Abstract

Endometrial decidualization resistance (DR) is implicated in various gynecological and obstetric conditions. Here, using a multi-omic strategy, we unraveled the cellular and molecular characteristics of DR in patients who have suffered severe preeclampsia (sPE). Morphological analysis unveiled significant glandular anatomical abnormalities, confirmed histologically and quantified by the digitization of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of endometrial samples from patients with sPE (n = 11) and controls (n = 12) revealed sPE-associated shifts in cell composition, manifesting as a stromal mosaic state characterized by proliferative stromal cells (MMP11 and SFRP4) alongside IGFBP1+ decidualized cells, with concurrent epithelial mosaicism and a dearth of epithelial–stromal transition associated with decidualization. Cell–cell communication network mapping underscored aberrant crosstalk among specific cell types, implicating crucial pathways such as endoglin, WNT and SPP1. Spatial transcriptomics in a replication cohort validated DR-associated features. Laser capture microdissection/mass spectrometry in a second replication cohort corroborated several scRNA-seq findings, notably the absence of stromal to epithelial transition at a pathway level, indicating a disrupted response to steroid hormones, particularly estrogens. These insights shed light on potential molecular mechanisms underpinning DR pathogenesis in the context of sPE.

Subject terms: Reproductive disorders, Proteomics, Transcriptomics

A multi-omics analysis of decidualization resistance, which is implicated in various gynecological and obstetric conditions, in patients with a history of severe preeclampsia revealed defects in the stroma, epithelium and epithelial-to-stromal transition, with findings validated in a separate replication cohort.

Main

Pregnancy health is shaped during the periconceptional period due to the interplay between the implanting embryo and the maternal endometrium1. Decidualization entails the functional and morphological changes that occur within the endometrium, transforming the maternal uterine lining to accommodate the invasive trophoblast2–4. The endometrial stromal cell transformation is hormonally regulated, driven by increasing progesterone levels and local cAMP production5,6, which stimulate the synthesis of a complex network of intracellular and secreted proteins7. It starts in the early secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, independent of the presence of a conceptus, in areas adjacent to the uterine spiral arteries, thereafter spreading throughout the endometrium8.

Decidualization resistance (DR) refers to the inability of the endometrium to undergo these specific changes and has been documented in reproductive disorders, including endometriosis9–11, miscarriage12, recurrent pregnancy loss13,14 and great obstetrical syndromes. The latter include preeclampsia (PE)15–17, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)18 and/or placenta accreta spectrum disorder19.

PE is a major obstetric complication affecting 8% of first-time pregnancies. It is characterized by the new onset of hypertension, proteinuria and other signs such as vascular endothelial damage20. The life-threatening condition known as severe PE (sPE) is diagnosed based on higher blood pressure criteria (systolic ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic ≤ 100 mm Hg), symptoms of central nervous system dysfunction, hepatic abnormalities, thrombocytopenia, renal abnormalities and/or pulmonary edema21. The most accepted biological origin is that sPE is a placental insufficiency syndrome mediated by early shallow cytotrophoblast invasion of uterine decidua and spiral arterioles, leading to incomplete endovascular invasion and altered uteroplacental perfusion20,22,23. We provided evidence of a decidualization defect in women with sPE, detected at the time of delivery and persisting years after the affected pregnancy15. Endometrial bulk RNA-seq results from affected women post-sPE revealed altered ovarian hormone receptor signaling pathways16.

Here we initially observed gross and microscopic endometrial glandular defects in late secretory endometrium from former patients with sPE. Then, we assemble a spatially resolved single-cell multi-omic characterization of the DR using sPE as a clinical model. Our objective is to gain insights into this pathological condition, combining different omics techniques including single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), spatial transcriptomics and laser capture microdissection-coupled mass spectrometry (LCM–MS) with different sample sets (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, we provide a detailed description of the whole status of cells, cell communications, perturbations in specific cell communication pathways at scRNA-seq and spatial and proteomic resolution.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Experimental design and workflow of each technology.

Experimental design and workflow for processing endometrial biopsies from sPE and control samples of morphological analysis, single-cell RNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics and spatial proteomics.

Results

Gross, microscopic and single-cell changes in sPE

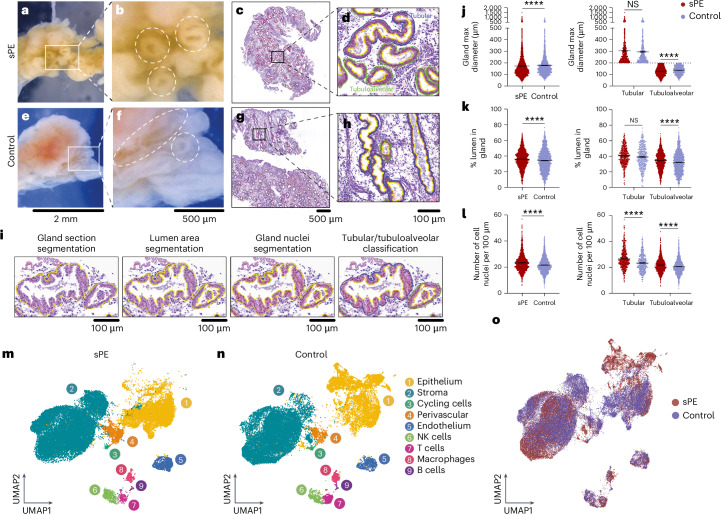

Macroscopical visualization of endometrial tissue revealed that the openings of the glands were dilated in the patients (Fig. 1a,b) compared to the control group (Fig. 1e,f). Scanning and digitization of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections from former patients with sPE (Fig. 1c,d) and controls (Fig. 1g,h) confirmed this finding (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). We developed a pipeline of analysis to segment gland sections (Fig. 1i). Specifically, data showed that the dilation was observed mainly in tubuloalveolar gland sections with smaller area, diameter and increased circularity (Fig. 1j and Extended Data Fig. 2a,c). Moreover, patients with sPE have a higher percentage of lumen area with more irregularities (less solidity; Fig. 1k and Extended Data Fig. 2b), and a higher number of cells in gland epithelium (more serrated; Fig. 1l) were observed in both tubular and tubuloalveolar gland sections compared to controls. We took these findings as preliminary evidence of DR endometrial defects during the late secretory phase of the cycle among former patients with sPE.

Fig. 1. Morphological features in DR reflected in single-cell atlas in sPE and control conditions.

a, Representative image of one endometrial tissue collected during the late secretory phase from a woman with a previous sPE. b, Zoom-in of the macroscopical glands of the endometrial tissue of a. Dashed circles highlight the glands. c, Representative H&E slides staining endometrial tissue of an sPE sample (n = 11). d, Zoom-in of endometrial tissue of an sPE sample and gland classification (n = 11). e, Representative image of one endometrial tissue collected during the late secretory phase from a control woman. f, Zoom-in of the macroscopical glands of the endometrial tissue of e. Dashed circle and dashed ellipsis highlight the glands. g, Representative H&E slides staining of cross-section endometrial tissue of a control sample (n = 9). h, Zoom-in of the representative H&E slides staining of longitudinal-section endometrial tissue of a control sample (n = 9). i, Segmentation and classification of tubular and tubuloalveolar glands for subsequent analysis. j, Violin plots representing maximum glandular diameter in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. k, Violin plots representing the percentage of the lumen in glands in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. l, Violin plots representing the number of cell nuclei in 100 µm in glands in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. Two-sided Wilcoxon test (****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant). m, UMAP of single-cell integration of sPE cells (28,154) of the major cell types of the endometrium during the late secretory phase (n = 11). n, UMAP of single-cell integration of control cells (37,227) of the major cell types of the endometrium during the late secretory phase (n = 12). o, UMAP of the 65,381 high-quality cells of types of merged cells of both sPE and control samples.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Additional morphological parameters.

(a) Violin plots representing gland area (µm2) in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test (**p = 0.0013), (****p < 0.0001). (b) Violin plots representing lumen solidity (0–1) in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test (**p = 0.0027), (***p < 0.001). (c) Violin plots representing gland circularity (0–1) in sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) samples and detailed tubular and tubuloalveolar glandular classification. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test (***p < 0.001). (d) Representative H&E slides staining endometrial tissue of an sPE sample (sPE patient 1). (e) Representative H&E slides staining endometrial tissue of an sPE sample (sPE patient 2). (f) Representative H&E slides staining endometrial tissue of a control sample (control 1). (g) Representative H&E slides staining endometrial tissue of a control sample (control 2).

We used a scRNA-seq approach to uncover molecular correlates underlying the observed morphological differences. Altogether, we profiled 65,381 cells (Supplementary Table 3), integrated the transcriptomes and projected them in a uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of sPE and control groups (Fig. 1m,n). The following nine major cell types were identified: epithelium, stroma, cycling stroma, perivascular, endothelium, natural killer (NK) cells, T cells, macrophages and B cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 4). Global integration of the merged patients and control datasets enabled an initial comparison of the cellular composition of the endometrial biopsies from the two groups (Fig. 1o).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Expression of canonical markers in each identified cell type.

