Abstract

Objective:

This study examined prospectively the effect of workplace violence on musculoskeletal symptoms among nursing home workers.

Background:

Previously we reported a cross-sectional relationship between physical assaults at work and musculoskeletal pain. This follow-up provides stronger evidence of the effect of workplace violence on musculoskeletal outcomes within the same workforce over two years.

Method:

Nursing home workers who responded to three consecutive annual surveys formed the study cohort (n = 344). The outcomes were any musculoskeletal pain, widespread pain, pain intensity, pain interference with work and sleep, and co-occurring pain with depression. The main predictor was self-reported physical assault at work during the 3 months preceding each survey. Prevalence ratios (PRs) were assessed with log-binomial regression, adjusting for other workplace and individual factors.

Results:

Every fourth nursing home worker, and 34% of nursing aides, reported persistent workplace assault over the 2 years. Among respondents assaulted frequently, two thirds experienced moderate to extreme musculoskeletal pain, and more than 50% had pain interfering with work and/or sleep. Baseline exposure to assault predicted pain outcomes 1 year later. Repeated exposure was associated with a linear increase over 2 years in the risks of pain intensity, interference with work, and interference with sleep; co-occurring pain and depression had an adjusted PR of 3.6 (95% CI = 1.7–7.9).

Conclusion:

Workplace assault, especially when repeated over time, increases the risk of pain that may jeopardize workers’ ability to remain employed.

Application:

More effective assault prevention would protect and support the workforce needed to care for our increasing elderly and disabled population.

Keywords: depression, epidemiology, health care, multi-site pain, musculoskeletal, sleep, work ability, workplace violence

INTRODUCTION

Preventive measures to improve workplace safety are widely recognized as important in developed countries, with one notable exception: workplace violence. Despite lively public debate, guidelines, and recommendations, violence at work keeps increasing while attention remains fixed on individuals’ behaviors. In Finland, workplace violence leading to physical injuries among female workers increased fourfold from 1980 to 2003 (Heiskanen, 2007). The number of fatal workplace violence incidents in the U.S. state of Washington was higher in 2009 than in the previous decade and more (Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, 2009). Workplace violence is especially common in health care; in the United States, the most frequently assaulted worker is a nursing home aide (Gates, 2004; Hall, Hall, & Chapman, 2009).

Part of the increase in reported workplace violence may be explained by growing awareness of the issue and employees’ and employers’ willingness to report incidents. On the other hand, changes in labor structure, mainly the growth of the service sector and perhaps also leaner staffing patterns, may have produced more opportunities for violence to occur. Other societal changes are that people have become more impatient and demanding, and the requirements for good service have risen (Heiskanen, 2007). If these increased expectations are not met, frustration and anger may be expressed verbally or physically by clients, customers, or members of the public.

Research on health consequences of nonfatal violent incidents has mainly focused on psychological distress (Eriksen, Tambs, & Knardahl, 2006). Physical fatigue, sleep problems, and headache are the most often reported somatic symptoms (Crofford, 2007; Hogh, Borg, & Mikkelsen, 2003). Musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders, which are especially prevalent among health care workers, have rarely been considered as a consequence of workplace violence. In a previous cross-sectional study, we found a dose–response relationship between physical assaults at work and musculoskeletal pain among nursing home workers (Miranda et al., 2010). We also noted a lack of other literature on this topic. Given the magnitude of musculoskeletal disorders in the population, attention is due to any factor that contributes to risk, particularly prolonged or more severe symptoms and resulting work disability.

This prospective study therefore sought to assess frequency of workplace violence over 2 years among nursing home workers and to investigate the causal role of long-term exposure to violence in a variety of musculoskeletal pain outcomes measured in three consecutive surveys.

METHOD

Study Population and Study Design

This study is based within an ongoing research initiative examining the effectiveness of occupational safety and health and workplace health promotion interventions in the long-term care sector (Promoting Mental and Physical Health of Caregivers through Transdisciplinary Intervention, within the Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace). The baseline study population consisted of all permanent full- and part-time clinical employees in 12 nursing homes within a single company, located in Maryland and Maine, USA. Employees of temporary agencies were not eligible to participate in the study. For the current report, office, laundry, food service, and janitorial staff were excluded.

The self-administered questionnaire was distributed and collected by the members of the study team at baseline in 2006 and 2007, prior to initiation of a safe resident handling (SRH) program. The follow-up questionnaires were similarly collected 12 and 24 months after baseline. For those workers who could not be met in person, such as third-shift and weekend employees, a prestamped, addressed return envelope was provided. Compensation of $20 was offered in exchange for each questionnaire that was completed and returned. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

The questionnaires collected information on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, length of education, ethnic origin), physical and psychosocial working conditions, current and recent health endpoints, health attitudes, and health behaviors. The two follow-up questionnaires also included questions on the SRH program. Most questions were based on previously published and validated items and scales. The survey questionnaire and code book are available from the authors upon request.

Musculoskeletal Symptoms

The six outcomes studied were (a) self-reported musculoskeletal pain in any of four specified body areas, (b) widespread pain, (c) pain intensity, pain interfering with (d) work or (e) sleep, and (f) pain co-occurring with depressive symptoms. All outcomes were measured at baseline and at 12 and 24 months.

