Abstract

Background

Across the world, healthcare systems have become increasingly complex, making it more difficult for nurses to act ethically when faced with moral dilemmas. The COVID-19 pandemic in particular revealed ethical challenges, highlighting the need for nurses to attain high levels of moral competence. Nurses who attain moral competency provide superior patient care because they have integrated clinical competence with sensitivity to moral values. Understanding what comprises moral competence in nursing is crucial to stimulate and support consistent ethical behaviour. However, most studies to date on moral competence in nursing have been conducted at a national level and only from a particular stakeholders’ perspective, thereby limiting their utility.

Objective

To explore and document the characteristics of the morally competent nurse from the perspectives of nurses and patient representatives practicing in Europe.

Design

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted.

Methods

Semi-structured focus group discussions were conducted to collect data. Data were analysed with a descriptive thematic method.

Participants

A purposive sample of 38 nurses and 35 patient representatives was recruited. They were geographically spread across six European countries.

Results

The overarching characteristic of a morally competent nurse that emerged from our thematic analyses of group discussions is that they are person-centred. This person-centred quality is expressed on intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. The theme ‘main components of moral competence in nurses’ can be divided into three subthemes: knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Conclusions

This study provided a deeper understanding of moral competency in nurses, from both the perspective of nurses and patient representatives in Europe. Morally competent nurses are person-centred and possess the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes that foster positive relationships with patients and their families, as well as with their nursing colleagues. Pedagogically, the results should be useful for teaching how moral competence can be supported in practice and how nurses can be better prepared to deal with ethically sensitive care practices in constantly evolving healthcare systems.

Keywords: Ethics, Focus groups, Moral competence, Multinational perspectives, Nursing, Patient representatives, Qualitative research

What is already known?

-

•

Healthcare systems across the globe are becoming increasingly complex, and nurses are increasingly confronted with morally difficult situations.

-

•

To develop a meaningful curriculum that effectively teaches nurses moral competence, educators need a comprehensive understanding of what constitutes a morally competent nurse.

-

•

Previous studies are lacking in which nurses’ moral competence is investigated from a multi-stakeholder and international perspective.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

What this paper adds?

-

•

A comprehensive view of what characterises moral competence in nursing from both the perspectives of European nurses and patient representatives.

-

•

Nurses and patient representatives see morally competent nurses as person-centred and possessing the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to build strong relationships with patients and their families, and with colleagues in the multidisciplinary team.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Current healthcare systems are complex entities where several factors contribute to complexity. These factors include increased life expectancy of patients and associated chronic illnesses, technological progress in diagnostics and care delivery, fragmentation of services, diminishing public trust in healthcare professionals, and shrinking budgets (Braithwaite et al., 2017). Thus, nurses are confronted with an increasing number of morally challenging situations that requires them to make difficult ethical decisions. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example in which nurses faced ethical issues requiring high levels of moral competence (Oh and Gastmans, 2024; Peter et al., 2022). Apart from knowledge of general ethical principles and ethics codes, nurses rarely receive systematic ethical training, leaving them unprepared to face complex ethical issues (Papastavrou et al., 2024; Snelling and Gallagher, 2024).

Competent nurses significantly enhance patient safety, as prioritising clinical competence promotes delivery of high-quality care. Furthermore, in nursing care practices, the integration of professional knowledge with a sensitivity to moral values positively influences ethical decision-making. Besides underpinning nursing competency, this kind of integration emphasises the importance of upholding moral standards alongside clinical-technical competence (Goethals et al., 2010).

The recognition of the significance of ethics in healthcare, alongside the necessity for nurses to possess moral competence, is well-documented in the literature. For instance, there is an abundance of literature highlighting the nurse as a moral agent (Arries, 2005; Holland, 2010; Vanlaere and Burggraeve, 2024). However, it is imperative to understand what it means to be morally competent and to effectively cultivate moral competence in nursing care practices (Kulju et al., 2016; Koskenvuori et al., 2018). Studies indicate that moral competence in nurses is multifaceted, encompassing ethical knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable individuals to engage in ethical behaviour (Goethals et al., 2010; Kulju et al., 2016; Koskenvuori et al., 2018). While research exploring factors contributing to the moral competence of nurses remains somewhat limited, there is growing interest in this area (Wiisak et al., 2024). Moreover, studies reveal that moral competence in nursing is responsive to factors at multiple levels, from individual nurses to societal influences (Wiisak et al., 2024).

In addition to research on the meaning and the components comprising nurses’ moral competence, numerous studies have explored perspectives of a variety of stakeholders on moral competence in nursing. However, most of these studies have been conducted at a national level and from a particular stakeholders’ perspective, for example, nurses (Choe et al., 2022; Hemberg and Hemberg, 2020); nurse leaders (Barkhordari-Sharifabad et al., 2018); patients with oncological issues (Rchaidia et al., 2009); older adults and long-term facility residents (Van der Elst et al., 2012). Hence, the aim of this study was to identify and document the perspectives of European nurses and patient representatives on what characteristics define the morally competent nurse.

The study has been initiated by the PROMOCON consortium (www.promocon.upatras.gr/en/), a collaboration of nursing ethics researchers from six countries (Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Ireland, and Italy). The project aims to develop a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) and a best practice guide to meet the need for innovative learning and teaching practices in the field of nursing ethics. To reach this aim, the consortium deemed it necessary first to obtain an international perspective on moral competence in nursing, incorporating insights from both nurses and patient representatives. In this article, the terms ‘moral’ (mainly referring to individual, personal values and principles) and ‘ethical’ (mainly referring to theoretical reflection on values and principles) will be used interchangeably as is common in the academic literature on ethics.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study used a descriptive qualitative research design. Data were collected using in-person focus group discussions with nurses and patient representatives (Krueger and Casey, 2014). The use of focus groups provided a relaxed environment for participants to discuss stakeholder perspectives on this poorly understood topic (Dil et al., 2024). Thus, this design format could generate richly described data through participant interactions, self-disclosure, and elaboration of other group members’ responses (Papastavrou and Andreou, 2012). Focus group discussions also have a synergistic effect facilitating the expression of new ideas that may have been left undisclosed through individual interviews (Stalmeijer et al., 2014).

The Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007) was used to document the details of our methods and procedures (see Supplementary File 1).

2.2. Participants and setting

Using purposive sampling (Patton, 2015), we recruited participants between March and May 2023 from six European countries: Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Ireland and Italy. In each country, two types of focus groups were conducted: one comprising only nurses and one comprising only patient representatives. To recruit nurses, researchers in each country contacted nurses working in different healthcare settings and/or educational departments; we aimed to recruit nurse participants with different educational backgrounds. To recruit patient representatives, the same researchers in each country contacted people from different patient associations and representatives of patients. To ensure a variety of perspectives, a heterogeneous sample using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria was established (Table 1). Each focus group in each partner country needed to have four to nine participants (Krueger and Casey, 2014).

Table 1.