(a) Dot plot of the top canonical markers of the nine major cell populations identified. (b) Dot plot of the top canonical markers of the stromal cell subtypes. (c) Dot plot of the top canonical markers of the epithelial cell subtypes. (d) Dot plot of the top canonical markers of the cell types involved in the epithelial-to-stroma transition. Average log2(FC) is represented by the color scale; dot size represents the percentage of cells expressing that gene.

Differential expression analysis revealed that C2CD4B is upregulated in endothelial cells in sPE, which is associated with acute inflammation24. Immune cells, including macrophages, NK cells and B cells, showed inflammatory dysregulation with higher expression of interleukin-1-beta (IL-1B), CCL5 (ref. 25) and SCGB1D2 (ref. 26). Upregulation of IL-1B and TNF in macrophages contributed to endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular resistance, while increased IL32 in NK cells promoted neutrophil activation and sPE development27 (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b).

Extended Data Fig. 4. DEGs associated with DR in affected cell subpopulations.

(a) Dot plot representing DEGs (adjusted log10(p val)) of immune cells (macrophages, natural killers and B cells). (b) Dot plot representing DEGs (adjusted log10(p val)) of endothelium. (c) Dot plot representing DEGs (adjusted log10(p val)) of decidualized stroma 1, 2 and 3, stromal transition and proliferative stroma subpopulations. Average log2(FC) is represented by the color scale; dot size represents the percentage of cells expressing that gene. (d) Dot plot representing DEGs (adjusted log10(p val)) of proliferative epithelium, glandular secretory epithelium, epithelial transition, sPE ciliated epithelium and ciliated epithelium subpopulations. Average log2(FC) is represented by the color scale; dot size represents the percentage of cells expressing that gene.

Differences in the clustering of stromal and epithelial cells were immediately apparent; the samples from the former patients with sPE lacked subpopulations that were more prominent in the controls, and vice versa. This finding prompted us to perform a detailed comparison of these cell types from the two sources.

Endometrial cell differentiation defects in sPE in stroma

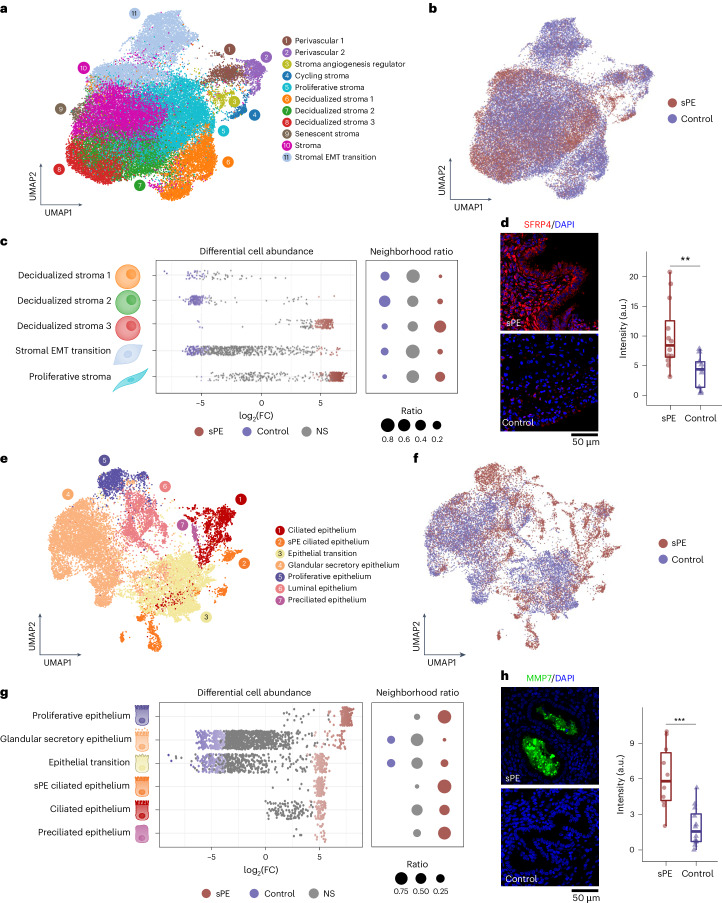

Integration of the stromal and perivascular cell transcriptomes identified several subpopulations (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 5). Decidualized stroma 1 cells expressed genes related to ribosome activity (RPS29 and RPL37A) and progesterone-associated endometrial protein (PAEP). Decidualized stroma 2 cells co-expressed markers of the predecidual and decidual states, EGR1 and CXCL2 (refs. 3,28,29), respectively. Decidualized stroma 3 cells expressed well-known decidualization markers (such as IGFBP1 and TIMP3 (ref. 30), and ATF3 (ref. 31)) and transcription factors associated with late decidualization, including CSRNP1 (ref. 3).

Fig. 2. Altered stromal and epithelial cell differentiation states of DR in patients with sPE.

a, UMAP of cell subpopulation identification of stromal and perivascular fractions of endometrium in the late secretory phase. b, UMAP of stromal merged cells of both sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 12) samples. c, Beeswarm plot of differential cell abundance by stromal cell subtypes. The x axis represents the log2(FC) in the abundance of sPE. Significant changes in cell abundance in each condition are represented in colors. Gray dots annotated as ‘NS’ represent not significant changes. d, IF validation of SFRP4 in sPE (n = 4) versus control (n = 4) samples and quantification of fluorescence intensity. Four biological replicates were conducted for each condition, with three technical replicates assessed for each biological replicate. In each boxplot, horizontal lines denote median values; boxes extend from the 25th to the 75th percentile; dots are the observations, and whiskers represent the s.d. Two-sided Wilcoxon statistical analysis (**P = 0.0073). e, Cell subpopulation identification of epithelial fraction of endometrium in the late secretory phase. f, UMAP of epithelial merged cells of both sPE and control samples. g, Beeswarm plot of differential cell abundance by epithelial cell subtypes. The x axis represents the log2(FC) in the abundance of sPE. Each dot represents a neighborhood; neighborhoods colored in blue represent those with a significant decrease in cell abundance in sPE conditions, while red dots are enriched in sPE samples. Gray dots annotated as ‘NS’ represent not significant changes. h, IF validation of MMP7 in sPE (n = 4) versus control (n = 4) samples and quantification of fluorescence intensity. Four biological replicates were conducted for each condition, with three technical replicates assessed for each biological replicate. Two-sided t test statistical analysis (***P = 0.0007). a.u., arbitrary units.

We also identified a stroma epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) subpopulation; this cluster expressed PDGFRA that is involved in endometrial regeneration30. Another cluster is the proliferative stroma expressing markers of the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle—SFRP4 (ref. 32), MMP11 (refs. 33,34), DIO2 (ref. 35), SFRP1 (ref. 36) and PGRMC1 (ref. 37). We also captured two distinct perivascular cell subpopulations closely related to stromal cells during decidualization. The perivascular 1 (STEAP4+) and perivascular 2 (MYH11+) subpopulations clustered near cells that regulate stromal angiogenesis that expressed CCBE1, a regulator of VEGFC38,39.

Mapping of cell identity allowed the identification of subpopulations that were differentially abundant in sPE or control samples (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Decidualized stroma 1, 2 and the stromal transition subpopulation were enriched in control samples, whereas decidualized stroma 3 and proliferative stroma were increased in sPE samples. This mosaic state—proliferative stromal cells (MMP11+ and SFRP4+) coexisting with IGFBP1+ decidualized cells—appears to be the hallmark of DR in sPE (Fig. 2c).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Neighborhood graph represents the differential cell abundance.

(a) Stromal and perivascular cells, (b) epithelial cells and (c) epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in late secretory endometrium. Dot size represents neighborhoods, while edges depict the number of cells shared between neighborhoods. Neighborhoods colored in blue represent those with a significant decrease in cell abundance in sPE and red highlights cells enriched in sPE. (d) Gene ontology analysis including altered genes from all cell subtypes labeled as sPE ciliated epithelium population. Dot size represents the number of DEGs involved in each biological process; color represents the general category to which the biological process is related. Enrichment index was calculated by −log(adj p value). Adjusting method was FDR, and threshold set was <0.05.

In patients with sPE, TIMP3 is upregulated in the decidual stroma 1 and 2, while IGFBP1 and IGFBP6 are upregulated in the decidual stroma 3. The proliferative stroma subpopulation showed increased expression of SFRP4 and FOS, markers associated with the proliferative phase40 and endometriosis41 (Supplementary Table 6). Immunofluorescence (IF) confirmed higher stromal SFRP4 in former patients with sPE compared to controls (Fig. 2d).

These results point to an imbalance in stromal populations in sPE with a predominance of proliferating stromal cells coexisting with decidualized cells in a proinflammatory niche.

