μM fura-2 AM in Krebs buffer for 45 min at 37 °C. This solution was then replaced with unsupplemented Krebs and the incubation continued for a further 60 min at 37 °C, to allow de-esterification of the loaded dye. Single coverslips were mounted in a coverslip holder (PerkinElmer, Beaconsfield, U.K.), which was inserted into a stirred thermostatted cuvette maintained at 37 °C. Before commencing each experiment, an excitation wavelength scan (300–400 nm) was performed to reveal any large inconsistency in the degree of confluency and/or dye loading. Less than 1% of coverslips were rejected on this basis. Fura-2 fluorescence was continuously monitored using a PerkinElmer LS-50B fluorimeter, with excitation and emission wavelengths of 340 and 510 nm respectively. When performing Mn2+ quench experiments, excitation and emission wavelengths were 360 and 510 nm respectively.

[Ca2+]i were calculated using the PerkinElmer WinLab software which uses the formula of Grynkiewicz et al., assuming a dissociation constant Kd of 224 nM at 37 °C [25]. Fmax (maximum fura-2 fluorescence) was obtained by the addition of 50 μM ionomycin and Fmin (minimum fura-2 fluorescence) was indirectly obtained by the addition of 1 mM MnCl2 to obtain FMn (fluorescence after quenching of fura-2). Fmin was then calculated using the equation:

|

In situ calibrations were performed for each individual experiment to account for individual variation in confluency and/or fura-2-loading. All other calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software for Science, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

For experiments in nominally Ca2+-free Krebs buffer, fura-2-loaded cells were washed with Krebs buffer without 2 mM CaCl2 and this same buffer was used in the cuvette.

For Mn2+ quench experiments, cells were exposed to 100 μM MnCl2 in Krebs buffer. First-order rate constants for the quench of fura-2, reflecting the rate of Mn2+ entry, were calculated by fitting single exponential decay curves to quench traces [24], such as those illustrated in Figure 6.

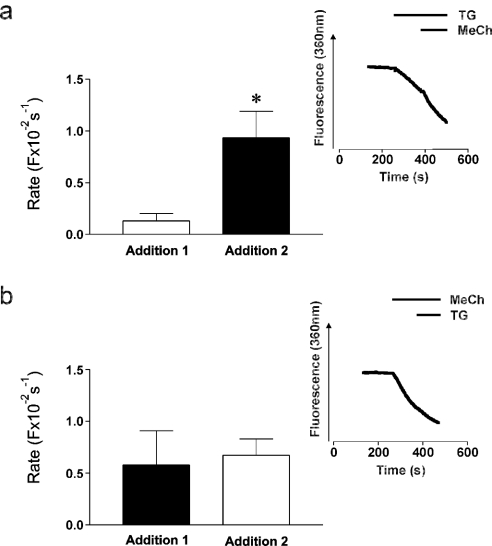

Figure 6. Mn2+-quench reveals an additional entry component stimulated by MeCh in undifferentiated cells.

Fura-2-loaded undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells were stimulated with MeCh or thapsigargin (‘Addition 1’) in the presence of 100 μM Mn2+ and the subsequent quench of fura-2 fluorescence monitored at 360 nm excitation. This was followed by the addition of the second agonist (‘Addition 2’). (a) Sequential addition of 200 nM thapsigargin (□) followed by 1 mM MeCh (■). (b) Sequential addition of 1 mM MeCh (■) followed by 200 nM thapsigargin (□). Bars show averaged first-order rate constants for the quench of fura-2 obtained by fitting single-exponential decay curves to quench traces, such as those shown in the insets. Data are means±S.E.M., n=5. * indicates significant deviation from the rate constant stimulated by the first addition (P=0.02).

Determination of [Ca2+]i in single cells

Coverslips were loaded with fura-2 AM as described for cell populations and then mounted on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot inverted epi-fluorescence microscope. Fura-2 fluorescence was excited by alternate excitation at 340 and 380 nm using a high-speed random access monochromator (Photon Technology International, West Sussex, U.K.) and a xenon arc lamp (75 W). Emitted light collected by the objective was passed through a dichroic mirror (400 nm) and high-pass barrier filter (480 nm) before detection by an intensified charge-coupled device camera (IC-200, Photon Technology International). Video images were digitized and stored in the memory of a PTI M-50 imaging system. Images were analysed using Imagemaster and Felix software (Photon Technology International). [Ca2+]i was calculated using the formula of Grynkiewicz et al. [25]. Minimal and maximal fluorescence ratios were determined empirically as described in [24].

RESULTS

Differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells

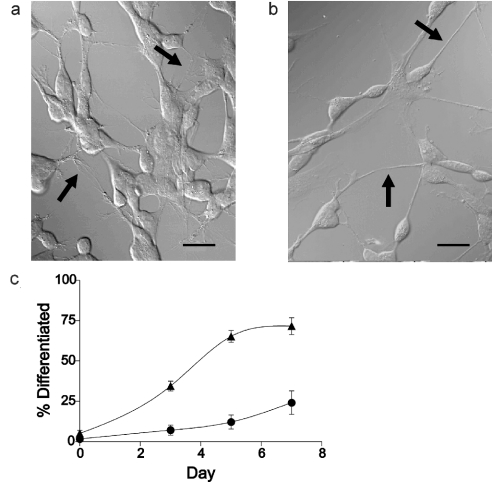

Control (‘undifferentiated’) cells, treated with ethanol, exhibited the same morphological appearance as before treatment; cell bodies were rounded or slightly elongated, with a mean diameter of 13.6±0.6 μm (n=16). They had short, stunted processes, often highly branched, emanating from the cell body (Figure 1a, arrows). After 7 days treatment with 1 μM 9cRA, cells appeared more neuronal, with more rounded cell bodies and long thin processes, or neurites, with fewer branches (Figure 1b, arrows) compared with the neurites of control (i.e. undifferentiated) cells. In addition, the growth rate of 9cRA-treated cells slowed in comparison with undifferentiated cells, with the doubling time increasing by approx. 50%.