Selection criteria for focus group participants.

| Inclusion criteria – nurse participants | Exclusion criteria – nurse participants |

|---|---|

| Professional nurses, nursing educators, or nursing students (e.g., bachelor, master, doctoral level) | Nurse aids, nurse assistants, or similar working capacity |

| Active in their professional or student role | Not active in their professional or student role |

| Inclusion criteria - patient representatives | Exclusion criteria - patient representatives |

| Representatives of patients (including active members of patient associations, sensitive to the needs of patients, patient advocates) | In-patients currently being cared for in healthcare institutions, or similar patient status |

First contact with potentially interested participants was made by phone or email. During that initial contact of candidate participants, we provided a participant information brochure which provided information so that participants could make an informed decision about taking part in the focus group. If candidates were interested in participating, they were asked to fill in the socio-demographic questionnaire and return it to the researchers so that a suitable time and date for the focus group could be arranged.

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected according to a pre-defined data-collection protocol that was designed by the researchers (see Supplementary File 2). All focus group discussions were semi-structured and were conducted in-person between April and June 2023. The focus groups were led by two local academic researchers (one moderator and one observer) from each country. The discussions were conducted in the participants’ native language. The discussion guide was designed by the Finnish research team (RS, JW, MS) based on previous research (Koskenvuori et al., 2019; Kulju et al., 2016). The final version of the discussion guide was piloted in Italy (AP, SC, AG) and no changes were suggested (see Supplementary File 2).

Each focus group began with an introduction round, where the moderator, the observer, and the participants briefly introduced themselves (name, current position, and background). Next, the participants were given the opportunity to ask questions. All focus group discussions lasted approximately two hours.

With the participants’ permission, all focus group discussions were audio-recorded using a digital recorder. During the focus group discussions, notes were taken to help the researchers identify which quotes belonged to which participants during the transcription of audio-recordings.

2.4. Data analysis

Data obtained through the focus group discussions were analysed using descriptive qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Audio recordings were first transcribed verbatim. In each country, two researchers conducted a preliminary analysis of the transcribed data, allowing them to verify that provisional themes being considered were not drifting away towards themes irrelevant to our study aims and that the analysis was consistent with the descriptive nature of the research (Doyle et al., 2020).

The preliminarily analysis involved repeatedly reading the transcripts, identifying codes, collapsing them, and developing initial themes. Frequent meetings were held with all the analysts in each country to discuss candidate themes being developed and to ensure that analyses were being done consistently across the study countries. From these discussions, two central thematic foci emerged: (1) General characterisations of the morally competent nurse, and (2) main components of moral competence in nurses.

Data from the focus groups of nurses and data from the focus groups of patient representatives were analysed separately using identical procedures. Once the initial themes had been developed, all themes and quotes characterising those themes were translated into English by the researchers who conducted the interviews. A subgroup of researcher-analysts was then convened. Representatives from each country comprised these subgroups and finalised the themes. Their aim was to examine the initial themes identified in transcripts from each country, to collapse similar themes into a single theme, and to develop the final corpus of themes, subthemes and defining aspects of these subthemes. There was a significant overlap of the themes identified in the nurse focus groups and those from the patient representative groups. Hence, we decided to merge these themes into one set of themes, which are presented here and exemplified using verbatim quotes from the transcripts.

Several processes ensured trustworthiness of the analysis. This included use of a standardised data collection protocol; frequent meetings with the research teams at national and international levels (e.g., to clarify the meaning of terminology in the different languages); deciding which areas to focus our analyses on; and consistent use of Braun and Clarke's (2021) thematic analysis framework. Following a rigorous analytic process, thematic saturation (Rahimi and Khatooni, 2024) was achieved by consensus among the subgroup analysts.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Prior to conducting the focus groups, approval was obtained from the National Bioethics Committee of Cyprus (Ref. No. 2023.01.82); the University of Udine Institutional Review Board, Italy (Ref. No. 33/2023); the Ethics Committee of the Department of Nursing, University of Patras, Greece (Ref. No. 29,974); and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences in Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland (Ref. No. 230,501). The study was not subject to the relevant Belgian and Finnish legislation. Therefore, no additional approval from Belgian or Finnish ethics committees was necessary.

All participants voluntarily took part in the study. They were informed in advance about the purpose and nature of the focus group discussions, and their rights to withdraw at any time. They all signed an informed consent document. The results of this study are reported in an anonymised manner so that no participant can be identified.

3. Results

3.1. Description of study sample

The final group of participants consisted of 38 nurses and 35 patient representatives. The majority were women, and they lived in geographically diverse areas in the six study countries (see Table 2, Table 3). The age of the nurses ranged from 20 to 49 years old, whereas the age of the patient representatives ranged from 30 to 59 years old. All the nurses, except participants who were nursing students, had at least a bachelor's degree. More than half of them had an additional qualification in a nursing discipline or other field (e.g., bioethics). Most of the patient representatives also had at least a bachelor's degree, and they worked in patient advocacy organisations that dealt with a variety of health conditions.

Table 2.

Participant demographics stratified by focus group: nurses (N = 38).

| Focus group ID | BE | CY | FI | GR | IR | IT | Total | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 38 | (100) | |

| Gender | Male | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 12 | (31.6) |

| Female | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 26 | (68.4) | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | (26.3) |

| 30–39 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 | (34.2) | |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | (10.5) | |

| 50–59 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | (21.1) | |

| 60–69 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | (7.9) | |

| Highest nursing education | Nursing student | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) |

| Registered nurse (bachelor level) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 21 | (55.3) | |

| Registered nurse (master level) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 13 | (34.2) | |

| Doctoral level | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Additional professional nursing qualification | No | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 16 | (42.1) |

| Yes | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 22 | (57.9) | |

| Community nursing | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | (10.5) | |

| Bioethics | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | (7.9) | |

| Mental health nursing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | (7.9) | |

| Geriatric nursing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Intensive care | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Palliative care leadership | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Physical activities science | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Hemodialysis and organ transplantation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Healthcare management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Information technology | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Midwifery | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Ophthalmology specialisation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (2.6) | |

| Years of nursing experience | 0–9 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 20 | (52.6) |

| 10–19 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | (26.3) | |

| 20–29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| 30–39 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | (15.8) | |

| Current working position | Clinical/bedside nurse | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 24 | (63.2) |

| Head nurse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Nursing educator/teacher | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | (21.1) | |

| Nursing researcher | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) | |

| Nursing student | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.3) |

Legend: ID, country identification; BE, Belgium; CY, Cyprus; FI, Finland; GR, Greece; IR, Ireland; IT, Italy.

Table 3.

Participant demographics stratified by focus group: patient representatives (N = 35).

| Focus group ID | BE | CY | FI | GR | IR | IT | Total | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 9 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 35 | (100) | |

| Gender | Male | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | (31.4) |

| Female | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 24 | (68.6) | |

| Age (years) | 20–29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | (8.6) |

| 30–39 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | (20.0) | |

| 40–49 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | (22.9) | |

| 50–59 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | (34.3) | |

| 60–69 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.7) | |

| 70–79 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | (8.6) | |

| Highest education level | Secondary school | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | (14.3) |

| Academic education (bachelor or master level) | 8 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 30 | (85.7) | |

| Focus of patient organisation | Patients' rights and bioethics | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | (22.9) |

| Elderly care | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | (17.1) | |

| Mental health | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | (11.4) | |

| Alzheimer's disease/dementia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | (8.6) | |

| Neurological disorders (e.g., ALS) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | (8.6) | |

| Cancer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | (8.6) | |

| Bone marrow donor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | (5.7) | |

| Palliative care | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | (5.7) | |

| Breast operated women | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (2.9) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (2.9) | |

| Heart disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (2.9) | |

| Infectious diseases | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (2.9) | |

| Role of participant in association | Chair | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 9 | (25.7) |

| Staff member | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 26 | (74.3) | |

| Experiences of hospitalisation as patient or as an informal caregiver | Yes | 8 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 30 | (85.7) |

| No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | (14.3) |

Legend: ID, country identification; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; BE, Belgium; CY, Cyprus; FI, Finland; GR, Greece; IR, Ireland; IT, Italy.