Workers were asked whether they had experienced pain or aching during the preceding three months (Outcome 1: 1 = yes, 0 = no) in the lower back, shoulders, wrists or hands, and knees, all illustrated on a body map diagram. The number of body areas with pain was summed (score range = 0–4). Those with a sum of 3 or 4 were categorized as having “widespread pain” (Outcome 2: reference category: 0–2 pain areas). In addition, severity of pain in each region was assessed with a 5-point scale from no pain to extreme pain. Those who had reported moderate, severe, or extreme pain in any of the three areas were classified as having intense pain and were compared to those with no pain or mild pain (Outcome 3).

Pain interference with work was assessed with the question, “During the past week, were you limited in your work or other regular daily activities as a result of any (arm, shoulder or hand/back or knee) problem?” The five response options were not at all, slightly limited, moderately limited, very limited, and unable to work or do other regular activities (Outcome 4). Pain interference with sleep was assessed with the question, “During the past week, how much difficulty have you had sleeping because of any (arm, shoulder or hand/back or knee) problem?” The five response options were no difficulty, mild difficulty, moderate difficulty, severe difficulty, and so much difficulty that I can’t sleep (Outcome 5). A question about depressed feelings (“During the past 4 weeks, have you felt downhearted and depressed?”) had five response categories, from none of the time to all of the time. The having intense pain and feeling depressed most or all of the time were combined and compared to those with only one or neither (Outcome 6).

Working Conditions

Information about physical assaults at baseline and at 12- and 24-month follow-up was elicited with the question, “In the past 3 months, have you been hit, kicked, grabbed, shoved, pushed or scratched by a patient, patient’s visitor or family member while you were at work?” The response categories were no, not at all; 1 time; 2 times; 3 times; and more than 3 times. After reviewing the response distribution, a three-level variable was formed: 0 = no, 1 = 1–2 times, 2 = 3 or more times for each measurement occasion. Four cumulative exposure groups were also formed, describing exposure to violence over the 2-year follow-up as 1 = none (no recent assault reported at any measurement point), 2 = occasional (any assault at one measurement point out of three), 3 = frequent (two measurement points out of three), and 4 = persistent (all three measurement points).

Other work environment characteristics were treated as potential confounders based on our prior analyses (Miranda, Punnett, Gore, & Boyer, 2011): psychological job demands, job control, and supervisor support (from the Job Content Questionnaire; JCQ; Karasek et al., 1998); physically demanding work (sum index of three physical exposures from JCQ: moving or lifting heavy loads, rapid and continuous physical activity, and awkward postures); and work–family interference (sum index of three items; Gutek, Searle, & Klepa, 1991).

Data Analysis

The prevalence of each musculoskeletal outcome at baseline and 1- and 2-year follow-ups was compared by number of baseline incident reports and by frequency of assault (no, occasional, frequent, or persistent) over the follow-up period. The latter tabulation by frequency of assault was also done after restricting to respondents whose job title was nursing aide in all three surveys. The risks of all six outcomes were then adjusted for all 10 potential confounders and estimated as prevalence ratios (PRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from log-binomial regression modeling, using the COPY method (Deddens & Petersen, 2008). All statistical analyses were carried out with the SAS software package (Version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The baseline survey was returned by 867 nursing home staff members who were direct providers of clinical care. Of these, 344 provided a full set of three questionnaires (baseline and 1- and 2-year follow-ups) and were thus designated as the fixed cohort for the present analyses. At baseline, 55% of them worked as nursing aides (CNA), 16% as certified medicine aides (CMAs), 15% as licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and 14% as registered nurses (RNs). Most (85%) of these individuals remained in the same job title during the 2-year follow-up period.

The baseline survey response was 72% of all eligible clinical staff listed on the workforce rosters (unweighted average of all 12 centers). We were unable to obtain an exact count of the eligible employees who were at work during the days the study team was on site, but from available estimates it appeared that about 90% of those individuals returned questionnaires. The corresponding average response rates for the 1-year and 2-year follow-ups were 75% and 73% of employees on payroll, respectively.

The distributions of baseline variables (pain outcomes, assaults, demographic factors, and other covariates) for the 344 participants in all three surveys were essentially similar to those for the baseline participants who missed one or two follow-up surveys (Table 1). The only exceptions were that those who responded to all three surveys were slightly older and had more education than those lost to follow-up. Of the 344 respondents with three surveys, 266 had no missing values for any of the variables used in the regression models.

TABLE 1:

Baseline Characteristics of the 344 Participants With Three Surveys (Baseline, 1- and 2-Year Follow-Ups) Compared to Workers Excluded From Analysis Due to Incomplete Follow-Up (Missing Either or Both 1- or 2-Year Surveys)

| Study Respondents With 3 Surveys (Included): n = 344a | Baseline Respondents Without 3 Surveys (Excluded): n = 523a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Musculoskeletal outcomes | ||||

| Pain at any site | 248 | 72 | 385 | 74 |

| Widespread pain | 63 | 18 | 71 | 14 |

| Intense pain | 181 | 54 | 282 | 55 |

| Pain interferes work | 117 | 35 | 193 | 37 |

| Pain interferes sleep | 137 | 41 | 215 | 42 |

| Intense pain plus feelings of depression | 67 | 20 | 113 | 22 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 314 | 94 | 460 | 90 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <40 | 121 | 37 | 248 | 50 |

| 40+ | 208 | 63 | 252 | 50 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 147 | 43 | 219 | 42 |