Endometrial cell differentiation defects in sPE in epithelia

We integrated the epithelial cell transcriptomes, identifying the following epithelial cell subtypes (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 7): ciliated epithelium, preciliated epithelial cells and sPE ciliated epithelium. Ciliated epithelium expressed TPPP3, RSPH1 and C1orf194; additionally, these cells expressed FOXJ1 and PIFO as previously shown3. Preciliated epithelial cells expressed CDC20B and CCNO3. We also identified specific PDGFRA+ ciliated epithelial cells present only in former patients with sPE (sPE ciliated epithelium).

Specifically, gene ontology (GO) analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in this cell subpopulation revealed key biological features of ciliated epithelium, including extracellular matrix (ECM) and cilium organization, epithelial proliferation and wound healing (Extended Data Fig. 5d). The population transitioning between epithelium and stroma expressed stromal markers like TIMP3 and DCN. Luminal epithelial cells were identified by TGS1 and MSLN, while glandular secretory cells, the most abundant type, expressed PAEP, CXCL14 and SPP1. A subpopulation of epithelial cells also showed markers of the proliferative phase, including IHH, MMP7 and EMID1. DEGs of epithelial subtypes are detailed in Extended Data Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 8.

The proliferative epithelium, preciliated, ciliated epithelium and sPE ciliated epithelium subpopulations were more numerous in patients with sPE (Fig. 2f,g and Extended Data Fig. 5b). Ciliated epithelial cells increase during the proliferative phase42, suggesting abnormal epithelial differentiation in DR. Cell types that were enriched in the control group (glandular epithelial cells and epithelial transition) comprised a small fraction of the sPE samples. The results confirmed significant differential abundances of the aforementioned cell types.

In the proliferative epithelium of former patients with sPE, VIM, progesterone receptor (PGR) and MMP7 were upregulated. IF confirmed a significant increase in MMP7 in endometrial tissue from patients with sPE (Fig. 2h). The sPE epithelium subpopulation was characterized by upregulation of SRFP4 and IGF1 and downregulation of CXCL14, PAEP and TIMP3; the ciliated epithelial cells downregulated MT1G, CXCL14 and GPX3. As to the subpopulations that were less abundant in former patients with sPE, the glandular epithelium cells from these individuals had dysregulated expression of several secretoglobins and reduced mRNA levels of the transcriptional regulator MECOM. Also, epithelial transition cells had higher expression of SERF4, FOS and JUN and lower expression of CXCL14 and TIMP3, among others.

Altogether, we confirm that there is a notable imbalance in epithelial populations in patients with a history of sPE, characterized by predominantly aberrant proliferative epithelium and ciliated epithelium coexisting with glandular secretory and luminal epithelium in conjunction with aberrant epithelial cell types that might contribute to the epithelial phenotype observed macroscopically and microscopically.

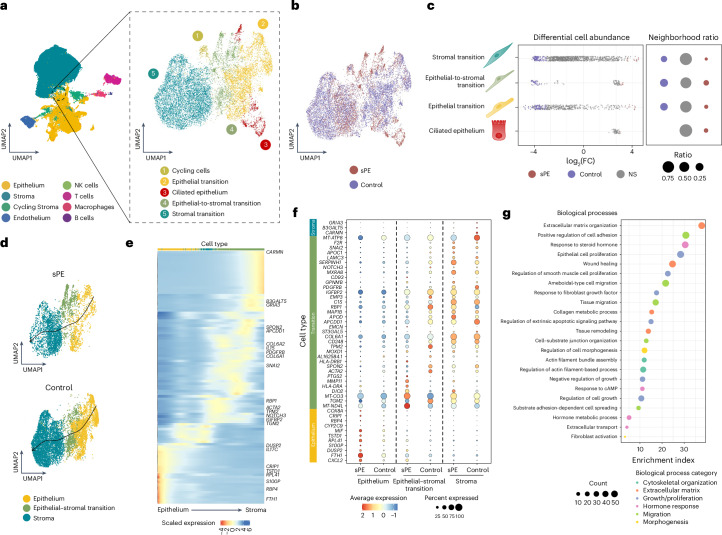

Defective epithelial-to-stromal transition in sPE

We integrated the transcriptomes of the subpopulations of the epithelia to the stroma transition zone (Fig. 3a) and projected in a UMAP comparing cases and controls (Fig. 3b). This analysis included stroma, epithelium, epithelial–stromal transition, ciliated epithelium and cycling cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 9). The differential abundance analysis (Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Fig. 5c) revealed an increased number of cells from controls in EMT that were greatly reduced in patients with sPE.

Fig. 3. Absence of EMT in endometria with DR from patients with sPE.

a, Zoom-in of EMT and cell subpopulation identification of endometrium in the late secretory phase. Circle highlights the epithelial-to-stromal transition subpopulation. b, UMAP of EMT merged cells of both sPE and control samples. c, Beeswarm plot of differential cell abundance by EMT cell subtypes. The x axis represents the log2(FC) in the abundance of sPE. Significant changes in cell abundance in each condition are represented in colors. Gray dots annotated as ‘NS’ represent not significant changes. d, RNA velocity generated with scVelo of sPE and control samples of epithelial transition, epithelial-to-stromal transition and stromal transition subpopulations. The ciliated cell subtype was removed from trajectory inferences in downstream analysis. Arrows represent the cell trajectories across clusters, inferring differentiation cell trajectories. e, Expression patterns of landmark genes of the lineage 1 differentiation process. Average log2(FC) is represented by the color scale and cell subtypes by color. f, Dot plot of DEGs in sPE versus controls identified across pseudotime associated with stroma, epithelial-to-stromal transition and epithelium (color represents the average expression, and dot size refers to the percentage of cells of each cluster expressing each marker). g, GO analysis including DEGs from all cell subtypes labeled as EMT populations. The enrichment index was calculated by log(adjusted P). The adjusting method was FDR, and the threshold set was <0.05.

To delve deeper into understanding the epithelial-to-stromal transition, we performed RNA velocity. The results revealed a temporal dynamic transcriptional process originating from epithelial cells and extending to stromal cells. Lineage 1, representing the most interesting progression alongside the epithelium, epithelial–stromal transition and stroma cell populations, was projected in samples from patients with sPE and control participants (Fig. 3d,e and Extended Data Fig. 6). In samples from control participants, there was a clear transition from secretory glandular epithelium to stroma, describing an EMT associated with the late secretory decidual state, whereas in samples from patients with sPE, significant density disturbances appear to be associated with DR. Finally, differential expression between conditions highlighted the substantial contribution of controls to the transition (Fig. 3f). GO analysis of DEGs revealed enriched biological processes related to EMT, such as cytoskeletal organization, ECM organization, growth/proliferation balance, migration and morphogenesis43, as well as hormonal response (Fig. 3g). These results suggested not only a decrease but also a dysregulation of fundamental aspects of stromal cell transition to an epithelial phenotype in endometrial samples collected from former patients with sPE.

Extended Data Fig. 6. RNA velocity recapitulates dynamics of epithelial-to-stromal transition.

(a) The observed and the extrapolated future states (arrowheads) are shown. Cell subtypes are represented by color scale. (b) UMAP with the two computed lineages detected by Slingshot. Cell subtypes are represented by color scale, solid arrow represents lineage 1 and dotted arrow represents lineage 2. (c) UMAP with the computed pseudotime showing the differentiation vector map for lineage 1 and coupled with a density plot of each condition. (d) Histogram of the distribution of cells across the pseudotime. Counts (y axis) show the number of cells contributing to the pseudotime. (e) Expression patterns of landmark genes of the lineage 1 differentiation process. Average log2(FC) is represented by the color scale and cell subtypes by color.

Dysregulated cell-to-cell communications in sPE

In samples from patients with sPE, stronger signals were observed in the NRG, BMP, CX3C and EGF pathways, while control samples had stronger IL-1 and MADCAM signals. Overall, there was increased signaling among cells from former patients with sPE (Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 10).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Signaling pathways that are considered significant (p < 0.05) and enriched in the experimental group.

(a) Relative information flow (ratio). (b) Absolute value of biologically enriched pathways in each group. This analysis was made using the rankNet function and the results of the Wilcoxon test analysis. Estimation is based on the number of interactor molecules expressed (that is, ligand–receptor pairs) and the strength of this interaction (expression level; Methods). (c) Heatmap showing the contribution of signals to cell subpopulations in terms of cumulative outgoing signaling (sPE vs control). Bar graph illustrates the mapping of perturbations in communication networks to specific cell types. (d) Heatmap showing the contribution of signals to cell subpopulations in terms of cumulative incoming signaling (sPE vs control). Bar graph illustrates the mapping of perturbations in communication networks to specific cell types.