Figure 1. 9cRA induces differentiation of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells.

Cells were treated with either 1 μM 9cRA or vehicle (ethanol) for 7 days. DIC micrographs of cells were taken after treatment. (a) Vehicle-treated cells, (b) 9cRA-treated cells and (c) graph showing percentage of differentiated cells after 0, 3, 5 and 7 days of vehicle (ethanol, ●) or 9cRA (▲) treatment. Cells were deemed differentiated if they exhibited neurites of length ≥50 μm. Values are given as means±S.E.M., n=5–8 fields of view. Pictures shown are representative of >50 experiments. Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Cells exhibiting one or more neurites ≥50 μm were deemed to be differentiated [19,20], and when such cells were expressed as a percentage of total cell number, these results confirmed that the extent of differentiation increased in a near linear manner with time for the first 5 days after 9cRA treatment (Figure 1c). This indicates that cells responded heterogeneously to 9cRA, i.e. some cells responded more quickly compared with others. A plateau was reached after 7 days treatment, with approx. 75% of cells differentiated. Hence not all of the cells in the population responded to 9cRA by undergoing differentiation. However, the proportion of cells deemed ‘differentiated’ may be a conservative reflection of the actual number since visualization of some extended neurites could have been obscured by other cells. After 7 days treatment, when cells were used for experiments, the number of differentiated cells in the 9cRA-treated population was significantly increased over that in the control population (P=0.0002).

Agonist-stimulated Ca2+ responses

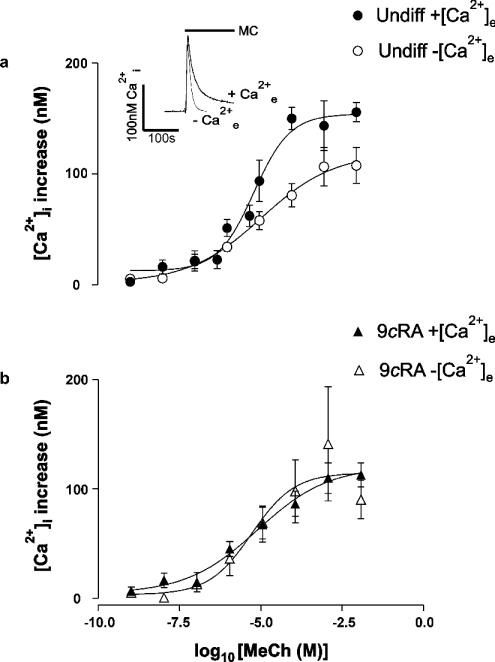

Application of MeCh (methacholine; 1 mM) or thapsigargin (200 nM) to a population of undifferentiated fura-2-loaded SH-SY5Y cells stimulated a classic ‘biphasic’ response; an initial rapid [Ca2+]i increase that was transient, the peak phase, was followed by a more prolonged [Ca2+]i signal, the plateau phase, that was acutely dependent on the presence of Ca2+e (extracellular Ca2+) (Figure 2a, inset shows typical responses to 1 mM MeCh). Undifferentiated cells were challenged with MeCh over the range 1–10 mM in the presence or absence of Ca2+e (Figure 2a). In both cases, the [Ca2+]i response was found to be saturable, with maximal increase in Ca2+ occurring between 1 and 10 mM MeCh. The EC50 values were similar under both conditions: 6.8 μM in the presence and 11.6 μM in the absence of Ca2+e. The amplitude of the initial [Ca2+]i rise evoked by MeCh in the absence of Ca2+e was decreased compared with the response in the presence of Ca2+e (Figure 2a, P=0.002 at 100 μM). The difference in amplitude was not due to depletion of the intracellular Ca2+ stores caused by the 180 s incubation in nominally Ca2+-free medium: assessment of store leakage using thapsigargin in our previously published method [24] revealed that the stores still contained 87±8% (n=3) of their Ca2+ after a 3 min incubation in this medium (A. M. Brown and T. R. Cheek, unpublished work).

Figure 2. Concentration-dependence of MeCh-stimulated [Ca2+]i increase – peak phase.

Fura-2-loaded populations of undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells were stimulated by the addition of MeCh. Graphs show the peak increase in [Ca2+]i above basal. (a) Undifferentiated vehicle (ethanol)-treated cells (Undiff) in the presence (●) or nominal absence (○) of Ca2+e. (b) 9cRA-differentiated cells in the presence (▲) or nominal absence (△) of Ca2+e. Data are means±S.E.M., n=3–8. Inset, typical biphasic [Ca2+]i response obtained by the addition of 1 mM MeCh (MeCh, shown by the solid bar) to cell populations of undifferentiated cells in the presence (+Ca2+e) and nominal absence of Ca2+e (−Ca2+e). Traces are representative of at least four experiments.