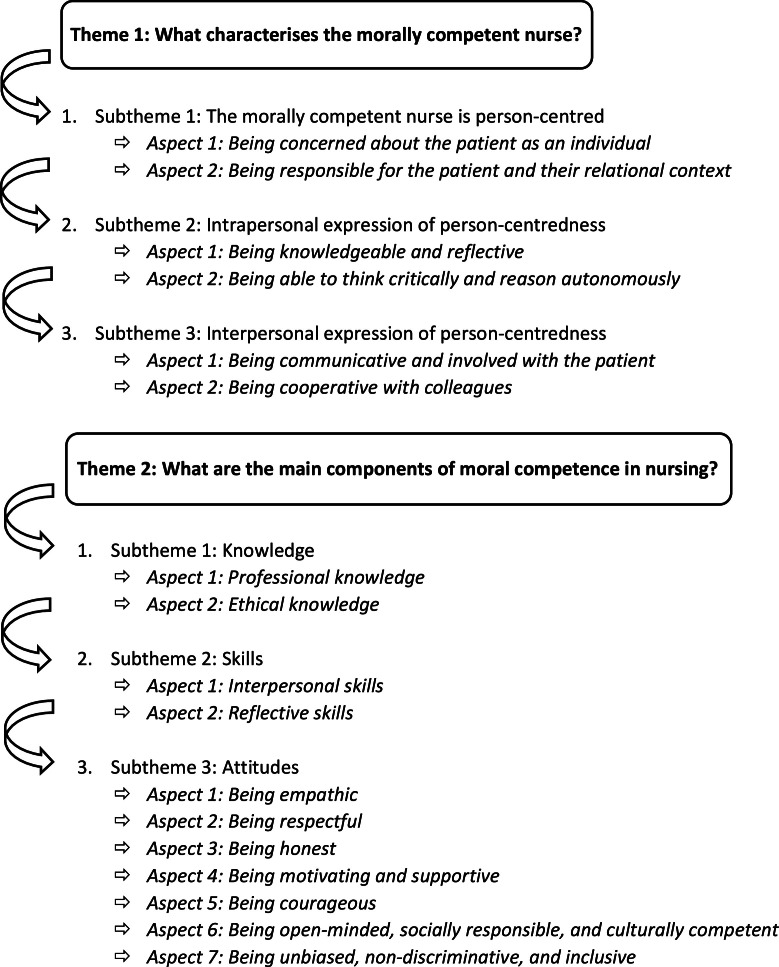

Our analysis identified two themes or broad areas of discussion in the focus groups. These themes enabled us to structure the perspectives of nurses and patient representatives on what defines the morally competent nurse. These themes can be expressed as the following questions: (1) What characterises the morally competent nurse? (2) What are the main components of moral competence in nursing? Fig. 1 presents the themes, subthemes, and defining aspects of those subthemes. This figure also serves as a template for the narrative presentation that follows.

Fig. 1.

The morally competent nurse as perceived by nurses and patient representatives.

3.2. Theme 1: what characterises the morally competent nurse?

Both groups of participants agreed that the overarching characteristic of the morally competent nurse is that they are person-centred. That is, the nurse inserts themselves in the patient's world. Participants said that person-centredness is expressed on both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. Table 4 presents representative quotes that illustrate these qualities.

Table 4.

Subthemes, aspects, and representative quotes regarding theme 1: ‘What characterizes the morally competent nurse?’.

| Subthemes | Aspects | Representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme 1: The morally competent nurse is person-centred | Aspect 1: Being concerned about the patient as person |

“Regardless of what branch of nursing you are working in, you should be working in a manner that is patient centred. The person is at the centre of everything you do.” (nurses, Ireland) “So, respecting the person, and how can you do that? This can be done in many ways, but communication is certainly a very important element or tool in this, because if you do not know what the values of that person are, then you cannot respond to them, and you cannot know what is important to them.” (patient representatives, Belgium) "So, professionally I think that the nurse must have competence and this is a basic prerequisite and then he/she is that professional figure who must, has the duty to identify people's needs and to find and understand what the person's latent and residual resources are, to bring him/her to the maximum degree of autonomy in dealing with his/her illness […]” (patient representatives, Italy) |

| Aspect 2: Being responsible for the patient and their relational context | “As a nurse, it is important to literally see the family of the patient. When my husband was in the hospital, the nurse also said hello to me. He asked laughingly: "Ah are you the wife?", and […] "And are you okay at home?". So just, he had attention for my role too…” (patient representatives, Belgium) | |

| Subtheme 2: Intrapersonal expression of patient-centredness | Aspect 1: Being knowledgeable and reflective |

"To be able to act ethically, your values must be clear." (patient representatives, Finland) “I think it's also very important that you know yourself as a nurse. That you know:” I have these emotions, and when I get into a certain situation and I feel something is coming up in myself, that I'm first and foremost aware that these are my emotions and not the patient's or his family's".” (nurses, Belgium) “The competence within the individual also seems to me to be that you can go… to [be] reflective. So that you can put your own judgment between brackets, that you can look further, think further, further beyond the emotion.” (nurses, Belgium) “I think the real competence lies in making that transition to what the patient needs. […] But what I see a lot, is that people remain trapped in their own emotions. That they want to take care of the other person, but that the competence mainly consists of realizing: “This is not about me”, “I need to feel what the other person may need”.” (nurses, Belgium) “And above all, flexibility comes in again. I have to be flexible, I cannot be, in my opinion, too rigid in what is happening. […] I have to try to be fluid, for example to go, to move constantly, not to remain static because stillness does not then help in extracting oneself from certain situations.” (nurses, Italy) “The good thing is to find someone who is willing to discuss…yes, with you, to understand the choices, to talk about them together, why we behaved as we did, what we could have avoided, what to do. Not all environments are inclined to…this type of discussion.” (nurses, Italy) “Engaging with “What is my attitude and how does that reflect on my patient, on the people around me? What energy do I radiate? What is the impact of my actions, of my attitude?”.” (patient representatives, Belgium) “You need to be constantly aware of your own abilities. When in need, especially when it comes to scientific issues, you have to know your limits and ask for help” (nurses, Greece) “I think that the ethical reasoning happens after one has made a mistake. […] “Did I do well”, “Did I do wrong” probably starts in some way, so, this type of reasoning… The awareness of what happened, possibly being able to change my behaviour next time.” (nurses, Italy) |

| Aspect 2: Being able to think critically and reason autonomously |

“Someone who dares to do that, to stimulate that and who dares to break through or question things that seem obvious, such as routines, procedures, working methods, ideas about dealing with patients.” (nurses, Belgium) “Nurses saved the life of a patient for whom the physicians did not give any hope. They were thinking of ending his ICU treatment, but the nurses stood up for him and eventually his condition improved. They need to be decisive.” (nurses, Greece) “The patient is in the hospital and knows he is going to die. He has a cat and really wants to see that cat. The family smuggles in that pet in a box, and that is not allowed. I always find those situations exciting… That means so much to those patients, that you have actually deviated from all the rules… And that is actually tailored care, because those patients need that to be able to sleep, to be able to die…” (patient representatives, Belgium) |

|

| Subtheme 3: Interpersonal expression of patient-centredness | Aspect 1: Being communicative and involved with the patient |