| African American | 158 | 46 | 254 | 49 |

| Other | 39 | 11 | 50 | 10 |

| Education (years) | ||||

| 1–7 | 57 | 17 | 125 | 24 |

| 8–9 | 100 | 30 | 179 | 35 |

| >9 | 182 | 53 | 208 | 41 |

| Nursing aide | 243 | 71 | 341 | 65 |

| No. of physical assaults in past 3 months | ||||

| 0 | 150 | 45 | 271 | 54 |

| 1–2 | 91 | 27 | 131 | 26 |

| 3+ | 91 | 28 | 104 | 21 |

| Likely to leave the job in 2 years | 127 | 38 | 222 | 44 |

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Physical demands of work (range = 4–16) | 10.3 | 2.9 | 10.2 | 2.9 |

| Psychological demands of work (range = 2–8) | 5.9 | 1.2 | 5.8 | 1.2 |

| Job control (range = 4–16) | 5.5 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 1.4 |

| Supervisor support (range = 2–8) | 5.5 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 1.6 |

| Work-family imbalance (range = 1–4) | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| Safety climate at work (range = 1–4) | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.5 |

Some percentages may not sum to 100% due to missing values, which ranged from 0 to 24 records across all variables and surveys.

At baseline, more than one half of the participants (55%) reported at least one physical assault in the previous 3 months (Table 1). One out of four respondents (25%) had experienced incidents in all three periods (“persistent” violence), representing 49% of those exposed at baseline. Among all CNAs, the prevalence of persistent violence was 34%.

As anticipated, the largest proportion of musculoskeletal symptoms involved the low back (34% in both follow-ups with moderate or more severe pain), whereas about 25% of respondents reported comparable pain in each of the other body regions. All six pain outcomes showed exposure-response trends with baseline frequency of recent physical assault (Table 2): The more assaults reported at baseline, the more often were reports of any pain, widespread pain, and intense pain in each survey. The prevalences remained consistently elevated over time: For example, among those workers with exposure to several physical assaults at baseline, 68% reported moderate to extreme pain intensity at baseline, 68% at 1-year follow-up, and 67% at 2-year follow-up. Similar patterns were found for pain interfering with work and sleep and for the co-occurrence of pain and depression symptoms.

TABLE 2:

Prevalence of Pain Outcomes at Baseline (BL) and 1-Year (1-yr) and 2-Year (2-yr) Follow-Ups, by Number of Recent Assaults at Baseline

| Pain Outcomes at Baseline and 1-Year and 2-Year Follow-Ups | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Exposure to Violence (No. of Physical Assaults) | Pain in Any Body Area, % | Widespread Pain, % | Pain Intensity Moderate to Extreme, % | Pain Interferes With Work, % | Pain Interferes With Sleep, % | Intensive Pain and Feeling Depressed, % | ||||||||||||

| BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | |

| 0 (n = 133–150) | 65 | 57 | 58 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 43 | 40 | 39 | 24 | 30 | 34 | 28 | 32 | 35 | 14 | 16 | 12 |

| 1–2 (n = 86–91) | 74 | 62 | 76 | 20 | 23 | 16 | 56 | 56 | 65 | 35 | 41 | 49 | 43 | 54 | 59 | 23 | 23 | 26 |

| 3 + (n = 87–91) | 85 | 84 | 80 | 35 | 31 | 22 | 68 | 68 | 67 | 53 | 48 | 47 | 60 | 57 | 56 | 28 | 26 | 29 |

Similarly, there was an increasing trend in pain outcomes with long-term frequency of exposure to violence (Table 3): The pain outcomes at each measurement point were least frequent among workers without any recent assault and highest among those exposed persistently over 2 years. When this analysis was restricted to only those who had worked as CNAs throughout the follow-up period, these results were very similar.

TABLE 3:

Prevalence of Pain Outcomes at Baseline (BL) and 1-Year (1-yr) and 2-Year (2-yr) Follow-Ups, by Number of Yearly Reports of Violence During Follow-Up

| Pain Outcomes at Baseline and 1-Year and 2-Year Follow-Ups | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Violence Over 2 Years | Pain in Any Body Area (%) | Widespread Pain (%) | Pain Intensity Moderate to Extreme (%) | Pain Interferes With Work (%) | Pain Interferes With Sleep (%) | Intensive Pain and Feeling Depressed (%) | ||||||||||||

| BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | BL | 1-yr | 2-yr | |

| None = 0 (n = 87–99) | 65 | 56 | 60 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 41 | 37 | 37 | 20 | 25 | 29 | 27 | 29 | 32 | 14 | 12 | 10 |

| Occasional = 1 (n = 53–57) | 68 | 63 | 56 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 54 | 44 | 41 | 35 | 32 | 39 | 39 | 35 | 44 | 17 | 24 | 20 |

| Frequent = 2 (n = 73–77) | 79 | 74 | 81 | 23 | 30 | 22 | 60 | 62 | 65 | 42 | 52 | 47 | 47 | 58 | 53 | 24 | 23 | 18 |

| Persistent = 3 (n = 84–87) | 80 | 74 | 82 | 29 | 28 | 16 | 64 | 67 | 72 | 48 | 46 | 53 | 52 | 58 | 64 | 28 | 25 | 36 |

Physical assaults at baseline increased the risk of all pain outcomes at 1-year follow-up after adjustment for all 10 covariates through multivariable regression modeling. The highest increase, a PR of 2.5, was found for widespread pain (Table 4). Further adjustment for baseline pain reduced the effects negligibly.