Experiments using 9cRA-differentiated cells gave results that mirrored those in undifferentiated cells: the maximal [Ca2+]i signal was observed between 1 and 10 mM MeCh and the EC50 values were similar: 7.1 μM in the presence and 4.7 μM in the absence of Ca2+e (Figure 2b). In contrast with undifferentiated cells, however, in 9cRA-differentiated cells there was no significant difference in the amplitude of the [Ca2+] rise evoked by MeCh, irrespective of whether Ca2+e was present (Figure 2b, P=0.68 at 100 μM). Direct comparison of the peak [Ca2+]i in undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells in the presence of Ca2+e reveals a significant difference in the peak [Ca2+]i increases observed in response to (particularly higher) concentrations of MeCh (e.g. P=0.003 at 100 μM). These findings suggest that Ca2+e may play little or no role in the peak phase of the Ca2+ response in 9cRA-differentiated cells, although it may contribute to the peak phase in undifferentiated cells.

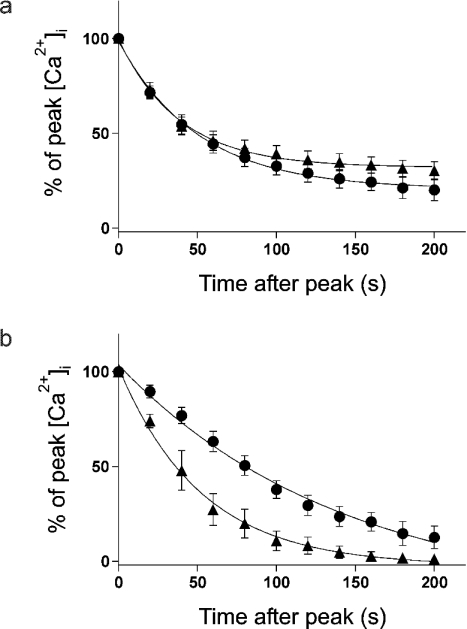

To investigate the plateau phase of the Ca2+ response, the time course of the decay from peak [Ca2+]i was determined (Figure 3). The data were normalized to allow direct comparison of decay rates, rather than the absolute concentration of Ca2+i. In response to a maximal concentration of MeCh, there was no significant difference in the rate constants for decay of the Ca2+ signal in undifferentiated versus 9cRA-differentiated cells (Figure 3a, rate constants=2.05±0.18×10−2 s−1 in undifferentiated and 2.62±0.27×10−2 s−1 in 9cRA-differentiated cells, P=0.12). Furthermore, in both cell types, the plateau phase is still apparent at 200 s (Figure 3a), implying that Ca2+ entry may still be occurring at this time. To investigate whether classical CCE could be involved in maintaining this plateau phase, similar time courses were determined using a maximal concentration of thapsigargin (Figure 3b). In the present study, the rate constant for decay of the Ca2+ signal in 9cRA-differentiated cells was significantly greater than that in undifferentiated cells (Figure 3b, rate constants=0.72±0.13×10−2 s−1 in undifferentiated and 2.01±0.47×10−2 s−1 in 9cRA-differentiated cells, P=0.02). Furthermore, in 9cRA-differentiated cells the plateau phase appears to have terminated by approx. 160 s, whereas it is still present in undifferentiated cells at this time. These results indicated that Ca2+ entry occurs during the plateau phase of the MeCh-induced responses in both cell types. This entry could involve CCE in undifferentiated cells, but in 9cRA-differentiated cells CCE may be occurring to a much lesser extent, if at all, as evidenced by the rapid decay and transient nature of the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ signal.

Figure 3. Decay in [Ca2+]i after peak response to thapsigargin or MeCh stimulation – plateau phase.

Fura-2-loaded populations of undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells were stimulated by the addition of 1 mM MeCh or 200 nM thapsigargin in the presence of Ca2+e. Graphs show the normalized increase in [Ca2+]i above basal at times after reaching the peak of the response (0 s) as a percentage of the peak [Ca2+]i increase. (a) Undifferentiated (●) and 9cRA-differentiated (▲) cells stimulated with 1 mM MeCh. (b) Undifferentiated (●) and 9cRA-differentiated (▲) cells stimulated with 200 nM thapsigargin. Data are means±S.E.M., n=5–7. Best-fit curves were plotted using one-phase exponential decay equations.