“We have a large group of [ALS] patients who can no longer communicate themselves at a certain point, and what we very often notice with care providers/nurses is that people talk over the patient's head. And then there is only talk with the people standing around, and then it is exactly as if the patient has become a piece of furniture that is present because he himself can no longer communicate through speech, but probably they can in many other ways… At that moment that is completely overlooked, so I think… That focus, that 'patient centred' aspect, should never be overlooked in any circumstance.” (patient representatives, Belgium) “[…] there is the issue of non-judgmental listening, because the nurse has to listen to everything and try to actually understand what the patient is saying… […] this is definitely a moral aspect of behaviour, that is, I don't behave like a machine, like a performing machine, I have to ask myself what I'm doing and if everyone is also doing it in the right way, because it may be that even the physician hasn't understood, in the moment in which the patient said a certain thing.” (patient representatives, Italy) |

| Aspect 2: Being cooperative with colleagues |

“[…] It has happened to me many times to discuss about the same situation, two people see it in a different way: one person grasps the patient's anger, the other one the patient's fragility. They are two equal aspects of the same situation, but really perceived in a different way, so then your reaction is different.” (nurses, Italy) “[…] Maybe a person that…is excellent, without being full of oneself, but he/she should be an example for others and others should…take him/her as an example.” (nurses, Italy) |

3.2.1. Subtheme 1: the morally competent nurse is person-centred

In all the focus groups, the participants discussed what being person-centred means and how it is reflected in the day-to-day activities of the morally competent nurse. They said that person-centredness was manifested as producing tangible outcomes that are recognisable to the patient, their family, and the wider healthcare community. Thus, person-centredness had two aspects. The first aspect was being concerned about the patient as a person. The second aspect was being responsible for the patient and their relational context.

3.2.1.1. Aspect 1: being concerned about the patient as a person

Being person-centred meant that the morally competent nurse is concerned about the patient as a person, not as a case. This characteristic is founded on deeper-than-normal knowledge about the patient and on relationships centred around the patient's needs. Participants said that the morally competent nurse supports the patient: They help the patient to thrive, they help the patient to live with chronic illnesses, or they ‘stick’ to the patient to ensure a peaceful death. Participants shared that being person-centred is also about knowing when and how to tailor activities that promote the best interests of the patient and preserve their inherent dignity.

3.2.1.2. Aspect 2: being responsible for the patient and their relational context

Although participants emphasised the importance of putting the patient at the centre of care, this did not mean that they viewed the patient and their family and significant others separately as independent, disparate entities. On the contrary, the patient and their family are closely interconnected. While taking responsibility for the patient and their relational context could sometimes be a sensitive undertaking, the morally competent nurse acknowledges the patient-family dynamics, and as such, would also seek to understand, and respond to the family's needs. Thus, the nurse works to involve the family in patient care in a way that would promote positive health outcomes for the patient. Sometimes this required the nurse to spend more time with the family than clinically necessary, and even sacrifice their own time to do so.

3.2.2. Subtheme 2: intrapersonal expression of person-centredness

For the morally competent nurse, person-centredness is a characteristic that originates at the intrapersonal level. That is, it is a quality inherent to the nurse as an individual. Intrapersonal expression of person-centredness had two aspects: being knowledgeable and reflective, and being able to think critically and to reason autonomously.

3.2.2.1. Aspect 1: being knowledgeable and reflective

The focus group participants reported that being knowledgeable and reflective meant that the morally competent nurse is well-aware of their personal and professional values that inspire their nursing practice. Additionally, the nurse is sensitive to their own emotions and stressors and manages them effectively, putting them into proper perspective. However, the patient representatives pointed out that the morally competent nurse should reveal their own vulnerabilities, honestly telling their patients when they are experiencing difficulties as a nurse. In general, the participants agreed that the morally competent nurse should balance emotional and rational perspectives of their care practices to benefit the patient. Achieving this balance can be facilitated by examining one's own emotions and reflections in light of clinical observations, theoretical knowledge (e.g. legal regulations), and ethical frameworks.

Possessing moral competence, however, lies in applying intrapersonal and theoretical knowledge to support patient care. To be successful, participants agreed that the nurse must be able to continuously adapt their ways of thinking and behaviour to the current situation being experienced by the nurse and the patient. Having this kind of adaptability means that the well-being of the patient remains central to the care experience.

Within the context of being knowledgeable and reflective, participants said it is important for the morally competent nurse to reflect on both their own attitudes and actions and those of others. The morally competent nurse should be able to regularly arrange for situations to keep reflecting on their own behaviour, about what they are doing, individually and in a group. Participants said this ability to reflect on one's behaviour is imperative, especially when working under pressure in a difficult care environment or with staff shortages. Self-reflection also includes being aware of the impact one's behaviour might have on patients and relatives. One of the patient representatives said:

“It would be great if the nurses themselves could lie there for six hours and watch what happens, how the nurses talk, how the doctors talk, so they would understand what the patients hear.” (Patient representative, Finland)

The participants also emphasised that conducting this assessment of self and of colleagues regularly enables the morally competent nurse to detect possible blind spots—their own blind spots and those of others. The morally competent nurse continuously learns from their limits, even from errors. Doing so increases not only awareness, but also promotes a willingness to ask colleagues for help.

3.2.2.2. Aspect 2: being able to think critically and to reason autonomously

Participants said that the morally competent nurse also expresses person-centredness by developing the ability to evaluate situations critically and to reason autonomously. When providing person-centred care, nurses need to recognise the limitations of procedures and protocols, and to respond accordingly. This ability stems from knowing that patients as individuals do not fit neatly within ‘standardised’ categories, and that interventions sometimes require them to consider alternatives and courageouly move beyond traditional approaches to meet the patient's specific needs. Moreover, the morally competent nurse can explain clearly their reasoning for trying an alternative protocol.

Deviating from standard procedures and protocols and acting as a patient advocate in efforts to protect the rights and well-being of the patient are often related to the notion of ‘standing up to power’ and hierarchy, confronting authority, calling out injustices, and demanding change for the benefit of the patient. In considering the well-being of the patient, participants said that the morally competent nurse respectfully speaks up when they disagree and when they arrive at a different viewpoint about standard practices. A nurse gave the following example.

“Yes, it's more about ‘standing up for your patient's rights’. In oncology, patients sometimes tell you they no longer want chemotherapy. They say things like, ‘I've had a good life, and it's time for it to end.’ Then a doctor might persuade them to join a clinical trial, and the patient agrees. Later, the patient said to me: ‘I'm doing it more for the doctor than for myself.’ As a nurse, it's important to recognize when something isn't right and able to speak up. I will go to the doctor and tell him that the patient has shared a very different story with me.” (Nurse, Belgium)

Patient representatives illustrated critical-thinking ability of the morally competent nurse by linking this ability with the nurse providing ‘tailored care’. The morally competent nurse is capable of providing care based on the patient's specific needs as a unique person. This kind of ‘tailored care’ contrasts with that of standard care or care based solely on protocols, routines or theoretical frameworks. However, the morally competent nurse does not just provide anything that the patient asks for, but instead tries to understand the underlying reason for the request and adjusts the care process accordingly. While individualising the care offered, the morally competent nurse demonstrates not only the capacity to rationally depart from standardised approaches, but also shows the capacity to know when and how far they should deviate from them.