TABLE 4:

The Risk of Various Pain Outcomes at 1-Year Follow-Up, by Exposure to Violence (Number of Assaults) at Baseline

| Risk of Pain Outcomes at 1-Year Follow-Up | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Exposure to Violence (No. of Physical Assaults) | Pain in Any Body Area | Widespread Pain | Pain Intensity Moderate to Extreme | Pain Interferes With Work | Pain Interferes With Sleep | Intensive Pain and Feeling Depresseda | ||||||

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1–2 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.6 | 2.5 | 1.3–4.7 | 1.6 | 1.2–2.2 | 1.7 | 1.2–2.4 | 1.8 | 1.3–2.5 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.2 |

| 3+ | 1.4 | 1.2–1.8 | 2.4 | 1.3–4.4 | 1.6 | 1.2–2.1 | 1.6 | 1.1–2.3 | 1.8 | 1.2–2.6 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.0 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PR = prevalence ratio. Adjusted for age, gender, ethnic background, education, organizational unit, physical demands of work, psychological demands of work, job control, supervisor support, and work–family imbalance at baseline.

Reference group: no intensive pain or only pain or feeling depressed.

Persistent exposure to violence predicted pain at the 2-year follow-up for most outcomes (Table 5). Again, for widespread pain, the risks were higher by two- to threefold. Four outcomes showed a dose–response trend. Co-occurring feelings of pain and depression had a PR of 3.6 with persistent exposure, and even after adjustment for baseline pain the PR was 3.3 (95% CI = 1.5–7.0).

TABLE 5:

The Risk of Various Pain Outcomes at 2-Year Follow-Up, by Exposure to Violence During the 2 Years

| Risk of Pain Outcomes at 2-Year Follow-Up | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Exposure to Violence (Over the 2-Year Follow-Up) | Pain in Any Body Area | Widespread Pain | Pain Intensity Moderate to Extreme | Pain Interferes With Work | Pain Interferes With Sleep | Intensive Pain and Feeling Depresseda | ||||||

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Occasional | 0.9 | 0.6–1.3 | 2.8 | 1.2–6.7 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.8 | 1.3 | 0.8–2.1 | 1.6 | 1.0–2.5 | 2.1 | 0.9–5.1 |

| Frequent | 1.3 | 1.0–1.8 | 3.2 | 1.4–7.3 | 1.5 | 1.1–2.2 | 1.6 | 1.0–2.6 | 2.0 | 1.4–2.9 | 2.0 | 0.8–4.6 |

| Persistent | 1.3 | 1.0–1.8 | 2.0 | 0.8–5.0 | 1.7 | 1.2–2.4 | 2.0 | 1.3–3.1 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.0 | 3.6 | 1.7–7.6 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PR = prevalence ratio. Adjusted for age, gender, ethnic background, education, organizational unit, physical demands of work, psychological demands of work, job control, supervisor support, and work–family imbalance at baseline.

Reference group: no intensive pain or only pain or feeling depressed.