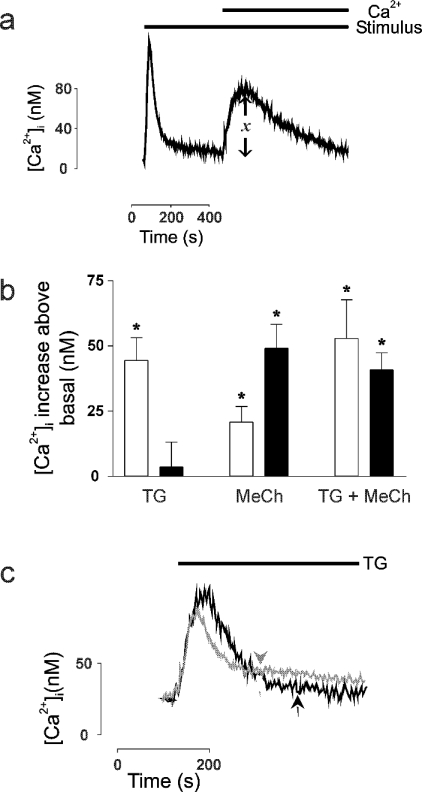

A ‘Ca2+-addback’ technique was then used to determine the absolute rise in [Ca2+]i that was attributable solely to Ca2+ entry and which constitutes the plateau phase of the response (‘x’, Figure 4a). Thapsigargin stimulated significant Ca2+ entry above the basal level in undifferentiated cells (P=0.004) but not in 9cRA-differentiated cells (P=0.73) (Figure 4b). This was not due to insufficient emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores by thapsigargin: a significant increase in [Ca2+]i was seen in both undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells when stimulated by thapsigargin in the absence of Ca2+e and in each cell type the magnitude of the response was comparable (Figure 4c; 65.8±8.1 nM, n=4 in undifferentiated and 75.0±5.8 nM, n=3 in 9cRA-differentiated cells, P=0.43). Furthermore, the time course of the response was similar. A subsequent addition of MeCh did not stimulate any further Ca2+i release suggesting that thapsigargin does empty stores fully in both cell types (Figure 4c). These results confirmed that CCE occurs in undifferentiated cells but that it appears to be down-regulated or shut off in 9cRA-differentiated cells. In response to MeCh, there was a significant increase in Ca2+ entry above the basal level in both cell types (P=0.02 in undifferentiated cells; P=0.003 in 9cRA-differentiated cells), although there was significantly less entry in undifferentiated cells compared with their 9cRA-differentiated counterparts (P=0.03). Since CCE appears to be absent from 9cRA-differentiated cells, this provided direct evidence that the pathway(s) of Ca2+ entry in response to hormone differ in each cell type. When both stimuli were added simultaneously there was no significant additivity in Ca2+ entry above that stimulated by MeCh alone (although in undifferentiated cells the difference was close to significance: P=0.09, Figure 4b). These results using MeCh indicated, first, that MeCh activates an alternative, NCCE Ca2+ entry pathway in 9cRA-differentiated cells and, secondly, that MeCh stimulates predominantly CCE in undifferentiated cells (since there was no significant additivity due to thapsigargin).

Figure 4. Thapsigargin and MeCh stimulate Ca2+ entry in undifferentiated cells, whereas only MeCh stimulates entry in 9cRA-differentiated cells.

Fura-2-loaded undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cell populations were stimulated in the nominal absence of Ca2+e and the initial peak of the response was allowed to proceed to completion before Ca2+e was added back to the system to permit the second plateau or entry phase to occur. The magnitude of this second response was then determined. (a) Typical trace showing the changes in [Ca2+]i which occurred over time during a ‘Ca2+ add back’ experiment. Solid bars indicate the presence of stimulus and Ca2+e. ‘x’ indicates the region of the response measured. The trace is representative of at least four experiments. (b) [Ca2+]i increases above basal level occurring on Ca2+ add back in response to stimulation with 200 nM thapsigargin (TG), 1 mM MeCh (MeCh) or both (TG+MeCh) in undifferentiated (□) and 9cRA-differentiated (■) cells. Data are means±S.E.M., n=4–7. * indicates significant deviation from zero (P<0.05). (c) Typical traces showing changes in [Ca2+]i when undifferentiated (grey) and 9cRA-differentiated (black) cells were stimulated with 200 nM thapsigargin and 1 mM MeCh sequentially in the nominal absence of Ca2+e. Solid bar indicates the presence of thapsigargin (TG), arrowheads indicate time of addition of MeCh. Traces are representative of at least three experiments.

SH-SY5Y cells express both verapamil-sensitive and ω-conotoxin GVIA-sensitive VOCs (voltage-operated Ca2+ channels) [13–15] and muscarinic agonists are reported to depolarize these cells [26]. Changes in [Ca2+]i in single cells were therefore monitored in the presence and absence of the VOCI (voltage-operated Ca2+ channel inhibitors) verapamil (10 μM; L-type specific) and ω-conotoxin GVIA (1 μM; N-type specific). A relatively small but significant inhibition of the MeCh-stimulated increase in peak [Ca2+]i was detected in undifferentiated cells (14.8±3.6%, n=84, P=0.0001), although there was still a significant increase in [Ca2+]i. There was no significant inhibition of the peak [Ca2+]i increase in 9cRA-differentiated cells (5.77±4.2%, n=50, P=0.18). These results are consistent with our earlier observations of significant Ca2+ entry occurring during the peak phase in undifferentiated but not 9cRA-differentiated cell populations (Figure 2). During the plateau phase, we observed a significant inhibition of the MeCh-induced [Ca2+]i increase in both cell types (45.75±4.0%, n=84, P<0.0001 for undifferentiated and 21.37±4.9%, n=50, P<0.0001 for 9cRA-differentiated cells). This was also in agreement with our earlier results showing Ca2+ entry during the plateau phase in both undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated populations of cells (Figure 3). Again, significant increases in [Ca2+]i occurred even when the inhibitors were present, although the extent of inhibition was much greater in undifferentiated than in 9cRA-differentiated cells (P=0.0002). To confirm that the VOCI were fully functional under the conditions used, single undifferentiated cells were stimulated with K+, in the presence and absence of the VOCI. Cells responded with an increase in [Ca2+]i, which was abolished in the presence of VOCI. This inhibitory effect was reversible (F. C. Riddoch, A. M. Brown and T. R. Cheek, unpublished work; but see [27]). These results indicate that VOCs make a significant contribution to the Ca2+ entry observed in response to MeCh stimulation, more so in undifferentiated than in 9cRA-differentiated cells. However, it is apparent that other, alternative pathways are functioning alongside VOCs in the response to MeCh in both cell types.