Then, we investigated the ligand–receptor pairs contributing to the sPE-associated cell-to-cell communication (CCC) network perturbations and the cell types that were involved. In control samples, endothelin-mediated signals are directed between the endothelium and glandular secretory epithelium to the various subtypes of stromal cells (Fig. 4a). In endometrial samples from patients with sPE, however, the signals are mainly redistributed between epithelial early proliferative and different stromal cell subpopulations, involving a weakening of EDN1–EDNRA and the emergence of EDN3–EDNRB signaling (Fig. 4b). Canonical and noncanonical WNT (ncWNT) signals are key regulators of decidualization. In control samples, the stromal transition subpopulation strongly self-regulates and communicates with endothelial and perivascular cells. In endometrial samples from patients with sPE, these signals are diminished, leading to new autocrine proliferative regulation (Fig. 4c), and the involvement of new ligand–receptor pairs like WNT5A–FZD10 (Fig. 4d). Canonical WNT signaling in control samples mainly involves autocrine regulation of stromal transition cells and communication with decidual stromal cells. In patients with sPE, stromal transition cells and early secretory stromal cells signal to undifferentiated stromal cells (Fig. 4e), involving at least four canonical WNT ligand–receptor pairs not active in control samples (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4. Dysfunctional cell-to-cell communication networks associated with altered cell composition in DR.

a,c,e,g,i, Chord plots displaying the CCC network of EDN (a), ncWNT (c), canonical WNT (e), semaphorin (SEMA3; g) and SPP1 (i) in sPE and control samples. Each colored dot represents a cell subtype. Color arrows represent the incoming signaling, and the thickness of the lines refers to the strength of the signal between cell subtypes. b,d,f,h, Bar plot of each ligand–receptor pair contributing to the CCC of EDN (b), ncWNT (d), WNT (f) and SEMA3 (h). j, IF validation of SPP1 in sPE (n = 4) versus control (n = 4) samples and quantification of fluorescence intensity. Four biological replicates were conducted for each condition, with three technical replicates assessed for each biological replicate. Two-sided t test statistical analysis (**P = 0.006). EDN, endoglin.

Significant changes were also observed in SEMA3A and SPP1. In samples from the control group, SEMA3A signaling, which is highly expressed in the proliferative phase44, was mainly restricted between stromal and endothelial cells. However, in samples from patients with sPE, these signals shifted toward proliferative epithelial cells and other cell types, with new pathways emerging. SPP1, which is highly expressed during the mid-late secretory phase by epithelial cells45, typically autoregulated by epithelial, stromal cells and glandular epithelium, showed reduced signaling in patients with sPE (Fig. 4i). IF confirmed decreased SPP1 in glandular epithelium of patients with sPE (Fig. 4j). Additionally, tenascin signaling, normally between stromal and epithelial cells, exhibited new interactions in patients with sPE, highlighting extensive signaling alterations (Extended Data Fig. 8f).

Extended Data Fig. 8. ROI classification in endometrial tissue.

(a) One representative sPE patient and (b) one representative control. Venn diagrams of the DEGs from the single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analysis. (c) DEGs from stromal and endothelial cells overlapped with DEGs from enriched stromal ROIs. (d) DEGs from stromal, endothelial and epithelial cells overlapped with DEGs from enriched glandular epithelial ROIs. (e) DEGs from stromal, endothelial and epithelial cells overlapped with DEGs from enriched luminal epithelial ROIs. (ROIs refer to regions of interest). (f) Chords plots displaying the CCC network of TENASCIN in sPE and control. Each colored dot represents a cell subtype. Color arrow represents de incoming signaling, and the thickness of the lines refers to the strength of the signal between cell subtypes.

In conclusion, these data suggest that in the endometrium of patients with DR, there is a very significant rewiring of signaling pathways with respect to molecules and cell types. Majorly, the proliferative phenotype of cells leads to aberrant decidualization.

Spatial transcriptomics of DR in sPE

We spatially resolved the transcriptomic changes by spatial transcriptomics on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded late secretory endometrium, analyzing 95 regions of interest (ROIs) in sPE (n = 8) and controls (n = 8). ROIs were regions classified in the following three categories based on the endometrial tissue architecture (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b): (1) enriched in stromal (VIM+) and endothelial cells (CD31+; Fig. 5a), (2) enriched in the glandular epithelium (PanCK+; Fig. 5c) and (3) luminal epithelial regions enriched in luminal epithelium and stromal cells (PanCK+ and VIM+; Fig. 5e). Differential expression analysis (patients versus controls) revealed (Supplementary Table 11; 1) 430 DEGs in stromal ROIs, (2) 575 DEGs in glandular epithelium ROIs and (3) 456 DEGs in luminal ROIs. With a few exceptions, sPE and control samples clustered separately.

Fig. 5. DR in samples from patients with sPE confirmed with spatial transcriptomics.

a, IF of enriched stromal ROIs selected of one representative sPE sample and unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on Pearson distances of the normalized data z scores of the top genes of enriched stromal ROIs. b, Volcano plots depicting DEGs between sPE and controls within stromal ROIs. c, IF of enriched glandular epithelial ROIs selected of one representative sPE sample and unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on Pearson distances of the normalized data z scores of the top genes of enriched glandular epithelium ROIs. d, Volcano plots depicting DEGs between sPE and controls within glandular epithelial ROIs. e, IF of enriched luminal epithelial ROIs selected from one representative sPE sample and unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on Pearson distances of the normalized data z scores of the top genes of enriched luminal epithelium ROIs. f, Volcano plots depicting DEGs between sPE and controls within luminal epithelial ROIs. Heatmap legend reflects info of groups (sPE in red and control in blue), and colors represent the ROI of each participant. LMM was applied to obtain DEGs. Volcano plot legend represents significant genes (P < 0.05) and NS genes (NS < 0).

We coalesced the DEGs from scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics analyses (Extended Data Fig. 8c–e). In general, the DEGs had the same pattern of upregulation or downregulation in both analyses, which cross-validated the findings. In the enriched stromal ROIs (Fig. 5b), DEGs identified by both technologies included those involved in cytoskeletal organization. TPM1 (ref. 46) was downregulated, as were MYL9, which increases decidual contractility, and ANXA2, previously associated with DR15. SEMA3, identified in CCC analysis, was upregulated as was KDM6b, which is involved in regulating decidual DNA methylation and modulating target gene expression47.

The glandular epithelium ROI genes (Fig. 5d) were upregulated in patients with sPE and shared with the scRNA-seq analysis of epithelium, including TNFRSF21 and the GREB1 receptor. They are also upregulated in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and endometriosis48.

The luminal epithelium ROI genes (Fig. 5f) that were upregulated in patients with sPE and shared with stroma scRNA-seq included LIMA1 (ref. 49), SCARB1 and MMP7 (ref. 33). MMP7 is upregulated in luminal epithelial ROIs as well as in single-cell analysis, associated with the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle33. IF analysis of MMP7 in patients with sPE cross-validated the results obtained by scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics (Fig. 2h). DUSP2 and ACADSB also shared this pattern.

Altogether, coalescing the scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics data pointed to an imbalance of cells in the epithelial and stromal compartments from the patients with sPE attributable to late secretory endometrium, retaining characteristics of the proliferative phase. Specifically, our results suggested dysregulation of fundamental aspects of epithelial cell transition to a stromal phenotype during decidualization.

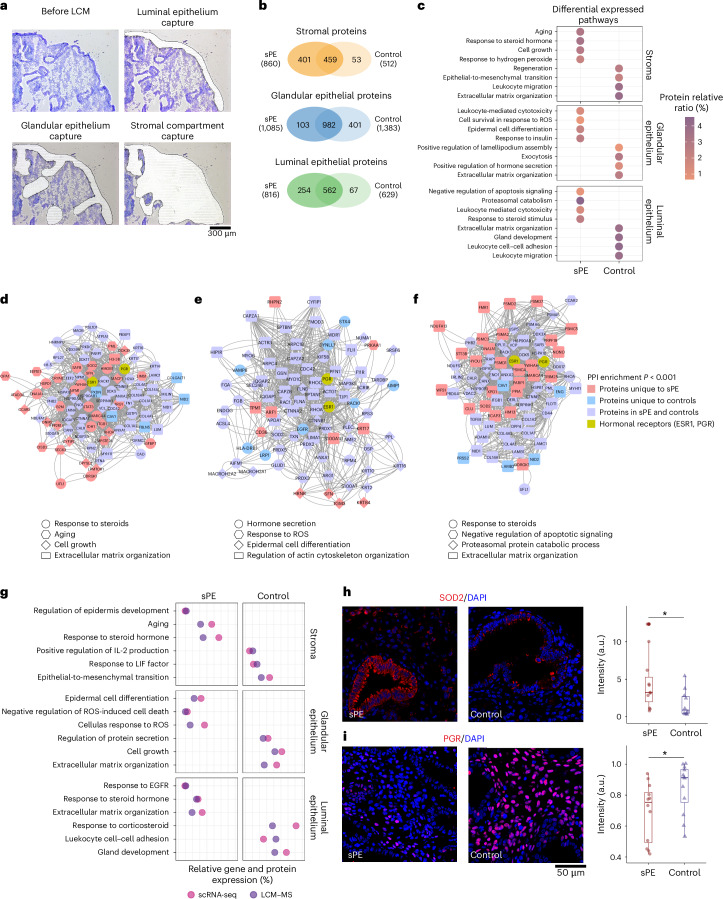

Spatial proteomic of DR in sPE

We used LCM–MS to analyze the glandular epithelium, luminal epithelium and stroma of endometrium obtained during the late secretory phase from an independent cohort of donors (sPE, n = 7; controls, n = 10; Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 12).