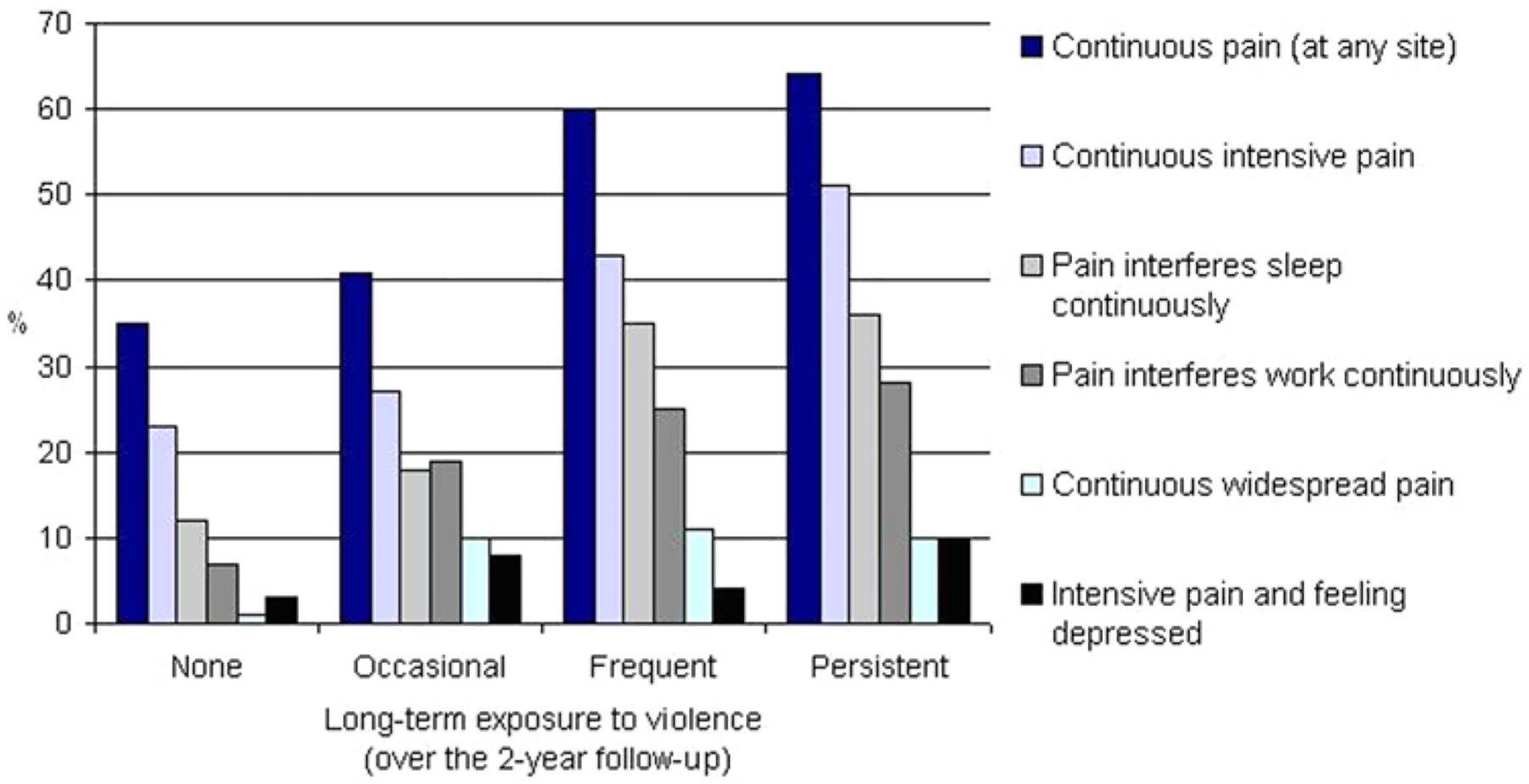

Workers with persistent violence over 2 years were twice as likely to report continuous pain symptoms (at all three measurement points) than those who had not been assaulted at all (Figure 1). Other pain outcomes that occurred continuously were also more common among those persistently exposed; the largest difference was seen for widespread pain (10% in persistent vs. 1% in nonexposed).

Figure 1.

The proportions of nursing home workers with continuous pain outcomes (at all three measurement points), by long-term exposure to violence at work.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of mostly female and middle-aged nursing home workers, assault by residents or their visitors was a common and persistent workplace hazard. One-third of CNAs reported at least one such recent incident on each of three consecutive surveys (“persistent exposure”). The effects of violence on musculoskeletal health were substantial. Of those workers who were physically assaulted frequently over the 2 years, musculoskeletal pain outcomes were 1.5 to 2.5 times more frequent than in those without such experiences. Most important, long-term exposure to violence was associated with an increase in the risks of all six pain-related outcomes after 2 years, even after adjustment for multiple individual and work-related physical and psychosocial covariates.

One half of the workers who had been exposed to at least one physical assault by a resident or resident’s visitor at the beginning of the study experienced further assault(s) over the next 2 years. This finding of high persistence of workplace violence is in line with results of earlier studies, although the number of prospective studies on this topic is very small. In a large random sample of the Danish working population, 50% of those workers exposed to violence reported still being exposed 5 years later. The risk of future violence was estimated to be 12 times higher among the previously exposed employees than among employees who had never been exposed (Hogh et al., 2003). In a study of nursing students, one third of those exposed to violence during the trainee period also reported violence 1 year after graduation (Hogh, Sharipova, & Borg, 2008). Persistent exposure may be more frequent among workers who provide direct care and who work more often in close contact with the patient/resident, such as CNAs and other health care assistants (Myers, Kriebel, Karasek, Punnett, & Wegman, 2006). The present report also showed that CNAs were slightly more often exposed to persistent violence than were other job groups, but the difference was relatively small.

Many reasons have been proposed for the high occurrence of workplace violence in health care institutions. One study among psychiatric hospital staff reported that those staff members who were assaulted recurrently were usually assaulted by the same patient, suggesting problematic relationships on either or both sides (Whittington & Wykes, 2006). In a single nursing home, the risk of an aide being assaulted was about doubled when working one’s usual floor and shift, after controlling for residents’ combativeness, further underscoring the possible role of familiarity between the individuals involved (Myers et al., 2006). Hogh and Viitasara (2005) suggested that a vicious circle may develop over time: A violent outburst from a patient may induce a stressful situation that changes the caretaker’s attitude and behavior toward the resident; the attacked staff person may reduce contact or begin to avoid the resident, or (the opposite) may become confrontational or aggressive in return, further increasing anger and aggression in the resident. Certainly it is possible that staff members’ and patients’ perceptions of these incidents are discordant (Harris & Varney, 1986). A recent large cross-sectional study among U.S. nurses and other nursing personnel suggested that the staff members’ history of childhood abuse and adult intimate partner violence should be considered as significant risk factors for experiencing violence at work (Campbell et al., 2011). The putative causal role of any these factors in the process, however, requires evidence from longitudinal studies. Regardless of the interpersonal dynamics in question, the current findings show that the effect for clinical employees is both physically and mentally deleterious.

Our previous cross-sectional study showed a dose–response association between exposure to violence and 3-month prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms (Miranda et al., 2011). This longitudinal study, with a wider variety of pain-related outcomes, confirmed these results. Most alarming is the new finding that assault had the strongest effect on those outcomes that affect the ability to continue working: widespread pain, pain interfering with work and sleep, and co-occurring pain and depressed feelings. All these pain-related features have been linked to work disability. Widespread pain has been shown to pose a considerable threat to self-assessed current work ability and to increase the risk of having a poor prognosis of future work ability (Miranda et al., 2010). Sleep problems relatively strongly predict early retirement due to disability, especially when the disability is related to musculoskeletal disorders (Salo et al., 2010). Moreover, in addition to the significant individual effects that pain and depression have on work disability, they reinforce each other; several authors have reported synergistic effects on self-assessed disability and work-loss days (Arnow et al., 2006; Buist-Bouwman, de Graaf, Vollebergh, & Ormel, 2005; Scott et al., 2009).