Agonist-stimulated Mn2+ entry

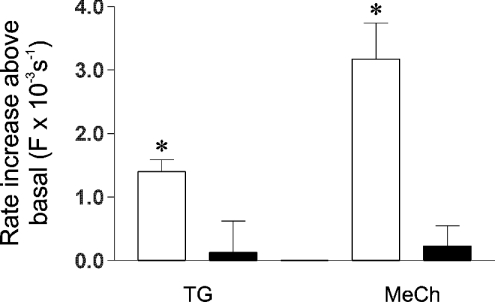

The Mn2+ quench technique was next employed [24] to provide a direct measure of divalent cation entry. The rate constants for the quench of fura-2 in resting cells were similar in undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells (A. M. Brown and T. R. Cheek, unpublished work). Thapsigargin stimulated a significant increase in the rate of quench above the basal level in undifferentiated cells (P=0.002, Figure 5), indicating that CCE is operative under these conditions and that the pathway is Mn2+-permeable. However, thapsigargin had no effect on the rate of quench in 9cRA-differentiated cells (P=0.80, Figure 5), suggesting that, in agreement with the previous results (Figure 4b), the hormone-sensitive CCE pathway may be down-regulated or shut-off. On stimulation with MeCh, a significant increase in rate constant for the quench of fura-2 was observed in undifferentiated cells (P=0.0002, Figure 5). This directly demonstrates that there is a MeCh-stimulated divalent cation entry pathway in these cells, in agreement with previous findings (Figures 3 and 4). However, in 9cRA-differentiated cells, there was no significant increase in the rate constant for fura-2 quench on MeCh stimulation (P=0.48, Figures 5). Since this technique should detect all divalent cation entry, irrespective of whether it occurs during the peak and/or plateau phase, this latter finding is consistent with the notion that Ca2+ entry plays little or no role in the peak response to MeCh in differentiated cells (Figure 2), but is at odds with the notion that Ca2+ entry is occurring during the plateau phase in these cells (Figures 3 and 4). However, since these results were reminiscent of the results obtained using thapsigargin (Figure 4b), it seems possible that this also reflects the down-regulation or loss of CCE in these cells. It may also suggest that the Ca2+ entry pathway stimulated by MeCh in 9cRA-differentiated cells is Mn2+-impermeable.

Figure 5. Thapsigargin and MeCh stimulate divalent cation entry in undifferentiated but not 9cRA-differentiated cells.

Fura-2-loaded undifferentiated (□) and 9cRA-differentiated (■) cells were stimulated in Krebs buffer containing 100 μM MnCl2 and the subsequent Mn2+ quench of fura-2 fluorescence was monitored at 360 nm excitation. Control cells were incubated in the presence of Mn2+ only. Cells were stimulated using 200 nM thapsigargin (TG) or 1 mM MeCh (MeCh). Bars show the average stimulated increase in rate of Mn2+ quench above the rate obtained from control cells. Rates are shown as first-order rate constants for the quench of fura-2, obtained by fitting single-exponential decay curves to quench traces, such as those illustrated in Figure 6. Data are means±S.E.M., n=5–17. * indicates significant deviation from zero (P=0.002 in thapsigargin-stimulated undifferentiated cells, and P=0.0002 in MeCh-stimulated undifferentiated cells).

When these experiments were repeated in the presence of VOCI, there was no discernible inhibition of basal rates of Mn2+ quench. Neither was there any inhibition of thapsigargin or MeCh-stimulated Mn2+ quench rates in undifferentiated cells (rate increase=2.2±0.5×10−3 s−1, n=3, P=0.13 in thapsigargin-stimulated and 2.6±0.7×10−3 s−1, n=8, P=0.55 in MeCh-stimulated cells). Since an inhibitory effect of VOCI was detected when MeCh-stimulated Ca2+ changes were measured directly (see above), this would suggest that the MeCh-stimulated VOCs are Mn2+-impermeable.

CCE is not the only divalent cation entry pathway

Two lines of experimental evidence raised the possibility that MeCh may stimulate one or more Ca2+ entry pathway(s) in addition to CCE and VOCs in these cells. First, in undifferentiated cells the MeCh-stimulated rate of Mn2+ quench is noticeably higher compared with that stimulated by thapsigargin, and was extremely close to significance (P=0.07, Figure 5). This entry was unlikely to be due to VOCs since these appear to be Mn2+-impermeable (see above). Secondly, in MeCh-stimulated 9cRA-differentiated cells there is a plateau phase of Ca2+ entry (Figures 3a and 4b), which is only partially inhibited by VOCI (see above) yet CCE is not detected (Figures 3b, 4b and 5). To test this hypothesis, rate constants of Mn2+ quench were measured in undifferentiated cells after sequential addition of thapsigargin and then MeCh. In separate experiments this order of addition was reversed. When MeCh was added subsequent to thapsigargin, the rate of Mn2+ quench was significantly increased above that stimulated by thapsigargin (P=0.02, Figure 6a and inset). When thapsigargin was added subsequent to MeCh, however, there was no increase in the rate of quench above that stimulated by MeCh (P=0.81, Figure 6b and inset). In addition, the absolute rates of Mn2+ quench stimulated by MeCh were not significantly different, regardless of whether MeCh was the first or second addition (P=0.42, Figure 6). Since addition of MeCh subsequent to thapsigargin does not stimulate further Ca2+i release (Figure 4c), these results indicated that in undifferentiated cells, MeCh stimulates (at least) one divalent cation entry pathway in addition to classical CCE. Similar experiments were also performed on 9cRA-differentiated cells, but, in agreement with earlier findings (Figure 5), no significant Mn2+ quench was detected (A. M. Brown and T. R. Cheek, unpublished work).