Fig. 6. Differential endometrial proteome associated with DR in patients with sPE compared to controls.

a, Endometrial section before laser capture microdissection and after isolating the ROI. Black solid line shows the isolated regions (sPE n = 7 and control n = 10). b, Venn diagrams showing the total number of proteins identified between sPE and controls in the stromal, glandular epithelium and luminal epithelium compartment. c, Differential expressed pathways specific to controls and sPE per region analyzed. Color gradient shows the protein ratio (%), which refers to what proportion of all the proteins detected in the region are proteins involved in the pathway. All pathways included are significantly enriched (adjusted P < 0.05). d, PPI network including those proteins involved in highlighted pathways in the stromal compartment. e, PPI network including those proteins involved in highlighted pathways in the glandular epithelium. f, PPI network including those proteins involved in highlighted pathways in the luminal epithelium. Colors show the specificity of proteins is indicated as follows: proteins unique to sPE, to controls, shared by both groups and ESR1 and PGR. Shape denotes the pathways. g, Dot plot showing the functional enrichment coincides between the spatial proteome (LCM–MS) and the DEGs at single-cell resolution (scRNA-seq). Left: sPE-specific pathways. Right: control-specific pathways. h, IF validation of SOD2 in sPE (n = 4) versus control (n = 4) samples and quantification of fluorescence intensity. i, IF validation of PGR in sPE (n = 4) versus control (n = 4) samples and quantification of fluorescence intensity. Four biological replicates were conducted for each condition, with three technical replicates assessed for each biological replicate. Two-sided Wilcoxon test statistical analysis (*P = 0.03). PPI, protein–protein interaction.

The stromal compartment had the highest number of differentially expressed proteins. Of these, 401 (43.9%) were specific to samples obtained from patients with sPE, and 53 (5.8%) were unique to control samples (Fig. 6b). Among proteins specific to sPE samples was STAT3, which participates in decidualization downstream of PGR and is aberrantly increased in endometriosis50,51. Response to steroid hormones, particularly estrogens, is enriched in the sPE group, as in aging and cell growth (Fig. 6c), consistent with increased proliferation and supported by the differential expression of markers of cell proliferation in tumorigenesis such as ARG1 and B2M. Controls group showed an enrichment for ECM organization and EMT. The analysis of the protein–protein interaction network identified estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and STAT3 as hub proteins, supporting the central role of hormonal signaling in the sPE-affected pathways (Fig. 6d).

The glandular epithelium of controls had 401 (27%) unique proteins, while 103 (6.9%) were only present in sPE samples and 982 were common to both groups (Fig. 6b). The proteome from controls was enriched for hormone secretion, whereas the sPE proteome was enriched for cell survival in response to ROS and epithelial cell differentiation (Fig. 6c). The protein–protein interaction network revealed that these pathways are significantly interconnected with ESR1 and PGR (Fig. 6e). Thus, disrupted hormonal signaling could drive an imbalance in proliferation/differentiation, affecting the secretory function of endometrial glands by mechanisms that include the generation of ROS and defective cytoskeletal organization. Notable proteins related to this phenotype were specific to controls such as EGFR and LRP1. Moreover, IF staining of PGR in the stromal compartment demonstrated a reduced expression in patients with sPE compared to controls (Fig. 6i), reinforcing the hormonal disruption affecting this condition.

The majority of luminal epithelium proteins, 562 (63.3%), were shared between patients and controls; 67 (7.6%) were unique to controls, and 254 (28.8%) were specific to cases (Fig. 6b). This proteome was enriched for response to steroids, specifically estrogens (Fig. 6c), the major hormone during the proliferative phase. Accordingly, proteins specific to sPE were involved in cell proliferation, increased metabolism and, consequently, inhibition of apoptosis signaling. In contrast, proteins unique to controls were enriched for ECM organization. Then, we built a network with proteins involved in representative features of these pathways that were significantly disturbed in sPE (Fig. 6f). The results supported strong interconnections among these pathways and the key role of ESR1 and PGR.

Finally, we identified intersections between the biological processes identified by the scRNA-seq and LCM–MS analyses (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Table 13). There was substantial concordance between the two datasets in terms of those that were specific to sPE samples or controls. In many cases, there was also an overlap in the related biological processes that mapped to two or more compartments. The sPE group was characterized by processes/molecules involved in epidermal regulation, responses to oxidative stress/ROS and aging. The control group was characterized by processes such as protein secretion, cell growth, ECM organization, leukocyte adhesion and IL-2 production. The sPE group was also notable for the absence of processes that were significantly represented in the control group, such as gland development, response to leukemia inhibitory factor and EMT.

Thus, by overlapping the proteomic-based pathways associated with sPE and control samples with the DEGs from the single-cell dataset, we confirmed the key molecular features that shape DR at a multi-omic level. Single-cell analysis revealed an upregulation of SOD2 in the stromal compartment of sPE samples, which was also enriched in the stromal compartment of sPE in the proteomics analysis. We corroborated these findings by IF demonstrating a significant increase of fluorescence intensity in patients with sPE compared to controls (Fig. 6h). Overall, the main features are an imbalance in proliferation/differentiation in various regions of the endometrium, associated with a disturbed response to steroid hormones, particularly estrogens, which could ultimately affect epithelial–stromal crosstalk and the secretory function of glands. Altogether, these results provide the deepest characterization of DR to date with possible clinical implications not only in the understanding of the pathogenesis of sPE but also in endometriosis and other pathological conditions related to DR.

Discussion

Most pregnancy disorders originate from alterations in the periconceptional period, at the time when trophectoderm invades the decidualized endometrium1. Defective trophoblast invasion is the primary underlying cause of several obstetrical syndromes such as PE, IUGR or preterm labor52. In a bid to understand abnormal placentation in these relevant pathologies, our group and others have identified a decidualization defect in the endometrium of these patients as a contributing factor in these obstetrical conditions4, including sPE15,16,53, late-onset PE54, IUGR or placenta accreta spectrum disorder19.

This study offers a comprehensive exploration of the DR condition in former patients with sPE, shedding light on the associated changes at gross, microscopic, scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics and proteomics by LCM–MS. Our findings underscore the intricate molecular landscape underlying DR, implicating not only alterations in stroma and epithelium but also aberrations in the epithelial-to-stromal transition.

Distinct morphological features, such as glandular dilation and a higher cell count in tubular and tubuloalveolar glands, hinted at underlying endometrial changes from former patients with sPE. scRNA-seq revealed significant shifts in cellular composition and differentiation patterns. In stromal cells, our analysis revealed a shift in the balance leading to a mosaic of proliferative and decidualized stromal cells in former patients with sPE corroborated by aberrant gene expression, with increased markers of proliferation and decreased decidualization markers. Endothelial and immune cells showed transcriptomic signs of inflammatory dysregulation. In epithelial cells, there was an increased presence of proliferative and ciliated cells, and gene expression patterns mirrored this imbalance, indicating disrupted differentiation and maturation, potentially affecting the production of uterine fluid essential for nutrient supply and antimicrobial protection for the implanting conceptus.

Our analysis also uncovered perturbations in the epithelial-to-stromal transition, emphasizing a significant reduction in cells involved in this transition in former patients with sPE. Furthermore, dysregulated cell–cell communication networks were evident, with notable alterations in signaling pathways critical for decidualization such as WNT or SPP1, angiogenesis and hormonal regulation.

Spatial transcriptomics and proteomics analyses provided additional layers of insight, highlighting spatially specific dysregulation in both epithelial and stromal compartments, mainly related to proliferation/differentiation imbalance. Key pathways implicated in DR, including hormonal signaling—particularly in response to estrogens and progesterone─oxidative stress response and cytoskeletal organization, were identified, corroborating findings from single-cell analyses. Specifically, PGR signaling is reduced in the stromal compartment of sPE samples as previously demonstrated by our group16. This impaired hormonal signaling contributes to the DR observed in sPE, highlighting the importance of hormonal regulation in maintaining endometrial function.

The comprehensive characterization of DR presented in this study not only advances our understanding of the pathogenesis of sPE but also has broader implications for other obstetrical syndromes and prevalent gynecological diseases, such as endometriosis9,10 and recurrent miscarriage13.