Most earlier workplace violence studies have been cross-sectional, so little is known of the long-term effects on workers’ health. A systematic review found five longitudinal studies as of 2003 in which the follow-up period was long enough to be able to measure late reactions (Hogh & Viitasara, 2005). These showed serious long-term consequences including a variety of cognitive, emotional, and psychosomatic symptoms, such as posttraumatic stress disorder. It is likely that these effects together negatively affect the workplace and work performance, mediated through workers’ motivation, efficiency and productivity, turnover, sickness absenteeism, and early disability pensions (Di Martino, 2003; Hoel, Sparks, & Cooper, 2001). All of these also represent economic burdens for employers.

Mechanisms for the Observed Associations

There are several mechanisms by which workplace violence might influence musculoskeletal pain, as we have previously discussed at length (Miranda et al., 2011). Some assaults cause direct injury, such as painful scratches and bruises, but it is unlikely that this alone would explain the strong associations found between violence and pain-related outcomes, especially widespread symptoms. Violence also has psychological effects. It may act via physical work patterns, that is, influencing changes in posture, movement, or other physical vectors. If a caretaker fears a violent outburst, she or he may try to keep a distance from the resident/patient, creating more awkward postures during patient care procedures or trying to lift the patient using techniques that increasingly load the trunk. Another hypothesis is that a physical assault, or even fear of a possible assault, generates anxiety. Elovainio and Sinervo (1997) tested these two hypotheses among Finnish elderly care workers. Their results supported the mediating role of psychological reactions such as nervousness and anxiety in the relationship of psychosocial stressors at workplace to musculoskeletal disorders. In a recent large prospective study among 4,000 Norwegian nurses’ aides, exposure to violence was among the strongest predictors of psychological stress 15 months later (Eriksen et al., 2006). In a Canadian study among home health care workers, the major reason for experiencing stress was workplace violence (Denton, Zeytinoglu, & Webb, 2000). Violence also increases the risk of future clinical psychiatric diagnosis of an anxiety and stress disorder (Wieclaw et al., 2006).

This stress-mediation hypothesis is also biologically plausible. Psychological stress is known to delay tissue healing, affect individual pain threshold and intensify pain experience, and worsen one’s ability to cope with pain. Cumulative stress has been associated with a number of physiological changes in the brain and body that indicate dysregulated hormonal and autonomic activity. Recent pain studies performed with brain imaging techniques have shown that the anticipation of pain, even before the actual painful event, causes activation in the pain-sensitive areas in the cortex of the brain (Wager et al., 2004). Unfortunately, detailed information about types of assaults was not obtained in the questionnaire, so we could not examine whether there were distinct patterns. Future studies should compare pain experiences (and pathways) among incident types and scenarios.

Methodological Strengths and Weaknesses of This Study

This study has both strengths and limitations. The longitudinal design with three annual surveys provided an opportunity to investigate changes in both exposure and outcomes over a 2-year period. The outcomes represent related but different features of musculoskeletal pain that are not usually assessed in parallel in the same study. The results were markedly consistent: Exposure to violence increased the likelihood of all outcomes. The response rate at baseline was relatively high, at least among those who were at work when the investigators were on site, and participants were very similar to the entire workforce in age, gender, race/ethnicity, and the proportions of clinical aides and nurses.

Although the study cohort with complete information from the three surveys was only one third of the baseline sample, baseline characteristics differed little between the cohort and those excluded for nonresponse to follow-up surveys or leaving employment during follow-up. The slightly higher participation among the older and more educated workers is consistent with other studies (Tolonen et al., 2006) but unlikely to affect these results markedly since neither age nor education was associated with the outcomes of this study. Thus we believe that there was no selection bias of major importance. We have previously shown that stated intention to leave in this workforce was associated with opportunities to participate in decision making, as well as social support and feeling respected at work (Zhang, Punnett, Gore, & CPH-NEW Research Team, 2012), but none of those factors was a predictor of the pain outcomes reported here.

Confounding also seems unlikely to have produced the associations reported here. The multivariable models were adjusted for multiple covariates. One workplace feature that we could not include was the number of residents cared for per day by each worker (Gates, 2004), as these data were not available from the employer and we did not think they could be estimated reliably by recall. On the other hand, we were able to include two other, more direct indicators of workload in the regression models.

The optimal prospective study design for studying the effects of workplace violence on pain depends both on the mechanism(s) of effect and the relevant induction time(s). A traditional “pain incidence” study would involve defining a cohort of workers free of pain at baseline and measuring the incidence of pain at a later time. This design would require knowledge of the likely length of time from assault to pain experience, which might be much shorter for pain from the direct injury than for pain mediated through anxiety about future assaults. Since these two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, repeated follow-up surveys at short intervals might be necessary to observe all of the consequent symptoms and describe the magnitude of the two processes. The 1-year follow-up intervals available in this study may not capture all musculoskeletal pain episodes or all assaults but are suitable for assessing the longer-term consequences of assault, whether from direct physical injury or its psychological effects.