DISCUSSION

The neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y shows morphological and biochemical properties of cells derived, as sympathetic neurons, from the neural crest. Morphological differentiation towards mature ganglion-like cells occurs when SH-SY5Y cells are cultured in the presence of all-trans RA [14,17–20,28]. However, it has been reported that 9cRA is the more efficacious biologically active isomer in terms of modulating differentiation, proliferation and gene expression, owing to its different biological properties and distinct mechanisms of action [29]. Hence 9cRA may induce biochemical changes in SH-SY5Y cells that are not induced by the all-trans isomer. Thus in contrast with existing studies, in the present study we have differentiated cells using 9cRA. Morphological differentiation towards mature ganglion-like cells became evident when SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in the presence of 1 μM 9cRA (Figure 1) [30]. Similar observations in these cells have been reported in response to all-trans RA [19], although higher concentrations of the drug are typically used (e.g. 10 μM, [18,20,28]).

Concentration–response curves for peak [Ca2+]i stimulated by MeCh in the presence and absence of Ca2+e suggested that Ca2+ entry may contribute to the peak Ca2+ response in undifferentiated but not 9cRA-differentiated cells (Figure 2). Also, a hormone-stimulated Mn2+ entry pathway was present in undifferentiated but not 9cRA-differentiated cells (Figure 5). It is probable that the pathway that is absent in 9cRA-differentiated cells is predominantly classical CCE, since thapsigargin stimulated Ca2+ (Figure 4b) and Mn2+ (Figure 5) entry in undifferentiated cells (see also [16]) but not in 9cRA-differentiated cells. However, we considered the possibility that the CCE pathway may have altered its Ca2+- and Mn2+-selectivity on differentiation: differentiation of BC3H1 (smooth muscle) cells resulted in an approx. 2-fold decrease in CCE and a concomitant 2-fold increase in capacitative Mn2+ entry [31]. The reverse may have occurred in differentiating SH-SY5Y cells. Although we cannot exclude some decrease in Mn2+ permeability, a change in selectivity is unlikely because the decrease in capacitative Mn2+ entry (Figure 5) was mirrored by a decrease in CCE (Figure 4b). Thus the most probable explanation is that a Ca2+- and Mn2+-permeable CCE pathway has become either shut-off or down-regulated in 9cRA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells.

The apparent absence or down-regulation of a classical CCE pathway in 9cRA-differentiated cells was unexpected, given that such a pathway is well established in undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells [16,18,32]. No difference in peak Ca2+ response stimulated by MeCh between undifferentiated and differentiated cells was observed in a previous study by Martin et al. [18], but the all-trans RA isomer was used, making precise comparison with the present study problematic (see above). However, their conclusion that mechanisms other than the measured increase in InsP3 regulate the elevation in [Ca2+]i is supported by the present study, which shows regulation at the level of Ca2+ entry [18].

Decreased CCE has been reported during chick retinal development [33] and in differentiating NG108-15× glioma cells [34]. In these studies, the decrease in CCE appeared to correlate with a significant decrease in the size of the thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ store, as judged by the amplitude of the peak phase of the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ signal. In the present study, however, the thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ store remains fully intact (Figure 4c). Similarly, in differentiating embryonic (E) rat cortical neurons, the thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ stores remained intact but a Ca2+- and Mn2+-permeable entry component was lost. Whether this entry component represented classical CCE was not directly investigated, although it was found to be voltage-independent [35]. The key point connecting all of these studies is the suggestion that CCE occurs more intensely in undifferentiated (i.e. proliferating) cells compared with differentiated cells. The precise relationship between CCE and differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells was not analysed in the present study, but it is noteworthy that SH-SY5Y cells treated with RA in low Ca2+e were found not to differentiate [28]. It has also been suggested that TRP (transient receptor potential) protein-mediated CCE is required for differentiation to occur [36]. The present results raise the possibility that down-regulation of CCE is then required for maintenance of the differentiated state.

The mechanism(s) underlying the down-regulation of CCE is not clear. One possibility is that expression of the putative channel protein(s) involved may be down-regulated. There is a report of an increase in thapsigargin-stimulated Ca2+ influx accompanied by up-regulation of three TRP isoforms after differentiation of human stem cells to platelets [37]. Therefore our observation of an apparent absence of CCE may reflect either the down-regulation (or indeed absence) of particular TRP isoforms in 9cRA-differentiated cells, which are present in their undifferentiated counterparts. Alternatively, the CCE pathway may still be present and functioning in differentiated cells, albeit at a decreased level, but with substantial alterations in its spatial and/or temporal characteristics such that the signal may only be detected using high-resolution imaging techniques [3]. A third possible mechanism of down-regulation of CCE may be an as yet unidentified form of active repression by the putative NCCE pathway [10–12,21] (see below).