3.2.3. Subtheme 3: interpersonal expression of person-centredness

In contrast to intrapersonal person-centredness, person-centredness expressed interpersonally focuses on nurses’ moral competence strictly in relation to the patient and their relational context. At this level, participants considered two aspects to be important: being communicative and involved with the patient, and being cooperative with colleagues.

3.2.3.1. Aspect 1: being communicative and involved with the patient

Nurses who are involved with the patient are constantly responding to the communication needs of the patient. They send up ‘feelers’ to detect important information the patient is trying to transmit. In the focus groups with patient representatives, some participants talked about nurses using intuitive knowledge to ‘read’ their patient and discern needs that may not be expressed explicitly. In other words, the morally competent nurse is hypersensitive to meaning behind patient expressions. Then, nurses can translate these expressions into a clearer understanding of what the patient needs, provide tailored-care, and enter into a close relationship with the patient. The morally competent nurse is aware of communication challenges and finds ways to circumvent roadblocks to communication, to ‘converse’, in a sense, with patients who can no longer communicate verbally. For example, the nurse tries to find alternative ways to communicate, such as through sign language.

3.2.3.2. Aspect 2: being cooperative with colleagues

Interpersonal expression of person-centredness goes beyond the relationship between the nurse and patient. The morally competent nurse tries to cooperate with other team members for the benefit of the patient. A key facet of colleague cooperation is clear communication. To do so requires the nurse to cultivate relationships based on mutual trust. Within these relationships, robust discussions can take place, which at times, may lead to difficult exchanges that challenge traditional power relationships. In this context, the morally competent nurse shows leadership and inspires others, confident in their ability to serve as role models for other nurses and healthcare professionals.

3.3. Theme 2: what are the main components of moral competence in nursing?

Three subthemes or ‘components’ emerged from the theme ‘What are the main components of moral competence in nurses’: knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Fig. 1). Data suggested that both focus groups had a shared understanding of this theme. However, they spoke about it in slightly different ways, using different examples to highlight the importance of its three subthemes. Table 5 reports representative quotes.

Table 5.

Subthemes, aspects, and representative quotes regarding theme 2: ‘What are the main components of moral competence in nurses?’.

| Subthemes | Aspects | Representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme 1: Knowledge | Aspect 1: Professional knowledge |

“Increased knowledge about nursing in general, broader understanding of the basic nursing activities, and then especially about ethical actions, that they are not just words but what they really mean … could say what you don't know or what you can't justify.” (nurses, Finland) “And then I would do a bit of general and dynamic psychology here, to have a general background, also to understand how certain people could behave out of the ordinary let's say, that is, you, as nurse, you get schizophrenic people, you have to educate them, you have to pick up on signals.” (patient representatives, Italy) “Knowledge about basic rights, basic legislation, the rights, status and rights of the client and the patient should be the cornerstone." (patient representatives, Finland) “Knowing the facts, and then you can also encourage the patient to say “You have the right to refuse treatment”. That's patient law. And also: “Do you know the consequences of participating in the study? […] So yes, pointing this out to the patient.” (patient representatives, Belgium) “We have so many foreigners who come to our country and happen to get sick and need to be treated in our hospitals. Based on their own culture something that is moral for us is immoral for them.” (nurses, Cyprus) |

| Aspect 2: Ethical knowledge |

“Knowledge about care, what that entails, what values are guiding… what does self-determination mean really… what does it mean in the care of an adult patient that they are also in charge of their own health and care or their own affairs… so they are capable… but in practice also the responsibility if he/she is not able to decide about his/her care…” (nurses, Finland) “I think you should have a basic knowledge of… Yes, 'values and norms' are always so quickly mentioned in one denominator, but if you ask to name them, then it is like “Oh, I don't know them…”. When I went to nursing school, I thought it was very helpful to learn how to deal with it practically, and then how to put it against the rights of the patient. I think nurses should learn that through very simple exercises.” (patient representatives, Belgium) “Ethical theories are important, but it depends on how it is taught, because it shouldn't be terms students just memorize for the exam, but they should be able to play with terms so they can work around with it.” (nurses, Belgium) |

|

| Subtheme 2: Skills | Aspect 1: Interpersonal skills |

“In relation to communication…I believe from a moral point of view that it encourages patients to feel safe and trusting towards me and open up more about information related to other different problems that he might not have shared with us in other circumstances.” (nurses, Cyprus) “We once had a palliative reference nurse who even went to the people of the cleaning team to ask about their opinion. Those cleaning people came into the room of the patient every day, they saw the families… And they also picked up on things that bothered those families, that were not always said directly to the doctors or nurses… So, I think it is important to hear different layers.” (nurses, Belgium) “…I think it would help to develop the ability to discuss these ethical cases in a team, which is what all nurses will have to do, since we work in teams.” (nurses, Italy) “It is important to walk in the patient's shoes, you cannot help them if you don't get a deeper understanding of their problems.” (nurses, Greece) |

| Aspect 2: Reflective skills |

“At least while the nurse decides, he/she should recognize moral dilemmas and understand what was done, and critically reflecting the conflict situation between the options …. I mean to go through a moral dilemma…” (nurses, Cyprus) “Maybe knowledge affects ethical dilemmas, if there is a deficiency of knowledge on how to classify which incident is urgent, that is resulting in dilemmas.” (patient representatives, Cyprus) “Excellence in my opinion is in the optimisation of time, in the management of nursing care that is delivered perhaps every day to patients, but with a special consideration for ethics. And then excellence, in order to differentiate it from standard competence, must necessarily be catalytic, it means that a nurse that is excellent, is a nurse that inspires his/her colleagues and who also acts as a reference to patients. And this is done not necessarily during his extra time… […].” (nurses, Italy) |

|

| Subtheme 3: Attitudes | Aspect 1: Being empathic | “I'm thinking about the attitude of openness, I mean being inside the situations and to have an open ear and understand, let's say, what is told to him/her, and also the attitudes and behaviours of the patients, of the caregivers. […] Sometimes we have to “endure hardships” as health nurses because there may be difficult situations, so the fact of being able to stay in very complex situations, to stay there, to be open, to actively listen…it's not easy at all.” (nurses, Italy) |

| Aspect 2: Being respectful |

“An 80-year-old man and you take him naked on the trolley to pass him through all the corridors because you have to take him for an examination, this is a violation of his dignity… this is not ethical.” (patient representatives, Cyprus) “Being respectful to the person is very important to me. Even if that person can't make many choices at that moment. If you look at palliative patients, I still leave them the choice of which dress they want to wear today. I know it's just a limited choice, but you don't have many choices left when you are at the mercy of the bed…” (patient representatives, Belgium) “I have had an experience in the past…pneumonia…but what amazed me a lot was how the nurse pursued me. Even though I am on a wheelchair, the nurse didn't make me feel like a freak or a burden to her.” (patient representatives, Greece) |