Another commonly used design is to include both respondents with and without pain at baseline and then adjust for baseline pain status. This increases the available size of the cohort (especially in health care, where the prevalence of pain is so high), but it is also somewhat problematic. Prior pain is known to be the strongest predictor of future pain, and it may also be caused by the same exposure of interest at baseline. Consequently, adjustment for baseline pain would leave little power to determine the additional effects of baseline exposure on future pain (Glymour, Weuve, Berkman, Kawachi, & Robins, 2005). Therefore, our primary regression models were not adjusted for baseline pain. We did fit secondary models with such adjustment. As expected, the risk estimates mainly decreased, but the decrease was (surprisingly) small. This suggests either that the prevalent pain under study was attributable to multiple causes or that exposure status is highly time-varying, that is, that assault prior to baseline pain is not strongly associated with assault during the follow-up period. Both of these are plausible explanations.

Another possible weakness is that assault history was available only by self-report. Studies that use self-reported data exclusively may be susceptible to same-source or common-method bias, in which the tendency to report both higher exposure and more symptoms leads to overestimated risk estimates. To the extent that study respondents underreport certain behaviors, such as alcohol drinking, sexual activity, or even violent incidents, because of perceived social undesirability, a diminished association would result. This is one reason that registers or objective measures are often considered superior to self-reported data. With respect to workplace violence, this is not an available solution. Many violent incidents at work are not officially reported; hence, company records or compensation claims underestimate the true frequency of workplace assaults (Findorff, McGovern, Wall, & Gerberich, 2005; Taylor & Rew, 2011). Nor is it currently possible to measure pain in any way other than by asking the worker. Alternative outcomes, such as pain-related health care visits, hospitalizations, sickness absences, or medication use, require diagnosis-level information on specific clinical disorders and access to health registers. In this study, it was not possible to include any such register-based data.

Implications of These Findings

The problem of workforce sustainability in the long-term care sector is reaching critical levels. In the United States alone, 5.8 million people were 85 years or older in 2010. By 2030, their number will increase to 8.7 million, and by 2050 it is estimated to be 19 million (Vincent & Velkoff, 2010). For these elderly, as well as patients with long-lasting and disabling illnesses, long-term residential care is an essential service and among the most rapidly expanding in the United States as well as in many other industrialized countries. Health care or supportive care is also increasingly given in the homes of the patients and elderly people by health care professionals, and home care workers are also vulnerable to assault (Denton et al., 2000; Geiger-Brown, Muntaner, McPhaul, Lipscomb, & Trinkoff, 2007).

This prospective study provides new knowledge on the accumulation of workplace violence experienced by health care workers and its significant contribution to a variety of musculoskeletal pain outcomes. Workplace violence is a common and persistent hazard in nursing home work and, especially when occurring over the long term, is strongly associated with pain features that most jeopardize caregivers’ ability to continue working. To meet the increasing requirements of the aging and disabled population and to supply and preserve professional, committed, and healthy staff to care for these elderly, this major workplace hazard should be prevented. More important, the driving force for prevention should be the substantial affliction that workplace violence creates for workers in terms of deteriorated health and work ability.

Health care institutions need to state clearly and implement policies and practices to create safe environments (Forster, Petty, Schleiger, & Walters, 2005; Phillips, 2007). As shown by successes in addressing other types of workplace safety problems, violence prevention also requires substantial joint efforts by employees, occupational health and safety officials, government representatives, and other stakeholders, buttressed by national standards and/or legislation (Casteel et al., 2009; International Labour Office, 2002; Koné, Zurick, Patterson, & Peeples, 2012; Nachreiner et al., 2005).

KEY POINTS.

Clinical staff members in nursing homes are frequently physically assaulted by residents or their family members.

Being attacked at work predicted future musculoskeletal pain, including pain interfering with work and with sleep, and co-occurring pain and depression.

These outcomes are relevant to the high turnover of nurses and aides in the long-term care sector.

Employers, workers, and the public in general would benefit from more effective assault prevention initiatives to protect the workforce needed to care for our increasing elderly and disabled population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Samuel Agyem-Bediako, Jon Boyer, Nicole Champagne, Marian Flum, Gabriela Kernan, Alicia Kurowski, Suzanne Nobrega, Sandy Sun, Kyle Twarog, Cheryl West, Ameia Yen-Patton, and Susan Yuhas for assistance with data collection; Debbie LeBretton, Sandy Sun, and Kim Winchester for data scanning and cleaning; and Donna LaBombard and Deb Slack-Katz for liaising with facilities. This work was supported by Grant U19-OH008857 from the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH/CDC). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH.

Biographies

Helena Miranda is director of occupational health services of the OP Pohjola Group in Helsinki, Finland. She earned a doctor of medical science in medicine from the University of Helsinki, Finland, in 2003.

Laura Punnett is professor of epidemiology and ergonomics in the Department of Work Environment and co-director of the Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace, University of Massachusetts Lowell, USA. She earned a doctor of science degree in occupational health & epidemiology from the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

Rebecca J. Gore is senior statistician in the Department of Work Environment, University of Massachusetts Lowell. She earned her PhD in mathematics with an emphasis in applied statistics from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque in 1997.