Despite the absence of CCE in 9cRA-differentiated cells, there is nevertheless a significant hormone-induced Ca2+ entry component that constitutes a plateau phase of the Ca2+ signal (Figures 3a and 4b). One obvious candidate for this putative additional Ca2+ entry pathway is a VOC, since SH-SY5Y cells have both L- and N-type VOCs [13–15]. In addition, voltage-dependent Ca2+ current density has been reported to increase after RA-induced differentiation [14], perhaps as a result of increased channel expression [15]. Our observation of a K+-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in both undifferentiated and 9cRA-differentiated cells [27] supports the existence of VOCs in these cells. However, they form only a relatively minor part of the response to stimulation by MeCh (see results). Previous studies using SH-SY5Y cells have concluded that VOCs played no part in muscarinic-stimulated Ca2+ entry since no effect of VOCI was observed [13,16]. However, while these studies also employed the N-type inhibitor ω-conotoxin GVIA, in one case it was used at a 10-fold lower concentration, and alternative muscarinic agonists and L-type inhibitors to those used in the present study were employed [13,16].

Furthermore, although the MeCh-stimulated VOCs were found to be Mn2+ impermeable (see results), we have shown, in undifferentiated cells, that MeCh is able to stimulate Mn2+ entry in addition to CCE (Figure 6). This voltage-independent additional pathway may constitute a diacylglycerol-activated, non-store-dependent Ca2+ entry pathway, similar to those described recently [8], and postulated to involve members of the TRP protein family [38]. However, a more probable possibility is that the additional pathways represent a form of the arachidonic acid-activated Ca2+ entry pathway ‘NCCE’ [39] or ‘IARC’ (arachidonate-regulated calcium current [9]) [10,12]. NCCE/IARC and CCE are reported to operate in a mutually antagonistic reciprocal manner, such that in the absence of CCE, NCCE/IARC is the predominant pathway for Ca2+ entry [10–12,21]. Thus in undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells responding to maximum hormone concentration, CCE would be expected to predominate (Figures 4b and 5). NCCE/IARC may also be present but plays a minor role (Figure 6a), perhaps because it is actively attenuated by CCE [10,21]. A low level of activation of NCCE/IARC would be consistent with a previous observation in these cells that a voltage-independent Ca2+ entry pathway occurred alongside CCE, yet contributed little to muscarinic-induced entry [16]. In 9cRA-differentiated cells, however, CCE is absent or down-regulated. The NCCE/IARC component may then predominate and is detected as a measurable [Ca2+]i increase after Ca2+ add back which is not augmented by thapsigargin (Figure 4b). Although the molecular identity of IARC remains to be elucidated, this channel may also be a TRP protein [40].

We have demonstrated a functionally significant alteration in the mechanism of hormone-stimulated Ca2+ entry on 9cRA-induced differentiation of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. In undifferentiated cells, in addition to voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry, two voltage-independent Ca2+ entry pathways appear to operate in response to a maximal hormone stimulation, the predominant one of which appears to be CCE. These entry pathways contribute to both the peak and plateau phases of the hormone-induced Ca2+ signal. After differentiation CCE is undetectable, but both a voltage-dependent and a voltage-independent Ca2+ entry pathway that contribute to only the plateau phase of the response remain. The identity of this latter ‘NCCE’ pathway and whether its activity becomes up-regulated in the absence of CCE [11,12,21] are currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Crumiere, U. Strunck and P. McParlin for technical assistance and A. D. J. Pearson for advice and support. This work was supported by a project grant from the NECCRF and a programme grant from the MRC to T. R. C. F. C. R. was supported by a BBSRC studentship.