|

| Aspect 3: Being honest |

"I was with a dying patient in intensive care who had suffered a massive brain haemorrhage and it was quite clear that he was going to die. […] And so, the relatives didn't understand the situation at all, they must have been so shocked that they didn't understand the situation. Many times, the nurse had to tell them (relatives) in a very sensitive way what was going to happen […]." (patient representatives, Finland) "The doctor has spent two minutes explaining the facts and then the nurses have stayed and listened and explained and they have really, in my opinion, had the feeling that they answer every single question I asked and they haven't been in a hurry.” (patient representatives, Finland) |

|

| Aspect 4: Being motivating and supportive |

"[…] It's not just about what is being said to you but also the way the nurse stands next to you and it's through that supportive environment that a patient can feel safe and build trust.” (patient representatives, Greece) “The nurse, on the other hand, can do it, because he/she still has time to stay with the patient, he/she takes all the worst of the patient and therefore must try to motivate him/her, give him/her a sense of purpose even in keeping going when the situation is difficult, when he/she is sick.” (patient representatives, Italy) |

|

| Aspect 5: Being courageous |

“[Nurses] need to know how to justify intervention… courageous intervening in situations where there are ethically difficult issues… how to learn how to act in them” (nurses, Finland) “The ALS disease is quickly degenerative. People get a diagnosis, but sometimes within two months the stage has progressed so far that it is too late to make certain decisions. And that's why the word 'dare' is important. […] If you see that it's someone who's going through a longer process before they get to a more advanced stage, then you can take the time to talk about that, but when you're dealing with a patient who's at an advanced stage, then you shouldn't wait a month to talk about wills and the like.” (patient representatives, Belgium) |

|

| Aspect 6: Being open-minded, socially responsible, and culturally competent | “Meeting patient (encounter)- there is a lot to be learned about how to encounter individuals from different backgrounds and cultures … what attitudes are there towards diversity”. (nurses, Finland) | |

| Aspect 7: Being unbiased, non-discriminative, and inclusive |

“I believe that we should identify whom we have in front of us, and what they want from us, don't change the way we work by favouring someone, because of his/her socio-economic status” (nurses, Cyprus) “The first thoughts that pop into my mind are being respectful towards the patient and the human rights in general or even the ability to care for each individual equally…even the ones that sometimes get on their nurses’ nerves.” (patient representatives, Greece) |

3.3.1. Subtheme 1: knowledge

The first subtheme of moral competency comprised different aspects of knowledge that nurses must possess. Two different main aspects of knowledge were identified: professional knowledge and ethical knowledge. While these are described here as being distinct in some ways, they are not mutually exclusive. In practical terms, the different types of knowledge worked in harmony to help nurses provide care that was informed by clinical evidence, legislation, cultural context, and ethics. The different scenarios that participants talked about highlighted not just the range of care contexts, but also the complexity of the knowledge that was required.

3.3.1.1. Aspect 1: professional knowledge

Participants considered possession of professional knowledge to be a primary aspect of moral competence, because it informs nurses about what to do and how to practice appropriately in different clinical areas. Participants thought that nursing knowledge was a fundamental aspect of professional knowledge, because it is crucial for correctly identifying ethical issues, and it gives nurses an understanding of how to handle ethical challenges in clinical practice. In addition, the participants talked about nurses needing to possess knowledge of different health conditions and the ability to appropriately apply this knowledge.

Professional knowledge does not only encompass clinical knowledge, but also knowledge of current legislation and deontological rules. Knowledge of legal and deontological frameworks enables nurses to work legally within established boundaries, which were discernible or ‘visible’ to them because of their experience. Included in having knowledge of current legislation and deontological rules is mastery of human rights. Human rights’ knowledge allows nurses to advocate for patients in ethically challenging situations and gives them tools to inform patients about their rights. Nurses’ application of this aspect of knowledge helps patients to advocate for themselves too.

3.3.1.2. Aspect 2: ethical knowledge

While professional knowledge was identified by participants as being essential for informing nursing practice, another prominent aspect of knowledge is ethical knowledge. Participants said that moral competence included understanding foundational principles of ethics, such as respect for autonomy, and how it impacts care delivery. These fundamental ethical principles included knowing about ethical theories. Beyond simple awareness of ethical knowledge, participants said that moral competence included being able to act appropriately when these foundational principles are being overlooked in practice. This meant that the ethical knowledge had to be translated from abstract theoretical expressions into real-world living expressions that are applied where nurses work and to what they experience every day.

3.3.2. Subtheme 2: skills

The second subtheme or component of moral competence in nursing is skills. Our analysis identified two aspects of this subtheme: interpersonal skills and reflective skills. During the focus group discussions, both nurses and patient representatives talked about nursing as a skill-based profession. Central to this discussion was the nurses’ repeated use of the term ‘interpersonal skills’. Underpinning this notion is the understanding that nursing is a relational practice that requires mastery of certain skills. One of these skills is being able to communicate effectively. Nurses also said that honing reflective skills enabled them to deal with ethical issues better and that this skill was considered important for moral competency as well.

3.3.2.1. Aspect 1: interpersonal skills

Having excellent interpersonal skills were seen as being so important that achieving moral competence in nursing would be impossible without them. Participants spoke of how these skills developed through nurses’ cultivating feelings of trust and safety in patients, which promoted an environment for a caring relationship with the patient. At the core of this trustful and safe relationship with patients was the nurses’ communication skills. All participants stressed the importance of nurses’ ability to recognise and respond to both verbal and non-verbal cues from patients.

Although applying one's interpersonal skills within the nurse-patient relationship was important, some participants also stressed the importance of applying good interpersonal skills with team members as well. This was not limited to just members of the multidisciplinary team, but also included members of the support staff as they were also in close contact with patients and their families.

Our analysis also noted the importance of the ability of nurses to discuss and reflect with team members having different perspectives and discussing these perspectives in different contexts (e.g., academic vs. clinical practice). Having this skill encouraged diverse viewpoints to be expressed, not only from nurses but also from all those who work around the patient, moving the discussion towards a common solution appropriate for each patient. Honing this kind of skill allows nurses to continue to develop as a professional, contributing to their moral competence. Nurse participants also underlined the importance of being able to interact effectively with other dedicated care services, such as ethics committees. A nurse gave concrete examples how interpersonal skills can be trained.

“Yes, role playing or even discussion of cases, maybe in small groups, each dealing with a clinical case, which is centred on an ethical dilemma so that each one can bring in his/her group the knowledge he/she has learned during the course. … That each of us sees things from a different perspective.” (Nurse, Italy)

Participants said that nurses’ ability to relate and communicate also applied to their communication with the patient's family. Although healthcare environments can be emotionally charged places, making communication with families particularly challenging, patient representatives considered this aspect of moral competence to be a vital skill. Being an empathetic communicator is especially vital when nurses must communicate ‘bad news’ to families. Patient representatives were acutely aware of this issue and spoke about the need for nurses to be sensitive to the individual needs of families—like they are with the patients themselves.

3.3.2.2. Aspect 2: reflective skills

The nursing participants mainly discussed the notion that competent nurses must possess reflective skills allowing nurses to work through daily ethical challenges and demanding situations. Possessing reflective skills enabled nurses to quickly recognise ethical issues and then use these skills to identify the range of possible solutions. Having this skill basically meant that nurses could consider not just their own perspective but also those of other stakeholders.