The identified molecular signatures of the underlying mechanisms involved in decidual progesterone inaction may serve as potential biomarkers for preconceptional detection of DR and intervention strategies before pregnancy is established55. Furthermore, tackling this common issue of progesterone signaling disturbances may be relevant for managing and treating endometriosis and/or recurrent pregnancy loss.

The strength of our study lies in the use of a multi-omic strategy to unravel the cellular and molecular characteristics of DR associated with former patients with sPE. Nevertheless, the potential clinical implications of DR extend beyond a single pathological condition because it is the root of a spectrum of relevant obstetrical and gynecological conditions9–19. However, the current study has some limitations, such as the number of patients analyzed. Additionally, these results should be tailored to the target population for the specific conditions related to DR. This caveat further underscores the significance of customizing biomarkers to suit different subsets of obstetrical and gynecological diseases.

In summary, our multi-omic approach offers a nuanced depiction of DR, revealing an imbalance in proliferation/differentiation within the endometrium, disrupted response to steroid hormones—especially estrogens—and potential impacts on epithelial–stromal communication and glandular secretory function. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular underpinnings of DR and highlight potential preconceptional therapeutic targets for mitigating the occurrence of great obstetric syndromes.

Methods

Study design

In this study, we investigated endometrial samples from different cohorts of nonpregnant women who had a previous sPE pregnancy compared to those with a normal pregnancy, applying digital image analysis of H&E sections, scRNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics and spatial proteomics. For digital image analysis, endometrial tissue sections from former sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) patients were analyzed. For scRNA-seq, 11 patients and 12 controls were investigated. For spatial transcriptomics, eight patients with sPE and eight controls were investigated, and for the spatial proteomics analysis, seven sPE and ten controls were investigated (Extended Data Fig. 1). Endometrial tissue was collected during the late secretory phase of the cycle from women with a previous sPE pregnancy and control individuals who had normal obstetric outcomes (Supplementary Table 1). A two-tailed Student’s t test was applied between sPE and control clinical variables based on the normal distribution of data for each experiment.

sPE samples were classified according to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, based on high blood pressure (systolic > 160 mm Hg or diastolic > 100 mm Hg), thrombocytopenia, impaired liver function, renal insufficiency, pulmonary edema and/or cerebral/visual disturbances. Endometrial biopsies were collected during the late secretory phase (1–3 days before menstruation). Tissue segments were processed for various analyses—paraffin-embedded for digital image analysis, spatial transcriptomics, optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound-embedded for laser capture and mass spectrometry and cell isolation for scRNA-seq. Maternal parameters for each cohort are detailed in Supplementary Table 1a–c.

Sample collection

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee from the Clinical Research of the University and Polytechnic Hospital La Fe, Valencia, Spain (4 December 2019; protocol code IGX1-HUT-CS-19-07). Endometrial samples were collected from women aged 18–42, without any medical condition, who had been pregnant 1–8 years earlier. All donors had regular menstrual cycles (25–31 days) without underlying pathological conditions and had not received hormonal therapy in the 3 months preceding sample collection. Donors provided informed consent and were anonymized. Endometrial biopsies were obtained using a pipelle catheter (Genetics Hamont-Achel) under sterile conditions and preserved in HypoThermosol FRS (STEMCELL Technologies) at 4 °C until processing.

Digital image analysis

Paraffin-embedded endometrial tissue sections from former patients with sPE (n = 11) and control (n = 9) stained with H&E were digitized with a Pannoramic 250 Flash III slide scanner (3DHISTECH) at ×20 and analyzed using custom Groovy language scripts in QuPath (v0.5.1)56. A total of 3,756 gland sections (2,035 and 1,721 sPE and control, respectively) were accurately segmented using the brush and wand QuPath annotation tools, carefully leaving outside the selection of the surrounding stromal cells and assigning a gland ID number. Then, the lumen area including detached cells and secretions was selected and subtracted from the gland annotation to obtain a specific annotation for the gland epithelium. Epithelial cell nuclei from the gland epithelium were then detected using StarDist, a deep-learning extension script for star-convex nuclear detection based on pretrained datasets of H&E images56,57. Morphometric parameters from the lumen (area and solidity—the ratio of the area/convex area of the gland) and gland epithelium (number of cell nuclei) annotations were hierarchically assigned to each ‘parent’ gland section, together with gland parameters (area, maximum diameter and circularity—the ratio of a circle of the area/circle of the perimeter of the gland). The ratio of lumen and gland area was calculated as a percentage to obtain the portion of gland occupied by a lumen (percentage of lumen in the gland). The number of cell nuclei in gland epithelium was divided by gland perimeter to obtain the relative number of cell nuclei per 100 µm. To classify gland sections by size, the cutoff value of 200 µm corresponding to the 75th percentile value was selected. A specific script was used to establish the classification named as tubular (>200 µm) and tubuloalveolar (<200 µm) gland sections. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and were analyzed and represented using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 software. Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Sample processing

Endometrial biopsies were washed with PBS, minced and enzymatically digested with a solution containing 1 mg ml−1 Collagenase V (Sigma-Aldrich, C9263), 100 µg ml−1 DNase Type I (Roche, 03724751103) and 10% inactivated FBS in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium for 45 min at 37 °C and 175 rpm in a shaker platform. Digestion was inactivated by adding an equal volume of complete medium (10% inactivated FBS in RPMI medium). The solution was filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer, with the flow-through containing the stromal fraction and the strainer retaining the epithelial fraction. The stromal fraction was centrifuged for 5 min at 664g, and the pellet was washed with PBS. Then the pellet was resuspended into red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer (1×; eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min at room temperature to eliminate blood. The cell fraction was washed with PBS and then centrifuged for 5 min at 664g, resuspended with 200 µl of 0.04% BSA in PBS (wt/vol) and filtered using a 40-µm Flowmi filter (BAH136800040-50EA, Merk) for single-cell suspension.

The epithelial fraction was recovered by flushing 15 ml PBS to the inverted cell strainer into a 50-ml falcon tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 664g. It was digested with 5 ml of 100 µg ml−1 DNase Type I (Roche, 03724751103) in 0.25% Trypsin–EDTA solution (Life Technologies, 25200072) for 10 min at 37 °C and 175 rpm shaking. After inactivation with complete medium, the suspension was filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer, the filter was washed with 5 ml PBS and the solution was centrifuged for 5 min at 664g and treated with RBC lysis solution if needed. The final epithelial suspension was washed with PBS, resuspended with 200 µl of 0.04% BSA in PBS (wt/vol) and filtered using a 40-µm Flowmi filter.

Single-cell processing

Cell suspensions were stained with Trypan blue dye and counted for alive cell concentration in an automatic cell counter (EVE, NanoEnTek). Stromal and epithelial cells were mixed (1:1), and a total of 17,000 cells were loaded on a 10× Chromium (10x Genomics) onto a 10× G Chip to obtain gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs) containing individual cells. GEMs were used to generate barcoded cDNA libraries (Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kit v3.1; 10x Genomics) and quantified using the TapeStation High Sensitivity D5000 kit (Agilent). Following that cDNA (1–100 ng) was obtained to construct gene expression libraries that were quantified by the TapeStation High Sensitivity D1000 kit (Agilent), determining the average fragment size and library concentration. Libraries were normalized, diluted and sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina).

scRNA-seq data processing and filtering

Raw sequences were demultiplexed, aligned and counted using CellRanger software suite (v6.0.2) for whole-cell gene expression calculations, which takes advantage of intronic reads to improve sensitivity and sequencing depth (human reference genome GRCh38-2020-A). Low-quality droplets and barcodes were filtered out in the following four quality control (QC)-based consecutive steps throughout the analysis: (1) low unique molecular identifier-count barcode removal using an EmptyDrops-based method; (2) cells marked as doublets by DoubletFinder (2.0.3) and scds (1.6.0) tools—the hybrid approach from the scds R package was used to avoid removing false-positive doublets; (3) cells with median absolute deviation >3 in two of three basic QC metrics—number of detected features, number of counts and mitochondrial ratio. These cell-to-count matrices were integrated and corrected using Seurat and scVI functions, as described below. A final filtering step, (4), was applied alongside different rounds of clustering, where the obtained clustered cells with less than 750 features per cell, more than 25% mitochondrial ratio and/or showing a pattern of high doublet-scoring plus no gene marker-associated expression (during manual cell-type annotations) were also removed (Supplementary Table 3). Then, a detailed examination of erythroid genes (HBB and HBA2) was conducted in every cluster, corroborating that no erythroid cells were present in the analysis. Also, we examined every cluster, proving a balanced expression of mitochondrial genes, markers of cellular damage and stress-related genes like MALAT1 or ubiquitin genes compared with cell-type-associated genes. A total of 65,381 high-quality cells were integrated and projected within the UMAP. From those, 28,154 cells formed the sPE group, and 37,227 cells formed the control group. We address the different batch effects in the global, stromal and epithelial integrations for the patient investigated (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c), age (Extended Data Fig. 9d–f) and time since last pregnancy (Extended Data Fig. 9g–i).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Single-cell integration labeled by patient.