References

- 1.Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Lipp P. Calcium – a life and death signal. Nature (London) 1998;395:645–648. doi: 10.1038/27094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge M. J. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 1997;499:291–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bootman M. D., Lipp P., Berridge M. J. The organisation and functions of local Ca2+ signals. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2213–2222. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Putney J. W., Jr Capacitative calcium entry revisited. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:611–624. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90016-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor C. W. Controlling calcium entry. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2002;111:767–769. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putney J. W., Jr, Broad L. M., Braun F. J., Lievremont J. P., Bird G. S. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2223–2229. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barritt G. J. Receptor-activated Ca2+ inflow in animal cells: a variety of pathways tailored to meet different intracellular Ca2+ signalling requirements. Biochem. J. 1999;337:153–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tesfai Y., Brereton H. M., Barritt G. J. A diacylglycerol-activated Ca2+ channel in PC12 cells (an adrenal chromaffin cell line) correlates with expression of the TRP-6 (transient receptor potential) protein. Biochem. J. 2001;358:717–726. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mignen O., Shuttleworth T. J. IARC, a novel arachidonate-regulated, noncapacitative Ca2+ entry channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9114–9119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo D., Broad L. M., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr Mutual antagonism of calcium entry by capacitative and arachidonic acid-mediated calcium entry pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20186–20189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moneer Z., Taylor C. W. Reciprocal regulation of capacitative and non-capacitative Ca2+ entry in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells: only the latter operates during receptor activation. Biochem. J. 2002;362:13–21. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peppiatt C. M., Holmes A. M., Seo J. T., Bootman M. D., Collins T. J., McDonald F., Roderick H. L. Calmidazolium and arachidonate activate a calcium entry pathway that is distinct from store-operated calcium influx in HeLa cells. Biochem. J. 2004;381:929–939. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert D. G., Whitham E. M., Baird J. G., Nahorski S. R. Different mechanisms of Ca2+ entry induced by depolarization and muscarinic receptor stimulation in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1990;8:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90026-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toselli M., Masetto S., Rossi P., Taglietti V. Characterization of a voltage-dependent calcium current in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y during differentiation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1991;3:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passafaro M., Clementi F., Sher E. Metabolism of ω-conotoxin-sensitive voltage-operated calcium channels in human neuroblastoma cells: modulation by cell differentiation and anti-channel antibodies. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:3372–3379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03372.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grudt T. J., Usowicz M. M., Henderson G. Ca2+ entry following store depletion in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;36:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00248-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackrill J. J., Challiss R. A. J., O'Connell D. A., Lai F. A., Nahorski S. R. Differential expression and regulation of ryanodine receptor and myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels in mammalian tissues and cell lines. Biochem. J. 1997;327:251–258. doi: 10.1042/bj3270251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin A. K., Nahorski S. R., Willars G. B. Complex relationship between Ins(1,4,5)P3 accumulation and Ca2+-signalling in a human neuroblastoma revealed by cellular differentiation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:1559–1566. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Påhlman S., Ruusala A. I., Abrahamsson L., Mattsson M. E., Esscher T. Retinoic acid-induced differentiation of cultured human neuroblastoma cells: a comparison with phorbolester-induced differentiation. Cell Differ. 1984;14:135–144. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(84)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolini G., Miloso M., Zoia C., Di Silvestro A., Cavaletti G., Tredici G. Retinoic acid differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells: an in vitro model to assess drug neurotoxicity. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2477–2481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mignen O., Thompson J. L., Shuttleworth T. J. Reciprocal regulation of capacitative and arachidonate-regulated noncapacitative Ca2+ entry pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:35676–35683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown A. M., Riddoch F. C., Redfern C. P. F., Cheek T. R. Changes in Ca2+ entry mechanisms following retinoic acid-induced differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2002;544P:6P. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown A. M., Riddoch F. C., Robson A., Redfern C. P. F., Cheek T. R. Retinoic acid-induced differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells results in alterations in Ca2+ entry characteristics. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2004;557P:PC88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett D. L., Bootman M. D., Berridge M. J., Cheek T. R. Ca2+ entry into PC12 cells initiated by ryanodine receptors or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Biochem. J. 1998;329:349–357. doi: 10.1042/bj3290349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Åkerman K. E. Depolarization of human neuroblastoma cells as a result of muscarinic receptor-induced rise in cytosolic Ca2+ FEBS Lett. 1989;242:337–340. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80497-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riddoch F. C., Cheek T. R. Changes in Ca2+ signalling accompany retinoic acid-induced differentiation of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 2004;557P:PC89. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Celli A., Treves C., Nassi P., Stio M. Role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and extracellular calcium in the regulation of proliferation in cultured SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Neurochem. Res. 1999;24:691–698. doi: 10.1023/a:1021060610958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovat P. E., Irving H., Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M., Bernassola F., Malcolm A. J., Pearson A. D. J., Melino G., Redfern C. P. F. Retinoids in neuroblastoma therapy: distinct biological properties of 9-cis- and all-trans-retinoic acid. Eur. J. Cancer. 1997;33:2075–2080. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovat P. E., Lowis S. P., Pearson A. D. J., Malcolm A. J., Redfern C. P. F. Concentration-dependent effects of 9-cis retinoic acid on neuroblastoma differentiation and proliferation in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;182:29–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broad L. M., Powis D. A., Taylor C. W. Differentiation of BC3H1 smooth muscle cells changes the bivalent cation selectivity of the capacitative Ca2+ entry pathway. Biochem. J. 1996;316:759–764. doi: 10.1042/bj3160759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert D. G., Nahorski S. R. Muscarinic-receptor-mediated changes in intracellular Ca2+ and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate mass in a human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y. Biochem. J. 1990;265:555–562. doi: 10.1042/bj2650555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaki Y., Sugioka M., Fukuda Y., Yamashita M. Capacitative Ca2+ influx in the neural retina of chick embryo. J. Neurobiol. 1997;32:62–68. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199701)32:1<62::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ichikawa J., Fukuda Y., Yamashita M. In vitro changes in capacitative Ca2+ entry in neuroblastoma X glioma NG108-15 cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;246:120–122. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maric D., Maric I., Barker J. L. Developmental changes in cell calcium homeostasis during neurogenesis of the embryonic rat cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2000;10:561–573. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X., Zagranichnaya T. K., Gurda G. T., Eves E. M., Villereal M. L. A TRPC1/TRPC3-mediated increase in store-operated calcium entry is required for differentiation of H19-7 Hippocampal neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43392–43402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Dekker E., Molin D. G., Breikers G., van Oerle R., Akkerman J. W., van Eys G. J., Heemskerk J. W. Expression of transient receptor potential mRNA isoforms and Ca2+ influx in differentiating human stem cells and platelets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1539:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma H. T., Patterson R. L., van Rossum D. B., Birnbaumer L., Mikoshiba K., Gill D. L. Requirement of the inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Science. 2000;287:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broad L. M., Cannon T. R., Taylor C. W. A non-capacitative pathway activated by arachidonic acid is the major Ca2+ entry mechanism in rat A7r5 smooth muscle cells stimulated with low concentrations of vasopressin. J. Physiol. (Cambridge, U.K.) 1999;517:121–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0121z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X., Babnigg G., Zagranichnaya T., Villereal M. L. The role of endogenous human Trp4 in regulating carbachol-induced calcium oscillations in HEK-293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13597–13608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]