Finally, participants underlined the importance of morally competent nurses’ ability to prioritise tasks effectively and address care needs in a timely manner. This element of reflective skills allowed nurses to optimise nursing care and organise their time according to the urgency and complexity of a given nursing intervention. It also supports the nurses in considering context in their decisions. Adding context to decision-making was mentioned as helping nurses to take the most appropriate action that would minimise any distress or harm that might be caused, given the available alternatives in that context.

3.3.3. Subtheme 3: attitudes

The third and final subtheme or component of moral competency in nursing that emerged from our thematic analyses was nurses’ attitudes. Many different aspects of attitudes of the morally competent nurse were identified. For example, attitudes related to being curious in learning situations, being patient, being able to accept that there are limits to one's own abilities, being responsible for making choices, being tolerant of others’ values and choices, being discrete, and, finally, attitudes related to inspiring confidence in others. These specific attitudes that were discussed only by participants in some countries’ focus groups are not considered further here. However, there are some attitudes that were reported by participants in all countries and all focus groups. These commonly discussed attitudes are presented below.

3.3.3.1. Aspect 1: being empathic

Participants in the nurses’ and patient representatives focus groups discussed the importance for a morally competent nurse to be able to place themselves in another person's situation, being open towards others to better understand the reasons for some of the patient's unique needs, concerns, and choices. Empathy here is understood to mean understanding of another's situation, perspectives, feelings, and motives.

3.3.3.2. Aspect 2: being respectful

Another attitude identified was being respectful towards patients’ life and care choices. While important across all care contexts, nurses being respectful was essential for moral competence, especially when the patient was more vulnerable due to their age or disability.

Additionally, patient representatives mentioned that the morally competent nurse can protect a vulnerable person's dignity in a respectful way. Being respectful also meant that the morally competent nurse is physically present with both the patient and the patient's relatives, despite their workload and workplace-related frustrations. Being respectful meant that the patients they are caring for, as well as the patients’ relatives, don't feel like a burden.

3.3.3.3. Aspect 3: being honest

Another aspect is the attitude of nurses to be honest with patients under their care, highlighted mainly by patient representatives. Furthermore, participants mentioned not just being honest in terms of information content delivered to patients, but also being honest in terms of how the nurses delivered information, specifically the clarity and tone of the message.

3.3.3.4. Aspect 4: being motivating and supportive

Patient representatives especially noted that morally competent nurses should have an attitude that is motivating and supportive, helping the patient to persist in participating in the care process. Nurses having this attitude helps the patient have a positive care experience, characterised by feelings of trust and safety.

3.3.3.5. Aspect 5: being courageous

Both nurses and patient representatives suggested that acting in a morally courageous way is an important attitude for a nurse to possess in order to be morally competent. Participants said this was essential in situations that required the nurse to be the patient's advocate.

3.3.3.6. Aspect 6: being open-minded, socially responsible, and culturally competent

Participants described the importance of having an attitude that was expressed by open-mindedness and social responsibility. They reported the aim of such an attitude cultivated responsible citizenship. This open-mindedness was said to be closely linked to the characteristic of being culturally competent. Thus, the morally competent nurse is aware of cultural transformations over time, which is essential in providing transcultural care. In this context, the nurse acknowledges cultural beliefs and practices in all dimensions of the patient's healthcare. Recognizing the particulars of different cultures helps nurses to work effectively with people who may have different values from their own. For example, some cultures might have beliefs that are inconsistent with certain health practices. The morally competent nurse recognises this and will deal with it in a professional and cultural-sensitive way. One of the nurses said:

“We have many foreign nationals who come to our country and, unfortunately, become ill, requiring treatment in our hospitals. However, what is considered morally acceptable in our culture may be viewed as immoral in theirs.” (Nurse, Cyprus)

3.3.3.7. Aspect 7: being unbiased, non-discriminative, and inclusive

According to all participants, morally competent nurses are unbiased and act impartially. This meant that they care for all patients without prejudice, regardless of the patient's socio-economic status, age, or any other social or personal dimension. The nurses ensure that every person is given fair and equal treatment. They do so by addressing physical, psychological, social, and existential needs that are consistent with best care practices. At the same time, they protect the rights of their patients and do not accept uninvited or inappropriate interference from third parties (e.g. supervisors’ interventions) that force them to act unethically.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the main results

In this study, we sought to explore nurses’ and patient representatives’ perspectives on which characteristics define the morally competent nurse through focus group discussions. Data collected from six European countries indicate that both nurses and patient representatives see morally competent nurses as person-centred and possessing the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to build strong relationships with patients, their families, and colleagues. To further explore the meaning of moral competence of nurses in nursing care and identify its key components, it is essential to critically examine the nature of nursing care and the types of knowledge that are most significant within the nursing discipline. Accordingly, we situate the findings of our empirical study in conversation with key works from the normative nursing ethics literature.

4.1.1. Nursing as a relational moral practice

The participants emphasise that nursing should be viewed as a moral practice, one that is fundamentally characterised by a caring relationship; it integrates both professional and ethical knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Similarly, in Gastmans et al. (1998) this same combination of qualities forms the essence of caring behaviour in ethical nursing practices. According to our participants, the caring relationship involves cultivating virtuous attitudes such as empathy, respect, honesty, courage, openness, which are essential for providing person-centred care to patients. The caring relationship also requires the mastery of specialised knowledge and skills, which enable nurses to address each patient's unique needs. A central thread that pulls these characteristics together is the nurses’ use of their interpersonal skills, which enables them to adapt accordingly to changing contexts. Thus, by applying their interpersonal skills, morally competent nurses will work in different ways to meet the needs of patients and families and will ensure that their voices are heard.

Recognising the pivotal role of person-centredness in nursing practice involves understanding nursing care as a reciprocal interpersonal process that entails interaction, fostering of close relationships, and transactions between the nurse and the patient (Carper, 1978; Gastmans et al., 1998). This underscores the need to establish genuine human connections between nurses, patients, and patients' relatives (Pearson et al., 2024). Our study confirms previous studies’ findings that good nursing care hinges on the nurse-patient relationship that provides the specific context in which nursing can flourish. It serves as the environment in which practical care is delivered and as the primary wellspring of knowledge for developing nursing theory.

Similarly, the present study elicits that nurses and patient representatives alike believe that morally competent nurses are attuned to the diverse contexts in which they practice, while also recognising the importance of advocating for their patients' dignity and human rights. The attributes highlighted by the participants in our study underscore the complex nature of moral competence in nursing care. Our findings indicated that relevant stakeholders agree that morally competent nurses play a crucial role in promoting a person-centred healthcare environment. According to our participants, they should do so by prioritising patients' needs, values, and dignity, and by fostering collaboration and respect within interdisciplinary teams. According to Gastmans et al. (1998), nursing care becomes a tangible embodiment of ethical practices, as nurses develop personal bonds with patients and as they develop respect for their patients’ uniqueness.

Recent interview studies with nurses show that positive interpersonal relationships among colleagues benefit ethical communication. Additionally, support and mutual respect contribute to moral behaviour (Choe et al., 2022). Findings from these studies emphasise the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration in establishing a person-centred healthcare environment. Considering the importance of moral competence and the various factors that contribute to it, further investigation is necessary to explore how nurses can effectively collaborate with professionals from other disciplines, such as social work, psychology, and medicine, to further bolster moral competence and improve patient care outcomes (Choe et al., 2022; Wiisak et al., 2024).