(a) Global, (b) stroma and (c) epithelium. Single-cell integration labeled by age of the donor of (d) global, (e) stroma and (f) epithelium. Single-cell integration labeled by time since last pregnancy of (g) global, (h) stroma and (i) epithelium.

Integration of single cells across conditions and clustering

As a first clustering analysis approach, read count matrices per sample were merged and processed following Seurat’s default pipeline (package v4.1.3). After normalization, the first 30 principal components on the 4,000 highly variable genes were used for dimensional reduction; cells were clustered and projected onto the UMAP. FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions were then applied for graph-based clustering by constructing a k-nearest neighbor graph using Euclidean distance in the principal component analysis space, which was then defined into clusters using the Louvain algorithm to optimize the standard modularity function. Clustree (R package v0.4.4) was applied to select the most stable clustering resolution. The first output of sample distribution in clusters and cluster marker genes was then explored to evaluate biases from our data batches. Next, we select the scVI python package (v0.19.0) to remove interindividual patient origin biases maintaining trajectories and removing batch effects58. The top 30 scVI components were used to embed and plot cells in the new reduced dimension space. These matrices were then input into Seurat’s clustering and differential expression protocol. Then, anchor transfer labels from Seurat were applied to propagate cell lineage labels from reference datasets to our data, enabling the identification of major cell types. The final annotation of each cell population was conducted by examining the expression of gene markers of specific cell types reported in the literature. This process was repeated in each integration.

Tissue cell composition and annotation of scRNA-seq datasets

The identification and labeling of major cell types was based on DEGs per cluster compared to the remaining clusters using the Wilcoxon rank sum test using an adjusted P value (by false discovery rate (FDR))59 of <0.05 and a log fold change (FC) of >0.5 or <−0.5. method. The primary cell populations were labeled by revising the expression of reported canonical markers from each cluster. The anchor transfer labels protocol from Seurat allowed the propagation of cell lineage labels from reference datasets to our data. This method facilitated the identification and annotation of the primary cellular lineages in our dataset. We transferred the main cell-type labels from our previously published single-cell datasets from controls60. Then, manual curation of canonical markers in the main cell types and cell subpopulations was performed using public datasets2,3,44,61 and the Human Protein Atlas (HPA)62. The main cell types were then subset separately—epithelium, stromal fibroblast, perivascular, cycling stroma, endothelium, macrophages, B cells, T cells and NK cells. Canonical markers of each cell type are displayed in a dot plot (Extended Data Fig. 3a)63,64. New clustering was performed on each to create the different zoom-ins that describe the contained subpopulations. The clustered zoom-ins were manually annotated by an extensive review of DEGs in the HPA database, single-cell atlases and scientific literature2,3,61,65. Regarding the stromal zoom-in, perivascular and stromal subpopulations have been demonstrated in mesenchymal cell types, both in vivo and in vitro66. Perivascular cells have been shown to play a crucial role in the decidualization process and to differentiate into stromal cells67. This is the reason for the decision to cluster both cell types in the same zoom-in. Genes with strong cluster specificity, as determined by a P value below 0.01, and the highest rank FC and percentage of expressing cells were considered. After defining each cell type with merged sPE and control samples, we additionally performed sPE and control annotation separately in the global, stromal and epithelial integrations to confirm that all cell types are represented in both conditions (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Extended Data Fig. 10. Single-cell integration labeled by cell type of global integration.

(a) All samples, (b) sPE and (c) control. Single-cell integration labeled by cell type of stromal integration for (d) all samples, (e) sPE and (f) control. Single-cell integration labeled by cell type of epithelial integration for (g) all samples, (h) sPE and (i) control.

Cell trajectories on the transcriptional pseudotimes

The inference of cell trajectories was based on the predicted velocity of mRNA synthesis in each cell. The method for calculating RNA velocity begins with obtaining the spliced/unspliced matrix using the Velocyto tool68. RNA velocities were separately obtained for each zoom-in clustering. As already stated in ref. 69, calculations using Velocyto are sensitive to genes that undergo sudden large changes in their expression patterns, described as transcription bursts. To avoid this issue, velocities computed by scVelo (v0.2.5) were corrected using CellDancer (v1.17; Extended Data Fig. 6a). In scVelo, we filtered the genes with fewer than 20 counts shared by cells in the filter_genes function and used only the top 2,000 most variable genes in the filter_genes_dispersion. We used the dynamic mode to compute cellular and velocity dynamics. In CellDancer70, we computed the velocities and projected the vector field predictions computed by the model onto the previously computed UMAP embedding space. After identifying the start and ends of the trajectories, we used Slingshot71 to compute the genes related to changes across pseudotime in the inferred trajectories (Extended Data Fig. 6b). We depicted this dynamic using Condiments72 obtaining two lineages (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). We identify genes whose expression patterns change along the pseudotime (Extended Data Fig. 6e).

Analysis of differential cell abundances and gene expression

To identify differential abundance in cell populations between sPE and control endometria, we used the MiloR (v1.6.0) tool described in ref. 73. This approach supports the grouping of cells on a k-nearest neighbor graph and evaluates the change in cell abundance between conditions; P values were adjusted using spatial FDR of <0.1. Spatial FDR is a statistical method used to control multiple testing in the context of spatially structured data. In scRNA-seq analysis, particularly when performing differential abundance analysis using tools like MiloR, spatial FDR accounts for the nonindependence of neighboring cells. We graphed the data as neighborhoods in which dots represent neighborhood sizes, and the weight of the connecting lines depicts the number of cells shared among neighborhoods visualized as a beeswarm plot (Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). Further differential gene expression analysis was performed using the model-based analysis of single-cell transcriptomics, where a contrast test was established for each cell type. We used an adjusted P value (by FDR) of <0.05 and a log2(FC) of >±0.5 (ref. 74; Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 4–9).

Analysis of cell-to-cell communication networks

In this study, we used the CellChat R package (v1.1.3) to infer the ligand–receptor pairs that were involved in endometrial CCC networks in the control versus the sPE datasets with statistical significance. The relative and absolute flow of information, calculated using the total interaction probability among all cell subpopulations in both conditions, is depicted in Extended Data Fig. 7a,b and Supplementary Table 10. Many of the outgoing (Extended Data Fig. 7c) and incoming signals (Extended Data Fig. 7d) in cells that comprised the sPE samples were largely absent in the comparable cell subpopulations from the control samples. This tool uses a curated database to infer the overall interaction probability and communication information flows based on the expression of specific ligand–receptor pairs. To elucidate, the total interaction probability measures the likelihood of communication between two cell types, where one serves as the sender and the other as the receiver. This estimation is based on the number of interactor molecules expressed (that is, ligand–receptor pairs) and the strength of this interaction (expression level).

Subsequently, the cumulative communication probability of all pairs in a pathway network is used to compute the communication information flow. To ensure robust results, pathways with fewer than ten cells were excluded from the analysis (10< cells per subpopulation). Additionally, we accounted for the impact of varying cell population sizes by enabling the ‘population.size’ argument in the ‘computeCommunProb’ function, which properly scales the communication weight of each subpopulation (set to TRUE).

We visualized cellular communication in sPE using chord plots, heatmaps and dot plots. Chord plots were created with the netVisual_aggregate function from the CellChat package (v1.1.3), excluding subpopulations without interactions (remove_isolate = TRUE; Fig. 4). Heatmaps display outgoing and incoming signaling patterns, generated with the netAnalysis_signalingRole_heatmap function (Extended Data Fig. 7).

Finally, we conducted a differential CCC analysis between control and PE samples using the ‘ranknet’ function, applying a significance threshold of 0.05.

Spatial transcriptomics sample processing

To achieve our objective, we used Nanostring technology with the GeoMx Human Whole Transcriptome Atlas panel, selecting ROIs to capture cellular diversity in the late secretory phase of the endometrium, including stromal, endothelial and epithelial cells.

We prepared 5-µm thick (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded) sections from 16 specimens, stained them with H&E and performed whole transcriptome analysis (WTA) following the NanoString experimental procedure. Using the H&E slides as a guide, we selected 95 ROIs, averaging 300 µm in size, categorized into three groups based on endometrial tissue architecture (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b).

For the WTA, the slides were first incubated at 60 °C for an hour, deparaffinized using limonene (Merck Chemicals and Life Science, S.A.U.) and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by subjecting the slides to 1× Tris–EDTA (pH 9) in a steamer for 20 min at 100 °C. Next, proteinase K (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM2548) was used to digest the samples at a concentration of 1 µg ml−1 for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, samples were postfixed in neutral-buffered formalin for 5 min.

Samples were hybridized overnight at 37 °C with a UV-photocleavable barcode-conjugated RNA probe set targeting 18,269 genes. After thorough washing to remove nonspecific probes, morphology markers were applied for counterstaining for 1 h at room temperature.