REFERENCES

- Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, & Fireman B (2006). Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist-Bouwman MA, de Graaf R, Vollebergh WA, & Ormel J (2005). Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111, 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Messing JT, Kub J, Agnew J, Fitzgerald S, & Fowler B (2011). Workplace violence: Prevalence and risk factors in the Safe at Work study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteel C, Peek-Asa C, Nocera M, Smith JB, Blando J, Goldmacher S, … Harrison R (2009). Hospital employee assault rates before and after enactment of the California Hospital Safety and Security Act. Annals of Epidemiology, 19, 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofford LJ (2007). Violence, stress, and somatic syndromes. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8, 299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deddens JA, & Petersen MR (2008). Approaches for estimating prevalence ratios. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65, 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton M, Zeytinoglu I, & Webb S (2000). Work-related violence and the OHS of home health-care workers. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety, Australia and New Zealand, 16, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino V (2003). Workplace violence in the health sector: Relationship between work stress and workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Program on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/WVstresspaper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Elovainio M, & Sinervo T (1997). Psychosocial stressors at work, psychological stress and musculoskeletal symptoms in the care for the elderly. Work & Stress, 11, 351–361. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen W, Tambs K, & Knardahl S (2006). Work factors and psychological distress in nurses’ aides: A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 6, 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findorff MJ, McGovern PM, Wall MM, & Gerberich SG (2005). Reporting violence to a health care employer: A cross-sectional study. AAOHN Journal, 53, 399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster JA, Petty MT, Schleiger C, & Walters HC (2005). kNOw workplace violence: Developing programs for managing the risk of aggression in the health care setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 183, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DM (2004). The epidemic of violence against healthcare workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61, 649–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C, McPhaul K, Lipscomb J, & Trinkoff A (2007). Abuse and violence during home care work as predictor of worker depression. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 26, 59–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, & Robins JM (2005). When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162, 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutek BA, Searle S, & Klepa L (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work–family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 560–568. [Google Scholar]

- Hall RC, Hall RC, & Chapman MJ (2009). Nursing home violence: Occurrence, risks, and interventions. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging, 17, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GT, & Varney GW (1986). A ten-year study of assaults and assaulters on a maximum security psychiatric unit. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen M (2007). Violence at work in Finland: Trends, contents, and prevention. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 8, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel H, Sparks K, & Cooper CL (2001). The cost of violence/stress at work and the benefits of a violence/stress-free working environment (Commissioned by the International Labour Organization). Manchester, UK: University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_108532.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hogh A, Borg V, & Mikkelsen KL (2003). Work-related violence as a predictor of fatigue: A 5-year follow-up of the Danish work environment cohort study. Work & Stress, 17, 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hogh A, Sharipova M, & Borg V (2008). Incidence and recurrent work-related violence towards healthcare workers and subsequent health effects. A one-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36, 706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogh A, & Viitasara E (2005). A systematic review of longitudinal studies of nonfatal workplace violence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14, 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. (2002). Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Program on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_160908.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Karasek RA, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM, & Amick BC III. (1998). The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 322–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koné RG, Zurick E, Patterson S, & Peeples A (2012). Injury and violence prevention policy: Celebrating our successes, protecting our future. Journal of Safety Research, 43, 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda H, Kaila-Kangas L, Heliövaara M, Leino-Arjas P, Haukka E, & Liira J (2010). Musculoskeletal pain at multiple sites and its effects on work ability in a general working population. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 67, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda H, Punnett L, Gore R, & Boyer J (2011). Violence at the workplace increases the risk of musculoskeletal pain among nursing home workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 68, 52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers DJ, Kriebel D, Karasek R, Punnett L, & Wegman DH (2006). The social distribution of risk at work: Acute injuries and physical assaults among healthcare workers working in a long-term care facility. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachreiner NM, Gerberich SG, McGovern PM, Church TR, Hansen HE, Geisser MS, & Ryan AD (2005). Relation between policies and work related assault: Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62, 675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S (2007). Countering workplace aggression: An urban tertiary care institutional exemplar. Nursing Administrative Quarterly, 31, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo P, Oksanen T, Sivertsen B, Hall M, Pentti J, & Virtanen M (2010). Sleep disturbances as a predictor of cause-specific work disability and delayed return to work. Sleep, 33, 1323–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bromet E, Fayyad J, … Williams D (2009). Mental-physical co-morbidity and its relationship with disability: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 39, 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, & Rew L (2011). A systematic review of the literature: Workplace violence in the emergency department. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 1072–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolonen H, Helakorpi S, Talala K, Helasoja V, Martelin T, & Prättälä R (2006). 25-year trends and socio-demographic differences in response rates: Finnish Adult Health Behaviour Survey. European Journal of Epidemiology, 21, 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GK, & Velkoff VA (2010). The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050, population estimates and projections (Current Population Reports P25–1138). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, & Davidson RJ (2004). Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science, 303(5661), 1162–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Department of Labor & Industries. (2009). Fatality data summaries. Olympia: Author. Retrieved from http://www.lni.wa.gov/Safety/Research/FACE/DataSum/default.asp [Google Scholar]

- Whittington R, & Wykes T (2006). Violence in psychiatric hospitals: Are certain staff prone to being assaulted? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Burr H, Tüchsen F, & Bonde JP (2006). Work related violence and threats and the risk of depression and stress disorders. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 771–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Punnett L, & Gore R, & CPH-NEW Research Team. (2012). Relationships among employees’ working conditions, mental health, and intention to leave in nursing homes. Journal of Applied Gerontology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0733464812443085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]