4.1.2. Ethical knowing in nursing

Our focus groups participants elicited that moral competence also requires a deep understanding of the importance of specific types of knowledge in nursing care. Based on our results, as well as on results from prior research—specifically results coming out of Carper's seminal work, “Fundamental Patterns of Knowing in Nursing” (Carper, 1978)—we believe that nursing care involves recognising and addressing individual patient needs and expressions, while, at the same time acknowledging the patients as continuously evolving individuals. Viewing nursing care as a comprehensive, interconnected experience within the context of human life processes reveals profound insights beyond mere practical routines. As a result, this enhances moral competence in nursing care. We believe that developing awareness of the ethical sensitivity of every nursing action and addressing ethical dilemmas involves prioritising the patients’ best interests and making decisions tailored to their specific circumstances. The care provided by the nurse to the patient should not be seen solely as an expert activity, performed according to strict rules or norms. On the contrary, nursing care should be viewed from the perspective of the caring relationship. Establishing a caring relationship requires one to develop a compassionate attitude, which becomes a character trait moulded, in part, by being cognisant of one's unique situation and context (Garcia-Urib and Pinto-Bustamante, 2024). Our participants’ perspectives on what makes a morally competent nurse align perfectly with this relational approach. They emphasize how, although technical skills and professional knowledge are essential, nursing care is not solely about these skills. Nursing care focuses on establishing meaningful relationships and delivering high-quality care to patients who are embedded in unique circumstances (Gastmans et al., 1998). Therefore, caring involves not only scientific knowledge, but also a sensitive awareness of the values and significance of life, health, suffering, and human vulnerability (Vanlaere and Burggraeve, 2024). This ethical knowledge extends beyond the fundamentals of codes of practice in the field.

Considering various patterns of knowing in nursing, as proposed by Carper (1978), it is imperative to acknowledge that nursing should not only be grounded in empirical knowledge. Rather, it also should encompass ethical, aesthetic, and personal understanding. Person-centred care requires carers to pay attention to all systems of information and their interactions, including ethical knowledge and moral competence. However, ethical knowledge and moral competence do not exist in a vacuum. Rather, they are responsive to all patterns that work together in the provision of care.

This brings us to a final consideration regarding the meaning of moral competence in nursing. It appears that our study participants assumed moral competence should be understood primarily within an ethics of individual relationships, particularly between the nurse, the patient, and the patient's family. However, the nurse-patient relationship cannot be viewed in isolation. On the contrary, it exists within the broader context of the healthcare system, which is shaped by a hierarchical team of caregivers working within healthcare institutions. These organizations may not always function morally or may interpret moral competence differently (Wiisak et al., 2024). Furthermore, nurses’ ability to express moral competence is influenced by factors such as the power dynamics between physicians and nurses, the working relationships within the care team, and the broader institutional environment. These contextual factors might create significant tension, making it more challenging for nurses to consistently uphold morally sound practices. Moral competence in nursing develops in an environment marked by power imbalances, inefficiency, work pressure, varying levels of competence, and limited resources. These factors play a critical role in shaping how moral competence can be expressed and cultivated by individual nurses (Koskenvuori et al., 2019; Ammari and Gantare, 2024; Yu et al., 2024). Therefore, more research is needed for the further development of a contextualized approach to moral competence in nursing, encompassing the larger interprofessional, institutional, and societal contexts in which nursing practices unfold.

4.2. Methodological discussion

One strength of our study is that it conducted focus groups in six different countries. To ensure the rigour of this study, the recruitment and data collection processes were done in each country according to a pre-established protocol.

Another strength of this study is participant heterogeneity. We involved two different groups of participants (nurses and patient representatives) from the six different participating countries. We decided to include these six countries because of their varied locations in Europe (north, south, and west); their diverse cultures and values; their different healthcare systems; and because each country has different nursing educational systems (Papastavrou et al., 2024). However, we should emphasize that the results of our study are influenced by the participants’ perspectives on nursing and healthcare as they are organised in their country. Since no structured consensus methodology is available to guide international focus group studies, the process we followed may have led to some biases. We have attempted to minimise these biases using some of the processes already mentioned (e.g., pre-established protocol for recruitment and data collection).

Although focus groups can provide an environment for revelatory interactions among participants, it is also possible that certain participants may tend to hold back from expressing their opinions. To facilitate discussions in our focus groups, a moderator and a facilitator were present to ensure that all participants were included in the discussions.

The collaboration between researchers from six countries requires flexibility and openness so that all researchers can meaningfully discuss all aspects of the research process. One of the challenges within this study was the language diversity among the different participating countries. To address this issue, each focus group was conducted in the local language. This meant that the concepts and quotes extracted from the focus group discussions had to be translated into English at a later time, so that they could be analysed on an international level. As a result, nuances in the original-language transcript may have been lost. On a more conceptual level, the heterogeneity across the six countries and healthcare systems may have influenced the definitions of ethics, moral competence, and moral behaviour, both implicitly and explicitly, as used by the interviewees and the researchers. Finally, it is important to note that women were overrepresented in both types of focus groups.

4.3. Implications for education and research

This study provides a framework (Fig. 1) for supporting nurses’ ethical competence in nursing practice through education. This framework was derived from a consensus of viewpoints from both nurses and patient representatives. Nursing educators would find our present findings to be useful for identifying how moral competence in nursing can be understood and how nurses can be better prepared to be morally competent. Also, the framework provides a structure for the development of educational interventions. The members of the PROMOCON consortium will use the results of this study to develop a MOOC and a best practice guide on nursing ethics that can be used for basic and continuing education in nursing.

For research, the framework can be useful for developing measures for and assessments of moral competence in nurses.

5. Conclusions

This international study provides a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of the morally competent nurse from the perspectives of both European nurses and patient representatives. The main characteristic of a morally competent nurse is person-centredness, which is reflected on intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. Additionally, the morally competent nurse has the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to cultivate relationships with patients, their families, and nursing colleagues.

The findings of this study may be useful to those involved in nursing education for identifying how moral competence in nursing can be supported and how nurses can be better prepared to deal with ethically sensitive situations. Also, the results provide a framework that can support the development of educational interventions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chris Gastmans: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Evelyne Mertens: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Alvisa Palese: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Brian Keogh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Francesca Apolloni: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Johanna Wiisak: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Catherine Mc Cabe: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Maria Dimitriadou: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Alessandro Galazzi: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Michael Igoumenidis: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Nikos Stefanopoulos: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Paraskevi Charitou: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Evridiki Papastavrou: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Riitta Suhonen: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Stefania Chiappinotto: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Chris Gastmans, Alvisa Palese, Catherine McCabe, Michael Igoumenidis, Evridiki Papastavrou, Riitta Suhonen report financial support was provided by European Commission. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding was provided by the Erasmus + programme of the European Union (agreement no. 2022–1-IT02-KA220-HED-000087544). The European Commission's support to produce this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors. Thus, the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use of the information contained therein.

Data availability

The raw data from this study will not be shared to ensure the protection of participants' privacy and confidentiality. Additionally, the data contains sensitive information that could potentially identify individuals, making it ethically and legally imperative to withhold the data from public access.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in the focus groups for sharing their experiences and perspectives as well as Alice Cavolo for her comments on earlier versions of the article.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnsa.2025.100296.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ammari N., Gantare A. Ethical climate and turnover intention among nurses: a scoping review. Nurs. Ethics. 2024 doi: 10.1177/09697330241296875. Nov 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]