The morphology fluorescent markers were 1SYTO13 (1/10; NanoString), anti-panCK-Alexa Fluor 532 (1/50; NanoString), antivimentin-Alexa Fluor 594 (mouse, 1/100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-373717 AF594) and anti-CD31-Alexa Fluor 647 (mouse, 1/50; Abcam, ab215912) in blocking buffer W (NanoString). The IF images, ROI selection and spatially indexed barcode cleavage and collection were performed using a GeoMx DSP instrument (NanoString). The typical exposure times were 50 ms for SYTO13, 200 ms for anti-panCK AF532, 200 ms for antivimentin AF594 and 200 ms for anti-CD31 AF647. In total, 96 ROIs were collected.

For library preparation, we followed the manufacturer’s instructions, performing PCR amplification to add an Illumina adapter and unique dual sample indexes. Each molecule in the sequencing library corresponded to one cluster on the flow cell. The paired-end read strategy recommended by NanoString resulted in two paired-end reads, forward and reverse, per cluster, which can be described as one read pair. To achieve a minimum sequencing depth of 150–200 reads per square micron of illumination area, all WTA areas of interest (AOIs) were sequenced on a NextSeq 2000 (read type—paired-end; read length—read 1, 27 bp; read 2, 27 bp; index 1 (i7), 8 bp; index 2 (i7), 8 bp).

QC of spatial transcriptomics

Segments with fewer than 1,000 raw reads or less than 80% alignment, as well as ROIs with below 50% sequencing saturation, are excluded. The background count per segment is established using the geometric mean of unique negative probes in the GeoMx panel. No template control counts over 1,000 indicate potential contamination, but counts between 1,000 and 10,000 can be accepted if uniformly low (0–2 counts across probes). QC requires over 100 nuclei per segment, and all study segments meet this criterion. Outlier negative control probes are removed to improve background estimation and gene detection, resulting in 18,807 probes passing QC (one global outlier and seven local outliers detected). The limit of quantification (LOQ) for each ROI/AOI segment is based on negative control probes, calculated using the formula for n s.d. (n = 2 for this study).

| 1 |

In this dataset, we chose to remove segments with fewer than 10% of the genes detected. As a result, 0 segments were flagged and removed. In total, 0 segments were removed from the study from either segment QC or filtering.

In total, 10,239 targets were detected above LOQ in 10% or more of the segments. Including the genes of interest list, 10,489 targets in total were analyzed further. We filtered down to this number of targets.

Normalization and contrasting groups of spatial transcriptomics

Two common methods for normalizing GeoMx WTA/CTA data are as follows: (1) quartile 3 (Q3) and (2) background. Both estimate a normalization factor per ROI/AOI segment, with Q3 typically preferred due to its high correlation with the geometric mean of negative control probe counts. Q3 normalization was used for subsequent analysis.

For comparing differences between groups in GeoMx experiments, a linear mixed effect model (LMM) was used with slide as a random effect to account for nested, nonindependent sampling. This allowed us to adjust for the interdependence of multiple ROIs within tissue sections, unlike traditional statistical tests. Overall, there are two main types of LMM models when used with GeoMx data, which are as follows: (1) with a random slope for comparing features in the same tissue section and (2) without a random slope for mutually exclusive features.

Heatmaps of the DEGs for each compartment were constructed by unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on Pearson distances of the normalized data z scores.

Spatial proteomics processing

Three regions of each endometrial biopsy were isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM)—glandular epithelium, luminal epithelium and stroma. They were separately processed and analyzed using methods we previously published75. Briefly, frozen blocks of the tissue were sectioned (−20 °C) using a Leica CM3050 cryostat. Sections (20 μm) were mounted on Director slides (Expression Pathology76). Slides with sections were kept under dry ice until LCM the same day. Sections on slides were manually defrosted in room air (30 s), immersed in PBS until the OCT compound was completely removed (∼2 min), dipped in 0.1% toluidine blue for 30 s, washed in ice-cold PBS, dehydrated (30 s per treatment) in a graded ethanol series (75%, 95% and 100%) and then rapidly dried with compressed nitrogen.

Following capture, the samples were incubated in an alkaline surfactant-containing solution at 60 °C with rigorous vortexing every 15 min for 1 h. Iodoacetamide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to 15 mM and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. Proteins were digested overnight at 37 °C with trypsin (20 ng μl−1; Pierce) and then centrifuged at 16,000g (Eppendorf) for 10 min. Trifluoroacetic acid (Pierce) was added to the supernatant such that the final concentration was 0.5%. Duplicate technical replicates were performed along with a control that consisted of a blank Director slide that was carried through the entire sample preparation protocol.

Samples were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–ESI–MS/MS) using an Eksigent Ultra Plus nano-LC 2D HPLC system directly connected to an orthogonal quadrupole time-of-flight SCIEX TripleTOF 6600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX). Peptide and protein identifications were determined using the Paragon algorithm within the ProteinPilot search engine (v.5.0.2, SCIEX) against the corresponding proteome FASTA files obtained from UniProt. To decipher the underlying functions of the identified proteins, an overrepresentation analysis was performed.

Enrichment analysis

GO analyses were conducted to obtain biological processes using the enrichGO function from the clusterProfiler R package (v4.2.2). The input genes were those differentially expressed between the cell populations studied. The simplify function was then applied to reduce redundancy in the terms obtained, using a cutoff of 0.7 or 0.6 for semantic similarity and selecting the term with the lowest P adjusted. The P value adjustment method was FDR with a cutoff of 0.05 (FDR < 0.05). The input proteins were those described for both sPE and control groups per endometrial region (glandular epithelium, luminal epithelium and stroma). Specific pathways of a group refer to enriched pathways that are present in the controls or the sPE but are not present in the other group. The input genes were the differential expressed genes grouped by endometrial region. The P value adjustment method was FDR with a cutoff of 0.05.

Protein–protein interaction network

Protein–protein interaction networks were built to identify perturbations in endometria from the patients. In addition, ESR1 and PGR were included in the network to assess their associations with the DR phenotype.

The protein–protein interaction networks were created using the functional analysis suite String (v12.0) and visualized using Cytoscape software (v3.8.2). Hub genes were extracted using the maximal clique centrality and maximum neighborhood component of the cytoHubba plugin.

IF analysis

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were incubated overnight at 60 °C to produce wax melting and to improve tissue adherence. The sections were rehydrated according to conventional protocol with two rounds of xylene, ethanol in decreasing degrees (2× 100%, 90%, 70%, 50% and 30%) and, finally, ddH2O. Samples were treated using antigen retrieval buffer (Abcam, ab93678) boiling in a pressure cooker for 20 min. After cooling down samples, a photobleaching protocol was performed by immersing the samples in a photobleaching solution (NaOH 26.4 mM and 4.5% H2O2 in PBS) and exposing them in front of a powerful LED light for 45 min. This step was performed twice, and then samples were washed four times in PBS for 3 min. An incubation with blocking solution (5% BSA in PBS-Tween 0.1%) was performed at room temperature for 30 min before the incubation in primary antibody solution (antibody dilution is detailed in the ‘Antibodies’ section) in 3% BSA in PBS-Tween 0.1% overnight at 4 °C.

Then 15 min wash in PBS was performed three times. Following that another blocking solution was performed for 30 min at room temperature before the incubation in secondary antibody solution (secondary antibody diluted at 1/800 in 3% BSA in PBS-Tween 0.1%). A final wash was performed in PBS-Tween 0.1% before incubating with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 62247) at 400 ng ml−1 in PBS, followed by 15 min washes for two times and the mounting with Fluoromount-G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 00-4958-02).

Antibodies

The antibodies used in the study include anti-PGR (rabbit; Abcam, ab32085; 1/100), anti-MMP7 (rabbit; Abcam, ab207299; 1/300), anti-SFRP4 (rabbit; Abcam, ab154167; 1/200), anti-SOD2 (mouse; Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA1-106; 1/500), anti-SPP1 (rabbit; Abcam, ab63856; 1/200), goat antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor488; Abcam, ab150077; 1/800), goat antirabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 555; Abcam, ab176756; 1/800) and goat antimouse IgG (H + L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11001; 1/800).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (v4.3.1). Randomization and blinding were not necessary for this descriptive study. The sample size was carefully predetermined to ensure reproducibility. No sample was excluded from the analyses. Each endometrial sample was considered a biological replicate, and no technical replicates were performed in this study, except for the IF experiments. For the image analysis, 11 patients with sPE and 9 control biological replicates were assessed. For single-cell experiments, there were 11 patients with sPE and 12 control biological replicates. In spatial transcriptomics, there were 8 biological replicates for sPE and 8 for controls, while spatial proteomics included 7 biological replicates for sPE and 10 for controls. For IF analysis, 4 patients with sPE, 4 control biological replicates and 3 technical replicates per sample were quantified. All experiments were successfully completed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41591-024-03407-7.

Supplementary information